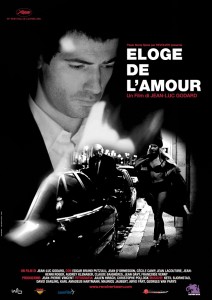

Eloge de L’Amour, as the title suggests, has the feel or tone of a eulogy: a meditation on cinema, love and art. The story is completely non-linear and incredibly dense. Each scene, every image in fact, contains so much information that it becomes impossible to decode even on several viewings and through different (French and Scottish) cultural positions.

Perhaps the plot is simply a vehicle here for Godard’s concerns that the corporate capitalist monster will destroy cinema, destroy humankind and destroy love.

The film is beautifully shot but deliberately difficult to follow: the first half is filmed in lush black and white and supposedly concerns a project about the four phases of love (meeting, attraction, separation, reconciliation) while the second part takes place earlier and is shot in saturated digital colour. But the digital experimentation of video juxtaposed with the nostalgic black and white film is just one of many filmic ideas explored in metalevels. In the film’s hermetic inner world, Godard asks a lot of the viewer: referring to American cinema, to his own oeuvre and to history and to all stories and their possibilities.

Released in 2001, the film is aggressively anti-American (as if the corporations and the USA were conflated), accusatory, and even suggests that Americans have no past of their own, no history. Possibly Godard is referring to mythologizing and to re-examining the past or reinventing the self. Certainly America encompasses both North and South, and taken separately the points the characters make seem trivial, even petty, particularly the attack on Steven Spielberg for Schindler’s List.

The subjects Godard addresses: the Holocaust, the French resistance, corporate control, are still raw, but there is a deliberate distancing: if clarity surfaces, then narratives are overlaid, obscuring, obfuscating, thus making immediate comprehension impossible yet deepening absorption.

There can be no doubting Godard’s cinematic mastery and technique: this is a hauntingly beautiful film. Yet the actors do not act like actors, they seem different even from real people and the narrative fragments, the characters mutter philosophical aphorisms such as: “there is no death… when it comes there is always a sense of self… moi… moi.” Connecting textual elements seem out of sequence, out of phase and out of synch and blank, black screens appear at random.

It sounds convoluted, and indeed it is, but the soundtrack is filled with sweet piano and strings and somehow through multilayered mumblings, Eloge de L’Amour elicits powerful emotions and the effect is overwhelming.

John Chalmers is one-half of the duo known as “Metaphrog,” along with Sandra Marrs.

______________

The index to the Godard roundtable is here.

“Released in 2001, the film is aggressively anti-American”

Is strongly disliking America’s cultural hegemony really “anti-American?” According to IMDB, it was released on October 16, 2001. Is it really “anti-american” to say that many people in this country have a poor grasp of history? Language of course is really important in Godard’s works. I think it’s be better to choose a more precise term or phrase.

There was a brief scene in one of his post-1980 films where a female American plane passenger was messily gorging herself on food. Her inclusion was obviously meant as short-hand for Americans. I thought that was overly cartoonish and more than a little unfair on JLG’s part. But it’s still debatable in the end.

I haven’t seen this since it was released, but based on this really negative review, it doesn’t seem outrageous to claim Americans are part of his critique of America (e.g., they have no “memory of themselves”).

Thank you for your interesting comments. The way Godard refers to America, obliquely and persistently throughout the film, through his characters, seemed aggressive (the facile argument that America includes also the geography of both North and South is repeated almost like a refrain), but sadly, an equally large number of Europeans over-eat (France’s gluttony is depicted in Marco Ferreri’s film La Grande Bouffe, for example) and watch TV without a great knowledge of their own history. So, in consideration, this wasn’t something we felt was particularly anti-American about the film when we wrote our thoughts. The date of release is extremely important as it adds context to the idea of a cultural hegemony and the sense of zeitgeist. In a sense the characters mull over ideas that were in the air at the time and weave these ideas with the memories of atrocities of World War II, so the sense of History versus non-History is thus amplified. However, it was simply the attack on American presumptuousness that seemed aggressive and perhaps the film better addresses the problems of colonial imperialism (of which the European countries are equally guilty), as well as individual solipsism.

I do agree that the charge of cultural appropriation was too facile on JLG’s part for the reasons you’ve stated.

The problem with using “anti-American” as a term is that it’s too general; it’s too reflexive. For the most part JLG objects to specific negative cultural habits. So rather than directly addressing these, most of his detractors wind up responding with a ever-more generic charge of “anti-American.”

I’ve never read Ed Gonzalez’s reviews before. Could be wrong, but from reading it I don’t get the impression that he saw the film more than once. Certainly that could be said of many of the reviewers of his movies. Besides, what’s so petulant about sticking it to Spielberg? “Schindler’s List” is a pretty weak movie.

““Schindler’s List” is a pretty weak movie.”

I think that’s putting it mildly.

For me, Spielberg is great filmmaker with some bad ideological choices, but I’m not big on Maoists in sports cars, either. Munich, AI, Minority Report have plenty to critically engage with. At least, I’d rather watch any of those again than In Praise of Love. Actually, I’d rather watch Schindler’s List, too. I haven’t seen it in over a decade, but I remember it being an impressive formal feat if nothing else. Spielberg deserves to be critically attacked, but he deserves more than flimsy dismissals (which has started to turn around a bit with the recent celebration of AI). I’ve kind of changed my mind about him over the years. Are his films so much intellectually weaker than those of Hawks or Ray or any other New Wave favorite from back in the 50s? I’m not so sure. On the other hand, Armond White’s rabid defenses of Spielberg are mostly ridiculous.

I pretty much dislike most Spielberg I’ve seen (I saw Jaws recently, and it’s crap, for example.) Shcindler’s LIst is especially horrible though. Smug, feel-good pap about the Holocaust — I think that’s fairly unforgivable.

The first Indiana Jones movie is pretty good though.

Noah – I’m not sure why you didn’t like “Jaws,” as I think it’s one of the best films Spielberg has directed. The other films he directed that I really liked are “Raiders of the Lost Ark” and “Saving Private Ryan.” I guess I’d also throw in “Jurassic Park,” but that could be because I have a soft spot for dinosaurs.

As far as Spielberg-directed films I really disliked, I’d include “1941,” “Hook,” and “Indiana Jones and the Kindom of the Crystal Skull.” I’m also tempted to throw “War of the Worlds” in there as well.

The rest of Spielberg-directed films I’d say fall somewhere inbetween.

Russ, I don’t want my slashers bogged down in sincere human emotion and idiotic becoming-a-man melodrama crap. Slashers are for Freudian castration panic, damn it, and I would like to keep them that way.

Let’s not forget Duel… and also the Columbo episode Spielberg cut his teeth on: Murder by the Book. Just one more thing…

Noah — Ha! Well, I thought Robert Shaw knocked it out of the park with his portrayal of the character Quint.

At first I was going to say that Jaws IS about castration panic but then I realized I was thinking of After Hours:

http://www.princeton.edu/~ddunham/cinema/after%20hours.jpg

Anyway I saw Jaws on the big screen a little over a year ago and loved it. Never really cared for it before that, not sure what brought on the change. Maybe it was the mix of wonderful natural lighting and sharks eating people. (the sequels had plenty of the latter, none of the former). I know the spectacle of painted light is pretty much the sole reason for Close Encounters to even exist and it’s more than enough of a reason for me. I guess that and paying tribute to Truffaut. That’s my favorite Spielberg by far.

The Indiana Jones movies were childhood favorites but I’m a little bit wary to go back to them after seeing the horrible 4th one.

The rest of his movies are either wildly uneven (E.T., Minority Report, Schindler’s List, A.I.), death by artificial saccharine (Hook, War of the Worlds), or I haven’t seen (Schindler’s List, Amistad).

I don’t love him by a long shot, but I like his best movies more than anything I’ve seen by Godard or Bunuel.

Oh yeah, and Shaw/Quint! Thanks for the reminder Russ, he stole the movie.

with the “uneven” ones that should be Saving Private Ryan, Spielberg’s other “serious” movie in place of Schindler’s List, which I haven’t seen.

I think when you take it all together, including things like “Jurrasic Park,” his work is pretty much a mixed bag. I did like “Sugarland Express,” A nice little pinball chase movie. The somewhat downbeat ending gives just the right amount of balance to the usual overly-sunny narrative. What Spielberg has been missing in his career is a sardonic John Lennon to his sacharrine Paul McCartney.

But then again, most directors careers when looked at in aggregate are mixed bags.

