Sina Evil is a comics artist, best known for his self-published autobiographical comics series BoyCrazyBoy. He is also completing aPhD on the history of queer comics. He is a huge fan of the Golden Age Wonder Woman. His website is www.boycrazyboy.com.

This is the second of two posts on Gay Ghetto Comics. The first is here. Portions of this post were delivered as a talk at “Materiality & Virtuality: A Conference on Comics” at Leeds Art Gallery on Friday 18th November 2011.

________________________

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s various queer people felt alienated from the “official” gay and lesbian community and culture – but nevertheless desired some sort of gay community/culture. Among them were cartoonists who felt that their work did not “fit in” with the glossy, mainstream gay magazines. Inspired by the burgeoning zine culture’s “do-it-yourself” ideals, these new LGBT cartoonists began to produce and distribute their work through self-published comics or small independent presses. These cartoonists were critical of homophobia, but far less interested in affirming a sense of shared gay identity and community. Instead they tended to focus on their personal lives and identities, critiqued mainstream gay culture as conformist and commercialized, and created alternative visions of gay life and culture.

Robert Kirby was one of the pioneers of this new queer cartooning when he published the queer alternative comics anthology Strange Looking Exile in 1990, which ran for 5 issues, and was followed by another anthology, Boy Trouble, in 1994.

