1963 was an eventful year for the Civil Rights Movement: MLK wrote the Letter from Birmingham Jail in April, in the city that erupted in riots a few weeks later following the integration of the University of Alabama. Medgar Evers’ murder occurred in June, the same month President Kennedy delivered a televised speech calling for civil rights reform. King delivered the I Have a Dream speech during the March on Washington in August. And in September, Birmingham erupted in riots again after the deaths of four young girls at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

It’s also the year the state of Maryland passed a bill prohibiting discrimination in public services. Living in Maryland in 2012, in the most affluent predominantly African-American county in the United States, it’s difficult to imagine that less than a decade before I was born, African-Americans in this very county, then much more homogeneously white, were unable to get a haircut at the downtown barbershop or eat at roadside restaurants.

Maryland’s bill wasn’t all that different from other similar ones – except for the involvement of the United States Office of Special Protocol Services, a division of the State Department charged with solving the problems faced by non-white diplomats as a result of systematic race discrimination in the US. The Office got involved in something that on the surface looked like an internal State of Maryland matter because foreign diplomats, particularly African diplomats, driving US Highway 40 between the United Nations in New York and their embassies in DC or the US Federal Government faced discrimination which violated their legitimate expectations as diplomats and generated terrible press in their home countries. By 1963, the State Department saw race discrimination as a threat to their global diplomatic agenda and a liability in positioning American-style democracy as the moral counterweight to Soviet communism.

The Soviets viewed it as an American weakness as well. State radio in the USSR devoted extensive propaganda output to the tumult of the Civil Rights movement. During the Birmingham riots, the USIA reported that the Soviets dedicated 1/5 of their total broadcast time to coverage of events in Alabama. They also continued to use race against the US in narrative propaganda; 1963 marked Soyuzmultfilm’s release of the animated Mister Twister, based on the much-loved poem by Samuel Marshak that tells the story of an American business man who is overwhelmed, angered, and eventually transformed by his experience in a racially integrated society during a visit to Leningrad.

Marshak was an exceptional translator of English-language literature and wrote children’s books in part because they allowed him to avoid the ideological demands and problematic realities of Soviet realpolitik in favor of less ambiguous moral terrain. For reasons I don’t know, Marshak was designated an Enemy of the State during his tenure as head of the Children’s Section of the State Publishing house; apocrypha has it that he escaped the purges only because Stalin himself was so fond of Mister Twister’s story. Doris Lessing wrote about Marshak’s dilemma in her autobiography:

The nicest result of the visit to the Soviet Union was that I became a friend of Samuel Marshak, one of the prominent Soviet writers, a winner of the Stalin Prize for Literature. He was a poet, translated Burns and Shakespeare, wrote children’s stories. At that time writers unable to write what they wanted, because of the persecutions of serious literature, chose to do translating work: this is why the standard of Russian translation was so high…I do not see how any writer could have a worse fate than Samuel Marshak’s. To be a peasant boy with genius – or even talent – at that time was to be seen as the inheritor of a glorious future. To be Gorky’s protégé was to be accepted by the most famous writer in Russia. Gorky steadily fought Lenin over the inhumanity of his policies, procuring the release of hundreds of political prisoners, and then he fought Stalin too: it would have been easy for Marshak to feel allied with the good side of the Revolution, because it was then still possible to think there was one. Slowly he was absorbed into the structure of oppression, but hardly knew it was happening. By the time he knew he was trapped, it was too late. Easy to say, for people who have never lived with the experience of political terror, ‘He should have opted out.” How? He would have been sent to die in the Gulag, like dozens of other writers. ‘I never wrote what I should have written,’ he said.

Although the film of Mister Twister was made in 1963, the poem was written thirty years earlier, in 1933. That same year, one of the earliest uses of moralistic anti-racist ideology in anti-imperialist propaganda, “Black and White”, gave an antebellum flavor to its documentation of Jim Crow racism. The film was directed by perhaps the most important Soviet animator, Ivan Ivanov-Vano, who collaborated with Shostakovich and Stravinsky and who taught at the Gerasimov Institute of Cinematography from 1939 until his death in 1987.

