Click on images to enlarge.

_________________________________________

“The impacts of both pictures and words drive more deeply into human awareness than any anthropologist has yet cared to note.”

-Milton Caniff

_________________________________________

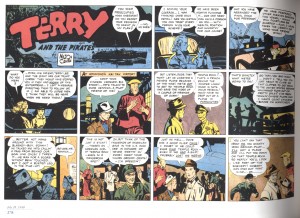

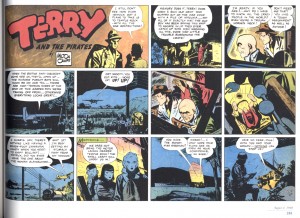

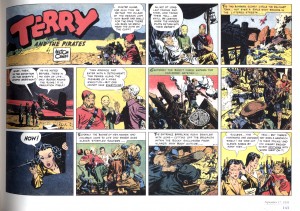

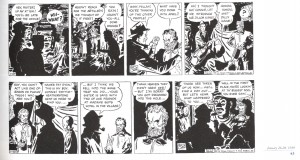

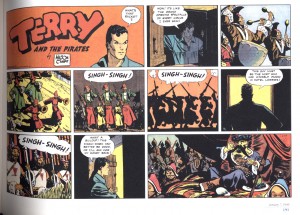

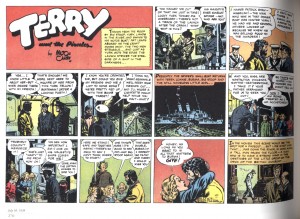

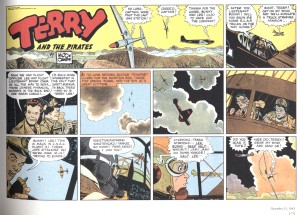

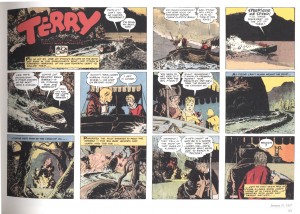

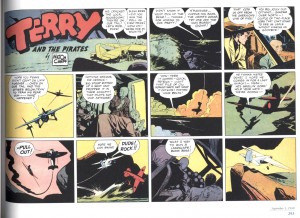

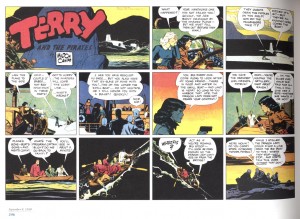

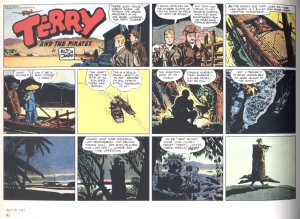

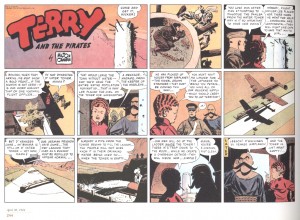

I just read four of IDW’s collections of Terry and the Pirates back-to-back. They comprise one of the most gripping narratives I have seen in comics. They are essential reading for anyone who loves the medium of cartooning and enjoys exciting, involving storytelling. These gorgeous, thick hardcover volumes edited by Dean Mullaney each print two years worth of black and white daily strips and color Sunday pages. The stories certainly read differently in book form than they could have with the protracted exposure of serial doses. Once I was hooked at the outset, I had a hard time putting down any given volume. The relentlessly powerful engine that Caniff stokes pulls the reader along helplessly.

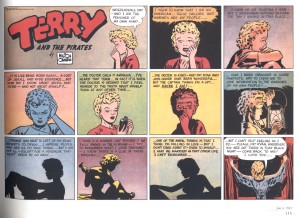

A lot of what Caniff accomplishes here has not been surpassed in comics. Many of the characters resonate strongly with the reader. Throughout, the sensitive handling of Terry’s “coming of age” is impressive. So is the villainy of a host of despicable scoundrels, some of them quite believable as is the case with the wretched Tony Sandhurst. I cared about what happened to Burma, Raven Sherman and Rouge; in this Caniff’s nearest correspondent is Jaime Hernandez. Their characters’ appeal is not only due to their motivation and dialogue but also to the way that the artists are able to put forth their nuance of expression and gesture. Like actors, cartoonists such as Hernandez and Caniff must believe their characters to be able to convey credibility to the reader.

