I’m reprinting two related reviews; the first appeared on Madeloud; the second on Splice Today.

_______________________

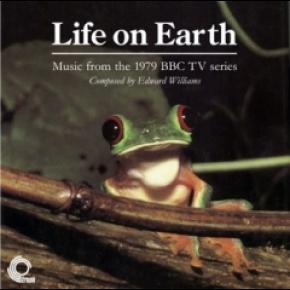

Edward Williams – Life on Earth: Music From the 1979 BBC TV Series

I actually cried when I missed an episode of the David Attenborough BBC mini-series Life on Earth.. I was in middle school at the time, and my family watched the show religiously every week, but I had a swim meet, and we’d just forgotten. Worse, it was the reptile episode. I loved reptiles.

It’s hard to believe I remember all that now, three decades later. I remember, too, that much as I loved the show, the end of each segment was thoroughly disturbing; you’d watch these wonderful, strange animals for an hour, learn about their habits and their lives, and then, at the end, David Attenborough would explain in his matter-of-fact, British voice, how man’s relentless expansion was inevitably going to kill them all.

And yeah, I remember the soundtrack too. Not the melodies or anything, but the broad outlines of the music; quiet, translucent, and fey; chamber music to contemplate extinction by. It’s bizarre how clearly the show comes back to me while listening to this newly released reissue of music from the series. The plangent woodwinds, the splashes of strings, the dischords that never resolve but just drift away — I can see the water dropping into the pond, or the butterfly coming out of its cocoon, or the hummingbird wings slowed down so that Attenborough could count the beats.

Obviously, I’m older at this point, and while the music seemed sui generis back then, it now fits into a recognizable context— which is to say, composer Edward Williams loves, loves, loves him some Debussy. But even so, there’s a strangeness and a humor here that’s hard to resist. The wonderfully named track “The Sex Life of Ferns” starts with a light percussive patter, as if all those spores are nervously shuffling their bits in anticipation; then, towards the end, there’s a lazily triumphant woodwind, and you can imagine various leafy greens rustling in a satisfied manner as the sun sinks low in the distance. “Big Mammals” has a slow, swaying lope with just a touch of Tarzan jungle drum, so you can almost see those big trunks swaying. And then there are the lovely albeit somewhat unfortunate Orientalisms on “Japanese Macaques.” It’s all so melancholically precious, or so preciously melancholy. I don’t know if Donovan ever saw Life on Earth, but if he did, he would have understood.

Perhaps my favorite track is the final one, taken from the last episode in the series, “Man.” I pretty much hated “Man” at the time; I wanted to see reptiles biting things and frogs jumping, and elephants trundling, so a bunch of people walking through cities was just not what I was parked on the couch for. Yet, despite my disinterest, Attenborough’s final words have remained with me for most of my life, and it was a jolt to hear his narration excerpted here. “The fact remains that man has an unprecedented control over the world and everything in it. And so, whether he likes it or not, what happens next is largely up to him.” The music for the finale is an odd duel between a inspiring fanfare and a mournful little solo violin theme. Eventually the fanfare seems to win out…but in the last second or two it trails off weirdly, as if embarrassed. It’s an appropriately uncanny moment. In this mini-series and album, life doesn’t so much dominate the planet as haunt it, passing across the surface of the earth like a shadow, or an oddly vivid memory.

_____________

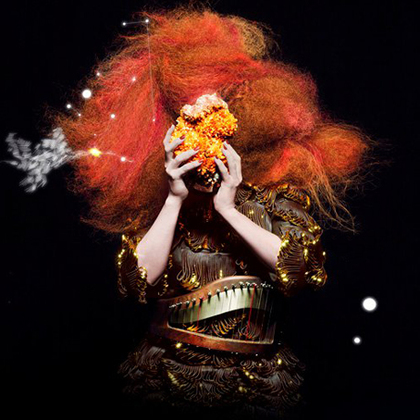

Bjork: Biophilia

Bjork is Bjork. Over the years she’s become one of those artists who is a genre unto herself. Though she’s got connections to the fey new folk movement and links to the fey end of New Age electronica and an affinity for other fey Icelandic post-rock romantics like Sigur Ros, the truth is that when you listen to any of them and Bjork, she becomes the meme and they become the iteration. Or, to put it another way, they all sound like Bjork more than Bjork sounds like them. You can compare her to whoever till your hair turns pixie polycolors, but Bjork is not post-rock folk electronica. She’s Bjork.

Which is why her latest effort, Biophilia, gave me a start. Not that it’s different from her past releases—if you’ve heard Vespertine(2001), or Medulla (2004), or Volta (2007), you’ve got a good idea what to expect from Biophilia. It’s just that all of a sudden, the Bjork sound didn’t sound like Bjork. It sounded like Edward Williams’ music for the David Attenborough mini-series Life on Earth.

What made me think of Williams’ quiet, Debussy-like score are no doubt Biophilia’s lyrics. You can get the gist from the song titles: “Moon,” “Crystalline” and “Solstice.” The album is post-rock folk electronica for the natural world. You listen to its plangent blips and murmurs and visualize plants opening or birds’ wings beating in motion so slow you can see each feather shudder. Nature, in Bjork and Williams, is figured as a series of disturbingly vivid tableau arranged for uncanny contemplation. At the beginning of “Hollow,” the echoey, arthymic keyboard sounds patter forward, then pause, then patter forward, then pause, like a small furry creature scuttling across the ground towards food. “Moon”‘s plucked lilt could be the background for a butterfly slowly coming out of its cocoon. “Thunderbolt” is even more explicit: “Staring at water’s edge/Cold frost on my twig/My mind in whirls/Wandering around desire/…Craving miracles.” Then at the end of the song, the electronics start burping like a series of frog calls. Suddenly Bjork isn’t Bjork. She’s library music for a nature special. How did that happen?

“Virus” seems like an attempt to explain the process. “Like a mushroom on a tree trunk/as the protein transmutates/as I knock on your skin/and I am in,” Bjork sings in her usual hoarse, soaring precious diva style as the music drips and clinks, water falling on chimes. Nature is both a smooth vision on the eye and an ominous visitor moving under the skin. Nothing is really itself. “My sweet adversary,” Bjork calls her lover/disease, as the distanced music and its surface prettiness turn her into an aestheticized transient shadow. If you watch nature, and nature is you, then you are both inside and outside, a ghost infection haunting yourself. At that point, you can hardly be surprised when you become something else, even if that something else is a 30-year-old BBC miniseries.

Or, for that matter, an up-to-the-minute pomo marketing endeavor. Biophilia is as detached from its identity as Bjork is from hers. It isn’t really an album so much as a nexus for related products, including a series of apps for every song and a range of multimedia live shows some of which, apparently, include National Geographic imagery. Still, as I lack the funds, the technology, and the interest to pursue the album through its metastasizing iterations, I’m happy that my brain has instead decided to attach the soundtrack to my own hazy memories of creepily perfect nature specials past. I hate to admit it, but Bjork as Bjork was beginning to get a little boring. Bjork as mushroom with David Attenborough narration, though, is a thought to cheer every phylum.