I think most strong directors–and actors, too–have a golden period of about 4 to 8 years where everything comes together for them in a way that makes their work really fresh and exciting. After that, their work hits a plateau. While they sometimes come through with something pretty remarkable, most of what you get is just skillful mediocrity. Spielberg’s major period as a director was between 1975 and 1982: Jaws through E.T. Granted, 1941 was a big misfire, but it’s a pretty amazing film nonetheless. As bad as it is, it isn’t mediocre.

Spielberg aside, I tend to agree with Anne Wiazemsky that Godard had a second plateau period. Dziga Vartov went beyond mediocre into actively bad — but Passion is really extraordinary, and he does a lot of wonderful things after that.

I’d rather poke my eyes out with a stick than see another horrendous Spielberg film, after the relentless torture that was AI, never mind the rest of what he’s done, tinkly soundtracks and all. At any rate, comparing him with Godard is the utmost of pointlessness.

There are the Godards who buck that trend. Altman and Lynch are also examples. With those artists, they tend to have their golden period, then they wander in the aesthetic wilderness for a while, and then they have a longer silver period, the high points of which sometimes eclipse some of the better work of the golden period. An example would be Lynch and Mulholland Dr.

I’ll have to take your word for it with Godard, though. The only three post-1980 films of his I’ve seen are First Name: Carmen, Hail, Mary!, and Notre Musique. I thought the first two were terrible, and I fell asleep about halfway through the third. I don’t remember much of what I stayed awake for, but it didn’t impress me enough to catch up on what I missed.

I think I remember somebody involved in this roundtable really liked Notre Musique…maybe that person is reading this and will say so and why. I want to but have not yet seen that one…

I liked Notre Musique a lot more than Eloge de l’amour (which I don’t think I ever finished), though I’ve only seen both one time. Been meaning to rewatch the former to see if my good impression of it stands up. I am a sucker for structured narratives like that (it’s in three pretty distinct parts, as kind of heaven/hell/purgatory).

Caro, the person who mentioned “Notre Musique” was you. Haven’t seen it in years, but had no trouble getting immersed in it just now while taking a brief peek at the segments on youtube.

Oh, I meant someone participating in the roundtable mentioned it when we were talking about the films to write about. Not something in comments…the comment I’m referencing there is not from anybody participating in the roundtable. My objections to people saying Godard is “self-important and boring” are akin to your objections about “anti-American,” in that film or any others…

I can’t say much about Godard’s post 60s films because the only one I’ve seen was Lear – a long time ago.

As for the 4-8 year golden ages thesis, I don’t know that I’d agree overall. Certainly that seems to be the critical consensus, which perhaps even colors what things get made and how careers develop, but on a case-by-case basis I think the best I can say is some do get lazy and some don’t. And some might just get lucky or unlucky.

I really do think Altman was pretty consistently trying new things throughout his career (Tanner, Vincent and Theo, The Company, and I would never have guessed he even had Gosford Park in him from his early work), but then we should also note that he was already in his mid-40s and had a career in television before his “golden age” even started. And it’s not like he didn’t have duds even in the 70s (Quintet) and some of his best films of the period are still little-watched or appreciated, like Brewster McCloud.

Another one who was no spring chicken in his “prime” is Peter Greenaway, and how much of his success in the 80s is an anomaly of coinciding funding, finding an audience for his peculiar vision and great collaborators like Michael Nyman and Sacha Vierny? The death of Vierny aside I don’t think his work has noticeably declined or gotten lazy but it does seem like it’s harder for him to get stuff made since The Cook, the Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (probably my least-favorite of his “major” films, but his most popular).

What about Melville?

Welles to me seems to defy any strong pattern of inspiration, then decline in that he seems to have done his best work (or at least the most interesting to my eyes — such as Othello and Four Men on a Raft) by screwing himself over and then trying to find creative ways to overcome (often) self-made impossibilities — a pattern that spanned his whole career.

I think a lot of ones who do peter out like that may have just been somewhat of hacks to begin with who just lucked into a cultural/zeitgeist sweet spot and the right collaborators/ideas by the alignment of the stars, such as John Frankenheimer, Boorman, maybe on the art-house side Ken Russel…

I’m still not sure what to make of Godard though, I need to see more and re-watch what I have seen.

I don’t know if age is a determining factor. I’m sure there are several filmmakers who didn’t come into their own until they were well into middle age or later. I’m also sure there are plenty of exceptions to the rule. I think it’s a pretty good rule, though

I also don’t think creative complacency is necessarily about laziness. Artistic chance-taking is borne of necessity as much as anything else. A lot of artists just get to the point where they’re in enough command of their craft that they don’t need to guess a solution to a creative problem anymore; they know the tried-and-true approaches and fall back on them. Unfortunately it’s the guesses into the unknown that made them exciting to watch in the first place.

As far as Altman is concerned, I’d say his golden period ended with 3 Women, and his silver period began with Vincent and Theo. He made a lot of bad movies in his golden period, though. Pauline Kael liked to say Altman’s films during the ’70s were one-on and on-off: a good one would be followed by a bad one and so on. She’d pan Images or whatever and then say she could hardly wait for his next film.

I don’t think the rule is applicable just to hack-oriented directors. Godard’s golden period was 1960 to 1967. Antonioni’s was 1960 to 1966. Fellini’s was 1954 to 1963 (OK: 9 years there). Bertolucci’s was 1964 to 1972. Truffaut’s was 1959-1962. Bergman was operating at a really high level between roughly ’53 and ’58. He was then in a rut until 1966, when he became involved with Liv Ullmann and began making really interesting films again, starting with Persona. Among the Americans, Coppola’s golden period was 1972-1979, Scorsese’s was 1973 to 1980, and Altman’s was 1970 to 1977.

Post-1980 Godard probably takes years to warm up to. That was certainly the case on my part. His approach is so idiosyncratic that even aficionados of Tarkovsky & Dreyer might be repelled by it.

As far as longevity goes, in Godard’s case his approach to the essay film probably accounts for it. If he had chosen to continue standard narrative films I doubt he would have been able to avoid repeating himself like just about everyone else. It’s like what Noah said some months back about the comics world needing creators who were into theory. Not that Godard isn’t instinctual in the way he puts thing together, but he certainly experiments whether in studio or on the set with audio, imagery and of course text. Not to turn this into a sickening hagiography, but he’s cinema’s real “atom-smasher.” But it’s not simply smashing narrative bits and being pleased at how they lie but what he does with those bits and how he puts them together that makes him so interesting and worthwhile.

I’m not an expert at all, but from my limited exposure, I think I’d agree that Godard is self-important (often), boring (not infrequently), and anti-American. But I don’t think any of those things is a deadly critique; Spielberg isn’t self-important, boring, or anti-American, but I like him a lot less than I like Godard.

Like with Robert, I don’t agree that laziness is a factor in any filmmaker’s decline. One could never call Coppola “lazy.” Filmmaking isn’t like writing or painting. There’s a tremendous physical toll in trying to overcome all the usual obstacles in getting something made.

But in other ways, though it is like other forms. Most good artists probably have one or two great ideas before the decline sets in. It’s not any different in that regard with film. But of course there’s always exceptions.

Yes, there are exceptions to the “director’s rule” — Clint Eastwood is a good example of that, I think.

Comics-wise, Kirby surpassed all of his earlier work when he was at Marvel during the 1960s. His best work probably occurred from 1965-1967, when Kirby was pushing 50 years old.

I refuse to admit that Scorcese had a golden period. Or Coppola. It’s dross all the way down.

Are Coppola, Scorcese, and Altman considered the three most important American directors? I’m really going to be depressed if that’s the case….

I think the comics-needing-people-who-are-into-theory is more Caro’s thing than mine? I mean, I could have said it, but Caro’s a lot more eloquent on that topic than I am.

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

I refuse to admit that Scorcese had a golden period. Or Coppola. It’s dross all the way down.

———————–

Umph. Why am I not surprised? (Is Domingos-itis catching?)

As for the lack of respect given Spielberg in many critical quarters, I can understand that; as with Toth, one sees technical brilliance and utter mastery regularly employed on stories which are less than substantial.

Spielberg’s oeuvre is also all over the place, unlike, say, Hitchcock’s, with The Terminal and Always joining FX-heavy spectacles like CE3K and E.T. Making it more difficult to discern a directorial worldview or recurring obsessions.

Have not yet seen Schindler’s List or Saving Private Ryan (aside from the harrowing D-Day sequence), but his “serious” fare like Munich, The color Purple, and Amistad end up being unsatisfying in ways that Jurassic Park or Minority Report do not.