The books boast excellent reproduction and fascinating supplemental essays by Bruce Canwell, Jeet Heer, Russ Maheras and others, Terry-related promotional art and photographs of the artist and his circle. There’s only one down note, in his introduction to Terry V. #2, Pete Hamill repeats a claim that he made in a letter to The Comics Journal (#135, 1990, p.34) years ago, that the millions of people who read the strip did so for the writing rather than the art, citing that because Caniff’s friend Noel Sickles’ strip Scorchy Smith was beautifully drawn but dead in the water story-wise, ergo the story (“that is, the writing”) is what is primarily significant. Hamill seperates the art from story as if the story lies only in the text. Yes, Caniff is a good writer, and yes, there is almost nothing that I can compare to this in scale and quality, but the fact is that the narrative in comics is carried by both text and art. Caniff is one of the greatest exemplars of this.

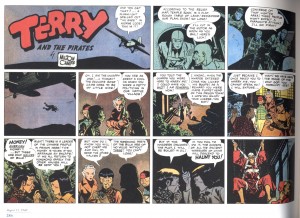

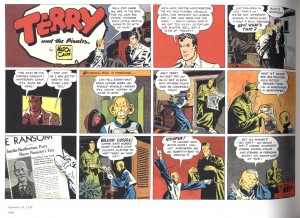

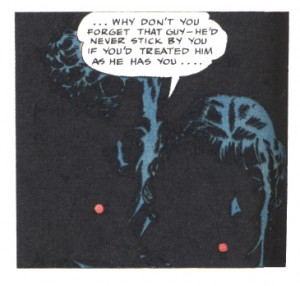

Sickles WAS missing part of the equation—both text and art signify to the reader, both are “read.” Caniff was prodigiously talented at both and it is their interlocking orchestration that marks his mastery. The story would not have had anywhere near the same impact and import to his huge audience if it had been drawn by another artist, if it had been done without Caniff’s sometimes oddly stiff but still expressive figuration and clearly differentiated likenesses, his sense of deep space, composition and dramatic lighting, his facility for exacting observation and reference, his pen and brushwork, his color, the level of developing skill involved in his amazingly nuanced renderings of his characters and their world.

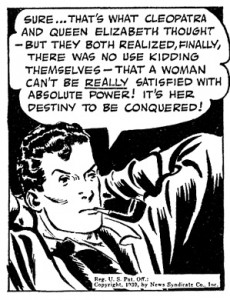

The powerful impact of imagery in Caniff’s work is made clear, though unfortunately in a negative way, by the fact that the work is so tainted by racist depictions. Connie is no more forgivable than is Will Eisner’s Ebony. These characters permeate and compromise the works of their respective creators. To forestall apologism, I do not believe Caniff and Eisner were forced to include these depictions. Both also tended to draw non-racist ethnic characters next to absurdly caricatured ones—as in Eisner where one sees Ebony attempting to woo a more realistically cartooned African-American girl, in Caniff one sees racist depictions of Japanese people and the Chinese Connie interacting with more realistically-rendered images of Chinese people. Connie is omnipresent in Terry and often displays ingenuity and courage, but his visual depiction is irrevocably abhorrent, even if one could find a way to tolerate the obvious glee Caniff invests in the character’s mangling of English.

Still, if one can somehow ignore this mitigating factor, there is much of great value to be found in Terry and the Pirates. At this moment, the work in Volumes 2, 3 and 4 resonates most strongly to me. I have yet to read the final volume, but so far I prefer the stories done before Caniff became more intrinsic to the American war effort. The later stories, as well as those in Caniff’s subsequent strip Steve Canyon have a feel of military formalism that seems a bit less free and alive than the more imaginative earlier adventures. But when it is Pat, Terry, Connie and Big Stoop blasting through stories that are driven by the artist’s superlatively developed female characters such as Burma, April Kane and the Dragon Lady—this is the stuff of great comics.

