Franklin’s blog on Friday alerted me to this post by Nathan Schreiber. Schreiber’s point — about the art world being dominated by elites while the book world isn’t (as much) — ties into the conversation Franklin and I were having on Thursday.

But what really struck me about Schreiber’s post is that it was just really nice to hear someone in comics say something really positive and affectionate about fiction, because it just doesn’t happen all that often. Franklin quotes a Facebook post from Schreiber:

My post was really an expression of frustration with comics trying to climb further into the art world. Because I think comics are “stories” and while stories can be art, I think they’re stories first and art second. The art world is full of ambiguities, dominated by concepts over content, and is controlled by elites where the world of stories, well, it just makes more sense. There’s more or less universal recognition of what a good character is, a tight plot, hell, even mood.

Although he’s not necessarily talking about literary fiction (and I haven’t seen this Dash Shaw to know whether I agree with his evaluation), this comment vaguely acknowledges something extremely important that comics (and probably fine art too) should listen to: great fiction writers retain their craft even as they layer in more and more conceptual complexity. Nabokov, Pynchon, Delany, Woolf, Swift, Chaucer — there’s no shortage of concept, but there’s also plenty of craft. The craft enables the concept: the more solid the prose is, the more concept can be layered in. And sometimes the concept also illuminates the craft.

There are worthwhile exceptions, usually experimental ones — nobody’s ever going to claim that Burrough’s The Soft Machine is even a remotely good example of the writerly craft, but it’s an overt experiment, a conscious effort to figure out how to do something new and challenging. But he — and writers like Pynchon who followed him — made a successful effort afterwards to reintegrate craft with the formal and conceptual lessons learned from the experiment.

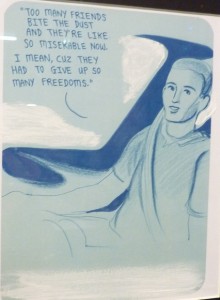

(It’s possible the caption under this Dash Shaw image in the Schreiber post is sarcastic, but it also doesn’t seem that far-fetched to claim an interest in concept for Shaw.)

There are some really brilliant avant-garde cartoonists who are on really exiting trajectories toward merging experiment and craft, like Jason Overby and Warren Craghead, and I’d like to see more cartoonists follow their lead and incorporate their insights and build on them to make new insights and eventually get to the point that cartoonists are making graphic fiction that’s as strong conceptually as literary fiction.

To do that, though, people have to get past this knee-jerk notion that craft and concept are an either/or choice. A lot of indie/alt cartooning has turned punk and underground ways of seeing the world into a fetish for harsh, angry expression and just plain ugliness, as though ugliness itself is sufficient to make a work edgy — as if ugliness is somehow inherently more meaningful than beauty. Like scatology and mundaneity, ugliness in indie comics is often a shortcut, a way of giving the illusion that something significant is going on when it really isn’t. Comics critics have mostly embraced this extremely facile way of thinking about concept as mere symbolism. In the alt comics subculture at least, I do think some of it comes from the mild contempt for writing that so many people seem to think is necessary in order to appreciate art. Maybe more of it comes from the fine art world as Franklin so often suggests. I’m willing to consider the assertion that in truly non-narrative work, an allusive, symbolic, suggestive use of concept can be successful, but I stick to the opinion that in narrative work, concept needs to be crafted so that it works with the narrative in interesting ways.

Ugly or otherwise, though, a lot of the work — in fine art or comics — that claims to be so “high concept” doesn’t really strike me as actually being all that high concept. It’s more “heavy concept” than “high concept.” Blunt, poorly wrought, overdetermined concepts weigh art down; elegant ones elevate it. I don’t think there’s a forced choice between beauty and concept; there is an aesthetic aspect to the conceptual constructs of an artwork as well (Pale Fire, which really is high-concept, is a great example, as is, say, Grünewald’s Crucifixion). But the artist just has to be willing to spend a lot more conceptual energy than most cartoonists — most artists period — are willing to do.

Postscript (added 1pm ET)

I want to be sure it’s clear that of course there’s a good bit of subjectivity involved in saying that this one thing is ugly and some other thing is not. There’s not an absolute standard. I find Ariel Schrag’s work a little aesthetically harsh, for example; Noah finds it really beautiful.

So I don’t want that pithy encapsulation up there about ugliness as a shortcut to be interpreted as a critique of any particular specific comic. It didn’t arise out of a specific reading — more an overall experience of seeing too much scatology, too much ugliness, too much mundaneity and not enough richness, not enough concen with beauty. Not from any specific cartoonist in any specific instance, but in the aggregate. The collective drive for and commitment to those aesthetics overall within indie comics often seems to be standing in the place of a drive for and commitment to more meaningful conceptual engagement.

In general, it raises the question of whether ugliness and rawness can simply be substituted for beauty and craft without any loss to the artform overall. Can you operate from a belief that ugliness is beautiful without transforming where you end up, collectively, at the end? I don’t really think you can — I think ugliness and rawness have semiotic content; I think they signify in a different way from beauty and craft. And I think their potential as such to hold a richness of meaning is more limited. But I also think — and this is the point of the post — that questions of how ugliness and beauty become meaningful, and what kinds of meaning they make, and what work is necessary to connect form and concept are discussions worth having.

In film, doesn’t “high concept” just mean something simple enough to make sound good in a pitch?

