Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) presents the story of the “Aden Arabia” collective, a group of five students from the University of Nanterre who have borrowed an apartment for the summer as a space where they can co-habitate according to the rigorous tenets of Marxist doctrine. The five students are Guillaume (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a flamboyant actor interested in revolutionary theater; Véronique (Anne Wiazemsky), Guillaume’s lover, a philosophy student willing to use terrorism to bring about revolution, and most likely the Mao-besotted “Chinese Girl” of the film’s title; Serge (Lex de Brujin), artist and eventual suicide; Yvonne (Juliet Berto), a proletarian from the French countryside who sometimes turns to prostitution (that old Godard theme again) to support the commune; and Henri (Michel Semeniako), Yvonne’s lover and the member of the commune closest to the French Communist Party’s brand of “humanistic,” non-violent socialism. (Henri is, in fact, eventually kicked out of the Aden Arabia cell for being too soft.) La Chinoise is loosely organized around four interviews that Guillaume, Yvonne, Véronique and Henri give, in that order, to an off-screen interviewer whose voice is sometimes audible on the soundtrack. The narrative of the film, fragmented though it is by Godardian digression, involves the students’ increasing acceptance of Véronique’s program of revolutionary violence. The results of this program are Henri’s expulsion from the commune because of his unwillingness to resort to terrorism, and Véronique’s murder of a man she mistakes for a reactionary Soviet politician. (Serge commits suicide to cover up Véronique’s culpability—before he shoots himself, Serge takes responsibility for the assassination in his suicide note.) The film ends with the apartment reclaimed by its bourgeois owners, as Véronique admits (in voice-over) that the Aden Arabia commune represented only “the first timid steps of a long march.”

“Godard : le plus con des Suisses pro-chinois !”

In many scenes at the beginning of La Chinoise, the students insist that their version of Marxism/Leninism/Maoism is better and purer than the revisionist cultural and political movements of the established Left. In the third shot of the film, Véronique proclaims that any trace of liberalism in the commune would “rob the revolutionary ranks of compact organization and strict discipline”—and soon afterwards Serge carries Henri into the apartment and tells his comrades that Henri’s been beaten by commandos from the French Communist Party. While Véronique comforts Serge, Guillaume says, “Being attacked by the enemy is a good thing, because it proves there’s a clear distinction separating us.”

But this distinction is more porous than Guillaume believes. Several critics note that La Chinoise portrays the students ambiguously, praising them for their enthusiasm even while revealing their dearth of workable ideas for political change. Pauline Kael describes the students of the commune as

infantile and funny—victims of Pop culture. And although [Godard] likes them because they are ready to convert their slogans into action, because they want to do something, the movie asks, “and after you’ve closed the universities, what next?” (Going Steady 84).

Further, the commune is also compromised by a rift between the students’ professed allegiance to Maoism and their actual everyday behavior. Although the students consider themselves revolutionary, the commune is a site where Yvonne—the member of the cell from the lowest social class—is saddled with the bulk of the household chores. Also, Godard goes to great pains to show that the students are ignorant of Marxist theory and infatuated with the distinctly non-revolutionary attractions of popular culture. These contradictions give new meaning to the film’s injunction to change the world “on two fronts.” In a key scene, Véronique and Guillaume listen to Serge lecture about the need to struggle on two fronts—the political and the aesthetic—to bring about revolution, but Guillaume claims that such a struggle is “too complicated.” Véronique then tests him by saying “I don’t love you any more” while playing romantic music under their conversation. After a few hints from Véronique, Guillaume eventually interprets these two “fronts” and realizes that the music is conveying Véronique’s love even as her words deny affection. Although the “struggle on two fronts” is clearly Godard’s take on his own fusion of aesthetics and politics (and the late-1960s Cahiers du cinema radical project), La Chinoise’s other dual discourse, the discrepancy between the beliefs and actions of the commune members, is likewise a coded message “on two fronts,” and those who decipher the code understand that the film is a highly critical portrait of the Aden Arabia commune and the revolution they hope to bring to life.

“Je Joue”

Much of the film’s ambiguity lies in the contrast between what Kael calls the “playful” natures of the young Maoists and their failed attempts at revolutionary action. The students borrow a bourgeois apartment for their cell; Véronique’s violent tactics are criticized by François Jeanson, a real-life leader of the Left known for his underground protest against the Algerian War; and Véronique’s fumbled assassination of the Soviet diplomat results in the death of an innocent bystander. As James Monaco writes, “It seems as if the Aden-Arabia collective is only playing at revolution, and they aren’t very successful, even at that” (The New Wave 189).

Godard undermines the students’ radicalism by showing how they enjoy playing with bourgeois popular culture. During a speech that Guillaume delivers to the collective, Véronique proclaims that “the soul of Marxism” is analysis that exposes contradictions, that carefully studies “the situation,” beginning with “objective reality and not from our subjective desires.” Yet despite Véronique’s outburst, the students persist in examining the world in simplistic, highly theatrical ways, using icons and products of popular culture that allow them to play more than analyze. At the end of his talk, Guillaume reduces the Vietnam War to clever sound bites, as he puts on sunglasses with lenses painted as national flags. When he puts on the American flag sunglasses, Guillaume attributes the War to the fact that the Americans say “Asia for the Americans.” Similarly, Russia’s denunciation of the War is simplified to “Do as I say, not as I do,” while France and Britain are called “on-lookers,” a term that elides the precedents these countries provided for America’s invasion of Vietnam.

Following Guillaume’s presentation, all the students participate in agit-prop performances with pop culture icons and children’s toys. Yvonne masquerades as a Vietnamese peasant threatened by both a massive picture of the Esso tiger perched on a gas tank labeled “Napalm” and toy planes that buzz around her on strings. To the sound of a machine gun firing, rapid editing alternates drawings of Batman, Captain America, and Sgt. Nick Fury. Henri wears a tiger mask and fatigue, declaring his support of peace even as he fires off a toy bazooka. And at the end of the sequence, a toy tank decorated with a tiny American flag is bombarded by dozens of Mao’s “Little Red Books.” Yet none of these acts contributes to their (or our) understanding of the War, and the commune’s appropriation of pop culture never rises above the obvious use of the Esso tiger and Captain America to represent first-world imperialism. Instead of the objective analysis Véronique considers “the soul of Marxism,” these performances simplistically reconfirm the commune’s opinions about the War, while allowing them to play with toys and dress up like Vietnamese peasants and American soldiers even as real peasants and soldiers die in Southeast Asia.

