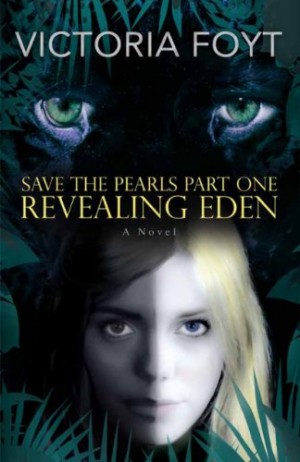

Whether in the American Revolution, Schindler’s List, or Star Wars, Americans have always had a deep and abiding love for tales of oppressed white people. In her new YA novel, Revealing Eden, Victoria Foyt takes that insight and runs with it as fast and as far as impressively insipid prose can take her. In the far future, solar radiation has become exponentially more dangerous, and those without the melanin to withstand it are second-class citizens. Our heroine, Eden, is white and, therefore, doomed to eugenic culling unless she can convince a black man to mate with her and give her dark-skinned babies. Soon she is embroiled with the fascinating Bramford, a black scientist who has had his DNA spliced with panther, eagle, and anaconda genes, turning him into an earthy, atavistic archetype. Luckily, in Foyt’s world, black people are in charge, so Bramford’s evolutionary descent has nothing, nothing, nothing to do with sexualized animalistic fantasies about black men. Shame on you for even thinking so.

Whether in the American Revolution, Schindler’s List, or Star Wars, Americans have always had a deep and abiding love for tales of oppressed white people. In her new YA novel, Revealing Eden, Victoria Foyt takes that insight and runs with it as fast and as far as impressively insipid prose can take her. In the far future, solar radiation has become exponentially more dangerous, and those without the melanin to withstand it are second-class citizens. Our heroine, Eden, is white and, therefore, doomed to eugenic culling unless she can convince a black man to mate with her and give her dark-skinned babies. Soon she is embroiled with the fascinating Bramford, a black scientist who has had his DNA spliced with panther, eagle, and anaconda genes, turning him into an earthy, atavistic archetype. Luckily, in Foyt’s world, black people are in charge, so Bramford’s evolutionary descent has nothing, nothing, nothing to do with sexualized animalistic fantasies about black men. Shame on you for even thinking so.

Revealing Eden is unusually crass in its take on race, but its general methodology has a longstanding pedigree in sci-fi and fantasy. You need only think of that ham-fisted Star Trek episode in which the aliens with faces that are white on the right side are oppressed by aliens with faces that are white on the left side, or the ham-fisted Next Generation episode in which the crew finds a planet where women rule over men.

Or, for a more recent example, try the film In Time, a parable in which fungible time has replaced money as the currency of choice. Thus, the rich live forever on horded time and the poor have to beg, borrow, steal and run for every second. The movie is clearly intended to be a comment on our crappy economy and growing inequality — but it’s a comment shorn of any mention of the ways in which that inequality continues to be bound up with race. There is, as far as I can remember, only one black character in the film; a long-suffering wife whose (white) husband is an alcoholic. The unfair distribution of time serves as a metaphor for real-world injustice — but does the metaphor highlight those real-world injustices, or does it deny them? Is it possible that the sci-fi setting is just a way to do a story about economic oppression without the inconvenience of having to feature black leads?

Similar questions arise in the three most successful YA series of recent memory: Harry Potter, the Hunger Games and Twilight. All make extensive use of metaphor to discuss racial prejudice — or to avoid discussing racial prejudice, as the case may be. In Harry Potter, (bad) wizards are prejudiced against muggles; in the Hunger Games, the people of the Capitol are prejudiced against the people of the Districts; in Twilight, vampires and werewolves are prejudiced against each other.

All these series come down squarely against discrimination, which is nice as far as it goes. That isn’t very far, however. For example, wizards in Harry Potter really are superior to muggles; no one really denies that. The only point at issue is whether muggles should be killed outright (as Voldemart believes) or whether they should be kept in perpetual ignorance for their own benefit (as the “good guys” believe.) Rudyard Kipling might approve, I suppose, but, to put it kindly, it’s hard to see this as a particularly insightful take on contemporary race relations. And I will avoid discussing the lovable house elf servants, who adore their own enslavement — a fantasy underclass entirely composed of Gunga Dins.

Hunger Games and Twilight are arguably less clumsy, but not by much. Suzanne Collins avoids discussing race by the simple expedient of not discussing it. Her main character, Katniss is possibly biracial, but it’s so downplayed in the book that Hollywood had no problem casting a white actress in the part for the film. In Twilight, there are many Native American characters, and the books deal forthrightly with prejudice directed against those characters. But all that prejudice is because the Native Americans are werewolves; there’s barely a hint that Native Americans who are not werewolves might occasionally be discriminated against. And, of course, Meyer, like Foyt, cheerfully deploys the stereotype of the animalistic, emotional, virile lesser races. Just because discrimination is bad doesn’t mean you can’t have some fun with it, right?

