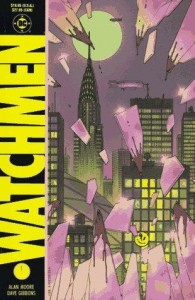

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen is certainly no stranger to “best of” lists. In 2008, Entertainment Weekly looked across the entire landscape of book publishing—fiction and non-fiction, prose efforts and comics works—and put together a ranked list of the “100 Best Reads from 1983 to 2008.” (Click here.) Watchmen was listed at #13, which included it among the top ten works of fiction of the period. And a few years earlier, in 2005, Time magazine included Watchmen in its list of the 100 best English-language novels between 1923 and 2005. (Click here.) Time is an establishment publication, and it is certainly not prone to any radical pronouncement. The magazine put Watchmen in the company of such classics as The Great Gatsby, To the Lighthouse, and The Sound and the Fury. The book’s more contemporary peers included Beloved, American Pastoral, and Never Let Me Go. No other comics work was given this distinction.

Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons’ Watchmen is certainly no stranger to “best of” lists. In 2008, Entertainment Weekly looked across the entire landscape of book publishing—fiction and non-fiction, prose efforts and comics works—and put together a ranked list of the “100 Best Reads from 1983 to 2008.” (Click here.) Watchmen was listed at #13, which included it among the top ten works of fiction of the period. And a few years earlier, in 2005, Time magazine included Watchmen in its list of the 100 best English-language novels between 1923 and 2005. (Click here.) Time is an establishment publication, and it is certainly not prone to any radical pronouncement. The magazine put Watchmen in the company of such classics as The Great Gatsby, To the Lighthouse, and The Sound and the Fury. The book’s more contemporary peers included Beloved, American Pastoral, and Never Let Me Go. No other comics work was given this distinction.

When one reads Watchmen, whatever skepticism one has about such acclaim quickly falls away. It is a superb work that triumphs on multiple levels. Watchmen is simultaneously a first-rate adventure story, an incisive analysis of the superhero genre, and a brilliant meditation on how one’s sense of reality is defined by one’s perspective—knowledge and ignorance, hopes and fears, predispositions and agendas.

The book’s starting point is a mystery plot. The Comedian, a former costumed hero and now a covert government operative, is brutally murdered. It gradually becomes clear his murder is part of a larger conspiracy. Dr. Manhattan, the only one of the heroes with superpowers—and he is nearly omnipotent—is driven away from society by an elaborate smear. Rorschach, the last of the heroes to operate without government sanction, is framed for murder, captured, and imprisoned. Ozymandias, who retired from adventuring years earlier, foils a gunman’s attempt on his life. Someone is out to eliminate the heroes, but who, and why?

The answer turns out to be horribly ironic, with the reasons a black joke on the puny, naively idealistic desire to make a better world by putting on a costume and beating up criminals. The conspiracy to eliminate the costumed heroes is revealed as a tangent in a greater plot that changes the world. Along the way, Moore and Gibbons treat the reader to one terrific suspense setpiece after another. And in marked contrast to Zack Snyder, the director of the horrid film adaptation, they understand that violence is made all the more effective by restraint.

One of the most common observations about Watchmen is that it is both a superhero adventure story and a critique of the genre. In the appreciation of the book he sent with his top-ten list, Francis DiMenno identifies this with critic Harold Bloom’s theory of the “anxiety of influence.” In DiMenno’s view, Alan Moore, the book’s scriptwriter and acknowledged mastermind, has such a relationship with the superhero genre. One can see his point, but I’m more inclined to identify Watchmen’s anxiety of influence with Harvey Kurtzman’s “Superduperman” and other superhero parodies in MAD. The theory argues that a younger artist feels belated relative to older ones whose work is admired. The only way to compete with the older work—and assert one’s own artistic identity—is to beat the earlier artist at his or her own game, which is accomplished by changing the rules. In works like “Superduperman,” Harvey Kurtzman exposed the fallacies of the genre with derision and exaggeration. In contrast, Moore, who acknowledges a large debt to Kurtzman, examines his own superhero characters with the acute eye of a first-rate prose novelist. He doesn’t mock them; he plays things entirely straight, and he presents the fanciful characters in as ruthlessly realistic a manner as possible. He reveals the grotesquely maladjusted attitudes that motivate the various superheroes, turning them into figures of pathos and horror. Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, and the others are among the most memorable characters in contemporary fiction.

One of the most common observations about Watchmen is that it is both a superhero adventure story and a critique of the genre. In the appreciation of the book he sent with his top-ten list, Francis DiMenno identifies this with critic Harold Bloom’s theory of the “anxiety of influence.” In DiMenno’s view, Alan Moore, the book’s scriptwriter and acknowledged mastermind, has such a relationship with the superhero genre. One can see his point, but I’m more inclined to identify Watchmen’s anxiety of influence with Harvey Kurtzman’s “Superduperman” and other superhero parodies in MAD. The theory argues that a younger artist feels belated relative to older ones whose work is admired. The only way to compete with the older work—and assert one’s own artistic identity—is to beat the earlier artist at his or her own game, which is accomplished by changing the rules. In works like “Superduperman,” Harvey Kurtzman exposed the fallacies of the genre with derision and exaggeration. In contrast, Moore, who acknowledges a large debt to Kurtzman, examines his own superhero characters with the acute eye of a first-rate prose novelist. He doesn’t mock them; he plays things entirely straight, and he presents the fanciful characters in as ruthlessly realistic a manner as possible. He reveals the grotesquely maladjusted attitudes that motivate the various superheroes, turning them into figures of pathos and horror. Rorschach, Dr. Manhattan, and the others are among the most memorable characters in contemporary fiction.

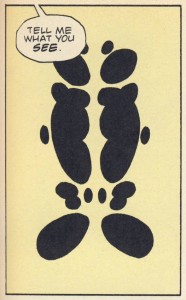

Watchmen is an extraordinarily compelling read, but what makes it an extraordinarily compelling reread is its meditation on perspective and how it shapes one’s understanding. On its most profound level, the book is about interpretation and the act of reading itself. The work’s defining metaphor is the Rorschach blot—a psychiatric tool for teasing out a person’s attitudes and preoccupations. One is asked to look at a blob of ink and elaborate the associations and thoughts one projects onto it. One sees permutations of this throughout the book, such as when Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias, and a third hero, Nite Owl, attend the Comedian’s funeral. They think back on him during the service, and it’s clear none had any significant relationship with him; they only see him as a metonymy for their own anxieties. Moore and Gibbons also dramatize the most extreme perspectives; in one chapter we are shown experience through the eyes of a psychopath, and in other we see things through the eyes of eternity, and understand what it can mean to be aware of all times at once. The book almost always presents knowledge as incomplete. And when it is complete, it is skewed by other factors, so people fail to reach the correct conclusions. In one of the book’s subplots, the main female character knows everything necessary to recognize a certain man is her real father, but her dysfunctional relationship with her mother so distorts her view that she can’t see it. And misunderstandings not only affect one’s personal life, they direct the tide of history. At the end of the book, the world has changed because everyone misinterprets a catastrophe. Will they accept the truth once they are told it? The book ends on that question, and one is inclined to answer no.

