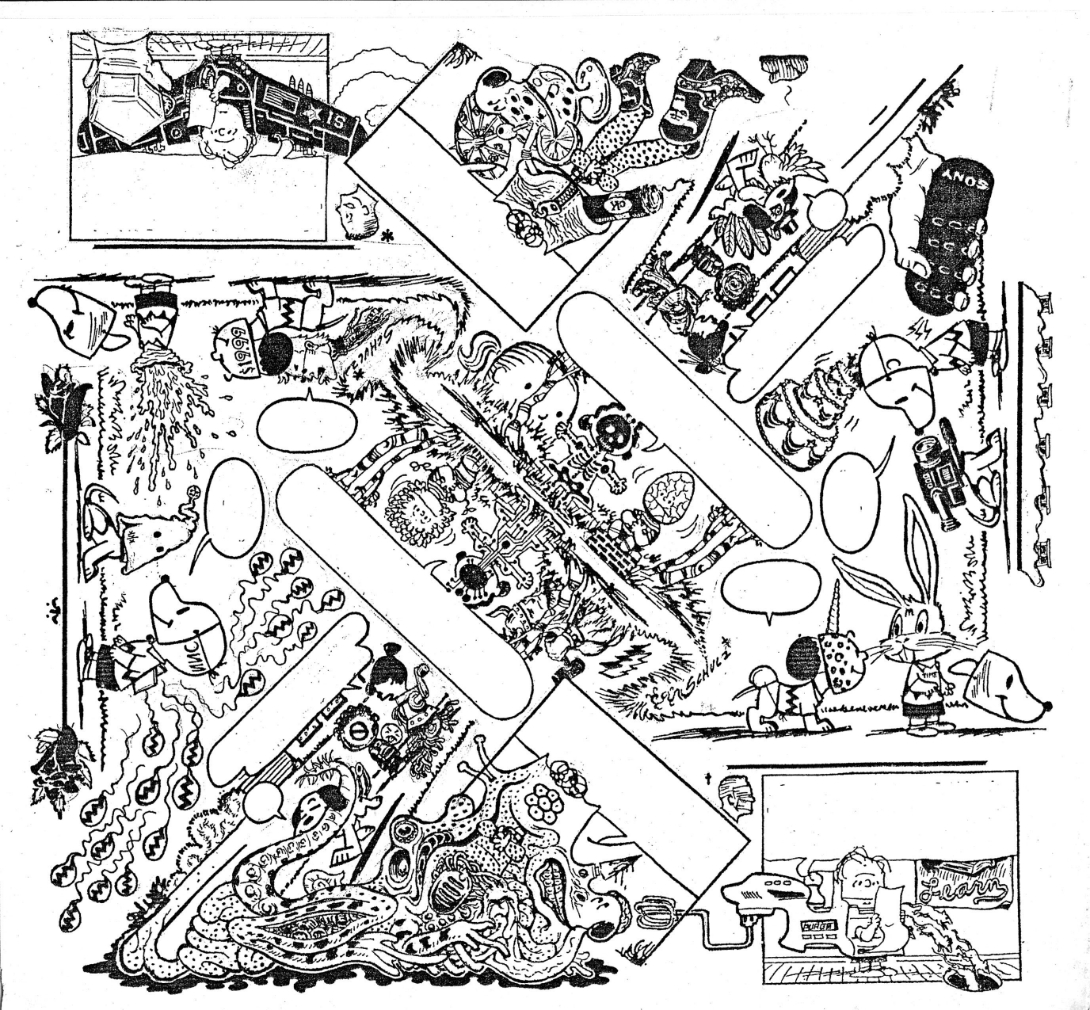

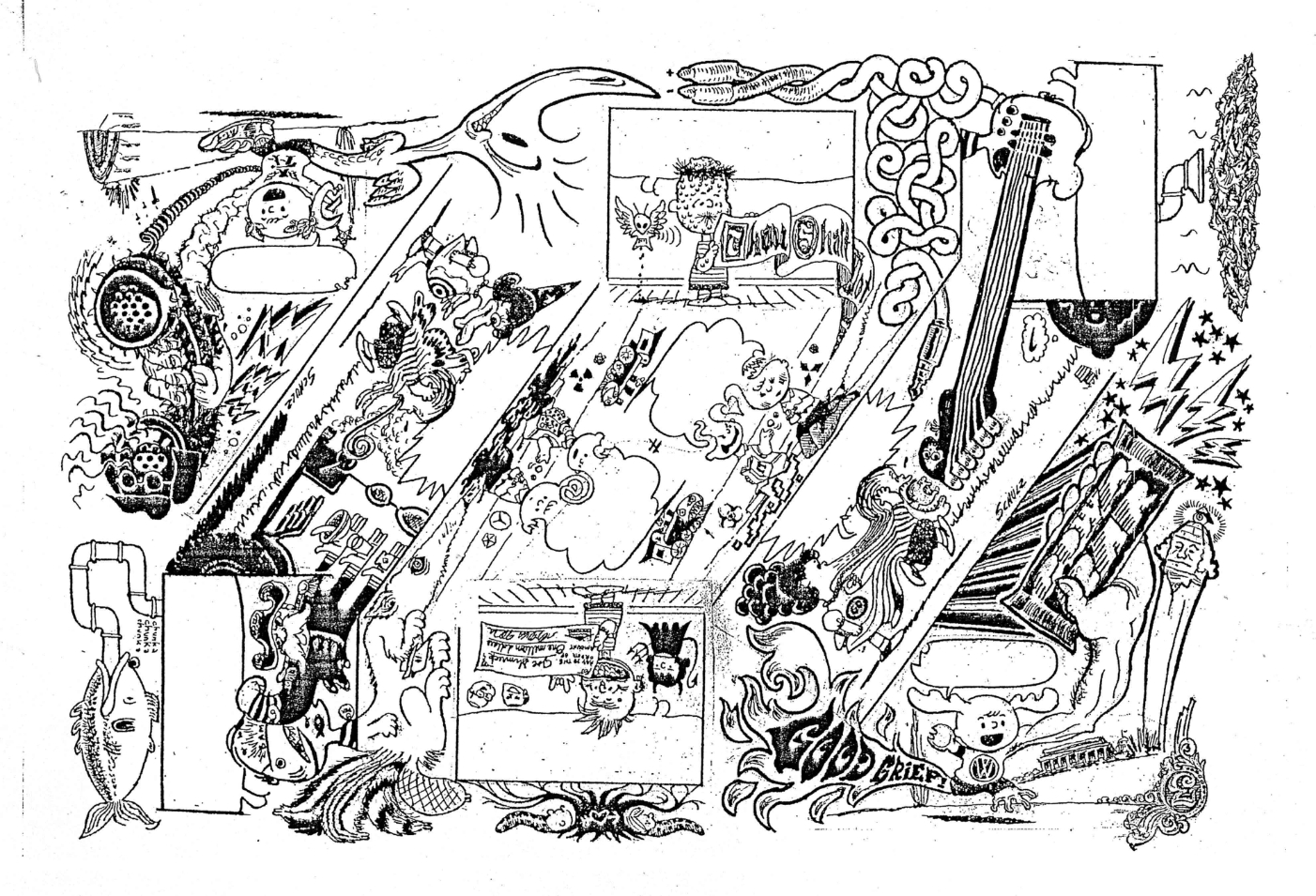

Above is a art project Bert Stabler and I worked on together. I wrote the words and he drew the image.

