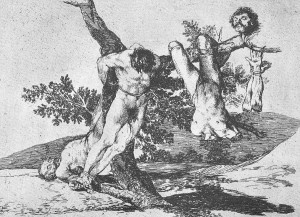

Ana Hatherly, The Writer (1975).

Still in shock after seeing that the comics’ subculture continues as deaf and insular in its aesthetic criteria as ten years ago (since the infamous The Comics Journal’s list) not having moved one iota, I remembered Dwight Macdonald who, in Politics Vol. 2, No. 4 (Whole No. 15), April 1945, wrote:

It would be interesting to know how many of the ten million comic books sold every month are read by adults.[…] We do know that comics are the favorite reading matter of men in the armed forces, and that movie Westerns and radio programs like “The Lone Ranger” and “Captain Midnight” are by no means only enjoyed by children. […] This merging of the child and grown-up audience means [an] infantile regression of the latter unable to cope with the complexities of modern society.

I certainly don’t agree that an infantilization of grown-ups’ cultural habits means that people can’t cope with the complexities of modern society, it may simply mean that comics readers want (for a while) to escape those complexities. Hell, I suppose that they want to escape life itself, or, at least, those parts of life that can’t be depicted by kitsch… Did you notice how death and exploitation are almost completely absent from this top ten’s list (and I don’t mean death of a Daffy Duck kind; Maus and the death of Speedy are an exception)? Have you noticed how lifeless these comics are? (And I mean “lifeless” in the sense of not related to life in any way – Dwight Macdonald also helped me to realize this when he said to Pauline Kael, when they were discussing North-American films: “How did vitality get in there? I mean, crudeness I give you, but vitality? It’s possible to be crude and not vital, you know?”)

I couldn’t agree more with David T. Bazelon, who, also writing in Politics (Vol. 1, No. 4, May 1944), wrote:

“Superman” gives vicarious satisfaction to explicit social frustrations. It cannot be tragic or displeasing, nor can it contain that essential realism which is a quality of all good art. For it has a purpose: this is art in the service of social neuroses. And that service is the meaning of most comic strips… Pearls are produced not by serving but by opposing disease.

Only now did I understand the true meaning of the phrase “comics are not just for kids anymore.” What it really means is that popular comics, even if they continue to be children’s comics, are also enjoyed by adults. With the above phrase and other similar ones people from inside the ghetto of the comics subculture want to sell a false image to the laymen and laywomen (it was now definitely proven to me that the above reading is the right one or they’re lying).

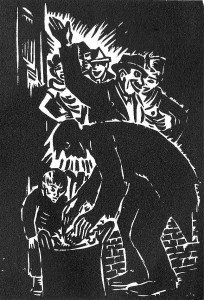

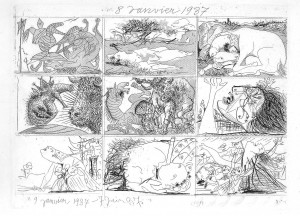

Francisco de Goya, The Disasters of War (published in 1863).

I’m not saying that The Hooded Utilitarian’s top ten list (and beyond) is completely devoid of value. As I put it last May 10 on this very blog: I have nothing against popular entertainment. I also think that a good art vs. bad art kind of black & white view of things isn’t exactly clever or productive. I enjoy a lot of pop pap (Gasoline Alley, for instance) it’s just that I don’t think that it fares well alongside Tsuge’s work or Fabrice Neaud’s work. That’s my whole point, while the pap is canonized meatier work is forgotten.

I suppose that one could say that even meatier work (if that’s possible) is also not included, but there, the infantilization of the reading public is not the only barrier. Essentialism is frontier number two (an even more powerful one this time).

Rosalind Krauss wrote an important essay about how perplexing the concept of sculpture had become at the end of the seventies: Sculpture in the Expanded Field (October, Vol. 8, Spring, 1979). I borrowed her concept of an extended field and applied it to comics.

Rosalind Krauss criticized historicism in her essay. Historicism is also a problem in comics’ expanded field’s case for two reasons: (1) because my field expansion is in great part ahistorical; (2) because some critics view comics as an unchanging art (Alan Gowans) or a posthistorical art (David Carrier).

Frans Masereel, From Black to White (1939).

Arriving here I can only go on after an analysis of what I called, the origin’s myth and the problem of a comics definition.

There are, at least, five cultural fields which can help to expand comics as an art form: (1) Medieval (or older art) painting and book illustration; (2) the wordless engraving cycle; (3) Modern and Post-Modern painting; (4) Concrete and Visual Poetry; (5) the cartoon. None of these fields are linked to comics on the gentiles’ heads. For a variety of reasons they all have problems to be accepted by the comics milieu as well. Let’s briefly examine some of these objections:

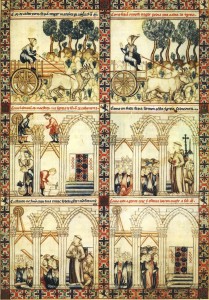

1. Medieval comics (let’s call them that way) weren’t produced for the enjoyment of the people: they weren’t reproduced, they were highly expensive items, they were owned by aristocrats. Since the beginning of fandom comics have been viewed as popular art: a child of the Industrial Revolution and modern visual mass communications (hence: comics were born in America with the publication of a Yellow Kid page in the New York Journal: “The Yellow Kid and His New Phonograph,” October 25, 1896; this is a position that American scholar Bill Blackbeard always defended). Besides this sociological criterion we must add two formal ones in this particular case: the existence of juxtaposed panels and the existence of speech balloons. Denying the latter some European scholars (Thierry Groensteen and Benoît Peeters, for instance) argued that comics started with Rodolphe Töpffer’s first “Histoires en estampes” (Histoire de M. Vieux Bois was drawn in 1827 – Histoire de M. Jabot was published in 1833; Töpfferians who are also print fundamentalists must say that Jabot was the first comic, other Töpfferians will say that Vieux Bois is the real McCoy). In his book The Early Comic Strip (1973) historian David Kunzle argued that the first comics were created shortly after the invention of the mechanical printing press by Johann Gutenberg (Hans Holbein’s Les Simulacres et historiées faces de la mort is among the first books that he cites, but his most famous example is Francis Barlow’s A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish Plot, c. 1682). David Kunzle later converted to Töpfferism (More recently he published a book titled Father of the Comic Strip: Rodolphe Töpffer (2007). Barlow’s two pages fulfill Bill Blackbeard’s criteria, by the way: they were printed, they have a grid, they even have speech balloons or something similar (Robert S. Petersen called them “emanata scrolls”).

Anon., Canticles of Saint Mary by Alfonso X the Sage (c. 1270).

2. Engraving cycles, from Jacques Callot to Eric Drooker, aren’t as difficult to accept (in the comics corpus) by the comics milieu as Medieval illustrations. This happens because they were born from an idea that art should be more democratic: engravings are cheaper than paintings and sculptures. Even so the high / low divide may be a serious objection here. Even if Frans Masereel had a leftist sensibility and his cycles were (are) published in book form, he was a serious painter, he was in the wrong side of this sociological fence. If I defend Picasso as a comics artist the comics milieu calls me a snob and an elitist (doing their usual mind reading they say that I want to include highly regarded gallery artists in the comics canon just to elevate comics’ status). Formal features are a problem also: engraving cycles have no speech balloons or page grids.

Jacques Callot, The Miseries and Misfortunes of War (1633).