“La bourgeoisie n’a pas d’autre plaisir que celui de les dégrader tous.”

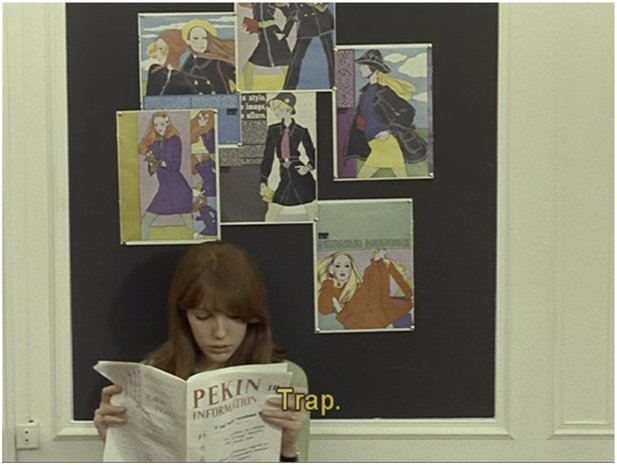

The film also hints that the women in the commune continue to take pleasure from certain types of decadent bourgeois popular culture. Briefly after the commune’s Vietnam performance, a single shot of Véronique exemplifies, according to Jacques Aumont, her strident Leftism, her interest in fashion, and the contradictory nature of the collective’s Marxism:

Anne Wiazemsky is shown reading a copy of Pekin Information (Peking News) in front of a billboard on which are pinned fashion drawings torn out of Elle. Immediately a powerful double discourse is set up because this single shot contains everything that represents the split between the character’s bourgeois class origins (fashion as a trivial exercise in taste) and a proletarian class position (at the least a voluntarist one). (91).

Aumont implies that Véronique is unaware of the nature of this “double discourse,” and professes hard-line Maoism even as revisionist popular culture infiltrates the commune. The other female student, Yvonne, experiences a similar lack of self-awareness later, in a brief scene that follows Henri expulsion from the collective. The scene opens with Yvonne and Guillaume in medium long shot, with Yvonne leaning against a wall and reading a magazine and Guillaume sitting and reading a copy of Mao’s Little Red Book. Amid brief flashes of other members of the collective, Yvonne and Guillaume chat. Yvonne says, “Listen this is fantastic,” and reads aloud from her magazine: “’The first date for Juliette and Pierre opened doors to a new world of magic, the world of words no one had spoken before them.’” Guillaume asks Yvonne what she’s reading, and grabs the magazine. She takes it back, and replies, “Henri gave me the party women’s magazine”—a publication of the French Communist Party and thus hopelessly compromised. Guillaume rips the magazine from Yvonne’s hands again, and reads aloud himself: “’Like the night before, their eyes met. Pierre couldn’t speak.’” He then says, “No point in being Communist to use that soap opera language,” and throws the magazine on the floor in disgust. Yvonne is annoyed with Guillaume, and when she calls the article “fantastic,” she expresses no sarcasm or mockery. We have several ironies here: after voting to banish Henri from the collective, Yvonne still reads one of his reactionary magazines, and the fact that she chooses an article about romance and courtship indicates both her longing for Henri and affection for romantic stories that is, by the standards of the Aden Arabia cell, dangerously retrograde.

“Une pensée qui stagne est une pensée qui pourrit.”

Another contradiction inside the commune involves the students’ shallow knowledge of Marxist philosophy. Although the members are supposedly eager for revolution, they have very little knowledge of Marxist doctrine, and their alternatives to capital are vague and uncertain. Guillaume is unable to define Marxist theater, resorting instead to examples to explain his drama. Early in his interview, he tells the story of a young Chinese actor protesting in front of the Chinese Embassy in Moscow; the actor wears bandages that disguise his face, and gets media attention when he cries out, “Look what they did to me! Look what the dirty revisionists did!” (In telling the story, Guillaume wraps bandages around his head too.) When the actor removes the bandages, however, he exhibits no scars, and the paparazzi are outraged. Guillaume notes that the reporters “hadn’t understood,” because the action was “real theater, a reflection on reality, I mean like Brecht or Shakespeare.” Yet it is questionable how effective such “real theater” is, particularly since the media wouldn’t cover this stunt. And Guillaume’s ability to recognize “real theater” is qualified almost immediately; as the off-screen interviewer asks him what constitutes a socialist theater, Guillaume replies “I don’t know. I’m looking…”—an answer that exhibits less certainty about the nature of radical theater than his anecdote about the Chinese protester.

Guillaume’s inability to define Marxist theater resurfaces at the end of La Chinoise, as the commune disbands and Guillaume brings radical theater directly to the public. Scenes of Guillaume’s “performances” alternate with placards that display, one word at a time, the phrase “The theatrical vocation of Guillaume Meister and his years of apprenticeship and his travels on the road of a genuine socialist theater.” (Guillaume is named after Wilhelm Meister, the actor and hero of Goethe’s two bildungsromans Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre [Wilhelm Meister’s Years of Apprenticeship, 1795-6] and Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre [Wilhelm Meister’s Years of Wandering, 1821]. Perhaps Guillaume’s summer with the Aden Arabia students was his apprenticeship, and he’s now begun his wandering.) Guillaume’s first activities include donning a fanciful 17th-century costume (the same Léaud would later wear in Weekend), posing on the street, and breaking up a bourgeois opera by yelling “I’m fed up with this job!”

In regular clothes, he then attends a performance of the “Theater Year Zero” in the basement of a dilapidated building; as part of the event, he is placed between plexiglass walls as a young woman in a bikini knocks on the wall to his left and an older, heavier woman in a bathing suit taps the right wall. (Guillaume looks at both and, predictably, smiles his approval at the pretty Left.) Later, Guillaume runs a fruit and vegetable stand, and sets himself up as a target behind a short, wooden wall as produce is hurled at him. Finally, while preaching Marxism door-to-door, he strikes up a conversation with a sobbing young woman who wants “revenge” against the boyfriend who has left her. The scene ends as the young woman confesses that she has “too much pain,” and Guillaume pauses for a moment before responding: “Enough, stop! It’s time to be logical.”