While the latter utterly succeed at achieving their humbler goals as entertainments/thrillers, with “serious” Spielberg his intellectual limits are more evident; his perceptions either obvious or muddled. (Not that he’s a dummy, but…)

(It thoroughly rankled in “Amistad” how the abolitionists were shown as cynically willing to let the slaves involved serve as victims to advance their cause; how, aside from their initial violent uprising, the slaves were then depicted as utterly dependent on the benevolence of sympathetic whites to gain their freedom. A noxious slime like George Will praising — in the conservative ideological public exaltation of the individual over the group — the scene in the movie when ex-President John Quincy Adams makes a courtroom speech and wins their case as proving how all it takes is one person to bring about freedom or finish oppression, like Rosa Parks did by refusing to sit in the back of the bus, thereby bringing segregation to an end. [What gets left out of popular accounts was that, rather than a spontaneous gesture of defiance by an isolated black woman, Parks was part of a group, an involved civil-rights activist, and the decision to sit in the white section of the bus was carefully thought out by them and planned…])

In comparison, Alan Moore and his art-partners have done works like Watchmen and From Hell which are not only absolutely technically successful, but laden with ideas and much food for thought, perfectly realized within the body of gripping entertainments.

With Spielberg, what I most appreciate are box-office “runts of the litter” like Empire of the Sun and A.I. Artificial Intelligence.

The former featuring one sequence displaying awe-inspiring directorial powers; the young boy (Christian Bale!), coming back to his parents’ house after the Japanese invasion of Shanghai, sees the bare footprints of his mother on the bathroom floor. Their pattern clearly communicating, with harrowing editing, camera movement, and music, that the invaders had come upon her there, she’d tried to escape, was captured and assaulted.

And as for A.I., what a fascinating blend of the talents of friends whose directorial viewpoint could not be more different. The story like an old, un-Disneyfied fairy tale: melancholy in its ending, and with a far-from-idealized young protagonist. (The scene where he comes upon batches of identical robotic copies of himself and, freaked at discovering he’s not a unique individual, violently smashes the little robot boys to bits surely far from audience-pleasing.)

I was a little hasty in dismissing all of Coppola…I like Dracula, and Apocalypse Now (as far as I remember the latter.)

What do you have against Altman? He’s right up there. Nashville, M*A*S*H, etc. His late period is not too bad either, with low-key charmers like “The Company.”

“Apocalypse Now” is great, but I despised his “Dracula.” All sizzle, no steak with that one.

Wow, I’m behind. I’m interested in Noah’s question about the most important American filmmakers. If I had to pick the most important filmmakers period, I’d pick Godard and Cocteau, with Tarkovsky, Eisenstein and Orson Welles tussling for that third spot. So for me, “important” definitely means people who have pushed against the conversation about film, consistently risking failure in order to comment on what they and others and film in general were doing. If I had to limit that list to Americans, I’d pick Lynch, Welles, and Robert Frank.

But there’s also a list where successful narrative and solid craft matter more, where the quality of the end product is weighted heavily and the challenge to the conversation less so. For that list, I’d put Fritz Lang, Ingmar Bergman, and Billy Wilder for the best period — and I’d pick Wilder (if you let me count him as American), Altman, and Terence Malick for the America set. If I had to pick someone other than Wilder, it might be Woody Allen.

But I don’t know — it seems like a very idiosyncratic thing, to make such a list…

————————-

steven samuels says:

“Apocalypse Now” is great, but I despised his “Dracula.” All sizzle, no steak with that one.

————————–

…Just stake! (Sorry, couldn’t resist…)

We thought Coppola’s Dracula was beautifully made and exciting in many ways; though sure, Persona it’s not…

I recall reading that there two kinds of writers; those who repeatedly focus on subjects that are personally meaningful (when they aren’t outright obsessions), and those who are storytellers, with a wide range of subjects.

With filmmakers, those who are highly productive usually end up with oeuvres that are all over the place; united only by their directorial talent and expertise.

Like Spielberg, or Howard Hawks (“…versatile as a director, filming comedies, dramas, gangster films, science fiction, film noir, and Westerns”: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Howard_Hawks ) Coppola’s gone from Peggy Sue Got Married to The Godfather II; with, along he way, remarkable oddities like his adaptation of S.E. Hinton’s Rumble Fish, a knockout in every way…

Noah–

I’d say Altman, Coppola, and Scorsese are considered the three most important of the Hollywood renaissance period between ’67 and ’77 or so.

Caro–

How would you rate Renoir and Kurosawa?

Dracula’s great because it is all surface. Coppola has nothing interesting to say for the most part. Dracula is shallow, brainless eye-candy. That’s what he’s suited for.

I liked McCabe and Mrs. Miller. Mash not so much. Altman is really glib for the most part, at least the films I’ve seen. He’s not horrible or anything, but to think of him as a major filmmaker is kind of depressing.

For American filmmakers, I really love Jack HIll. Quentin Tarantino too, damn it. Cronenberg and the Coen Brothers are way more interesting to me than Scorcese or Coppola (though they’ve kind of fallen off a cliff recently….) I like David Lynch too….

I’d have put Cronenberg on my American list, Noah, if he weren’t actually Canadian. ;)

Tarantino and the Coen brothers are postmodernity’s Frank Capras (as is Spielberg for slightly before.)

I don’t really like ANYTHING from that Hollywood Renaissance period, except maybe Thieves like Us. With Scorsese and Coppola, it’s mostly the narrowness of the subject matter that puts me off — sort of the same problem I have with a lot of comics. They are also very male-oriented filmmakers — neither has a relationship with an actress like Altman’s with Duvall. And that focus on male stories and actors diminishes them, to me. (Although I have had the pleasure of meeting Martin Scorsese and he is a delightful person, who was at the time I met him deeply concerned about an ill wife, so I really don’t mean any ill by that statement.) I don’t feel they have the range that Altman does, which is why, given the value of that period, I pick Altman. I think Polanski is more important than all of them though — Chinatown trumps them all. But he’s not American.

I value Ozu more than Kurosawa, Robert. But I also like Renoir vastly more than Truffaut. Ozu and Renoir would definitely be in a top 10…

Caro! Someday we must gather together and watch Chinatown and Ozu. One of my favorite movies and one of my favorite directors.

The comparison to Frank Capra is interesting. I don’t think it’s quite on target, but there’s something there. Maybe a less ambivalent relationship to genre than in some of the other filmmakers we’re talking about? I don’t see that as a demerit, but it’s kind of an interesting fissure.

Ozu is extraordinary. Good Morning is probably my favorite film of the 1950s. I think it’s absolutely brilliant.

My husband buys my Tarantino/Capra comparison but says I should use Sirk for the Coens. Which I can buy. What I was getting at is that in both cases the appeal to/mirror of the zeitgeist is dominant (although the zeitgeist of the 40s-50s and today is almost diametrically opposed). Those films will date even more than the ’70s Hollywood renaissance ones, which is saying something.

I might put Lumet above Altman, maybe. Fail-Safe is a masterpiece, but it’s also early. The Hollywood Renaissance was so influential that it’s hard not to put a director from then on the list of important Americans — but the Americans just weren’t the ones doing the best work in that period.

I think a less ambivalent relationship to genre is part of it, but I think, ultimately, it has more to do with zeitgeist and audience. Capra gets a lot of shit but he was a really good craftsman who really understood his audience, making films that really tapped into his historical moment and that meant a lot to people in the time he was making them. He made a lot of wartime documentaries too. He was solid, and popular.

But I think his films, and Sirk’s (although I like Sirk), date in a slightly sour way, in a way that, say, the films of Powell and Pressberger do not. Black Narcissus is the film Douglas Sirk spent his career trying to make and missing…I think he couldn’t see his way out of the genre to quite the same extent, and that’s limiting. I think you can have perspective on genre without actually being ambivalent about it…

I think making predictions about what will date and what won’t is a way to get yourself in trouble. We’ll just have to wait and see!

My top three are Orson Welles, Buster Keaton and Kurosawa.

Tod Browning, Leni Riefenstahl and Andrei Tarkovsky would probably make the top ten too. (Haven’s seen enough Eisenstein).

My “maybes” include Lynch, Greenaway, Cronenberg, Gillian Armstrong, Tsui Hark, Brian De Palma, Robert Altman, Stanley Kubrick, Nagisa Oshima, and Roman Polanski.

