Netflix streaming allows for an eclectic diet of movies. You can view not just Hollywood crap, but crap from all over the world. Recently, I’ve been watching Italian gialli films from the 1970s. Giallo (meaning “yellow,” a reference to the genre’s origins in a series of paperbacks with yellow covers) is a sub-genre of the crime thriller notable for its exceptional levels of violence. A giallo plot is typically a murder mystery with a few red herrings, gratuitous sex, and a chase sequence or two. In other words, hardly different than the pulp crime novels familiar to most Americans. But the lasting impressions of these films has less to do with the “whodunnit” plot mechanics than with the gore. Murder sequences are often long, bloody, and elaborate.

Of the four gialli that I watched, Profundo Rosso (Deep Red) was far and away the best. I’ll discuss it in my next post, but for now I’ll focus on three other films: The Black Belly of the Tarantula, Don’t Torture a Duckling, and Who Saw Her Die? Normally I’d give a spoiler warning, but these films are from the 70s, so deal with it.

.

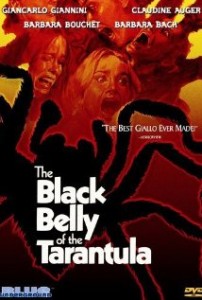

The Black Belly of the Tarantula (1971)

Directed by Paolo Cavara

Starring Giancarlo Giannini, Ezio Marano, Barbara Bouchet, and Barbara Bach

Genre entertainment can be roughly grouped into three categories: works that fail to satisfy the bare minimum expectations of the genre, works that transcend the genre, and works that embody the genre so precisely that the details become blurry, and instead you’re left talking about tropes. As you’ve probably already guessed, The Black Belly of the Tarantula falls into the third category. It has a murder mystery – someone is murdering impossibly attractive women (including a Bond Girl). It has a detective (Giancarlo Giannini). It is extremely violent. And it is utterly sleazy and misogynistic.

Giallo, and the crime genre more broadly, is not known for its feminism. Women are objects, women are tramps, and women are targets. In the case of the first victim, she’s all three. The character (played by the gorgeous Barbara Bouchet) is on screen for little more than 20 minutes and half of that time is spent stark naked. The other half of the time is spent teasing her blind masseur, cheating on her husband, and then being terrorized and murdered. And I don’t mean anything as prosaic as being shot. The name of the film refers to a wasp that paralyzes tarantulas with its stinger and then plants its eggs in the tarantula’s abdomen. The killer uses a needle to inject the wasp’s venom into his victims’ spine and paralyzes them. He then rips off their clothes and slowly cuts them open with a knife while they’re still alive.

The filmmakers engage in the pretense that everyone is horrified by this brutality. But brutality, directed at women, is the whole point. The murder sequences are lengthy, gory, and devoted to the display of female flesh as it is slowly penetrated by the killer’s blade. While undeniably loathsome, the intense misogyny gives the murder scenes a demented energy that’s absent in the rest of the film. The tedious domestic scenes of detective and wife and the film’s convoluted plot are poor attempts to legitimize exploitation.

.

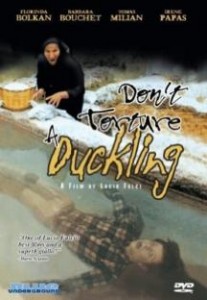

Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972)

Directed by Lucio Fulci

Starring Tomas Milian, Barbara Bouchet, Florinda Bolkan, and Marc Porel

Sometimes killing women just isn’t exploitative enough. Thank God for children.

Don’t Torture a Duckling is about a murderer who targets young boys in a small Sicilian village. There are suspects and red herrings everywhere. The killer could be the town idiot, the local witch, the overly-protective priest, or the big city harlot (Barbara Bouchet again). The police are worse than useless, and most of the detective work is done by a reporter, Martelli (Tomas Milian).

While Don’t Torture a Duckling has superficial similarities to The Black Belly of the Tarantula, the latter is nothing more than competent genre hackery with a dose of sexism. The former is a film with an actual point to make, namely that religion and superstition are terrible things. For example, one of the suspects is a gypsy witch (Florinda Bolkan) who confesses to the murder. But when the police ask her how she did it, she admits that she merely “cursed” the boys with voodoo dolls and has no idea how they actually died. The witch is not a killer but a pitiful joke, but that doesn’t save her from the superstitious townsfolk. In a scene reminiscent of medieval witch hunts, the fathers of the slain boys corner the witch and beat her to death in a gruesome sequence.