Watchmen is an extraordinarily compelling read, but what makes it an extraordinarily compelling reread is its meditation on perspective and how it shapes one’s understanding. On its most profound level, the book is about interpretation and the act of reading itself. The work’s defining metaphor is the Rorschach blot—a psychiatric tool for teasing out a person’s attitudes and preoccupations. One is asked to look at a blob of ink and elaborate the associations and thoughts one projects onto it. One sees permutations of this throughout the book, such as when Dr. Manhattan, Ozymandias, and a third hero, Nite Owl, attend the Comedian’s funeral. They think back on him during the service, and it’s clear none had any significant relationship with him; they only see him as a metonymy for their own anxieties. Moore and Gibbons also dramatize the most extreme perspectives; in one chapter we are shown experience through the eyes of a psychopath, and in other we see things through the eyes of eternity, and understand what it can mean to be aware of all times at once. The book almost always presents knowledge as incomplete. And when it is complete, it is skewed by other factors, so people fail to reach the correct conclusions. In one of the book’s subplots, the main female character knows everything necessary to recognize a certain man is her real father, but her dysfunctional relationship with her mother so distorts her view that she can’t see it. And misunderstandings not only affect one’s personal life, they direct the tide of history. At the end of the book, the world has changed because everyone misinterprets a catastrophe. Will they accept the truth once they are told it? The book ends on that question, and one is inclined to answer no.

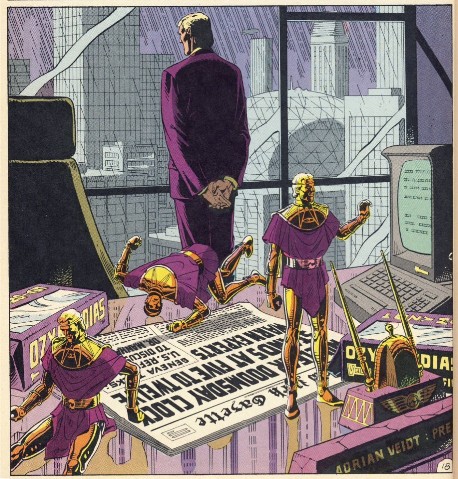

Moore and Gibbons extend their treatment of interpretation and misinterpretation to the reader’s experience of the book. If one has read Watchmen before, go back and reread the first chapter. Details that seemed extraneous the first time around jump out at one. Others, such as the recurring image of the spattered smiley face, recede into the background. Dialogues take on a different meaning, such as the conversation between the two detectives in the opening scene. Is one sincere when he says a certain crime was probably random and not worth much investigation? Or consider this panel:

How was this image interpreted—i.e. what meaning was projected onto it—the first time around? Was the emotional resonance from an earlier scene with the Nite Owl character brought over to it? Did one see it as a pensive moment of doubt on Ozymandias’ part about how he has spent his life? Were the dolls in the foreground seen as a trope for this doubt? And how is it interpreted on the second reading, with knowledge of the entire book? Does one now see Ozymandias contemplating an unexpected problem, with the toys a trope for his distraction? This panel, like all of them, is a Rorschach blot for the reader; one sees what one projects onto it. The differing interpretations also bring to mind a quote Alan Moore was fond of in a later work, “Everything must be considered with its context, words, or facts.”

Illustrator Dave Gibbons does a magnificent job of realizing his collaborator’s vision. Moore may be the mind behind Watchmen, but Gibbons is its extraordinarily deft hands. He was a seasoned adventure cartoonist when he began the project, and one sees his assurance in every panel. He handles the quiet scenes as effectively as the violent ones. There’s also an understated, almost laconic quality to his dramatization of the characters. He shows the reader what is happening; one is never told what to think about it. And the remarkable literalness of his style—clear compositions, fully realized deep-space perspectives, copious detail—is perfect for a work that at its core is about the unreliability of perception. Gibbons shows the reader everything, and it remains ambiguous anyway.

I could go on and on about the book. It does what the most impressive ones do; it makes you want to talk about its achievements forever. That’s why it deserves to be considered one of the finest novels of our era. Not to mention one of the best comics.

Robert Stanley Martin is the organizer and editor of the International Best Comics Poll. He writes for his own website, Pol Culture, and is a contributing writer to The Hooded Utilitarian. He has previously written on comics for the Detroit Metro Times and The Comics Journal.

NOTES

Watchmen, by Alan Moore & Dave Gibbons, received 31 votes.

The poll participants who included it in their top ten are: J.T. Barbarese, Piet Beerends, Eric Berlatsky, Noah Berlatsky, Alex Boney, Scott Chantler, Tom Crippen, Marco D’Angelo, Francis DiMenno, Anja Flower, Jason Green, Patrick Grzanka, Paul Gulacy, Alex Hoffman, Mike Hunter, John MacLeod, Scott Marshall, Robert Stanley Martin, Todd Munson, Jim Ottaviani, Marco Pellitteri, Michael Pemberton, Charles Reece, Giorgio Salati, M. Sauter, Matthew J. Smith, Nick Sousanis, Joshua Ray Stephens, Ty Templeton, Matt Thorn, and Qiana J. Whitted.

Watchmen was originally published as a 12-issue serial in comic-book pamphlet form in 1986 and 1987. The serial was collected and published as a graphic novel in 1987, and has been a mainstay of book retailers ever since. It should also be available at most public libraries.

–Robert Stanley Martin

A finely illuminating write-up! Indeed, “Watchmen” is deserving of the praise it’s received…

——————————-

Time…magazine put Watchmen in the company of such classics as The Great Gatsby, To the Lighthouse, and The Sound and the Fury…

———————————-

…And Domingos goes: http://tinyurl.com/3dlwquy

And what richly realized characters populate the intricately detailed world Moore/Gibbons created. There are moments such as Laurie’s visiting her mother at the nursing home, and to her kvetching impatiently saying, “Mom, being lazy isn’t a terminal condition.” (Quoted from memory, as is the rest here.)