In all of these cases, the problem is that oppression is seen as a (simplistic) structure, rather than as a history. For Foyt, Rowling, et. al, you condemn racism by saying, “Hey! Racism is bad!” For none of them is there a sense of historical inequalities as a living and inescapable presence. Victoria Foyt’s main character, Eden, reads Emily Dickinson, but not Langston Hughes; nobody in Harry Potter compares Voldemort to Hitler; nobody in the Hunger Games has heard of Che. Oppression in all of these series has a now, but no yesterday. Sci-fi and fantasy, apparently, means a world without a past.

It doesn’t have to be that way. As just one counterexample, consider Octavia Butler’s Dawn, the first book of her Xenogenesis trilogy. The novel is set after a nuclear apocalypse. Most of the world has been destroyed, and earth’s few survivors have been rescued by a tentacled alien race known as the Oankali. The rescue is not entirely philanthropic, though. The Oankali are genetic manipulators; they want human beings for their genetic material. Or, to put it another way, they want to mate with our women — and also our men.

The main character in Dawn is an African-American woman named Lilith. You might think that in a future where most of humanity is dead and aliens have inherited the earth, race wouldn’t matter. But, as Butler shows, that would be naïve. Race matters a lot. It inflects other humans’ reactions to Lilith when they are asked to follow her leadership. It inflects the aliens themselves, who assume that Lilith will want to mate with one man because he is black. And it inflects Lilith’s reactions as well, both in her loyalty to her species against an imperial invader, and in her eventual acceptance of difference and, ultimately, of interspecies integration.

Butler doesn’t forswear analogy. The Oankali are in some ways very much like human imperialists — the European invaders conquering the New World. Similarly, mating with the Oankali is comparable to interracial relationships. But the metaphors don’t erase the past; instead they complicate it The imperialists are also saviors. Interracial marriage is both a betrayal of the race and the promise of a new and beautiful future. A future in which, not incidentally, the children of a black woman save humanity.

Dawn demonstrates that metaphor is not, or at least should not be, amnesia. Foyt wants to say that white is black without making any effort to think about either white or black. As a result, her world — and to a lesser extent, the worlds of Rowling, and Collins and Meyer — have an air of rather nervous blandness. Butler, alone in this company seems to realize that even in a different world, we can’t escape what has already happened in this one.

I don’t see Xenogenesis as YA, just in case anyone who (like myself) doesn’t read YA might be curious about it. That probably has a lot to do with why it’s less bland than the other books you mention here. I’m sure there are exceptions, but YA tends to simplify things doesn’t it?

No, I don’t think YA simplifies things any more than adult media like In Time or Star Trek. The Narnia books and Roald Dahl and the Hobbit and Alice in Wonderland are substantially more sophisticated than any number of adult works.

Xenogenesis isn’t exactly YA — it wasn’t marketed that way I don’t think — but it has a lot of the hallmarks. The books are short, for one thing, and (especially book 2 and 3 in the series) focus on coming of age narratives. I think in a lot of ways they’re a cross between high-art sci-fi (like Delaney) and YA. I kind of love that about them. (And while I certainly like Xenogenesis more than most YA, I like it more than Delaney too.)

Ha, well, that’s certainly true, but while Dahl, the Hobbit and Alice might be a good deal more sophisticated/complex than the vast majority of “adult” lit, they’re more “simplified” than the best of adult lit. No disagreement about their worth or value, but they are aimed at kids, after all. I suppose a better way of saying this is that they’re issues are a bit more precise, more focused. I love rereading The Giving Tree, but it doesn’t cover as much ground as Xenogenesis. (There’s value in that — not trying to dismiss adults loving to read kids books more than I.) Maybe that has something to do with why Harry Potter and the like aren’t as morally complex as you’d like them to be.

Actually I think your average YA novel is more likely to deal with really thorny issues, like identity, injustice, depression, etc, than your average adult novel. YA thinks harder about “what is right” than adult fiction which is largely escapist or set in an already morally compromised universe.

I could back this up, if you are skeptical…

For instance, I can’t think of any other reason for the Octavian Nothing books to have been classified as “YA” – have you read them? they are really advanced! – besides the fact that YA is the only place you can have a serious discussion about pseudo-science and attitudes toward race in eighteenth century America, written by a white woman.

Butler was definitely a trailblazer. I am not a huge fan of her writing, but you may have convinced me to give Xenogenesis a try. (Although I’m not sure how anything she’s written could be better than Delany!?! The Neveryon series features compelling analogies about race and power that I really enjoy. And also dragons.)