3. To the comics milieu paintings and poems (visual or otherwise) are not comics, period. Original comic art has been exposed in galleries, museums, and comics conventions (a strong tradition in Europe’s comics conventions gives original art an important role as an attraction factor), but I don’t mean that. What I mean is comic art meant to be exposed as unique objects on gallery walls. Most people would call these objects paintings inspired by comics. Don’t take my word for it though, the artists themselves call “gallery comics” to what they’re doing. Sorry to indulge in name-dropping, but I mean: Christian Hill, Mark Staff Brandl, Howie Shia. Andrei Molotiu could also be part of this list, I suppose; ditto Paper Rad: they all have strong links with the comics milieu. As for Brazilian painter Rivane Neuenschwander, American painter Laylah Ali and Swiss painter Niklaus Rüegg, I have no idea, but both Ali and Rüegg are interesting examples because, not only did they paint, their paintings were also original art (in the comics sense) for the publication of comic books (by the MOMA and Fink Editions, respectively).

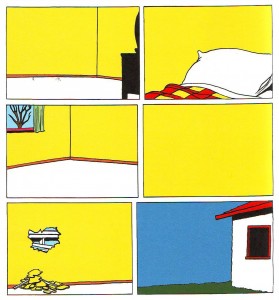

Niklaus Rüegg, Spuk (2004); a Carl Barks comic without the characters.

4. During the fifties Brazil was at the avant garde of poetry. Inspired by Stéphane Mallarmé’s Coup de dés, Guillaume Apollinaire’s calligrammes, Dadaism, Ezra Pound’s Imagism, Haroldo and Augusto de Campos, Decio Pignatari, Pedro Xisto and others created Concrete poetry. In a Concrete poem typography and the pages’ space is as important as words. Sounds are more important than meaning (or new meanings are born when words are reorganized on the space of the page and reinvented). Concrete and visual poetry viewed as comics may prove that comics without images may exist in the same way as comics without words.

Álvaro de Sá, Process-Poem (c. 1967).

If we consider stained glass windows as comics (something that is not as far-fetched as it seems) Medieval comics were also meant to be viewed by “the masses” even if they weren’t printed (David Kunzle opines differently though: “A mass medium is mobile; it travels to man, and does not require man to travel to it.”) As for grids and speech balloons it’s possible to find said features in Medieval comics, believe it or not. Here’s what Thierry Groensteen wrote on the Platinum List (Jan 18, 2000):

Danielle Alexandre-Bidon, a specialist of the Middle-Age, has given a lot of evidence of the fact that comics existed in the medieval manuscripts, during the 11th, 12th and 13th centuries. Hundreds, if not thousands of pages, with speed lines, word balloons, sound effects, etc. The language of comics had already been invented, but these books were not printed. After Gutenberg, text and image were not so intimately linked anymore, and one could say that the secret of comics was lost, until Töpffer rediscovered it.

This is revealing: even the most fervent defender of Töpffer as the “father of the comic strip” says here that he “rediscovered it.” This is something like saying that Columbus rediscovered America (he couldn’t discover it simply because he found people already living there when he arrived).

The comics origin’s myth is essentialist: it’s an arbitrary choice that’s based on an equally arbitrary definition (the latter precedes the former). (And I’m sure that I’m not the first one to say this, elsewhere or around here.) The two more common (or so it seems to me) kinds of definitions are based on social (comics must be reproduced and distributed to the masses) and formal premises (essential characteristics of comics are sequentiality, word and image relations, the word balloons, the juxtaposition of the panels, etc…). Social definitions of comics have two problems: (1) The sorites paradox applied to the concept of “masses.” If one grain of wheat doesn’t make a heap two grains of wheat do not; […] if three thousand grains of wheat don’t make a heap three thousand and one grains of wheat do not; etc… When do we stop not having a heap to finally have one? This paradox can be applied to print runs. (2) Social definitions of comics are usually used to deny that Medieval comics are comics (they aren’t reproduced). What I say is that they must have been reproduced at some point because I’ve seen them and I have never seen any original drawings. There’s a third point: how come an original comics page is not a comic, but an exact repro is? Leonardo de Sá cleverly argued this point saying: the original art is not a comic the same way as the repro of a painting is not a painting. Not bad, I would say… but… using Nelson Goodman’s theories about fakeable and not fakeable arts, painting is one-stage autographic while comics are n-stage (my theory) autographic. That’s why a repro of a painting is not a painting while the original art of a comics page is a comic. Formal definitions of comics have problems also; I’ll mention two: (1) Any formal definition arbitrarily chooses some features and forgets others. This means that, if I chose to say something like “the speech balloon is essential to comics” (oops, there goes Prince Valiant) or “word and image relations define comics” (oops there go “mute” comics out the window) no comics exist at all. Why? Because all comics have panels without speech balloons, without words, etc… A comics reading experience would be something like this: now it’s a comic, oops, now it isn’t, etc… (2) All art is based on experiment. More inventive artists are always pushing the limits of their art forms. Comics are no exception, but if we put a formal corset around them what happens is that: (1) we lose some very important artistic achievements (some who defend comics exactly because they’re mass art couldn’t care less, obviously, but I, for one, do) and (2) we seriously limit the creativity of the artists who chose to create comics. Another problem is that we can’t look back to, let’s say, Charlotte Salomon, and view her work as comics (again: some who defend comics…). It seems that all comics have sequentiality, but even this point was argued by Eddie Campbell in a discussion with yours truly many moons ago: he included one panel cartoons in the comics concept. Me?, I have no definition of comics whatsoever. I prefer to say with Saint Augustine: If no one asks me, I know what they are; If I wish to explain them to him who asks, I do not know.

Charlotte Salomon, Life? or Theater, CD-Rom (2002 [1940 – 42]).

So, denying essentialism we can look back or look around and find great comics. I have no solution for the ahistoricity of the expansion in time or social space. Picasso didn’t view himself as a comics artist (even if he liked comics) and the art world around him didn’t either. However… if older art historians say that Picasso’s Songe et mensonge de Franco (Dream and Lie of Franco) are engravings (which they are, of course) more recent ones (Juan Antonio Ramirez, for one) say that it is a comic. This means that we (even if part of this “we” doesn’t belong to the comics milieu) may look in unexpected places and notice multiple instances that can be considered comics (Frans Masereel is a no brainer by now, for instance; I’m sure that Paleolithic painters didn’t call “painting” in the modern sense to what they were doing). As for comics as an unchanging or posthistorical art it may be true (I have my doubts) if we consider it as low mass art, but aren’t we excluding heaps of alternative artists, then? I’m trying to be reasonable, but, to talk frankly, I’m tempted to say that this is utter nonsense.

I didn’t vote for any artists and work on the expanded field (maybe Martin Vaughn-James’ The Cage counts as part of it; Robert tells me that there were indeed some votes in said field: Cy Twombly, Max Ernst, and a few others), but if I did almost all my ten choices would be in that category, I’m afraid… Who, in the comics’ restrict field can rival Callot, Goya, Hokusai, Picasso? No one, I’m sure… Not even George Herriman and Charles Schulz.

Pablo Picasso, Dream and Lie of Franco (1937).

Note: huge chunks of the above text were previously posted on my blog The Crib Sheet.

Watchmen definitely talks about death and exploitation (it has a lot to say about imperialism, for example.) I think Schulz’s portrayal of school speaks to the way that we oppress children…and he certainly talks about anxiety and aging and sadness.

