I began writing this piece before the announcement of the depressing verdict in the case between the Estate of Jack Kirby and Marvel Comics and by consequence Stan Lee. In the simplest terms, Marc Toberoff, the Kirby Estate’s lawyer claimed Kirby was the originator of all the properties in question. Toberoff’s strategy was the same as that he deployed for the heirs to the Superman creators Jerome Siegel and Joseph Shuster in their fight to reclaim copyrights from DC Comics, a division of Warner Brothers Entertainment. He lost. Even the most ardent Kirby fan acknowledges that for a while the two men, Kirby and Lee, collaborated comfortably to produce seminal comics in the American canon and all but a few claim that to make Kirby the sole creator across the board is not defensible. The Kirby lawyers overstepped the mark in the attempt to regain control of early copyright and collect remuneration for the proceeds from early works that were subsequently developed. For those of us on the sidelines, perhaps more painfully the result legally diminishes Kirby’s place in history.

All parties have been less than candid in their presentations.There is plenty of blame to go around, which I am forced to say even as an artist and long time supporter of the Kirby camp. The result of this case will affect all who deal in creative and intellectual property, whether literary or otherwise and unfortunately the Kirby lawyers mishandled what should have been a landmark case in the protection of creative properties.

Some suggest that Kirby himself signed his rights away when he agreed to create as “work for hire,” but I would point to a parallel in the music industry where early recording artists similarly originally gave up their rights. They later won cases to reclaim them because they could not have foreseen the new media that would offer alternate distribution platforms and uses for their creative property. Contract law, which to validate any agreement depends on a “meeting of the minds,” might be applied as Kirby could not reasonably have imagined the rapidity and growth of media technology. Kirby though often accused of having an overly vivid imagination when it comes to Sci-fi, was not actually clairvoyant.

The shambles that has ensued after Lee’s courtroom default from history because of his contractual and financial allegiance to the company leaves the creative world a sadder place. Revisionist history diminishes all. This dispute between artist and Marvel is sublime in its scope. The immense edifice of the corporation dizzies the individual.

Another aspect of this debate, which has become so reductive in its claims of creative primacy, suggests that the idea is the only criteria for original creation. Even if hypothetically Lee originated characters, I would argue that where there is no previous model then the artist creates the image and reifies a concept. If there is no model to work from, then one must create the original figure, which henceforth will become that model. Pushed to a logical limit, one could point to the fact that though Bernini did not originate the myth of Apollo and Daphne, he certainly produced his original sculpture. His rendering of the narrative is creatively unique.

On the other hand, in the consideration of the various statues of “David” created by numerous artists, Donatello, Michelangelo and Bernini for example, one might say that these are all “works for hire” and only the divine source of the narrative is significant, with the plot supplied by the church. The church, like any other giant institution or corporation has interests in controlling its mythologies. This labor, artistic or not is at the service of a larger ideology.

As Louis Althusser, a psychology-driven sociologist says, “assuming that every social formation arises from a dominant mode of production, I can say that the process of production sets to work the existing productive forces in and under definite relations of production.” I shall return to Althusser momentarily, but for now I wish to affirm that both Kirby and Lee were proud to work within the ideology of American capitalism. In the legal case, neither side stands or challenges American capitalism on ideological grounds overtly, despite a strong undertow of class and labor issues that largely go unspoken. And while I have framed many of the issues within the sphere of artistic production, certainly both Kirby and Lee saw themselves in the business of selling comics. Elsewhere, Althusser helpfully casts light how problems might arise undetected by two men who had not only served in the military as a system of American ideology, but had become a part of the means of production for that ideology.

Ideologies are perceived-accepted–suffered cultural objects, which work fundamentally on men through a process they do not understand. What men express in their ideologies is not their true relation to their conditions of existence, but how they react to their conditions of existence; which presupposes a real relationship and an imaginary relationship.

Kirby perhaps presupposed himself a participant in a post WW2 America that had fought and earned the right to play fair. He imagined that a handshake would suffice as he saw himself a part of an institution that in reality would later belittle his role. Lee working in a family business, saw himself as management rather than worker and this self-elevation transferred to how he interpreted his creative relationship, which gave more import to words, as though they signified his class and its rights and its sanction.

In comics, men of words hire men of images. The historical system of patronage is codified by capitalism and is supported by critics who use words and instinctively “read” comic text as though it is merely supported by images that stand in for verbal metaphors. In the arena of commercial art, class ties to and debases visual literacy and text reigns supreme. (Comics are annexed from Art History, which might disrupt labor relations by elevating the artist in relation to the writer. This would threaten an instiutionalized ideology in which the journeyman artist is kept in his imaginary place.)

