The critical reception of Craig Thompson’s major new book Habibi has been somewhat dismaying. Sometimes, and — I am happy to say — more than occasionally these days, one reads comics criticism of such quality that one is perhaps fooled into believing that the form is finally receiving its due, that we have moved beyond the facile ideological critiques and “story vs. drawing” discussions of yesteryear. But then something like this book comes out and reality bites.

To start with the former issue, parts of the comics intelligentsia seem to be developing an unhealthy obsession with ideological readings of comics. To the extent where a given work is weighed entirely according to an ethical consensus and found wanting because of “problematic” content, most frequently of racist, sexist, or politically offensive nature. Anything else that the work might have to offer tends to be ignored and the notion that something might be good, even great, despite – or even because – of its problems seems inadmissible.

This site has become affected by such thinking in the last year or so to the extent that opening a random article will more likely than not bring the goods. Examples include the endless arguments over Robert Crumb’s racism (in which ‘satire’ has been held up as an inefficacious fig leaf by his defenders), the overblown accusations of sexism directed against Eddie Campbell in our roundtable on his work, the rather one-sided focus on Chester Brown’s choice to depersonalize the prostitutes he depicts in Paying for It, or most recently the discussion of Craig Thompson’s Orientalism in Habibi, which perhaps found its most vicious form in Suat’s review of the book.

I am not necessarily denying that the works in question, or indeed comics history more broadly, are haunted by such issues, nor am I arguing against choosing them as an avenue of criticism — Nadim Damluji’s examination of Habibi is a good example of a considerate approach, while Noah’s obliteration of certain recent DC books offers righteous polemic. The problem, rather, is that such criticism is often informed by a kind of ideological Puritanism that has gained traction in our current culture of taking offense — a Puritanism often blind to aesthetic quality, resistant to uncomfortable discourse, and prone to censorious action.

In the case of Habibi, it seems to me facile and unproductive to harp for too long on its sexism and Orientalism. Yes, it offers both and it suffers from it, but why does that have to be the full story? It is simultaneously, and obviously, a book so generous in intent and so voracious of ambition, that such criticism risks coming off as petty and, more importantly, ends up lacking in resonance.

Does Habibi successfully realize its sprawling ambition? No, it is a bit of mess, frankly, almost claustrophobic in its efforts to cram meaning into a formal structure unprepared for it. There is a distinct unease in the work between its conceptual and formal concerns, an attempt to stretch intellectually within a cartoon framework driven by stereotype and concerned with stylistic élan.

Does Habibi successfully realize its sprawling ambition? No, it is a bit of mess, frankly, almost claustrophobic in its efforts to cram meaning into a formal structure unprepared for it. There is a distinct unease in the work between its conceptual and formal concerns, an attempt to stretch intellectually within a cartoon framework driven by stereotype and concerned with stylistic élan.

As was the case with Thompson’s paragon Will Eisner when he switched to graphic novel mode in the late seventies, Habibi is marked by an insistence on the value of the archetypes of traditional cartooning as a vehicle for the communication of sophisticated ideas. But where Eisner was suggesting untapped potential, Thompson’s cartooning is retrospective, barely transcending pastiche; where Eisner was concerned with paring down his visual storytelling to eliminate the kind of stylistic excess he had practiced in his classic Spirit strips, Thompson has his cake and wants to eat it too, letting his line run away with the narrative; most importantly however, Eisner’s mature cartooning, for all its faults, is animated by a genuine, mostly unpretentious effort to communicate truthfully, whereas with Thompson, whatever earnestness motivated him, the work smothered in conceptual intent.

Which brings me to the other issue I have with the critical reception of Habibi, and comics in general: the lack of sensitivity to how the visuals are integrally determinant of the work. Critics tend not to look beyond the surface qualities of the drawing in comics, and then proceed to discuss whatever conceptual issues are at stake without devoting much attention to how those issues are manifested visually. Even a cursory examination of the reviews published so far of Habibi should demonstrate this. Only a few have been entirely positive and several have been strongly negative in the conceptual assessment of the book and its ‘writing,’ but the majority of the reviewers have nevertheless taken time to commend the ‘art.’

Despite his strong misgivings, Damluji praises Thompson’s “stunning artwork,” and Fatemeh Fakhraie — while stating that she has no choice but to hate the book — “admits” that it is “beautifully drawn,” but does not engage that part of her experience much further. In their ambivalent takes at the Comics Journal Chris Mautner and Rob Clough both call the cartooning “visually stunning,” while the latter adds “amazingly beautiful” and praises Thompson’s “astonishing” attention to detail; Charles Hatfield, for his part, describes his drawing as “gorgeous” in his equally equivocal assessment in the same place.

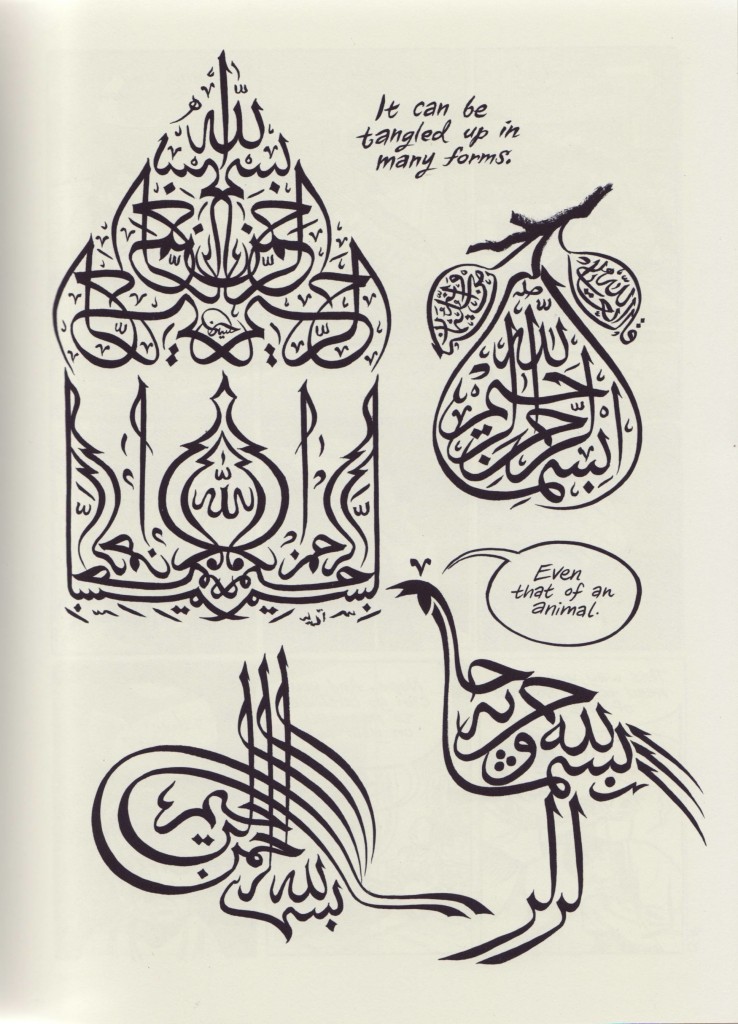

In his notes on the book, Sean T. Collins isolates the “art” in one of fifteen bullet points, calling it “lush and lovely on a surface level,” and describing how Thompson’s line “swoops and curves in a fashion he’s explicitly compared to handwriting.” In her critical examination, Tansim Qutait also picks up on this, describing the book as a “…beautifully crafted volume, the ornately decorated pages broadening possibilities for expression in the graphic novel form, as the calligraphy adds an innovative third dimension to the duality of image/text,” without further detailing why or how that would be the case (calligraphy and comics have a long common history). And Michel Faber of The Guardian grandstands against a paper tiger that would have serious comics aesthetes scoff at technical chops, calling the book “an orgy of art for its own sake.”

You cannot argue with taste, but the uniformity of the reaction strikes me as notable. Belying Faber’s theory, comics have generally been and continue to be valued for the technical accomplishment of the art. Thompson is certainly technically accomplished, but these critics seem to overlook that his virtuosity “…is a conventional sort of virtuosity,” here used “in the service of a conventional exoticism,” as Robyn Creswell puts it in his New York Times review of the book. Or as Suat describes it more bluntly, it “…lacks the emotive and stylistic range to capture the pain and suffering he is depicting (almost everything takes on the sensibility of an exercise in virtuosity or an educational diagram).”

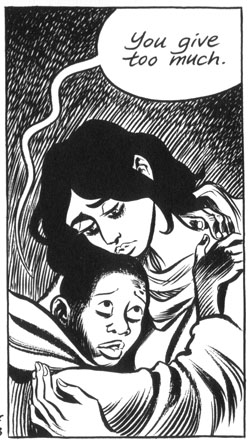

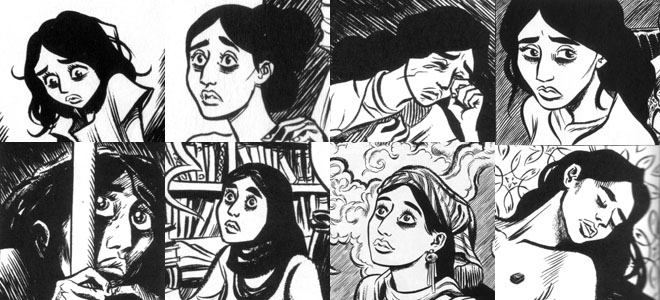

Rarely, if ever, does Thompson’s visualizations of his characters support the book’s implicit assertion that it is more than broad melodrama (which it nevertheless is, or could have been, but more on that presently). Wide-eyed Dodola alternates between wonder, despondency, anger, and bliss through the book, as if following Suat’s educational diagram.

The implied complexity of her emotion as she finally proposes a sexual union with her former charge Zam, after many years of separation, is for example undermined entirely by a banal progression from surprise to pity and doubt that simultaneously overstates and flattens the plea for redemption we are supposed to feel. Doughboy Zam’s evasive maneuvers and flitting baby eyes — supposedly a reckoning after years of denying his sexuality to the extent of self-castration — is not any more persuasive.