It’s easier for me to list films than directors. My favorite 20 or so, although I’m not making a canonicity argument for any of them:

The Fabulous Baker Boys, Pandora’s Box, City Lights, The Rules of the Game, Brief Encounter, L’avventura, Weekend, The Conformist, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Godfather/The Godfather, Part II, Chinatown, Jaws, Nashville, Annie Hall, Tootsie, Ran, Carlito’s Way, Before Sunrise/Before Sunset, Out of Sight, Mulholland Dr.

Preferred directors career-wise, looking at this list, are Renoir, Antonioni, Godard, Altman, and De Palma. The directors who I think are doing the most interesting work right now are Cuarón, Iñarittu, and Assayas. I suppose I should include Cristian Mungiu and Jason Reitman with them, although with those two it’s largely on the basis of single films.

Caro–

There’s a big chasm between us when it comes to movies. The Hollywood Renaissance is very much the foundation of my taste. I agree with you that it’s very male-centric, though.

There’s a big chasm between our views of Fail-Safe, too. I pretty much agree with the view that it’s what Dr. Strangelove would have been if Kubrick had decided to play the subject matter straight, and it illustrates just how much weaker the straight approach is. Lumet’s version, though, is better than the remake George Clooney and Stephen Frears did for TV a few years back. My favorite Lumet films are Dog Day Afternoon and 12 Angry Men.

These guys I always feel like watching: Yasuzo Masumura, Shohei Imamura (my favorite Japanese), Akira Kurosawa, Fritz Lang (my favorite German), Billy Wilder, Mario Bava, Federico Fellini (my favorite Italian), Henri-Georges Clouzot (my favorite Frenchman), Jacque Tati, Alfred Hitchcock (my favorite Brit), Joseph Losey (my favorite HUAC escapee), Stanley Kubrick (my favorite American), Anthony Mann and David Lynch.

I really hate Lumet’s liberal claptrap, but The Fugitive Kind features Brando in one of his craziest performances.

Good lord, Robert. Jaws? Tootsie? The Godfather? Say it ain’t so!

Of course, The Thing would be on my list. And possibly Swinging Cheerleaders. And maybe I Spit on Your Grave. So nobody’s probably looking for my opinion anyway….

Oh…just thinking about 12 Angry Men. I love that movie for the seamless patness of its liberal claptrap. It reaches a an apogy of smugness that is kind of sublime.

Scorsese is far from being one of my favorite film directors, but I like some of his films: _The Age of Innocence_, for instance… (My favorite Scorsese films are his journeys through American and Italian films.) My favorite American filmmakers are John Cassavetes and John Ford. I could also include Erich von Stroheim if he can be considered an American director.

I’m surprised that no one mentioned my favorite film directors so far (Ozu excepted): Kenji Mizoguchi, Robert Bresson, Roberto Rossellini.

I don’t take the politics of 12 Angry Men very seriously. I just think it’s a terrifically paced single-set melodrama. I really enjoy the rhythm of it. I’m not big on Lumet’s films in general.

As for my “say-it-ain’t-so” favorites, I think Jaws is a brilliantly artful suspense film. It’s just a bible of effective cinematic storytelling. Tootsie is a terrifically well-written, -directed, and -acted satirical farce about actors. I tend to ignore the mushy gender tripe. The Godfather is probably the best film to ever come out of Hollywood. The Fabulous Baker Boys is my personal favorite, but The Godfather is the one for which I’d make the biggest canonicity argument. Noah, I’d be curious to find out what you dislike about it.

It’s been a long time since I’ve seen the Godfather, since I really didn’t like it. But mostly I found its enthusiastic conflation of violence, ethnicity, and authenticity to be both repellent and bone-headed.

Is it the case that you’re more swayed by technical virtuosity in film than comics, Robert? You tend to resist formal arguments for worth in comics (I think?), but the case for both Jaws and Tootsie seems largely predicated on formal accomplishment. Am I reading that right?

The rhythm of 12 Angry Men is absolutely the reason to love that film…but I think it merges with its politics, and is kind of inseparable from them. It’s an incredibly pat view of the world and of the place of American justice within it. It’s so banally satisfying and satisfyingly banal….

Anyway, to get vaguely back on topic maybe…any love in here for Spike Lee? And am I crazy for thinking his films are maybe more Godard-like than most anyone we’ve mentioned? He’s obsessed with both filmic artificiality and radical politics and the connections between the two in a way that seems pretty Godardian (Godardic?) Though Lee’s a lot more committed to the radical politics and a lot less to the filmic artificiality, whereas Godard seems like he’s maybe the other way round…

There aren’t many comics creators with the storytelling virtuosity of Spielberg at his best. You show me comics with technique at that level and I’ll praise them, too.

Tootsie is more than just technique. It does a hilarious job of lampooning the monomaniacs, neurotics, and flakes that are a fixture of any struggling artist scene. It isn’t quite as good at nailing the cynics, creeps, and barnacles who are frequently the successes, but it does a pretty fair job with them, too.

Movies are a pretty superficial art form. Like music, they’re very dependent on technique and style for their effectiveness. Both essentially demand a passive audience, and that requires the artist to create an immersive experience. Movies are not the place to find profundity; the viewer has to absorb information at too rapid a pace for them to have the kind of narrative density and sophistication one finds in good novels.

Comics are meant to be read, like prose and poetry are. They demand an active engagement on the part of the reader, and in that context, brilliant technique just isn’t enough. Technique for technique’s sake makes for a very thin reading experience. To be worthwhile, they need the richness that good fiction has.

Ha! I don’t know how much of that I agree with, but I love that you’re effectively launching deadly insults at both comics and film. That warms my heart.

I just don’t see Spielberg’s storytelling abilities as so technically accomplished, I guess. Jaws certainly fits together well enough, but mostly because it’s hackneyed. Not unlike 12 Angry Men, I guess; there’s the satisfying, tedious click of ideology meshing and men triumphing over nature and civilization to become manly men.

I just feel like compared to something like Stephen Crane’s “The Open Boat,” Jaws kind of folds up under its own complacency. “The Open Boat” is extremely well constructed; it has an inevitable rhythm. But that rhythm serves not to comfort — to show that narrative is on your side. Rather, it pits narrative against your side; the sweep of the plot, or of time, is an arbitrary force that doesn’t care about you or your boat.

I know it’s kind of mean to sic Crane on Spielberg…II just feel like, in film as in comics, I can’t abstract the formal skill out from the content. Jaws is a fairly banal tale of a fairly banal hero triumphing over standard-issue adversity. To me, that very much interferes with my formal enjoyment of the film.

As far as empty-headed action flicks go, I’d much prefer any of the early Bonds, or, for that matter, Prince of Persia, which nicely erases itself in an explicit acknowledgment of its own meaninglessness.

Film isn’t prose. Film is better at creating a rich immersive experience for the audience, while prose is better at creating a rich contemplative experience.

Taken strictly as a story, Jaws is banal. But the telling is extraordinary; Spielberg orchestrates conceptual imagery, staging, photography, acting, editing, scoring–all of which is generally excellent–into a brilliantly imaginative and artful whole. It’s similar to a musician–say, Miles Davis–taking a banal pop tune and transforming it through the arrangements and performance. It’s entirely superficial, but that superficiality is an exceptionally rich one, and that richness is worthy of applause.

Prose and comics can’t get by with stories as banal as the one in Jaws because they can’t create immersive experiences that have the immediacy and intensity of what you can find in film. They need to provide a richer contemplative experience to be worthwhile.

I’m not launching a deadly insult against film. I’m just saying that what it’s good at is different than what prose is good at. I’m not insulting comics, either. Comics creators, on the other hand…well, they deserve the insults because they need to make better use of the medium for their material to be worthwhile. They need to provide the richer contemplative experiences of prose and forget about trying to compete with the immersive capacities of film.

Isn’t the real fear in Jaws commerce, not nature? The shark is just doing what it does. It’s in the interest of capital that the people are put in danger. Man struggles with bureaucracy — many die, the man lives, and the shark is sacrificed so that his home is safe for tourists once again. Jaws is a tragic victim.

Anyway, the flow of action in Spielberg films is second to none. He knows how to keep his audience on the edge of their seats. He has a cinematic eye, much like Hitchcock’s.

By the way, please point me to an action film before Jaws that makes such sustained and varied use of metonymic storytelling–both through images and music–or utilizes movement within the film frame as effectively, or is more impressively edited. I’d like to see it.

Spielberg’s style was considered rather radical at the time. Older directors were reportedly very taken aback by it. Hitchcock said that Spielberg was the first director he’d seen who didn’t think in terms of the proscenium arch. Spielberg conceived his shots in terms of graphics and movement; he didn’t bother with theater-style staging. His work was quite innovative.