Terry Eagleton expresses another intersecting perspective that helps illuminate how the comics industry positioned itself in a self-perpetuating Western capitalist society:

‘Mass’ culture is not the inevitable product of ‘industrial’ society, but the offspring of a particular form of industrialism which organizes production for profit rather than for use, which concerns itself with what will sell rather than with what is valuable.

Kirby and Lee became engaged in a culture that conflated their cultural output with their commercial product. Their value as artists was secondary to their commercial potential. This is a trap that concerns all work in the arts and in scholarly fields as the pressure to deliver a “product” can easily obscure the “value” of one’s work. Kirby and Lee worked within let us say, “popular” culture and there were undoubtedly certain sacrifices to deadlines. However it would be difficult to imagine that either worked deliberately below his potential “in the definite relations of production” of their industry and society.

Longinus on Where Words Count, Stan Lee as a Prince of Rhetoric.

I had intended with the second in my series about the sublime and comics to return to the (fragmented) work of Longinus to help elucidate the relationship between Kirby and Lee. Longinus, a Greek teacher of rhetoric or a literary critic who lived in the 1st or 3rd century AD, wrote a treatise “On the Sublime,” which discusses language in relation to the production of the sublime. His observations, which are delivered in the form of a letter, in fact represent the underpinnings of a textbook of advice for the writer and probably speechgiver, on the creation of sublime text, though much of this latter advice is lost. His interest is in identifying and delineating the elements of writing that operates in the presence and construction of sublime language and pointing out the pitfalls that can derail the would-be rhetorician. He offers:

The Sublime leads the listeners not to persuasion, but to ecstasy: for what is wonderful always goes together with a sense of dismay, and prevails over what is only convincing or delightful, since persuasion, as a rule, is within everyone’s grasp: whereas, the Sublime, giving to speech an invincible power and [an invincible] strength, rises above every listener.

Longinus further says the sublime rhetoric of the speech-writer resides in “great thoughts, strong emotions, certain figures of thought and speech, noble diction, and dignified word arrangement,” which might also begin to expose possibilities in the interactions between words and ideas in comics. All of these elements one would hope to discover in the pages of a heroic narrative of the superhero comics, but might be particularly explicit in a production such as Jack Kirby and Stan Lee’s “Thor.”

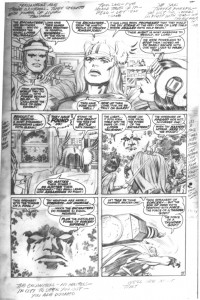

When I presented the Kirby /Lee “Thor” page in my previous discussion of the sublime, I did not address how the notes in the outside borders written in Jack Kirby’s hand might inform the final text/speech in the finished word balloons written by Stan Lee. Here on face value, it appears as though the initial “ideas” and their visual rendition come from Kirby, but are reconfigured by Lee. Lee’s diction transforms Kirby’s side notations with amplified language and words that are of a suitable weight to match the visual narrative and content. This is achieved as he uses repetition and emphasis to create a heightened language that inspires and moves the reader. Thor and his cohorts never articulate outside of their quasi-archaic parlance.

For the reader, the strange tone and historicity add weight to the narrative. This language is that of great men doing great things. Most of us as youth ( although I except that somewhere there are probably religious groups who still use the “thee” and “thou” of second person singular ) only experience this type of highly wrought diction in the formal realm of “literature,” as in Will Shakespeare and John Donne, or in the script of the Bible. Lee’s écriture, the grammar of which delightfully and frequently deviates from recorded “English” & its real variants is meant to be understood as a heroic language and it is Lee’s generosity of style that allows the reader to formulate this language internally in his or her own linguistic terms. In other words, one is able to participate imaginatively in the construction of the characters’ syntax and diction. Further, the reader is able to engage and even deploy the system of language, to think without fear of error within the construct of Lee’s linguistics. The effect would be comical beyond its acceptable level of dramatic kitsch if the entire comic were to be spoken in Kirby’s New York slang circa the Bowery Boys. As the language is transformed by Lee it is able to support its authority within the ideological tenor of received historicity.

All the same can one say that Lee is dangerously close to the ridiculous, but that as children this giant nuance escapes us? Perhaps his flexible English reinforces an independent American ideology and the desire to escape from the vestiges of British ligusitic tyranny, or to become a “noble” American writer.

In the border notes in Kirby’s recognizable hand, “Thor says – I’ve heard tales of it – well—let em come,” written clearly in the American mid-century vernacular. This is transformed by the rhetorical skills of Lee who gives: “The Enchanter from the mystic realm of Ringssrjord!…It has long been prophesied that they would one day strike at the very core of Life itself where Asgard doth hold reign!” Issues of class manifest themselves in the “superior,” declarative language of the Gods. The vernacular of Kirby’s voice must be corrected to reflect that of the upper class heroes.