Secondary characters fare even worse: as several critics have noted, there is nothing to distinguish the sultan beyond central casting, which makes him hard to care about even as a villain. (This is emphatically not the case with the better of Thompson’s nineteenth-century models in Orientalism: compare for instance Delacroix’ chilling portrayal of the tyrant Sardanapalus). And the characterization of walk-on characters, such as the slaves encountered in the market by the fisherman Noah, is often embarrassingly rote, as if Thompson were not even trying.

As previously noted, I suppose he is following Eisner here, but his proposition that these stereotypes — the stuff of kitsch illustration — can carry his ambitious attempt at reconciling typology and psychological realism is unconvincing.

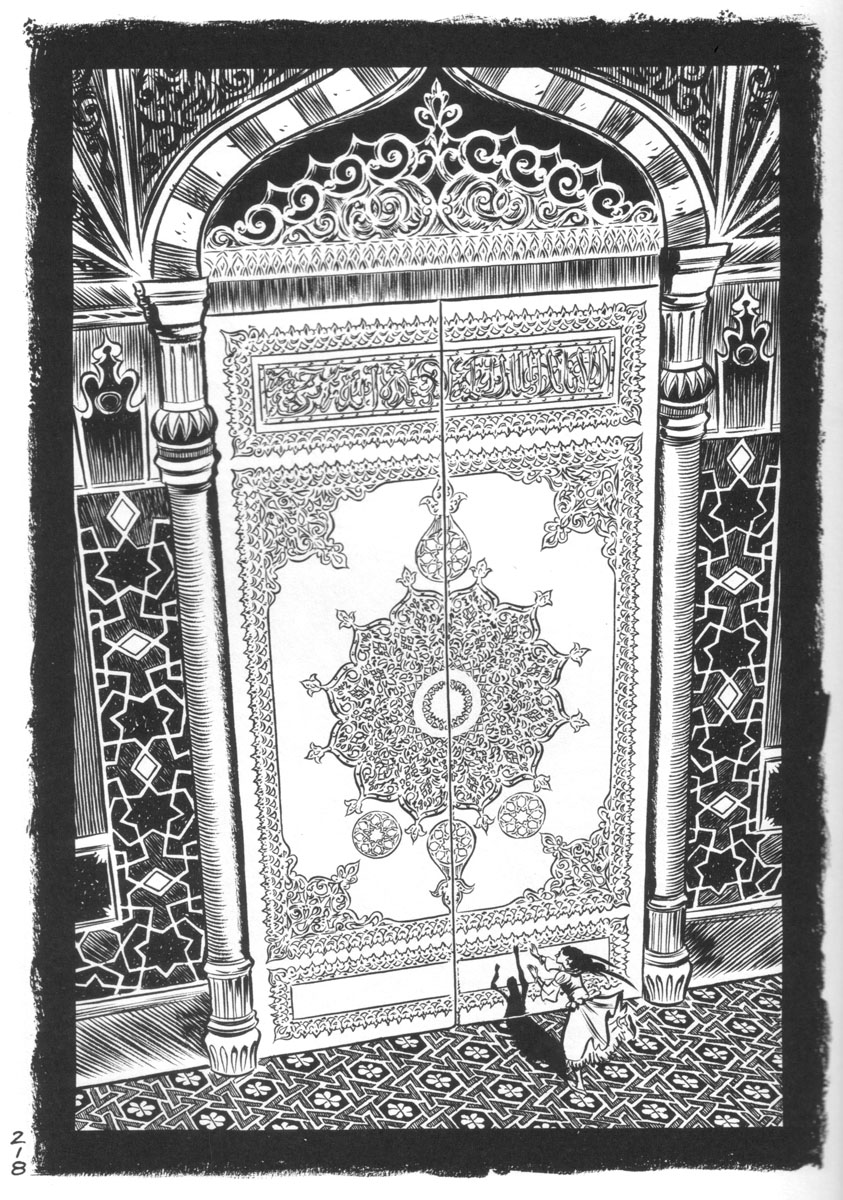

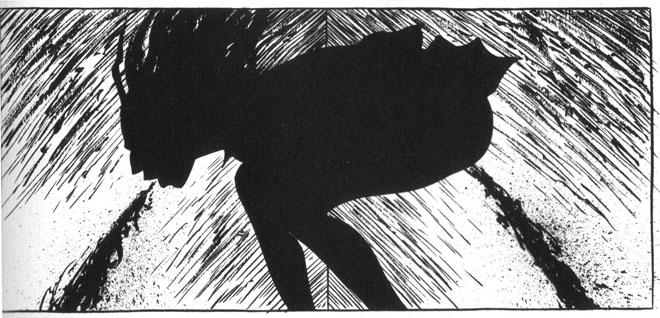

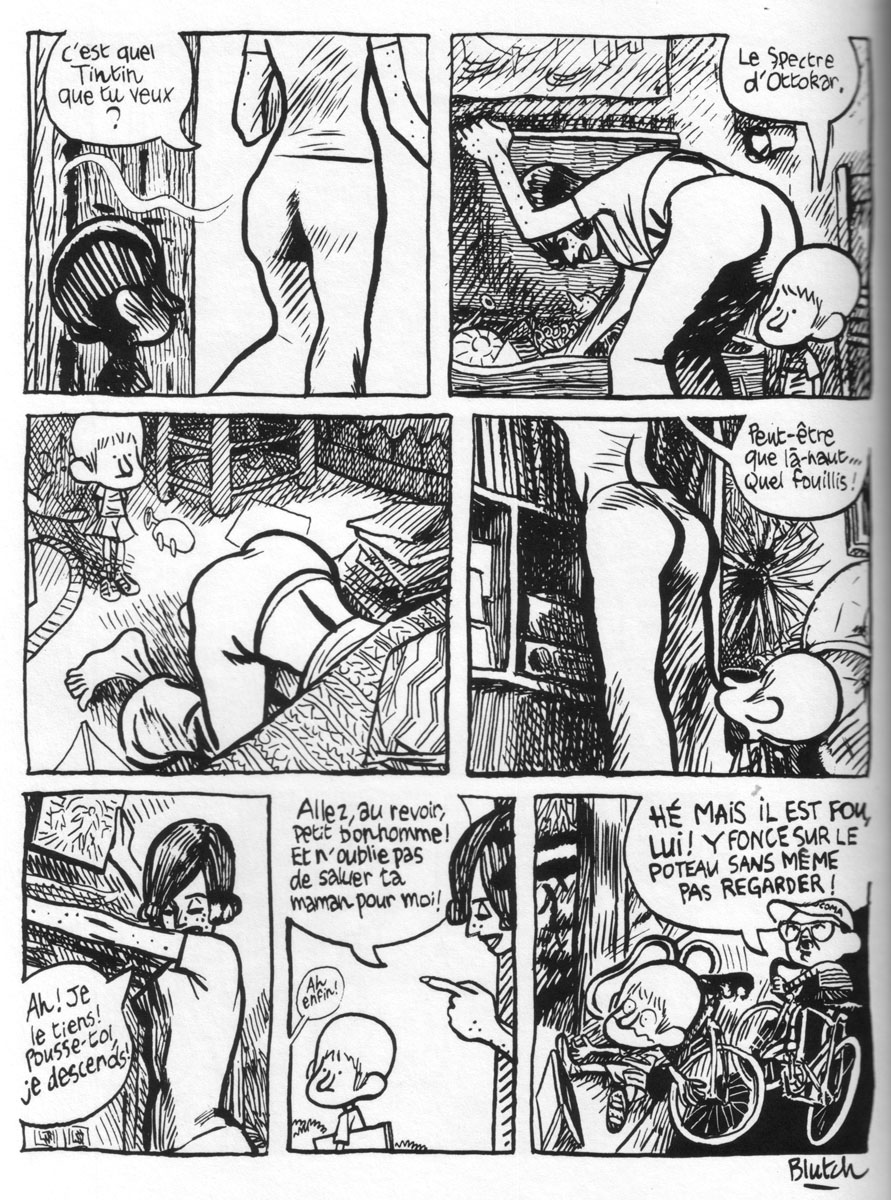

The same goes for his much praised ‘calligraphic’ line. His explication of the word ‘Bismillah’ in the Qu’uran for example is deftly wrought, but his examples sit uncomfortably on the page, one diagram after the next, rather than being woven together harmoniously the way one encounters in good calligraphy. And the line is rather mechanical, incapable of surprising us – every stroke is in its place, and we know where it is headed. Compare Thompson’s other great paragon, Blutch, who for all his faults invariably retains a spontaneity of rendering, a reflexive laxity of control that enables surprise error and insight.