Yeah…I find Citizen Kane pretty boring too. And a lot of Hitchcock does little for me. I don’t really buy that film needs content less because it’s immersive. Or at least, it really doesn’t work that way for me. The fact that a director is formally innovative with a trite piece of piffle — I just viscerally don’t care. Maybe I’m not enough of a film buff?

Jazz and pop tunes..Miles Davis can be fairly blah too, is the truth. But what Coltrane does with My Favorite Things is more like Godard chopping up a crime story in Breathless than like Spielberg building a better shark-trap in Jaws. Davis and Coltrane were snooty avant-garde poseurs, not people-pleasing genre hacks.

Sinatra would maybe be a better analogy for Spielberg? And yeah…there I think I’d agree that music is something where content is often less important than immersive experience. But I also find the anatomizing of love in jazz pop standards significantly less bone headed than the Jaws script.

Charles, it’s always fun in horror to read the film from the perspective of the monster. I don’t think Jaws is especially interested in, or effective at, pushing that reversal though. It’s not Night of the Living Dead or Freaks, to name just two examples. It’s an empty headed fight against the monster movie. If you can find sympathy for the shark, that’s because you’re smart, not because Spielberg is.

Commerce is obviously bad…but it’s bad because it doesn’t respect nature red in tooth and claw. It’s like the weak-willed, effete city assholes in Call of the Wild; they do not understand the primal battle, doncha know. The whole thing is in the interest of letting our hero embrace his inner aqua-beast.

Jack London is enjoyably demented, though; he really actually thinks that city people deserve to die for their weakness, which is maybe why he’s able to tell the story from the perspective of the animal the way Charles half-imagines Spielberg telling it.

I think I even like the Old Man and the Sea better than Jaws, and I really don’t like Hemingway much.

—————————-

Robert Stanley Martin says:

There aren’t many comics creators with the storytelling virtuosity of Spielberg at his best. You show me comics with technique at that level and I’ll praise them, too.

Tootsie is more than just technique…

—————————–

Um… [Sound of knives being sharpened]

I’d certainly give kudos to Spielberg’s technical ability, ways to fluidly synthesize and employ the countless cinematic moves he’s absorbed and mastered. Why, the man must have celluloid running in his veins!

And yet, after equating “technique” with “storytelling virtuosity,” with that “Tootsie is more than just technique” you — in effect — note that amazing directorial prowess in the service of empty/not-very-deep stories is but a very limited success.

I’m reminded of Pauline Kael’s critique of the 007 flick On Her Majesty’s Secret Service: “On the one hand, it isn’t worth doing, but it sure has been done brilliantly.”

———————————

Movies are a pretty superficial art form. Like music, they’re very dependent on technique and style for their effectiveness. Both essentially demand a passive audience, and that requires the artist to create an immersive experience. Movies are not the place to find profundity; the viewer has to absorb information at too rapid a pace for them to have the kind of narrative density and sophistication one finds in good novels.

———————————–

Film certainly has its limitations; yet to say “they’re very dependent on technique and style for their effectiveness” leaves out (as predictably usual, alas) the contributions of the screenwriters; that a story with depth, complexity and substance is also necessary for a movie to be more than an expertly crafted entertainment.

And, gee, we may as well likewise condescend to Shakespeare, Strindberg, Ibsen, Chekhov for also working in “a pretty superficial art form”; argue that “Plays are not the place to find profundity; the viewer has to absorb information at too rapid a pace for them to have the kind of narrative density and sophistication one finds in good novels.”

————————————

To be worthwhile, [comics] need the richness that good fiction has.

————————————

…Which in film is considered an irrelevant and unimportant factor by some. Where is our Robert Stanley Martin, and what have you done with him?

(The Writers Guild’s 101 Greatest Screenplays: http://www.simplyscripts.com/wga_top_101_scripts.html )

————————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Yeah…I find Citizen Kane pretty boring too.

————————————–

Of all the Noah Berlatskys in the world, you’re the Noah Berlatskyest!

————————————-

The fact that a director is formally innovative with a trite piece of piffle — I just viscerally don’t care. Maybe I’m not enough of a film buff?

…I don’t think Jaws is especially interested in, or effective at, pushing that reversal though. It’s not Night of the Living Dead or Freaks, to name just two examples. It’s an empty headed fight against the monster movie. If you can find sympathy for the shark, that’s because you’re smart, not because Spielberg is.

————————————–

Yeah, I’m pretty amazed to see Jaws — for all its effective moments — being so praised. (And absolutely agree about the brilliance of the infinitely superior NOTLD and Freaks.)

If being a film buff means thinking “the story is utterly irrelevant; technique is all!” then Heaven help us.

But then look how revered Toth is, when virtually every script he worked from made the most commercially claptrappy screenplay Spielberg helmed look like King Lear…

BTW, if you’ve read the utterly abysmal Benchley novel, my sympathy; this was one of the rare cases where the film was much superior to the source. (Another being The Godfather, as widely noted.)

Noah, all films date! It’s just a question of whether they’ll date sourly or charmingly. And, historically, that’s often boiled down to how seriously they took the elements they got from the zeitgeist. Capra and Sirk took the surface tensions of the ’50s very seriously, and they date sour. I think both Fail-Safe and Dr Strangelove did not take the surface tensions of the ’60s seriously — they were able to grapple with why they were tense, not just that they were. And they’ve dated much less. Robert, I don’t think I have to choose between the two, really, do I? I mean, by far and away, and then a small piece more, my favorite film in that genre is Alphaville…as I’ll tell you next week.

Tarantino really REALLY digs his schtick with pastiche repurposed ’70s action films — that’s about as pomo zeitgeist as it gets. I’m ok betting that it will date like Capra. And that some people will like it anyway…but what those films will say about our now in 50 years, I’m more than happy disavowing in advance.

Caro, if by “seriously” you mean he thinks about them carefully and thoughtfully, then I agree. But I don’t think that will make his movies irrelevant. But, like I said, we’ll find out if we live long enough!

I don’t really like Dr. Strangelove any more than It’s a Wonderful LIfe; they both seem pretty simple-mindedly strapped to their propagandistic goals. Strangelove has propagandistic goals I’m more sympathetic too…but overall for me It’s a Wonderful Life has the edge in that Jimmy Stewart’s performance pushes against the entire film in a way that’s way more disturbing/compelling than anything in Strangelove. But obviously mileage differs.

Dr Strangelove’s definitely no Alphaville. But I don’t think a great theatrical performance makes that much difference in this regard; Alan Rickman’s Snape makes the Harry Potters less silly, maybe, but it doesn’t eradicate the problems with Rowling’s conception. Jimmy Stewart makes It’s a Wonderful Life less painful and more nuanced, but he doesn’t actually make it mean something that significantly different.

I don’t think a film being dated, even in a sour way, makes it “irrelevant” exactly, though. Sirk influenced Todd Haynes in interesting ways. Historical objects aren’t irrelevant. I think it’s a question of whether it continues to interact with the culture outside of its moment, whether it can function dialectically or not. The sour ones tend to be less receptive to ahistorical readings – the moment they were made in is vital to understanding them. Godard’s Maoist films definitely fall into that category (ironically, since they try so hard to be dialectical), and they’re pretty abysmally bad. The best films about the Cold War, though, for example, speak to ideological tensions in geopolitics even when their specific geopolitical context is past. But I also think Fail-Safe is a little better at that than Strangelove. Godard’s better films are almost uniformly excellent at it. Robert’ll have to defend Strangelove for you; I didn’t put Kubrick on my list for a reason.

I didn’t mean to say one had to choose. Everyone’s entitled to their preferences. I’m not all that big on Strangelove at this point in time in any case. Kubrick was the first filmmaker I got into as a teenager, but his work seems oppressive to me now. In general, his films are over-controlled, relentless, and not the least bit playful. Even Strangelove seems overdetermined. But I do think it’s much more sophisticated than Fail Safe, which strikes me as the same thing played earnestly straight, and with far weaker results. If memory serves, Kubrick and Peter George, who wrote the novel Strangelove was based on, successfully sued the makers of Fail Safe for infringement.

“In general, his films are over-controlled, relentless, and not the least bit playful.”

Maybe so. My least favorite auteur is Cassavetes. No one’s funnier than Kubrick to me.

And is there another film better than Strangelove at critiquing the mixture of bureaucracy-speak, fascism and individualistic machismo? I’d like to see it if there is.