Both men recognize their own class in relation to the content. Kirby, who remained proud of his heritage as the son of a Lower East Side immigrant, does not write his text in “Thor-speak” but uses his working class action voice to express his ideas. This forces questions about how class operated between the men. Implicitly, art is produced in a strangely abased position in the social hierarchy of production. Art appears to be the tool of the intuitive, untamed mind, while writing evidences intellectual precision and authority. Logocentrism is bound to class structures and it seems Thor-speak claims the authority of the noble class and that its writer represents a conduit to this class with its values of duty and honor. Remember as Longinus says: “The great speech maker speaks great thoughts.”

In his essay “Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses,” Althusser suggests capitalist society reproduces the relations of production in such a way that this reproduction and the relations derived from it are obscured. Capitalist exploitation hides its presence from direct sight, but the ideology of capitalism, which is imaginary, interpellates us in such a way that we recognize our place in that ideology and accept the rightness of it. This occurs through a series of erroneous recognitions and assumptions that follow a fallacious logic… It must be so because it must be so, right is right and so forth. Althusser’s explanation of this process runs: Ideology calls out to (or hails, interpellates) individuals. A (metaphorical) illustration of this: Ideology says, “hey, Joe” and Joe responds, “Yes?” In doing this, Joe recognizes himself via ideology, situates himself in the position it tells him he is in. Since he knows he is, in fact, Joe, just like Ideology says he is, ideology seems natural and obvious, not ideological.

Kirby scripts Stan Lee's dialogue as Funky Flashman with Scott Free in Mister Miracle 5, November 1971.

In the panels above, Funky Flashman tries to manage Scott Free, who suggests that they collaborate on a mutual enterprise. Flashman internalizes and operates within the ideological system, even as he toys with transgressing boundaries which he would like to assault through language. Further, he uses words as a device of control, he does not recognize his own position within the ideology. Flashman describes how his words elicit emotion and comprehends this advantage as one of power. He ironically recognizes himself as a subject and self-imposes through pleasure and duty his own imaginary inherited desire to work. “Oh I feel it the terrible, self-fulfilling call to work!! The song in my blood that says “Work Funky!!! Work and be productive!”

Kirby as the writer of this text, lampoons the writer, a thinly-veiled depiction of Lee, and frames Flashman as an effete, decadent. But his mockery does not release either from the cycle of production. Althusser states that free will is essential for this continual state of self-delusion (false consciousness) to persist. The subject must feel that he is free to act as he chooses, but his self recognition within the social structure ensures that he will continue to be productive and remain within an ideology that he believes he has created and sanctioned. As we read comics we are identifying ourselves as within an ideology. Whether as adult readers we see comics as escapist “lower” literature, a developing underserved art form, or we read them as kids and adults who internalize their ideological positions, we recognize a cultural production when we look at and read a comic and as such we have agreed to become part of the Ideological State Apparatus.

Althusser suggest that capitalism is held in place by Repressive State Apparatuses (RSA), the Law and State. As in Marx, Althusser posits that a superstructure of political and legal repressive systems stands on an economic infrastructure with repressive state edifices (RSA) supported in turn by Ideological State Apparatuses (ISAs). ISAs are found in the educational system, the religious system, the family, the cultural systems of literature, the arts, sports. While the RSA controls by force, the ISA functions through promises and seduction. Althusser suggests that education is the dominant ISA, because school teaches “know-how” wrapped in the ideology of the ruling class which enbles the subject to adhere to their role in class society. Althusser further notes that children are given into the hands of institutions of education to be indoctrinated for years, from pre-k -til…well some of us never leave.

Without making this a full blown discussion of Althusser, one can draw from his position the idea that a subject freely submits to subjugation through ISAs. The Flashman and Scott Free passage points to the irony of the belief in “work” creative or otherwise, yet simultaneously recognizes the value of work as inherently worthy. Scott Free promotes a silent acceptance of the workingman’s role, while the entitled Flashman proclaims about the difficulties of creative work.

As readers of this passage we willingly accept the need to fulfill our role as workers, even as we privilege class and even as we admire the nobility of the work ethic. Intriguingly, as readers we willingly identify with Scott Free, the self-recognized “actual” worker and accept an appellation that sets us within the mythologization of honorable worker. The comic book here is an ISA, by which we willingly reinforce statifications of class and labor, which directly maps on to how we prioritize text over image. The debate that surrounds Kirby and Lee slips past any consideraton of equality of medium into issues of class and artistic stratifications.

Colonel Corkin’s Sublime Call to Capitalism.