Ivanov-Vano’s film trafficks in the iconography of racism, the caricatures of Picaninny and Brute, and yet manages to convey great pathos, much more than is generally associated with caricatured representations. There is no comedy here; only the violence of those representations, removed from the historical context that created them and stripped bare of all ambivalence. For Western viewers today, the insistence of the representation’s moral starkness undermines their conventional signification and allows the aesthetic merits of the film to come to the foreground. For Soviet viewers in the 1930s, that moral starkness played directly into the hands of a good/evil propagandistic ideology that obscured as much as it revealed. Although the ending of Black and White is more didactically Communist than Mister Twister, that doubling suggests that the same tension between realpolitik and the morality of Marxist ideology likely informed the creation of this work. Perhaps it inspired Marshak’s poem.

Soviet propaganda targeting American racism was not limited to animation — there were live action movies such as the 1936 film The Circus, about an interracial couple fleeing prejudice, and a great deal of non-fiction and journalistic propaganda as well. The linking of racism with imperialism was immensely effective among non-white groups worldwide, particularly in African nations. At least as early as the Truman administration, US leaders saw policy positions in support of civil rights as a necessary component of efforts to contain the spread of communism. In 1962, the United States Information Agency hired the documentarian George Stevens, Jr. to head its motion picture operations. Stevens hired filmmakers such as Charles Guggenheim, Leo Seltzer and James Blue to create films for the USIA, intended to counterbalance the skilled and artistically powerful Soviet propaganda machine. In 1963-4, Blue directed a behind-the-scenes documentary about the March on Washington, capturing the groundswell of enthusiasm and conviction that animated the event.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jidABYf_nLU

The film, which was unavailable for viewing in the United States until 1990, unsurprisingly generated high-level controversy at the time of its release. Although intended to depict the Civil Rights movement as an exemplar of the positive functioning of democracy and the power of the first amendment rights to speech and assembly, diplomats within the USIA worried that it showed too much of the fomenting dissent and actually supported the Communists’ message. A number of Congresspeople objected to the romanticization of the protest (as well as to the depiction of interracial mixing). Eventually an introduction was added to make explicit the film’s message that peaceful assembly and the right to petition the government for redress are the mechanisms by which democracy expands freedom. Although emphasizing the message in some ways diminishes the impact resulting from James Blue’s more subtle presentation and makes the film more overtly propagandistic, there is another sense in which it adds a layer to the message: the director of the USIA, Carl Rowan, who presents the introduction, was one of the first African-American officers in the US Navy and was the very first African-American to serve on the National Security Council.

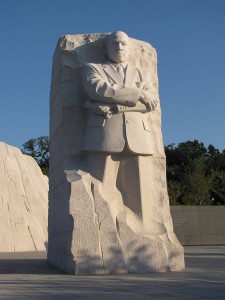

I have mixed feelings about the vaguely Socialist Realist aesthetic of the new Martin Luther King memorial downtown – colossal statues of famous men are broadly associated in my mind with oppressed people tearing those statues down. But I’m going to begin thinking of it as signifying the role that Cold War geopolitics played in bringing about at least one vitally important success of the Civil Rights era. In the same year that James Blue’s film was released to the world, the American Congress passed the Civil Rights Act. There were many people in the American government who supported that legislation because it was the right thing to do, but odds are there were others who supported it for pragmatic reasons of national interest. Thank God that the needs of our foreign policy aligned so well at that critical moment with the needs of our citizens at home.

Happy Belated Birthday, Dr King.

Democracy will not come

Today, this year

Nor ever

Through compromise and fear.

I have as much right

As the other fellow has

To stand

On my two feet

And own the land.

I tire so of hearing people say,

Let things take their course.

Tomorrow is another day.

I do not need my freedom when I’m dead.

I cannot live on tomorrow’s bread.

Freedom

Is a strong seed

Planted

In a great need.

I live here, too.

I want freedom

Just as you.