I think Stewart’s performance does actually change It’s a Wonderful Life in pretty significant ways. His breakdown is soooo much more intense than anything else in the movie; it almost demands you read the film against itself. The saccharine triumph of smalltown life folds up around his despair, and the revelation that it’s all okay is never nearly as convincing as the panic that it isn’t. I’m sure I’m not the first one to suggest that the back half of the film can be read pretty easily as a psychotic episode.

It’s a Wonderful LIfe is an infinitely better film than any of the Harry Potters in the first place…and while I like Alan Rickman, he’s no Jimmy Stewart.

Noah, what do you think of Jimmy Stewart in Hitchcock’s films — given that you’re not a fan of Hitchcock? You may have gone over this before, but I can’t remember if you have.

I’m not a big fan of Hitchcock OR Stewart in general, but I absolutely love Rear Window and like Vertigo pretty much too. I think Stewart’s character is kind of smarmy in both of those.

And Charles,

“And is there another film better than Strangelove at critiquing the mixture of bureaucracy-speak, fascism and individualistic machismo? I’d like to see it if there is.”

This probably isn’t what you’re looking for since it lacks the geopolitical scope and isn’t in English, but my go-to film for effective satire, and in particular satire of machismo is Juzo Itami’s Minbo no Onna aka Anti-extortion Woman. It’s pretty clearly critical of its subject (yakuza extortion tactics and Japanese culture in general), so much so that it resulted in attempts on the director’s life, yet wraps itself as an endearing cute comedy.

It’s been a long time since I saw Strangelove, but as of last viewing I thought it was lesser Kubrick. Something about the bluntly polemic nature of it rubs me the wrong way. It feels like since he’s dealing with an acknowledged “big issue” he’s not quite sure of himself enough to ever stray off-message, which works wonders for polemic clarity but kind of kills the humor and cogency of the critique for me. I suppose you could read even that as an ironic parody of the political discourse, but in a lot of his later films I think Kubrick was willing to embrace a more ambiguous tone and less of an obvious message, even while loathing war and other big issues. I appreciate those later films a lot more.

I love Imamura too, by the way. I saw Profound Desire of the Gods twice in one night back when it was playing at BAM.

Ave…sorry, I didn’t mean to say I dislike all Hitchcock. Some of his films (like 39 Steps) are often lauded but do little for me. The Jimmy Stewart films (and some others, like the Birds) I like a lot though.

“It’s easier for me to list films than directors. My favorite 20 or so, although I’m not making a canonicity argument for any of them:

The Fabulous Baker Boys, Pandora’s Box, City Lights, The Rules of the Game, Brief Encounter, L’avventura, Weekend, The Conformist, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, The Godfather/The Godfather, Part II, Chinatown, Jaws, Nashville, Annie Hall, Tootsie, Ran, Carlito’s Way, Before Sunrise/Before Sunset, Out of Sight, Mulholland Dr.”

I’m late to this, but just wanted to respond. I find it a lot harder to list individual films if only because there are too many that affect me. That said, the one I would question from your thread is Brief Encounter. It has some really nice cinematography but the internal monologues and flashback framing device feel a little too artificial and hokey to me. My appreciation of David Lean begins and ends pretty much with Lawrence of Arabia. Carlito’s Way is an interesting choice for De Palma. My favorites are probably the most obvious ones — Carrie, The Untouchables, Casualties of War — plus maybe Femme Fatale and Phantom of the Paradise…

Top twenty overall would probably go something like this, more or less:

Lawrence of Arabia, Prospero’s Books, Peking Opera Blues, Rashomon, Freaks, Sherlock Jr., The Muppet Movie, Akira, The Lady From Shanghai, Three Crowns of the Sailor, Olympia, The Tenant, Soy Cuba, Zu: Warriors From the Magic Mountain, The Fly, McCabe & Mrs. Miller, Tampopo, High Tide, The Red Shoes, Picnic at Hanging Rock, Sunset Blvd., Too many ways to be no. 1, West of Zanzibar.

…that looks like more than twenty, but it’s difficult to limit it.

Oh yeah, Carrie should be in the top 20 somewhere too. Like I said, too hard to limit myself when sticking to individual films.

“Ave…sorry, I didn’t mean to say I dislike all Hitchcock. Some of his films (like 39 Steps) are often lauded but do little for me. The Jimmy Stewart films (and some others, like the Birds) I like a lot though.”

Thanks for clarifying, Noah.

Noah,

Just realized you said you didn’t like The 39 Steps. Huh, It’s not a masterpiece or anything, but for his non-Rear Window, The Birds, Vertigo Ones I thought it was pretty well-crafted fluffy entertainment. I guess given your distaste for Jaws, it would make sense that “mere” craft wouldn’t do it for you, but I still liked how Hitchcock piled on a bunch of ordinary joe/josephine side-characters who interrupted the chase narrative. Like the farmer and his wife. It felt like Hitchcock was opening up the genre a little bit, sort of like what Ford was trying to do in Stagecoach a couple years later. I think that’s something Hitchcock tried to do in a lot of his later thrillers as well but it seems more clumsy and mechanical to me in North by Northwest and Strangers on a Train, which I think are even more-celebrated. maybe I’m misremembering it though, it’s been a while since I saw The 39 Steps.

I wasn’t super into north by northwest either; not sure I’ve seen strangers on a train.

Here’s my 39 steps review.

Loved Strangers On A Train, and North By Northwest. Throw Momma From the Train, also underrated.

I vote for Terry Gilliam as America’s greatest director, though. Time Bandits, Brazil, and Munchausen, especially, but I was also a big fan of the Fisher King and 12 Monkeys (that was him, wasn’t it?) when they came out. The Grimm thing was pretty awful, and I haven’t seen the Hunter S. Thompson one, but all in all, his work almost always pleases me. The documentary about the collapse of his Don Quixote project is also a great watch.

I’m with RSM on some of this, though. I loved Tootsie and The Godfather, and some of Spielberg’s stuff is ok too. I loved the first 2/3 of AI (it does fall apart at the end, though), and Minority Report was also good. Catch Me If You Can was surprisingly quite good as well, if my memory of it is accurate. All of the Indiana Jones movies, (except the last one) also were enjoyable. Not great art or anything, but he definitely knows how to put together an action movie.

I like Strangers on a Train better than North by Northwest, but I still think it only has two and a half really effective scenes. The stalking at the carnival, the botched attempt to socialize by strangling an old lady at a party, and the half of the climactic scene that focuses on the old man crawling under the out-of-control merry-go-round to turn it off. So it fails Howard Hawks’ test by half a great scene and a bunch of not-bad ones – lol.

Funny thing though, Throw Momma From the Train more than makes up for all of the shortcomings of ‘Strangers’ in my book, even with the blond beauty inexplicably falling for smug douche-bag trope – which I choose to read as more hitch-cock parody. I agree that it’s a great movie. I like to imagine that Billy Crystal died or went to jail at the end and the last couple scenes are just Danny De Vito’s pop-up book.

Momma and Owen and Owen’s Friend Larry. Just the title makes me smile.

Good call on Terry Gilliam! He’s uneven, but I think Time Bandits at least is near perfect.

eric,

Yes, 12 Monkeys was Gilliam. That’s probably my favorite, also love the original, La jetée.

“the Coen Brothers are way more interesting to me than Scorcese or Coppola (though they’ve kind of fallen off a cliff recently….) I like David Lynch too….”:

Lynch can be great. A limiting factor for the Coen Bros. is their flaccid irony. They’re interesting, to be sure, but like many ironists the frequent winking comes off as smugness or just lightweight glibness.

“Anyway, to get vaguely back on topic maybe…any love in here for Spike Lee? And am I crazy for thinking his films are maybe more Godard-like than most anyone we’ve mentioned?”

Spike is pretty good when he’s angry (Malcolm X, Mo’ Better Blues, Do the Right Thing, that New Orleans film). When he’s not, he’s a hack (She Hate Me). I don’t think him and Godard have much in common. Who does?

“Davis and Coltrane were snooty avant-garde poseurs, not people-pleasing genre hacks.”

Have you heard Davis’ Time After Time remake? Or even worse, his Human Nature? Both are pure genre-hackery. I think Davis in general was people-pleasing. “Kind of Blue,” of course. “On the Corner” and “In a Silent Way” are among the coolest records of all time. On the other hand, “Bitches Brew” definetly mandates more advanced knowledge (I can’t get into it), though that somehow was a huge seller. I’m agnostic on Coltrane’s late period; maybe it sounded better live.