Except, as you’ve probably noticed, there are no words. When it came down to it, Bert decided that the pictures looked better without the text. So he took them out.

In some versions of comicdom, this could be seen as a cardinal sin. As Joe Matt says, “”I’ve gotta draw minimally to serve the storytelling! The writing always comes before the art!” Similarly, Ed Brubaker argues “I’ve always felt that the writing was far more important than the artwork… As long as the art supports the story…” It’s hard to see how Bert could have more thoroughly violated these precepts.Not only does his art not serve the storytelling, but in the name of the art, he actually went ahead and removed the words altogether!

Of course, in our project, the words were always subordinated to the drawing; Bert did the artwork first, then I provided words…and then he decided the words didn’t fit (in some cases literally — too much text for the boxes.) But that merely underlines the point that art here was not subordinated to storytelling.

Bert’s piece takes several steps towards abstract comics. Appropriately enough, Andrei Molotiu has taken on a lot of these issues at his Abstract Comics blog (from which I pinched the Matt and Brubaker quotes). Specifically, Andrei has argued that art in comics should not be, and often is not, subordinated to the demands of text or narrative. Speaking of the art-must-follow-story meme, Andrei says

This is exactly the logic of illustration–which is a form of logocentrism… And here we can expand the discussion beyond abstract comics, which occupy only the extreme position (like “purely harmonic music”) in a wider range of art that exceeds narrative demands.

In another post, Andrei goes on to look at some examples of non-abstract, art-superfluous comics.

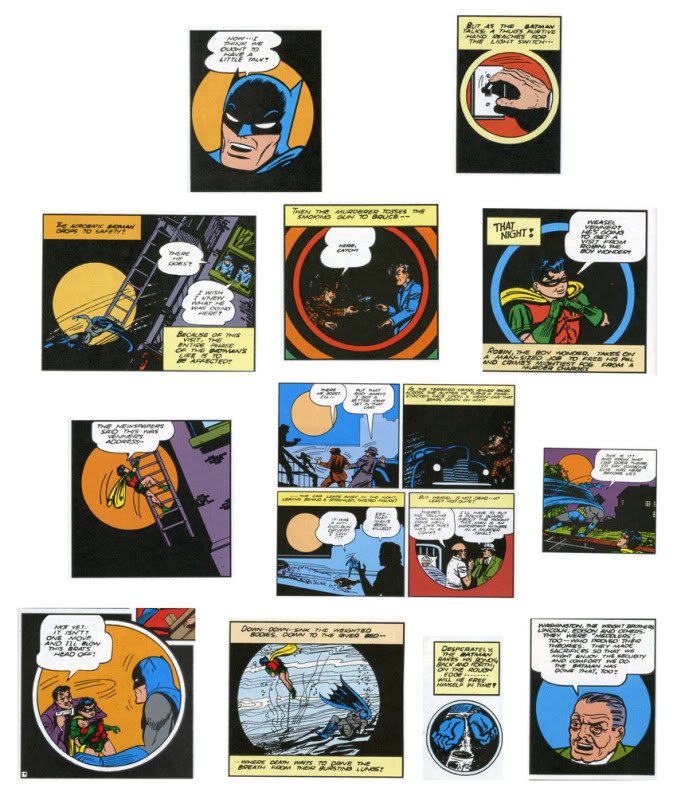

For instance, he talks about a Bob Kane story from 1941, in which Kane used a ton of circular panels, as Andrei shows:

Andrei goes on to say:

Now, what does this mean? Probably nothing. (Which is not to say it’s not significant; just that it’s probably not meant to mean.) One can obviously draw the parallel between the circular panels and the moon–but the resulting interpretation (Batman as creature of the night, etc.), would be generally valid for ANY Batman story: so why specifically this one? Similarly, one can find some connection to the closing words of the story, where Bruce Wayne, with a wink, tells Commissioner Gordon: “I guess the life of Bruce Wayne does depend quite a bit on the existence of the Batman!” There is a kind of circularity implied there, I guess, and we can then claim the circularity is echoed formally in the art… And yet, if that’s the great realization, the theme of the story–again, the Bruce Wayne/Batman dichotomy is a constant throughout the strip. Why this story specifically?

I don’t know. Maybe Bob Kane had a brand new compass he had purchased the day he drew this story, and he was just dying to use it. But my point here is: I’m not so much interested in fully motivated signs, portentous (a la Wagner) leitmotifs charged with meaning as you can find in, say, “Watchmen” or “The Dark Knight Returns”–works in which their creators seem fully in control of their formal language, in which every single (or almost) signifier can be seen as adding something to the story’s theme. Rather, I’m interested in what, at this point, may be called automatisms, tics perhaps, that nevertheless affect our experience of the comic.