–Langston Hughes, “Democracy”

I think it’s maybe a little too cheery to think that geopoliticial concerns helped the civil rights movement? I’m sure they did to some extent…but on the other hand King was (and still is) smeared as a Communist, and of course, Soviet anti-racism just made many people blame the demonstrators for giving solace to the Communists.

Think about the opposite situation, though. What if people had seen Civil Rights as opposed to US interests abroad, rather than consistent with them? How much harder would that have made things politically?

I remain a little confused about the aesthetic choice for the monument, though, due to that smearing you mention.

The MLK memorial also struck me as being Soviet in style and impact. Instead of MLK speaking to a crowd, animated and passionate, we have him staring disapprovingly down at us. I think it a uniquely inappropriate monument to a man I can only see in my mind reaching out to people’s heart through words and actions. Oh well.

Great article. I don’t think it’s impossible to imagine that perceptions on the world stage affect internal issues. Tokyo’s push against manga originated with the disapproval of the American ambassador who complained that everywhere he looked he saw child porn. For many countries, how they are perceived globally carries immense weight.

Oh, I rather like the statue; rather than a warmly approachable Norman Rockwell MLK portrait, he looks like a pissed-off Dad telling us “kids” we better shape up:

http://www.papatodd.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/Chinese_MLK.jpg

http://www.prunejuicemedia.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/08/MLK-Memorial-Statue-1.jpg

On another vein… http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/hendrikhertzberg/2012/01/king-day-i-quote-unquote.html

http://www.newsytype.com/10452-mlk-memorial-statue-white/

“What if people had seen Civil Rights as opposed to US interests abroad, rather than consistent with them?”

Lots of people did. You don’t have to imagine the result. It sucked.

The point is, I think, that interests abroad helped with some groups and hurt with others. I think it’s often seen as a negative (those communist smears) so it’s definitely worthwhile pointing out that it had helpful aspects as well. And maybe it was even overall positive; hard to tell without being an expert in the period. But it definitely wasn’t all good.

It’s also worth mentioning that probably a lot of people in the Soviet Union, and even in the hierarchy, probably really did see U.S. race relations as evil, not just as a propaganda opportunity. Obviously Soviet leaders were not saints by any stretch of the imagination, but Khruschev at least has a pretty good claim to being more morally honorable than any post-war American president, up to and including our current leader.

In any case, it’s always easier to be morally outraged by someone else’s failings…which isn’t to say the outrage isn’t real. Just human.

I’m actually reading a bunch of stalin-era memoirs for my day job at the moment. Talk about depressing….

While I haven’t seen any published papers on the matter, the view I’ve most commonly encountered in the international relations field is that the Soviet Union was successful in shaming the U.S. on the topic. It comes up fairly often in discussion of soft power.

I suspect the mechanism would be elite opinion. There was likely a fair number of people in the U.S. foreign policy apparatus that were sympathetic to the civil rights movement but not especially involved. Soviet propaganda and public diplomacy efforts made the issue their problem as well.

Also, thanks for the research on USIA. My mother had worked their and generally speaking I’m always happy to learn more about their activities.

Sorry; procrastinating going back to those memoirs.

James Loewen (whose book I reviewed yesterday) in his book Lies Across America has an amazing essay about the Shaw Monument in Boston to the black civil war regiment. He talks about how the Shaw family demanded that it not be just Shaw, but include the black soldiers, while donors wanted Shaw prominently displayed. So they compromised.

Loewen quotes Mrs. Shaw telling the architect, Saint-Gaudens, “You have immortalized my native city; you have immortalized my dear son; you have immortalized yourself.”

I’ve read that essay a bunch of times over the years. It always makes me cry.

My take on the statue is that it fits in with our general pattern of secular deification. Probably not what MLK had in mind, but in DC given the overwhelming presense of memorials to wars, generals, and great white presidents, the MLK Memorial is a much needed deviation from the norm.

Also worth noting: concerns about how racism was perceived abroad wasn’t just a Democratic thing. Eisenhower intervened at Little Rock at least in part because he was concerned with Third World perceptions of the US.