In contrast, the thoroughly modern reporter and the big city girl, Patrizia, are far more sympathetic. The treatment of Patrizia is notable in how it contrasts to treatment of women in The Black Belly of the Tarantula. Initially, Patrizia seems to be another giallo sexpot, teasing the young boys with her beauty. The film even hints that she might be the killer. But it turns out that Patrizia is neither a seductress nor a murderer – she’s just a harmless pothead who was banished to the country because of a drug arrest. The modern girl actually turns out to be a hero of sorts, and she even helps Martelli solve the mystery.

The murderer turns out to be the village priest, Don Alberto (Marc Porel), who was killing the boys to “protect” them from sexuality and ensure that they would go to heaven with stainless souls. While attempting to kill another child (his own sister!) by throwing her off a cliff, Alberto is instead pushed off by Martelli. This leads to an overdone death sequence where Alberto (actually a dummy that looks nothing like Marc Porel) slowly falls to his death as jagged rocks tear his face off, all the while flashbacks reveal his nonsensical motives.

Up with modernity, down with superstition! But the film’s point of view doesn’t survive scrutiny. Catholic priests have committed horrible acts throughout history, not least of which is the multinational child abuse scandal, but I can’t find any examples of a priest who actually murdered several children to help them avoid sin. Dying young to escape sin is simply not a Catholic obsession. Sin is unavoidable perhaps, but the penitent can always obtain forgiveness. So the filmmakers essentially invent a flaw in Catholicism that they can then throw off a mountain. One last point: the assertion that modern society is less violent than traditional society is ridiculous, especially in the country that invented Fascism (cheap shot, I know).

.

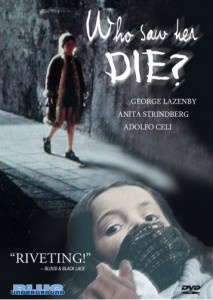

Who Saw Her Die? (1972)

Directed by Aldo Lado

Starring George Lazenby, Anita Strindberg, Adolfo Celi, Nicoletta Elmi, and Alessandro Haber

More kid killing!

Who Saw Her Die? is yet another story about a psycho killer who targets children (this time little girls instead of little boys). Franco Serpieri (George Lazenby) is an artist in Venice living apart from his daughter, Roberta (Nicoletta Elmi), and estranged wife (Anita Strindberg). When Roberta comes to visit, she is immediately targeted by a mysterious killer wearing a black dress and veil. Poor Roberta gets offed fairly early in the film, and Franco becomes an amateur detective to find out who murdered his daughter (because the police are, as usual, useless).

In most respects, Who Saw Her Die? is superior to the above two films. Venice proves to be an excellent locale for film noir. Aldo Lado turns the city of canals into a city of dark passages and winding alleys. The characters are a bit more developed than in the other gialli, and Lazenby puts in a decent performance as the grieving father. There are also a couple of wonderfully off-beat moments, as when Franco interrogates a man while playing a game of table tennis. And the score by Ennio Morricone (who also composed the score for The Black Belly of the Tarantula) is a trippy, addictive mix of rock and children’s choir. Unfortunately, the filmmakers never quite get a handle on how to incorporate the score into the film, and certain riffs such as the killer’s theme are overused.

The early scenes are kinda brilliant in a manipulative and evil way. Every time Franco leaves Roberta alone outside, the killer shows up and begins to close in. But just as the killer is about to grab Roberta, Franco returns in the nick of time, completely oblivious to the fact that he just saved his daughter. But then Franco leaves Roberta alone to play outside just a little too long, and the killer gets her. First message to parents: your child is being targeted by a serial killer at all times! Second message to parents: do not leave your child outside while you get a blowjob from your mistress. You’ll just suffer dramatic guilt afterward when your child’s corpse is fished out of the water. On the plus side, your guilt will move the plot forward.

As in Don’t Torture a Duckling, there are multiple suspects and red herrings. Suspects include an evil businessman, a child molesting lawyer, a priest … I won’t waste your time, of course it’s the priest. But it gets better! He’s not just a priest but a cross-dressing priest. According to the Psycho Rule, that multiplies the evil by a factor of four. The film chickens out at the end though, when it is revealed that the killer was only impersonating a priest. The filmmakers were likely worried about offending Catholics. Though I suspect they were not so worried about implying that priests are murderers (Don’t Torture a Duckling was released in the same year) and more worried about implying that priests are cross-dressers. Some insinuations are beyond the pale.