There’s the thoroughly decent psychiatrist, who infuriates his wife when having dinner with some friends, “spoils the mood” by telling the lubricious jackass who asked for sexy crime details about the grotesque ugliness of what drove Rorschach ’round the bend; and, when he moves to stop the fighting lesbian couple before “the balloon goes up,” is given a “this is the last straw” ultimatum against getting involved by the Missus, which he ignores, because helping people is what he does…

The scene when the news vendor and his black-kid namesake, as New York is about to be annihilated, when they move towards each other, his arms protectively wrapping around him, as they dissolve into whiteness… (Which moved me to tears.)

Writing of that scene reminding (am always finding new “things” in “Watchmen”) of how the comic-book writer, having discovered the time bomb about to go off in the ship where they’re leaving the island, tells his lover to just hold him…

Those put off by the costumes and genre workings will miss these and countless other moments and details, which add to the richness of the work.

When Watchman first came out I was excited to read it, but when I did I was disgusted by a plot line in which a raped woman falls for her attacker.For women readers it was an affirmation that this venue remained closed to females. Moore’s intial offensiveness further opened the way for the movie to make this a central theme of its narrative i.e. her forgiveness of her rapist was the jusitifcation for the salvation of the planet. Moore may not have apporved of the movie, but he created the scenario for its premise.

————————–

Marguerite says:

When Watchman first came out I was excited to read it, but when I did I was disgusted by a plot line in which a raped woman falls for her attacker…

—————————

First, she (Sally Jupiter) was already involved with Edward Morgan Blake, the Comedian. She didn’t get raped and then fall in love with her rapist.

So, if there’s a depiction of a female character (hardly depicted as a role-model; her strong and intelligent daughter strives not to be like her, despite following the “costumed hero” footsteps) involved in an abusive relationship, that indicates APPROVAL of that sick dynamic?

(Alan Moore, you sexist reactionary…!)

Next, the abuser is hardly shown as heroic, for all his charismatic bad-assedness: he shoots a woman pregnant by him, for Pete’s sake; it’s implicated he murdered Woodward & Bernstein and maybe assassinated JFK, to boot…

Rather than exploitingly using the scene of an attempted rape for macho thrills, like (yech!) Milo Manara would, it’s shown as ugly, sleazy.

————————–

For women readers it was an affirmation that this venue remained closed to females…

—————————

Rather than the highly complex women characters involved in this intricate, intelligent narrative, I’d think that women interested in making comics would be more turned off by what passes for “females” in too many comics: moronic, pneumatic “fan service” female fantasy figures striking pin-up poses and making “pornface”…

—————————-

Moore’s intial offensiveness further opened the way for the movie to make this a central theme of its narrative i.e. her forgiveness of her rapist was the jusitifcation for the salvation of the planet…

—————————-

No; in the book and the movie (which I’ve only seen once, so details aren’t as clear), it’s the sheer unlikeliness of the chain of circumstances that went into the birth of Laurie Juspeczyk — the “thermodynamic miracle” that the comic’s Dr. Manhattan longed to observe — that moves Manhattan to try and save the world…

(The comedian being her mother’s attempted rapist, BTW, rather than Laurie’s…)

A description of that in the movie:

—————————

Dr. Manhattan…takes [Laurie] to Mars and, after she asks him to save the world, explains he is no longer interested in humanity. As he probes her memories, she discovers she is the product of an affair between her mother, the original Silk Spectre, and the Comedian. His interest in humanity renewed by this improbable sequence of events, Manhattan returns to Earth with the Silk Spectre.

—————————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watchmen_%28film%29

I agree with Marguerite (and please don’t assume that we are always of one mind). I don’t find the “bad-ass” Comedian “charismatic” in any way. Laurie is the product of an “affair”? I think not. I don’t have the book in front of me, but I didn’t get the impression that Comian and Silk Spectre were lovers before he raped her, as if that would justify it in any way.

It is profoundly disturbing that Moore has her mother leaving lipstick on the Comedian’s photo.

The movie took this flaw in the book and made it front and center the rationale for the filmmaker’s altered ending….absurd and revolting. Moore did not approve it. The film was SO wrong in the ways it counts.

The Comedian and Sally have an affair after the attempted rape.

I think the gender politics of Watchmen are actually very thoughtful. I don’t think there is any suggestion that the Comedian’s attempted rape was okay, or that Sally liked it; on the contrary, it’s both brutal and unsexy, and Eddie comes out looking like a ridiculous little scumbag. The fact that Sally should have hated him after that is affirmed repeatedly…it’s a central point of the work. That she ends up loving him is not because rape is okay at all, but because human beings are complicated and flawed. Note that even though she in some sense forgives Eddie, she absolutely refuses to let him have any contact with her daughter. She doesn’t forget, and she doesn’t ever trust him.

I talk about Laurie’s character at some length here, if that’s of interest. Carla Speed Mcneil shows up in comments to talk about how much she appreciated Laurie…not that that negates Marguerites reaction, but it suggests that the reaction of women to Watchmen hasn’t been monolithically negative, at least.

For the ending…I found it disappointing at first, but I’ve grown to like it more over the years. It’s a ridiculous deus ex machina, but I don’t necessarily think miracles are either less satisfying or less realistic than more linear plot solutions. And I thought both Adrian and Rorschach’s ends were moving and well done.

I think it’s fair to some extent to hold Moore/Gibbons responsible for the movie debacle…though only to some extent. Moore was ambivalent about violence; both attracted to it and condemning it. That back and forth is much more pained and genuine than that in, for example, Verhoeven movies — Moore really does detest violence, and he really loves the genre cliches that perpetuate it. Watchmen is both a celebration and a condemnation of the superhero genre; that ambiguity is a big part of its power. Snyder tipped the balance towards the celebration and the violence. He was working from something that was in the original book, but I think he did it in a way that was fundamentally unfaithful to the original.

It’s interesting that Watchmen has been the most controversial entry so far.

The Comedian doesn’t rape Sally. He’s stopped by the Hooded Justice.

Yeah, I’m with Marguerite and James here about the rape plot, although I think Moore had good intentions (the rape is part of his larger goal of showing the real impact of violence). The thing is, this handling of rape doesn’t work because Sally Jupiter’s behavior seems implausible or incoherent. There are a fair number of scenes in Moore’s work with women being abused and tortured. I think this is because a lot of the genre’s Moore is working with are based on the damsel in distress motif. Moore’s goal as an artist is to achieve some sort of artistic distance from the genre material and to comment on it satirically, but often the satire doesn’t work and instead of parody we get pastiche. That’s why so many fans love Rorschach: he’s meant to be a critique of the superhero as fascist but he gives the pleasures of fascism in such a direct form that ironic distance is impossible.