These scenes reveal Guillaume’s trouble reaching an audience with his radical theater. His disruption of the opera, for instance, strikes me as ineffectual, since the bourgeois audience would write him off as an annoying prankster, and ignore anything he had to say. Guillaume’s appearance at the “Theater Year Zero” may not demonstrate his own theatrical talents—he pays to get in and may only be a patron instead of a creative participant—but the theater’s performance addresses politics only in the facile (and sexist) comparison of the pretty Left girl and the ugly Right woman. Most damning, however, is Guillaume’s refusal to acknowledge and respond to the sorrow of the jilted woman he meets during his Marxist recruiting drive. Instead of offering sympathy, Guillaume dodges her feelings by retreating into the “logical arguments” of Marxist theory; he is unable to “struggle on two fronts” by giving the woman both compassion and Marxist propaganda. “The Education of Guillaume Meister” is a qualified success at best, and maybe he deserves the rotten tomatoes thrown at him.

“ Les armes de la critique passent par la critique des armes.”

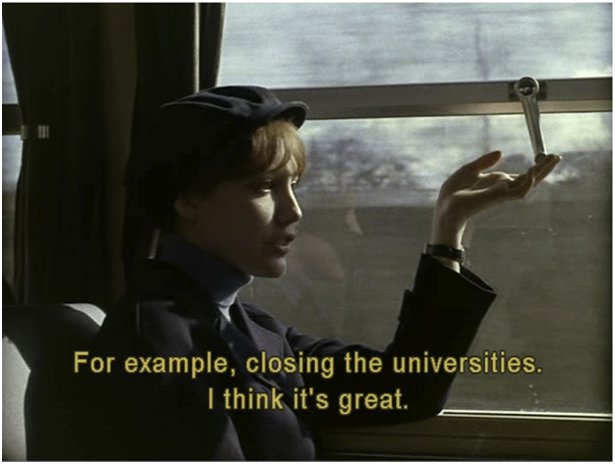

Like Guillaume, Véronique has a shallow understand of radicalism, and the limitations of her Marxist-Maoist beliefs are most thoroughly exposed during her very long train-ride dialogue with French Leftist and Algerian War protestor Francis Jeanson. At first, they talk about Jeanson’s writing, and his organization of a theatrical “cultural action.” Soon, however, their conversation drifts to Véronique’s plan to close the universities with bombs. Jeanson is sharply critical of her plan, insistent that violent insurrection needs a broad base of public support and should only be undertaken by a revolutionary who fully understand the situation. Jeanson then criticizes Véronique for having no idea of what will happen after violence shuts down the universities:

Jeanson: You only know the present system is awful, and you’re impatient to end it.

Véronique: Not awful, just bad. What we do after is not my work.

Jeanson: You don’t care.

Véronique: No, I don’t. After, I’ll continue studying the situation. I won’t stop.

Jeanson: Véronique, where will you study it?

The scene ends with Jeanson’s judgment that Véronique’s approach is “a path that leads absolutely nowhere.” Jeanson’s scathing critique is reinforced by the visual structure of the scene. Godard begins with a series of shot-reverse shots between them, and when Véronique is in medium close-up, we can see her softly fingering the window lever as if it were a penis, perhaps in a silent commentary on Jeanson’s patriarchal power brought to bear on her ideas.

Then the camera settles on a stationary framing which places Véronique on a train seat in the left side of the frame and Jeanson in frame right.

Behind them, through the window, French towns and farmlands pass by, creating a tracking shot of the French terrain while the poles of the French Left—Véronique’s extreme, violent approach and Jeanson’s Marxist humanism—debate the political future of the nation. Jeanson wins this debate, and his criticism of Véronique’s ideas is also La Chinoise’s most explicit criticism of the hypocrisies and defects of the Aden Arabia commune.

“Ne travaillez jamais!”

The film further presents the contradictions of the collective by showing that the commune’s chores are done by Yvonne. Near the beginning of the film, Véronique sits at a desk and takes notes while listening to Radio Peking. We see Yvonne’s hand enter frame right to dust a lampshade and, after a brief pause, enter frame left to dust the radio; Yvonne then leans into the frame to give Véronique a kiss, after which Véronique smiles. Later, as Henri speaks to the students about the social sciences and their role in the revolution, Yvonne washes the apartment’s patio windows. In this scene, Henri is criticizing certain social sciences that consider society’s faults part of a system that “men’s wills and projects cannot change,” yet for all his talk of change, he and the others stick to the sexism and classism of bourgeois society. None of the male students is ever shown dusting or washing windows; Yvonne, the woman from the poorest is most rural backgrounds, does almost all the work.

At the beginning of her interview, Yvonne unconsciously reveals the similarities between her work duties in capitalistic society and her work as a member of the commune. She describes the farm where she was born, and her regimen of everyday chores, including building the fire, milking the cows, washing the dishes and the laundry, collecting the eggs from the chicken coop, and cooking lunch and dinner for her family. Yvonne then notes that she moved to Paris and got a job cleaning apartments. When asked by the interviewer if she likes living with the collective, Yvonne responds,

It’s nice here on the top floor. It’s well-lit, airy. You know, I used to work near Passy. Then around Auteuil in those big bourgeois apartments, on the first floor. It’s always so dark. I had to sweep in the dark. Already the metro was dark. So I went from one darkness to another. It was always black. Then at night, I had to go back into the darkness of the metro. Whereas here, they discuss and talk. It’s very clear for me.

Her shift from “dark” to “clear” indicates her support of Marxist ideas, but Yvonne especially likes living with the commune because the apartment is bright rather than dark. There is no mention of work in her response, although her life before La Chinoise consisted of grueling, unappreciated rural and domestic labor. Yvonne does not, in other words, describe the commune as a place where work is more fairly distributed and she is expected to do less of it. It seems that she does as much work in the apartment as she did on the farm or in the apartments; there’s been no decrease in the burdens of her class position.

Between Guillaume’s and Yvonne’s interviews, a brief scene illustrates how the Aden Arabia members are blind to the fact that Yvonne does all the work. Henri, Véronique and Yvonne are in the kitchen, and the women are doing dishes. Henri picks up a newspaper and walks over to Yvonne, who is standing at the sink. He gently hits her on her head with the newspaper, says “I’ll go with Serge,” and exits the frame. Yvonne answers, “Don’t I get a kiss? You said we’d go see 8 1/2,” but Henri doesn’t return. Yvonne then asks Véronique, “Why does he always leave when I want him to stay?” Véronique replies, “Because politics is the starting point of politics, as well as the starting point of every practical revolutionary action.” Yvonne says that she doesn’t understand, and the following dialogue takes place:

Véronique: Now listen carefully. It’s easy. All revolutionary party action is applied policy. If you don’t apply a just policy, then you’re applying a false policy. If you’re not applying it consciously, then you’re doing it blindly. And these dishes, for example, why are you cleaning them?