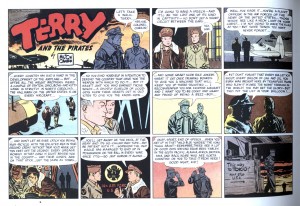

Elsewhere the rhetorical power of comics literally moves from the page into the Congress as the wartime Terry and the Pirates’ Colonel Corkin speaks to his young charge a speech of such sublimity that it moves the reader who cannot help but respond to the noble sentiments expressed. This at least is the opinion of the Hon. Carl Hinshaw of California, who addressed the House of Representatives on Monday. October 18, 1943. Here the comic is celebrated as a vehicle of ideological repression. Hinshaw s remarks follow thus:

Mr. Speaker, I have long been addicted to scanning the so called comic strips that appear in our daily and Sunday papers. I have followed the careers of the characters, such as Uncle Walt and Skeezix, Little Orphan Annie, Sgt. Stony Craig, and others for many, many years. Among these characters the most interesting and exciting of them all are Terry and Flip Corkin. On yesterday, Sunday, October 17, Milton Caniff, the artist, presented one of the finest and most noble of sentiments in the lecture which he caused Col. Flip Corkin to deliver to the newly commissioned young flyer, Terry. It is deserving of immortality and in order that it shall not be lost completely, I present it wishing only that the splendid cartoons in color might also be reprinted here. The dialog follows:

“On April 3, 1989, on the first anniversary of Caniff’s death, the Air Force officially discharged Steve Canyon from the service and presented his United States Air Force discharge certificate, service record, flight record, personnel file, and this shadowbox featuring Canyon’s service medals to the Caniff Collection at The Ohio State University.”

Originally, before the Kirby /Marvel result, I had intended to offer this passage about “Terry and the Pirates” as evidence of the power of the sublime as a political tool and to discuss the slippery parameters of cultural institutions and government bodies. I wanted to interrogate how diction in comics elevates or otherwise shapes response and meaning. In the end, the colonization of the Colonel Corkin speech by a government representative suggests that elevated diction is recouped by the ruling class, even in the ambigous guise of applause. Rhetoric, especially sublime rhetoric is a commodity like any other; it is a currency in the capital of the state and its many means of self-reproduction. For the moment, the comic image is undergoing the same recoupment as its rhetorical counterpart. Its value and its final place in American ideology will continue to be down played until its full financial worth can be ascertained. The constantly evolving new medium of technology and the fiscal world of “not as yet ripe for deals to be sealed” offers a climate of uncertainty for those who would capitalize the image.

Kirby ‘s work cannot be valued: the market is not ready.

A pretty brilliant essay! There’s a great deal to digest, but — just to pick on one point — the examples of how Lee transformed Kirby’s blunt dialogue-directions into grandiose prose, “…amplified language and words that are of a suitable weight to match the visual narrative and content…This language is that of great men doing great things” are exceptionally telling. And serve to rescue Lee from accusations (which I’ve been guilty of as well) of simply adding slick verbal glitz.

In fairness to Kirby, though, his side-notations to Lee were deliberately spare, done knowing the latter would come along and pump them up. It’s not as if his own writing on titles he wholly controlled and wrote was as bluntly workmanlike.

Great stuff.

BTW (You probably knew this but…) Thor is an example of one of the characters that were actually first scripted (or had the scripting credited to) Stan’s brother Larry. (Ant-Man and Iron Man as well.) So…

Hey Marguerite. I like the juxtaposition of Lee/elevated language/upper class, and Kirby/plain language/working class. I’m a little unsure I buy the idea that this is something that can be generialized to the writer/artist relationship in comics generally.

Lee was pretty unique, I think, in being a writer/manager. There are maybe a couple of other instances I can think of (Marston was kind of like that, though to a lesser degree). But overall, it seems the more typical set up was that there was management, and then there’s the writers and artists, who are both treated like shit. Certainly, Alan Moore (probably the most influential/important mainstream comics writer of the last 30 years) has been treated more like Jack Kirby than like Stan Lee by the people he’s worked for. I know Bob Haney (a very popular writer) was treated like shit. And so forth.

I’m just not convinced that the Lee/Kirby relationship was paradigmatic in the way I think you’re saying it is….

Noah: “I’m just not convinced that the Lee/Kirby relationship was paradigmatic in the way I think you’re saying it is.”

Actually, I want to go deeper than the primary relationship between Kirby and Lee and I will certainly acknowledge exceptions. I’m speaking here of commercial comics primarily.