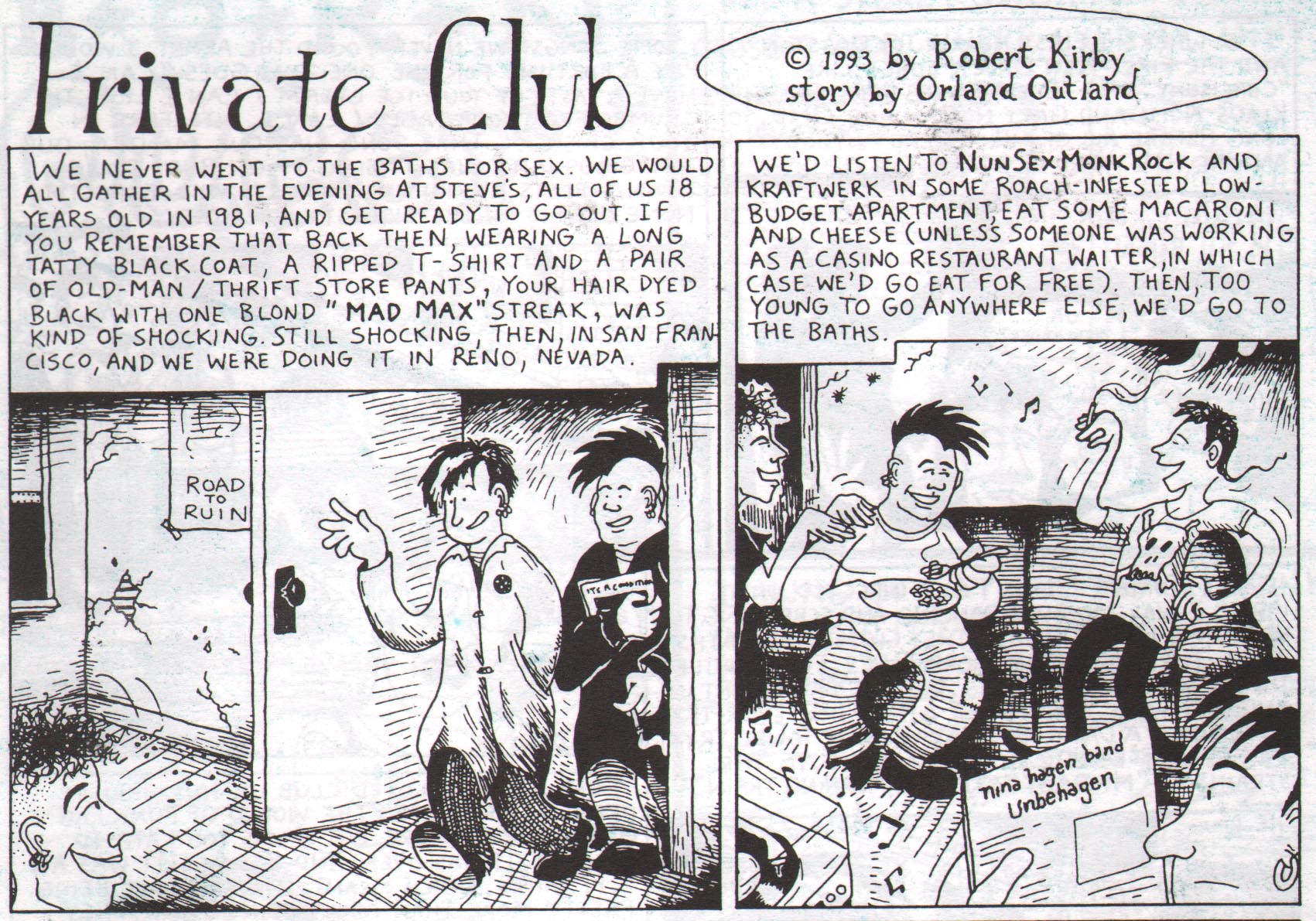

I will now discuss Kirby’s story “Private Club”. The story was adapted to comics form by Kirby from a short autobiographical prose story by Orland Outland. Although not written by Kirby himself, “Private Club” nevertheless typifies many of Kirby’s own concerns as a writer, and his representation of community and “belonging” in his comics.

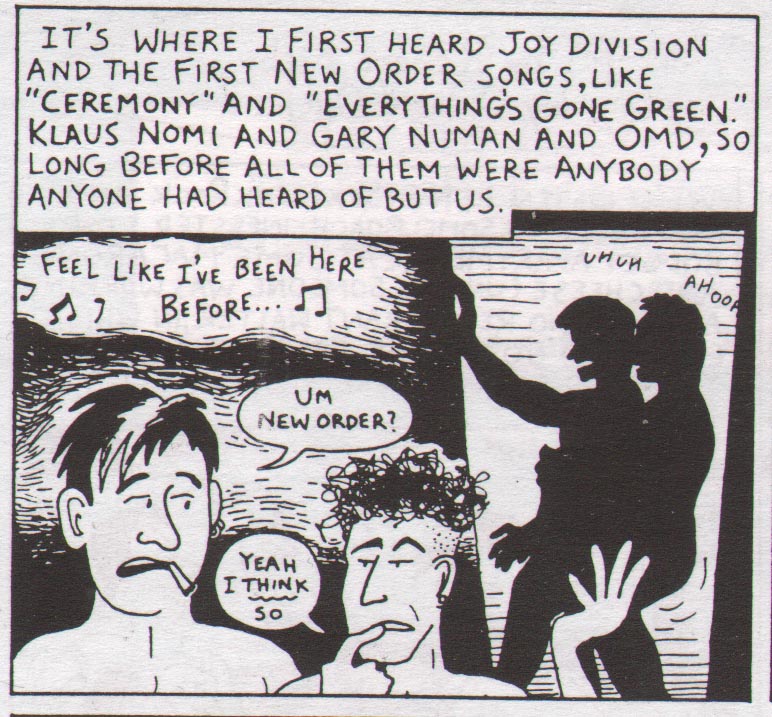

The story is narrated by Orland himself – a middle-aged gay man, a former punk, he reminisces about going to gay baths with his teenage friends in the early 1980s in Reno, Nevada. These teenage queers, too young to get into gay bars, would go to the baths not for sex but “for the music.” Orland describes how a DJ in the baths at San Francisco was making tapes of “the best music in the world” which he would send to the club baths in Reno. The young protagonists of “Private Club” are portrayed as awkward and unsure of themselves, afraid of the highly sexually charged gay subculture, but also more focused on having fun with their friends and enjoying music.