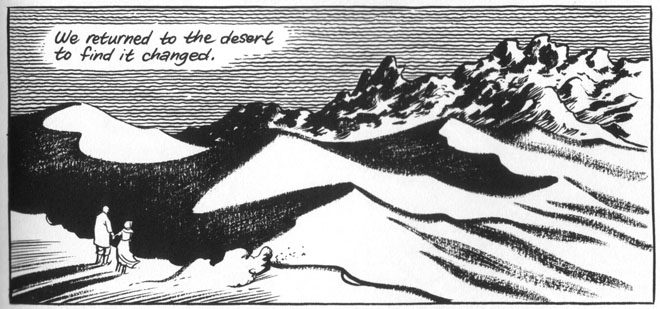

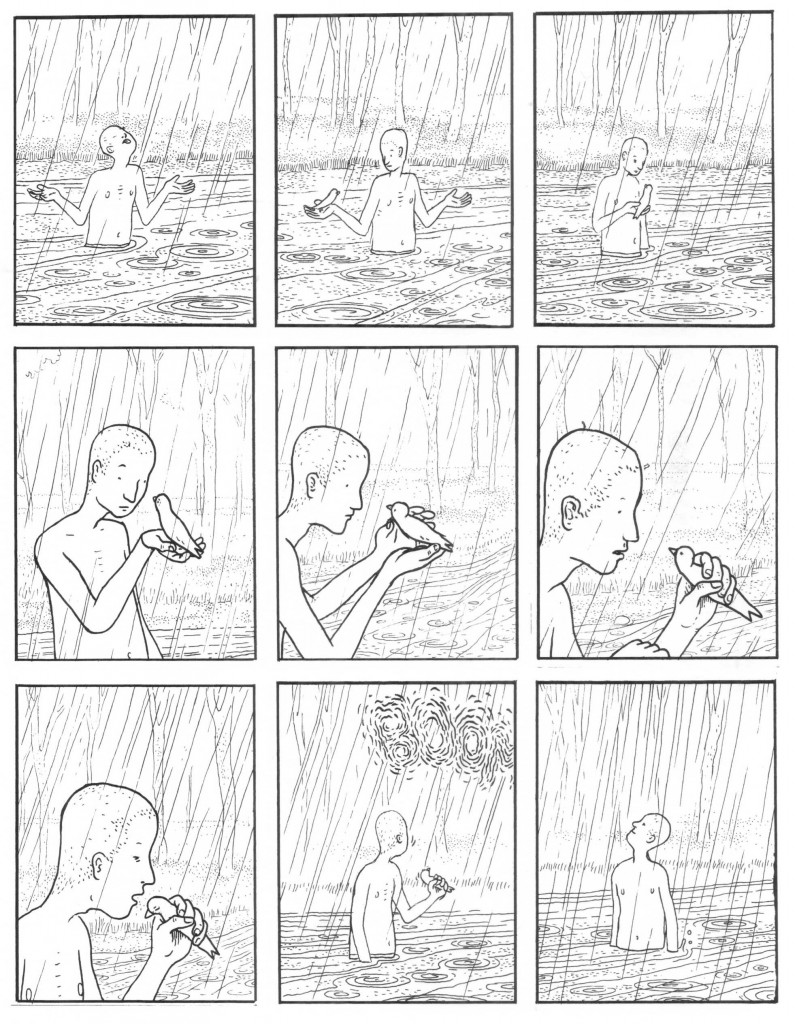

If this comparison with one of the masters seems unfair, one need look no further than a considerably less facile cartoonist than Thompson, who also just published a big book of comics (Big Questions): Anders Nilsen. Though less secure, often laborious, and marked by errors, his line moves with a nervous jumpiness that makes us wonder what meaning it holds, where it is going.

Thompson’s range, similarly, is limited. He uses the same lines to delineate the curve of a sand dune and bodily effluvium.

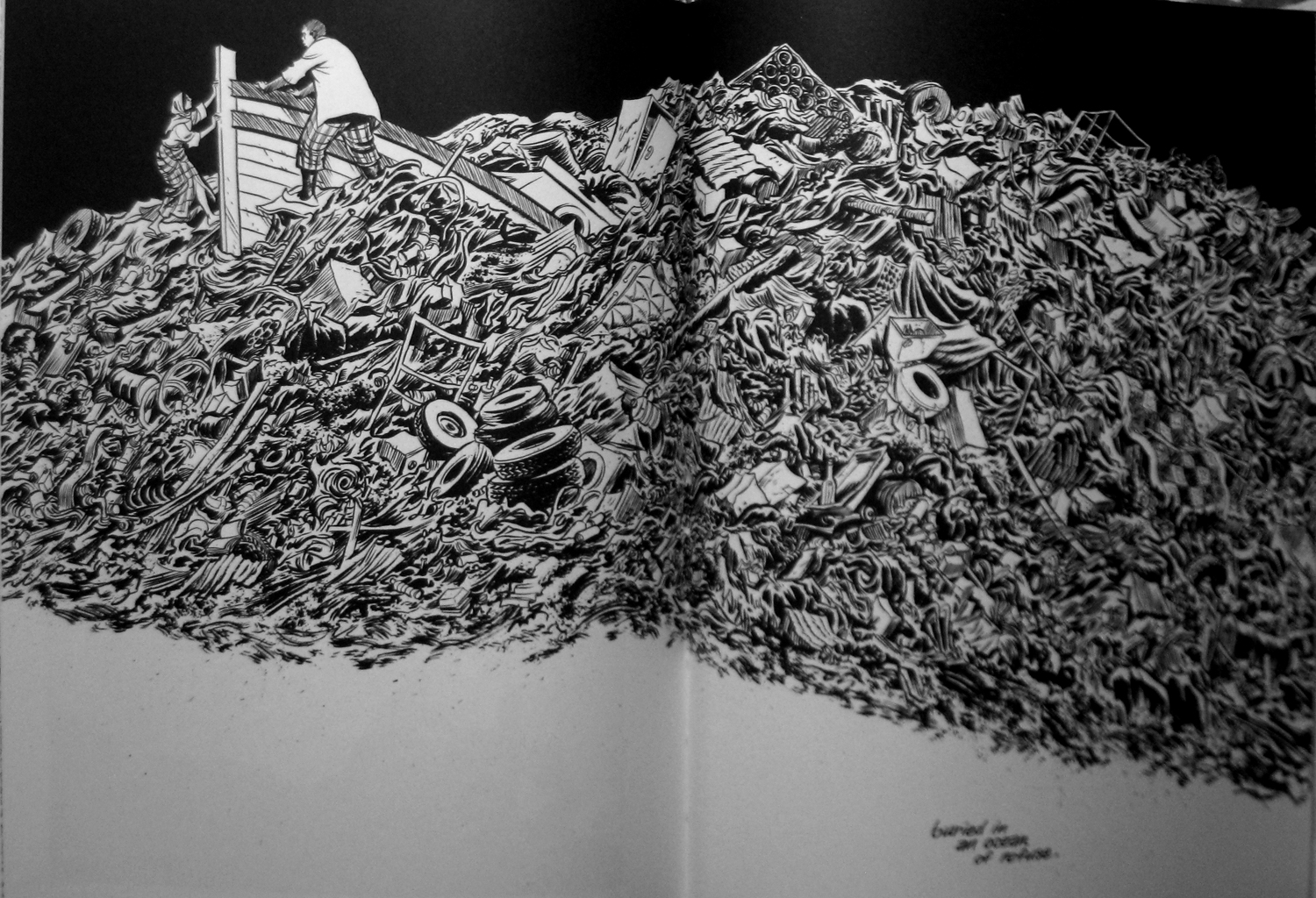

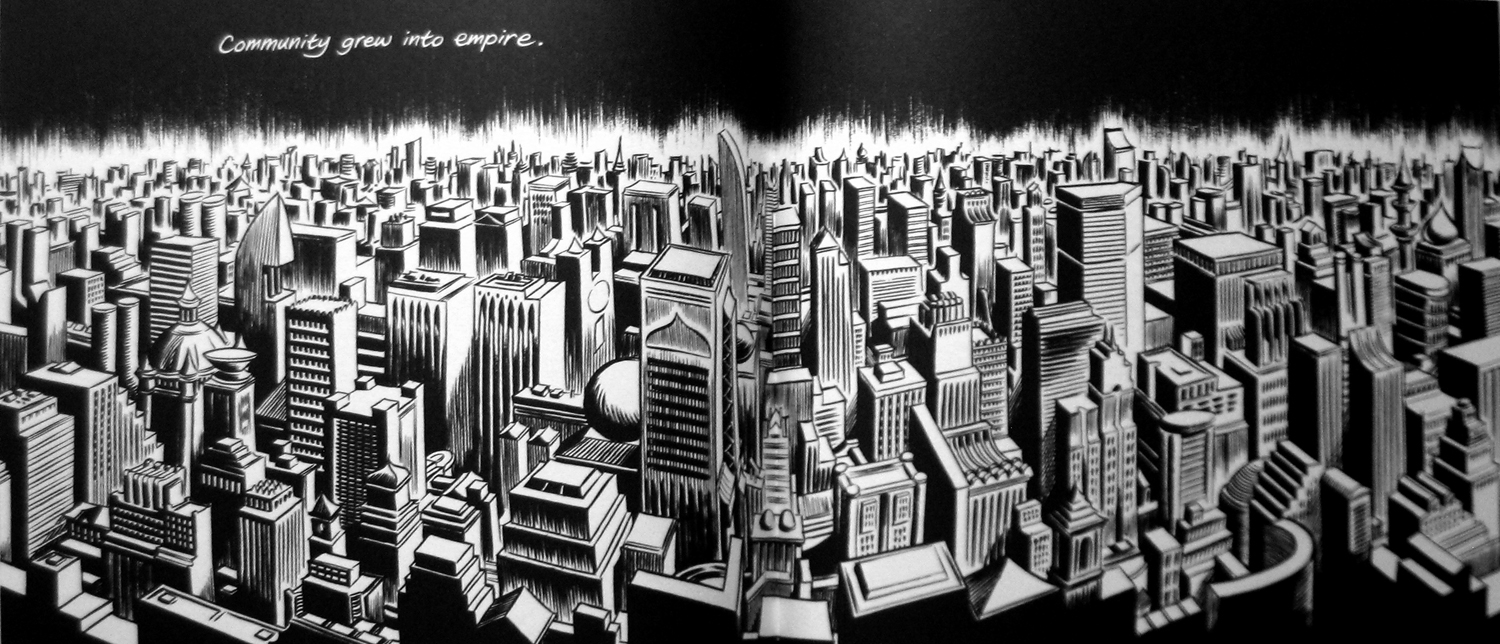

Everything is the same graceful brushstroke, as if that were the main point. The effect is strangely antiseptic in a work that concerns itself so intently with filth and pollution — its mountains of garbage seem designed to wow us more than anything else.

Also, Thompson’s depiction of the great modern metropolis of Wanatolia is bereft of the grimy presence he describes elsewhere, a lifeless construction, all unpacked from the same box: one might argue that this carries a conceptual point about the barrenness of Empire, but it still fails to evoke the environment our heroes will be moving through for the rest of the chapter. Blandness also requires suggestiveness to be recognized as such.

At the risk of repeating myself, my overarching point about comics criticism here is that if one wishes to criticize Habibi’s writing and subject matter, it seems a missed opportunity not to recognize that the problems identified inhere as much in the visuals as in anything else. Merely to describe the art as ‘beautiful’ and otherwise ignore its importance to the work is ultimately doing Thompson — and more fundamentally the comics form itself — a disservice.

Thompson’s deadening control of line and resort to stereotype are part and parcel of the deliberation he brings to his writing and conceptual presentation: everything is there for a reason and he makes sure we know it, even if we sometimes wonder whether that reason is particularly well digested. And in a way you cannot but admire Thompson for his ambition and efforts — Habibi is a smorgasbord of ideas, generously laid out for the reader by a highly talented cartoonist whose enthusiasm is certainly infectious but also, and ultimately, smothering.