Though just in general I don’t agree that death and exploitation and sadness are more real than joy and humor and happiness, or that the second isn’t a fit subject for art.

My list had a mix of expanded field and restrict field (Hokusai as well as Peanuts.) I don’t actually think that the expanded field is automatically and in every way better than the restrict field; I pretty definitively like Peanuts better than Picasso (not least because Schulz has a very thoughtful and nuanced take on his female characters, whereas I find Picasso’s misogyny both irritating and predictable.) Hokusai and Beardsley (who were on my list) are amazing…but I think Ariel Schrag’s Likewise and Marston/Peter Wonder Woman (also on my list) are amazing too.

picasso’s run on JLA was the BOMB

See, I thought the whole Cubed Lantern saga was kind of idiotic. But mileage varies, I guess….

What happened to the illustrated books? :D

I’m not an essentialist when it comes to language (or much of anything, really), but I’m noticing a few problems in your anti-essentialism:

1. A comics page is autographic, but not a comic isn’t (normally). It does matter when you purchase an original page if it’s a reproduction. When you buy a particular comic — say, Watchmen — it’s still that comic even though there’s thousands of copies out there. Watchmen is allographic. as is each recorded performance of the 9th. Now (getting to the exception), a first edition of Watchmen issue 1 can be forged, just like the first pressing of Karajan’s first performance of the 9th might be. But this exception matters only to the collector-recipient, not to the definition of art itself (which is Goodman’s point — the forgery here is still Watchmen, still the 9th).

2. Most importantly, I don’t see how 1 has any effect on whether something’s a token of comics art. The difference with fine art or whatever is that the reproduction is no less authentically a token of the art work being reproduced than the original page art. This is different from a reproduction of a painting. A Stephen King story is still the same Stephen King story whether you’re reading it as a mass market, hardback or his original type-written pages. The same goes for Watchmen. The same doesn’t go for looking at Rembrandt’s paintings. You’re not looking at a reproduction of Watchmen in a comic, but Watchmen. The original pages of Watchmen are still comics, just not auratically so. If one wishes to be essentialist here, one would say the essence is in Watchmen’s reproducibility, Rembrandt’s in the painting itself.

3. The sorites paradox isn’t a paradox if one believes all boundaries arbitrary. We know that Achilles will eventually overtake the tortoise, so how is that the math involved suggests otherwise? The representation isn’t matching up with the reality. That’s the paradox. This isn’t a social problem, since such a socially derived boundary is ontologically arbitrary: e.g., we call grains a heap somewhere around 3000 grains (but is that really the capital-I Idea of ‘heap’?). I think a better version is do you have the same house if you dismantle it brick by brick and then put it back together in an adjacent lot? That’s a problem for a painting, but not Watchmen. If you, Domingos, believe that you can draw the boundaries of comics wherever you feel like it, then it doesn’t matter whatever you call a comic — so why commit so much time to the question? (Maybe you believe it serves some pragmatic utility to do so — then you get into problems of whether this agenda of yours is really, nonarbritrarily, useful to do.) If, however, your intuition is that Watchmen is still Watchmen after such a reconstitution, but Rembrandt’s painting isn’t, then you can’t dismiss the reproducible definition of comics.

remove the “not” from “but not a comic isn’t.” I’m sure there are more mistakes.

This is really inchoate, but I have a gut feeling that while the “comic’s restricted field” as you define it has yet to produce much on a par with Hokusai or Ernst, it has demonstrated its potential to do just that. When that will happen, I don’t know. But I get a lot out of those glimmers of hope. My top ten list sort of reflects this. I largely voted on works that suggested the form had more to offer than what it had offered so far, and in some cases more to offer than the selected works themselves. This is a weird way of saying that, for me, comics are about hope and not nostalgia. This is an insight that making the list put into perspective. Thanks for giving me the opportunity.

Domingos, I love you because you’re so fun to argue with. For instance, Scott McCloud offers the best, most succinct definition of comics available and you still insisted on researching midieval printing techniques. I love that about you man! It’s hilarious!

Seriously though, it is important to not conflates precedents and ancestry with early work. All art is built on foundations of art before it. As well as informed by art around it. Picasso famously enjoyed comic strips, but he was not a cartoonist. Egyptian hieroglyph writers weren’t making comic strips, they were making hieroglyphs, period.

I see on paper what you mean in your endless quest for “mature” and “sophisticated” works. But I always have the sense that you miss the forest because the trees are in the way. I mentally cannot process “what is comics” conversations. Because it is clear as day: comics are comics. If that’s not enough, Scott McCloud nails it with an elegance unseen anywhere else.

As for what constitutes “good” comics, I don’t know. I DO know and am absolutely positive that whatever is quality won’t be determined by whether a work is intended for children or for adults. None of that matters. Fantastic works in other fields have been intended for children, for adults, for both and for neither. That is not ever a factor. Nor is “escapism.” Fantasy, the fantastic, reality, none of it matters toward whether a thing (in this case, a comic) is any good.

None of those above factors have the power to raise or lower the status of a work of comics. Maus is NOT a better comic than Bone. Not in any reality or by any reasonable metric.

I’m not sure in what way that “I suppose” is meant, but I just want to point out that, factually, I was a member of the gallery comics group from the beginning–I was a member of the blog (still am, I suppose, though it is largely inactive nowadays), participated in the “gallery comics” session at CAA in 2006 which was kind of like the coming out party for the genre, exhibited as part of the group along with Mark and Christian in the Out of Sequence show, and a piece of mine was used as the frontispiece for the IJOCA roundtable on the subject.

Also, abstract comics, which straddles comfortably the comics and gallery art world (as well as having been adopted by many visual poets recently), should also be mentioned as part of this expansion of the field.

More: I’ll buy the expanded history of comics into Renaissance woodcut broadsides, etc.–the Kunzle canon, if you will–but I’m a bit wary about including Goya et al. in this. In a way, there is a direct line of development from popular Renaissance prints to Topffer to the Yellow Kid that just isn’t there with Goya or Callot. My main problem with this further expansion is the same one as with Scott McCloud’s adoption of Egyptian wall painting as comics: they belong to a larger category–call it narrative art, or sequential narrative art–of which comics is only a subset. On the other hand, comics has developed narrative techniques, also coming in from literature and film, that are not used in this larger field of sequential art. So comics is a subset of this larger set, but it contains formal aspects not existent in the rest of the set, and which connect it to other art forms all together.

I illustrate this in my classes by comparing Hogarth’s the Rake’s Progress with Mr. Vieuxbois. The Rake’s Progress, like much traditional sequential art, is made of self-sufficient tableaus; Mr. Vieuxbois, on the other hand, uses juxtaposition, incompleteness, ellipses, synecdoches, etc., to create what Barthes might call a “relay” from image to image that simply isn’t there in other sequential art, except very occasionally and almost as if by accident (I know it happening, for example, in a Fragonard drawing series that was dispersed after Frago’s death and was not re-gathered and published as such until the 1940s, so there’s no way it could have influenced the evolution of comics!)

Don’t get me wrong: Goya and Hokusai are among my favorite artists, even my favorite sequential artists. But I would not categorize them in any way as makers of “comics”–which is a different form from what they were practicing. But, if anyone reading this wants to look into it, I would recommend even more strongly Goya’s sketchbook drawings (they were all published together in a volume), which contain sequences that are even more clearly narrative than in any of his print cycles. From the same period, I would also recommend Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo’s “A New Testament” and “Life of Pulcinella” drawing cycles, which were each published as self-standing volumes by Adelheid Gealt (or by Gealt and Knox). Also Fragonard’s “Ariosto” cycle of illustrations–about which I wrote, umm, somewhere. (I think in an old TCJ post that I can’t find right now.)