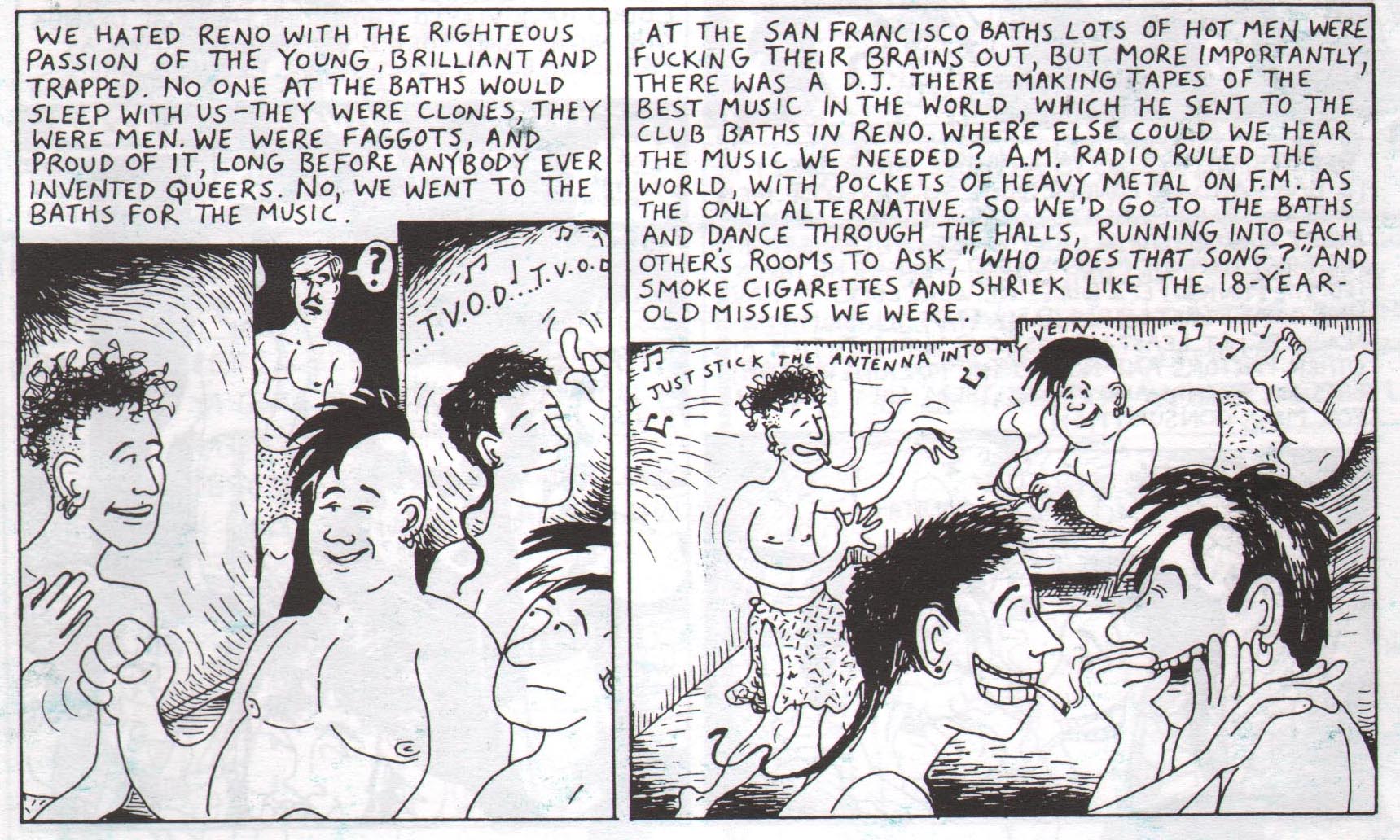

Throughout the strip the narrator’s alienation from “mainstream” gay scenes is highlighted. He and his friends are rejected by the majority of the gay men who frequented the baths in his hometown in Reno, Nevada: “No one at the baths would sleep with us – they were clones, they were men.”