Where the work really shines for me is in the passages marked less by overt intent and more by instinct, which was also the case in his previous, autobiographical book, Blankets, in which the uneasy and tentative, if also undeveloped, treatment of the author’s relationship with his brother was by far the most compelling aspect of the story. In Habibi, this unease is primarily located in the treatment of sexual anxiety and transgression, which borders on the obsessive and even the sadistic. It is almost as if Thompson enjoys torturing his characters, especially through sexual humiliation, in a way that suggests meaning beyond the narrative itself.

In Blankets the same themes were treated much more timidly; here, there is a fascinating excess on display. This ties in to the very masculine display of Thompson’s brushwork — executed in what he has described as the “virile” tradition of Blutch and other European cartoonists, from Edmond Baudoin to Christophe Blain (more on that here) — and for which he has employed the tired metaphor of the mark as divine seed more than once, including at the beginning of Habibi. Importantly, it also energizes nervously Thompson’s patently male gaze. A more mature exploration of this tension — a tension fully worthy of his talent and aspiration — would seem to me a fruitful direction for his future work.

__________________

Editor’s Note: This is part of an occasional roundtable on Orientalism and Habibi.

Update by Noah: I try to respond to some of Matthias’ points here.

For a minute there I thought we were finally going to have a positive review of this book on the site…but alas, no such luck.

I still haven’t read Habibi (and probably never will, given no one seems able to make a case for it), but in reference to your discussion of criticism, I guess I’d make a couple of points. First, it’s really not clear to me that ideological critique is a problem of long-standing for comics criticism, or even that it’s especially one now. On the contrary, I think that raising these issues — which are fairly uncontroversially seen as important in other art forms — still causes a lot of push back in comics, whether it’s Eddie Campbell circling the wagons to protect the artist from jackals, or you arguing for less ideology, more formal consideration. I think you’re right that the reason that this site occasionally provokes consternation is because it often focuses on ideological issues…but that’s a sign that others tend to do that less, not that there’s some sort of sweeping consensus of ideological focus.

I certainly agree that talking about line or iconography is useful…but Suat did that, it seems like? In addition, for this book, it seems like a large part of the form is the Orientalism. Thompson explicitly says that he is working in that visual/ideological tradition. Critiquing that tradition isn’t a failure to be attentive to his visual style; it’s being attentive to his visual style. Both Nadim and Kailyn Kent looked at particular visual precursors, for example, and used those in their reviews. Admittedly, that’s not an examination of line, but is an examination of line the only legitimate way to approach a visual analysis?

Finally — I’d just note that it’s interesting that you raise the specter of aesthetic Puritanism, and yet I’d say that your review is significantly more bloodless than many of those your criticize, at least in your criticism of the book. Nadim, Kailyn, and Suat had really impassioned reactions to Habibi; most of the emotion in your review is directed into frustration at other critics. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with that (I like this piece a lot). But I do think the call for balance and justice and cool formal analysis can be its own kind of Puritanism (if Puritanism is to be the charge,) and its own way of not confronting the material (or some aspects of the material) in front of you.

I must say that you surprised me, Matthias: when you started “parts of the comics intelligentsia seem to be developing an unhealthy obsession with ideological readings of comics” (accepting that it is an obsession, why is it unhealthy, exactly? Was the old obsession with craft proficiency – to produce childish schlock, but who cares, right?, we’re not snobs and elitists – healthier?)… Anyway, when you started in the above quoted manner I thought that you would say “yeah, the work has its problems, but…” Instead you proved that comics critics don’t know what they say when they criticize the content while praising the form. I must say: bravo!

Plus: I didn’t know that we completely agree re. “realism”:

“The difference between him [Edmond Baudoin] and his progeny, however, is that his best work seems to be fuelled by genuine ambition to convey something about the world – the nature of impressions, a sense of place, the tug of desire – while they have mostly adapted his very French joie de vivre, the almost demonstrative love of life, woman and the bittersweet vagaries of fate circumscribed by what has become national cliché. They are the Techinés, the Jeunets, or the Gondrys to his Rohmer or Antonioni (ahem, he’s not French, I know).” Yep! What you call my defence of realism is just a requirement by yours truly to find in the work being criticized an: “ambition to convey something about the world.” No art or writing styles attached…

—————————-

Matthias Wivel says:

…parts of the comics intelligentsia seem to be developing an unhealthy obsession with ideological readings of comics.

—————————–

Certainly, but a minor part. Moreover — though I’m one who’s regularly argued against such extremes as damning Hergé or Ebony White as “viciously racist” — it’s a valid reaction to work which traffics in stereotype, even if, as you pointed out, it all-too-often leads to “tossing the baby out with the bathwater”; ignoring cultural context, old-time cartooning tropes, and other mitigating factors. (Such as the fact that, blubber lips and all, Ebony White was a resourceful, admirable and courageous character.)

What’s particularly damning about your essay are the examples of the inadequacy and minimal art-literacy used by other critics to praise the “beautiful,” “stunning” rendering in Habibi.

Your own assessment of its actual inadequacies remarkably astute and perceptive.

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

I think you’re right that the reason that this site occasionally provokes consternation is because it often focuses on ideological issues…but that’s a sign that others tend to do that less, not that there’s some sort of sweeping consensus of ideological focus.

—————————–

Indeed so…

——————————

Finally — I’d just note that it’s interesting that you raise the specter of aesthetic Puritanism, and yet I’d say that your review is significantly more bloodless than many of those your criticize, at least in your criticism of the book.

——————————

Puritans — whether the originals or those, say, crusading against Demon Rum or Innocents-Seducing comics — are actually pretty damn passionate!

I think there are reasons beyond laziness or whatever for critics interested in ideological criticism and, more importantly, the insights from ideological criticism (whether political modernism OR cultural studies) in other disciplines. There are a lot fewer theoretical texts that grapple with the visual than there are texts that grapple with the verbal, conceptual, or sociocultural. Visual analysis often veers into questions of aesthetics or skill or sensitivity without exploring what those aesthetics mean ideologically or culturally. So to some extent you’re asking critics to make a choice between ideological or cultural analyses and aesthetic ones, which doesn’t make sense to critics who believe that aesthetics are themselves ideological and cultural.

For example, why, in general, does “nervous jumpiness” make you “wonder what meaning it holds” more than something more controlled? Why would control itself make something less meaningful? You seem to be saying that the form signals something very specific — but is it really the case that controlled work is always less meaningful than looser work?

Or, when you say “He uses the same lines to delineate the curve of a sand dune and bodily effluvium,” why exactly is this a problem? We use the same words to write newspaper articles and poetry…I’m not saying it isn’t a problem, but it’s not self-evident that this is anything other than an aesthetic observation.

Likewise you reach toward a critique the use of traditional cartooning and illustration for expressive art — but it’s remains mostly a gesture toward the idea that they’re limiting. What are those limits, and why are they limits?

I don’t mean that as a critique of this essay, which is a really good essay on Habibi that points out really important things. I think the issue is that people in comics — and to a lesser extent people in art period — don’t ask these types of questions, and don’t create writing that tries to answer them in general. There is a lot of criticism — but there is much less theory. Because theory is always generalized, not encased in a reading of a text or a work. And the lack of theory diminishes ideological critiques, makes it difficult for them to grapple with the visual issues you raise.

That’s exacerbated by something that I think is at stake in Noah’s comment — the intimacy of the comics community, plus the notion that drawing is handwriting, plus the fascination within US comics with personal narrative, all create this sense that comics are a vastly more personal form than other art, and that makes people hypersensitive to non-formal critical discourse. I disagree with Noah that your essay is more “puritanical;” I think this is a much more scathing critique and may be taken much more personally by Thompson and his defenders than even Suat’s, but that’s because it does pose, implicitly and explicitly, such a challenge to theoretical things that are so often taken as givens here — reverence for technical proficiency and the idea that traditional cartooning and illustration idioms are fully capable, in their current form, of carrying the work of expressive art.

“Puritans — whether the originals or those, say, crusading against Demon Rum or Innocents-Seducing comics — are actually pretty damn passionate!”

True enough. And in that regard I think I was probably wrong to suggest that there’s a Puritanism of formalism. It’s probably better to say that there’s a lot of passion in Puritanism, and similarly a lot of passion in thinking about art in ideological ways. Connecting art to ideology is connecting art to life and morality and things that people care about, and that art cares about too. Talking about line control is interesting also, and I’m all for that sort of thing, but if you talk about line control without ideological content, you end up with a very specialist interest that doesn’t connect to much.

Puritans take art more seriously, and more passionately, than formalists, is I guess the point.

Caro, I think the problem of theorizing visual art formalism is something of a red herring, maybe? It seems like there’s similar problems in reading poems when you get down to the level of formal analysis; Terry Eagleton has several acid comments about hearing the sigh of the breeze in alliteration. There’s always a leap from technical methods and accomplishments to the interpretation thereof, and that’s always going to be subjective and inventive, I think. It’s part of why criticism is more art than science.

I disagree with you that the questioning of technical proficiency in the way Matthias does it is really a strong attack on current reverences. Art in general, and comics in particular, has a long tradition of valuing imperfection over slickness. And I don’t see Matthias challenging the idea that cartooning and illustration are incapable of carrying the work of expressive art. He’s saying that *Thompson’s* work seems to fail here at times…but then he has other examples which he shows as successes. That’s just a critical hierarchy, not an assault on comics as comics, as far as I can see. (Which is fine with me! I don’t see comics as innately less worthwhile than other aesthetic forms.)

There are some related problems — but ideological analysis has a lot more solid ground to stand on with verbal things than it does with visual ones.

Here’s the paragraph I think gestures at (although I wouldn’t call it strong) a more comprehensive critique:

The question is “the value of the archetypes of traditional cartooning for the communication of sophisticated ideas.” But the assertion that follows is that Eisner did something more than “traditional cartooning”, reaching toward an “untapped potential”, whereas Thompson is only doing a “pastiche”. But that “something more” isn’t traditional cartooning — it’s some other aspect of the work that transcends the surface aesthetics. It doesn’t just have the look of cartooning, it doesn’t just make reference to cartooning — it’s something more.

The criticism in that paragraph is of the notion that just having the “look of cartooning” is sufficient to carry sophisticated ideas. You need the something more. But the question about what that something more is, or the relationship of that something more to “traditional cartooning” (other than the way it looks) is still out there, only cursorily explored.