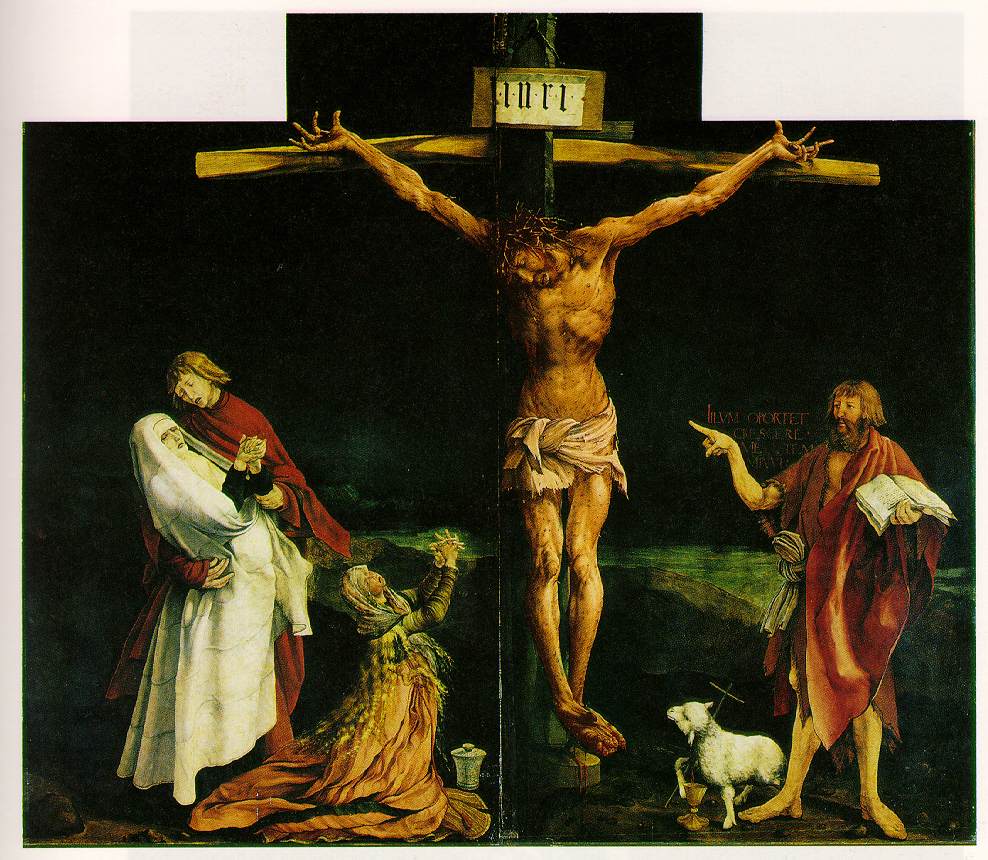

Andrei is drawing a distinction between formal elements that can be collapsed into the theme and formal elements that are tics, excesses over meaning. As an example formal elements linked to theme, you could perhaps take this Gruenwald painting, where the idiosyncratic formal use of scale illustrates the phrase “He must increase, but I must decrease.”

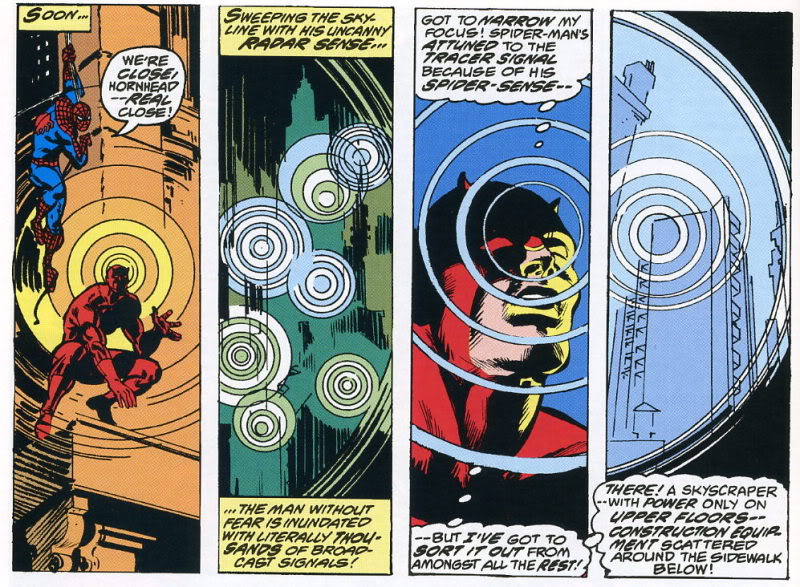

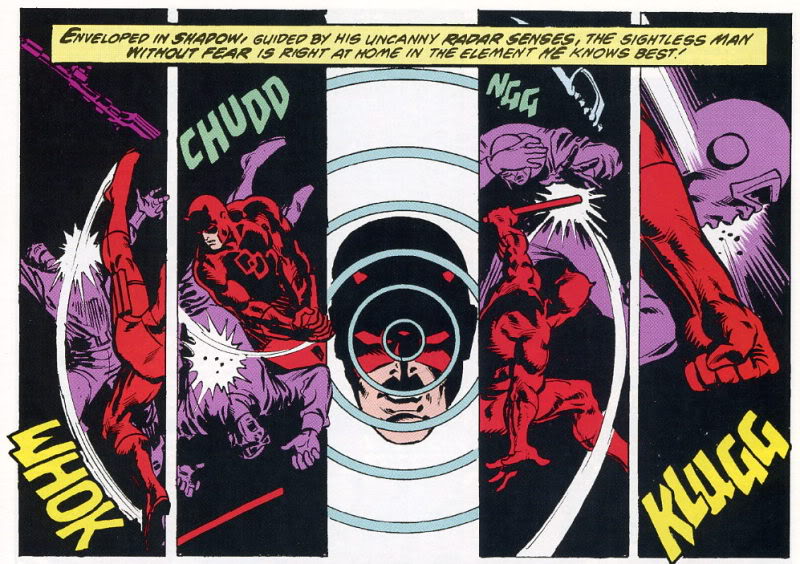

And as an example of formal tics that do not link to theme, you could take the insistent circular repetitions in the Frank Miller Spider-Man/Daredevil crossover which Andrei analyzes.

In Gruenwald, the formal elements relate directly to the spiritual meaning; in the Frank Miller, the circles are just a way of organizing space; an abstract, musical surplus, which contribute to pleasure or experience without, Andrei says, contributing to narrative or meaning.

The question I have here though, is this: are narrative and meaning synonymous? Obviously they aren’t; Gruenwald’s painting isn’t a narrative, but it’s intended as an illustration of a thought or a metaphysical insight. But what about in Miller?

Perhaps one thing that the circular motif does is to insist on its own integrity. It draws a border; looking at those images, it’s hard to avoid the sense of space. In both of the sequences form Miller above, the words are literally pushed off to the edge, allowing the circles to spread — Daredevil’s senses, his “sight”, reaches out across the page, marginalizing the text. Logocentrism is (again, literally) replaced by iconocentrism. This is the case even in instances where the text is more interspersed with the circles, as below.

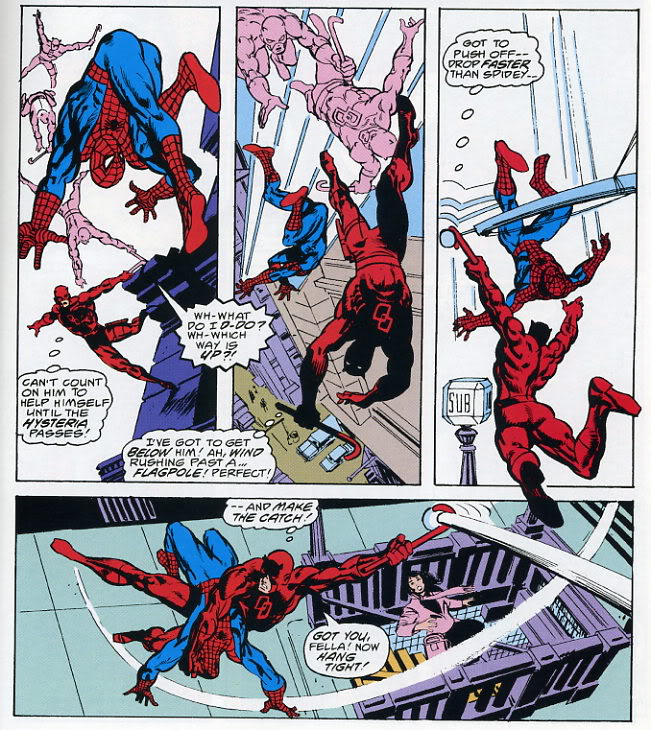

The spinning multiple figures against the whiteness demand attention. It draws you down into an excessive, vertiginous whirl of motion that makes the banal text (“Got you fella! Hang tight!”) seem like the superfluous bit.