I scanned pages from several of the volumes to post here, which represent moments that struck me as particularly well-articulated, amazingly drawn or fabulously colored, or that showed places in Caniff’s trajectory that I feel had to have been seen and loved by certain artists, who I may or may not have known were profoundly influenced by Caniff.

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

________________________________________

_________________________________________

________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

_________________________________________

I agree that Caniff is everything that you say he is and more… but… we must have a very different idea of what a great writer is. These are just manichaean adventure stories for children. Even so I see a few great moments (being the one in the Smithsonian book one of the best…), but no consistently great writing… I even doubt that the format and commercial purpose of the newspaper comic strip allowed great art to happen…

Domingos, I mean that in a relative sense…great writing comparatively speaking in the context of comics. Not a lot of even competent work to compare it to even now. In Caniff’s time there was almost nothing.

I should further qualify that I have little sense of how the strip would have been percieved in dribs and drabs over twelve years. It depended on the papers one had access to—the Sundays read one way, the dailies another. Someone would have to have clipped and collected all of them to read continuously, to get the effect produced by these books. As they are, they read very well indeed.

I especially like Caniff’s women characters. I mean Burma, who is a version of a fallen woman with a heart of gold (Caniff owes a lot to the Hollywood films of his time; Marlene Dietrich comes to mind), but also Raven Sherman or Hu Shee.

Hamill seperates the art from story as if the story lies only in the text.

When Hamill or others (including myself) refer to the “writing” in a comic, we’re not referring to the text so much as we’re referring to the narrative conceptualization and execution (as reflected in the ideation, emphases, and pacing) of the material. The reference to Sickles highlights that draftsmanship and rendering ability for its own sake doesn’t count for a lot. Those skills are necessary, but once beyond a certain level of competence they’re not going to make or break the material.

A figure like Dave Gibbons illustrates this very well. In terms of panel composition, draftsmanship, and rendering, I don’t think his work on Watchmen is markedly superior to his work on Doctor Who, Green Lantern, or Martha Washington. But Watchmen is a vastly superior comic, because the underlying thinking (the “writing”) is so much stronger. The architect gets the bulk of the credit for the building, not the carpenter. That’s why Alan Moore gets far more acclaim for Watchmen than Dave Gibbons.

That’s also why Caniff the “writer” deserves more credit than Caniff the “illustrator” for the strength of his work on Terry and the Pirates. Additionally, it’s why Caniff deserves the blame for the mediocrity of Steve Canyon for most of its run, as opposed to Dick Rockwell, who drew the bulk of it.

RSM wrote: “Additionally, it’s why Caniff deserves the blame for the mediocrity of Steve Canyon for most of its run, as opposed to Dick Rockwell, who drew the bulk of it.”

Perhaps you should clarify what you mean by the saying that “Steve Canyon” was mediocre for “most of its run.”

I say this because I’d argue that the strip was excellent, and at times exceptional (as good as some of Caniff’s best work on “Terry”), from 1947 until at least about 1960. I can’t be more definitive about the transition because there are huge chunks of “Canyon” strips from the 1960s and 1970s I simply haven’t read.

But even if those first 13 years of “Canyon” were it (five of which were non-Rockwell), that still eclipses Caniff’s 12-year stint on “Terry.”

Food for thought…

I tend to be more focused on story than art…though James has gotten me thinking more over the last months about the ways that the art is integral to the story.

Alan Moore’s sort of an outlier example, because his scripts are so detailed. As a contrast, here’s an example where I know the artist had very little visual direction. As a result, the artist very much controlled the narrative flow (or lack thereof), even though much of the “plot” (such as it is) came from the writer.