“Godard’s Maoist films definitely fall into that category (ironically, since they try so hard to be dialectical), and they’re pretty abysmally bad.”

Though they just might have one or two minor saving graces. I like that bloody outstretched arm at the 45:16 mark from British Sounds/See You at Mao. (NSFW!)

“Kubrick was the first filmmaker I got into as a teenager, but his work seems oppressive to me now. In general, his films are over-controlled, relentless, and not the least bit playful.”

Yup, that’s a frequent general critical consensus. Your comment pretty much sums up “Barry Lydon.” It’s tone-deaf and terrible.

My favorite directors off the top of my head? Chris Marker, Godard, Welles, Altman, Lang, Bunuel, Pudovkin, Jean Vigo, Tarkovsky, Jean Cocteau. And Bertolucci, but only for “1900.”

—————————

Robert Stanley Martin says:

I didn’t mean to say one had to choose. Everyone’s entitled to their preferences. I’m not all that big on Strangelove at this point in time in any case. Kubrick was the first filmmaker I got into as a teenager, but his work seems oppressive to me now. In general, his films are over-controlled, relentless, and not the least bit playful. Even Strangelove seems overdetermined…

—————————–

Yes, there’s a hermetically-sealed quality to Kubrick films. Although he actually made room for improvisation (prior to the actual filming) in his “intensive rehearsal” periods. From which came inspired bits of lunacy like Peter Sellers (as Dr. Strangelove) ad-libbing “Mein Fuehrer, I can walk!” and Malcolm McDowell as Alex the Droog, asked by the director to sing a tune whilst practicing a beating, picking “Singin’ In the Rain.”

(Speaking of “lesser Kubrick,” I was astonished to find, after all the praise it had gotten, how crudely heavy-handed A Clockwork Orange was.)

——————————-

ave says:

…I’m not a big fan of Hitchcock OR Stewart in general, but I absolutely love Rear Window and like Vertigo pretty much too. I think Stewart’s character is kind of smarmy in both of those.

———————————

He becomes obsessively creepy in Vertigo; his sweatily molding Kim Novak into the girl of his dreams echoing Hitchcock’s later trying to make a Grace Kelly out of Tippi Hedren. (“Hitchcock’s plan to mold Hedren’s public image went so far as to carefully control her style of dressing and grooming….” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tippi_Hedren )

Kudos to Stewart for not being afraid to muss his all-American nice guy screen image…

I think the Coen’s can do interesting things with the irony at times. Raising Arizona is pretty sincerely in love with its characters I think, for example. And like a lot of satirists, they have definite moral commitments.

Davis’ fusion period is the stuff of his I really like. Same with Coltrane’s late noisy squanking.

In terms of the Hitchock films, I can watch Cary Grant in pretty much anything… and Jimmy Stewart too. Which is why Philadephia Story is such a great movie—you get both of them (and Katherine Hepburn! Hot damn!). I love the fact that there are other “Throw Momma” fans out there, though. Definitely one of DeVito’s finest moments (let’s not recount the many horrid ones… Twins anyone?)

I also thought I would watch Meryl Streep in pretty much anything. Then I rented “Julia,” her first role I think, but which actually stars Jane Fonda and Vanessa Redgrave. So ended my quest through Meryl Streep’s IMDB page. But I (wildly) digress.

Streep is the greatest actress whose appearance tells me to stay away. I hate just about every film she’s ever been in.

French Lieutenant’s Woman? That’s actually a good film of a better book.

The French Lieutenant’s Woman is very good. Need to see more of Karel Reisz’s movies, especially Morgan!

De Vito has been in a bunch of turkeys, but I generally like him as a director. Nothing tops Throw Momma, though.

Charles mentioned Mario Bava. I think “Black Sunday” was great, arguably one of the best-ever horror films. This was this inspired craftmanship to it. None of his other films come anywhere near it, unfortunately. Where Black Sunday is taut and pointed, his other films succumb are mawkish and soggy in their narrative.

How could I forget Jean Vigo!? Since we’re supposed to be talking about _Éloge de l’amour_ my favorite moment in said film is the dialogue set in the same place were Jean Vigo filmed _L’Atalante_. While it happens we listen to _L’Atalante_’s composite track. A truly Deleuzian moment…

I hadn’t noticed that. But given how dense his films are….. I guess watching it four times is not enough.

“I think I’d agree that Godard is self-important (often), boring (not infrequently), and anti-American”

Well, many if not most artists are self-important, aren’t they? Bono & The Edge were on Letterman a few months ago. Boy, did they come off as full of themselves, but that probably shouldn’t be a surprise.

One more note about “Eloge de l’amour”- the main character at one point states (to paraphrase) “Make over $5000 a year and that’s when you start developing a snooty attitude.” I think that line is quite telling of JLG whether he simply invented it or if it came from his experience.

Not that a lack of funds or attention equals humility. Of course not. But in interviews he has almost always sounded relatively humble, even back in his “golden” period.

“Same with Coltrane’s late noisy squanking.”

So his most controversial and abtuse period is not “snooty posing?”

Of course it’s snooty posing! It just happens to be good snooty posing.

The original contrast was between snooty posing and genre hackery, right? I was trying not to privilege one over the other as a whole….

Steven, you’re killing me: Kill, Baby, Kill? Twitch of a Death Nerve? Lisa and the Devil? You can see traces in all modern body count movies (granted, only Noah and I would probably see that as a value), Lynch and Fellini. Those are probably my favorites, but I do love Black Sunday, too. It’s true that I mainly love Bava just for the look of feel of his films, more than the narrative content (which isn’t the best). I might say the same of Godard, I guess.

I’ll try FLW, Eric, just because you haven’t steered me wrong with your suggestions.

And, while Coltrane isn’t my favorite in avant-garde jazz, I don’t really get “posing” from listening to him. It always sounds like he’s really there, struggling to achieve something.

Now that he’s finally come up, I will take this moment to say that I think our next film roundtable should be Fellini.

I really really like this phrasing Charles uses: “he’s really there, struggling to achieve something.” I think there’s a tendency to view any present struggle as “self-important.” There’s pressure for a kind of nihilistic and deprecatory self-distance, and anything other than that is parsed as self-importance. I think that’s a problem — it homogenizes things, and makes ambition something which always must be qualified — qualified by a cynicism that mistakes itself for realism. What could be more self-important than that?

I reiterate that my original comparison was between self-important poseurs and genre hacks. It’s a binary where everybody sucks (or is equally virtuous, whichever you prefer.)

But…I do like the most pretentious Coltrane a lot more than the less pretentious Coltrane…but that doesn’t mean the most pretentious isn’t pretentious. It’s extremely self-consciously avant-garde; it’s deliberately off-putting; it fetishizes it’s own struggling artistic stance; it makes sweeping spiritual claims (“A Love Supreme”; “Ascension”). You can like it despite its pretension; you can like it because of its pretension; you can like it next to, or over beside its pretension, but to claim that it’s not pretentious is loopy.

I think the confusion that I see in Caro is mistaking the binary as pretension vs. realism? Realism is really pretentious too in a lot of cases (Steinbeck, Shaw…just lots of people with pretensions claim they’re doing realism.) The issue is generally pretension vs. genre…or, like I said, posing vs. hackery. Those are your choices.

Godard conceives of himself as an artist, working in an avant-garde idiom. Coltrane does too. It doesn’t matter whether they’re in the moment, or whether their ambitions are fulfilled or whether they’re great artists (which I’d say Coltrane is…I’m a little iffy on Godard, I guess.) Pretension is a cultural category, and by virtue of how their work figures culturally, and they’re awareness of how their work figures culturally, they both absolutely qualify.

To me, the problem isn’t that high art is dismissed. Nor is the problem that genre work is dismissed. The problem is that people mistake the identification of a work as high art or genre as an identification of quality. And it isn’t. It’s the identification of a cultural position. To make a statement about quality, you’ve got to engage with the individual work more fully than that.

Harold Pinter did the screenplay, Charles…so, it’s got that going for it. On the downside, there’s Jeromy Irons.

Coltrane’s definitely pretentious in the later period stuff, but awesome nevertheless. Likewise with Miles Davis’ fusion.

I kind of agree with Charles… “posing” and being pretentious aren’t the same thing. Being pretentious is just thinking and acting like you’re important. One can do that “honestly,” I think. “Posing” is pretending to be and acting important—self-consciously staging the self in that way. I don’t know enough about Coltrane’s public persona to say he’s posing or not.

