In his discussion earlier today, Matthias Wivel argues that Chester Brown’s Paying For It includes an implied sacred component. Pointing to the use of distant views and the wormhole effect Brown uses in many panels, especially those depicting sex, Matthias argues that Brown presents a God’s-eye view of his own life, universalizing and consecrating his own experiences.

many scenes are viewed from above, from a kind of “God’s eye-perspective.” The peepshow aesthetic of the tiny two-by-three paneling seems to be for the benefit of an omniscient viewer, who at times loses interest and lets the eye wander, decentering the compositions. Chester walks, talks, and fucks under the scrutiny of a dispassionate oculus, darkening around the edges. It is almost as if he is inviting a higher judgment to balance out his own.

Sex scenes are privileged by even greater distance. They are uniformly denoted by a throbbing glow in the dark, blocking out the surroundings (this is worked to hilarious effect in chapter 2—the sequence where Chester keeps stopping, with the banal details of the surrounding room appearing each time). A necessary way of avoiding the interference that overly graphic renditions would create, this approach lends universalism to these scenes, threading them through the narrative as its central, ‘sacred’ constituent.

Brown’s cartooning has struck me as invoking this kind of higher order since at least, and unsurprisingly, his 1990s Gospel adaptations, which routinely employed a similarly elevated perspective, pared-down panel compositions, and suggestive framing to great effect.

It’s an interesting argument…but one that I’m afraid I don’t find especially convincing. I certainly agree that Brown is using a distancing mechanism. But I don’t think that distancing mechanism needs to imply a God or a sacralization. On the contrary, it seems to me that the eye you see through when you look at Brown having sex is not the eye of God, but the eye of porn. It does not provide a deeper insight, or a spiritual glow. On the contrary, the distancing turns Brown and his partners into rutting meat dolls, robbed of inner life or soul (you can’t, notably, see their eyes.) The distancing is not a means of handing control over to a larger power; it’s a way of enforcing control; of nailing human emotions and interactions down like butterflies in a sample case. It’s the expression not of spiritual insight, but of sadistic gaze.

I think this has some interesting implications for Matthias’ other arguments. He suggests that some critics of Paying For It (especially me) have focused on the polemic and failed to respond to the formal successes of Brown’s work. Those formal successes are (in a nice reversal) precisely the spiritual successes; they are the ineffable which give life to the comic. Or, as Matthias says, “[Brown’s] power to imbue any scene with an ineffable sense of meaning is one of his great gifts as a cartoonist, a gift few critics have attempted to critique or explicate, and which Spurgeon addressed sensitively in his review.”

What Matthias doesn’t seem to consider is the possibility that critics haven’t attempted to explicate or critique this gift in reference to Paying for It because the gift isn’t there. Brown’s grids, his simplified figures, the often mechanical stillness of his figures, the cadaverous death’s head of his self-portrait…it’s not, to me, suggestive, or spiritual, or ineffable. It’s ugly, routinized, and intentionally flat, almost desperate in its eschewal of beauty or resonance.

I do agree with what I take to be Matthias’s position that the blankness of the art has a thematic meaning. The art’s frozen distance undercuts Brown’s polemic, calling into question his claim that prostituted sex is joyful or spiritual.

The problem for me is that I don’t have much desire to see ugly, boring truths depicted in ugly, boring art. I’m not that interested in Chester Brown per se, so watching him work out his fairly transparent control issues by systematically draining his art of life and joy doesn’t appeal to me that much. Matthias sees this as a lack of sensitivity to the formal achievement…but surely it could also be simply a different evaluation of that achievement. Matthias sees God in the interstices of Brown’s routinized panels, and declares that those who don’t see Him are insufficiently attuned to the spiritual. Perhaps. But still, I look at Paying for It and what I see is the machine clanking and pistoning, grinding out hollow banality because hollow banality is what libertarians and autobio comics alike use to keep the ineffable at bay.

But “the eye of porn” is designed to get the viewer off. Surely that’s not the effect of this POV. It’s hardly titillating, at least not from a traditional porn viewpoint.

Not that I’ve read the book…it’s a family tradition.

There’s a fair bit of porn theory that argues that the purpose of porn is not actually to get people off. Linda Williams argues that it’s much more about gaze and knowledge than it is about sexual pleasure per se, for example.

I don’t want to disagree with Linda Williams…but the shots here from Paying for It don’t resemble much porn that I’ve seen…not that I’m any sort of expert. Getting off seems to at least be part of the equation in much of it.

I agree with eric b, the shot don’t resemble any porn that excites. By the way, the discussion of porn reminds me of this TCJ article I read.

http://www.tcj.com/drawing-sex-and-paying-for-it/

It’s similar to porn in that it’s clinical and distanced, and about bodies rather than people. The way it’s a mechanical series of positions without narrative content and framed from an outside perspective rather than from the perspective of either of the participants; it’s all stereotypically sadistic and pornographic.

HI Noah,

As with so much of what you write, I find myself in complete agreement, both in your assessment of “Paying for It” and your criticism of Brown’s (anti-)aesthetic.