I suggest that the commercial writer is not stigmatized by his contact with (base) money, whereas the commercial artist is frequently seen as “low,” particularly in relation to fine artists. When successful, the fine artist stands to make far more money than the commercial artist, but the unsavory taint of “work-for-hire” does not cling to their imaginary persona and is largely ignored. It strikes me that the comic writer is not subject to epithets of “low” or “high” either, instead their creativity and storytelling ability is lauded and criticized as freely as is any other writer.

In order to escape this position the artist must become an “auteur,” artist-writer to be fully acknowledged as worthy.

There is a war of classes, in which verbal literacy reigns above visual literacy, unless the visual is safely put aside as “high” culture. Only the cultural elite can understand that stuff, right? If we as scholars do not recognize our own problem, which is to promote writing as superior because we are mostly writers and it is where our expertise lies, then studying the “genre” of comics is pre-redundant, because the pictures are only secondary illustrations. If we do not re-evauate the way that we understand this relationship of image and text to operate then we risk an opportunity to embrace a complex and extraordinarily social, collaborative, cultural production, an opportunity to find out something new.

Hmmm…I’m still not really convinced. Lee is not infrequently seen as a ridiculous hack, isn’t he? Does anyone really consider him a genius? Anybody who cares about comics as an artform (i.e., people who would be apportioning aesthetic status) rate Kirby and Ditko well above Lee as artists. I certainly do, and I don’t even like Kirby and Ditko all that much (I mean, I don’t hate Lee or anything, but he’s clearly not a great artist in any sense.) I think comic writers have often historically been considered hacks, anyway. (And many of them were in fact hacks, for that matter.)

Caro often makes just the opposite argument, doesn’t she? That is, that narrative complexity is neglected in comics, and the accolades tend to just go to visual artists who are talented.

Maybe it’s different groups? I think within comic fandom art tends, or has tended, to be considered more important than writing. It’s possible in academia that’s reversed? And certainly the new comics subculture (post comics journal victory) tends to see writer/artists as the real auteurs….

Maybe the article should have been about Alan Moore, and who ever the artist is for the scripts he writes.

Alan Moore didn’t get any half votes for his work in the poll, and Charles Schulz didn’t get two votes for writing and drawing Peanuts.

Well, the votes in the poll were for comics, not creators, so nobody got half votes.

Moore’s really careful to give equal credit/rights to the people he works with, or at least that’s been my impression.

It’s not Moore himself, but the common perception which diminishes the role of his co-creators. Isn’t Marguerite writing about something larger than one example; the perception of text as intellectual, and art as something more like figure skating?

Yes…I’m just questioning whether art is really perceived as figure skating in any kind of systematic way. Moore is definitely seen as the auteur behind the work he does; I think that’s fair to say (though I don’t know that Moore perceives it that way.) But if anyone is seen as a genius in the Lee/Kirby pairing, it’s sure not Lee, whatever the courts may have decided.

Moore does not see himself as the sole auteur of his work—unlike his critics, he understands how much his collaborators bring to the table. Gibbons is versed in cartooning. Everything in Watchmen is drawn with his comprehensively articulated three-dimensional visualization, his control of on-model characterization, his acting abilities.

What seems to be generally misunderstood or ignored is that in comics the story and art are united to a common purpose. To attribute the “story” in comics to the “writer” is erroneous. The story is not only in the text but is imbedded in the art as well. Both text and art are intrinsically woven to create one thing, the story.

If the text was the only valid creative aspect of comics, then our time might be better spent discussing purely textual forms of literature.

From TCJ 145, Eddie Campbell on Alan Moore and his own contribution to From Hell:

Are the working relationships between Moore and Gibbons, and Lee/Kirby at all similar? Aren’t there people who think Kirby plotted the Marvel comic book stories?

Was Chaplin the author his his silent films? If a Lee came along and over-dubbed dialog would Chaplin no longer the the author of City Lights, or would the film be compromised?

The question for critics of who deserves the most credit for the strength of a collaborative work is something that needs to be dealt with on a case-by-case basis. With the Lee-Kirby and Lee-Ditko work, Kirby and Ditko get most of the accolades because analysis of the material’s strengths and knowledge of how the work was created points critics in that direction. Barry Windsor-Smith and Neal Adams get most of the acclaim for their collaborations with people like Roy Thomas and Denny O’Neil for the same reason.

The same is true of Alan Moore. Analysis of the final work, his scripts, and the work of his collaborators with others points to his collaborators being creatively subordinate to him in pretty much every instance.

James,

Are the themes, characters, dialogue, etc. of Watchmen more like Moore’s other stories or Gibbons’? Moore is the principle auteur.

Didn’t see Robert’s post at the time. I obviously agree.

Anyway, I follow a few actors and cinematographers in films. The films diverge more in quality and subject matter than with a director or writer, but that doesn’t mean there’s not something unique and creative that these actors and cinematographers bring to each film in a pretty consistent manner.