Isn’t it most-often applied to Spielberg and post-70s mainstream cinema? Could you clarify how that’s distinct from your idea of the bluntness of “heavy concept” (other than the counter-intuitive idea that the gallery arts have the same problems as Hollywood)? Or does “high concept” just mean different things in literature and fine art circles?

I think literature eschews the idea of “high concept” with some pretty vigorous scoffing.

But there also this. And the truth of the matter is that most really elegant conceptual work in literature actually can be summed up that way. If the concept congeals, you can get it into that “pitch” format. If the concept doesn’t congeal, it’s going to lie there like a dead weight — whether it’s a simple concept that will grab a wide demographic or an ambitious one targeting a narrower one. (This is sort of related, it occurs to me, to the conversation I talk about with Darryl Ayo in my post on SPX.)

I mean, you could rephrase what I’m saying into “heavy concept = lousy or failed high-concept”, I suppose. But the issue is really why does it fail — odds are most successful high-concept pitches at some point were having some trouble with their own weight, but someone somewhere did the work to give them air.

Gregor Samsa waking up one morning as a giant insect is definitively high concept… but obviously it works not only because of the concept, but because of the craft and details…

“Like scatology and mundaneity, ugliness in indie comics is often a shortcut, a way of giving the illusion that something significant is going on when it really isn’t. ”

Preach it.

It’s interesting to me that Schreiber’s post didn’t get more comments. I’d have thought people would be opinionated about it.

I also couldn’t quite tell whether he was actually claiming that the Dash Shaw books are ugly, or whether it was just an example he was using to distract attention from the actual unnamed ugly book.

All – note that I added a postscript. When I got to thinking about how unclear I was regarding Schreiber’s opinion about the Shaw, I wanted to be clearer myself that I wasn’t judging any particular comic when I wrote this. These are general thoughts about a theoretical concept, not criticism of a specific work.

To do that, though, people have to get past this knee-jerk notion that craft and concept are an either/or choice. A lot of indie/alt cartooning has turned punk and underground ways of seeing the world into a fetish for harsh, angry expression and just plain ugliness, as though ugliness itself is sufficient to make a work edgy — as if ugliness is somehow inherently more meaningful than beauty. Like scatology and mundaneity, ugliness in indie comics is often a shortcut, a way of giving the illusion that something significant is going on when it really isn’t.

Well, I blame The Comics Journal.

While Groth and company always deserve credit for bringing a semblance of real-world critical standards and dialogue to the field, things have long been past the point where the values they promote have become a pernicious influence. In general, the magazine’s contributors have always implicitly evaluated new work through the prism of the Surrealist aesthetic as popularized by the Beats. The highest goal of art in this view is “self-expression.” Anyone who disputes this should consider why the magazine is all but defined by its idolatry of Crumb and his counterculture peers. Those are the artists who brought that aesthetic to comics. The magazine has always championed Surrealist/Beat modes such as confessional stories and dream narratives over every other approach. The accompanying fetishization of grittiness is why harshness and ugliness are seen as values. The lack of varnish is taken as a signifier of authenticity, and as such, the work is “purer” self-expression and therefore better as art.

Because “self-expression” is seen as the highest goal, things like literary craftsmanship and erudition are treated with suspicion if not outright hostility. That stuff is seen as “artifice” and “pretentiousness,” which in this view are qualities that corrupt art. Skillful drawing is still valued–Crumb’s influence has its good side–but I believe that’s because it’s seen as necessary in the “authenticity” pursuit.

It’s too bad that it isn’t generally recognized that with, say, Harvey Pekar, erudition enhanced the quality of his observations and the judgment used in presenting them.

However, reading is hard work, and adapting the thinking of the better prose writers is even more difficult. Maybe these artists already feel they have too much on their plate.

Robert, I think there’s something to that…though it’s worth pointing out that tcj has never been monolithic. There are always dissenting voices, and I don’t think even Gary himself is perfectly consistent on this sort of thing.

I tend to think it’s not precisely TCJ that’s the source of the tendencies you’re talking about so much as the historical dominance of super-hero genre work. The undergrounds, TCJ, and to some extent the alternative comics movement were all reacting against that, trying to find ways to signal their antipathy to/distance from corporate crap.

Well, I did say “in general” and “implicitly.” I agree that TCJ isn’t a monolithic entity. I don’t think Gary would have been able to get the pages filled on anything close to a regular basis if it had been. But it has certainly fostered the aesthetic values that I outline above.

As far as the undergrounds, TCJ, and the alternative comics movement being a reaction against the dominance of corporate superhero comics, that’s a myth. They all grew out of other entrepreneurial trends. The undergrounds were a development from the college humor magazines of the 1960s. TCJ came out of the fanzines. Gary was a superhero-comics fan who’d been putting them out for years before starting TCJ. The alternative comics came about because there was a distribution and retail model that was able to support small-press efforts. And just about all the major first-wave alternative cartoonists started out as corporate-comics wannabes.

But in the process they also signaled their distance away from traditional illustration, which was often insistently beautiful. And I think that was intentional as well, because “illustration isn’t comics.”

I don’t think it’s a myth. Certainly, the fact that many, many folks in the undergrounds and in the alternative comics movement have affection and investment in superhero comics isn’t a refutation. It’s a confimration, if anything. There’s a love/hate relationship there, well epitomized by TCJ, which was both a fanzine itself and defined by its opposition to being a fanzine in a lot of ways.