That’s why I think there’s a strong tension here between aesthetics and something more than aesthetics, something still visual but not primarily aesthetic, that isn’t terribly well theorized. And while I think, of course, that you can DO criticism without that theory, such criticism is, generally speaking, going to seem strongly subjective. While this isn’t so much of a problem for aesthetic criticism, it’s a huge problem for ideological criticism. I think that’s why ideological criticism tends to avoid the visual in the way Matthias wants it addressed — it’s much harder to situate it in some more objective context. You end up with statements like the ones I query above, and how you get from those observations to ideology is just not clear. If everything’s ideological, then what’s the ideological implication of those choices about linework?

It’s not really theorizing visual art formalism, though, that’s missing — it’s a visual semiotics as mature as linguistic semiotics. Formalism v. semiotics has these same problems in linguistics too — but there have been thousands of gallons of ink spilled about how to address it. There just hasn’t been nearly as big a range of grappling with that in visual art. That’s why I think saying it’s about not being attentive to the visual is pushing a choice between aesthetic and ideological criticism that’s really problematic.

Right, lots of interesting comments here. Thanks! I’ll start from the top.

When I refer to the “facile ideological discussions… of yesteryear”, Noah, I’m referring to the tradition that goes back at least to Wertham, and would later include Marxists critics like Dorfman and Mattelart, that almost exclusviely studied comics as sociological products, and tended to view comics as a nail for their ideological hammers, without considering the many ways in which they contradicted their analyses.

That being said, and this touches upon Mike’s comment too, I don’t think the best of those critics (and that includes parts of Wertham) were totally off. Comics are interesting as sociological objects and clearly have a history of trafficking in stereotypes and propaganda of the kind so well-suited to ideological criticism.

I tried to acknowledge this in my text, which is by no means a disavowal of such approaches, but rather a caution against the kind of criticism I see a lot of on this site, which tends only to be interested in such issues and as a result is blind to other qualities, some of which might even contradict its arguments, in the work.

These don’t necessarily have to be formal, and I don’t consider myself a formalist — I agree that the impulse in traditional formalism against any kind of conceptual or ideological interpretation is limiting. What I was trying to achieve in the second, longer part of my essay was not meant to be an exhaustive analysis of Habibi (if it were, I would of course have engaged conceptual issues further). It was rather an attempt to show how comics critics often ignore or shy away from including formal and aesthetic analysis in their ideological or conceptual critiques. As I wrote, I think Habibi’s form is part and parcel of whatever conceptual or ideological issues one might detect in it, including of course its Orientalism.

True, Suat touched upon this briefly, but didn’t spend a lot of time on it, and Nadim’s critique had a strange disconnect between acknowledging the book’s ideological roots in 19th-century Orientalist art and at the same time rather uncritically summing his assessment of the form up by saying “From any perspective this is stunning artwork.” I am not trying to denigrate these two essays, which I think are among the best I’ve read on Habibi (even if Suat bordered on the perfidious in passages), but rather that there was a missed opportunity there.

Which is why I’m in agreement with Caro when she says that “aesthetics are themselves ideological and cultural.” That was my point.

That being said, your wish, Caro, that aesthetic criticism be couched further in theory I find problematic, at least if it means the exclusion of criticism that is primarily aesthetic. None of the statements I make on Thompson’s art are meant to be universal — they pertain specifically to Thompson’s art, as Noah says. I’m trying to get at a subjective sensation or experience that I have looking at his line, which may hopefully resonate with others. Theory is a tool generally formulated linguistically and, for all its uses, one I think is unsuited to describing these sensations — sensations in which I find as much truth as I might do in the more general, intellectual frameworks proposed by theory. This ties in, by the way, with the discussion we had about Fragonard, Moebius, etc. a while back.

A lesser point: the comparison of Thompson’s rendering of bodily effluvia and the contours of sand dunes is made to suggest his limited stylistic range in a work that calls for wider representation.

Lastly, the problem of traditional cartoon typology and its suitability for rendering complex reality: it’s an interesting question, but I should think it implicit in my writing that I *do think it’s possible, just as Domingos says in his comment (and yeah, we do agree more often than it might seem!).

That being said, I don’t think *every comic neccessarily has to hit that “realist” register — there’s room for many things beyond that in art.

And to be clear — the choice isn’t problematic on the level of an individual critic who wants to write aesthetic criticism. What’s problematic is the way that’s an either/or for ideologically minded critics, because the apparatus just isn’t there for them to readily talk about the “aesthetic” layer as anything other than aesthetics. It’s not impossible; it’s just a lot harder than it is for someone writing about a novel…

Matthias — I think that last comment maybe hits at what you were just saying.

I don’t think aesthetic criticism needs to be couched in theory. I think there is not enough theory for ideological criticism to grapple with these aesthetic things in the way you want to see them grappled with…ideological criticism needs theory in a way that aesthetic criticism does not.

That’s what I was getting at when I said it wasn’t a critique of this essay — I agree with everything you’ve said in your last comment there. It’s just that I think the problem of dealing with the visual for an ideological critic isn’t just a matter of attentiveness – it’s a matter of not having a wide range of ways to talk about it.

You’ve made this argument before, and I still don’t know that I’m convinced. There’s been a lot of theoretical ink spilled about art, too, surely, and about visual matter. There’s tons of film criticism, for example, which fits interestingly onto comics in various ways. Lacan has lots of things to say about images. I just don’t know that it has to be that much of a mystery.

Matthias, pointing to Wertham makes sense…but it’s worth thinking about how utterly discredited and loathed he is. There are reasonable historical explanations for that, and they certainly connect to why ideological criticism is still so mistrusted in comics as compared to other mediums. But the fact remains that ideological criticism is still mistrusted. I don’t think the conventional wisdom has changed that much.

I also think it’s important to point out that if HU has sunk into a swamp of ideological critique, I personally blame Matthias himself for spending his time with the new baby rather than writing for us more often.

Stupid babies.

But Matthias has specifically mentioned those writers, from Lacan to Rosalind Krauss, as examples of ideologically minded critics who do not pay enough attention to the visual. I can probably find the comment where he said Krauss in particular was too linguistic — and honestly, if she doesn’t get it right, I’m not sure any of us ever could — unless we just simply wrote aesthetic criticism INSTEAD of ideological, which I think isn’t Matthias’ point.

Lots of semioticians in particular talk about images — Lacan yes, but Barthes, all the psychoanalytic film people, probably it’s more normal for them to say something about images than not. But the way those writers and theoreticians talk about images doesn’t satisfy what Matthias is looking for. I think his critique of them is correct to a point — they talk about images but they do not talk about them in a way that is particularly able to grapple with their aesthetics or with the ways those aesthetics feed into the ideological terrain — it’s definitely a gap in the way that type of work approaches visual texts. And as a consequence, there is a pretty significant difference in the depth of ideological work done in linguistic contexts and the work done in visual ones – a lot of the claims made for and about visual texts by ideological critics aren’t backed up by nearly as thorough a logical or philosophical argument as the claims made for linguistic texts, especially when those claims are tied to technical elements. It’s not that it’s a mystery — it’s that aesthetic criticism and ideological criticism are, presently, fairly discrete things, one interested primarily in “a subjective sensation or experience that I have looking at his line, which may hopefully resonate with others,” and the other interested primarily in refracting the text or object through logical and philosophical lenses. Those logical and philosophical lenses have an indisputable linguistic bias that results in a particular outcome when we view visual texts through them. Part of that outcome is the exclusion of the sorts of sensations that Matthias is concerned with here.

I don’t think it’s “mysterious” but I also don’t think that it would be very straightforward to construct an equivalent in comics to, say, the kind of immensely detailed logico-philosophical argument that Derrida constructs for Plato or the one Althusser constructs for religion. Rosalind Krauss gets absolutely the closest I’ve seen anybody get, and if her efforts are still too linguistic, then I think it’s not much of a stretch to assert that the problem is with the theory, with how well the theory is equipped to resonate with visual aesthetics, rather than some simplistic failure of critics interested in that sort of stuff to pay attention. When the people who pay attention are getting it wrong, then there’s something else at stake.

I think part of it is that Matthias wants the “subjective” register engaged more directly, and I do think, Matthias, that you probably would not like the way ideological critics engage the subjective, because they will be so skeptical of it as a mode of “truth” in the way you suggest. But I think that doesn’t necessarily change the fact that aesthetics and physical instance are simply elided in much of that work, and it’s a fair charge. It’s just not one that can be solved effortlessly.

The penultimate couple of paragraphs in Matthias’ last comment are a good indication. Here’s the first one:

That’s a very fair aesthetic observation, and one that should be made about the work. However, how do you get from there to an ideological critique? How exactly does that observation play into the questions about Orientalism raised in Suat and Nadim’s posts? Ideological criticism requires those dots be connected, and connected in a way that ties into — either by illuminating or challenging — some particular understanding of ideology and how it works. Can anybody connect those dots in an interesting and original way, that speaks back to the functioning of ideology and the logics of visual aesthetics and representation? I think that’s a lot harder to do — not impossible, but harder. Those questions are at the stage of writing the theory of those visuo-ideological logics, not just applying something somebody else has already articulated.

Here’s another one:

And the same thing is true there — I don’t disagree that it’s possible at all. But how much thought has been put into exploring how it works? Is there a body of critical/theoretical literature on caricature comparable to that on the Gothic, or on the semiotic gap? I don’t think there is, so that work is what’s needed, where we are — and that’s why applied ideological criticism is so often unsatisfying: it skips steps, resorts to intuition (or worse, analogy with linguistic theory), and leaves the big questions unasked. Lacan, for whom subjectivity itself is structured like a language, is absolutely not an answer to that…

I think it’s important to specify that there are a large number of theories of ideology that need to be engaged — from the simple moralism of Werthem to the extremely counterintuitive structural marxism of Althusser. You could write a multitude of pretty length essays JUST ON THAT ONE POINT, about the way “wider representation” either feeds or mitigates the functioning of the ideological frame, because it would work differently for each ideological frame. “Wider representation” confronts moralism far more directly and effectively than it confronts an ISA. That’s what I mean by the theory isn’t there. It’s not even really there for fine art although it’s much better; it’s really not there for comics and “traditional cartooning.” And even then, “wider representation” is one remove from the formal aesthetic properties — there’s even less on how, say, the formal properties of caricature play into those ideological frames. Andrei’s comment the other day about political modernism being kind of bluntly displaced by cultural studies — that probably derailed a lot of it in art before it could get written, but I think it’s pretty indisputable that it got derailed…

ha ha good on you, Matthias

In terms of the limited range of linework in terms of ideology; I think you could argue that the thinness of the aesthetic range could be tied to the thinness of Orientalism itself. Orientalism is about rendering the East flatter — slicker, perhaps — than it actually is in order to make it more readily assimilable/consumable. The surface pleasures of Habibi could be seen as analagous to the way that Orientalism itself is a surface pleasure.