Yvonne: So that they’re clean.

Véronique: Then you’ve totally understood.

Yvonne: So France in 1967 is a bit like dirty dishes.

Both Véronique and Henri treat Yvonne condescendingly in this scene. Henri leaves without worrying about the plans he had with Yvonne, and seems perfectly content with a relationship that allows him to withhold kisses and leave the house while she does the dishes. The “Don’t I get a kiss?” comment and the unfair division of labor makes their relationship uncomfortably similar to the traditional husband/wife dynamics of the bourgeois family—complete with newspaper!—and when Yvonne questions this relationship, Véronique responds with empty jargon.

Véronique also asks Yvonne “Why do you wash those plates?” but refuses to analyze either the question or the situation between herself and Yvonne. In Véronique’s question, the “you” referring to Yvonne is key, since examining why Yvonne is the dishwasher might lead to insight about the distribution of work among the commune members. Véronique instead focuses on Yvonne’s answer—“So they’ll be clean”—and the women make a simplistic comparison between France and dirty dishes that does nothing to improve the collective. Although Véronique calls for a Marxism of singular purpose and “conscious,” meaningful actions, she just blindly replicates old capitalist injustices.

“La passion de la destruction est une joie créatrice.”

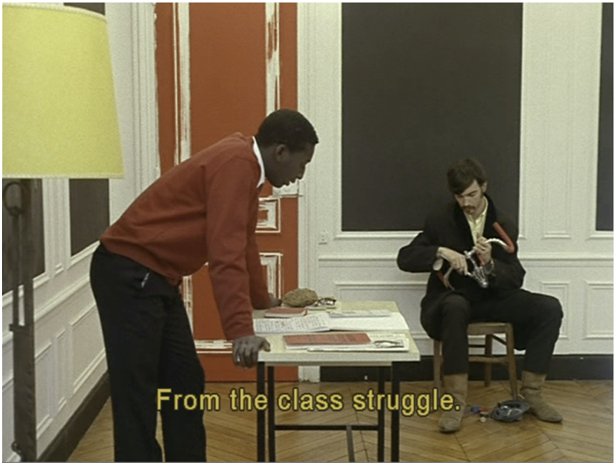

Yvonne is also the focus of a tracking shot early in the film that displays many of the unconscious dishonesties of the collective. This shot occurs after the interviews with Guillaume and Yvonne, when a philosophy student named Omar gives a presentation on Stalin and modern Marxism to the students. Before the camera moves, Omar asks the students, “Where do just ideas come from?” and receives the following answers:

Yvonne: They fall from the skies.

[Guillaume yells loudly, mocking Yvonne’s answer.]

Omar: No, they come from social interaction, and…?

Véronique: The fight to produce.

Omar: Yes, and then…?

Henri: From scientific experiment.

Omar: Yes, and what else? [Pause.] From the class struggle.

This dialogue is taken almost verbatim from “Where Do Correct Ideas Come From?”—a passage written by Mao as part of a report on rural work issues by the Chinese Communist Party in May 1963:

Where do correct ideas come from? Do they drop from the skies? No. Are they innate in the mind? No. They come from social practice and from it alone: they come from three types of social practice: the struggle for production, the class struggle and scientific experiment. It is man’s social being that determines his thinking. Once the correct ideas characteristic of the advanced class are grasped by the masses, these ideas turn into a material force which changes society and changes the world. (Mao, Selected Works Volume 6, 405)

The way Mao’s quotation circulates among the students serves as another example of La Chinoise’s double discourse. Each student hesitates before answering Omar, and when they do talk, they all miss the answer that would be most obvious and important to Marxists—that “correct ideas” come from the class struggle.

The tracking shot following this exchange uses camera placement and dialogue to take this double discourse further. During this shot, the camera is located on the balcony of the commune’s apartment, tracking back and forth, passing the outside wall, and frequently stopping on three open balcony doorways through which the people inside the apartment can be seen. Omar says, “Some classes are victorious, others defeated. That’s history…” As Omar speaks, he and Serge are in the frame.

The camera then tracks right as Omar says, now off-camera, “…the history of all civilizations.” As Omar finishes his sentence, the camera stops, creating a composition which includes a red door on the left side of the frame and Henri, Guillaume and Véronique on the right, among large piles of Mao’s Little Red Books.

While the camera remains on this shot, Guillaume asks, “Will class struggle end under proletarian dictatorship?” Omar answers “No” and launches into an explanation illustrated with an inserted photo of a Russian worker. The camera then moves right again, stopping at the next doorway to create a third composition. In this shot, frame right is dominated by a red balcony door while the left side features Yvonne, who is polishing shoes near a pile of Red books.

As Omar mentions Lenin in his explanation, a drawing of Lenin flashes on screen, and then we return to Yvonne in the doorway. By using these doorways to divide space, Godard separates Yvonne from the other students, stressing how her limited education and poor background make her different from them. She is shining shoes while the others are taking notes on Omar’s presentation—another reminder of the unfair division of housework inside the commune. And Yvonne’s segregation underlines Omar’s answer to Guillaume: clearly socialism—or at least the type practiced by the Aden Arabia cell—won’t end the class struggle.

The camera then rapidly moves left, back to Omar as he says, “Lenin showed class struggle doesn’t disappear under proletarian dictatorship, but takes on other forms.” In dissecting space to express the differences between Yvonne and the other students, this tracking shot once again backs up Omar’s arguments: the “other forms” of class oppression in the commune combine Maoism with the old specters of sexism and bourgeois class stratification. The track pauses as Omar continues to speak, criticizing the “duo Brezhnev-Kosygin” as the images quickly alternate between photos of young revolutionaries and isolated groups of letters from the title of the magazine Cahiers Marxistes-Leninistes. (The entire title appears at the end of the scene.) As Omar advises, “Give up illusions, and prepare to fight,” the camera moves again, sweeping past the second doorway and allowing us to glimpse Henri rising to his feet. The track stops when it reaches the third doorway, and we see Henri walk into the frame and kiss Yvonne.

Omar says, concurrent with the kiss, “This world is as much yours as ours. Hope lies within you,” encouraging all the commune members to renew their commitment to communism. Yvonne continues to shine shoes as Omar intones, “To work is to fight, and you must seek truth in the facts” and the camera moves to frame Véronique and Guillaume. Véronique asks, “But exactly what is a fact?” Then the camera moves for a final time, slowly returning to Omar, who answers that “Facts are things and phenomena as they exist objectively. Truth is the link between things and phenomena, which is to say the laws that govern them. To research is to study.”