Caro, I think there’s something to the idea that the undergrounds, etc., were distancing themselves from slick pulp illustration. It’s honestly hard for me to figure out what comics relationship to things like Ellen Rankin and Bob Binks is though. There doesn’t seem to be much dialogue there, whether embracing or rejecting. Maybe I’ve missed it though?

If you missed it I missed it too. Pulp illustration yes, with that distancing, but design “illustration” just doesn’t seem to be part of the conversation at all.

Of course, commercial comics weren’t all that hip to commercial design modernism either, like Binks and Raskin but also Lustig or Paul Rand, were they? So maybe alt comics inherited it, but just weren’t all that conscious of the inheritance.

Noah–

The underground cartoonists were humor people. The inspirations for ZAP were college humor magazines put out by Jaxon and Frank Stack. Shelton did them as well when he was at UT-Austin. Crumb didn’t have a problem with corporate publishers back then. He wouldn’t have licensed the Fritz the Cat material to Random House or his other ’60s work to Penguin if he did. The underground comics came out of the same publishing movement as the National Lampoon. I don’t know that Crumb and the others were ever especially aware of Marvel and DC’s output in those days. I’ve read nothing that indicates they saw themselves in opposition to those companies.

TCJ’s situation is complicated. I’ll just say that Gary’s hostility toward the corporate companies is far more rooted in his emotional make-up than in any principle. Actually, I don’t think Gary has principles. It’s just egocentric behavior dressed up in sanctimony.

With the major first-wave alternative cartoonists–the Hernandezes, Sim, Bagge, Brown, Clowes–they were all training themselves to work for the corporate publishers up to the point they undertook the work they became known for. I’m not just talking about Marvel and DC here; this includes Heavy Metal, Warren, and MAD. More than a few of their contemporaries, such as Bill Messner-Loebs, Jim Valentino, and Ty Templeton, did end up making the leap.

Robert, I’ll defer to your greater knowledge…but Crumb’s cover layouts, for example, just always seem to be riffing off mainstream comic tropes to me. Maybe he’s getting them from non Marvel and DC sources? Archie? Disney?

Caro, I don’t even know who Lustig or Paul Rand are! But yeah, commercial comics don’t seem plugged into commercial design modernism at all. I’m not either, except to have noticed that people like Binks and Raskin are awesome when they’re placed in front of my nose. Again, I don’t really know why there shouldn’t be a back and forth there. There does seem a little in Edie Fake or Lilli Carré? Or Kim Deitch maybe?

It could be part of comics trying to move away from children’s illustration? I think children’s illustration has much more of a link to that tradition; Binks and Rankin both are children’s illustrators, for example, among their other accomplishments. It’s a shame though; it seems like such a great tradition, and comics could certainly benefit from it.

Crumb was certainly inspired by the Disney stuff. He’s also a big fan of a superhero-comics cover artist named L. B. Cole. Maybe that’s what you’re picking up on.

Alvin Lustig was brilliant: http://www.alvinlustig.com/bp_intro.php

You know Paul Rand; you just don’t know you know Paul Rand. He designed these.

I imagine there’s indeed at least some influence of design modernism on Kim Deitch; his father’s work at UPA was pretty important to that aesthetic. (And this is my favorite thing Fantagraphics has ever put out. Modernist design was as much about advertising as it was about children’s illustration though, (although there is a great deal of overlap) so I’m guessing it’s also the counterculture’s suspicion of corporate culture…

Fascinating commentary, Caro!

————————

Caro says:

A lot of indie/alt cartooning has turned punk and underground ways of seeing the world into a fetish for harsh, angry expression and just plain ugliness, as though ugliness itself is sufficient to make a work edgy — as if ugliness is somehow inherently more meaningful than beauty. Like scatology and mundaneity, ugliness in indie comics is often a shortcut, a way of giving the illusion that something significant is going on when it really isn’t.

————————

Yes; not to mention, the Punk and Underground had specific motivations behind their ugliness. The harsh look of Punk — safety pins through the cheeks, hair roughly chopped, dyed unnatural colors — was the outwardly manifested equivalent of self-mutilation, in effect screaming to society at large, Mom and Dad, “look what you did to me!”

And the Underground — if we’re talking comics here — arose largely as a protest to the Vietnam War, the society shoving its youth into that meat-grinder, covering up its horrors with talk of “collateral damage, body counts, winning hearts and minds” and how “we had to destroy the village in order to save it.”

The example of Irving Penn, a hugely successful fashion photographer who only was taken seriously as an Artiste when he came out with a series of prints of battered, moldy cigarette butts is telling…

————————

“Despite working at Vogue magazine since 1943, Penn did not have an exhibition at MoMA until the mid-Seventies show of the cigarette butt series that, to me at least, must be seen in their monumental original size to be fully appreciated…

John Szarkowski in his wall essay acknowledged in passing Penn’s commercial work in the world of ‘haute couture or cuisine’ and said, with what appeared to be almost an apologetic sense of embarrassed dismissal, that ‘one might guess that he [Penn] has only rarely enjoyed more than a cursory interest in the nominal subject of his [fashion] pictures.’

“At the same time, it is hard to escape the sense that Penn was not being sardonic himself about this issue of his primary home being located in the ghetto of commercial photography. He had to be smiling to himself and at himself that, after three decades at the top of the profession, cigarette butts became his key to the pantheon…”

————————

http://theonlinephotographer.typepad.com/the_online_photographer/2009/10/irving-penn-fashion-photographer.html

S’more butts: http://nicholasspyer.com/2010/09/30/the-fashion-of-cigarette-butts-irving-penn/

————————

Caro says:

I find Ariel Schrag’s work a little aesthetically harsh, for example; Noah finds it really beautiful.