As for Hokusai, I actually wrote a paper in grad school on sequentiality in the “One Hundred Views.” (I submitted it to Noah, but I guess he felt it was not right for this site.) Yet, its sequentiality is mostly formal, as I argued, which is not something that was influential in comics until very recently (well, ok, abstract comics again). If you were to find in Hokusai’s work a more direct ancestor to manga (as in comics, not Hokusai’s sketchbooks, which are not sequential), it would be in his “Life of Buddha.” I keep hoping that will be reprinted someday.

Again, as to more recent painters, I would rather put emphasis on artists who clearly are aware of and somehow use or refer to comics grammar, layout, etc., in their work, such as Pierre Alechinsky or even Philip Guston–rather than, say, Twombly, whose narrativity is derived directly from traditional sequential art, without a detour through comics. (And yes, I know you just mentioned Twombly as someone else’s choice, but I’m commenting, I guess, on the whole issue…)

Lastly, I think Charles brings up a good point, which I think works with Domingos’s rather than against it: painting, drawing, sculpture, etc., are autographic because they are defined by their physical media. Comics is defined as a structure, independent of (physical) medium. As such, it can be reproduced from medium to medium, as long as the structure stays the same: so the fact of it being reproduced, printed, is not important, but its potential reproducibility is. Also, being a structure, maybe we should not define it as a medium but as an artform? This may be just semantics (everything I wrote here may be just semantics), but I think this dilemma may point out the insufficieny of calling comics a “medium.”

Actually, I just didn’t realize you were submitting that essay for HU Andrei; I thought you were just showing it to me personally.

Let me email you….

I’m confused by Darryl, who claims that McCloud provides a good definition, but then rejects Domingos’ broad claims. McCloud includes hieroglyphics, stained glass windows, Trajan’s column, and medieval manuscripts. Domingos takes issue with Kunzle’s attachment to mass reproduction, not with McCloud’s much broader definition. Rather, Domingos seems to want to take the McCloud definition seriously…as opposed to just a jumping off point for discussing the Yellow Kid and his ilk.

No Eric B…

The part where McCloud defines comics is a succinct moment. When he starts going off about scrolls and shit, we can disregard as wool-gathering.

Andrei,

I don’t agree with this:

“so the fact of it being reproduced, printed, is not important, but its potential reproducibility is”

Everything is potentially reproducible. The question is whether that matters in the relation of the reproduction to the source. For Watchmen, it doesn’t. For some high art painting on a wall in a museum, it does. There’s this robot out there that can replay famous piano performances (Tatum, Rachmaninoff, Gould) in an amazingly precise way. The music is the same piece of music that was originally played, but the performance is not. It would take a pretty radical AI enthusiast to say that this is actually Gould et al. playing. It’s possible that someone will design software and a robot that’ll allow the same thing with famous paintings some day. My intuition on this is that the precise (maybe even exact) replication wouldn’t be the painting, that the reproductive procedure matters to what we call the original/real art piece. This is not the same with Watchmen. The reproducibility has no bearing on the real Watchmen “piece.”

Additionally, I think the question of medium is somewhat separate from all of that. The Watchmen motion comic that is now out there on video is only a comic once we’ve extended the definition of ‘comic’ to fit it. The comic has been altered in structure to accommodate the medium-specificity of film. But maybe you’re saying film isn’t a medium either, but an artform? I’m not seeing much of a difference there, I guess.

“The reproducibility has no bearing on whichever token of Watchmen you have being the real thing.” is a better way of putting that last sentence in my first paragraph.

I strongly second Andrei’s point that “medium” is an unsatisfactory word. I’m open to “artform” — but curious what the other parallel art forms would be (i.e., what else is in the same class as comics conceived in this way…)?

This is one of those places where I feel like comics theory oscillates between art and language without getting to meaningful synthesis: in the sense that comics are “writing with pictures” then one reason “medium” is unsatisfactory is probably related to the fact that “medium” is not a particularly useful term for talking about writing.

I sort of buy “structure” — but what is the place of language in that structure? Jason Overby has a wonderful comic which contains no images — only words, which end up becoming images, but do not stop being words. I can’t buy describing that as “writing with pictures,” but it’s obviously not quite the same thing as literary prose. Domingos raised (and then did not discuss) illustrated books. Someone else ages ago in some comments thread mentioned concrete poetry — should that also be part of comics “extended field”?

Just — whatever the “extended” field turns out to be, it can’t look entirely to art or to visual culture, or it will miss a significant facet of what makes comics powerful, and will overlook the full range of material that comics can engage with critically and imaginatively to expand and enrich what’s in the restricted field.

I still like my definition.

“Comics are those things that are accepted as comics.”

Domingos,

This gives me a lot to think about, but I worry that you’re

in danger trading exceptionalism for essentialism here, where there’s something innately “comics” about certain cultural products, and that whatever it is, we can identify it when we see it.

That doesn’t have to be an essentialist position though, Nate. That is, the “comicness” can be a function of social and historical communal knowledge, rather than something inhering formally in the work itself. So we can identify it when we see it, but because it’s part of an agreed upon (albeit blurry) field of knowledge.

I just feel like defining aesthetic fields like this isn’t all that useful. It seems like it’s maybe better to just say, “there’s a generally agreed upon sense of comicness; the restrict field restricts what you’re talking about to work that’s towards the center of that field; the expanded field lets you wander further out.” It’s not clear to me what the point is in trying to nail down a definition more clearly than that.

Noah — where are you drawing the line between “defining” a comic and “theorizing” comics? It seems to me that there are definitions in the service of theory — parameters you posit in order to cluster things together and illuminate them and frame questions about them — and there are definitions in the service of canons: like when people have said to me that Anke Feuchtenberger can’t be my favorite cartoonist because she doesn’t make “comics”. The former are what Delany calls “functional descriptions” I think; whereas the latter are more conventional definitions. I can agree with your last couple of statements if we’re talking about conventional definitions, but I think functional descriptions — competing ones, and the arguments they generate — are vital.

Darryl: have you ever read Samuel Delany’s essay about Understanding Comics? It’s funny, because he says many nice things about McClouds book — but then basically completely eviscerates his argument. McCloud bores me, I have to say — but the Delany is just marvelous.

I’m happy to have people talk about how comics function and how they’ve worked historically. I just don’t know that doing that in the context of definitions seems all that helpful.

I mean…theoretical discussions of novels aren’t necessarily obsessed with defining novels, are they? Or discussions of poems with poetry; I just don’t see a definition as where you need to either start or end.

Charles, I think you think we’re disagreeing, but we’re really not. By “reproducibility” I simply meant that a comic can be reproduced in any other (or many other) media and still be a comic–and still be the same comic. A painting cannot be reproduced in an other medium without ceasing to be a painting, and it cannot be reproduced even in painting without ceasing to be the same painting. If I see a scan of a comic, I’ve read that comic. If I see a photo of a painting, I haven’t seen that painting; if I see a mechanical reproduction of the painting as another painting, I still haven’t seen that painting.