Similarly, in the Crumb discussion Matthias denigrates, one of my major points was one that was both formal and ideological; that is, that because racism is not as a system of thought in any way connected to or predicated on reality, visual exaggeration is not an effective mode of satire.

I don’t think those are especially difficult or unusual leaps? Certainly people make those kinds of connections in visual arts criticism and film criticism all the time. Domingos very deftly moves back and forth between ideology and form in his take on Contempt, for example.

Criticism is a prose genre, so any criticism is going to be linguistic. But there’s been tons and tons and tons of subtle and thoughtful ideological readings of visual material in the last several centuries.

Well, I’m not speaking here for Matthias, but I think that analogy would probably fall into a “linguistic” approach. But it’s more that it’s a pretty loose analogy. Is Orientalism really a surface pleasure at all – or is it just a symptom (synthome) of an ideology of racism and the Other (et al.) that actually lurks quite deeply, far beneath the surface of a culture? Or to go the other way, what’s the ideological impact of that analogousness, i.e., what is the mechanism by which that aesthetic “thinness” feeds the Orientalist ideology it’s aligned with? Is aesthetic thinness one of the mechanisms by which the ISA of comics culture (ha ha) creates this kind of work by reinforcing an ideological committment to certain types of repetition? I’m just not sure that the simple analogy there actually gets at the crux of the problems. So it’s not that it’s difficult or unusual, or even completely useless — but it’s not really a fully formed ideological critique either. I think maybe the fully formed ideological critique would, in fact, be pretty difficult and unusual — and would also probably start to show its grounding in linguistic notions of what ideology is and how it works.

My sense is that it’s not ideology itself that Matthias is objecting to, but to a kind of easy recourse to linguistic and conceptual frameworks for talking about visual things. I think that’s a fair critique. I’m just skeptical, especially if someone as rigorous as Rosalind Krauss is still too linguistic, that it’s possible to do what he’s asking for without just leaving rigorous ideological criticism behind altogether — either venturing into either aesthetic criticism or just making the argument by analogy — at least with the notions of ideology we have at present.

Caro, I think I agree with much of what you say, even if I’m uneasy about making Rosalind Krauss a punching bag here. She’s a critic I admire a lot and I do agree that she has done more than most to bridge the gap you’re talking about, even if I’m ultimately unsatisfied with a lot of her work.

I also agree with Noah, however, which makes me wonder whether there’s perhaps a problem with your premise: there’s plenty of good writing about visual art out there, but very little of it plays according to the linguistic rules you’re describing. This may well be a problem, and I do think you’re right that the simple fact that rigorous analysis is primarily linguistic makes it harder to use it to discuss something visual, than something which is also linguistic (prose, poetry, etc.). The problem for me here is that I’m not sufficiently familiar with the specific arguments or theoretical groupings you mention to engage fully.

You’re certainly right that not enough has been done to explicate how cartoon typology works, just as many other aspects of comics remain un(der)explored, and further that ideological criticism of comics has tended not to be particularly impressive. That was part of my point, although perhaps not quite clearly stated.

One thing that I want to add, however, is that I don’t believe that focusing on the ideological underpinnings of art should be the ultimate goal of analysis — to me it’s very much just *one goal of many. An important one, no doubt, but also one that, when invoked, tends to overshadow everything else.

This is why I’m perhaps a little contradictory here. Noah proposed a good way of seeing the superficiality of Thompson’s visuals as a reflection of his Orientalism; more basically, you could see it as a general enunciation of the work’s general failure to live up to its ambitions of complexity, its failed application of Eisner’s promise.

However, I don’t necessarily think that my discussion of Thompson’s line would necessarily be well-served by being pinned down in this way. Language in this case specifies something that works by a different logic. This is the logic I’m trying to get at.

Noah, re: Wertham. You’re of course right, though there has been some pretty compelling efforts to at least partly rehabilitate Wertham in recent years, with Bart Beaty’s book leading the charge. You’re also right that the majority of comics criticism and analysis is pretty hopelessly retrograde and could do well to pay more attention to the kind of iconoclasm I’m criticizing. My problem here, however, is with the next step; I find it more interesting to address problems in current criticism than in the staid, venerable mainstream reception of comics.

I don’t think you’re necessarily contradictory, Matthias — I think there are just several different committments here that are maybe getting muddled together in the category of “ideological criticism.” I think you get at it a little bit when you say “language in this case specifies something that works by a different logic.” For me, though, being grounded in linguistic theory and criticism isn’t quite the same thing as Noah’s point that “criticism is prose.” Theoretical discourse specifies several different layers of things — the observation that the theoretical discourse is itself prose is pretty meta. So much of contemporary theory is grounded in actual linguistics — the formal analysis of language. So it’s not just that the criticism is linguistic, or happening in language; it’s that analysis of the way language works determined and shaped the assumptions about how ideology works.

My comments are very much from the perspective of a person who is not all that interested in aesthetic criticism, who finds ideological and formal criticism more satisfying. That’s not to say that aesthetic criticism is bad by any means or even to support the dominance of ideological and formal criticism. But from my perspective, I think there’s a deeper insight in what you say — we need to be critical, at least in the sense of self-aware, about the ways in which the linguistic determinism that underlies the way we conceive ideology shapes the way we “read” visual art in potentially problemantic ways.

You’re making a challenge to something that is axiomatic in contemporary theory, even the work of Rosalind Krauss (who is my heroine and probably my favorite critic ever, no punching intended) — the assumption that everything, bar nothing, is a text and functions, at its most basic and fundamental level, like a text and, more importantly, as a text. Ideological criticism assumes that every work is, at its base, an ideological text. That underlies so much of the way we think about ideology — even ideology like Werthem’s, even the type of analogy that Noah put forward. The idea that the linework (or whatever) is not a text but something else — contemporary ideological theory is not equipped to deal with that.

But it’s not sufficient to say, then, that we shouldn’t do ideological critique, or to suggest that ideological critique can’t ever specify anything interesting or useful or insightful about visual logic (or whatever we want to call it. Of course there is a place for an aesthetic criticism, and I realize that’s a big part of your committment, of what you’re pointing to — making sure that aesthetic criticism isn’t abandoned or derogated. But there’s also a need for questioning, theoretically, to what extent and in what ways the visual register really does follow the textual logics of the linguistic turn, and if not, whether it is possible to replace those textual logics with visual ones and how that changes things. Because without that, you actually can’t do ideological criticism about that register except in those linguistic terms. That “different logic” you point to is occluded, or at least, unarticulated.

If what you’re saying is that visual logic can’t ever be articulated, I think that’s too radical a position. If what you’re saying is that articulations of art theory need to be sensitive to potential pitfalls in the linguistic turn, I’m completely behind that. But I think those potential pitfalls aren’t something that a lot of ink has been spilled over…

Maybe one of my favorite painters (and one of my favorite comics artists) is worth quoting: “If you can say it, why paint it?” (Francis Bacon). Barthes said that critics think with the artist (emphasis in the paraphrasing mine). I like that: I’m not trying to translate images into words (that’s not possible), I’m just creating something else…

Anyway, if all content is ideological all form is ideological too because, as we know, the latter can’t exist without the former. In the particular case of the linework in Habibi (and I’m not proud to say that I’m including myself in THU’s tradition of criticizing what one ignores) I would say that the expressive stereotyping is akin to the cultural stereotyping. Indeed, the expressive stereotyping is the cultural stereotyping.

I wanted to say “the former can’t exist without the latter,” but it’s the same thing, isn’t it?

Analogy is one of the resources of language; it’s one of the ways criticism works.

“But it’s more that it’s a pretty loose analogy. Is Orientalism really a surface pleasure at all – or is it just a symptom (synthome) of an ideology of racism and the Other (et al.) that actually lurks quite deeply, far beneath the surface of a culture? Or to go the other way, what’s the ideological impact of that analogousness, i.e., what is the mechanism by which that aesthetic “thinness” feeds the Orientalist ideology it’s aligned with? Is aesthetic thinness one of the mechanisms by which the ISA of comics culture (ha ha) creates this kind of work by reinforcing an ideological committment to certain types of repetition? I’m just not sure that the simple analogy there actually gets at the crux of the problems. ”

Well, it is an off-the-cuff blog comment. I think you do raise a number of interesting questions though.

I don’t know that I’d agree that racism is deep, exactly…? I think, in any case, that there’s a distinction to be made between ideologies of racism as deployed against African-Americans in the U.S. and the kind of argument Said makes in Orientalism (to the best of my ability to remember it.) It seems to me that Orientalism is really built on a kind of shallowness; it’s stories about people one doesn’t know, deployed, as I said, to make those people more comprehensible, more simple — shallower. It’s also specifically built in part on a vision of exotic beauty and otherness more analagous to misogyny than racism — which is why perhaps Thompson slips so easily into the kind of gazing that would make Mulvey gag. So yeah, I think you could do a reading that incorporates Matthias’ aesthetic responses with an ideological critique making links between Said and Mulvey. Not that said reading would be perfect or couldn’t be questioned, but surely even Derrida isn’t perfect.

And given that, I’m still not convinced that the issue here is that theory doesn’t know how to deal with visuals. Are you sure the issue isn’t just linguistic-turn theory being resistant to prioritizing the kind of aesthetic experience Matthias wants to talk about, whatever the medium?

Noah — You said: “Are you sure the issue isn’t just linguistic-turn theory being resistant to prioritizing the kind of aesthetic experience Matthias wants to talk about, whatever the medium?”