————————-

I wonder if you two are disagreeing that much, though. Without searching out Noah’s writing on the subject, could it be he finds her renderings “beautiful” as a child’s drawing or naive art can be beautiful, emotionally expressive in a direct fashion, even if lacking in polish, anatomical correctness, graceful lines? (Those “weaknesses” actually most appropriate for the subject; why, one of Schrag’s books was even called Awkward!)

Schrag’s work is outstanding, deserving of whatever praise it’s gotten. It’s actually a far more complex work, psychologically “deeper,” than the rightly acclaimed Fun Home.

Surely the far greater critical and commercial success of Bechdel’s book is due to its being more tidily structured; wearing literary depth on its sleeve, as it were; and rendered in a classically finished fashion.

————————-

Robert Stanley Martin says:

…Well, I blame The Comics Journal.

While Groth and company always deserve credit for bringing a semblance of real-world critical standards and dialogue to the field, things have long been past the point where the values they promote have become a pernicious influence. In general, the magazine’s contributors have always implicitly evaluated new work through the prism of the Surrealist aesthetic as popularized by the Beats. The highest goal of art in this view is “self-expression.” Anyone who disputes this should consider why the magazine is all but defined by its idolatry of Crumb and his counterculture peers. Those are the artists who brought that aesthetic to comics. The magazine has always championed Surrealist/Beat modes such as confessional stories and dream narratives over every other approach.

—————————

(???) Certainly, the prevalent “default setting” of most TCJ criticism was a rejection of commercialism and superheroes; but there was huge praised bestowed upon EC, the “Old Masters” of the art form given reverential coverage.

—————————

The accompanying fetishization of grittiness is why harshness and ugliness are seen as values. The lack of varnish is taken as a signifier of authenticity, and as such, the work is “purer” self-expression and therefore better as art.

—————————

Crumb could be gritty, but finicky about his artistry as can be. (Crumb’s “grit” reminds of Rembrandt prints such as one where a dog is taking a dump while Jesus preaches, or of another where critics at the time griped about how you could see the garter marks on the fleshy thighs of one of his models.)

And Crumb was an avid follower of Kurtzman; the highly-textural “grittiness” of his renderings in the steps of Will Elder and Wolverton in Mad*; the first pages of many of his stories, Weirdo covers, pretty blatant hommages to Kurtzman’s designs.

Compare http://www.celticguitarmusic.com/patton1.gif to http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_tHVfHpnv17g/TCjfMDpLRzI/AAAAAAAAJPg/zRvb1WT6ORU/s1600/war_comics_027_10.jpg , http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-MSSfAhGzM0Q/Tiqq93ZL3uI/AAAAAAAACRU/Hakk4R9Xc3g/s1600/2%2BFisted%2B%252350002.jpg …

(Links to those stories: http://www.celticguitarmusic.com/patton1.htm , http://fourcolorshadows.blogspot.com/2010/06/battle-of-jutland-john-severin-1954.html )

——————————

Because “self-expression” is seen as the highest goal, things like literary craftsmanship and erudition are treated with suspicion if not outright hostility. That stuff is seen as “artifice” and “pretentiousness,” which in this view are qualities that corrupt art. Skillful drawing is still valued–Crumb’s influence has its good side–but I believe that’s because it’s seen as necessary in the “authenticity” pursuit.

——————————

It’s important to differentiate between mere deliberate ugliness (Mike Diana’s work comes to mind) and creativity which rejects slickness, fussy ornamentation, delicate grace in favor of a more “natural,” unrefined effect. The Japanese particularly valuing the latter:

———————————

Wabi and sabi refers to a mindful approach to everyday life. Over time their meanings overlapped and converged until they are unified into Wabi-sabi, the aesthetic defined as the beauty of things “imperfect, impermanent, and incomplete”. Things in bud, or things in decay, as it were, are more evocative of wabi-sabi than things in full bloom because they suggest the transience of things…The signatures of nature can be so subtle that it takes a quiet mind and a cultivated eye to discern them. In Zen philosophy there are seven aesthetic principles for achieving Wabi-Sabi.

Fukinsei: asymmetry, irregularity; Kanso: simplicity; Koko: basic, weathered; Shizen: without pretense, natural; Yugen: subtly profound grace, not obvious; Datsuzoku: unbounded by convention, free; Seijaku: tranquility.

———————————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Japanese_aesthetics

——————————-

Robert Stanley Martin says:

It’s too bad that it isn’t generally recognized that with, say, Harvey Pekar, erudition enhanced the quality of his observations and the judgment used in presenting them.

——————————

Gad, with all due respect to him, when did Pekar ever make a particularly perceptive observation? Even his prose criticism, though it showed a wide erudition and knowledge of the subjects, was by-the-numbers in his perceptions, clunkily written.

*IF you want to see highly-textural “grit” taken to a brilliant extreme in the Fine Arts, check out the paintings of Ivan Albright: http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-2yBVlE4FlVA/TiZ8cCBF8mI/AAAAAAAACLA/UyTas_9_M8A/s1600/albright_12.jpg (clearly a major influence on Joe Coleman…), http://jeninebressner.blogspot.com/2011/07/some-favorite-painters-printmakers-of.html (“This is a detail of an 8-foot-tall painting of a door. He worked on this painting for ten years.”)

Robert, Are you sure Crumb is a fan of L.B. Cole? I don’t recall Crumb ever mentioning him.