Oops, what Noah said. Anyway, regarding the movie’s version, the camera eye lingers over Sally’s body before the Comedian enters, and then gives a shot of her looking sort of disappointed after the rape was stopped. It eroticizes the rape unlike Moore and Gibbons’ version.

>>>but I don’t necessarily think miracles are either less satisfying or less realistic than more linear plot solutions.>>>

But the plot mechanism has up until that point been so tightly controlled, impressively, almost blindingly, mechanized, that the conclusion is even more jarring than it would be in a more loosely-plotted book. It’s as if one is watching all the planning and preparation of a space shuttle launch, and at the last minute, instead of the shuttle lifting off, a jack-in-the-box pops out the top to “Pop Goes the Weasel.”

Although thinking of it now, I suppose I admire the audacity of it.

“The thing is, this handling of rape doesn’t work because Sally Jupiter’s behavior seems implausible or incoherent.”

But the book explicitly says it’s implausible or incoherent! It’s *not* predictable or logical. That’s part of why it restores Jon’s interest in humanity; because even someone with a god’s eye view can’t understand human behavior — or, perhaps especially, human forgiveness (however qualified that forgiveness is.)

I think there’s definitely something to the Rorschach as fascist argument…but there’s a lot that’s likable about him outside of that as well. He’s the character who cares most about others, in some ways; he’s the one who feels the deaths in New York most fully, for example, and he becomes Rorschach essentially out of empathy. He’s not just sympathetic because he’s a bad ass…he’s sympathetic in some ways because he isn’t the bad ass that the liberal one-worlder Veidt is.

I think seeing Watchmen as parody or satire isn’t exactly right. It’s critique, but the mode of the critique isn’t really satirical or ironic. Again, this makes it pretty different from something like Verhoeven.

The ending might be ridiculous, but it was pretty tightly woven into the plot throughout the book. It wasn’t a deus ex machina.

Again, though, Sean, that’s kind of the point. The book ultimately rejects Jon’s perspective, which is a rejection of that kind of superintricate planning and everything in its place.

It mirrors Moore’s career arc too in some ways…he’s tried to be more improvisational in his later career — with some good results and some less so.

Otherwise, I’m in complete agreement with Noah.

Charles, I think it qualifies as a rape. I don’t know what the legal definition is, but it seems like what happened there is morally rape.

Noah’s got it mostly right, I think… I’m not sure I would even say that she ends up loving Blake however (yes, I know she kisses the picture at the end). He attempts to rape her, she hates him for it…then later they reconnect for a brief (maybe only one time) affair…which she feels guilty about, hates herself for, etc. She tries desperately to keep Laurie away from Blake, and, in several scenes, she makes it clear that she hates Blake, both for what he did to her and for his generally distasteful (to say the least) personality. The point is not to approve of the (attempted) rape, but to acknowledge that people are complicated and it is not impossible for a woman like Sally to both love and hate the same man…something that was true before he attempted to rape her, and afterward. I don’t think she “falls in love” with him after the attempted rape…but that she always had violently mixed feelings about him, which the attempted rape only exacerbated. It’s not a particularly PC storyline, I guess, but it’s clearly not presented as “rape is a good way to seduce women and make them fall in love with you”–It’s presented with the same complexity as the rest of the book. And it’s clear that Laurie, for instance, would never follow the trajectory her mother does.

At the same time, Jeet makes a good point, which is that rape and violence toward women is a consistent part of Moore’s work and a storyline he’s consistently attracted to. He often does so in the context of condemning rape and patriarchy…but at some point these repetitive representations do get a bit disturbing. Both of his comics works in the last year (Neonomicon and LoEG Century 1969) either have rapes or attempted rapes as part of their plot machinery. Reading Watchmen in a vacuum (insulated from the rest of Moore’s oeuvre) makes me see the rape plotline as complex, subtle, fully realized, and hardly the act of sexism Marguerite suggests. Reading it in the context of Moore’s work as a whole give me more pause (despite Moore’s general efforts to be both feminist and queer friendly).

It’s also worth noting that all of Watchmen’s defenders here (including me) are men (and that the vast majority of those who voted for it are as well).

On the other hand, I’ve taught the book to many women, who thought it was great…and even one who wrote a paper about the rape storyline in a positive light.

@Noah. Right, Watchmen is meant to be a critique rather than a parody or satire. But I’m not sure it works as critique because it actually satisfies the generic expectations of the audience: i.e. most readers seem to love it as the ultimate superhero comic, not as a critique of the genre. I think that’s a larger problem with Moore’s pastiche works: he’s such an expert mimic of various genres and knows how they operate that he ends up giving perfect examples of various forms rather than successful critiques.

About the rape plot: “But the book explicitly says it’s implausible or incoherent! It’s *not* predictable or logical.” But simply acknowledging in the story that it’s implausible doesn’t resolve the problem. Anyone who is at all aware of human nature knows how perverse it can be and has seen women and men fall in love with someone who torments and even abuses them. So the topic shouldn’t be off limits to art. BUT if you are going to deal with such a difficult topic you have to do so with great delicacy and care. I’m thinking here of some Alice Munro stories about women who love psychologically abusive men. I don’t think Moore brings anywhere near the care and delicacy the topic requires, so it seem arbitrary and even a bit exploitative. But as I said, I think Moore’s intentions were good, he just didn’t pull off what he wanted to do. The same is true of Watchmen as a whole.

Noah, I think it qualifies as what you previously said it was, “attempted rape.” Morally, the Comedian is the same level of asshole, regardless of his being stopped.

As I recall, the Comedian beats The Spectre bloody when she tries to fight off the rape. Given the potential time space between panels, it is unclear how much could have happened before the Hooded guy comes in to help…it is a violent rape however you figure it.

I like Watchmen, other than the point Marguerite noted (I credit that point with Marguerite’s loss of interest in comics when it came out, so it was not insignificant. She had begun to reappreciate them, but that tipped the scales to the negative), and liked Moore’s ending but the film ruined the entire shebang. I can also point to the way the violence in the scne where the Owlman and Laurie fight the muggers glamorizes violence, completely inverting Moore’s intent. The movie was a stinker with tin cans dragging behind, in other words.

“It’s also worth noting that all of Watchmen’s defenders here (including me) are men (and that the vast majority of those who voted for it are as well).”

As is generally the case in comics, we just had a lot more men than women respond to the poll. (I made a fair bit of effort to try to redress the balance. Said efforts weren’t entirely failures, but that doesn’t mean that I couldn’t have done better.) None of this refutes your point, though.

” I don’t think Moore brings anywhere near the care and delicacy the topic requires, so it seem arbitrary and even a bit exploitative.”

Well, mileage will vary, as they say. As Eric explicates, I think Moore does a lot to explore Sally’s very conflicted feelings towards Eddie.