The connections between Omar’s speech and the movements of the tracking shot illustrate the tensions between the students’ commitment to Marxism and their replication of bourgeois behavior. Although Omar’s words are meant for everyone in the commune, the track acknowledges Yvonne’s isolation by combining “This world is as much yours as ours” specifically with the shot of Henri and Yvonne. The “yours” and “ours” indicate the class gap between Yvonne and the rest of the students. Perhaps Henri becomes aware of the gap and tries to bridge it with a kiss. Yet this kiss repeats the patterns of patriarchal domesticity, creating a tableau where the “wife” does the chores and the “husband” dispenses affection according to his whims. And if “to work is to fight,” then Yvonne is the only one fighting in this scene; Henri walks off-frame after kissing Yvonne—he doesn’t help with the shoes—while the others ignore Yvonne completely.

“L’art est mort. Godard n’y pourra rien.”

Later in La Chinoise, Godard uses a tracking shot to dramatize the conflicts that split the cell. While giving a speech to the others, Henri is framed, like Omar, in profile, facing right, and standing behind a table. As Henri argues that “violent revolt and barricades can occur in advanced capitalism,” the students noisily object as the camera moves to a position in front of the second doorway. The dominant figure in this new framing is Yvonne, who has moved very close to the camera and looks out the doorway as she chants “Revisionist! Revisionist!”

After his expulsion from the cell, Henri relates a tale about Egyptian children to explain the activities of the Aden Arabia commune:

The Egyptians believed their language was that of the gods. One day, to prove it, they put newborn babies in a house far away from any society, to see if they would learn to talk. To talk Egyptian alone. They came back 15 years later. And what did they find? The kids talking together, but bleating like sheep. They hadn’t noticed that next to the house was a sheep pen. For us, in that apartment, where we were, Marxism was a bit like the sheep.

Henri is right: the students bleated the form, if not the substance, of Marxist doctrine. Yet La Chinoise shows that other sheep noises undermined the cell, most notably bourgeois popular culture and lingering sexism and class prejudice. It’s easy to play at being Marxist, but hard to change the world.

______________

The index to the Godard roundtable is here.

Craig, at the risk of derailing us into biography, I’m curious if Godard ever talked in this period about his opinions of the nascent student movement or the complexities of French leftist politics before ’68. This film is just so ambivalent — and yet Dziga Vartov is only a year later. I know the Langlois affair et al. changed him — but what exactly changed?

I thought the title referred not to a character, but to the entire collective, a “Chinese collective.” I think Chinoise was used to refer to such a collective at the time (it may have been a very limited usage).

Also, the full title is “La Chinoise, ou plutôt à la Chinoise,” –“La Chinoise, or rather in the Chinese manner.”

I think I’d sort of assumed “a la chinoise” without really being conscious of it. But here’s what Senses of Cinema says:

I’m not sure Senses of Cinema is authoritative on this. I definitely remember the explanation of “Chinoise” standing in for “collective,” but that’s from when I was studying film in college, over two decades ago, and I don’t have an exact source. If I’d thought it referred to just the one character I probably would have read/interpreted the film quite differently (by focusing on her to the exclusion of others).

Kind of along the same lines, see here: http://notcoming.com/reviews/lachinoise/

‘In a sense, then, the students themselves are the titular characters, “the Chinese,” a collective identity they imaginatively adopt in order to distinguish themselves from the members of a society they despise, who they understand, implicitly, as “the French.” ‘

So I guess it’s a collective singular noun? It seems like at least it would mean both, the one character, the collective (as well as the cacophony of la chinoiserie?)

I guess I’m asking whether you think there’s one definitive translation, or whether all of them are simultaneously in play.

We’ve seen a precedent for the ambiguous gendered title in Godard’s work before: the “her” in 2 OR 3 THINGS I KNOW ABOUT HER is supposed to refer to both Marina Vlady and Paris, right?

Good reminder about the complete title of LA CHINOISE, Andrei.

Caroline, I don’t have any insights about Godard’s radical conversion beyond what’s available in sources like Brody’s biography. His “coming to Mao” moment appears to have been caused by various factors–the Langlois Affair, May ’68, the influence of Anne Wiazemsky in his life, etc.–and personally I think it had a horrible effect on his art: I find movies like BRITISH SOUNDS and LETTER TO JANE a real chore to watch. What do you guys think?

I don’t know, to my ear the whole reference to “c’est du chinois,” “chinoiserie” sounds kind of iffy, but *maybe* it was intended… But, in general, sometimes translators (especially when doing theory!) tend to have fits of what I might call dictionaritis, assuming that all or most meanings listed in a dictionary were intended in some writer’s or artist’s usage of a word. However, more often than not the context, history of usage, intended level of discourse, addressed group, etc., tend to limit such extensive polysemy.

So…the coming to Mao is after the cultural revolution, right? Did people just not know that Mao was a tyrannical thug? Did they know but not care? How did that work?

I think they didn’t really know, especially naive bourgeois students. They may have just been following Althusser, whose revision to the base/superstructure has some roots in Mao (and who was also kind of a thug).

But I also think a lot of it was just completely internal French Left politics — opposing the establishment, and Mao wasn’t the establishment. It started before the cultural revolution, in ’62-3, with the Sino-Soviet split and had a lot to do with distinguishing oneself from various establishment parties and, eventually, from de Gaulle. (There’s an interesting clip of Anne Wiazemsky talking on the DVD of La Chinoise about the deterioration of Godard’s relationship with her grandfather after ’68, when he decided anybody who supported de Gaulle should be “shot” — she emphasized the scare quotes later, as if she thought saying that was disloyal LOL.)

It’s hard to find good histories of French party politics in English online, but maybe this is not so bad: http://www.isioma.net/sds00500.html (I didn’t fact check it, and I’m not strong enough on the actual history to do it without homework — maybe Andrei or Craig is…)

Oh, AW also talks in that clip about how bad those Dziga Vertov films are, so she’s disavowing any responsibility, Craig!

I think that’s one of the reasons why I’m more interested in that period biographically than artistically — it was a very interesting time. But I think Godard was busy living in interesting times, rather than making interesting movies.

I had told Craig I was going to include the movie’s trailer with this post, and I forgot. I’ve added it at the end, after the link to the roundtable index. It’s GREAT.

“personally I think it had a horrible effect on his art: I find movies like BRITISH SOUNDS and LETTER TO JANE a real chore to watch. What do you guys think?”