It seems like between those extremes you’ve got a wide range of collaborative possibilities — and if the creator is doing art and writing herself, as Caniff is, it seems almost pointless to separate the duties. For instance, in the 9/17 page (one of the first James reprints), there’s a silent panel showing the soldiers marching past dead bodies. Is that panel “written” by Caniff? In what sense? It’s his art that creates/drives the narrative there. Similarly, in the first sequence James shows, there’s that panel where the characters are staring out the window; their dialogue wouldn’t really make sense if you couldn’t see what they were doing. If you wanted to, you could say, “well, positioning them there at the window is the writing, and then the actual rendering is the illustration” — but does making that kind of distinction really make any sense?

Or…I don’t know. Take one of the Peanuts strips where Snoopy and Linus are chasing each other around trying to get hold of Linus’ blanket. The “story” in those strips is generally supplied primarily by motion lines rather than dialogue. Does it make sense to credit Schulz “the writer” with that?

It just seems like thinking about these things on a case by case basis is maybe more useful than laying down firm universal rules, whether those be, “writers are responsible for the success or failure of a comic,” or “artists are as important to narrative as writers are.” I think it really depends on the individual piece in question. In the case of Terry and the Pirates, which relies for its effectiveness so heavily on both Caniff’s writing and illustration skills, I guess I’d tend to agree with James that it’s maybe more useful to think about how those two interact than to try to separate out one and assign it primacy of place.

Steve Bissette’s got a long post about the contributions of artists here, incidentally.

Noah–

I defined the writing for the sake of my argument (and I believe Hamill’s) as “the narrative conceptualization and execution (as reflected in the ideation, emphases, and pacing) of the material.” That covers pretty much everything you’ve brought up.

Can illustrators transform a writer’s material and make it their own? Of course. Look at Sienkiewicz’s work with Frank Miller on Elektra: Assassin or Daredevil: Love and War. Those books would likely bear little resemblance to what was published if Miller had been working with another artist. The same can’t be said for Gibbons; I don’t think Watchmen would have been substantially different if Brian Bolland, George Pérez, or Steve Rude had drawn it instead. The same is true with Sickles and Caniff; Hamill specifically pointed to Sickles and Scorchy Smith to make his point because Caniff and Sickles had virtually identical art styles. Sickles even drew a number of Terry strips early in Caniff’s tenure, and you have to have a really good eye to tell which feature his art and which feature Caniff’s.

I read the Bissette piece over the weekend. No one’s denying the investment of time and labor is far greater for the artist than the writer. Carpenters put in a lot more work on a building than the architect does, too.

“I defined the writing for the sake of my argument (and I believe Hamill’s) as “the narrative conceptualization and execution (as reflected in the ideation, emphases, and pacing) of the material.” That covers pretty much everything you’ve brought up.”

But it’s not the case that that all is done by the writer in every instance. And in the case where the artist and writer are the same person, what does it even mean to separate out what is done by the “writer” and the “artist”?

“Can illustrators transform a writer’s material and make it their own?”

I just wanted to respond to this from my experience….to say that Bert made my writing his own in the creation of our collaborative comic doesn’t really get at what happened. There was no “my own” until Bert did the art. I mean, there was the script, which is kind of fun on its own I suppose, but it was always imagined as a comic, and Bert had this insane idea for how to put it together (as one gigantic wall poster, basically) which I never would have come up with and which I found kind of terrifying when he broached it. it really was a collaboration; saying he was building a house on my instructions is really misleading since; I didn’t have any idea what the house would look like till he built it.

As I said, I think our collaboration was an extreme example..but maybe useful in showing how variable the collaborative process can be.

Noah wrote: “As I said, I think our collaboration was an extreme example..but maybe useful in showing how variable the collaborative process can be.”

You are absolutely right. All collaborations must be examined on a case-by-case basis.

For example, if a character is well established (Tarzan, the Lone Ranger, the Shadow, etc.), and an artist is given a full script to follow, that artist’s impact could very well be minimal and totally interchangeable. That said, in some cases, the artist’s art and layouts may be so transformational he/she trumps the writing. Berni(e) Wrightson and Michael Wm Kaluta did this with DC’s Shadow during the 1970s.