In the photograph, at least, they’ve somehow made King look like Lenin. Seems problematic from any number of angles…

I’m waiting for the Malcolm X statue, myself. Wait…I found it. Wasn’t worth the wait.

http://www.soulofamerica.com/new-york-city-malcolm-x.phtml

The hypocricies that those Soviet animators addresses was also shared by low-budget American auteur Samuel Fuller.

In THE STEEL HELMET, one of (if not THE) first film about the Korean War, Fuller stages a conversation between a wounded Communist North Korean and Thompson, an African-American US medic who treats him. Here’s part of the conversation, from imdb.com (I couldn’t find the clip on Youtube):

The Red: “I just don’t understand you. You can’t eat with them unless there’s a war. Even then, it’s difficult. Isn’t that so?”

Cpl. Thompson: “That’s right.”

The Red: “You pay for a ticket, but you even have to sit in the back of a public bus. Isn’t that so?”

Cpl. Thompson: “That’s right. A hundred years ago, I couldn’t even ride a bus. At least now I can sit in the back. Maybe in fifty years, sit in the middle. Someday even up front. There’s some things you just can’t rush.”

Despite some seeming absurdities (did they even have buses in 1851?) and Thompson’s willingness to wait at least a half-century for desegregation, Fuller nails the same sense of hypocritical disconnect between the US’s emphasis on freedom and its actual discriminatory practices. (And Fuller would continue to discuss race in provocative ways, maybe most notably in WHITE DOG, where Kristy McNichol [!] and Paul Winfield try to reprogram a dog trained to attack Black people.)

Caro, is that Paul Robeson singing in the animated video? Do you know?

Noah–have you read Robert Lowell’s “To the Union Dead”? The poem, I mean, not the entire book. You should.

Yep. Loewen quotes it in his essay as well.

I’m not a big fan of Lowell’s in general. I like the “savage servility” though….

It is Paul Robeson, Noah. What I wasn’t able to find out, though, is whether it was the original music that Ivanov-Vano intended for the film or whether it was added in later. I think there was a recording made in the early 1930s, so it’s possible, but completely unsupported.

Greg, thanks for commenting; nice to see you on here! Connecting it to soft power makes sense; there’s no way these films weren’t at least a volley in the ideological Cold War, and I agree they would have had at least some influence on foreign policy elites. Also, the effects of the Soviet propaganda were really effective and tangible in Africa; I didn’t get into that here but human rights for African-Americans was a major topic at the 1963 Conference of African Heads of States and Governments, at which the Organization for African Unity was established. That conference occurred in May, the same month as the violence in Birmingham. The events in Alabama nearly triggered an international incident: the President of Uganda released an open letter to President Kennedy on the second day of the conference protesting the events, and the conference contemplate a censure and a break in diplomatic relations with the US. Only the refusal of the President of the Congo to sign onto the censure averted the incident — the Conference ended up producing a protest resolution instead that did recognize the efforts to end segregation and the power of peaceful protest. On his subsequent visit to the US, President Haile Selassie compared the movement for African Unification to the Civil Rights movement.

To understand the significance of this within the diplomatic community, Noah, remember this is a time when the various forms of black nationalism were serious alternatives for the nascent black power movements. It mattered to Kennedy’s administration that the African nations not align with African-Americans in a movement against US sovereignty that could have escalated the civil rights movement into a civil war. I think people often underestimate how extraordinary vital Dr King’s leadership was in making sure that Civil Rights did not go in that direction. But in 1963, these were not even close to minor issues. They would have been strong motivations for our diplomatic corps.

Erica, I didn’t know the American ambassador triggered the anti-manga push. Soft power indeed, eh?

Craig, I’ll have to check out that Samuel Fuller movie. It doesn’t surprise me that the same themes the Soviets were using showed up in American art as well. I’m guessing this has something to do with why Fuller was harassed by HUAC? One of the things I wanted to find out but couldn’t was whether the US also made animated propaganda on this topic — all I could find was the documentary material.