Comics are therefore designed to be reproduced in a way that paintings are not. Think about it this way: Warhol, say, makes a painting that includes a silkscreen of a Nancy daily: from looking at it, you can read the comic, no problem. He makes another painting that is a reproduction of the Mona Lisa; obviously, if you look at it you’re not seeing the Mona Lisa. So “comicness” survives reproduction, but “paintingness,” or “original-paintingness,” does not. So the category of “comic” has a different ontological status than the category of “painting.” And I would say that is because it has reproducibility (without loss) inscribed within it.

As for film, that is a totally different can of worms. I would argue it IS a medium, inasmuch as (from my point of view) the relationship of a projected film to its reproduction on video is rather similar to the relationship of a painting to a photograph in a book. Some elements (which I would argue are essential to the experience of a film) don’t survive in translation to a different medium (video). Other elements do, and so I suppose the very definition of film as a medium or as an artform depends on which elements you think are crucial to it, and which are not.

Well, definitions of the novel are more complex than the kinds of pithy definitions people tend to put for for comics, Noah, but there’s been a lot of defining. Originally people spent a lot of energy trying to figure out the difference between a novel and a “romance”. The formalists focused on characteristics; Ian Watt says (in 1957):

Michael McKean begins his more theoretical work with a chapter chock full of ruminations on the history of definitions of the novel and related genres.

Definitions in comics tend to be about identifying comics’ precise uniqueness, rather than situating them in relation to everything else, but comics is such a polymath artform, engaged with so many other things, that those kind of “essentialist” definitions always seem to leave important aspects out.

Which is why I think Andrei challenge over the term “medium” is right. Film is both a medium and an artform, but not all art-made-with-the-medium-of-film precisely resonates as the artform we generally call “film”. So do you have to automatically call a work a “film” just because it is made with film?

Or, say, can an object be both a comic and a painting? Can you use the medium of paint and canvas to make the artform of a comic — i.e., something made with the tools used to make paintings? Could you use the medium of film to make something that when it’s finished is not “cinema” but “comics”? Or any other medium? Comics is definitely not a medium in that sense — but it is an artform. But what exactly does artform mean? That’s an even looser aesthetic category…one that easily fits comics, and seems likely to be fecund for comics (certainly more so than medium) but without much theoretical specificity.

That’s why I was asking for other examples of what counts as artform, to start to distinguish where the line is between “artform” and perhaps “genre” or something else. In practice, there is so much overlap among all these things, but the job of theory is to tease them out — although different theories will tease out the line in different places, creating different functional descriptions. That conflict and cacophony leads to theoretical richness — you don’t want there to be one correct pithy definition because if there is, that’s a sign of the artform’s limitations and imaginative impoverishment. But it doesn’t mean the impulse to define should always be resisted — just never relied upon.

Caro–

Domingos did mention visual poetry, which if I’m not mistaken essentially includes the older notion of concrete poetry, so yes, definitely part of the “expanded field.”

You mentioned not looking only at visual art, which I agree with (as I said myself, comics include narrative devices which do not come from earlier visual sequential art, but rather from film or literature), so I’ve been wondering what those could be. Off the top of my head, Topffer basically comes from a tradition of (ultimately) Laurence Sterne imitators, so “Tristram Shandy” would definitely have to be in there. Film is almost too obvious to mention, but look at Eisenstein’s article that discusses “editing” in Dickens. I’d say it’s that kind of literary “editing,” shiftings of attention, that in part accounts for the difference between comics and traditional sequential narrative art. But now we’re getting in a discussion of influences rather than simply the “expanded” field. Beside Tristram Shandy, what earlier works of literature would you say could be included here? “Un Coup de des,” maybe?

My own expanded field would include both the Codex Serafinianus and Spencer-Brown’s “Laws of Form.”

“Other artforms”–poetry, maybe? (Wikipedia: “poetry…is a form of literary art…”). A more obvious answer would be visual poetry, which has exactly the same relationship to reproducibility, and therefore the same ontological status, as comics. But maybe that’s too easy.

On the other hand, I wonder about abstract art or conceptual art, or performance art for that matter. They are not media (the medium of abstract art can be painting, drawing, sculpture, etc.), but neither are they genres, though they are sometimes referred to as such. They are categorially different from, say, history painting or landscape painting. So, artforms? Certainly forms of art…

“the “comicness” can be a function of social and historical communal knowledge, rather than something inhering formally in the work itself.”

True enough, with the caveat that this social knowledge often includes a lot of unexamined assumptions about what “art,” “comics” “porn,” or whatever, is. I’m thinking of the “I know it when I see it” move, which implies an essential (if maybe ineffable) quality.

Anyway, having re-read the post I realized I misread essentialist as exceptionalist, which caused me to post what was a misguided comment. Oops.

The real challenge for comics scholarship, I think, is to give into the complexity and start looking for models that can account for how we got to the “now” of comics. Recent work in book history suggests this is a productive row to hoe. I’ve often thought the most productive way to understand what makes a comic a comic would be a historiographic approach, i.e., tracing histories of the field for narrative patterns that reveal the underlying assumptions about what comics should be, or what we imagine them to be.

The what is comics questions seems tied up with what I understand to be the essentially imagined history of the medium, a fan mythology that prefers celebrate assumptions rather than question them, toward the end of constituting a community (and in so doing shut others out).

Props to Domingos for pushing back.

A “novel” initially was meant to articulate its “newness.” Somehow we got stuck on the term, though…

Darryl, you’re wrong about McCloud, though. The “woolgathering” is woolgathering about his definition. All those historical things he refers to work fine under his definition…thus the woolgathering. (Fun to write woolgathering this many times, though). Woolgathering….woolgathering…Ok, I’m done. Nope. One more. Woolgathering.

Andrei — so would you consider “prose” to be at the “artform” level, along with poetry, or is there no prose artform, since “novel” is a genre, I guess more like history painting?

I clearly just skipped the paragraph before “Process-Poem.” Let me think about your first response some more before I respond to it…it’s interesting though, to see how loosely visual poetry is defined by wikipedia: “Visual poetry is poetry or art in which the visual arrangement of text, images and symbols is important in conveying the intended effect of the work.” That’s not all that distinct, is it, from your notion that comics is a structure? The definition is open enough that comics could actually be thought of a subspecies (I’m resisting “subgenre”) of visual poetry…

I gotcha, Andrei. I’m confused why you think we’re agreeing with Domingos, though. Unless I’ve misunderstood, he’s arguing against reproducibility being a necessary distinguishing feature of comics.

Noah: “I’m happy to have people talk about how comics function and how they’ve worked historically. I just don’t know that doing that in the context of definitions seems all that helpful.”

I agree. It was the Goodman that got me going. I think there’s a lot to be said for the cognitive-Wittgensteinian notion of the prototype: an averaged center to a conceptual constellation that shifts as new features are added to the mix through use. That’s another way of saying we know X when we see X. That’s not all there is to it, but the view seems to contain a lot of truth. Unsatisfying to those yearning for essences, though.

Yes…I’m a little uncomfortable being Wittgensteinish; he’s so utilitarian…but that’s where I come down here I think.

I have to say, spending a lot of time trying to distinguish novels from romances sounds pretty horrible…but I guess everybody’s got a thing….

There are formal bits that really interest me in comics, but I don’t feel like they define comics, or need to be the essence of comics. More like, they’re things that lots of comics do, in such a way that I’m interested in thinking about things that aren’t traditionally comics as comics when they do those things. Like Escher or Lacan.