However, in the case of “The Marvel Method,” where artists like Jack Kirby or Steve Ditko were given little, if any, plot direction and no script, it was the writer who very well could be interchangeable. In addition, if a character is new when the Marvel Method is used, the artist may play the biggest role of all in creating the iconic visual look of the main and supporting characters/villains.

Harvey Kurtzman, who was both a writer and an artist, and who often provided layouts to go with a completed script, added a different wrinkle to “who contributed what” to the finished product. But even then, if one looks at, say, “Mad,” the artist still could shine through, as did Bill Elder or Wally Wood; flop, as did Bernie Krigstein; or have mixed results, as did John Severin.

James — If one examines the “Terry” daily strips from the 1938-39 time frame, there are a number of inking techniques Caniff uses seem to have been later adopted by Wally Wood. Wood was in his formative drawing years during this period, so it would not surprise me at all if Wood was heavily influenced by Caniff’s inking.

I think this would be a good essay on its own.

Russ: what I tried to show with all those scans was pages that I felt almost certain had to have been seen by various artists.

But there were surprises, since before reading these books I was literally unfamiliar with Caniff…for instance I had no idea how influenced by Caniff Johnny Craig was. It seems clear now. There is a few months that have an odd heavy brush inking that screams Robbins and Don Heck. The set where I showed 5 in a row (minus one spoiler) is just exquisite, I see people like Bernie Wrightson and Mike Kaluta in there.

And BTW I put pages in that I thought were drawn by Sickles, who didn’t have the knack for character and storytelling that Caniff did but whose observational skills were more acute, whose draftsmanship and atmospherics are more realistic—as in the water paths of the boats in the one and the compositions w/ hair and light within mosquito nets in the other.

BTW 2: I don’t mean to dismiss the more military phases of the strip…they are impressively researched and work just fine but by their nature they become a more disciplined scenario and they are also heavily encoded with military jargon, which just makes for a little slower going than the more freewheeling earlier years.

James — Yeah, Jeet Heer once complained about the heavy use of military jargon in “Steve Canyon.” And while I can empathize with his observation, I pointed out that Caniff’s 1940s-1950s audience was far more military savvy than audiences today.

First of all, the primary breadwinners (and thus, newspaper purchasers) during that era were men. There were something like 16 million people in uniform during WW II (mostly men), and the home front was bombarded (no pun intended) with military-heavy popular culture, news stories, newsreels, and letters from those 16 million military members. A WW II veteran I talked to once pulled out a box he still had full of more than a hundred letters he’d sent his family while he was in the service, and those letters were chock full of military jargon. In addition to the WW II veterans, millions more men in their 50s and 60s were veterans of WW I during that era.

The population of the U.S. was only about 130 million during the 1940s, so the number of veterans serving from WW I through WW II was probably more than 15 percent of the total population, and perhaps as much as 30 percent of the WORKING population. And the number of people who had relatives who were veterans of either war (or the two decades between the wars) was probably in the 90-95 percent range.

So Caniff was really just writing to his 1940s audience.

I can guarantee you that Hugo Pratt was hugely influenced by Caniff. He even swiped Terry’s last page in _Ann of the Jungle_.

Pratt was one of the most brilliant of Caniff’s students, for sure. Perhaps he surpassed the master, except in the area of color?

Pratt never did any colors in comics (he did great b & w washes though), but he was a brilliant colorist in his illos.

I have a nice book of Pratt’s watercolor drawings of women. Thanks for distinguishing between comics and illustrations.

Great Caniff article and scans, James!

(Gad, that “Connie at his worst” was mind-bogglingly grotesque; at least Ebony White fit in visually far better amongst the more caricatured characters in “The Spirit”…)

Was curious about Pratt’s watercolors; did some searching and found this, heavy on the iverbiage, light on the imagery:

http://fic123berichtvandedag.blogspot.com/2011/03/pinacotheque-de-paris-presents.html

Ah! That’s more like it:

http://spaceintext.wordpress.com/2011/04/19/watercolours-hugo-pratt/

Thanks, Mike. I’d like to see the wash stories that Domingos refers to. Hard to place Pratt because I see his work as great art/literature, as opposed to most other comics. I only have a few Corto Maltese books, but they form a sort of pinnacle of their own.