Eric, the point about Moore’s attraction to rape storylines and violence against women is a good one. He did repudiate maybe the worst instance (in the Killing Joke). I think what Jeet says about his struggles with genre are pretty much on point. I think he is largely successful in Watchmen…and less so in many of his other works (from V for Vendetta on up.)

I have to agree with the general sentiment here that “The Watchmen” does not shine on it’s own integral ‘literary merits’. But does deserve some credit for the way in which it shattered the parameters of it’s genre and helped to herald a new period in North America with the rise of the graphic novel and the triumphal war cry “comics have grown up.”

In hindsight, I think we see that they haven’t, at least not the North American Mainstream comics that were meant by that oft quoted pundit’s phrase. Still ‘The Watchmen’ shouldn’t simply be dismissed as some sort of fascist anti-feminist propaganda piece. It’s clear the author really was striving for something new.

Ozymandias says at the denuement “Do? What am I, some kind of Republic Serial Villain? Do You think I would have told you my plans if there was anyway you could stop them. I DID it. fifty two minutes ago” (working from old memory here. errors are mine)

The characters weren’t merely ‘interestingly flawed’ they were broken. 30 years after the fact we can look at the portrayals of women, the LGBT community, the so called ‘left wing media’ and fascism, and say it’s nothing new, even that it’s obsolete.

It wasn’t then. Not in my opinion, anyway.

Jeet, you seem to be equating ‘critique’ with ‘dismissal.’ There are plenty of genre works that critique their genre, while still being part of that genre. That’s how a genre can grow.

James, “it is unclear how much could have happened before the Hooded guy comes in to help…it is a violent rape however you figure it.” Not really (I link to the page above). Hooded Justice’s voice is the final panel of the rape scene as the Comedian is pulling out his dick.

“Morally, the Comedian is the same level of asshole, regardless of his being stopped.”

Yeah, that’s what I was trying to say. We don’t disagree, I don’t think (for once!)

Jeet Heer sez: Moore’s goal as an artist is to achieve some sort of artistic distance from the genre material and to comment on it satirically, but often the satire doesn’t work and instead of parody we get pastiche. That’s why so many fans love Rorschach: he’s meant to be a critique of the superhero as fascist but he gives the pleasures of fascism in such a direct form that ironic distance is impossible.

Only people with sadistic impulses could look at the violence that Rorschach commits and not be appalled and/or horrified. In the opening chapter he tortures an obviously innocent man by breaking the guy’s fingers one by one. The point isn’t even to get a confession out of the guy; it’s to intimidate the onlookers into giving up information. He terrorizes a terminally ill former criminal who’s long since paid his debt to society. He viciously murders a fleeing former crime boss who is literally half his size and is clearly no longer a threat to him. He kills a child murderer, which some people might cheer, but he’s clearly shown to be in the grip of a psychotic break when he does so. I’m ambivalent about the scene when he napalms the shiv-wielder in the prison cafeteria with the cooking fat. It’s clearly self-defense, but given his obvious fighting prowess, you can’t help but think he could have disarmed the guy in a way that wasn’t so horrific. The only thing he does that I remember being fully justified is when he electrocuted the crime boss’s goon in his prison cell.

I think there are times when you can fault the artist, but I believe there are also times when you can fault the audience. For example, when Crumb plays with racist tropes for humorous effect, his intentions may be different than those who indulge in racist humor without irony, but the effect is largely the same, so it’s hard to blame people who take it differently than he intends. Rorschach, on the other hand, is clearly a monstrous character. To think he’s a cool guy, you have to also think it’s just fine to torture and terrorize innocent people, and to cold-bloodedly murder others who aren’t innocent but pose no danger. I don’t think Moore screwed up with Rorschach any more than Dostoevsky did with his protagonists, or Scorsese, Schrader, and De Niro did with Taxi Driver‘s Travis Bickle. To blame Moore for people taking the character the wrong way doesn’t make sense to me. It seems like blaming Scorsese, et al. for John Hinckley’s attempt on Reagan.

Noah, if you thought KJ was the worst instance, you haven’t read Neonomicon, obviously…

@Charles Reece. Agreed that a critique isn’t the same thing as a dismissal but I think the mild element of critique in Watchmen is crowded out by the very large extent the work simply fulfill up the same old genre expectations, albeit in a much denser and more concentrated form.

@Eric B.: yes, I think my feelings about the attempted rape in Watchmen is influenced by the fact that rape and sexual violence are such recurring motifs in his work. As I said before, I think Moore has good intentions and wants to do a feminist critique of genres. And it shows Moore’s very strong feel for this material that he realizes that rape and sexual violence are in fact a strong thread running through many genres (think of the bug-eyed monsters carrying off the blond damsel in sci-fi). But again I’m not sure that Moore achieves sufficient distance from the material he’s critiquing; its a critique that can easily be read as a replication.

@Robert Stanley Martin. Well, I suppose we’re getting down to the area of individual taste and reaction, but for me Crumb’s satirical intent in his comics on race is very clear, whereas I’m not so sure about Moore’s critical intent because the work so obviously luxuriates in the pleasures of genre expectations. And the thing is, many readers do love Rorschach as a hero, the same way they love Wolverene and the Punisher and countless other psychopaths. But again, I realize that one’s individual reaction might vary; this is definitely a case where critical judgement becomes more subjective.

@Eric B. Yeah, Neonomicon left such a bad taste in my mouth that it’s influenced how I read Moore’s other work.

@Robert Stanley Martin. Also, in the case of Crumb and Taxi Driver, the people who misread these works are clearly loopy or fring characters (neo-Nazis and Hinkley). In the case of Watchmen, it seems like many if not most mainstream readers ended up cheering for Rorschach. That’s a problem in Moore’s work as much as it is in audience interpretation.

Jeet, I deleted your double post; hope that’s all right.

I think the critique of superhero comics is pretty nuanced and thoroughgoing in Watchmen. Rorschach, for example, while sympathetic, is also shown to be a right wing psychotic with massive sexual issues. His secret identity is a delusional street crazy; he eats beans cold out of the tin and smells bad. And as Robert says, you often sympathize with the victims of his violence — especially the “supervillain” (can’t remember his name), who is old and sick and harmless and clearly terrified.

I think Taxi Driver is a lot less nuanced than Watchmen, actually. I’m not really a Scorcese fan in general. Bickle actually gets to be a hero and save the girl in a way that Rorschach doesn’t. It’s ironized in Taxi Driver, certainly…but I think it’s hard to overcome the fact that it’s DeNiro being a star too….

I haven’t read Neonomicon…and now I’m less likely to, I have to say….