I think I’m sure — I don’t think it’s a resistance to prioritizing it; I think it’s a conscious and overtly articulated philosophical position that such aesthetic experiences are superstructural or derivative or symptomatic or epiphenomal of the more fundamental linguistic plane, that they are definitionally not “a priori.” The assumption is that those types of aesthetic experiences are ideological in ways that boil down to linguistic-at-root structures, and, especially for critics really steeped in that perspective, it’s not enough to just say that they’re not. I don’t think theory sees those aesthetic experiences as exempt from the “everything’s a text” linguisticism in any way, period.

I guess that’s why I’m arguing that aesthetic criticism and ideological criticism are separate — I’m fairly convinced by the linguistic turn, so I will likewise need convincing that visual aesthetics or the aesthetic register period or even visual imagery distinct from the deep language that structures consciousness and subjectivity and even existence in the linguistic turn can occupy the same structural and logical place that deep language occupies in Theory/Continental Philosophy and its offshoots. I’m very open to and interested in the idea that it can, though, and I’m certainly interested in the question of what insights would come from the exercise — I’ve always felt that the work from that tradition on images, even the Imaginary in Lacan, was less satisfying, less well teased out, than the work on text, and that the theories of subjectivity were at their weakest and least specific where images were concerned, so I find it a fascinating and fecund terrain. But the outcomes I’m looking for won’t be primarily aesthetic — they’ll just be less dismissive of aesthetics than I think the current theoretical edifice allows for.

And of course, I’m not really accounting for all the cultural studies stuff that’s so common now at all, and there’s tons of “ideological criticism” that comes from that perspective — I don’t find that stuff all that compelling either, really. Matthias’ critique maybe is meant to encompass both cultural studies approaches as well as the High Theory of Political Modernism, but I’m really only interested in the latter…

“Indeed, the expressive stereotyping is the cultural stereotyping.”

Yes, that says what I was trying to say much better.

Caro–how do you define “aesthetic criticism,” and how do you differentiate it from “formal criticism”?

Caro, I’m sure you’re right, and I definitely think that the pervasive linguistic turn-notion that “everything is a text” is stifling and has had an unfortunate, equally pervasive influence. As I’ve often written here, I don’t “read” images, and I “read” music even less.

The problem I have here is that I’m ultimately less interested in the kind of discourse you’re asking for than you are — while far from uninteresting, it’s marginal to most people’s concerns, it’s undeniably elitist and potentially hermetic. You’re asking for something very specific, with very specific prerequisites and therefore find most existing theory and criticism wanting.

While I can’t deny that it would be great if something met your challenge, and am quite intrigued by the potential for deep visual structure that you propose, I can’t help but wonder whether much of the good, extant writing on visual art and culture don’t already succeed in offering the enlightenment you seek, even if it doesn’t meet your criteria? As you say, the structure you seek comes from linguistics, and images don’t work in the same way. There’s plenty of good scholarly writing and criticism of images around, as Noah says.

Anyway, I think Domingos put it well when he wrote that “the expressive stereotyping is the cultural stereotyping”, but I think my concomittant point in regards to Habibi has been ignored somewhat: the book still has considerable qualities in spite of this. It’s not a disqualification in itself that it doesn’t succeed in what it sets out to do, or has certain ideological problems. This was really what initially led me to call the kind of criticism often practiced here as Puritan.

Andrei: I’ve got my definitions of these terms from this ongoing conversation with Matthias so they’re maybe not exactly right, but “aesthetic criticism” is concerned with this more subjective territory that Matthias describes in his comment above as:

Formal criticism can be extremely objective, so I’d make a distinction there. I think Matthias uses formal criticism in his aesthetic criticism, but he is concerned with questions that go beyond the scope of formal analysis. Distinct but not discrete.

Formal analysis can also be used in ideological criticism of course. I think it’s harder to use aesthetic criticism in ideological criticism, though, because of the status of the subject in ideology. Even moralizing critiques like Werthem are suspicious of subjective pleasure.

Matthias, to one extent your claims here are ones of differening interests — and aesthetics! I find more pleasure in complex theoretical or academic critiques than I do in the more intuitive aesthetic ones, although there’s of course useful information and valuable perspectives in the aesthetic ones. You find more pleasure in work that values and accounts for subjective experience. I think there’s room for both approaches.

I think the ways in which academic and intellectual discourse is elitist are more complex though. We’re having this conversation in an extremely public forum, that anybody can read. We’re open to conversations with people who are unfamiliar with the discourse, and we explain and provide sources and background. Yes, absolutely, theoretical discourse is something that will never involve the masses; it’s unlikely most people will even be exposed to it, let alone interested in it. But I question whether it’s actually quantitatively smaller than the people interested in comics, or dungeons and dragons or Pan Am the TV show. There’s an implicit mandate that the pleasures of highly educated people are somehow suspicious just because they are associated with a certain type of privilege. But the problem, I think, comes when the privileges that allow people access to those pleasures are policed — by economics or whatever. There is nothing inherently bad about intellectual discourse — there is only something bad about closeting intellectual discourse behind paywalls and ivory towers. I think, for that reason, it is at least as important for ideological/theoretical/intellectual discourse to appear in a forum like this as it is for discourses that are more accessible, if not more so. So while I’m completely behind your assertion that aesthetic criticism should not be devalued in any way, I’m also pretty committed to the idea that it’s not an either or. The hegemonies of critical discourse — what you’re describing, as well as the situation with political modernism being displaced by cultural studies that Andrei mentioned a couple of threads ago — those are things that happen mostly in academia. On the Internet, there’s ample room for both — the solution isn’t to stop some specific group of people from writing and caring about ideological discourse, but just to get more people to write other kinds of discourse, so that there is more of everything, period.

There’s definitely a lot of writing I consider good on visual art and culture, but I don’t know of any extant writing on visual structure that could quickly and easily start to replace the role that the “deep structure” of linguistics plays in Theory. Most of the writing that I think engages those types of questions embraces the linguistic turn. Do you have an example?

Caro wrote:

“I guess that’s why I’m arguing that aesthetic criticism and ideological criticism are separate — I’m fairly convinced by the linguistic turn, so I will likewise need convincing that visual aesthetics or the aesthetic register period or even visual imagery distinct from the deep language that structures consciousness and subjectivity and even existence in the linguistic turn can occupy the same structural and logical place that deep language occupies in Theory/Continental Philosophy and its offshoots.”

Martin Jay discusses this in “Downcast Eyes,” making the case that a lot of what we call theory derives its force in part from the suspicion of images and the visual, if not an outright hostility to them. He then argues that by extension, this work owes more to implicit ideas about visuality than it would care to admit, and that there’s soil to be tilled there.

As for aesthetics and the linguistic turn, WJT Mitchell makes the case for a visual turn in theory… The realization that all media are mixed media, and that a phenomenology of the image demands an approach to is attentive to the ways language (and out theories about it) is itself shot through with ideas about and instances of the visual that trouble the textual model.

Scholars (Mirzoeff, Crary, and others) are working at the intersection of language and the visual, and tracing how aesthetic and ideological critique intersect.

A the end of the day, visual cultures/studies makes a strong case for the notion that any theory that hews too closely to one model of representation/perception is going to elide important intersections between modes.

Nate, I haven’t read the Jay, but I’ll look it up! I’ve read Mirzoeff, though, and that’s cultural studies. Cultural studies, as interesting as it is, eschews the kind of modernist theoretical questions that were involved in shaping even the notions of ideology that cultural studies itself uses. So as interesting as their work can be, it just doesn’t get at what I’m calling “deep structure.”

Cultural studies work like Mirzoeff’s really doesn’t get there specifically because it’s too concerned with perception and culture. I mean, it’s overreducing but basically the premise of the linguistic turn is that perception itself is deep structurally linguistic. All perception. The only people who would be exempt from that would be feral children, who are hardly a good model for studying culture. I don’t think that’s hostile to images — I think it’s just extremely committed to language. Valuing one thing doesn’t mean you are hostile toward something else. (I think the emotional language here is also probably inappropriate…is that Jay?)

But “modes of perception” would be almost entirely irrelevant to the role language plays in those theories, because the deep structure of language is a priori to perception, not a facet of it. Visual perception is a posteriori. Those intersections between modes that cultural studies folks are concerned with are all happening inside a structure that is ultimately determined by language. (And to be honest, I think at least those cultural studies people who are really adept with Theory would acknowledge that — they just wouldn’t find the more “universal” structural questions of political modernism interesting or relevant; I think that’s largely Matthias’ point.)

It’s probably a problem that can be traced back to that comment Andrei made a few days ago about how political modernism was all-but-abandoned by the academy. All sorts of questions that were still pending in political modernism were just left unanswered and the status of the visual is one of them.

But the dilemma is that it wasn’t a total break. Political modernism and the theories of ideology it developed, which are slightly removed from the most overtly linguistic work of the Turn, are still underpinning and informing a lot of cultural studies. Academics working in cultural studies still rely very heavily on Althusser and post-Althusserian notions of ideology, but they often do it without any real rigorous understanding of the suppositions behind that notion. (Or they are ok accepting the premise and don’t worry about it.)

If you push on it, you still run into the primacy of language; the analysis of images is still refracted through that lens at some level. That’s what I’m trying to say in my initial response: people who do ideological critique using any contemporary theory, even cultural studies, assume the priority of language at some level, so what Matthias is asking for isn’t easy to do without just abandoning ideological critique altogether.

It’s not that there’s absolutely no engagement with political modernism — Andrei does it, Jan Baetens occasionally does it, I think Rosalind Krauss does it, much of what’s published in October sort of waves at it. But a systematic, collaborative, large-scale effort to engage the place of the visual in Theory — I haven’t seen any evidence that exists. Most academics just simply don’t write that kind of theory or ask those kinds of questions anymore — they all do cultural studies, because that’s what the academy rewards. So anybody who thinks theoretically in that way has their hands tied, because the foundation isn’t there.

Lacan is quite hostile to the visual, isn’t he? At least from what I can understand, he tends to denigrate the imaginary in favor of the symbolic, i.e., the visual in favor of the linguistic. And Lacan’s pretty important to the linguistic turn. I think suggesting the linguistic turn is hostile to images (and therefore in many ways Puritan) isn’t wrong.

I don’t think he’s hostile or that there’s any denigration. I just think he thinks we make sense of visual images via language.

It’s not that language is more important — it’s that everything is filtered through language. It’s inescapable, prior to anything and everything. No culture without language, period. It’s not like there’s a hostility to the images; they’re just secondary.