Thus, the image spilling over the words does not exceed meaning. Rather, its meaning (or one meaning) is the excess itself. When Andrei says illustration is excess, he is not illustrating the way in which illustration does not mean; rather, he’s illustrating that very meaning, which is excess. The circle is a hole in narrative — a vortex that escapes the story’s staid linearity and in its place spins out an ever-expanding circumference of pleasure.

Bert’s excision of text can also be seen as a kind of deliberate overtopping, or annihilation, of narrative content.

In Bert’s drawing, the Peanuts characters flow and morph, losing their coherence as they dissolve into a kind of post-modern iconic glop. They don’t cease to mean; rather, their meaning is unanchored from its original context and sent oozing along the chain of signifiers. So Schroeder turns into a guitar which turns into tombstones haunted by a cute little death and Linus and Lucy fuse into a single terrified/terrifying blob of torment and tormenter. It’s a violent detournement — and the violence is not only in the drawing, but in the (lack of) text. The Peanuts characters are all caught in the boiling cauldron of narrative meltdown, and their blank, stunned, failed efforts at speech only emphasize their tortured transformation. The speech bubbles hang emptily in the design — the last, sad trace of the vanished stability of logos, as around them rages the free-associative chaos of the image.

_____________

In the examples so far, Andrei’s conception of the visual as excess (beyond meaning in his formulation, of meaning in mine) has worked fairly well. I think it is possible to find instances that call it into question though. For example:

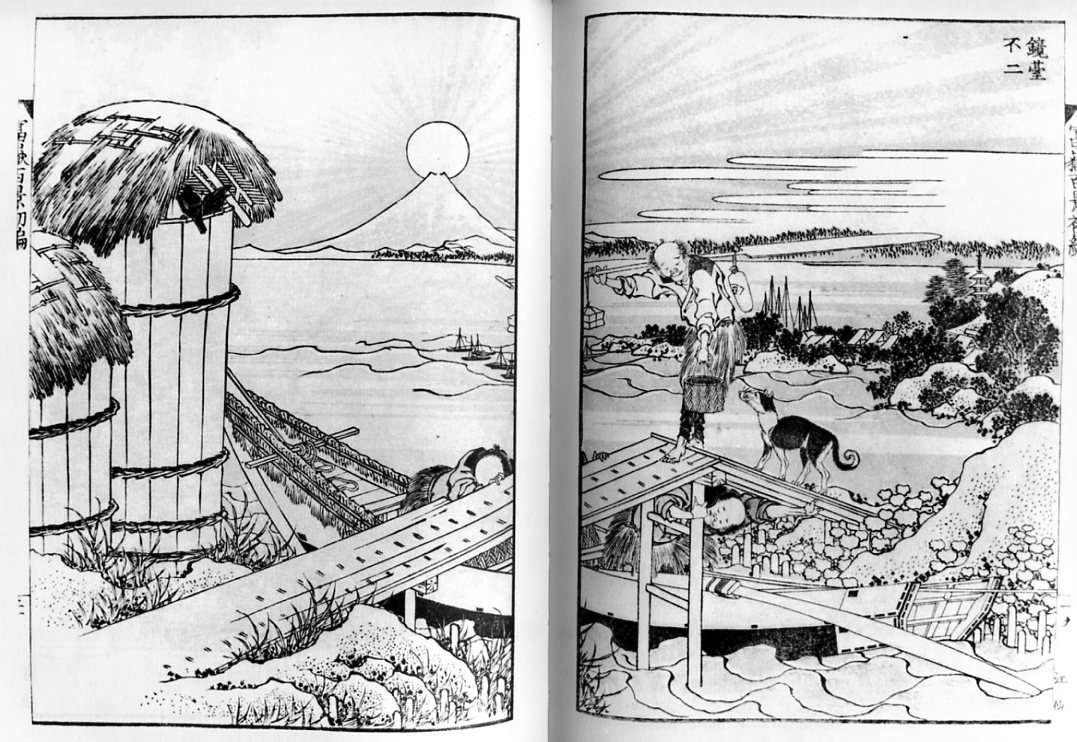

This is one of Hokusai’s One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji. It’s title of this particular plate is “Fuji as a Mirror Stand.” The point, or meaning, is, then, a kind of visual pun — the image of Fuji in the background with the sun sitting on top of it recalls a mirror sitting on its base.

If that image is what the print is about, though, what to make of all that action in the foreground? The man with his dog crossing over the bridge can be seen as a visual mirror of the mirror, perhaps — but Hokusai makes it very difficult to see the action there as pure formal doubling. Instead, we want to see it as narrative. What (we ask with the dog) does he have in that bucket? Where is he going, and where are those boatmen going under the bridge? Will they speak to each other? Do they see each other? What’s their story?

In this case, we might say that the narrative, or the demand of narrative, acts as an excess; an addition balancing on top of the mountain. Human stories pass over and pull under the image; what you see is disturbed by the demands of what happens. You can look for your reflection in the serene and distant mountain, and you may even see it, but your dog is still beside you, excessively nuzzling, demanding that you move on.