The work certainly has merit in terms of complexity of execution, and of course Gibbon’s work is part of what is good about it, don’t forget about him as is so often done. But the main plot points are the responsibility of the scripter, according to DC rules. The fact that the filmmakers made such a botch of it, indicates that other readers might misinterpret it also. Is that Moore’s fault?…maybe, I think his intentions were good but I wish he had thought through the rape issue a litle more carefully.

(edited at author’s request)

Moloch

That movie was godawful, and I think it should be judged on its own merits, or lack thereof. The same plot can be presented in a near infinitude of ways…It’s how it is handled that determines its worth…and they handled nearly everything wrong in that movie. IMO, they handle nearly everything “right” in the book. I also think those who see the book as merely “for its moment” and important historically are wrong. It rewards rereading in the present day and still is a compelling, complex, and provocative book, formally, philosophically, and politically, as RSM writes.

Very interesting debate. I don’t feel qualified to jump in, partly because I’m not that familiar with the book. I have a more general comment, a musing on why I’ve never come around to Watchmen.

I’ve read it, of course, but I never really loved it the way so many people do. I wonder whether part of it is that I didn’t really come to comics by being a big mainstream comic reader through the 70s and 80s and 90s. It seems to me that the people I know who are most blown away by this book are those who are really steeped in comics conventions: all the people who had been reading DC and Marvel all the while they were growing up. When I hear these people talk about Watchmen, they really understand the ways Moore is playing with the form. I remember hearing Charlito and Mr. Phil, the hosts of the indie comic podcast Indie Spinner Rack, talking about how they both Watchmen in the floppies as it was coming out. I think they were both working in comic shops at the time, and so were completely surrounded by that culture. Moore blew both of their minds. I can never experience Watchmen in that way, so my view of it will always be a little impoverished.

As someone who has the floppies from when they came out, I say to that…ouch.

No no! No ouch! I’m saying that I will never have the same rich experience of the book that you will. That was in no way meant as a jab at you, Noah (or anyone else who has all the floppies (carefully preserved in mylar ;) )), but at myself. I read Chris Claremont’s X-Men and TMNT in the 80s, but I often feel like I don’t have the background in superhero comics that I would like to. And it’s hard to go back at this point and fill in 30 years of gaps; much harder than had I been reading at least a handful of titles this whole time. I understand, intellectually, how comics changed in each decade, but I don’t feel it like others do.

p.s. On the plus side, I don’t have to explain away an embarrassing period of my life where I idolized Rob Liefeld.

Jeff is probably right…but it’s not so specific to Watchmen. Anything you read, view, or listen to will be colored by the time, date and circumstances of your experience. Reading Watchmen first when you’re 13-14 (as I was, if my math is right) and then reading it again as an adult is going to be a different experience than reading it for the first time as an adult. Reading it from a superhero-steeped youth will be different from reading it from a different perspective…but that’s the same as anything else. If you read Joyce’s Ulysses at age 18 and are blown away, that will color your reading and your sense of it from that point onward. I don’t see this as the “comics geeks” vs. “regular folks” argument—just that all of us come to all texts with baggage. I’ve had plenty of students not steeped in the superhero tradition who were wowed by Watchmen…and others who could take it or leave it. I don’t think longboxes and mylar is a prerequisite for liking the book…

The first time I heard that some readers think Rorschach is kewl — I thought it must have been a joke. It’s like a plutocrat admiring Mr Burns from the Simpsons. Just goes to show, nobody ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the comic-reading public.

It would be quicker to list Moore’s works that *don’t* feature rape or sexualised violence against women (other than his relatively short pieces). It’s definitely a — let’s be charitable and say — “motif”.

Noah: I’m shocked–shocked!–that this was on your list. -100 contrarian points.

Watchmen is a highly rewarding and great read, the only problem and positive is that it didn’t exist in a volume. It seems there was a misunderstanding of Alan Moore’s commentary on grim and gritty heroes and they became even more popular thanks to Watchmen as it was thought, “People liked that dark book, let’s give them something even darker without any of the craft!” My thought, at least.

Jones, I had Little Nemo too. That’s probably another 100 off….

David…I think Watchmen did have that effect. I think Moore’s even talked about it. He wasn’t pleased.

The thing is, as critiques of superheroes go, I much prefer “Superduperman” by Kurtzman and Wood, which really gets to the heart of the genre is a quite merciless way. Or to pick something that is not a parody — Jack Kirby’s Fourth World series is a quite intelligent and moving interrogation of the combattiveness at the heart of genre and really does ask whether or not its better to flee from violence (as The Forever People and Scott Free try to do) rather than always take up arms (as Orion does — and its significant that he’s organically linked to the embodiment of evil). This interogation of combativeness is all the more impressive because Kirby was by upbring and experience a fighter and played a pivotal role in creating the genre. For me, Kirby’s Fourth World is a much more fertile and more human work than Watchmen, which by comparison seems very mannered and calculating.

Tucker, you are a sweetheart, and you are making me blush (though it’s really Robert’s baby…but I will blush anyway.)

Jeet, I quite like Superduperman. I’m not that into Kirby, but I haven’t read most of the Fourth World, so maybe….

Watchmen *is* really mannered and calculating. That’s very deliberate (of course!) and I think thematized thoroughly. The interesting thing about Watchmen (or one interesting thing) is that it’s very much not just about superheroes, but about comics form. The calculation you’re reacting to, the frozenness, is Moore and Gibbons thinking about the way comics turn time into frozen space. Dr. Manhattan’s superpower is that he’s essentially reading his life as a comicbook. Watchmen (the calculation is in the title, yes?) is thinking about the artificiality of the comic book form, and mapping that onto the artificiality of the way we experience time. It’s not just making fun of superheroes (like superduperman) and not just talking about moral questions of violence (thought it’s both of those things too.) It’s also interrogating the issues you and Sean bring up as weaknesses — that is, it’s not that it fails to be sufficiently planned out at the end, or that it’s too artificial and calculating throughout — it’s that it’s very consciously thinking about determinism and freedom.

I’m not exactly sure where Sean’s coming from…but I mean, to go off something Robert said earlier…are there any post-70s superhero comics you like? Dark Knight? Anything by Morrison? Anything by Moore? I could be wrong, but it seems like you’re just not that interested in superhero comics that take the genre at all on its own merits (rather than as definitive parody), unless it’s Kirby who gets an out because he’s the inventor, so the genre can be refigured as personal expression.