Crumb always mentions Barks, Kurtzman, and John Stanley as his comic book favorites.

Holly–

Crumb included Cole’s covers in a list of his favorite comics in TCJ’s Best Comics of the 20th Century issue.

Nice post. Just to be clear, I wasn’t being sarcastic in my comment below the picture of Dash Shaw’s work, I think adapting a reality show that is largely considered trash by the general public and repurposing it into art is pushing comics in a conceptual direction, but I’ll honestly state I don’t like the results. And some of that is because I think it’s all concept with very little craft, in fact, there’s a hostility to craft in Shaw’s work generally that I don’t like. And the concept itself – the idea that if you recontextualize people selling love in a tacky way on television to make it substantial – I just don’t really think it has legs. If someone told you about a book that was just 400 blank pages but the last forty were smears of blood and fecal matter, you might think that sounds like an interesting idea. But I don’t want to read it. The fact that Shaw’s story was in MoME, a highly selective anthology, means it was pushing other artists and their stories out. I kind of see these things as a battle for the soul of comics. I don’t want more Matthew Barneys and Koons’s and Warhol’s. I want more Picassos and Bukowskis.

Is Dash Shaw really comparable to Warhol, in either innovation or craft? I’m not super familiar with Shaw’s work, but it doesn’t really seem like it….

It’s only comparable in that concept is first and execution is a distant second, to the point where with contemporary big-name artists the execution is outsourced to other artists.

Sure…but that just makes it more like film or (many) comics, where there’s a collaborative process….

Finally trying to absorb this…

It seems like in the original post, Caro, you are conflating “craft” (coming out of Nathan’s post) with “ugliness” (and rough expression). Maybe I’m misreading, but I think there’s already too much elevation of “craft” in comics (which I guess is partly the point here, that craft is trumping concept), and even the ugliness of so many underground comics artists (and their inheritors) is still all about craft (I think Crumb’s work is ugly, but I also accept it is well crafted).

I think a certain strain of anti-craft in modern art/alt comics is working against the craft-centric focus in most comics (qua comics and in the dialog around them).

Of course that “craft” focus in comics is often conceptualized as “drawing chops” on one hand or “narrative writing” on the other (which seems to be more what Nathan is going after), eschewing concept in general.

Did that make any point, maybe not. I do think those “Blind Date” pieces by Shaw are poor in conception, but I like the visual craft of them.

I understood the thrust of Schreiber’s argument to be that the craft had to be equal to the demands of the narrative, and that concept too often functions as a substitute for narrative. The Dash Shaw example is actually kind of unfortunate inasmuch as his comic book work is traditionally narrative, where the “Blind Date” stuff is pitched to gallery audiences. I think that’s what Spurgeon meant when he said this was the future of comics… somebody that can move between fields of production without the hand wringing that attends the move from page to comic (think Crumb). Anders Nilsen probably falls into this category as well.

I do wonder if Schreiber and Caro are talking across past each other w/r/t craft. Craghead and English seem close to the sort of conceptually layered post-modern work that Schreiber finds alienating. Both clearly want to see more thoughtfully composed comics, but they seem to disagree about how a thoughtfully composed comic should look/read.

I don’t think we’re really talking past each other, Nate, so much as “slightly disagreeing but not really”. I agree with Nathan and I like what he said but I have sort of a different spin on it: I think craft is very important, but I also think that art can have a dialectical relationship to craft, where some work, especially really experimental work, can eschew craft in order to push craft in different directions.

Austin’s work, for example, engages questions about the relationship of cartooning to non-objective art that I think are really interesting and important. They’re substantive theoretical questions that he grapples with in the medium rather than in criticism, but they are also formal questions — not technique, but form, which is an aspect of craft, isn’t it? Right now that work probably is more conceptual than “crafty” (although I have an original and it’s pretty amazing) — but it’s in a place like Burroughs, not a place like Nabokov. (I don’t think Austin would find that statement derisive…I don’t mean it as such.) I think that kind of work is important for building a comics craft that can handle getting packed with elaborate elegant concepts, just like Burroughs’ work was really important for creating metafiction. I don’t think it’s empty postmodernism in the sense that Matthew Barney is (and I do agree with Nathan on Barney.)

What stood out to me in Nathan’s post was the “concept over craft” business, because to me a hierarchy will always steer us wrong. It must be a dialectic. And I think, oftentimes, conceptual artists see a sexy concept as the end game, as good enough, and it’s just not. It’s maybe good enough for a Hollywood film, but is that really the standard we want to measure against? “High concept blockbuster comics”?

And I think that’s why, despite the fact that I kind of enjoy Warhol-the-Original (who was, for what it’s worth, a fine draftsman back in his ad man days), I agree with Nathan about conceptual art. In practice it’s very much this sort of blunt, vaguely symbolic, marginally kitschy thing that doesn’t really push far enough on its concepts to get out from under its own weight. Concept is really commodified in conceptual art in a way that it just isn’t in literature.

SO I’m just not as pessimistic about “conceptual art” in theory, I think, as Nathan is. Generally he’s right – pithy ideas don’t have the legs to stand up art on. A “high concept” idea is not enough. But for me, if the artist has craft and if the artist has done the conceptual work to tease out the relationship between the concept and the form, then building out those ideas can lead to art that is highly conceptual but also rich with craft. That should be the goal — not some catchy sales pitch concept that reduces art to a soundbite. I definitely don’t think those avant-garde cartoonists (Craghead, Badman, English, Overby, Larmee) are making soundbite comics, and that’s why I think they’re pushing comics in the direction of literary concept rather than visual art concept.