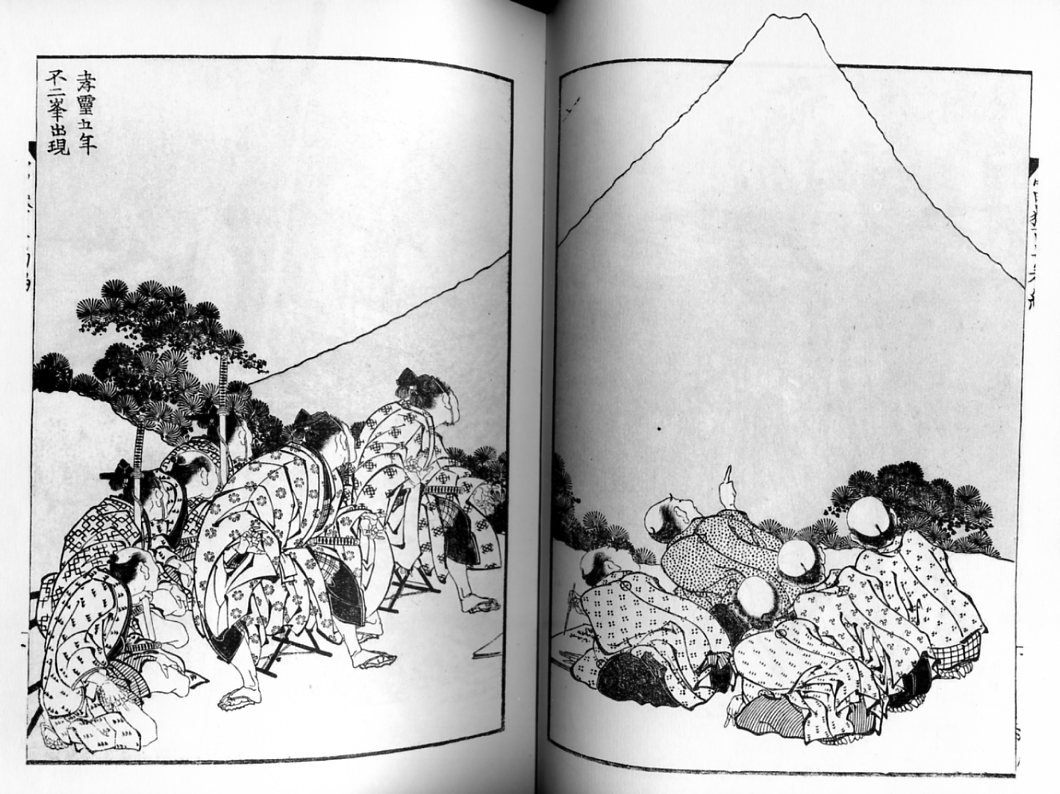

Here’s another view from the same series which works in somewhat similar ways.

The title is “The Appearance of Mt. Fuji in the Fifth Year of Korei.” It is supposed to show the actual date of the appearance of the mountain. Befitting such a momentous occasion, the figures gathered here are intently focused on Fuji. On the left, government officials stare, their attention riveted — so much so that their hands imitate the curve of the mountain’s top. On the right, a group of villagers gaze with similar single-mindedness…for the most part.

There is one exception though. A single villager has been distracted; he points off to the side at…what? A bird? Falling bird poop? Godzilla?

You could easily read this as in line with the last image. The meaning of the drawing — its purpose and point — is the view of the mountain itself as miraculous and devotional presence. But there’s a story in excess of that image; something has happened, and though we don’t know what it is, it draws us away from the image and on to the next panel, even though, in comic-book terms, there isn’t one.

But while you could read this as narrative excess over the meaning of the image, you could also read it as image excess over the meaning of narrative. The scribe next to the pointing man has been recording the story of the mountain on the day of its new creation. But he is distracted by sight — first of the pointing finger, and then, presumably, of whatever it is over there that we can’t see. For us, the hint of a story is a distraction from the view. But for the writer in the image, the hint of a view is a distraction from the story.

Of course, outside the print, there isn’t really a view or a story — just a mystery waiting to be charged with meaning. Narrative and image both leap at the chance, climbing one on the other, each over each, like Mt. Fuji rising through Hokusai’s frame.

Aren’t a lot of those Daredevil circles and semi-circles diagetic, though?

Yeah; Andrei mentions that. The point is that they’re formal unifying role exceeds their simple diagetic purpose. Daredevil’s sonar always is drawn as circles, but it’s unusual for the circles to become as insistent a formal element as they are here.

diegetic

I would like to think I more or less completely bastardized Peanuts (my all-time favorite comic strip)by removing the words. It’s essentially a linear theater strip with inflexibly recurring symbols, and I made it into a big mandala orgy barf. Whether that’s god or bad, it certainly wouldn’t endear me to Chris Ware, even though it could be construed as his fault that I made those.

“their blank, stunned, failed efforts at speech only emphasize their tortured transformation. ”

Charlie Brown looks kind of happy to me in the second picture.

He does. I think it’s false consciousness.

I mean, if I can at the very least unleash the secret semiotic jouissance of Charles Schulz, my efforts has not been in vain.

Scuse mine grammar.

I kind of fail to see how the Hokusai images call into question my “conception of the visual as excess.” It was in no way supposed to be a general notion, just a quality noticeable in specific works where such excess really does exist. I would not claim that of the Hokusais, where the so-called “excess” is easily understood in very different terms (as stage business, as a Barthesian “effect of the real”), etc.

Also, I never say “illustration is excess.” I mean the “logic of illustration” to denote the demand (in comics) that the images illustrate the text and nothing more. It is that meaning which I claim is exceeded by the visual. Of course, the visual can be its own meaning–as in, well, abstract comics! Or, for that matter, in most Fort Thunder stuff, etc. But I was referring to that specific ideology in comics, which is widespread, and to which I usually associate the even more reductive ideology of “cartoonism” (see McCloud, Ware, Brunetti, etc etc), by analogy with “rockism,” a belief that the only “proper” comics function with the iconic reduction of the cartoons, and a consequent relegation of comics that do not employ cartooning–such as, say, Hal Foster, or for that matter fumetti–to a lower rung of quality. And as “rockism” does employ a notion of authenticity, I think there is a reference to authenticity, of a sort, in cartoonism, too.

Thinking more about this: cartoonism, well, is exemplified by the Matt and Brubaker quotes. It implies an economy of the image in the service of the intended verbalizable meaning, or script, where anything superfluous is to be discarded. So from a strict “cartoonist” perspective, even Hal Foster, not to mention photographs, would constitute that kind of “excess.” I think one can construct a “logic of illustration” that is perfectly ok with Foster, so I guess said logic is wider, more accommodating than “cartoonism” proper.

“just a quality noticeable in specific works where such excess really does exist”

I guess it’s unclear to me that this is the case, exactly. If you’re saying there’s an excess beyond meaning, I don’t see that as true (since there are other kinds of meaning besides narrative, as you also note.) If you say excess beyond narrative meaning, then that seems to be the case in all kinds of work, including Hokusai.

I see your point about the cartoonism…but that’s saying that from that perspective, there’s an excess, not that there is an excess that’s really there outside of the framing of cartoonism, right? That is, the excess isn’t in the Miller pages or as a quality of the Miller pages, but is rather only excess from the perspective of someone who would insist that those pages be evaluated according to whether or not they illustrate the script.

Anyway…I think your idea of excess to characterize the relationship between the visual and the narrative is provocative in a lot of ways, exceeding (if you will) the debate about cartoon ideology.

Well, I also don’t think you can bring Hokusai in here because I was discussing specifically comics–an ideology within the comics field. And, yes, you need to discuss intention, the framing of the work within the institutions that produce it, distribute it and promote it, etc. No kind of meaning whatsoever exists in any work outside of such structures. But these structures tend to restrict–or direct–the understanding of meaning, and in some works that restricted meaning is exceeded. And again, I said specifically what “meaning” I was referring to. I think the Hokusai meaning can’t be read according to comics reading protocols. Within its own structures of comprehension, the excess isn’t there. (Which is not to say it’s not fascinating, great, etc.–and, by the way, thanksfor scooping me! :) )

You’re not scooped! Surely there’s enough excess in Hokusai to allow for more than one (or ten!) post(s).