The final nail in this coffin — a coffin that holds, I assume, a very dead piece of meat — comes in Chapter 7. In this section, we get (all at once) the only close-up of the entire comic, the most realistic representation of the human body, and the most drawn out temporal sequence. It is an examination of Brown’s penis.

And an examination — or, as he calls it, an “inspection” — is the proper word. The exam is cold and calculating and complete (left, right, up, down). If it is a consideration of the penis, it is not as an amatory organ or area of arousal, but as a possible site of disease. Indeed, it hardly seems to grow erect in the woman’s hand.

This is a vital (excuse the word) part of the story and of Brown’s use of his art. The body, for Brown, must be a manipulable thing — because that is the only way you can adequately buy and sell it, I suppose.

Emotions can be faked (he worries about that by the end of the page). Pleasure or pain can be faked. Love and hate can be faked. But the blunt presence of the body — the thingness of the flesh — cannot be denied. (No wonder he draws himself as a skeleton: a counterpart to the fleshiness of the women, all boobs and butts and hair and cellulite.) The penis is hard or it isn’t, is penetrating or not, is suppurating or not.

To kill romance, you have to first kill those things that make romance more than a body. You have to formalize sex, make it a matter of form, understood entirely from the outside. To paraphrase Stanley Fish, Brown wants love to have a formal existence. He will not get what he wants. So he’ll take whatever’s left behind — or at hand.

This — in more ways than one — is his money shot.

Hey Peter. Great to see you here again. That’s a great discussion…and I think points to the way that the absence of faces ends up being a bit too convenient….

I liked the coldness of the book. Thematically. Imagine what it would be like if Crumb drew it. It would be a shitfest.

The precision…anal retentiveness of the storytelling and clinical depictions allow this comic to feel more like an almost objective examination of Brown’s experiences. Of course it’s NOT objective because it’s Brown himself making the comic, but that’s how it reads.

If Crumb had drawn it, it would likely have been a masterpiece…but this is so far from Crumb it’s too improbable.

Alex: surely you meant to write “masturbation-piece.”

Heh! Both.

As Woody Allen says, “What’s wrong with masturbation? At least it’s sex with someone you love.”

So go ahead, peeps– be your own best friend!

(And, Chester Brown, save money!)

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/Thinking2-1.jpg

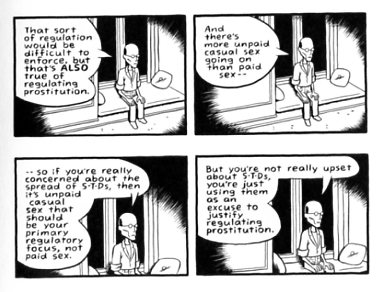

I took that distancing to be not the eye of god or the eye of porn but the eye of reason. Brown is incredibly wrapped up in proving to himself that he believes the things he believes because of rationality and logic. In his market-driven view of the world, the women don’t need faces, because they’re just products and services. By pulling back to a worm’s eye view, Brown reinforces that his reasoning is as removed and calm and correct as possible.

Jason, I think that works quite well. I think reason and porn are pretty closely connected in Brown’s world. Sadism is connected to both; it’s routinized distance as erotics. Brown finds prostitution exciting/fulfilling precisely because it’s “reasonable”. The distancing effect therefore reinforces the calm remove and validates the experience.

There’s every reason to think from Brown’s discussion that he finds, or is presenting, the anonymous grinding of meat puppets as erotic. Just because many other people find it repulsive doesn’t mean that that was Brown’s intention.

——————————

Jason Michelitch says:

…Brown is incredibly wrapped up in proving to himself that he believes the things he believes because of rationality and logic.

——————————-

Indeed so! Speaking of another Canadian comics creator in the same boat, I wonder what Dave Sim thinks of “Paying For It”?

Couldn’t find anything online, only these tangential bits:

——————————-

Brown began to question traditional male-female relations after he had read Cerebus the Aardvark #186, which contained an essay attacking the modern state of such relations…

Brown made his visiting of prostitutes known to his friends and relatives (except for his stepmother) shortly after his first visit, and it had been made public long before the appearance of Paying for It, as in his interview with Dave Sim in Cerebus #295-297…

Brown’s aversion to relationships with women drew tentative comparisons to friend and fellow cartoonist Dave Sim, known for his controversial views on women. Brown responded to this by saying, “…I don’t think women are intellectually inferior to men. But I like being alone.” Brown also publicly debated the subject with Sim in the Getting Riel interview, while acknowledging that “Cerebus #186 [the issue in which Sim first laid out his controversial views] did push me in the direction of questioning the whole romantic relationship thing”…

——————————–

…Who better to get love advice from than Dave Sim?

———————————

Brown…also intended to include more details of the prostitutes he visited, such as their interests and the conversations they had, but was afraid too much detail could identify them — he chose to respect their anonymity; this includes “Denise”, the prostitute with whom he ended up having a long-term, monogamous relationship, and who refused to have more of herself included in the book..

Conversations and debates with Dave Sim were also dropped, as their friendship fell through over Brown’s refusal to sign an online petition asserting Sim was not a misogynist, and Brown felt awkward asking Sim for permission to include those scenes.

——————————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paying_for_It