Maybe that makes more sense…I still need to read Derik’s comment up there…

Derik – trying to unpack here – I don’t mean to conflate lack of craft and ugliness. I do think the use of deliberate ugliness/rough expression is frequently (although not inherently) tied up with some oversimplifications about the way aesthetics feeds into concept. Those oversimplifications are present a lot of the time in comics and in conceptual visual art. The oversimplifications are what I’m targeting, not any particular use of the aesthetic per se.

Comics culture likes binaries, and there’s two at play here: narrative chops and drawing chops, and craft and concept. But neither are binary. They need each other. If either one trumps the other, if there’s insufficient attention to the interfaces among them, the work will either be “heavy” — or experimental. I’m ok with it when it hits that genuine experimental level. I’m less ok with it when the binaries themselves become philosophical commitments. So I’m not going to be on the side of something that’s rigidly “anti-craft” — but I honestly don’t see a lot of that in avant-garde comics. I see those comics issuing a challenge to our notions about what craft in comics means and to our notion about how comics craft integrates with and makes possible comics concept, which I think is consistent with what you’re saying. Maybe. Hopefully. :)

That’s where I was going in the original post with the business about it not being an either/or choice between concept and craft…

I have to admit, that Dash Shaw interview in TCJ 300 with David Mazucchelli really put me off Shaw. I feel kind of bad about that — it’s more personal a negative opinion than I like to have about any artist. I guess that’s a risk of interviews-as-criticism…

“which I think is consistent with what you’re saying.”

Yes. Though you said it clearer.

Agreed about that TCJ interview. As I recall (I’d have to reread to be more specific) it kind of turned me off of both of them. Sometimes it’s better not to hear what people have to say about their own work.

Shaw’s chops seem weirdly disconnected – his dialogue is ham-fisted, almost like a pastiche of lower echelon pulp or TV writers, and his drawings, though interesting don’t come together in any elegant way. Both Bodyworld and Bottomless Belly Button read like starter attempts at employing conceptual architecture using tropes and visual styles that are safely experimental (but which appeal to the average comic book reader (or human being, I guess)).

Other than those listed above, Andy Burkholder and Scott Longo are doing very nice comics.

I do hate those binaries, btw, too. Conceptual/Non-conceptual, well-crafted/not-well-crafted, beautiful/ugly – it’s nice to explode them. All extremely good work is a graceful admixture of concept, form, craft, etc.

“I don’t know that Crumb and the others were ever especially aware of Marvel and DC’s output in those days.”

Kim Deitch was certainly aware of early Marvels. A lot of the other underground guys probably were too, but it of course wasn’t a major influence in their work. MAD, Harvey Kurtzman and EC were the biggest influences. The main mainstream comics influence on the undergrounds was not superheroes per se, but the Comics Code Authority which left a huge imprint on most of them as they were growing up.

I think Robert is making gross generalizations given the countless hundreds (thousands?) of reviews the magazine has published. Have “they” promoted a certain point of view or merely reflected what the comics culture has produced? What were the alternatives? To echo Mike, Harvey Pekar, while ok is not a great example of what comics should be for either in the past or in the future.

The case of RAW magazine reflects TCJ’s in some ways. RAW frequently published artists who epitomize the “ugly” aesthetic like Gary Panter, KAZ and Mark Beyer. But given how thin the comics culture was then, it was probably fairly close to publish that or publish nothing at all. The fault likes not so much in the publications themselves, but in the shallow American culture and the near-nonexistent comic book marketplace.

“But in the process they also signaled their distance away from traditional illustration, which was often insistently beautiful. And I think that was intentional as well, because “illustration isn’t comics.”

But many of the comics that came before the undergrounds didn’t resemble anything like traditional illustration. Nor were they generally beautiful. The underground guys didn’t invent crudeness. They were helping perpetuate that particular comics tradition.

“The fault likes [sic] not so much in the publications themselves, but in the shallow American culture and the near-nonexistent comic book marketplace.”

I understand you’re referring to a specific instance, but that’s still an eyebrow raiser right there. I fear this type of attitude is self-fulfilling. When you have this low opinion of an audience, why even try to engage them?

I may be making a gross generalization, but it’s a pretty accurate one. In the mid-1980s an editorial decision was made by TCJ to essentially segregate the better adventure comics reviewers, such as Heidi MacDonald, to Amazing Heroes. In MacDonald’s case, they did this despite her demonstrable interest in all areas of the field and knowing it made TCJ look like there was a “No Girls Allowed” sign hung on the front door. If memory serves, an ME even complained about it in the pages of the magazine.

That was the time that TCJ settled into the general position that underground comics were the font from which all blessings flowed, and the stuff worth covering was material in that tradition. The anti-corporate-comic bias was so pronounced that there was essentially no coverage of Neil Gaiman or Grant Morrison until well into the early 1990s. This was about three years after the rest of the field had taken notice of them. The magazine loosened up a bit after that embarrassment, which happened to coincide with AH‘s demise. From that point on, you might see some discussion of the adventure end of the field in its pages, although the material was usually mocked. Writers go where they feel welcome, and if I was interested in writing about adventure comics, I’m not going to submit spec pieces to a magazine run by Gary Groth. The only time appreciative reviews of stuff from the corporate field occasionally found a congenial home there was during Tom Spurgeon’s or Dirk Deppey’s tenures as ME. Apart from that the emphasis was pretty much always on the U. S. alternative field. The biggest story in comics by far over the last decade was the rise of manga, and the coverage of that work has been conspicuously grudging.

