Dan Kois, who reported on Lynda Barry’s teaching methods in a recent New York Times article kindly stopped by recently in our comments section. Here’s what he said:

I wrote the Lynda Barry piece in the Times Magazine, and have been reading this comment thread with great interest.

With regard to Barry and craft, I think it’s useful to separate her writing and her teaching. I think Lynda’s comics and novels do demonstrate that she has an interest in, and a flair for, the crafting of stories and scenes in ways that your average fiction-MFA instructor, for example, would appreciate.

In her teaching, though — at least as I witnessed it, and as she discussed it with me over many, many hours — I would argue that Lynda is, indeed, determinedly anti-craft, and in that regard, very very different from any writing teacher I’ve ever encountered, including in MFA programs where I’ve been a student or an instructor. There was a whole section of the piece that got cut for space that talked about the way that Lynda’s class deals heavily in inner process — that is, *where the ideas come from*, not just *how you craft the ideas into effective prose* — in a way that is anathema to nearly every creative writing teacher I’ve ever encountered. As the novelist and teacher Madison Smartt Bell told me, “I avoid that stuff like the plague, because it’s just too dangerous to deal with.” But Madison is of the opinion — as am I — that Lynda has found a method to teach inner process that is a) not damaging to students or dangerous to her and b) surprisingly effective for nearly everyone who takes her class.

To the commenter above who wrote:

>>But once Barry helps students open themselves up to their creativity, she does also advise them on editing and refining their work.That’s only true in a limited sense. She does discuss editing to some extent, but only in exceedingly broad terms. No students have their work edited in the class, because no students are allowed to discuss their work in the class, or even outside class, for the duration of the course. That’s a strict rule, and one that Lynda holds to herself; she wouldn’t even talk to me, a reporter, about any of her students’ work.

As I mention in passing in the article, Lynda makes the case in her class that narrative structure — that is, one major component of the craft of storytelling — is a natural muscle that most humans have. The example she gives is the way you tell a story depending on whether you have one minute to tell it or ten minutes to tell it; she points out that it’s a natural tendency to construct the details of a story in a manner appropriate for the space that one has to fill.

Now, do I think that Lynda has never once thought about story structure in writing her comics or (especially) her novels? No. (Though ask her about how she wrote CRUDDY and she’ll tell you a tale of years of woe stemming from reading book after book on story structure and novel-writing, which ended only when she threw it all away and painted the novel in ten months with a brush.) But I do think she holds firm in her teaching to a credo that for the students she’s working with, craft is not a useful thing to teach; in fact, craft gets in the way of the stories these students want to tell.

Dan, if you’re about…I’m wondering if you can talk more about what you mean by “inner process”? As I mentioned on the other thread, the writing classes I had were definitely focused on generating ideas (through journals, recording dreams, reading other books, what have you.) It sounds like you’re talking about something else, though.

Interesting. I’ve never been in a writing class (at the undergrad or MFA level) that dealt with idea generation or how you transform your own experience into fiction. Here’s the quote from Madison Smartt Bell:

“In teaching writing, there’s not been too many gestures in the direction of inner process, with the exception of Gordon Lish’s workshops in the ’70s and ’80s, first at Columbia and then the so-called master classes that were written about a lot of the end of the 80s that he just ran out of rich women’s houses. I was teaching at the 92nd Street Y then, I’m only hearing about it secondhand, but I felt like he was getting involved with the psyches, with these students, and indeed they were permitting it.

“It very soon began to look to me from the outside like a cult. I just thought you know I’d seen them before and during and I’d think ‘man this is weird. This is like people who went to the Gaskin farm.’ These are people who have had their minds been taken over by some peculiar sort of group ethic that happens

in this case to be about the processes that are supposed to make them inspired to write their own work and I don’t feel like this is necessarily good.