I would agree that meaning only exists in contexts…but I think those contexts are more variable and subject to more interpretations than you seem to (at least here.)

For example, I think there are a lot of interesting connections between Japanese print series and comics, and while one can’t be read as the other, I don’t see any reason that ideas generated by one can’t be cross-applied. Similarly, I think that Hokusai is very much playing with, or thinking about excess. The mountain goes through the frame, the finger points off panel, the views go to 102 rather than 100… And, indeed, throughout the series, you can often read the mountain as an excess on the scene, or the scene as an excess on the mountain.

Basically, I think in your original post, your thinking about ways in which image and text can be said to mean without reducing image to text. Charles H. uses the concept of tension, which implies a pulling back and forth. You use excess, which has more of a sense of vaulting over one another; not in stasis, but in overflow; not balanced unity, but off-balance plenitude. I think it’s a very nice concept, and one which seems like it can work in a lot of different contexts.

But the way you put it, Hokusai thematizes excess, which makes “excess” itself the meaning. Which is fine, but not the same thing I was talking about. I just don’t think that Hokusai had such a restrictive dominating ideology of meaning as comics do, so the “dialectic” (in parantheses because it’s not exactly that) doesn’t work quite the same way. And my upcoming piece is all about Japanese print series as comics, or as sequential art, at least–as you know since you’ve read it!

Thanks for the appreciation of the notion as I used it. I wouldn’t want to put it alongside Charles’s “tension,” though. I think his idea still very much fits within the “logic of illustration” (as he’ll readily admit). More importantly, perhaps, his is an ever-present notion, a kind of universal of the aesthetic of comics. I don’t think “excess” is quite that–I certainly wouldn’t want to use it that way.

“I certainly wouldn’t want to use it that way.”

But I might!

I realize that you weren’t making excess the meaning; that was me doing that. I think it works for Miller too, though.

I need to read your piece again now that I’ve seen the prints. I’m looking forward to doing that quite a bit, actually.

If creating and developing Charlie Brown as an original character is different from referring to Charlie Brown intentionally, is different than referring to him unintentionally, who decides where the continuity, the inflection, and the excess is happening? Is it really a matter of coding on the front end?

I think Andrei’s point is that you have to look at the context of the work and its creation to decide whether the visual is an excess on the narrative. He also seems to feel that that excess can’t be intentional or thematized(?) because then it’s not excess.

Which I don’t think I agree with. Meaning isn’t just coding on the front end, surely; it’s interpretation. And it seems a lot dicier to try to figure out what the front end coding of meaning is supposed to be (did Frank Miller think he was just serving the story? or was he deliberately riffing?) than it is to do a reading based on one’s own aesthetic experience. Of course, the lines get somewhat blurry, since one’s aesthetic experience tends to involve one’s sense of intentionality, and the author’s intentions surely affected the aesthetic experience.

It’s sort of funny that we’re talking about intentions abstractly, since you’re right here and you’re one of the artists I talked about!

Lotta interesting stuff here, but this bit is a mind-bender:

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…There is one exception though. A single villager has been distracted; he points off to the side at…what? A bird? Falling bird poop? Godzilla?

…the finger points off panel…

————————-

Just because he’s not pointing to the exact center of the mountain, doesn’t mean he’s not pointing to the mountain at all:

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/Hokusaipointer.jpg

As for that “the finger points off panel” assertion, you could as easily say that everybody in the picture is looking off-panel, too. They might all be looking in the general direction of Mount Fuji, but their eyes could actually be focused on some fascinating object that the artist did not deem worthy of inclusion.

The thing is, would that make any sense?

As long as I’m picking nits here:

————————–

…as you’ve probably noticed, there are no words. When it came down to it, Bert decided that the pictures looked better without the text. So he took them out.

In some versions of comicdom, this could be seen as a cardinal sin. As Joe Matt says, ”I’ve gotta draw minimally to serve the storytelling! The writing always comes before the art!” Similarly, Ed Brubaker argues “I’ve always felt that the writing was far more important than the artwork… As long as the art supports the story…” It’s hard to see how Bert could have more thoroughly violated these precepts.Not only does his art not serve the storytelling, but in the name of the art, he actually went ahead and removed the words altogether!

Of course, in our project, the words were always subordinated to the drawing; Bert did the artwork first, then I provided words…and then he decided the words didn’t fit (in some cases literally — too much text for the boxes.) But that merely underlines the point that art here was not subordinated to storytelling.

—————————

Uh, the elimination of dialogue, or text-panel verbiage, doesn’t mean that narrative/storytelling no longer exist.

Bert Stabler may not have written up a script with lines such as “Snoopy wearing a KKK hood looks up at Charlie Brown, who’s got a Snoopy mask on. Lots of spermatozoa branded with CB’s jagged-line shirt design fly away from him…”, but a narrative can clearly be inferred. For all their topsy-turviness, there are panel after panel with the same characters recurring in altered situations: a temporal dimension is obviously involved here.

—————————-

…Bert’s excision of text can also be seen as a kind of deliberate overtopping, or annihilation, of narrative content.

—————————-

If we white out the bombastic dialogue and captions in a Lee/Kirby Fantastic Four comic, does that mean the “narrative content” in the art pages for which Jack created a plot and drew up, is not there any more?

‘Nuff said…!

Well, I intentionally referred to Charlie Brown and the highly codified visuals as a launch point, which kind of operated like the empty word balloons– it was all just there to make the rest of what I was doing resemble coherence. It was sort of an overwrought automatic drawing exercise.

Noah: This is the real meaning of the 100 views (there’s no excess at all; I quote my blog): “Fugako hyakkei is a religious book. As Henry D. Smith put it in his great intro to One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji (George Braziller, 2001 [1988]: 7): “One Hundred Views of Mt. Fuji is a work of such unending visual delight that it is easy to overlook its underlying spiritual intent. Hokusai was, as he prefaced his signature, “Seventy-five Years of Age” when the first volume of the work appeared in 1834, and his effort to capture the great mountain from every angle, in every context, was in the deepest sense a prayer for the gift of immortality that lay hidden within the heart of the volcano. By showing life itself in all its shifting forms against the unchanging form of Fuji, with the vitality and wit that inform every page of the book, he sought not only to prolong his own life but in the end to gain admission to the realm of the Immortals.”

Yep, that’s the edition I have, I believe. I don’t agree that there’s no hint of excess there. It’s about eternal life after all; there’s not much more excessive or expansive than wishing for infinitely extended years.

I think that the contrast of visual and narrative is often used throughout the series in precisely that way; as a way to point towards a spiritual yearning and a hope for something beyond. The mountain as image looming over and outside the human activity; the human narrative which goes on around and beyond the looming mountain…and perhaps resolved in that final single line image, where the story (in this case, Hokusai’s act of drawing itself) and the mountain become one.