TCJ was able to get away with this from a commercial standpoint because it consistently featured what was by far the best news coverage in the field. When the news operation died, the magazine’s days were numbered. The website is essentially Comics Comics operating under the TCJ logo, and its editors are part-time contractors rather than full-time staff. It’s also going to be a long time, if ever, before you see another print edition.

Kim Deitch was at best a second-tier figure during the underground’s heyday. He didn’t come into his own until the 1990s. I know he likes Kirby, Ditko, and Everett a lot, but I don’t see their influence anywhere in his work.

Who was in the tradition of crudeness before the undergrounds? The art in commercial comics after World War II has always struck me as being pretty slick.

————————–

steven samuels says:

Kim Deitch was certainly aware of early Marvels. A lot of the other underground guys probably were too, but it of course wasn’t a major influence in their work. MAD, Harvey Kurtzman and EC were the biggest influences. The main mainstream comics influence on the undergrounds was not superheroes per se, but the Comics Code Authority which left a huge imprint on most of them as they were growing up.

—————————-

Absolutely! The undergrounders loved and routinely made imitations of EC, despised the Comics Code (Spain did a great short strip where Wertham gruesomely “gets his”), which they saw as the Establishment destroying EC…

—————————–

The most outspoken [underground comic] production against the Comic Code was the defiant series Doctor Wirtham’s Comix & Stories, which appeared around 1977. The colophon read: “We publish good art and underground stories in the E.C. vein, the kind of stuff you know the good doctor would love to hate”…

—————————–

http://lambiek.net/comics/underground.htm

—————————–

Derik Badman says:

…even the ugliness of so many underground comics artists (and their inheritors) is still all about craft (I think Crumb’s work is ugly, but I also accept it is well crafted).

——————————

As fitting with their reverence for EC, most of them — even if their approach hardly exalted beauty — had excellent rendering chops.

(A fine underground-related interview with Rebel Visions author Patrick Rosenkranz at http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/briefings/blog_monthly/2008/03/ )

——————————

Robert Stanley Martin says:

…[TCJ’s] anti-corporate-comic bias was so pronounced that there was essentially no coverage of Neil Gaiman or Grant Morrison until well into the early 1990s. This was about three years after the rest of the field had taken notice of them. The magazine loosened up a bit after that embarrassment, which happened to coincide with AH‘s demise. From that point on, you might see some discussion of the adventure end of the field in its pages, although the material was usually mocked.

…The only time appreciative reviews of stuff from the corporate field occasionally found a congenial home there was during Tom Spurgeon’s or Dirk Deppey’s tenures as ME. Apart from that the emphasis was pretty much always on the U. S. alternative field. The biggest story in comics by far over the last decade was the rise of manga, and the coverage of that work has been conspicuously grudging…

——————————-

I certainly loved The Comics Journal, but that comes across a fair enough summary, as I recall. If the attitude was to champion art comics, I could understand giving them additional focus.

But that, however, didn’t excuse trashing even well-done mainstream comics. David Lapham’s excellent crime series Stray Bullets ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stray_Bullets ), which I thought would be appreciated as an alternative to the prevailing wall-to-wall Spandex cluttering the field, instead received this firebombing of a reception, with none other than Groth himself dumping the napalm: http://archives.tcj.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=175&Itemid=48 . (Eeesh! The actual comic — inventive, richly characterized, its violence messily terrifying rather than choreographed, as far from facilely mainstream as can be — matching that description about as much as the average liberal resembles the image a Rush Limbaugh describes.)

Lapham was a Jim Shooter protegé and loyalist, so that had might have had something to do with it. I don’t think Gary was dishonest as to his opinion, but he might not have taken the time to review it otherwise. Back when he was still writing regularly, he’d trash something just to perpetuate a feud. The most notorious example was that piece he wrote on Robocop 2, which was reasonable enough point-by-point, but you could tell the impetus was the personal animosity between him and Frank Miller at the time.

“I fear this type of attitude is self-fulfilling. When you have this low opinion of an audience, why even try to engage them?”

In the case of the super-hero comic audience, the opinion is justified. Thankfully, that isn’t the only available audience. The alternative scene was almost nothing thirty years ago; clearly an audience has developed since then that one hopes has only gotten larger year by year. But still, is it completely self-sustaining?

“I may be making a gross generalization, but it’s a pretty accurate one. In the mid-1980s an editorial decision was made by TCJ to essentially segregate the better adventure comics reviewers, such as Heidi MacDonald, to Amazing Heroes.”

Yeah, that is terrible. And really puzzling because they never did completely stop reviewing mainstream books in the main magazine.

“The anti-corporate-comic bias was so pronounced that there was essentially no coverage of Neil Gaiman or Grant Morrison until well into the early 1990s. ”

That likely hurt them commercially. But then again, the magazine was frequently late over the years. But they did get to Alan Moore early enough several times at the peak of his mainstream visibility. I still don’t see what this has to do as far as the craft/concept debate. I guess it would be a problem if one thinks that Gaiman/Morrison were all that great to begin with. They’re ok, but if that’s all the mainstream scene could muster, then I’d say the bias against it was fully justified. Granted, it’s a shame that manga couldnt’ve been covered more, but that bias is also due to the lack of available bilingual writers.