Domingos and Andrei: To my mind, the most important section of Krauss’ essay on the Expanded Field is the section on artistic practice, which is related to her work on the post-medium condition:

So — what is the logic tying together the expanded field of comics? If you were going to build a Piaget square for comics like the one Krauss builds for sculpture, what would the central binary be? Would it be — as I sort of allude to above — image and language? Drawing/writing? Or some concept even more removed from medium than those? And, given the “essentialness” of reproducibility to the comics form, does it tie into the square Krauss suggests for painting?

I guess — these are the questions that are most in my way answering your question about what prose literature I’d put in the expanded field, Andrei; I’m just still not entirely clear what that field is. It’s a related but separate set of questions, I think, from the ones about comics as an artform…

Charles–Domingos was arguing against the empirical fact of a comic having been reproduced as a necessary criterion for comicness–not, as far as I can tell, against reproducibility in general. Indeed, when he argues, correctly, against Leonardo de Sa, that the original page is a comic too, I’d say that reproducibility is implied inasmuch as the comicness survives the change of medium (from drawing to print, or rather retroactively from print to drawing…). Since print-only theorists define comics as a (physical) medium, it seems to me that Domingos is arguing against medium specificity; indeed, “medium-independence” might be another term for, or related concept to, reproducibility.

Caro 1: if poetry is an artform, would I call prose an artform? Maybe not prose as such, but specifically literary prose.

Caro 2: I was asking about what works of literature you would include in the expanded field since you had argued that it needed to be expanded in that direction. I would still assume there was some kind of intuition behind your remarks, intuition that does not need to wait until a strict definition of the expanded field is given… Rather, that definition would have to base itself on such intuitions.

And, honestly, if we’re starting to make logical squares, I’m so out of here… :) In any case, defining the expanded field need not mean reducing it to a set of essential characteristics, to a single logic. Wittgenstein’s notion of a family of games comes naturally to mind here–especially if we think of comics proper as an individual who might contain genes coming from its forebears (literature, traditional narrative art, drama, etc.), and shared with its cousins (visual poetry, art books, and so on), while those forebears and those cousins need have no genes in common.

Hmm, maybe Andrei, but he wasn’t too clear about that with his one-stage allographic (painting as potentially reproducible) vs. n-stage allographic (comics as reproducible). I assumed he didn’t use ‘autographic’ for a reason. And I think it might be important to clarify that this is a discussion about a necessary feature, not a sufficient one: reproducibility is a feature of many things that aren’t comics, but is it always a part of comicness?

Noah, then you might like the horribly named Theory Theory of Concepts. I’m fond of it.

Ok, so Andrei, I think you’re basically inserting “artform” as a classificatory category in between “medium” and genre? So you’d have prose language as a medium, and literary prose as the artform (along with, say, journalistic prose and popular prose ?), and then the familiar genres. Verse would also be a medium, with poetry as an artform (along with blank verse), and the genres things like sonnets or epic, etc.

I think that’s maybe not quite right — prose poetry i guess would be an genre under literary prose? Hard to make poetry and prose discrete…maybe the medium should be text and the artform literary language, [along with journalistic language and popular language] with prose and verse being umbrella genres that overlap and have all the subgenres like blank verse and novels?

The formulation really does work elegantly for comics: Comics is a multi-media artform — the media, as an example, pen&ink plus prose, with comics as the artform, and the genres the expected literary ones as well as the emerging fine art-inspired ones like gallery comics.

Is that right?

More on Expanded Field to come…

Caro said:

“That conflict and cacophony leads to theoretical richness — you don’t want there to be one correct pithy definition because if there is, that’s a sign of the artform’s limitations and imaginative impoverishment.”

Absolutely. Delany’s argument, I’d say, in a nutshell.

Domingos’ post is quite stimulating, and the ruminations on the “expanded field” that is has inspired are very illuminating. Thanks!

Quite a surprise to find myself saying that, because, at the outset, the MacDonald quotation struck me as exactly wrong:

“This merging of the child and grown-up audience means [an] infantile regression of the latter unable to cope with the complexities of modern society.”

Nonsense, and argued merely by assertion. MacDonald is of very limited use critically when confronting comics, precisely because of his penchant for that kind of elitist assertion. Ditto Bazelton’s claim that realism is an essential “quality of all good art” (unless by realism what is meant is a certain truthfulness rather than a style of representation, but even there the terms are slippery). The reason people keep calling these kinds of claims “elitist” or “snobbish” is because they are, well, elitist and snobbish.

But I’m all in favor of the expanded field and the pushing out of horizons, which I take it is the main thrust of Domingos’ post. I have to wonder, though, about Domingos’ air of aggrieved surprise in response to the HU poll. Does it not seem obvious that a poll couched in terms of “comics” will produce results that favor a traditional notion of “comics”?

Charles, what’s the source of that quote? (It’s not in the post, right? I searched…)

Umm … Search harder?

:)

Oh, that’s WEIRD. Apparently if I have clicked in the comments when I start the search, Firefox only searches the comments and the “recent comments” feed. I have to actually click on the post before I search in order to find text in the post.

But if I’ve clicked in the post, it does search the comments.

I had no idea! Thanks for fixing me. :D

Hi all:

Thanks for all your comments! I was afc for a while because comics weren’t part of any of my priorities in Skala Eressou, the lesbians’ paradise and mine too.

Charles:

This is not an answer to you, it’s just a comment explaining how I used Goodman. Since he doesn’t talk about comics I searched for a kin art in terms of reproductibility (is that a word?): engraving. Here’s what Goodman says in page 114: “printmaking is two stage and yet autographic. The etcher, for example, makes a plate from which impressions are then taken on paper. These prints are the end-product; and although they may differ appreciably from one another, all are instances of the original work.” This describes the comics’ process for me. The reason why I said (adding “my theory”) that comics are n-stage is because I thought about facsimiles which are impossible in printmaking.

Just now read your reply, Domingos, that’s interesting. It would seem Goodman disagrees with me on the application of his own theory. Here’s something he didn’t think of at the time he wrote that, though: printing can now be sourced from a digital file (Gibbons, Quitely and others now draw on the computer, for example). Does that mean that comics and printmaking are no longer 2 stage autographic, that the digital source is autographic (that’s hard to believe), or that (as I think) print art isn’t accurately described as autographic, 2-stage or otherwise. I’d like to read your thoughts on this, but it seems to me that allowing comics to be autographic turns film into an autographic art, too, with the original film strip being the source. So why isn’t the original script for a book then autographic? And on and on …

Charles:

The answer to your last question is very simple: allographic arts use notations, autographic arts do not (the word “script” that you used is really the key to the distinction). A digital file is as good a source to a two stage autographic art as a piece of paper. I see no problem there…

Well, there’s this: “a work of art is autographic if and only if the distinction between original and forgery of it is significant; or better, if and only if even the most exact duplication of it does not thereby count as genuine” (that’s from Languages of Art, but I just copied it from here). As I argued above, I don’t see a difference between any copy of a comic. I know that people are always arguing about authenticity of Warhol prints and the like. That’s not the same as a comic book, though. Is the collected Watchmen less authentic than the pamphlets? I suppose you could say that the original pages are the original book, but that’s playing around with words (and you could do the same with original manuscripts). The use of notation isn’t all there is to it: if I paint a bunch of letters and hang it on a wall, that’s still not allographic.