I’ve only seen “Letter to Jane” once, so I can’t trust my memory on it but “Tout va Bien” was fine. It’s those in-between films after “Weekend” that are failures. Even Godard has agreed with that consensus. The way he put it on how he got out of that blind alley- the films other Maoists were making were so terrible that it became a wakeup call for him in changing his point of view.

As for the films in the wake of “Tout va Bien-” I haven’t gotten into the daunting Numero Deux as of yet, but “Ici et Ailleurs” is excellent. Too bad youtube deleted it.

So much to comment on…!

Caroline, your mention of Althusser is right on the money: his ideas were in the air during the ’69 upheavals, and he’s directly cited by Leaud in LA CHINOISE–Guillaume mentions “a text on Brecht by Althusser.” (And now I’ve got to get LA CHINOISE back from Netflix and watch that interview with Wiazemsky…)

Noah, my sense is that both the European and North American left embraced Maoism as a vibrant radical alternative well into the 1970s–probably because the truth about the atrocities of the Cultural Revolution weren’t yet well known, and because Mao’s militancy were appealing to a Left that increasingly fractured as the ’70s ground on. My favorite book about this topic is Jan Wong’s RED CHINA BLUES, which chronicles her migration from Canada to China in 1972 to join the great project, and her subsequent disillusionment with Mao and Chinese communism.

Steven, I like TOUT VA BIEN too, but it’s not exactly a “Dziga Vertov” film. Casting stars like Fonda and Montand was Godard/Gorin’s attempt to reemerge from the underground and regain an audience. Also, according to various sources, TOUT was made after Godard’s motorcycle accident, and mostly directed by Gorin. It’s not really a communal film at all, and better for it, in my opinion.

And then there’s the fact that in the 1980s Godard claimed that he “never believed” in Maoism, even when he was directing agit-prop like WIND FROM THE EAST!

The clip with Wiazemsky is pretty brief, not a lot of detail, but interesting. I thought maybe it would be on youtube, but no such luck. I’ll try to find a couple of minutes to transcribe it.

Julia Kristeva in particular was at least somewhat complimentary of the Cultural Revolution as late as ’74 — she felt it was able to quickly redress gender injustices in China, really horrific gender injustices, like foot binding, in a way that slower, less aggressive cultural change could not. I don’t actually know whether she felt that justified its oppressiveness or whether she tempered her approval after the atrocities became better known. The quip about Madame Mao being the most successful fashion designer in history, dressing 700 million people — that’s still pretty funny.

Interview with Anne Wiazemsky

December 1987

Interviewer unknown

Transcript of subtitles on Criterion DVD

Interviewer: How was the relationship between your grandfather Francois Mauriac, who was a Gaullist, and Jean-Luc Godard, who was a Leftist?

AW: Until 1968, it was always very good. First of all they had only one encounter, but when Francois Mauriac learned that I had a liaison with Jean-Luc Godard and that I was considering marriage he was curious to meet him. And he asked me —

Interviewer: he didn’t know him?

AW: No, he had never seen any of his films. One afternoon, we went to see Breathless together in a small theater on the Champs-Elysees.

Interviewer: Francois Mauriac and yourself?

AW: Yes. Which is something I consider to be marvelous. this old man who suddenly says in the middle of the afteroon, “you love this man. Let’s see what he’s about.” And he found the film to be remarkable. He was rather proud of my choice in fiance.

Interviewer: So after 1968 their relationship degraded?

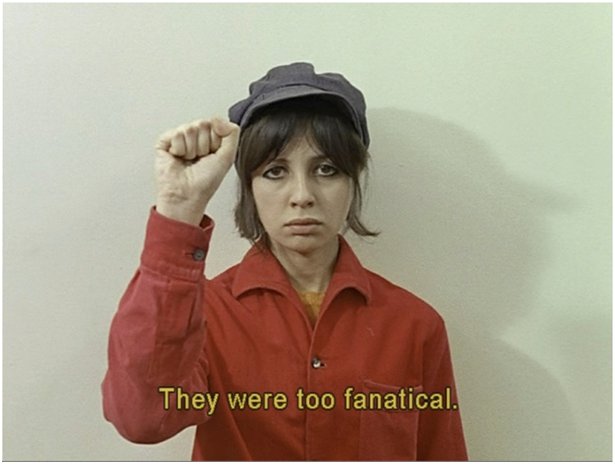

AW: Yes, it degraded due to Jean-Luc. Francois Mauriac was very tolerant towards others who weren’t Gaullist, plus he had the wisdom of his years. As he would say he pardoned the excesses of youth. As opposed to Jean-Luc, who at the time was a fanatic. He felt that all who were for de Gaulle should be shot. So if there was a rupture in their relationship, it originated from Jean-Luc who was very intolerant.

Interviewer: Was Jean-Luc trying to convince you that all who were Gaullist should be shot?

AW: When I say “shot” [smiling] I emphasize the quotation marks.

Interviewer: Of course, so do I. But he was —

AW: A terrorist? Yes.

Interviewer: And yourself?

AW: Mildly, very mildly.

Interviewer: Were you in agreement with him though, or not?

AW: Frankly the works of Mao Zedong, Marx and Englels are really dreadful. But every now and then I had to read them, because

Interviewer: Did you read out of love? Or professional consciousness?

AW: Professional consciousness, definitely not. Out of love, yes. It may sound stupid but that was the reason. Because it’s true that it wasn’t my favorite kind of literature.

CUT

Interviewer: In your opinion, which is the best film that you’ve made with Jean-Luc?

AW: La Chinoise

Interviewer: Without hesitating?

AW: No hesitation whatsoever.

Interviewer: Why?

AW: Why?

Interviewer: For what reason?

AW: First of all, I haven’t made that many films. As I’ve told you, I think One Plus One is a failed film, and as far as the others — I did do a scene in a film I really liked. It’s called Weekend. There’s a beautiful shot which happens in the courtyard of a farm, where Paul Gegauff is playing a sonata by Mozart, on the piano, called The Chase, and I walk past with Michel Cournot. The shot is incredible. So there’s that one film. But otherwise, the films that were made by the Dziga Vertov Group. [pfft.]

The best filmic period of Jean-Luc, in my opinion, stopped with Weekend and restarted with, maybe, Every Man for Himself, but definitely with Passion. Everything in between bores me, including those that I made. Including France/tour/detour/deux/enfants. They are all films that bore me, which may come as a shock to you.

Interviewer: [unintelligible, not translated]

AW: Maybe because I haven’t seen them since. With retrospect I might have the opposite opinion and now think them wonderful. But I doubt it.