I haven’t read Neveryon. I find Delany’s “sci-fi — it can be modernism too!” thing off-putting — if somebody’s going to write pulp, I want them to deal with the fact that it’s pulp, not pat themselves on the back for turning it into high art. But that’s me…Caro loves Delany.

Yeah, I tend to think Delany is our most important living American writer. And our most important living black writer, and our most important living gay writer, and our most important living literary critic. He’s sort of an all-purpose nexus of awesome.

But hyperbole aside, he does, very much, deal with the fact that sf is genre, and also very much with the pleasures of genre, which he links to sexual pleasure as well as to pleasure as a source of empowerment – but I think he’s also much more postmodern than modernist. His point is not to turn genre into high art, but to collapse any separation between the pleasures of art and those of genre (read the essay on paraliterature!)

I don’t know if genre counts as pulp in your formulation there, Noah — I mean, he isn’t embracing the idea that it’s all crap and that literary craft is besides the point and a waste of time, but he does acknowledge the ways in which genre is pleasurable for reasons that are different from conventional literature. He just thinks — and proves — that those reasons and those pleasures can exist directly alongside some of the more conventional literary pleasures as well.

The person who pats themselves on the back for turning genre into high art is Thomas Pynchon…Delany’s pretty seriously loyal to genre. I’m not sure what you’ve read — maybe I’ve given you the wrong idea about him — I don’t talk about Pynchon because he’s so freakin’ DULL, so Delany’s always my go-to for examples, but he’s definitely not that sort of literature, where all the pleasure is abstracted into some series of formal, naval-gazing tricks…

I like Butler, too, Qiana, but she’s more accessible and less literary than Delany. I don’t think she’s engaged with literary pleasure at all, really. It’s pretty straight SF — it’s GOOD SF, but it’s not Delany. I always found her a little didactic, honestly, although not as didactic as the worst excesses of that in SF. Didacticism is one of the pleasures of SF I suppose LOL. It’s definitely one Delany eschews. (Hope that doesn’t entirely contradict my previous comment!)

I can’t remember if it was her or Delany who complained about this, but one of them commented that they keep getting put on panels together, even though the only thing they have in common is that they’re black. If you’re looking for Delany-like work, don’t go to Butler. But she does have merits of her own…

Yeah…your description of what Delany is doing seems reasonable, but still sounds to me like a very abstract and literary way of approaching genre. I think Philip K. Dick manages to go through genre to art rather than the other way around, which I find much more congenial since contemporary literary fiction gives me stomach pains. Butler’s less convoluted in her approach to genre than either PKD or Delany, I think — more like Ursula K. LeGuin, maybe. I wouldn’t say she’s not engaged in literary pleasures…but she certainly seems less like she’s writing to get a grant. Which I appreciate about her.

I’ve read a couple of Delany’s books. Stars in My Pocket Like Grains of Sand has a great opening section and then gets progressively less interesting, ending in a kind of third-rate John Barth mess. I also read a book whose title I can’t remember about a viral language which takes people over which seemed like really simple-minded pomo nonsense — the sort of thing Grant Morrison would throw out in a panel or two and would be enjoyable as such, but which was really significantly less fun as the basis for an entire novel.

Maybe I should try something else….I have some similar problems with Joanna Russ, who I know you also like a lot. I loved the first part of We Who Are About To, but the following stream of consciousness bit just made me feel strongly that she wasn’t Virginia Woolf. Read a couple other things by her which I thought were okay….but overall I’m much, much more into the Earthsea books, or PKD, or C.S. Lewis’ space trilogy, or Butler’s Xenogenesis; things that don’t smack so strongly of the academy.

Caro, I agree that Butler is more accessible – KINDRED and BLOODCHILD are terrific texts to teach and the issues are fairly clear and a little didactic as you say, though not always neatly resolved. My problem is mostly with her writing style, which has always felt too wooden and stilted to me and I also find that the protagonists in her fiction don’t seem to vary much in terms of their motivations and personality. Still, she is a solid storyteller.

So I hate to gush, but I think “all-purpose nexus of awesome” is pretty accurate when it comes to Delany…! I agree that he is a different kind of sf/fantasy writer than Butler; they don’t share the same goals, the styles are different. In addition to his interests in the pleasures of genre, I am really fascinated by how he uses metafictional devices in ways that invite and reward countless re-readings. This must be what smacks so strongly of the academy! I guess I’m guilty as charged on that one.

Noah, you should try NOVA – maybe that one won’t give you stomach pains.

Well, I just read Frederic Jameson’s Postmodernism, which I really liked, so it’s not like I’m anti-academy in all things. Literary fiction in the academy is a tough sell for me, though. But maybe I’ll try NOVA….