A little more:

It’s been a while since I read some of this stuff, so I probably should’ve refreshed my memory before replying originally. Reading a bit more in that link, an etching is autographic only if the original plate is used. I’m not sure that accurately describes the case of comics, though (I don’t think it does, in fact — color, for example, is typically added in the computer, even if the drawing was on paper, so where’s the original?). But, to get back to the stuff about the sorites paradox:

Notice how the distinction between autographic and allographic arts is not the same as the distinction between arts that are singular and those that are multiple. Etching, for instance, is still autographic although multiple. Incidentally, this could allow Goodman to account for the interesting hypothesis, advanced by Gregory Currie (1989), of superxerox machines capable of reproducing paintings in a molecule-by-molecule faithful way. Such technique of, we could say, cloning could be accounted for in Goodman’s terms as transforming the art of painting from singular to multiple and yet without changing it from autographic to allographic.

I applied Goodman’s theories to comics. I have no idea if he would agree with me or not. I argue that the original color (even if it’s done on a computer) is part of the original art. I view every recoloring in every reprint after that as fake. This means that, talking about reprints, I only accept facsimiles as genuine.

As for the cloning, here’s what Goodman has to say (113): “Let us speak of a work as autographic if and only if the distinction between original and forgery of it is significant; or better, if and only if even the most exact duplication of it does not thereby count as genuine.”

Well, after a bit more reading, I’m still thinking he would not, that a comic is more like literature than painting: “[L]iterature is not autographic […] Any accurate copy of the text of a poem or novel is as much the original work as any other.” [from “Art and Authenticity”] If I destroyed all the original art of Watchmen after scanning it into a high-res digital file, would using that digital file make any less an authentic Watchmen comic? Regardless of whether you’d say the product was a fake, the more important point is whether that matters. I’d say it doesn’t, it’s still authentically Moore and Gibbons’ Watchmen, and thus comics aren’t an autographic art.

What digital means to all of this is something along the lines of what’s the difference in using a computer to draw or write? The same 1s and 0s underlie them both. Is it possible to have an autographic digital art?

When you’re scanning it, you’re reproducing it using the original art as a source. That’s the same thing as destroying the original plate of an etching.

And… again: the visual part of the comics use no notation. I agree that Goodman would probably compare comics with words to (218) “The architect’s papers […] a curious mixture.”

Oh… and I wouldn’t call the Watchmen that you mention above a fake at all. I would call it a fake if someone (even Moore or Gibbons) added or subtracted art or dialogue or if someone recolored it.

But, D, notation matters in the sense that it’s being used for performance, that the notated work is missing something without being performed. A novel’s manuscript doesn’t require performance, but it’s still part (a token) of an allographic work (the text). As long as I retype every word with the same punctuation and in the same syntactic order, that’s the work. Similarly, as long as I copy the panel arrangement, Moore’s text, the balloons, Gibbons art with his coloring, etc., that’s Watchmen. That’s not the same for a painting.

I haven’t read much of this yet, but here’s a pertinent essay from a philosopher:

The Ontology of Comics

Nope. If you copy Watchmen you’re doing a fake because that particular instance of the book wasn’t reproduced from the actual work of Moore, Gibbons, John Higgins.

The existence of a notation means that the work is unfakeable, hence: allographic. A score implies that a performance isn’t more genuine than the next one and the first edition of a book is not more genuine than those that follow it (114): “There is no such thing as a forgery of Gray’s Elegy.”

Thanks for the link: I was ripped off.

Haha, yeah, he definitely agrees with you (p. 15), but I’m sticking to my position. You’re both wrong. Talk to you later.

Can’t quite leave it alone: in record collecting, one typically wants a pressing as close to the first as possible, because of audio fidelity, the source is more pristine (and the vinyl tends to be better produced). That doesn’t make recorded music autographic, since even the arguably shittier sounding later pressings are still tokens of the same music. I’d say the same is true of comics, even where, say, the Marvel Masterworks has altered the coloring or whatnot. They’re still Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s FF, Thor, etc.. One might have a preference for the first editions, but the latter ones are no less authentically those stories than using some font you don’t like to see alters a novel. The quality of the printing or the source of the printing (a digital version of the art, say) doesn’t alter it’s ontological status. Changing the source does, however, matter to etching.

Now, Meskin says that a copy of a comic is a (“referential”) forgery unless “it was mechanically copied from the original plate or art or some other genuine copy.” Assuming we agree that an LP isn’t autographic, how would you distinguish that view from the Meskin’s? Of course, direct transcription of the LP’s contents (say, my playing all the instruments and singing) would be a fake, but that’s a red herring. That fake is questionable as a forgery — I’d call it a cover, ditto my directly transcribing all of Watchmen. This argument over ontological status of comics has to do with mechanical reproduction. And a mechanical reproduction of the original or genuine source of a painting, namely the painting itself, makes what’s reproduced a forgery or a copy with an ontological difference. The fact that I can scan a beautiful version of Watchmen with a good enough scanner and it’s still Watchmen makes it allographic in the same way I can mechanically reproduce a LP not using the master tape, but a store bought copy of the LP with the product still being a token of the LP’s content (Zeppelin 4 or whatever). It might not look or sound as good, a collector will certainly balk (might even call it a fake), but it’s still the comic, still the album. Legally and collectorwise, it might be a fake, but that doesn’t make it ontologically so.

“the first edition of a book is not more genuine than those that follow it”

right. are you saying later editions of Watchmen are less genuine than the serialized pamphlets?

Your example confuses a particular performance with the musical composition. I agree that Goodman must have been thinking about classical music when he said that music is allographic. A performance of, say, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony by the Berlin Philarmonic conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler is not more genuine than a performance of the same composition by the same orchestra conducted by Herbert von Karajan. Conversely, if we talk about other genres (Jazz music, for instance), music is autographic. Meskin acknowledges this when he cites Jerrold Levinson. In my blog I also discovered an autographic piece of literature: Graham Rawle’s Woman’s World (but the author subtitled the book “A graphic novel,” whatever that means).

Nelson Goodman may have been wrong (he fell victim of his own prejudices, but don’t we all?, for him classical music was music, period), but he was not wrong when he underlined the importance of the existence or absence of notation. Rawle’s case is quite interesting: if the author chooses a certain type he or she is transforming literature in (partly) a visual art. That’s what Peirce called a diagrammatic sign. This happens all the time in comics (that’s why lettering is notation, but, at the same time, is autographic).

Again: I wouldn’t call the copy that you mention a fake: comics are not engraving. I talked about that when I said that “comics are n-stage (my theory) [autographic.]” (I commited a terrible mistake in my post above: I wrote “allographic” in the sentence above when I, obviously, wanted to say “autographic”). The mistake is corrected now.

Thanks for the heads up: I also fell pray of my own biases: to me “a book” means “literature.”

One more thing: the FF are not Stan Lee’s and Jack Kirby’s only. The letterer and the colorist are also the authors. Alter their work and you produced a fake.

There are instances where it could be argued a work in it’s published form is the fake. In a mainstream commercial setting if a comics story came off a creators work table written, drawn, and lettered, but was then passed through an assembly line for reproduction, in my opinion the production process almost without exception weakens the integrity of the work.

holly: I don’t agree. The production process is part of the work, for better or for worse. I didn’t mention editors above, but they have an important role too, of course.

Which is the fake “Greed” (the film)? The one released or the one not released?

Domingos

Conversely, if we talk about other genres (Jazz music, for instance), music is autographic.

I don’t know about that: what’s the autographic instance of “Take the A Train”? I think you’re taking the collector fetish for autography.