So it again begs the question. In a tiny scene where one has to fight tooth & nail just to stay afloat, what would have been the alternatives? Pekar, Gaiman and Morrison are not enough to qualify as viable aesthetic alternatives.

“Who was in the tradition of crudeness before the undergrounds? The art in commercial comics after World War II has always struck me as being pretty slick.”

Not all of those comics were slick. Those 50s detective comics were certainly crude. At least the off-brand titles were. For me the undergrounds also harken back to the late-30s/early 40s comics in their free-for-all propulsion. Just like how you can hear the girl groups in the Ramones and Sun Records in Television’s “Marquee Moon.” There isn’t a direct connection to the crudity of the past, but at least a definite echo of it whether the artists were conscious of it or not.

And a small defense of the undergrounds. Like Bill Randall said, yes they were generally too lowbrow. And yes, the EC influence was pernicious. But with artists like Dan O’Neill, Frank Stack and the woefully neglected “Wimmin’s Comix” artists one cannot discount their validity. Robert Crumb has written stories that are at least as worthwhile as anything Pekar ever wrote. The final “Mode O’Day” story in Weirdo (in the Complete Crumb Comics #17) is a good example of that.

Funny hearing this about TCJ not including Gaiman early on, as the first issue I bought of the magazine had Gaiman on the cover (mid-90s I guess).

————————–

Robert Stanley Martin says:

…TCJ was able to get away with [ignoring/trashing mainstream comics] from a commercial standpoint because it consistently featured what was by far the best news coverage in the field…

—————————-

Let’s not forget what for me and many others was the crowning glory of the magazine: its lengthy, substantial interviews, routinely featuring “old masters” and mainstream mainstays of the art form.

To get a proper idea of the “mix,” here’s a List of Comics Journal interview subjects: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Comics_Journal_interview_subjects . A fine mix of alternative, underground, mainstream, Old Masters; as shown by segments in the alphabetical list such as…

* Chester Brown ([Issue #] 135, 162)

* Ed Brubaker (263)

* Ivan Brunetti (264)

* Frank Brunner (51)

* Bob Burden (268)

* Kurt Busiek (188, 216)

* John Byrne (57, 75)

* Eddie Campbell (273)

* Milt Caniff (108)

or…

* Denny O’Neil (64)

* Kevin O’Neill (122)

* Gary Panter (250)

* Harvey Pekar (162)

* George Pérez (79)

Steven–

They never stopped reviewing them, but the tenor was generally, “Look at this piece of crap I accidentally bought last week.”

There was no rhyme or reason to any of it. When the mainstream review coverage was at its nadir, this is what you didn’t see reviews of but should have:

–Neil Gaiman’s Sandman and Black Orchid.

–Grant Morrison’s Animal Man.

–Jamie Delano’s Hellblazer.

–Todd McFarlane’s Spider-Man.

–Rob Liefeld’s X-Force and New Mutants.

–Jim Lee’s X-Men, or any of his Image work.

–Chris Claremont’s X-Men finale. (They could have killed two birds with one stone with that, as Lee drew it.)

–The Death of Superman.

–The Moore, Gaiman, Sim, and Miller issues of Spawn.

–Frank Miller’s Elektra Lives Again.

–Frank Miller’s initial Sin City serial. (Fiore reviewed the second one in his column.)

–Mike Mignola’s initial Hellboy material.

If you don’t consider Fiore’s columns, the ’92 mainstream-comics ghetto issue, or the “Batglut” article that plagiarized Pauline Kael left and right, there’s a good deal more.

There was also next to no review coverage of the initial manga translations that were released beginning in the late ’80s (Akira, Lone Wolf and Cub, etc.). And as it was translated, I don’t see how the lack of bilingual reviewers was a problem.

By the way, I happen to think a good deal of this stuff is crap, but given its high profile, it should have been reviewed. That it wasn’t is a significant editorial failure.

I admit this is a tangent from the craft/concept debate. But it does illustrate TCJ’s myopia, which I do think is a big part of the problem. Groth and company are largely unable to think outside of their own box, and the magazine’s prominence made this pernicious.

Derik–

They tried to make up for the Gaiman oversight with multiple feature-length interviews in ’93 and ’94. But it was very belated. Gaiman made his first big splash in ’88 with Black Orchid. By the end of ’89, he was the most respected talent then working at Marvel or DC.

By the way, I don’t know if Caro agrees, but I think Gaiman is very relevant to the craft/concept debate. His material is much more sophisticated than anything I’ve seen from all but a handful of the major indy talents of the last quarter-century.

Mike–

There are a lot of great interviews, but there aren’t many noteworthy ones with mainstream talents in between Kim Fryer and Tom Spurgeon’s tenures (from #118 to #171). And of those, such as the ones with Alan Moore and Tim Truman, a good portion were conducted because the talents were taking an indy direction with their work, however short-lived. Apart from the news coverage, TCJ turned its back on almost the entire field during that time.

Robert: thanks for reminding me why I once liked the Journal.

Ha!

However, TCJ was a trade magazine back then, and it wasn’t acting like one with its features material. It handled those sections like it was an arts journal, of which there’s no expectation of currency or an encompassing treatment of the field’s output. The comprehensive news coverage made the magazine seem completely schizo.

And if you ignore the news coverage, it didn’t really work as an arts journal. They were actively hostile to theory-based criticism. What they wanted and published was journalistic criticism of the kind you’d see in a trade publication or the New York Times Book Review.