Richard, I didn’t intentionally exclude Eisenhower…I just had more information on Truman and Kennedy! But definitely an important point that this was not partisan.

Mike, thanks for the links!

My Robeson disc includes material from the late 1920s, so he definitely had recordings from back then. And he was a Communist himself, of course.

I didn’t know about the African diplomatic protests. I still don’t think this is right though:

“It mattered to Kennedy’s administration that the African nations not align with African-Americans in a movement against US sovereignty that could have escalated the civil rights movement into a civil war.”

The only place where there was ever going to be an effective civil war of liberation of blacks against whites was in the (understandable) fantasies of some black nationalists and the (vile) fantasies of some racists. The power disparities were simply too great. Kennedy, Eisenhower, etc. saw racial unrest as a diplomatic embarrassment, but I’ve never seen anything to suggest that anybody with access to the nuclear button thought that black rebellion, supported from abroad or no, was going to lead to a second civil war.

—————————

Craig Fischer says:

…Cpl. Thompson: “That’s right. A hundred years ago, I couldn’t even ride a bus. At least now I can sit in the back. Maybe in fifty years, sit in the middle. Someday even up front. There’s some things you just can’t rush.”

Despite some seeming absurdities (did they even have buses in 1851?)…

—————————-

Yes, just horse-drawn buses:

A “Reconstruction of Shillibeer horse bus of 1829,” from England: http://www.ltmcollection.org/images/webmax/kc/i00006kc.jpg

http://www.buspictures.net/bus-history.html shows another horse-drawn bus; then mentions (with a photo) how “From the 1830s…steam powered buses came into being…”

——————————

Caro says:

Mike, thanks for the links!

——————————

You’re welcome! I do love to “link”…

There’s a large body of literature in history and political science that addresses in detail the complex relationship between civil rights and the Cold War. The NAACP has come under considerable criticism for caving to the anti-communist witch hunts and ditching what had been an international agenda that aligned with precisely the sort of liberation movements Caro mentions. A google scholar search will throw up at least a few articles and books, and there are many more.

I just read Stokeley Carmichael’s “Black Power” recently; he was quite explicit about wanting to link African-American and African liberation movements.

Noah, I don’t think there was ever any concern about a protracted civil war like the one in the 19th century, but Malcolm X was calling for the establishment of separate black institutions, independent black government and safe havens on American soil. At the time of the African convention, Birmingham was on fire, white on black violence was not only escalating but showing up on tv, and I think it was imminently reasonable for leaders to fear the possibility of having to use violence to put down a serious armed resistance, possibly multiple times in multiple locations — and even more reasonable for them to not want that armed resistance to involve an international force. That they would have thought about how awful that would be and prepared to make it not happen doesn’t seen odd to me at all. It’s honestly more surprising that African-Americans kept their faith in the American nation and went with peaceful protest rather than violent conflict. I think about the lynchings and the prejudice they faced and it seems like an impressive choice to me.

I dunno Caro…you think African nations were seriously going to ship arms to black rebels on American soil in some sort of significant way? That seems pretty staggeringly unlikely to me.

And, indeed, the Black Muslim’s program of independent enclaves on American soil was always staggeringly unlikely. James Baldwin talks about it in the Fire Next Time; he basically says he can see the appeal, but that from any practical perspective it was clearly not going to happen. The brutal suppression of folks like the Black Panthers suggests that the U.S. was always quite able to deal with that sort of threat…and, indeed, use it as a way to ideologically consolidate state power. Where do you think the impetus for our current insane prison system comes from?

The thing about King is that in a lot of ways he wasn’t a dreamer. He was much more of a realist than Malcolm X or Stokely Carmichael. Peaceful protest was the effective option open to African Americans. Civil war and armed insurrection and independent statehood — those were never going to happen. King was a brilliant strategist, among his many other accomplishments.

I certainly agree that peaceful protest was an impressive choice — but it was an impressive choice in part because it was the smartest choice available. To see that took a lot of insight and courage, I think.