Re: your Rawle example (great blog entry, btw), he’s using language in a non-notational way, so I agree that such usage could be autographic (people have their own handwriting style). I’m not sure that a slight altering of the original lettering in a Marvel’s comic book really changes much, though. It’s not Dave Sim, after all. Contrasting Rawle’s “graphic novel” with a comic, I’d ask is his original source book the work, or is the published version? The tape and glue, are they always reproduced? Which brings me to:

the FF are not Stan Lee’s and Jack Kirby’s only. The letterer and the colorist are also the authors. Alter their work and you produced a fake.

When I look at an old FF comic, I see a lot of dotted color, but when I look at the original pages that Kirby drew on, I see no color, other than the occasional blue lines or whatnot of writing on the border (which aren’t there in the published comic). If the colorists are part of the authorship here, then surely you don’t see those pages as the original “plates.” That’s a bit odd: the pages that Kirby’s pencil touched aren’t the work, e.g., the FF comic. I’m just repeating myself at this point, but it matters a great deal that an authentic print uses a particular physical master source, but that’s not true with comics. I do concede that comics, due the analog need of reproducing the art, are closer to the autographic side than something like literature. It’s just that, to me, their status as a reproducible art — that the work is the comic book you hold, not the pages, etc. leading up that comic book — makes them allographic. And, to borrow an analogy from that Encyclopedia entry: if Pierre Menard were a comics fan and succeeded in creating an image-for-image, word-for-word, color-for-color, etc. comic identical in every way to FF#1, we’d have another token of FF#1 (“albeit with his actions Menard may have suggested a possible, new interpretation of that work”).

I’m not completely convinced of my own view, so it’s been really fun arguing with you. You can have the last word if you want it.

holly:

Interesting question, but I’ll answer with another question: which is the real Greed? The eight hours one, the four hours one (cut by Stroheim)? We’re talking about different versions of the same film, not fakes. It’s like various stages of a plate to go on with the printmaking analogy. Fakes (recoloring old b & w films, for instance) can only happen after the film was released. Same for comics.

Charles:

I’m no Jazz expert, so, I’m bound to talk about things that I don’t really know nothing about (besides, music isn’t my thing), but doesn’t Jazz music rely on improv? Another musician copying such an improvisation seems odd to me, but, as I said, what do I know?

The original art for comics may be multiple. It’s not just the page that the penciller and the inker drew and the letterer wrote. Sometimes the color is on the page too though (it’s called direct color). Coloring processes changed a lot over time (today the colorist most likely works on a computer) which, as I said in my blog post, poses an interesting problem: if we don’t want to reprint a fake do we need to reproduce the dots? In my view yes, because if we lost the original art, the printed books may be the only direct connection to the original art that we have. No if the publisher has access to the engraver’s proof sheets and uses them with contemporary technology (as in Fantagraphics’ Prince Valiant recent series).

I’m glad that you liked my blog post. Thanks!…

Just to answer your question: I was maybe a bit unfair with using an example from a jazz musician known for his compositions, Duke Ellington. But, still, jazz often relies on compositions and then improvises around them. And then there’s the more improvisational reaches of the genre that just start to play around a lead (I love the stuff, but there are probably better terms for what I’m trying to say). Anyway, didn’t Goodman cover this, that even if music is improvised and then named as a work, it could be notated and played by someone else, thus it’s still allographic?

Now I’m out.

And, of course, I fucked up: Billy Strayhorn composed Take the A Train.

Greed may not be the best example because the eight hour version was screened in San Francisco. The four hour edit would also be legitimate, but what about the general release which as not cut by Von Stroheim? And is the version “restored” using stills a bigger fake than the two hour cut?

Certainly there are many bastardized films. The Wedding March, might be a better example. In some cases the official release has even had scenes added in by another director at the demand of the studio. Queen Kelly for example.

Charles: “didn’t Goodman cover this, that even if music is improvised and then named as a work, it could be notated and played by someone else, thus it’s still allographic?”

I don’t think so.

holly:

I must say that I love Stroheim. Even butchered his films are great. I remember loving The Wedding March the first time that I watched it, but… A work of art is the result of many forces. Some are related to a single artist, some are not… I’m the first in line to defend an artist’s integrity. Did Irving Thalberg have more basic worries like making money? Yes, he did, but, in so doing, he helped to shape Stroheim’s films (or, to be more accurate: the films directed by Stroheim). Nothing leads me to believe that what he did was to produce fake films. He was producing films, not reproducing them.

All artists face constraints. Most of these constraints are accepted by the artists and even viewed as their personal expression: their times’ available set of styles, world views, techniques, etc… Money is just another of those constraints. Maybe the worst one (I call Capitalism the worst dictatorship that ever existed), but it’s just one among many…

Just to address the jazz question; jazz is really a post-recorded music phenomena, and as such the individual recordings are really the thing, not the compositions. To say that this is just a collectors issue sort of elides the fact that in a post-recorded music genre like jazz, the line between collectors and listeners is really blurry.

Who is playing on a jazz recording is as important — often more important — than who the composer is. And since it’s improvisational, individual dates are important too. I mean, composers are important, but nobody who listens to jazz is going to tell you that any composition is interchangeable. It’s all about the singer, not the song — to such an extent that it kind of is nonsensical to talk about a composition as an original version. Coltrane playing “My Favorite Things” is not about the composer.

If anything, this is even more the case for rock or pop records….

Now I’m wondering if any of that was actually helpful or pertinent…but oh well.

The essentialist approach to defining comics strikes me as being utterly specious. It only serves the priveliging of certain writers’ favourites over all others.

The concept of “family resemblance” is much a more useful, pragmatic, and progressive approach to semantics.

There is another important part of Blackbeard’s definition, not mentioned in your article: recurrent, named characters.

“… (A) serially published, episodic, open-ended dramatic narrative or series of linked anecdotes featuring recurrent named characters.”

This seems to be the basis for his insistence on The Yellow Kid being the original instance of comics. The necessity of recurrent characters, or seriality of any kind, is clearly meretricious and requires the exclusion of almost all EC comics, just as one prominent example.

http://konkykru.com/earlycomics.html has many examples of pre-Outcault comics, including some which utilise panelisation and speech ballons. (e.g. from 1830: http://konkykru.com/e.heath.html )

There are even some pages there featuring Ally Sloper, a recurring named character who first appeared in 1867.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ally_Sloper

He didn’t speak with balloons, but many of his antics could easily be described as comic strips nonetheless, as indeed they were at that time.

Some have claimed that first periodical publication which can readily be identified as a comic, or comic book (mainly containing comic-strips) appeared in Scotland in the late 1800s. I saw it, in a BBC documentary about Scottish comics creators, and it did seem to be a comic.

But, no. Essentialism, with all its hazards, reigns supreme in mainstream comics history.

How very peculiar.

Yes, on the matter of definitions I will choose Wittgenstein over Bill Blackbeard any day. That recurring characters thing is especially absurd (so much so that, as you noted, I even forget that it exists). Blackbeard’s is a formal definition that includes the content (!). I know that “form is the content” is one of my mantras, but this is ridiculous…

Essentialism reigns supreme in mainstream comics history because it’s no history at all: it was written by fans who knew nothing about how to write real history. Being collectors their only aim was to uncritically record as much as they could (I usually say that they were fact collectors). Apart from that hagiography is the norm. What baffles me is that the only real comics historian in existence, David Kunzle, also thought that he needed an essentialist definition before starting his monumental two tome oeuvre.

Pingback: Weird and wondrous comics of Aleksa Gaji?: Comics in the expanded field (works 2011-2013) | Sr?an Tuni?