Interviewer: But La Choinoise, it’s you that —

AW: Listen, Dziga Vertov was pretty much nonsense, because there was Jean-Luc, and Jean-Pierre Gorin, but surrounding them were people who hung around like decoration, so that it appeared to be a group. Otherwise it would have seemed like the films were made by the Dziga Vertov pair, the pair being Jean-Luc and Jean-Pierre Gorin. There was me; Armand Marco, the DP; Isabelle Pons, the assistant, a friend of Gorin named Nathalie I think, plus others who came and went. In brief, they were there for decoration around a pair of filmmakers.

CUT

AW: La Chinoise, not only was it a prophetic film but it’s also like a Marivaux comedy. And it’s a marvelous film which deserves to be viewed again. The grace of youth permeates throughout the film. They’re very young people, transitioning from children to adults. They’re almost exactly like Les Enfants Terribles. It’s really a film to see again.

Interviewer: At the time, did you live like some “enfants terribles”?

AW: No, I really love the film, but the shoot was very difficult, because I couldn’t tell when the work ended and our private lives began. For example it was shot in the apartment where Jean-Luc and I lived. Meaning, in the morning, before the crew arrived, I had to make the beds in case we were going to shoot in the bedroom, which was often the case in fact. So there was this mixture of things. One night I had a fight with Jean-Luc, and the next day, the scene was recreated nearly word for word, but with Jean-Pierre Leaud. And I was in an intense state of paranoia. I felt as though the crew knew we had fought the night before. Of course, they didn’t really care, but in my mind…in addition, I had a terrible complex about being the woman after Anna Karina, who was so beautiful and wonderful. And I would look at Godard, thinking he must find me ugly compared to her. I lived in this very paranoid fashion.

Just a few points. It doesn’t seem accurate to me to describe all the members of the “Aden Arabia” collective as being university students. It seems to me that only Véronique and Henri are represented as being students. Guillaume is an actor, Yvonne is a maid and occasional prostitute, and Serge is an artist. Omar, who lectures to the commune, but apparently is not a member, is also a university student too. Véronique and Guillaume are clearly the driving forces behind the commune, with the others more or less passively following the dictates of Véronique and Guillaume. Also, you write that Henri said that “violent revolt and barricades can occur in advanced capitalism,” when I think you meant to write that Henri was asserting that these things CANNOT occur under advanced capitalism. That’s the assertion that the rest of the commune rejects and he is expelled on that account.

As I recall, Henri was beaten up, not by members of the French CP, but by members of a rival Maoist group, based at the Sorbonne. As to the meaning or meanings of the term “Chinoise”, I certainly would agree with Colin MacCabe that Godard intended it to have multiple connotations, but as I understand it, it was among other things a slang name reference to Maoists in France at that time.

Other things worth noting: Anne Wiazemsky, like her character, Véronique, really was, at that time, a philosophy student at Nanterre. And Francis Jeanson was, in real life, her philosophy professor. And she was, at least peripherally, involved in radical politics at Nanterre. In the famous scene where Véronique debates her advocacy of terrorism with Jeanson, according to McCabe’s book, Godard was feeding Wiazemsky her lines, including her responses to Jeanson’s questions, through an ear piece that she wore for that scene. So, in reality the debate between Véronique and Jeanson was really a debate between Godard and Jeanson!

Jim, thanks for your corrections–and I apologize to you (and to other HU readers) for making those mistakes in the first place. (I can’t BELIEVE I called Yvonne a university student, when a substantial part of my post is about her status as a menial laborer, both outside and inside the collective..!)

Judging from your comment, you’re very familiar with McCabe’s biography. Have you read Brody’s book? If so, what do you think of it? Which do you find more accurate/useful, McCabe or Brody?

I have read both books but I think I would have to be much more familiar with whole body of Godard’s work before I could be confident to make a judgment of whose book is better. Concerning La Chinoise, I have not seen the DVD, but the film had been formerly posted in its entirety on YouTube, so I was able to see it several times – each time seeing details that I had missed in my previous viewings (while undoubtedly still missing many more). For example, the visiting Soviet Minister of Culture, who Véronique seeks to assassinate, bears the name of Mikhail Sholokhov, like the author of the novel And Quiet Flows the Don. In fact the real Sholokhov did serve as a kind of roving goodwill ambassador for the USSR during the 1960s (so it would not have been implausible for him to speak at a university opening in France like his fictional counterpart does in the film), but he never held the post of Minister of Culture.

Other interesting aspects of the film is that at least some of the actors were playing roles that were at least loosely based on their real lives. Anne Wiazemsly was at the time a philosophy student at Nanterre. Jean-Pierre Léaud, was, of course, an actor, and Michel Semeniako had actually been a science student at the University of Grenoble. The character, Omar, was played by Omar Diop Blondin, who was from Senegal and at that time a student at Nanterre, where he had developed a reputation as a black militant. In 1968, he played a leading role at Nanterre in the unrest of 1968 and as a consequence was expelled from France. He then returned to his native Senegal where with his brothers he helped to found a Maoist political party. Eventually, the Senegalese government cracked down and he wound up in prison where he died in the early 1970s, with the government claiming he had committed suicide and his supporters in both Senegal and France claiming that he had been murdered by the Senegalese government.

Having just watched the movie again for the first time in over two decades, here are a few observations that I want to jot down before I forget.

First of all, in response to Jim, it is clearly specified that Henri was beaten up by the “PCF.” Also, in the extras Godard does explain that each character basically played who they were in real life–Leaud, an actor, plays an actor, Anne W., a philo student, plays a philo student, etc.

Thirdly (and this is where being older helps–one catches a lot more references)–the film is full of references to French history and culture. Leaud does not dress in a “seventeenth century costume” (tsk tsk!) but in that of a French revolutionary around the time of the terror, 1793-94 (also, remember that the terror government declared 1792 the “year zero” in the Revolutionary Calendar–see the name of the theater established by Guillaume). Also, when they discuss “terror,” the specifically French historical connotation of the term is always present, I’d say much more strongly than a reference to 20th c. “terrorism.” (Though a few years later, such a cell would basically turn into the Baader-Meinhof gang).

In conjunction with this, the film is rife with references to the Romantic period (the Revolution itself being perhaps the main marker of that period). It’s not only the pervasive intertext with Goethe’s “Wilhelm Meister,” but also the presence of Novalis’s portrait on the wall (until it is taken down and used for target practice).