None of which is to denigrate the black power movement. “Black Power” the book is actually startlingly clear eyed, and the strengthening of independent institutions and self-defense are obviously worthwhile goals in a lot of contexts. And I’m sure you’re right that foreign condemnation affected the U.S. It still seems like a leap to think that the U.S. actually felt threatened by foreign condemnation in some sort of military way, rather than simply tactically embarrassed. (Which is important in itself.)

I don’t think the US felt threatened militarily. The US almost never feels actually threatened militarily.

However, they did fear the geopolitical consequences of violence over civil rights, especially the increased African involvement that violence would have led to. Even having the African dictators issue a formal statement of ideological support for separatism (as opposed to political change) would have been a pretty destabilizing international incident. They were already considering withdrawing their ambassadors: A “break in relations with the US” was seriously discussed at the Conference and was the original language of the statement on Birmingham that the Conference issued. The President of the Congo basically threw his weight around, got the language softened and gave the US time to pass the Civil Rights Act. But the states certainly kept their rights to break with Washington if things didn’t get better, and they likely would have maintained diplomatic contact with the separatist groups — the Nation of Islam had its own “ambassador” in Cairo. The African states were very emotionally invested in the situation facing African-Americans, and had the US not taken really decisive action quickly I think their involvement absolutely would have increased. Would they have sent arms? Probably not. Would they have sent MONEY? Probably so. Possibly even Soviet money.

Remember that one of the major military goals of the Cold War — because it was a Cold War — was preventing nation states from aligning with the Soviet Union. Had a large number of African countries broken off relations with the US, I think we would have considered that a strategic military problem, not just a tactical embarrassment.

So yes, absolutely, the US military could have completely suppressed anything the black separatists did, with African support or on their own, with almost no effort. There was no real threat at any point, even in theory, to stability or sovereignty from the black separatists. That’s not the point.

The point is that the US could not afford to be in the position of routinely engaging in violent clashes with a widespread and organized separatist movement that was exposing holes in our committment to our ideological position AT ALL. We couldn’t afford to show up on global news reports killing people because they’d decided America wasn’t ever going to allow them to enjoy the freedom that we claimed we wanted for the whole world. That would have absolutely cost us the propaganda war.

The US military routinely taking violent action against separatists (which amounts to a civil guerilla war) would have been geopolitically destabilizing. The Africans, drawing on the experiences of their diplomats and faced with images of children dying in the South, would have supported the separatists — as would the Soviets. Even our strong allies would have objected very strongly.The government would have won any conflict it went into – but at what cost?

So the diplomatic corps took the possibility of sustained violence — even guerrilla violence — very seriously because the fallout of it would have affected our operations worldwide. It would have been a colossal failure to let things get to that point. We were trying to win and maintain global position via a propaganda war that for an awful lot of government elites was more important than civil rights. I think that context had a lot to do with the way things played out. I think it was an important factor to why the Civil Rights Act passed when it did — and the situation was a lot difference once that was passed, because after the government took that position formally, civil rights violence became sectarian rather than revolutionary, and its geopolitical shadow changed dramatically.

I agree with all of that…except for the suggestion that the issue was sustained violence. A propaganda defeat didn’t have to involve violence. The continuation of peaceful protests were probably even more damaging in terms of public opinion, right? If they’re not actually scared of violence as a destabilizing force in itself (which I can’t imagine they were) then you don’t need to look to black nationalism to explain why they were worried about negative public reaction. The Civil Rights movement in itself was an embarrassment. And the response from African nations was dangerous for geopolitical reasons regardless of whether there was a threat of aid to an insurgency in the U.S. — which I still think is an extremely improbable scenario.

It’s a soft power issue. The threat — even as you say, the military threat — was that public opinion would turn against the U.S. in a decided way. But that could happen, and was happening, without the threat of an insurrection (though, of course, there certainly was a certain amount of violence (Carmichael calls it rebellion) — after King’s murder especially.)

Maybe we’re talking past each other…although I don’t think the continuation of peaceful protests is as damaging as the government having to roll out artillery to quell a violent separatist movement — especially when the separatist movement has the moral high ground. Any violence from the government against the activists would have been much worse than either protests or sectarian violence.