The washes that I talk about were done in Argentina (Pratt lived there from 1949 to 1962 or so…). I mean _Ticonderoga_: http://tinyurl.com/6b9zr9r

There’s some discussion because no one knows who really did these washes: Pratt or Gisela Dester. Some who know more than me about these matters say that Pratt did the washes on the characters and Gisela did the washes on the backgrounds.

Pratt is a good writer because he learned from the absolute best writer in comics, ever: Héctor Germán Oesterheld (the writer of _Ticonderoga_).

There are also washes in _Ernie Pike_ (dropped in the European reprints, I think).

Washes in _Ernie Pike_ (one of the best comics stories ever created): http://tinyurl.com/5v4mpmu

Thanks for the link; it is indeed an excellent story! (Good thing I know Spanish…)

Nothing like having a real-life event — defying the stereotyping simplifications of genre — to provide material.

(Though I’d wish the WAC’s face had been more expressive…)

Pike mentions her sad eyes. I think that Pratt depicts her perfectly: elegant, with measured gestures, quiet, keeping her war traumas to herself (marvelous underacting: look at her subtle smile at the beginning)). No one could beat Pratt in the depiction of women. His womanizing served him well…

Thanks for the links, Domingos! Wish I could read the strips. I recall reading somewhere that Oesterheld was murdered by the Argentine government, thrown to his death from a helicopter. Wiki doesn’t seem sure:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%C3%A9ctor_Germ%C3%A1n_Oesterheld

No one knows what happened to Oesterheld. The last time that he was seen he was a prisoner in Vesubio, a clandestine detention center. The person who saw him there said that he had been tortured and was in pretty bad shape. The guards let them talk for about five minutes and Oesterheld, saying that he was the oldest in there, wanted to shake everybody’s hands to say goodbye to them all. By then his four daughters (and two sons-in-law) were already assassinated (two grandsons were adopted and no one knows where they are).

That early work by Pratt looks amazingly similar to the work Jesse Marsh was doing for Dell in the 50’s.

I finally read _Ann of the Jungle_ because of this thread. It reminded me of how bad a writer Hugo Pratt was. He had the best teacher, but he was an awful student.

Domingos:

“Pratt is a good writer because he learned from the absolute best writer in comics, ever: Héctor Germán Oesterheld”

and

“It reminded me of how bad a writer Hugo Pratt was. He had the best teacher, but he was an awful student.”

So, which is he, good or bad? To my knowledge there are no translations of Oesterheld available in English so I can’t address him, but I’ll take the Pratt books I have over Caniff in terms of “writing”—the Cortos are beautiful.

I’ve been reading the Corto books from the beginning (in French editions), and while I love Pratt’s graphic style (way more than Caniff), the storytelling (in both the writing sense and the panel-to-panel sense) is not very good early on. I think Pratt gets better as he goes on though, as I feel like the later ones I have already read were better than the early one’s I’ve just finished, but we’ll see… I recall enjoying the Siberia one.

_Ann of the Jungle_ was Pratt’s first attempt at both writing and drawing and it is terrible. The Corto’s aren’t writing masterpieces either, but he got better over the years.

Rest assured though that Hugo Pratt never did anything remotely as good as _Ernie Pike_.

By the way Corto’s name comes from Oesterheld’s character Corto in _Sgt. Kirk_.

I have at least five disappointments in comics:

1 – _Matt Marriott_ will never be reprinted;

2 – Chago Armada’s complete work (especially _Sa-lo-món_) will never be reprinted;

3 – _Randall_ will never be reprinted;

4 – _Black Poppy_ will never be reprinted;

5 – _Ernie Pike_ (and I mean the more than 200 stories, not just the 30 or so that Hugo Pratt drew) will never be reprinted.