“I talk about inner process a little bit in my classes and then I say, ‘This is important. It’s more important than all this craft stuff that we’re actually going to talk about and that I’ll try to teach you. This is what really matters, but you have to do this by yourself. Lock the door. Go inside, lock the door and do it alone, and you communicate with your angels and demons any way you want to and don’t let anybody else in unless, you know, you have a relationship that warrants that, which is not your relationship with me and probably not your relationship with anybody that you happen to know because they’re in the class with you. I mean, be advised.’ I think that for me that’s safe and I can do a lot with enough limitations, but when I was talking to Lynda, I thought, godammit, you know, she found a way to do inner process with people that she’s working with that’s not dangerous, or so it seemed to me.

“The risk in these is always a surrender of individual control. If you start sharing your processes of inspiration and your creative intuition, you actually kind of give it up and it goes out into the group, and then you maybe can’t get it back. You become dependent on the group — this is how cults work also — and especially dependent upon the leader. Well Lynda, in my impression — you were in the class — She’s like the most unleaderly leader you could possibly imagine. I think she’s extraordinarily ego-free.”

Huh. That doesn’t sound much like what I’m talking about (this is at Oberlin undergrad.) It wasn’t cultish or even very personal; just very much —”these are some ways writers generate ideas.” Very workmanlike.

I also have to say…I find the suggestion that the most important part of writing (or I presume any art) is the inner process of inspiration just really not at all what my experience of creating art (of whatever sort) is like. Art/writing really seems like something that takes place in a communal medium (language or images). It’s a conversation, which means that inspiration from it is at least as much outer directed as inner-directed. You get inspired by other poems or other art or other ideas, not by some sort of mystical inward-turning (not that mystical experience can’t be inspiring — but religion is a community too….) I think that’s part of what Caro has been trying to get at when she talks about the importance of reading for writers, or what I mean when I was saying that craft and content aren’t really separable.

Have you read the Artist’s Way, Dan? Would you say that Barry’s approach is different from Cameron’s, or are they coming from a similar place?

I have not, so I have no sense of The Artist’s Way as anything other than that foo-foo book that people cite all the time as inspirational. Maybe it is not foo-foo at all! I don’t know.

It’s hideous beyond all description. “Foo foo” is too benign.

Really, it’s like the worst thing I’ve ever read, I think.

Dear Dan Kois, I’m the reader who objected to your characterization of Barry’s attitude towards craft. Before I comment further though I did want to say that I thought your article was excellent and really captures the Lynda Barry Experience extremely well — I thought about writing about Barry as a teacher myself and have been daunted by how hard it is to capture her sparkling classroom presence.

About craft. It might be good if we distinguished between two different types of craft — one is a kind of mechanical surface facility gained from learning the rules — i.e. people who write stories or movies by a strict formula. Barry is definitely against this type of craft learning, seeing it as one of the many inhibitions to creativity.

But I do think that Barry’s approach to art allows for another type of craft — not a set of rules or techniques to master but an ability to reshape basic narrative and visual forms for effect. The example you give is a good one: “The example she gives is the way you tell a story depending on whether you have one minute to tell it or ten minutes to tell it; she points out that it’s a natural tendency to construct the details of a story in a manner appropriate for the space that one has to fill.” This sort of instinctive narrative sense might be innate (a sort of muscle, as you say) but like any innate sense or muscle it can be built on, refined or developed. At least in the classes I sat in on, Barry was interested in getting students to not just access this innate narrative sense but also to develop it and to be mindful of the ways stories can reworked or reshaped. She’s not just preaching a creed of automatic writing.

It’s a subtle distinction but I think that Barry is against a superficial sense of craft mastery (which can inhibit creativity) but wants artists to gain confidence in their ability to rework and reshape their material (which is a different and I would say higher form of craft knowledge).

@Noah. How does The Artist’s Way fit in your larger cosmology. Is it Philip Roth > Julia Cameron or Philip Roth < Julia Cameron?

Julia Cameron is worse than just about everything. Even Philip Roth.

Thanks for expanding on Barry’s view of craft by the way, Jeet.

I feel like we’re sort of groping in the dark here. Dan did say in his comment that Barry is “determinedly anti-craft.” But I can’t imagine someone with Dan’s background uses the term “craft” to mean something as limiting or strict as “a kind of mechanical surface facility gained from learning the rules.” My assumption would have been that he meant it in something closer to Barth’s sense – “the rudiments of, say, fiction, together with conventional and unconventional techniques of their deployment.” But that doesn’t sound terrifically different from “an ability to shape basic narrative and visual forms for effect” — unless the emphasis is so heavily on “basic” that no “technique of deployment” is really necessary.