But I don’t think you HAVE to look to black nationalism for the explanation; I just think it was PART of the explanation, one thing, among many, that they were worried about.

Also it wasn’t just public opinion: an awful lot of cold war politics is the maneuvering of geopolitical alliance, and violence is more likely to actually affect the opinions and actions of foreign governments than peaceful political protest.

That’s why I think the Civil Rights Act was so important — it got the US government officially and legally on the right side of the conflict, making the subsequent violence sectarian rather than revolutionary. It’s a lot easier for propagandists to spin political demonstrations in that context than it would have been to spin the suppression of a separatist movement.

One thing to consider is that throughout the Cold War, and particularly after the Soviets tested their bomb, creating an appearance of national unity was a major priority. The Civil Defense effort was, in many respects, a national performance orchestrated by the federal government by way the states and local governments. The idea was to create a display of solidarity that would make us look less likely to crumble after an attack. Race played a role in this inasmuch as disharmony that couldn’t be pinned to communist infiltrators had to be smoothed over. It was a tricky balance, and led to the sorts of weird half measures and loose alliances between presidents and civil rights leaders at the time.

This is all a long way of saying that what was often important was preempting the appearance (from the outside looking in) that revolution was plausible, regardless of what the politicians on the inside thought was the case.

PS:

Throughout the Cold War is wrong. I should have written that creating the appearance of national unity was a high priority during the civil defense era, and maybe up to detente. I need a second cup of coffee.

This is a totally great article and thread.

I need to read more carefully, Caro, but was there actually a suggestion that violent separatism would have been preferable because it would have meant messier public relations for the government? I mean, as Blame America First as I am, suppressing internal post-colonial populations violently has some disapprobation– like Kosovo or South Africa, but those aren’t really cases of well-organized uprisings– but it seems like countries with power are left to let blood run in their own streets as they see fit, as long as they have nukes and/or don’t have oil or anything else we need.

But, in the spirit of Cold War propaganda embarrassment, have you all seen the stuff about the CIA using Abstract Expressionist art to promote American interests abroad?

Do you have a link on the AbEx? That’s pretty funny. “America! We will spatter your blood across the continents, then unleash genius artists to repurpose the stains for your aesthetic pleasure!”

This is a good article about it: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/modern-art-was-cia-weapon-1578808.html

The situation is actually a lot more complicated than it might appear, and given the repression of modern art as decadent in the USSR (which directly echoed the Nazis’ notion of “degenerate art”), the message conveyed wasn’t exactly wrong.

Here’s a great Soviet cartoon extolling the virtues of traditional over modern….

Glad you liked the essay, Bert! The point I was trying to make about violent separatism was just that diplomatic circles were really anxious about the escalation of the Civil Rights conflict — they could spin the peaceful protests, but they really wanted to government to get on the right side of the conflict, for our policy to be consistent with our stated values, before things got any more unstable. Does that answer your question? I brought it up as an intensifier to the broader point I make in the article. Noah objected to this sentence in my comment above: “It mattered to Kennedy’s administration that the African nations not align with African-Americans in a movement against US sovereignty that could have escalated the civil rights movement into a civil war.” I gather, Noah, it was just because the phrase “civil war” was too extreme for what would have been basically guerrilla skirmishes? I just tend to think anytime there are violent separatist clases that’s a type of “civil war”, but I can see how in the context of American race relations it connotes a much more structured conflict…

“the message conveyed wasn’t exactly wrong.”

It’s hard to be entirely wrong with anti-Stalinist propaganda.

The awesome Khruschev biography by William Taubman has some amazing passages talking about Khruschev and the arts. A lot of artists wanted to embrace him because of his anti-Stalinism, but he was a thorough philistine (not unlike Joe McCarthy.) He’d go to these exhibitions, and the artists would gather around, and he’d just rant at them for hours. He said to one artist something like, “It is like I have crawled into a toilet, and I look up, and someone is sitting down and does their business. That’s what your art is like!”

Which is almost a poem in itself, really.