Gibbons and Lloyd brought alot of ideas to the table in terms of the making of their worlds (just as two examples). It was Lloyd who wanted to abandon thought balloons as well, an aesthetic “breakthrough” in V for Vendetta. Some of the “plotting” was definitely done by the “artists”–and while Moore often/usually gives “breakdowns” for each page, this isn’t always the case (and artists have been known to deviate, certainly). Bissette and Totleben also provided many of the character and plot ideas for Swamp Thing (Constantine was a Bissette/Totleben idea—the whole Nukeface story arc was also, etc.)

I actually see Moore as a hinge where (for a time anyway) writers began to be seen as the auteur and the most important figures in collaborative mainstream comics. (Neil Gaiman, Grant Morrison being other examples who rode the Moore train—it helped if they were British). Before the mid-80’s most of the stars in the comics firmament were the artists (at least aesthetically—obviously Lee was popularly known…but he may well be the only well-known writer who was not also an artist). I think, really, it depends somewhat on where the innovation is coming from (or where it is perceived to come from). Moore’s impact and influence was so large that people couldn’t help but pay attention to him as a powerful force. The same can be said of Kirby. Both were screwed financially and in terms of creator’s rights…although Moore has done much better for himself financially. I see Moore’s greater financial success more as a shift in the comics landscape away from characters-as-commodities to creators-as-commodities…(although obviously characters remain commodified–and to a great degree in other media).

To say that people see Lee as some kind of aesthetic genius/force is false, obviously. People came to see him as the creator of these characters and this kind of comics storytelling basically through marketing…His own and Marvel’s. Every Marvel comic had the “Stan Lee Presents…” moniker and it was a conscious decision to make him “the face (and voice) of the company.” Anyone who knows the history knows that Kirby was at least an equal creative force (not to mention Ditko)–but to the broader public (to people who don’t even read comics…and never have), Stan Lee may well be the ONLY superhero comics figure they know of any kind. To even call him a “writer” is kind of charitable in most cases. He filled in balloons, but he did have some flair for doing so.

I don’t think this has much to do with the legal case. I agree with Marguerite that the Kirby estate tried to establish too much. Also, contract law is not about aesthetic “credit” as the decision says…it’s about what agreements were made. Kirby agreed to page rates standard to a exploitative industry (as did Alan Moore–though he did get some percentage of profits), and that’s where the decision comes from. Probably, it’s legally correct, even if it is an ethical abomination. I’m not a lawyer, though…so maybe there are other avenues to pursue here.

Charles’ question is a little disingenuous. You could equally well ask “Is the visual depiction of characters, page breakdowns, and backgrounds, more like Moore’s other works, or Gibbons’?” You’ll obviously get a different answer.

I wonder, for most superhero comics buyers, if people buy more for the art or for the “story.” I’m guessing more people buy for “stories about their favorite characters” more than for “drawings of their favorite characters.”—That’s just a guess, though…I know there are definitely people who buy principally for the art. I’m curious as to the numbers, though.

Ideas are a dime a dozen; it’s what you do with them that’s important. John Constantine is a very good example of what Moore does with his collaborators’ ideas. Constantine came about because Bissette and Totleben wanted a character in Swamp Thing who looked like Sting. That was the whole of their idea. That’s what they brought to the table. Moore came up with everything else about the character. Would I say Moore deserves the most credit for Constantine of the three? Definitely.

Eric–

You also might want to compare Gibbons’ work in Watchmen with Bolland’s in The Killing Joke. Beyond the rendering styles and the hyperbolic treatment of The Killing Joke‘s climactic fight, the visual thinking in both is largely the same.

I can’t comment about Morrison’s scripts–I haven’t seen them–but I have seen some of Gaiman’s. Moore dominates his collaborators to a much larger degree.

Eric: “I wonder, for most superhero comics buyers, if people buy more for the art or for the “story.” I’m guessing more people buy for “stories about their favorite characters” more than for “drawings of their favorite characters.”—That’s just a guess, though…I know there are definitely people who buy principally for the art. I’m curious as to the numbers, though.”

I absolutely buy for the art. I would say that most of us who were initially attracted to manga loved the way it looked and that opened the door for further interest. It has always been the art for me ever since I was a kid. I used to scour the few American imports in England for Kirby, not for the stories. his images were exciting.

I think that one of the aspects that went un-discussed on the top ten list was the way color and art changed the face of comics. Lyn Varley’s contribution to “Ronin” made me grab it and it remains a strong favorite. I loved the fresh look of the book. Around that time, Bill Sienkiewicz brought “Electra Assassin” to life with his innovative paint and montage. That effort really made my heart beat faster. A year or so before Gary Panter gave us “Jimbo’ with its fantastically unorthodox production values and had let me dream that we were entering a whole new period of opportunity and ideas.