This means that three out of five of my disappointments are Oesterheld related.

Domingos, no art is dead unless no copies exist. One could take a cue from the late, sorely missed Dylan Williams, who made it his business to circulate work that he loved, sans authorization. I have packages Dylan made for me of the work of Noel Sickles (many years before the book came out, copies of Toth’s copies I believe, which were the only way a lot of people saw Sickles), Mort Meskin, Jerry Grandenetti and more.

If one has copies of the Oesterheld stories, one could perhaps collect and print copies them in some form or even translate them…or otherwise take more of a proactive role in ensuring that the work is seen by more people, to interest a serious publisher in putting the work out again, as has happened with some of the artists that Dylan championed. Not to dump it on your lap, but such an engagement with material you are obviously passionate about might resolve your disappointment. Or, just write about it more on this site and give us some examples…promote it.

Well, let’s see:

Matt Marriott:

The production values are so-so to quite poor, but the ADCCC (the All Devon Comics Collectors Club) reprinted some stories. Unfortunately these are all from the first decade. The series got better during the seventies in my opinion. Even so it’s better than nothing (thanks Dave!). A lot of the original art survived, but I don’t know where it is (besides owning some myself). Doug Beekman wants to create a site dedicated to Marriott, but he hasn’t done so yet… All the stories can be seen in microfilms in the British Library. David Lloyd proposed a reprint to Titan Books, but they said that it is poison. That’s all I know…

Chago Armada:

No reprints, but a few dozens in _Signos_ magazine # 21 (1978). I’ve never been to Cuba, so I know nothing about the possibility of a reprint. I wrote a letter (the old fashioned way, by snail mail) to Caridad Blanco, but I received no answer…

Randall:

I scanned it all, but no one knows who the Arturo del Castillo heirs are. This is the project that frustrates me the most because it would be done by my good friend and boutique publisher Manuel Caldas: http://www.manuelcaldas.com/ The art needs restoration. I’m sure that Caldas would have done a beautiful job… Now I’m waiting for 2040…

Black Poppy:

I read some stories (I own 300 or so of Oesterheld’s original comic books – 1957 – 1963), but not all, so I can’t even scan the whole thing.

Ernie Pike: ditto. Since Hugo Pratt is such a huge star in Europe the stories that he drew were published by Casterman (with color added! Bleagh! One of the stories was written by Jorge Oesterheld, Héctor’s brother, not by Héctor himself – European editions should acknowledge this, but they do their usual disrespectful and shoddy work).

I forgot Yoshiharu Tsuge. Why someone doesn’t publish his whole oeuvre in the West is beyond me.

Of course it is too bad about lack of originals and there’s not much you can do to get around too-dark coloring—-but printed magazines could be scanned and enhanced or corrected. If Oesterheld’s work is as strong as it seems it is then I’d love to see this stuff, but I’d need it translated, and that is a challenge of itself.

I’d like to know what Domingos thinks of the various Spanish artists who had work published in the 70’s Warren magazines.

Jose Bea was the best of the lot by a good sized margin. Of course the stories were all nothing more than “stuff.”

Not my area of expertize, I’m afraid. I remember reading something about them in the fanzine _Bang!_, but that’s all.

Elsa Oesterheld and, perhaps, a few of his friends (Jorge Luis Borges was among them) asked Oesterheld why didn’t he try to be a serious writer instead of a comics writer. He said that millions read his work, far more people than Borges’ reading public (that was reward enough for him). Oesterheld came from a German tradition of didacticism. He had a mission to accomplish: to pass humanist values to children. That’s why his writing is not difficult to read and far from difficult to translate.

I wonder if anything by him has been translated into English. there’s a mythical reprint of _El Eternauta_ in the UK, but I think that it’s just that: mythical, it never happened…

Pingback: El Realismo Degradado – Tradiciones Narrativas del Comic (I) | Nueve Párrafos

Pingback: Ton?i Zonji?: The Total Approach | James Romberger

Pingback: Caniff: Momentum | James Romberger