To this, the film (which is *very* French from this point of view, since this is, basically, the foundational dichotomy of French culture) the film juxtaposes the icons of French Classicism. Specifically, there are several shots of the portrait of Descartes. At the end, when Guillaume talks to the woman at the door of her apartment, he is quoting/misquoting a couple of lines from Racine’s “Iphigenie.”

Domingos, elsewhere on this blog, has discussed the red upholstery and lampshade in the shot of their dining room as standing in for communist “red.” However, if you look at the overall shot, there is red furniture, white wall, and a blue-painted door, the French tricolor! That this is the correct interpretation can be seen also in the trailer, where the title, “La Chinoise” is set in red, white and blue letters. Remember that the tricolor originated in the French revolution, and indeed Guillaume is also wearing it on his revolutionary costume.

Also–the translation in the subtitles is execrable, clearly written by someone not fluent in Marxist jargon, who therefore does not know to translate it idiomatically. If you listen to the dialogue, the lines come directly from Mao, etc.–for example, they correspond exactly, not “almost,” the the quote from “Where do correct ideas come from” that Craig quotes above.

Lastly, as Anne W. points out in her interview, the film is like a Marivaux comedy. It IS really funny, and that needs to be accounted more by the various responses I’ve seen (McCabe, on the DVD, doesn’t seem to get this at all.)

Anyway, these are just observations, that could be re-arranged, played against each other, to provide a more complete interpretation of the film–but I don’t have the time or energy to do that now.

I swear I hadn’t thought about Baader-Meinhof in ages and suddenly it’s coming up all over the place. I acquired a red car recently (after my husband got in a crash that totaled our previous car) and a facebook friend said it was Baader-Meinhof red. (We’re calling it Comrade Auto.)

Andrei, do you see tension between the tricolor and the maoist theme? OK, I don’t mean that question as academic as it sounds — I’m not trying to suggest ambiguity, that the “red” is both communist and French, but I think there’s a knee-jerk tendency among Americans especially, because of the way the Cold War was so stridently a them/us patriotic issue here, to feel that it’s somehow impossible to be both a communist and a patriot. Would French viewers of this film in ’67 have had a similar sense that this juxtaposition was challenging in some way, or even just politically charged — or would it have just been an easy extension of the clearly patriotic role the French communists played in the Resistance?

There’s a Baader-Meinhof film on Netflix Instant that I’ve been meaning to watch for a long time. Maybe now is the time.

Really, Derik? What is it?

I think this is definitely the time.

I keep debating the idea of getting a sticker with a red star and a machine gun for my back bumper. I’m leaning toward a red army sticker instead…I live too close to the NSA headquarters for the hardware. ;)

Maybe this? http://movies.netflix.com/WiMovie/The_Baader_Meinhof_Complex/70112501?trkid=2361637

That’s the one.

On the run–I don’t think the tricolor is meant at all to signify patriotism… Besides, remember, Godard is Swiss. The tension between the tricolor and the red flag was there ever since the Paris Commune.

Also–I meant to type above that 1792 was year one, not year zero. The reference still stands (though it could also be to Rossellini).

Caro, if I’m not mistaken, your new car isn’t just baader-Meinhof red, it’s a Baader Meinhof Wagon, isn’t it?

I figured Godard’s use of the red white and blue at the time was to suggest France, the US and imperialism.

Yes, Godard is Swiss but culturally speaking he is French. He doesn’t follow Swiss politics, for instance, even though he’s lived there for decades.

LOL, Andrei, it is indeed. Comrade Auto has a capitalist streak!

I think a better name would be Comrade Otto!

I always thought the ultimate Baader-Meinhof film was GERMANY IN AUTUMN, made by several directors (including Fassbinder and Schlondorff) to protest the Draconian reaction of the West German government to B-M terrorism…

The “year zero” reference does cite Rossellini, but it might also be another reference to Brecht. (After all, it’s Brecht’s name that gets erased last by Guillaume from the chalkboard…) Brecht makes numerous references to a “zero staging,” where the set is a blank canvas waiting for careful decisions to build up the mise-en-scene. I’m away from my files right now, but I remember lines like “Adding a chair is adding a lot” and such from Brecht’s notebooks–indicating, I think, that it’s a fine line between artistic staging and the creation of illusion and identification.

I’ve learned so much about LA CHINOISE from this thread–maybe we should all tackle the film a la the Harvard Group that did the shot-to-shot analysis of TWO OR THREE THINGS? (http://www.amazon.co.uk/Two-Three-Things-Know-About/dp/0674915003)

Andrei wrote:

“First of all, in response to Jim, it is clearly specified that Henri was beaten up by the “PCF.””

Looking at a transcript of English subtitles for the films suggests otherwise:

—————————

– He was beaten. – By whom?

– I’ll get some water. – By whom?

A commando.

Hurt? Was it fascists?

No, Communists.

Now, right away, where?

Permalink here (line 71)

The meeting on the Cultural Revolution.

The Sorbonne Marxist-Leninist group?

I told you they were disgusting.

—————————

The communists in question would seem to have been Maoists from a rival faction, not the PCF. If it was the PCF that attacked Henri, it’s doubtful that he would have been so eager to rejoin them after his expulsion from the Aden Arabie Cell.

What is the name of the Jaques Aumont book which is cited regarding Véronique’s contradictory reading of Pekin Information and the images of popular fashion behind?

It’s not a book–it’s an article by Aumont (translated by Jill Forbes) titled “This is Not a Textual Analysis (Godard’s LA CHINOISE).” The article was published in CAMERA OBSCURA 3-4 (Spring-Fall 1982), which is a big, fat special issue on Godard that is well worth a fan’s time. (It’s also includes that hilarious debate between Godard and Pauline Kael later reprinted in the book JEAN-LUC GODARD: INTERVIEWS.)

Ah that’s great- the page reference for the quote that is included in your essay about veronique and the fashion images behind her doesn’t seem to match, it says p91 on the quote but the journal article was between pp131-160. I want to use the quote in an essay but I don’t have access to the article. Would you be able to shed any light on which page number it came from?

“Also, Godard goes to great pains to show that the students are ignorant of Marxist theory and infatuated with the distinctly non-revolutionary attractions of popular culture.”

I think that is a bit of a mischaracterization. They generally come across as quite knowledgeable about Marxists texts, certainly more so that their counterparts in the US at that time. Throughout the film, they quote extensively from Marx, Lenin, Mao, Althusser, and other Marxists. It’s concerning the application of ideas drawn from these texts where they fall down. They cannot properly apply these ideas in their political praxis nor in their personal lives.