Sorry, It’s Lynn Varley. I apologize for missspelling her name. goodness knows she deserves better!

I tended to buy for story when I was reading Alan Moore…but I always got the impression that that was a little unusual among fans.

…At the last comics store I frequented while living in Miami, I was known as “the guy who likes Alan Moore”!

But since Moore’s appearance, I think there are lots of “guys who like Alan Moore” (and to a lesser extent some of his followers…) I am, in fact, one of them…and I’ll read (and have read) virtually everything he’s written (even the questionable stuff), regardless of the artist… I still think it’s a mistake to not give the artists their due.

Btw, I know that Bissette/Totleben’s main contribution was to Constantine’s appearance…and I agree that Moore deserves the lion’s share of the credit for most of his successes (including Constantine).

Nevertheless, I think our tendency as a culture/society is to choose one “genius” and give all credit and accolades to him/her. Moore’s comics work is, for the most part, collaborative…and his collaborators do deserve credit for their part in the finished product. Moore was blessed with (and often chose) really good collaborators…and his scripts tended to bring out their best work. However…they did DO that “best work”–they did contribute to the storytelling, and they too deserve credit.

If ideas were really “a dime a dozen,” you’d see greater amount of decent ones, frankly.

I think Eric is right that there is a tendency to single out one “genius” figure as the one who gets credit for a collaborative work. We need a name for this tendency — perhaps credit auterism. I myself think that the best comics are the ones done by a single writer/artist, but there have been important collaborations which in two or more parties are essential to the end product — I’m thinking here of the various Pekar collaborations with Crumb and others, of the Eisner studio which created The Spirit, of the Stanley/Tripp work on Little Lulu, and the various assistants used by Frank King and others.

One nice thing about the recent wave of comics reprints is the increasing attention given to ghosts, assistants and editors. In recent books reprinting strips by Alex Raymond, George Mcmanus, Roy Crane and others, we’re getting information on the uncredited people who were instrumental in creating the work.

Charles Hatfield’s forthcoming book on Kirby also raises the collaborative issue, noting correctly that aside from writers like Lee, Kirby also worked with a host of other collaborators (inkers, letterers, colorists). This collaborative dimension needs to be dealt with forthrightly, rather than falling back on a lazy credit auterism.

Well, I don’t know that it’s lazy exactly…there are different kinds of collaboration, and certainly in some cases it’s more clear than others that one person or another seems to be more or less in the driver’s seat. As Robert pointed out, Eddie Campbell was happy enough to see himself as a craftsman realizing what was essentially someone else’s vision. Of course, who realizes that vision, and how, is still important…but I don’t think it’s lazy or even wrong to say that Alan Moore is the auteur on most of his projects. Similarly, Marston actually hired Peter himself, so it makes sense to see Marston as the primary auteur…though I think Peter is a genius, and WW clearly would not be the same achievement without him.

The relationship of Kirby and Stan Lee is obviously quite different…and the relationship of manga artists to their assistants is different again. It’s certainly worthwhile to make those points…though again, I don’t think it’s wrong to note that sometimes the vision is more one person than another’s (whether that one person is the writer or the artist.)

…And some of Moore’s art collaborators contributed significant ideas as well; for instance, David Lloyd suggested the Guy Fawkes mask for the visage of “V”…

BTW, ran across the fascinating article, “Alan Moore and the Graphic Novel: Confronting the fourth Dimension,” worth checking out: http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v1_2/carter/ .

It should be pointed out that the specificity of Alan Moore and Harvey Kurtzman, and the Marvel Method where the “writer” acts as what in a film would be a script re-writer, a refiner who reconfigures and/or adds a layer of gloss, are very atypical practices. I’m unsure if anyone works Marvel Method anymore…I believe most collaborative artists work from “full” scripts.

If one takes the film analogy further though…hard to think of a film where the writer gets the major applause. In comics the artist approximates the functions of the entire film company, director, actors, costume, set, etc etc, everything, in other words, but the script.

But comics are not film, and we want comics to be well written.

So I do not underestimate the value of the writer, as some seem to want so badly to do to the artists.

Some of the text-centric credit auteurism that has been rearing its head seems to come from either ignorance of, or willful disregard of, visual artistic process. As if the artists use a form of magic to make the drawings appear on the page, or that it comes so easily to them that it could hardly be called creative.

Charles’ question is a little disingenuous. You could equally well ask “Is the visual depiction of characters, page breakdowns, and backgrounds, more like Moore’s other works, or Gibbons’?” You’ll obviously get a different answer.