——————————

subdee says:

Actually I think your average YA novel is more likely to deal with really thorny issues, like identity, injustice, depression, etc, than your average adult novel. YA thinks harder about “what is right” than adult fiction which is largely escapist or set in an already morally compromised universe.

I could back this up, if you are skeptical…

——————————

I believe you! The intended readership has not been burned out by the endless stresses and damn-near-inescapable moral compromises of adulthood.

——————————-

Caro says:

Delany…does, very much, deal with the fact that sf is genre, and also very much with the pleasures of genre, which he links to sexual pleasure as well as to pleasure as a source of empowerment – but I think he’s also much more postmodern than modernist. His point is not to turn genre into high art, but to collapse any separation between the pleasures of art and those of genre (read the essay on paraliterature!)

I don’t know if genre counts as pulp in your formulation there, Noah — I mean, he isn’t embracing the idea that it’s all crap and that literary craft is besides the point and a waste of time, but he does acknowledge the ways in which genre is pleasurable for reasons that are different from conventional literature. He just thinks — and proves — that those reasons and those pleasures can exist directly alongside some of the more conventional literary pleasures as well…

———————————

From Caitlín R. Kiernan’s blog:

———————————

Jan. 25th, 2012:

Having lately read so much dull, flavorless sf, I’d really like to write a bit of sf that, at the very least, can be called neither flavorless nor dull. Thing is, so much of that bad sf I’ve been reading is bad not because, I suspect, the writers in question are necessarily bad writers. I know that some of them aren’t. It’s because good sf – especially that of the futuristic variety – requires the author to have a firm grasp of sociology, psychology, linguistics, pop culture, economics, history, politics, and never mind the fields of science and technology relevant to the story at hand (besides sociology and psychology, I mean). You have to know, or at least be able to lay your hands on, all these disparate sources of data if you are to imbue your story with the least jot of authenticity, and then you have to start juggling them, and keep it all in the air while you write (I suppose this is done with the toes, since the hands are occupied), snatching the information you need as you need it. Mixing and matching, splicing and melding.

Jan. 22nd, 2012:

I read Jack McDevitt’s “The Cassandra Project” (2010) and Vylar Kaftan’s “I’m Alive, I Love You, I’ll See You in Reno” (also 2010). Both had kernels of magnificence trapped deep inside. Both were far too short, felt like outlines, and were almost entirely devoid of voice. I’m not sure if it’s true that “Science fiction is the literature of ideas” (not sure, either, who first said that, and if you can figure it out for me, you get a banana sticker), but I don’t think they meant that all you need is an idea*. At least, I hope that’s not what he or she meant. I look back to Philip K. Dick, William Gibson’s early work, Ray Bradbury, Jack Vance, Robert Silverberg, Ursula K. Le Guin, Frank Herbert, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., Michael Moorcock, Harlan Ellison…long, long list…and there is style. Voice. Good writing. Not this no-style style. From recent samplings, I fear that too much of contemporary science fiction has all the flavour of a stale communion wafer, and is just as flat. Sorry. Gratuitous (but true) Catholic reference. Where are our prose poets? Why doesn’t the language used to convey the idea matter? It’s not entirely true to say it’s completely absent from contemporary sf. We have the brilliance of China Miéville, for example. But for fuck’s sake, the short fiction I’m reading…communion wafers.**

Oh. By the way. Yesterday was National Squirrel Appreciation Day [ http://www.nwf.org/News-and-Magazines/National-Wildlife/Outdoors/Archives/2011/Squirrel-Day-Activities.aspx ]. I shit you not. Let’s hear it for Sciuridae.

* Possibly, it was Pamela Sargent. Or, possibly, she appropriated it from Isaac Asimov.

** Near as I can tell, this has always been the case with “hard” and “military” sf.

———————————

http://greygirlbeast.livejournal.com/

——————————-

Caro says:

I can’t remember if it was [Butler] or Delany who complained about this, but one of them commented that they keep getting put on panels together, even though the only thing they have in common is that they’re black…

———————————-

Convention Organizers: “What, that’s not enough of a reason?”

———————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

I think Philip K. Dick manages to go through genre to art rather than the other way around, which I find much more congenial since contemporary literary fiction gives me stomach pains.

____________________

Neatly and perceptively put.

My first copy of Dawn portrayed the protagonist as a white woman, as seen in this post:

http://thebooksmugglers.com/2010/02/cover-matters-on-whitewashing.html

I suppose one could argue that the standing white woman is meant to be one of the white women who assist in the “awakening” procedure shown here, but c’mon. Although Lilith’s dark skin only gets a couple of blink-and-you’ll-miss-them mentions in the first book.

“in the Hunger Games, the people of the Capitol are prejudiced against the people of the Districts”

Nitpick: this is yet another Hunger Games nod to the Roman Empire, right?