Really, Jeet, you’re moved by the Fourth World stories? Anything asks a lot of questions if you care to look, but it seems to me it’s important how the work addresses those questions and, possibly, attempts to answer them. Watchmen asks whether it’s better to flee from violence or take up arms, too; that’s the difference between Night Owl 2 and Rorschach’s choices. Is there anything as complex or nuanced in Kirby’s tales as the killing of Rorschach and the way Night Owl gets to live with the knowledge of what has brought about a temporary peace? The story doesn’t set up any simple moral resolution to this outcome. I’d say it’s a pretty powerful critique of the way pragmatism and violence underlie our notion of peace itself. Kirby’s never even come close to saying anything as significant or detailed.

And I always wonder if anyone actually finds MAD funny, or if it’s historically funny (you had to be there, but if you weren’t, it’s significant because this is what people found to be cutting edge satire back then). Just seems lame to me, but to each his own.

Rorschach is a “cool” character. I liked reading about him, enjoyed his adventure and what he represented. I like a lot of material about despicable characters. Is it really that hard for some of you to separate what’s enjoyed in fiction from reality? It’s not for me. Even if a lot of fanboys fantasized about doing the things he did, so what? As long as it remains a fantasy, that’s no more troubling than the infinite amount of fucked up fantasies people have in this world. These fanboys probably continued to love their moms and never hit another human after reading and rereading the book.

“And I always wonder if anyone actually finds MAD funny, or if it’s historically funny”

I found superduperman funny, I have to say. I remember reading it in an anthology which was mostly newer stuff and really not knowing what the hell was going on. There’s a great energy to the cartooning, and a great zany yiddishness…I dunno. Maybe it speaks to the last vestiges of my almost completely dissipated ethnic identity.

What you say about pragmatism and violence I really dig. I’ve said this before, I think, but I just adore adore adore the way that in the end it’s the right-wing loonies like the Comedian and Rorschach who basically balk at large-scale violence, while the liberal do-gooder is ready, willing, and able to destroy millions of people for his one-world dream (though, of course, he feels guilty.) That’s really pretty fucking profound, I think, and cuts against Moore’s own politics in a way that I really respect him for.

And though I haven’t read fourth world, I’ve just never seen any evidence that Kirby could come up with anything nearly that politically insightful. Though I do like Kirby’s art significantly more than I like Dave Gibbons’.

Noah — I come late to this discussion, but as a fan of Moore, Kurtzman and Kirby, I have to say I understand why you haven’t seen evidence Kirby couldn’t come up with politically insightful work: you haven’t read the Fourth World stuff. I never read the DC stuff as a kid, but as an adult I’ve come to it with some shock. It takes a long time to understand how to read it, as the dialogue will strike you as awful. It’s non-realist, it’s operatic. And 50% of the time, I still think it actually is awful. But it works mysteriously after a while, like a sledgehammer that fractures diamonds, leaving perfectly planed facets.

If you have time and can really trust that I’m not pulling your leg, the middle-issue Fourth World books have some remarkably complex views on fascism, religion, democracy and wealth. Forever People 8, for instance, links the Anti-Life Equation and capitalism in a pretty jaw-dropping way. Mister Miracle #12, in which a group of wealthy men bet on his death, seems to have sprouted from Kirby’s imagination on the very day Carmine Infantino canceled his books.

But if you’re impatient, I suggest you pick up OMAC. It only ran 8 issues, but even the cover of #1 dives right in with sexual politics that you can’t quite imagine Kirby is insisting on. Issue #2 has a city evacuated at the whims of rich people. It’s dystopian and weird. Unlike Moore (and maybe Kurtzman), he might not have been able to imagine a story where a father would really kill his son (he took that whole Isaac thing pretty seriously). But his moral framework was pretty interesting.

Don’t mind me. I’ll just wait right here while you read those. You might just find them blunt but I see a lot of nuance in there.

The discussion has kind of gone in a different direction, but I wanted to respond to an early comment about Laurie’s origins being the reason for Dr. Manhattan’s change of heart. While that’s true, it’s not just her parents’ relationship that fascinated him, but the implausibility of her existence, the unlikelihood that that sperm and egg, from those parents, would result in that exact person. When she says (paraphrasing from memory here) “but that’s true of anybody”, he replies “exactly”. I always found that to be a really elegant motivation for Dr. Manhattan, somebody who loves the structure and order of the universe, who can see all of existence at every level, to suddenly be struck by the marvelous complexity of life. That’s what I get out of that anyway, not an affirmation of rape or anything.

That’s what I love about this book, and why it definitely belongs on a list like this; there’s volumes to be discovered there, so much to be discussed on so many levels, that it still fosters excellent examinations decades later. Of course, I didn’t put it in my top ten, but my strategy was more of a “favorites” collection rather than an attempt to catalogue the “best” comics, since I don’t think I’m anywhere near qualified to do so. I’m really curious what’s going to come out as #1 now, since I don’t know what could beat out #2…

@Charles Reece: very briefly, I’ll simply endorse Glen David Gold’s description of Kirby’s 1970s DC work, which I share. Those aren’t easy books to read — they have a weird poetry that you have to spend time attuning yourself to, not unlike Blake’s prophetic books. But once your on Kirby’s wave-length they really do speak to pressing human issues in a moving way (moving in part because Kirby’s stories were rooted in his own persoanal experiences as a proud war veteran who had come to oppose the Viet Nam war and also as a creative artist who had to support his family by toiling for crass businessmen.)

Also, I understand why Kurtzman humor might seem dated since it’s the last flowering of Vaudeville but its still pretty hilarious to me, in part because his targets (pop culture and advtertising) still have the same qualities he lampooned.

” in part because his targets (pop culture and advtertising) still have the same qualities he lampooned.”

I’m not exactly sure this is the case, especially for advertising. The internet has really changed the way most people interact with advertising; it’s much more about targeted marketing than the kind of omnipresent ad campaigns which became almost a part of a commodified folk culture. I was reading Beaudrillard’s “A System of Objects” recently, and it was weird how dated it was, in large part because of the central place he gives, and the way he talks about, advertising.

Not that that makes Mad or Baudrillard irrelevant or anything — I like both of those things. But advertising has really changed a lot.

I agree with Jeet. I don’t think advertising has changed much, esp. in the television and radio world. Ads are shorter now…that’s about it. Print ads have obviously changed dramatically, and print in general (esp. periodicals) is dying a prolonged and painful death…but the TV and radio spoofs hold up, if not in their exact targets, in what underlying attitudes are being critiqued.

Comparing Watchmen and the Fourth World is a bit an apples and oranges thing. Moore/Gibbons work in such a different register from Kirby that the premises of the comparison will tend to follow one or the other.

Watchmen is meticulous, cerebral, and emotionally nuanced, the 4th World is visionary, broad, and archetypical. I love both, but regardless of how sophisticated and complex Watchmen is, Kirby at his best is more original, and much more immediately affecting.