I’m reading this Agamben book, the Kingdom and the Glory, and he’s talking now about the how Western power, going back to the Roman Empire, can be seen to reside more in symbols than in laws– at one point he says that religion, art, and empire overlap each other “without remainder.” Which does get him back at the usual Marxist critique, the power critique of art– whereas Foucault would probably connect the art to forms and acts of speech, loosely construed, before connecting thoser to power.

Anyhow, it seems like once you have visuality as narrative extra, you can perhaps say the reverse– that all the Barthesy detours and Derridean contradictions perform something poetic and visual within a symbolic space. They serve each other– I don’t know that the excess is intentional or unintentional, but it is meaning, the anti-entropic, non-zero-sum aspect of aesthetic experiences.

I like that. Ideology as symbolic and aesthetic definitely makes sense to me.

Well, in my upcoming post(s) on 100 views, I address that quote–briefly put, it’s not quite as simple as that.

I think ideology and visuality do go together, in the “magic” sense that sits well with both politics and religion. But I think for the magic to be important, you need what I call “nonsense”– the gibberish element of the detours and contradictions and gesticulations constituting the chaos-void of the cosmic anus.

Sorry to go back a bit, but don’t you think there’s a distinction between Andrei’s “cartoonism” and the “logic of illustration”? I don’t see them as the same thing, even though they’re united against visual excess. In illustration, image serves the text. In cartoonism, image aspires to the quality of text – it’s supposed to supplant text, create an alternative writing.

I’m not so sure…as Andrei describes it, and as people like Joe Matt seem to be using it, there does seem to be a desire in cartoonism to have image serve the text, or be subordinate to the text.

The idea of image as alternate writing is actually kind of heterodox as far as the mainstream of U.S. cartooning goes. You can see Warren Craghead (playfully) aspiring to that here — but as Warren shows, it leads you someplace pretty different from illustration.

I suppose what I meant is, cartoonism holds that cartooning is a special combination of images and writing that constitutes its own language, and that for this language to succeed, visual excess must be avoided. I’m looking at Ware’s introduction to his McSweeneys edition and he’s keen to downplay the importance of elaborate or even good drawing: “the more detailed and refined a cartoon, the less it seems to ‘work'”. But I still suspect he’d disagree with that quote from Matt because he never says that the image is subordinate to the writing: they’re both equally subordinate to narrative.

I agree with Paul about cartoonism, but in this case (referring specifically to comics, not to illustration in general), by “logic of illustration” I didn’t mean that the image had to be subservient to the actual text–I misspoke, or mis-wrote, above–but to the narrative meaning, which is somewhat different. Here is what I wrote in the post to which Noah links:

“Let me be clear. It’s not a matter simply of words versus art. Rather–well, here’s how Joe Matt (in the example I illustrated in the Ditko post) puts it: “I’ve gotta draw minimally to serve the storytelling! The writing always comes before the art!” It’s the storytelling that’s important. Think of it as script plus art in its minimal, purely representative mode. But the art must not exceed that mode. It cannot take over.”

And, by the way, I really like that you guys are using the term “cartoonism.” I hope it takes off!

I like the Noah/Bert collaboration, and agree that in comics, text and art equally serve the narrative.

What the hell–here are some more formal definitions:

Cartoonism, n. By analogy with “rockism,” a belief that the only “proper” comics are those that employ the iconic reduction of the cartoon, and a consequent relegation of comics that do not employ cartooning–such as Hal Foster’s “Prince Valiant” or fumetti–to a lower rung of aesthetic quality. Prominent proponents of cartoonism include Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti. Scott McCloud’s discussion of cartooning in “Understanding Comics,” chapter 2, can be seen as the main theory behind cartoonism.

Logic of illustration: in comics, the belief that the subject matter or narrative is dominant and that a comic best succeeds when the art is fully deployed to convey, in the most powerful or subtlest ways possible, the intended meanings and themes of that subject matter. In the ideal situation proposed by the logic of illustration, every choice of graphic style and of visual-narrative treatment can be explained through its function of conveying or amplifying the narrative meaning and its wider thematic connotations; no such choice can be left unmotivated or explained through aberrant motives that do not pertain to said subject matter. The logic of illustration, which implies the belief that comics is (principally or exclusively) a narrative art, is the ideological basis behind most current practices of the formal criticism of comics.

Oh, and Noah–I just saw your comment on that post. Here is the other post you want to read: http://abstractcomics.blogspot.com/2010/01/more-on-ditko-and-abstraction.html

–together with the Frank Miller one you took all those pictures above from. And of course, my “Holy Terror” one also relates to these issues.

Add to definition of “cartoonism”: “a more restrictive form of the logic of illustration”

Add to definition of “logic of illustration”: “a form of logocentrism (q.v.)”

Last comment for now, I promise! I just looked up “rockism” (I was using it the way I remembered it from the ’90s)–but it’s amazing how much of it applies, with barely the tiniest tweak:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rockism

I think Andrei should define more things. I like those kinds of formal definitions.

I’m having trouble with the logic of illustration as a form of logocentrism though. Not because it can’t ever be, because sometimes it is, but I’m struggling with the whole notion of subordination as it’s articulated here, I think; there’s a sort of wickedness to narrative as you talk about it that’s incredibly — and unnaturally — limiting, because it’s a demand rather than a desire.

If you shift from demand to desire, the logic of illustration, the hailing cry of narrative, are forms of logophilia … they’re not aggressive or wicked or laden with value judgement and power plays. I think to me a “logic” — of illustration, of comics, of whatever — is always a mode of jouissance, never a “belief”. The beliefs, the power — those are political dynamics. They are not the fault of the “logos” part any more than they’re the fault of the “imagos” part — they are the fault of the “centrism” part. The antidote to logocentrism isn’t, well, imagocentrism — it’s peripheralism. (In poststructuralism, the peripheralism of structural causality.) Imagocentrism creates a false opposition. You don’t… destroy the logos and replace it with the imagos; you decenter both.

One of the great limitations of much comics storytelling, for me, is the failure to explore the deeper nuances and logics of how the images create the narrative, even in logocentric narrative. They don’t just “serve” it, not even in illustration. Not everything happens at that absolute horizon of epistemology. Just like metafiction is self-consciously attentive to how words make narrative, comics could be so much more attentive to how images make narrative — how images become logos. That awareness of becoming would be an important part of logophilic comics to me — and I definitely desire them. But they’re so rare, and I think that’s because most people grab so tightly onto this opposition between logocentric and imagocentric and ignore the possibilities of, well, ahem, peri-philia.

I think Hokusai is pretty on top of that. The 100 views is nothing if not aware of peripheries.

Caro! You should limit your responses to one forum or another… I just got done answering you on Facebook (on the same subject!) and now I have to address it all again here? I’m exhausted.

I see that I’ve already answered (I think to your satisfaction?) your first three paragraphs, because they are largely what you wrote on FB. (But just to be cranky, I’m not going to quote that here! So there. If y’all want to read them, look them up on my Facebook page–or friend me, if you haven’t done so already.)