Dylan is a poser, as is David Bowie. I like ’em anyway.

I wasn’t trying to set up a binary “pretension versus realism”…I was trying to say I’m not getting the binaries here at all. Eric really hits it, I think — posing is not the same thing as pretentious. There are degrees of posing, but being in some pose is almost inevitable. Even hackery is a pose. And genre can certainly be pretentious. Let’s take Neal Stephenson…or rather, let’s not and say we did.

I think pretension requires something more than artifice or ambition, something gesturing toward delusion and falseness and obscurantism.

So I’m just not seeing these particular binaries in play here at all — I’m seeing an elision of the distinction between consciousness and “pretense” such that it’s hard to make distinctions between expressing intellectual curiousity and showing off, between attempting to be meaningful and attempting to impress somebody. I’m seeing a fictitious notion that there are some things in art that are posed and other things that aren’t. There’s nothing, anywhere, ever, that’s any more posed than the hackery of genre…what could possibly be more posed than formula romance?

I guess I just don’t think that pretension is actually a cultural category in any meaningful sense — it’s a psychological category, sure. Some people are pretentious, passing themselves off as something without doing the work to really be that thing. And I’d be ok using “pretentious” to describe art that’s gesturing at being intellectual for show, rather than to really grapple with intellectual issues. But more often than not the term is a smokescreen people use to collapse cultural categories, not to articulate them — to elide the differences between Godard and Coltrane by saying “that’s pretentious”. It tells you nothing about Godard or Coltrane. It’s not clear to me there’s ever any point in naming something so, unless you’re actually talking about psychology.

I tend to like posers BECAUSE they’re posers. Why is “authenticity” such a fetishized facet of contemporary identity?

Caro, saying that Coltrane and Godard are pretentious is quite informative about both, I think. It’s a way to indicate that they’re both avant garde, that they’re both high art, that they both have (at best) a distant relationship to genre, that they’re both willing, able, and ready to be irritating, boring, and off-putting rather than entertaining. It tells you broadly where they fit in the cultural landscape. Which seems fairly useful, as words go.

Of course everything’s a pose, in some sense. And I’m certainly no more taken with authenticity than you are, I don’t think; I just wrote a piece about Amy Winehouse, and thinking about the role of authenticity in her career is pretty thoroughly depressing, as just one example. Still, poseurs isn’t coloquially used solely to mean people who pose, I don’t think. It’s generally used to describe people who have high-art pretensions; they’re posing as being smarter or more artistically valid than others. And both Coltrane and Godard absolutely do that.

Also…it’s worth recognizing, I think, that just as genre folks are posing, high art folks have major investments in and around authenticity. Coltrane’s authenticity claims are extreme even by the standards of American music. And I think Charles in his piece does a good job of suggesting that Godard’s distancing of authenticity claims in 1 + 1 doesn’t actually make those claims disappear so much as it just makes his use of them more callow.

And, as Terry Eagleton I think pointed out, the pomo aversion to authenticity can have its own downside. It’s hard to be a Marxist without some sort of fairly firm commitment to reality. I think this is actually something of a struggle in Godard’s work, isn’t it?

I think the colloquial usage of poseur and pretentious is extremely problematic — they aren’t actually words I hear genuinely non-intellectual people using to mark “avant-garde” or “high art”. They tend to be slurs that intellectual people — intellectual poseurs? — use against people they don’t particularly like. I don’t think they’re used consistently at all to denote any set of qualities — I think they’re markers of judgement that signal more about a given intellectual’s taste in intellectual entertainment or stimulation than anything about that entertainment itself.

I don’t think anti-realism is much of a problem in Godard’s work — he’s very much in that same Kant/Bergson universe right along with all the post-Marxists from Althusser right up through Laclau and Mouffe. Reality is always a question, but it’s very much not one that has an authentic answer…you even see that in the “personal realism” of Bazin’s take on Bergson, even though the Althusserians gave him hell for it.

I want to respond to Charles but I’m trying to see the movie first…it’s supposed to arrive from Netflix any day! The thread will live on!

It’s hard to be an artist without some sort of fairly firm commitment to reality. That’s what aisthesis is all about…

Well, I was using it in pair with “genre hack”, the colloquial use of which is also a slur. And perhaps a problematic one. (Though Domingos would surely disagree!)

I would say that anti-intellectualism is certainly a problem, but it’s not the only problem. Critiques of intellectuals are often not completely unrelated to class critiques, for example. If genre hacks have to defend themselves for being genre hacks, I don’t see why pretentious artists shouldn’t have to defend themselves for being pretentious artists. Everybody should lose, and none should have prizes.

You’re obviously much more conversant with Godard than I am…but in my very limited exposure, it does seem to me like his radical politics and his commitment to artificiality sometimes trip each other up. That seems to be what Charles thinks is happening to some extent in 1+1…? Or at least, that seems like one way to interpret his problems with that film.

————————

Charles Reece says:

And is there another film better than Strangelove at critiquing the mixture of bureaucracy-speak, fascism and individualistic machismo? I’d like to see it if there is.

————————

There is none!

Not to mention, I wonder how many youngsters (relatively speaking) here even get many of the film’s topically satiric jabs. Such as the right-wing dread of then-new fluoridation; when JFK made the false assertion that the Russians had more nuclear missiles than us, calling it a “missile gap”; with a character in the movie saying, “We must not allow a mineshaft gap!

The satire in Dr. Strangelove (“…one of the first American films to openly flaunt the scientific and military and poltical limitations of language”) and 2001: A Space Odyssey discussed in pages 170-178 at http://tinyurl.com/7rhojyh .

More re “possibly the greatest film satire ever produced,” with none other than the exceedingly-hard-to-please John Simon pronouncing it the best American movie: http://nothingiswrittenfilm.blogspot.com/2011/05/dr-strangelove-or-how-i-learned-to-stop.html .

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…If genre hacks have to defend themselves for being genre hacks, I don’t see why pretentious artists shouldn’t have to defend themselves for being pretentious artists.

————————-

Certainly so! The problem being, though, that any attempt at seriousness, dealing with a weighty subject, or injecting depth into genre work can be smeared as “pretentious.”

I’d think that the term should be reserved for work which bombastically flaunts its high-Art aims…

http://www.artcritical.com/blurbs/JSMcMillian.htm

…yet is empty at its core. As mentioned on another thread, when an artist aims high, and hasn’t the wherewithal — life-experience, maturity, intelligence, wisdom, creative depths, ability to critically see their work from an emotional remove, etc. — to carry things through properly, what we get is melodrama rather than drama (see Kubert’s “Fax from Saravejo,” most of Eisner’s “serious” work), heat rather than light, an empty imitation of the form of high-minded art (sorry, BWS: http://www.boomspeed.com/hungabout/FATE_SOWING_STARS.jpg ) without its depths or substance.

Authenticity is definitely worth critiquing, but I don’t think we can get rid of it. Godard certainly thinks his cinema is more authentic towards the real than Hollywood’s is. I don’t think you could criticize something as being poseur if you don’t have some notion of the authentic. Some art, say Doo Wop, is authentically pop, it doesn’t pretend to be something else. Same with the Ramones. And you might say KISS is authentically commercial. They admit to being about money. I’m not getting what Coltrane is supposedly pretending to be. He followed his muse. I don’t think he was setting himself up as superior art to Miles Davis (whereas Davis clearly thought his friend went off the rails into pretentious shit). If Ascension really works on you, I don’t see the title as pretentious. Sometimes individuals are correct in thinking they’re brilliant, you know? Maybe Cecil Taylor believes his music is superior to most mainstream jazz, but isn’t it? Wynton Marsalis believes himself to be authentically carrying on the tradition, not Taylor. Who’s being more authentic to the tradition, the one trying to move it forward, or the one happy to embalm it?

Well, Coltrane acolytes sometimes come close to claiming he’s the messiah…and I don’t know that Coltrane’s work exactly rejects that interpretation. He’s a humble, wounded seeker. Which isn’t not a pose.

But Ascension is still great. And Wynton Marsalis is irritating.

Part of the issue is that jazz was always kind of avant garde even when it was pop; its authenticity claims were always about being the avant garde to no small extent in a way that the blues, for example, was not. The Louis Armstrong quote “if you don’t understand, you’ll never know” — Coltrane’s Ascension is nicely in line with that.

Wow, Noah, you must be the only other person I know, besides me, who likes (or can stand) “Ascension.” Now let’s talk about “Om”…

Try Brotzmann’s Machine Gun, if you haven’t, Andrei. It’s really amazing.