As for Mad, as much as I admire what it did and stands for, I think that aesthetically it is a contender for most overrated comic of all time. The artists are often individually funny, but that’s largely in spite of Kurtzman’s willed humor and rather ham-handed satire, which is often dependent on largely and deservedly forgotten artifacts of 50s pop culture.

A story like “Superduperman”, taken on its own, comes off as quite brilliant, as do some of the more daring formal conceits in the magazine, but reading several stories in quick succession, Kurtzman’s formulae emerge and stifle the laughter.

(Am responding to comments as I scroll down and read, so ‘scuse me if I repeat what others have argued…)

————————-

James says:

..I don’t find the “bad-ass” Comedian “charismatic” in any way…

————————–

I personally don’t either, yet am aware that all too many people find “bad boy” types charismatic, attractive.

—————————

Laurie is the product of an “affair”? I think not. I don’t have the book in front of me, but I didn’t get the impression that Comedian and Silk Spectre were lovers before he raped her, as if that would justify it in any way.

—————————

I’m pretty sure they were “involved” before that attempted rape (not to defend the odious Comedian, just trying to be precise), but looking through one of my versions of the book has so far defied my attempts to find corroboration. (Have stopped at where Dr. Manhattan has gone to Mars…)

Glancing at the scene itself, I can see how one would get the impression a rape had happened. (Indeed, I was thinking, have I misunderstood that scene all these years?) But then, in pg. 21 of the first “Watchmen” section, Laurie tells Rorschach, “Blake was a bastard. He was a monster. Y’know he tried to rape my mother when they were both Minutemen?”

…And a closer look at the panels in question show the Comedian, after kicking Sally in the stomach, startling to unbuckle his belt, then interrupted with his left hand still holding the belt, in the same position.

Moreover, in one of the prose excerpts from “Under the Hood,” Hollis Mason recalls, “in 1940 [the comedian] attempted to sexually assault Sally Jupiter…”

—————————-

The movie took this flaw in the book and made it front and center the rationale for the filmmaker’s altered ending….absurd and revolting.

—————————–

If so — I don’t recall that in the movie — it would indeed be revolting!

—————————–

Jeet Heer says:

…The thing is, this handling of rape doesn’t work because Sally Jupiter’s behavior seems implausible or incoherent…

——————————

Alas, all too often human behavior is “implausible or incoherent,” whether in the political realm — people now think Republicans are more likely to protect Social Security? — or the personal, especially where “romance’ is involved.

Does it make sense for a woman whose childhood was hell because of an abusive, cheating, alcoholic father to then spend her adult life in relationships with abusive, cheating, alcoholic males? And to reject men who want to be good to them? Yet, that happens all the time; read “Women Who Love Too Much” for th’ gory details…

——————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

…I think there’s definitely something to the Rorschach as fascist argument…but there’s a lot that’s likable about him outside of that as well…He’s not just sympathetic because he’s a bad ass…he’s sympathetic in some ways because he isn’t the bad ass that the liberal one-worlder Veidt is.

——————————–

He’s certainly more dedicated to justice, that evil — the murder of millions of New Yorkers, however worthy the cause and effect — must be punished…

Moore’s script is careful to give even the Comedian some positive aspects; as when he takes some interest in his daughter, which appears paternal, though Sally thinks he’s being a perv; his cynical cut-through-the-BS perceptiveness when he points out the Crimebuster’s goals (fighting “promiscuity, drugs, black unrest”) won’t mean shit when “the nukes are gonna be flyin’ like maybugs…and then Ozzy here is gonna be the smartest man on the cinder.” And there was his drunken visit to the terrified Moloch, filled with weepy regret over what he’d done…

————————————

Jeet Heer says:

…For me, Kirby’s Fourth World is a much more fertile and more human work than Watchmen, which by comparison seems very mannered and calculating.

————————————–

Sure; could “Watchmen” be any more calculating? Moore himself commenting on its intricate plot workings and linkage with the watchmaker bits; the WATCHmen title…

Moreover, in one of the prose excerpts from “Under the Hood,” Hollis Mason recalls, “in 1940 [the comedian] attempted to sexually assault Sally Jupiter…”

Sally Jupiter was most certainly sexually assaulted, no “attempt”, it was assault with sexual intent…and her humiliation was worsened by the Hooded dickhead who told her to cover herself up afterwards as if it were her fault. What would “Olivia Benson” say about this incident?

Attempted murder isn’t murder. I agree with Hollis.

Ah, but Comedian was a multiple murderer and didn’t have redeeming features IMO, oh sorry, he cried crocodile tears…of course it’s okay he just assaulted her. !!???

No, I’m a bit of an Augustinian about this: the attempt to rape her is just as morally awful as if he had succeeded. She’s slightly better off for not having suffered the whole act, but he’s just as much of a contemptible asshole either way. Legally, you’re better off not having killed your target than succeeding should the law catch you.

Well, I really wasn’t going to say anything here, but since on another thread I began talking about the history of my comics tastes, I figured I should answer Jeff Chapman here:

“I’ve read it, of course, but I never really loved it the way so many people do. I wonder whether part of it is that I didn’t really come to comics by being a big mainstream comic reader through the 70s and 80s and 90s. It seems to me that the people I know who are most blown away by this book are those who are really steeped in comics conventions: all the people who had been reading DC and Marvel all the while they were growing up. When I hear these people talk about Watchmen, they really understand the ways Moore is playing with the form.”

Watchmen was the very first superhero comic I read (or it might have been the Dark Knight, but both at the same time, really), when I was 19 (by the time the last issue came out, I think I was 21). I picked it up on the advice of a friend who also lent me his Love and Rockets issues. I knew basically nothing about American comics at the time, and the couple of issues of Spider-Man I had tried to read a few years before I had thought were totally stupid. And yet Watchmen blew me away, and got me back into comics, which I had largely given up at 13 or so. I was also reading Kundera at the time, and was a film major into Godard and Tarkovsky and Raul Ruiz, so I think I was able to see the sophistication of the narrative devices, etc., from a very different point of view. Which is to say, being a fanboy is not the only entry-point to a comic like Watchmen.

Also, to address something Matthias said, I really don’t buy it that Kirby is much more “immediately affecting.” Again, if I had read Kirby at the same time as Watchmen, I would have probably rejected it. It took me much longer to appreciate the art of Kirby–in a way, an entire aesthetic education beyond what I needed to get Watchmen. (Similarly, for many it is much easier to get into David Foster Wallace than Flaubert, though Flaubert is infinitely greater.)

Pingback: Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons | The Graphic Novel as Literature