The young punks themselves reject this rejection, emphasizing their difference from the other gay men, turning their difference into a badge of honour: “We were faggots, and proud of it, long before anybody invented queers.” In one panel Kirby depicts Orland and his friends dancing and singing along gleefully to “T.V.O.D.” by synth-punk act The Normal, while a muscular, mustachioed gay man peers from behind a wall in the baths, bemused and annoyed at being interrupted while cruising and having sex.

The teenage faggots’ behaviour is an example of what Michel de Certeau describes as “tactics” in his book The Practice of Everyday Life. De Certeau aims to outline the way individuals unconsciously navigate the everyday and distinguishes between what he calls “strategies” and “tactics”. Strategies are employed by institutions and structures of power who are the “producers” of culture, and seek to control ordinary people; on the other hand, Certeau sees individuals as “consumers” who use “tactics” to negotiate some sense of agency in environments defined by the producers’ strategies. A classic example of “tactics”, described by de Certeau, is the secretary who “poaches” time and materials from her boring office job to write a love letter – on company time and using the institution’s resources. This illustrates Certeau’s argument that everyday life works by a process of poaching on the territory of others, using the rules and products that already exist in culture in a way that is influenced, but never wholly determined, by those rules and products.

Like Certeau’s “tactical” secretary, the young faggots of Outland and Kirby’s strip use the space of the gay baths for something the institution does not intend the space to be used for, transforming parts of it into their own “private club” – as the story’s title implies, a private space (albeit in semi-public) where these teenage punks have the freedom to be themselves, listen to their favourite punk/synth-rock music, “smoke cigarettes, and shriek like the 18-year-old missies we were.” By appropriating space in this way the young faggots create for themselves a different kind of “community”, an alternative reality.