Yes, you’re right Caro, although language is clearly foundational, I’m interested in perception and cognition beyond it, if one might formulate that. I was also going to say Jay, although it’s been a long time since I read “Downcast”, and I remember a fair amount of Lacan in that book. Mitchell is good, but I’m not sure he does what Caro is asking for. And Crary, while very committed to the visual and quite original on it, is in many ways a disciple of late Barthes, thus linguistically schooled. A compelling alternative that I’ve found valuable, but in which I have only dabbled, is cognitive theory and neuroscience.

In any case, I don’t disagree with any of the things you wrote about academic discourse, etc., Caro, I was merely trying to explain my particular interest and to suggest that what you’re asking for is perhaps so specific as to be impossible, since it’s predicated upon a linguistic understanding of culture. I’m not sure.

Matthias makes a good point about the craft side of the book. The style is something like a Spielberg film isn’t it? Derivative, well crafted, nothing exceptional.

It’s quite retro looking and if judged on that basis could be compared to the comic book art of the past it aspires to.

If you found Thompson’s artwork in a 1950’s comic book, say a Dell Four Color Arabian Nights feature, it wouldn’t look out of place, and would look rather middle of the pack aside various stories by other artists.

I always space the cult studies/crit theory distinction, but I appreciate it. As for what critical theory posits about re. language epistemology and ontology, Jay does a good job at explaining why that’s the case, and of suggesting how it limits the stars goals of theory. Btw, have you (or anyone else on this thread) read Ranciere? I have only limited knowledge of his work, but it works back from theory to talk about aesthetics.

My husband is a neuroscientist — I couldn’t possibly be more skeptical of the value of neuroscience for the analysis of culture!

A big part of that, though, is that neuroscience is definitionally individual-oriented, in the sense of organism oriented. (There’s an interesting book on this called “The Evolution of Individuality” I think, that talks philosophically about the scientific concept of the individual.)

I think it’s limiting for studying culture, because culture is collective in some very important ways, and there’s a point where you have to recognize that the organism doesn’t scale. It’s not that organism-level insights are inaccurate or anything, but they don’t really lend that much insight into phenomena that are shared but not biologically determined. They can account for, describe, and call attention to biologically determined commonalities among groups of organisms, but they cannot account for anything that is truly independent of any individual organism — like culture, or language, or history. Those are aggregate phenomena for which biology is not a straightforward cause. It is a factor, in limited ways. But it only provides insight about individuals.

That’s, I think, getting back to this subjective/objective business again, whether questions of the interface between the culture and the individual are actually insights about the culture, or just insights about the individual.

Matthias, I think maybe I should make it a little clearer why I took this thread in this direction. Since we’re talking about theory, I’ll do it in a haphazard syllogism LOL.

1. “aesthetic criticism” as you use the term has a pretty strong subjective or individualistic component

2. “ideological criticism” is, definitionally, non-individualist, concerned with “the subject” of culture and discourse (even when it’s cultural studies)

3. the two things you’re looking at — individuals and visuals, are both subordinated to language and the collective in the formulations of ideology that underpin ideological criticism

4. in order to give images and aesthetics more weight in ideological critiques, as opposed to just replacing ideological critiques with non-ideological ones, we need a) a version of aesthetics that is attentive to a non-individualist subject and b) not more art theory but a new formulation of what ideology is and how it works, comparable to Althusser’s, that takes images more seriously.

I think we both agree with Nate that the status of images in the theories of ideology and subjectivity is problematic and limiting. I don’t, however, agree that it’s impossible to reformulate political modernist theories of ideology so that they are more attentive to images — they’re essentially heuristics, so they should be able to evolve. What I think it’s not possible to do is recast those so they are more conventionally “individualistic” or subjective, although there could certainly be some sort of dialectical movement there. It seems like maybe the problem you have with ideological criticism comes as much if not more from the radical decentering of the “individual”/subject as it does from the radical centering of language (and the related “hostility” to images), perhaps?

Ranciere is definitely working toward a political theory of the aesthetic that squares how visual art functions relative other categories. But as if to confirm Caro’s point, to do this he checks questions about individual uptake at the door, and focuses instead on the level of culture.

I haven’t read any Althusser and haven’t exactly been encouraged by what people have told me, but maybe I should try?

You’re right that my criticism and ideas about how most rewardingly to approach art has a strong subjective/individualistic component. Without that, there’s no ideology (which may not be individualistic, but is formed intersubjectively, no?). I guess in my more idealistic moments, my view of aesthetics and their importance is somewhat Kantian.

As for neuroscience, it does have to to with individuals, but also biology, which is something we all share, which again is why I find it helpful. In the present context, for example, it points to cognition beyond language, which is something I believe quite strongly in, as we’ve discussed before.

————————-

Caro says:

…For example, why, in general, does “nervous jumpiness” make you “wonder what meaning it holds” more than something more controlled? Why would control itself make something less meaningful? You seem to be saying that the form signals something very specific — but is it really the case that controlled work is always less meaningful than looser work?

————————-

Not so much less meaningful as more limited in that, in effect, it dots all the i’s and crosses all the t’s for the audience. (In the same way as does the use of stereotype: immediately telling us who is a hissable villain, a pitiful victim.) Which therefore inescapably circumscribes the range of reactions it can evoke. From his article:

————————–

Matthias Wivel says:

…the line is rather mechanical, incapable of surprising us – every stroke is in its place, and we know where it is headed. Compare Thompson’s other great paragon, Blutch, who for all his faults invariably retains a spontaneity of rendering, a reflexive laxity of control that enables surprise error and insight.

…Though less secure, often laborious, and marked by errors, {Nilsen’s] line moves with a nervous jumpiness that makes us wonder what meaning it holds, where it is going.

————————–

————————–

Caro says:

Or, when you say “He uses the same lines to delineate the curve of a sand dune and bodily effluvium,” why exactly is this a problem? We use the same words to write newspaper articles and poetry…I’m not saying it isn’t a problem, but it’s not self-evident that this is anything other than an aesthetic observation.

————————–

From “Understanding Comics”: http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/uc1-2.jpg .

Though one could understand Thompson’s not varying his approach within one book as drastically as that Rory Hayes/Charles Schulz example, he need not go that far to differentiate sand dunes from bodily effluvium. Regrettably, my copy of “From Hell” isn’t accessible to scan and post the pages in question. But there’s a sequence therein where the awakening rituals of the impoverished prostitutes and the wealthy Dr. Gull are contrasted; not simply in the details (the women are held up by ropes against walls, that they may be crammed together to sleep upright, while Dr. Gull enjoys a plush bed, the pampering attentions of servants) but in the texture and approach of the rendering itself.

While Eddie Campbell draws the situation of the poor in the gritty, scratchy pen-and-ink style most of the comic appears in, Dr. Gull’s morning is rendered in soft, flowing watercolors and washes, to create a visual contrast akin to that felt when touching a wire brush and then a velvet cushion.

—————————

There is a lot of criticism — but there is much less theory. Because theory is always generalized, not encased in a reading of a text or a work. And the lack of theory diminishes ideological critiques, makes it difficult for them to grapple with the visual issues you raise.

—————————

I think that the lack of theory in anything beyond the purely scientific realm would tend to be a strength. With appraisals not forced to fit the Procrustean Bed of being acceptable to the “generalizing” of theory.

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…Art in general, and comics in particular, has a long tradition of valuing imperfection over slickness….

——————————

With art, “valuing imperfection over slickness” is a relatively recent arrival in its ancient history (with only the Japanese having a long-time appreciation of deliberately rough-looking textures/finishes in, say, tea ceremony containers).

In alternative comics slickness may frequently be downgraded (though skilled rendering is far from infrequent); but in the rest of the field, polished art is the rule.

—————————–

… I think you could argue that the thinness of the aesthetic range could be tied to the thinness of Orientalism itself. Orientalism is about rendering the East flatter — slicker, perhaps — than it actually is in order to make it more readily assimilable/consumable. The surface pleasures of Habibi could be seen as analagous to the way that Orientalism itself is a surface pleasure.

——————————

Yes; Thomas Pynchon criticized tourism because it encouraged the shallow “consumption” of another culture as if it were a theme-park attraction, rather than a deeper exploration. Orientalism is like a “visual tourism”; catering to expected stereotypes and tropes.

In the fashion that all the old-time popular postcards and advertising imagery — aimed at a white audience — of happy, childlike “coons” slavering over watermelons or being lazily carefree form a body of, say, “Negrotalism”…

(Why, it’s R. Crumb’s fantasy! http://www.globalclashes.com/2006/08/the_image_of_th.html )

I think that the lack of theory in anything beyond the purely scientific realm would tend to be a strength. With appraisals not forced to fit the Procrustean Bed of being acceptable to the “generalizing” of theory.

Mike, this is from cognitive psychology, but there’s a reasonable theory of concepts called the Theory Theory, which suggests that we need “theories” to explain the relation between and development of concepts themselves. What’s called the Classical Theory (dating back to Aristotle) where concepts are merely lists of attributes (non-ideological, non-theoretical) has a lot of problems.

neuroscience is definitionally individual-oriented, in the sense of organism oriented.

Caro, the difference between studying biology and culture has to do with the proper level of analysis, but it doesn’t seem to me to be about individuals vs. groups. Any biological model that’s only about an individual is a failure, lacking replicability. It had better apply across a large number if it’s to have any sort of validity. Similarly, any cultural model ought to apply to the individuals involved. The problem is trying to reduce one model to the other.

cognition beyond language, which is something I believe quite strongly in

What Matthias said.

I think one possible issue here is that the thing that makes humans humans is (not absolutely, but quite probably) language. That is, the thing that defines humans as individually human rather than something else is in a lot of ways our ability to communicate with each other. That makes any effort to distinguish between individuals and groups in terms of analysis hopelessly muddled.

Charles — you said it yourself, though — the issue isn’t that it “applies to a group”, the issue is that it is reproducible. It’s axiomatic in population biology that a population is a group of individuals. Reproducibility is not “applicability to a group.” It’s “occurrence in multiple individuals.” The “group” is always a shorthand, not a valid unit in itself.

That doesn’t transfer over to culture, though, because culture is not, to paragraph August Weismann “reducable to a consequence of interactions among individuals within populations.”