Perhaps if cross-dressers had their own country and a global institution with millions of adherents, filmmakers might think twice about portraying them as degenerate child-killers.

“the crime genre more broadly, is not known for its feminism.”

Pulp crime maybe. More generally though (at least in terms of crime novels), there are plenty of feminist authors and considerably more female readers than male.

If you can find it, you should check out Investigation of a Citizen above Suspicion, which is a great twist on the mystery aspect of the genre. Don’t Look Now is another favorite, even if it was directed by a Brit.

The gender-exploitation question is interesting because I always thought literary mystery/crime audience has a disproportionate amount of interest in and from women.

I know there are more female readers than male, but I don’t have any stats as to what genres they read, so maybe there are more women reading crime novels nowadays. But I’ll respond with three points.

First, I’m talking about the crime genre in more historical terms – and for the most part, crime was a male-oriented genre. I’m sure that’s changed in recent decades, especially in the publishing industry (less so in movies, I think.

Second (this is a minor point), I don’t know if gender preferences for certain genres breaks down in the exact same way in Italy as they do in the US. Maybe the do, but I have no clue what Italian women are reading or watching.

Second, just because women read it doesn’t make it feminist. I read “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” recently, and from what I’ve heard online it is HUGELY popular everywhere, especially with female readers. But anyone who claims that it’s feminist should have their head examined, because it’s little more than an empowerment fantasy for middle-aged men who want to sleep with goth chicks.

Yes, just because women read it doesn’t make it feminist. does that prove that crime lit aimed at women is overwhelmingly like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, though? FWIW the handful of women crime writers i’ve read have been Japanese (Out and All She Was Worth were the best of these) and neither one was an empowerment fantasy for middle-aged men who want to sleep with (insert stereotype here). Neither was great but they were both relatively thoughtful and interesting in dealing with sex and gender roles.

but you’re right, i can’t speak for the whole genre, and film and literary genres are different. i’m having trouble thinking of any good feminist crime movies, and I’m much more familiar with those. still, check out investigation of a citizen above suspicion, if you can.

Thelma and Louise is a feminist crime movie — not one I’m particularly fond of, but that’s definitely what it’s going for.

The Last Seduction, possibly. Linda Fiorentino is by far the most enjoyable character, and she wins in the end. In theory she’s the bad guy, but in practice it’s a lot less clear.

Women in Prison films are kind of/sort of feminist crime movies maybe…but they end up in a different genre, which sort of proves the point.

The Janet Evanovich books are basically crime/adventure stories for women…but they end up reading more like romance really. Still, they’re shelved in mystery I think.

Ave- I’ll check out the movie.

You’re right that the Millenium series may not be representative of crime fiction generally … but it is really, really popular around the world.

I have no familiarity with Japanese crime stories, most of my knowledge is of American and some European stories, and they always struck me as “guy” entertainment, a few exceptions like Miss Marple or Nancy Drew notwithstanding.

Noah – Silence of the Lambs at least aims at being a crime story with a strong, female lead, though it’s usually grouped into horror films, which kinda proves my point.

As for crime literature, I have an anecdote which probably demonstrates nothing but it is pseudo-relevant. One of my female co-workers loaned me a crime novel, “Scavenger” by David Morrell (the guy who wrote Rambo: First Blood). She really, really liked it, but when I read it, I was surprised by how thoroughly it fit into the action blockbuster mold (this is one of the novels that is obviously a script for the movie adaptation). Strong male lead, lots of action, explosions, techno-fetishism. But it did have a likable, female co-lead and a little romance. I think certain story-telling formulas work well with both mean and women. And obviously it’s easier to sell crime stories to women if you don’t brutally slaughter all your female characters.

Don’t know about the books, but the Dragon Tattoo movies pretty clearly set up the titular girl as being in control of the sexual relationship she has with the reporter. She’s the most capable individual in the entire trilogy, too. Is that feminist? Depends on your definition, I guess, but it certainly contains an empowered female character.

And Patricia Highsmith is one of the best mystery writers, regardless of gender.

Charles – The fact that Lizbeth is “in control” of the relationship doesn’t necessarily make it a feminist screed. Being sexually dominated by a young woman is a common middle-aged fantasy as well. I think the depiction of Blomqvist is far more relevant, since he’s portrayed as thoroughly ordinary and not exceptionally attractive – a typical middle-aged guy that middle class readers can relate to. Yet the female characters all seem to throw themselves at him. I just don’t buy it – it’s a cheesy fantasy.