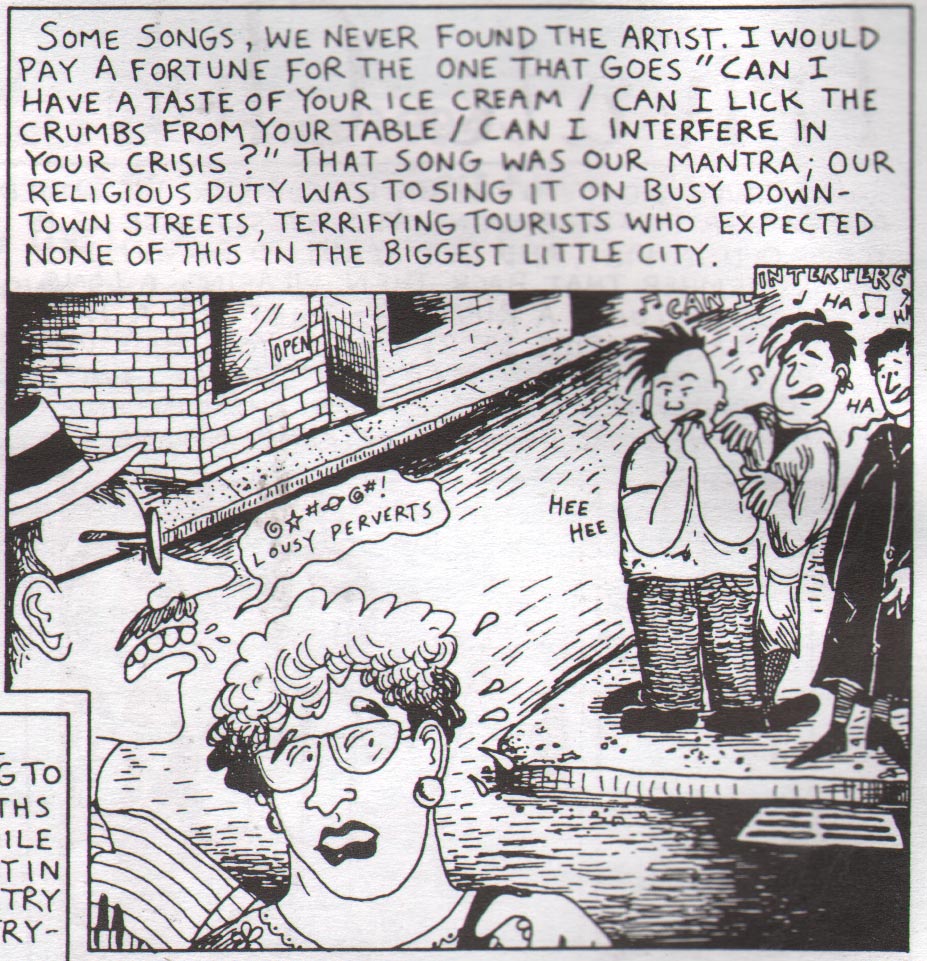

This alternative reality is one that contrasts with the young punks’ repressive, heteronormative surroundings in Reno – in one panel Orland and his friends are depicted standing on a street corner, delighting in singing offensive punk lyrics loudly in an effort to frighten heterosexual passersby – another example of Certeauian “poaching.”

However the young faggots also seem to enjoy interfering and disrupting the “normal,” everyday rules of the game at the gay baths, “poaching” on the territory staked out by the sexually confident community of “clones” that are the club’s primary clientele.

This disruption is manifested through their sloppy, “punk” appearance and their decidedly unsculpted bodies, which contrast with the more groomed and “worked-out” looks favoured on the mainstream gay scene, defying mainstream gay culture’s normalizing disciplinary regimes.

A further disruption of the bath’s status quo is the young faggots’ ebullient enjoyment of “unusual,” punk music, and their playfully effeminate “camping,” which contrasts with the more “serious,” “tough” and “masculine” postures adopted by the majority of the bath’s visitors.