So I’m still pretty confused — I think the “inner process” is much clearer, but in what sense is Barry anti-craft?

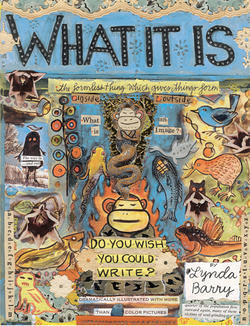

@Caro. I agree that “we’re sort of groping in the dark here.” Part of the problem is surely that we’re leaning too heavily on Dan’s article. As excellent as it is, the article is a second hand account of Barry’s pedagogy. It might be better we we used What It Is or Picture This as a springboard. The two books really grow out of Barry’s teaching, and offer insights into it.

The other clarifying point I’d make is that Barry is less interested in “fiction” than in something more primal, which is “story-telling.” Storytelling can be seen as the embryonic form of fiction, so if you want to write fiction you usually need to develop your skills as a story-teller. (I say usually because there are good and interesting fiction writers who really have no talent at all as storytellers or interest in storytelling.) There is a craft to storytelling just as there is a craft to fiction, and I’d say (at least in my experience) that Barry is more interested in the former. Storytelling feeds into fiction but it can also feed into other arts — theater, movies, stand up comedy, simply tale telling (of the Mark Twain variety).

Following Walter Ong, we can locate the origins of storytelling in orality, and the origins of fiction in literacy. Part of the problem of bringing in theorists like Barthes (or Derrida, etc) is that they are on the far end of the literacy spectrum. In some ways, Ong himself might offer more clues as to what Barry is up to since he was supremely sensitive to the peculiarities of orality.

Hope this helps.

I agree, Jeet — but all that is consistent with what’s in Dan’s article and the discussion up to this point, though, isn’t it? The storytelling function is close to Barth’s “material,” or Dan’s “inner process”? I mean, she could be pro-storytelling craft and still anti-writing craft.

And I’m more concerned with clarifying Dan’s sense that she is, in fact, “determinedly anti-craft” when it comes to writing. I still think that’s a problem, even if it doesn’t extend to the craft of storytelling, because good storytelling, although debatably necessary, is certainly insufficient to make comics into literature or to bridge the gap between the discourse community of fiction and that of comics. An approach focused on storytelling could be inclusive and valuable to literary-minded people, but if the affection for orality is accompanied by a prejudice against “advanced literacy”, then it will be exclusionary and limiting.

That is, Barry doesn’t have to have the prejudice to have the affection…it’s not an either/or choice between orality and literacy, at least not in pedagogy. Even if she chooses to explore orality at the expense of literacy in her own work, she doesn’t have to institutionalize that for everybody else as a teacher.

That’s always been the aspect of this that’s concerned me — not the things she’s in favor of, which sound wonderful and inspiring and really useful, but the things she’s against. I think teachers have to be careful being “against” things in ways that artists really do not.

Maybe it’s more useful/accurate to say that Lynda finds discussions of writer’s craft essentially useless in the specific setting of her class. Students are encouraged to engage their innate sense of storytelling, but at no point are those stories revised, edited, shaped, commented upon, or evaluated. No attempt is made in the classroom setting to shape the raw material that comes out of the students into a more polished/crafted/well-written/saleable/inauthentic (pick an adjective, depending on your biases) form.

Would Lynda object to students, after the class is over, doing the work to shape that material, whether in another class setting or on their own? I can’t imagine so, although she’s careful in class to assign value to what it is that her students are creating in the moment, as opposed to what it is they may create in the future.

@Dan Kois. That’s fair enough.

@Caro. “it’s not an either/or choice between orality and literacy, at least not in pedagogy.” Well, ideally it doesn’t have to be either/or. But the contemporary academy is so biased in the direction of literacy that it is sometimes necessary to make a full-throttle case for orality simply to have some balance. Ong is very good on this point.