As for Lizbeth … I’m not so arrogant that I’ll tell women who they can and can’t find empowering. Personally, I wasn’t impressed by the character, but obviously your mileage may vary.

All I was saying was that I don’t agree it’s a male-empowerment fantasy. Why not a female empowerment fantasy? The girl wasn’t too much to look at either. Lisbeth winds up dominating just about everyone in the film and getting revenge on those who wronged her.

I suspect crime movies probably are primarily marketed at men. Crime novels and TV shows, on the other hand, are definitely seen by more women than men. They’re mostly marketed in a way designed not to put off either sex though.

Crime novels that overlap substantially with the romance market (Hoag, Cole, Evanovitch, Robb and so on) are the obvious exception to the rule, obviously. Overall, at least 70% of the overall readership is female in my experience (though I’ve seen articles that put the figure as high as 80%).

I think what has changed over the past few decades is that a majority of the biggest sellers in crime fiction over here are now written by women as well as read by them (and that has a spillover effect in terms of what gets adapted for TV too – Hollywood crime movies seem more often to be adapted from books by men, which you can make of what you will). Not sure if the same applies in the US but quite a few of those writers are Americans so I presume so.

“First, I’m talking about the crime genre in more historical terms – and for the most part, crime was a male-oriented genre.”

The traditional whodunnit that once dominated crime fiction were marketed at least as heavily to women as to men. Even the early hard boiled stuff (Chandler and Hammett and so on) had very large female readerships, at least here in Britain, right from the start. Sherlock Holmes has had a very large female readership right from the beginning too.

As with crime movies (especially exploitation movies), crime comics – be they American, European or Japanese – mostly seem to be primarily aimed at men. I’m thinking maybe, in the case of crime fiction, the medium is more significant in gender terms than either the genre or the strength (in terms of violence) of the material.

“Second, just because women read it doesn’t make it feminist. I read “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” recently, and from what I’ve heard online it is HUGELY popular everywhere, especially with female readers. But anyone who claims that it’s feminist should have their head examined, because it’s little more than an empowerment fantasy for middle-aged men who want to sleep with goth chicks.”

I dunno about the US but over here the marketing for that series was pretty much gender neutral.

It was certainly intended by its author to be a feminist work but I don’t think its arguable success in that department (the question of whether the series is empowering or exploitative has been going on for a long time and both sides seem pretty entrenched at this point) detracts from the many other crime writers who could fairly be described as or self-identify as feminist. From a quick scan of my own bookshelves, Sara Paretsky, Natsuo Kirino, Kerstin Ekman, Liza Marklund, Pernille Rygg, Maj Sjowall, Karin Alvtegen, Anne Holt, Yrsa Sigurdardottir and Karin Fossum all fit the bill (and I’m sure my tired eyes are overlooking quite a number of other, mostly European, writers).

For what it’s worth though, I know a lot of women that have read the Millennium trilogy and none of them found it objectionable but the film adaptations were off-putting to a couple of them. I tend towards the opinion that both sides in the debate are right – he is an authorial wish fulfilment figure (I’m not sure “power fantasy” quite fits) and she is a genuinely strong female protagonist.

Either way, I found the books to be moderately enjoyable but there’s a host of other Scandinavian crime writers I’d rate a great deal higher than Larsson.

“are the obvious exception to the rule, obviously.”

Argh. Somebody shoot me.

“Overall, at least 70% of the overall readership”

Twice.

Ian – don’t sweat it, I do that sort of thing all the time.

I think you are right about novels: so I hereby retroactively qualify all my above comments so that I’m only discussing the crime genre in movies.

I’m not surprised Sherlock Holmes has a prominent female following, it’s fairly gender neutral (someone else can bring up the Holmes/Watson slash if they want to). Most American crime shows are police procedurals like CSI, and they’re, at least on the surface, gender neutral too (though the early seasons of CSI had some queasy gender attitudes just below the surface).

Initially, I was surprised that the hard-boiled stuff was popular with women. A lot of those novels were overtly misogynistic. But then I thought about it some more. As I mentioned in the post, misogyny can give a story a certain energy, it can actually be a creative tool. Misogyny is at the root of the femme fatale, which has become an enduring archetype that a lot of women appreciate, for obvious reasons.

Everybody knows.

They’re just good friends.