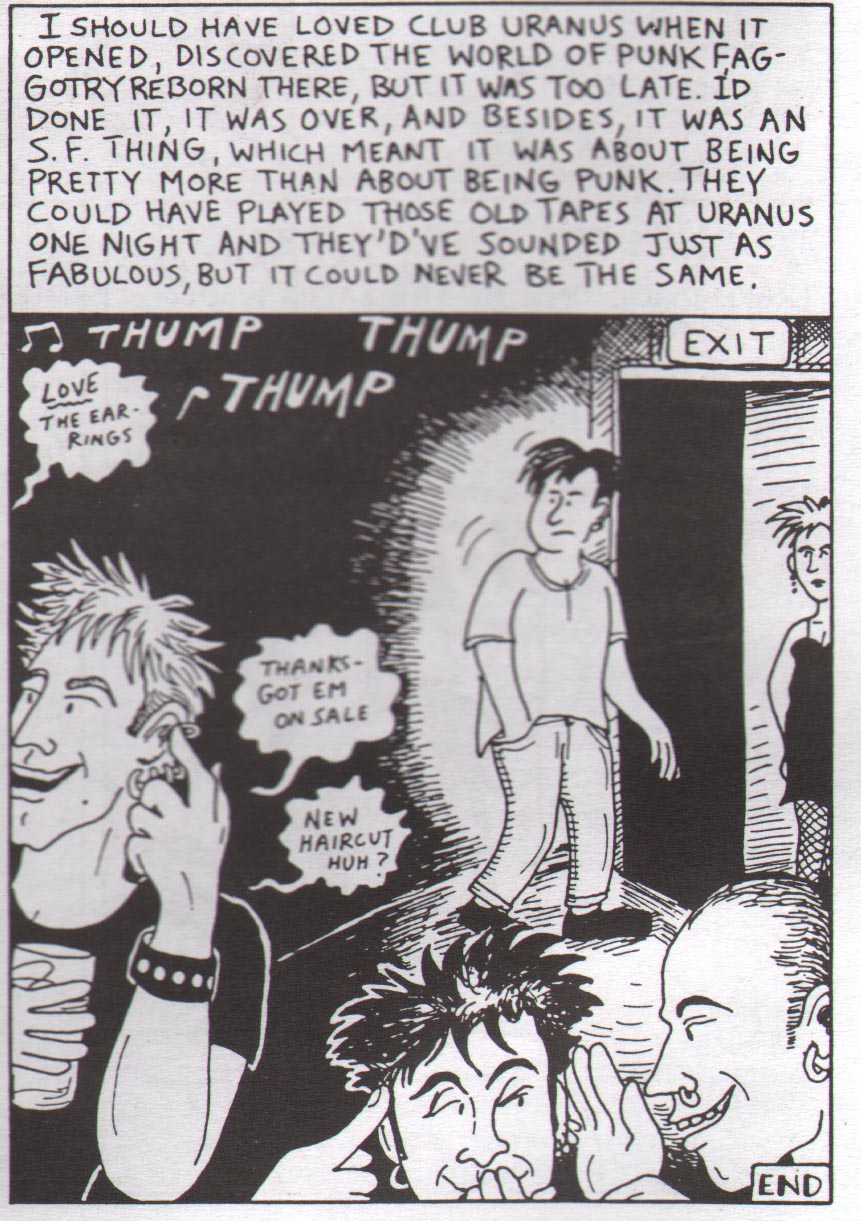

The strip’s protagonist, Orland, describes the baths as “our secret world” of “punk fags in the middle of nowhere,” and distinguishes his friends from the “gay clones.” The story closes in the present day, with Orland visiting Club Uranus, a gay punk rock club in San Francisco; Orland notes that although in theory he should have loved this club, in fact he experiences it as a sanitized, commercialized version of the more amorphous, less official space he had “poached” and shared with his friends.

Kirby portrays Club Uranus as populated by handsome athletic gay men sporting fashionable tight T-shirts, spiky haircuts and trendy piercings, discussing their accessories (“Love the earrings”/”Thanks – got ‘em on sale”) – the narrative caption reiterates that in contrast to the “private club” of Orland’s youth, commercial “punk” clubs are “about being pretty more than about being punk” – San Franciscan queer punks are represented simply as another kind of gay “clone”, another commodified, conformist gay identity.

In my interview with Kirby he described himself as, at one time, feeling like “a square peg surrounded by many round holes” (interview, Minneapolis, Minnesota August 18th 2008) – and this is how he represents Orland, the protagonist of “Private Club” – alienated not only from the gay mainstream “clones” but also from the gay punk scene which in theory he “should” feel a part of; the story, then, like many of Kirby’s comics, emphasizes the tensions and conflicts inherent in the notion of community.

At the same time, “Private Club” suggests that a kind of postmodern experience of community is possible and indeed valuable – the strip emphasizes the importance of Orland’s teenage bonds with his punk faggot friends, and in some ways – and for a necessarily brief time – this friendship group, Orland’s “private club”, does operate as an ideal(ized) community where the young punks’ difference from their heteronormative small town and from the norms of gay culture can be celebrated and enjoyed.

Many familiar elements of gay alternative cartoonists’ representation of mainstream gay culture are present in “Private Club”: “Mainstream” gay men (whether in repressive small towns or metropolitan gay ghettoes) are represented as vacuous, body fascist, and conformist, and are visually represented (on the whole) as slim, athletic, and fashionable in a commercial, “mainstream” way. They are akin to the types of gay characters prominent in comics like Troy, Joe Boy, Kyle’s Bed & Breakfast and Chelsea Boys, but in “Private Bath” they are background characters and figures of mockery, in contrast with the punky young faggots who are the story’s protagonists. The young protagonists’ “punk” gay identities are also posited as an alternative to mainstream gay identity – this is a kind of queer identity built around references to “alternative” fashion, music and taste. Characters like the young punks of “Private Bath” (re)appear as protagonists throughout Kirby’s oeuvre, and can also be found in the work of many of the other gay alternative cartoonists who began publishing their comics independently from the 1990s to the present day.

The one that goes “Can I have a taste of your ice cream” etc. is by Delta 5 and appeared a few years back on a compilation called Disco Not Disco. This is in reference to the panel above in which the narrator and his crew are standing on a corner being sworn at by an R. Crumb-looking dude.

…It’s a great record.