Is the visual depiction of the characters or the backgrounds really the most crucial aspects of the Watchmen? These are questions you could ask of any illustrative work that accompanies verbal text, right? As for the structure and order of panels, is there anything as complex in Gibbons’ other work, such as his and Miller’s Give Me Liberty? What about J.R. Williams on Promethea? If the art is 50/50 with the writing in terms of the storytelling, then Moore really defies the odds in terms of consistency relative to his artists.

James,

In films, the director often manipulates the script a great deal. But if you look at True Romance, for example, does it come closer to being a Scott film or a Tarantino film? With the exception of a changed ending, Scott stuck pretty close to what Tarantino wrote. It looks like a Scott film and the music isn’t what Tarantino would’ve chosen, but it still feels pretty much like a Tarantino film. Oliver Stone, however, completely manipulated his script for Natural Born Killers, and it feels much more like a Stone film in just about every way.

I think True Romance kind of ruins Tarantino’s script, actually. Movie directors have a lot of power.

Charles: “Is the visual depiction of the characters or the backgrounds really the most crucial aspects of the Watchmen?”

I don’t know about _Watchmen_ but if you want to see the background telling the whole story go here (to minute 7.30): http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dMbcJD_Girc&NR=1 It’s the marvelous Lubitsch touch. We credit it to him, not to the set dresser, of course.

Mike wrote: “…And some of Moore’s art collaborators contributed significant ideas as well; for instance, David Lloyd suggested the Guy Fawkes mask for the visage of “V”…”

And how do we know this? Through some interview anecdote, no doubt. But that’s the problem with collaborations, especially those that took place in the 1970s and earlier — no one really knows who did what.

Unlike today, where recorded interveiws or panel discussions are everywhere and almost every aspect of a new project is endlessly parsed on blogs, older creations were developed out of the public eye. In fact, because so little was recorded during the 1970s and earlier, some creators of key characters — in a he said/she said sort of way — adamantly dispute who created what back in the day.

So here folks like us are, 40 years or more later, trying to put the few puzzle pieces we have together to try and figure out the truth.

And just to show how hard the process can be, look at this splash page I drew in 1975 and tell me, based on the credits and available information, who created what (no cheating if you saw my image post of this a few years ago).

http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/Weightmaster-72dpi.jpg

The truth may not matter for something like the above, but for concepts that may be worth millions of dollars, the stakes about “who created what” are far higher.

———————–

Robert Stanley Martin says:

…You also might want to compare Gibbons’ work in Watchmen with Bolland’s in The Killing Joke. Beyond the rendering styles and the hyperbolic treatment of The Killing Joke‘s climactic fight, the visual thinking in both is largely the same.

————————

For those who missed it when first mentioned at HU, in the July 27-26 posts at http://eddiecampbell.blogspot.com/ , Campbell mentions “I didn’t know Alan drew thumbnails for all the From Hell chapters, believe it or not…Remember, I never saw these thumbnails; they were just Alan’s way of keeping track of all the movements.”

What’s fascinating is how, though Campbell changes some angles, the narrative rhythm feels the same. That’s how highly visually-specific Moore’s scripts are.

————————-

I can’t comment about Morrison’s scripts–I haven’t seen them–but I have seen some of Gaiman’s. Moore dominates his collaborators to a much larger degree.

————————-

When I saw an issue of a comic book writer magazine advertising on the cover it was featuring a Grant Morrison script, I rushed to open it; Morrison is one of my favorite comics writers. Alas, I was dismayed to find there was hardly anything to it! Barely-there directions…

Morrison’s writing discussed at http://www.barbelith.com/topic/25013 (with some Morrison thumbnails); with a link to Morrison’s “X-Men” #121 script, which at least has far more “meat” to it: http://web.archive.org/web/20020203131947/www.marvel.com/comics/nuffsaid/xmen121/page1.htm

————————–

James says:

…Some of the text-centric credit auteurism that has been rearing its head seems to come from either ignorance of, or willful disregard of, visual artistic process. As if the artists use a form of magic to make the drawings appear on the page, or that it comes so easily to them that it could hardly be called creative…

—————————–

…And to that add the wish for publishers or movie studios to focus publicity on a single “star” creator. Who, if they’ve had a batch of successes with an assortment of collaborators, would be the “common factor” in those hits…

Pingback: Here’s a brutally realistic thought about comics: | Allan Haverholm

Pingback: Stan Lee Presented (Part 3) | Sequart Research & Literacy Organization

Pingback: Here’s a brutally realistic thought about comics: | Allan Haverholm

Pingback: Here’s a brutally realistic thought about comics: – Uncomics