As for the last paragraph, I think it largely comes from your misprision of my definition as a logocentrism/imagocentrism opposition (which I explained was not the case)–which you then re-cast in the form of the dichotomy you always discuss, between comics as literature and comics as art. As I’ve said before (and I don’t feel like rehearsing that argument here), I find that dichotomy too simple–and in any case, that’s not what I was talking about here.

And yeah, Hokusai… I do talk about that decentering, at length… it’s coming… soon…

“the deeper nuances and logics of how the images create the narrative, even in logocentric narrative. They don’t just “serve” it, not even in illustration. Not everything happens at that absolute horizon of epistemology. Just like metafiction is self-consciously attentive to how words make narrative, comics could be so much more attentive to how images make narrative — how images become logos. That awareness of becoming would be an important part of logophilic comics to me — and I definitely desire them. But they’re so rare”

Actually, I don’t think they’re so rare–but what you need, perhaps, is more of a kind of criticism that draws out how this happens, how images become narrative… Maybe I’m delusional, but (as I’ve said elsewhere) my teaching is much more indebted to the logic of illustration than my critical writing (which sets itself up, for various reasons, more in opposition to it), and I think that if you took one of my classes, say, you would see how I attempt to wrestle with exactly that notion, of the complex narrativity of images. It might satisfy you–or maybe not.

Yeah, sorry — I didn’t catch it was here! Stupid newsfeed only gave me the later post…

Sorry for my crankiness. I truly am exhausted. A total of 11 or 12 hours of sleep over the last three nights. And it’s late and I yet have to go to sleep tonight…

I think part of the aesthetic issue for me is that those comics (in the narrow sense rather than the big sense that includes Hokusai) which are attentive to the narrativity of images don’t often aim for logophilic narrative — the pleasures are kept quite discrete, and there’s a strong sense of medium-specificity, this idea that images have their own unique narrativity that is distinct in kind from the narrativity of the logos. That’s there, a little, in your phrasing “the narrativity of images,” as if it is a specific narrativity (“the”), belonging to the image (“of”).

Contrast, perhaps, with “narrativity from images” — which suggests a broader narrativity that is in the process of becoming, not in the state of being possessed; an epiphenomenon rather than an attribute; structural causality rather than logical or mechanical causality.

I do think it’s to some extent just a matter of emphasis (as with the opposition: my sense that you were opposing imagocentric to logocentric mostly went away with a minor rephrasing to get rid of the value judgement words) — but it’s both the emphasis of the work and the emphasis of criticism/theory. But those subtleties of emphasis are a meaningful part of logos.

I didn’t think you were cranky…go sleep!

Caro–you are making too much of my words (this is what drives me crazy about HU and about debating with you, often…) The implication you draw from my “narrativity of images” is not there–and “narrativity from images” is kind of tortured English, seemingly to draw an opposition that doesn’t really exist… My phrasing was trying to be nothing by a rephrasing of how you put it yourself: “the deeper nuances and logics of how the images create the narrative… comics could be so much more attentive to how images make narrative.” “Images make” “Images create”–if I had written those phrases, you could (would) have equally criticized them, just as you criticized my “of.” But there are many kinds of “of” that are not the “of” of belonging. Again, I feel you are re-casting my words according to a dichotomy, that is a very strong preoccupation of yours, that I don’t fully subscribe to, and that they were not meant to fit. It was an honest attempt to restate, in my response, the concern of your question. If you’re going to pick on *that* as one of your pieces of evidence–well, in that case I despair of a constructive result ever coming from such a discussion–both because it does not seem to me to be constructive, but also because it slows down and delays discussion to such an extent that such a result can never arrive.

Said in all friendliness…

Cartoonism is an excellent and necessary coinage. But what do you call its adherents? Cartoonists?

I suppose I need to go away and get my head around what excess is. I struggle with it, because to me all that detail in Prince Valiant is anything but excessive, and it’s not separate to the narrative. It’s saying: this is what it looks and feels like to be in this world I’ve made in which this story I’m telling is happening, and without which you wouldn’t fully understand my story. And I think Jimmy Corrigan actually has a lot of that too, on top of which, it also has a layer of excess that’s saying: I’ve got rid of a whole load of unnecessary junk here. Which I would argue is also the case in, for example, Hemingway or Mies van der Rohe.

But I’ve got a horrible feeling I’m still missing the point about what everyone is meaning by excess …

I like your formulation Paul. I think an excessive lack of excess if central to a lot of comics, including Peanuts and Chris Ware.

An aestheticized, excessive display of the glory of brutal efficiency links Bauhaus, Philip Johnson, and Nazis pretty, well, effectively.

But then taking this to the place of “oh, never mind the bollocks, here’s an infinite grid of pleasure options” really ends up serving rather than opposing this kind of vacuum-philia.

Sorry, but I’m reading Agamben, and it keeps being an experience of “oh yeah, everything is about power/the Holocaust.”

Cf. the later diffident, peripatetic work of Philip Johnson…

I am currently enduring yet another radio payola play of Bon Jovi’s “Dead or Alive,” which is one of the most transparently semiotic songs about capitalism I’ve ever heard. Alienation, reification, evacuation– and country-glam-Morricone musical details only reinforce those elements. It’s really hard to say if it’s entirely unintentional… I think what makes it a bad song is how transparent it is, though, whereas the subtletyof what it’s saying slightly redeems it. But only because it’s Bon Jovi– if it was Joy Division, it would just be angst, and so I think the nonsense element makes it somewhat tolerable.

But is the new Van Halen album any good?

Andrei … I mean … I’m saying comics aren’t logophilic enough (although I wasn’t really saying it about you personally) and you’re saying I’m paying too much attention to words. Um…

Let me just try again. I do want theory (not just criticism) that articulates how images become narrative, but I also want it to track a greater distance away from the epistemological limit, and I don’t think the work is there to use as a foundation.

Your work grapples with narrative close to that limit, specifically because it’s abstract. Fascinating, important, theoretically essential — but not really logophilic. From the perspective of logos, abstraction itself is always at the limit. The moment of movement from “abstract” to “representative” that’s so central to abstract comics’ engagement with narrative isn’t one that makes sense in what we normally think of as logos, because the logos is always simultaneously fully abstract and fully representational. It isn’t really the logos until it moves out of that moment where abstraction and representation are differentiated — that’s why the Imaginary and Symbolic are differentiated, why Saussure is so vital to poststructuralism. You can reject Lacan, but you’re going to have an awfully hard time saying that even the most ambitious literary fiction is non-representational, let alone storytelling or genre fiction…

Abstract Comics are powerful, to me, at the limit, because they open up a aspect of narrative that is extremely hard to see from the perspective of linguistic analysis. They are not inherently imagocentric. But that aspect only really obtains in logos narrative at the limit, at that deep structure level close to the horizon of epistemology, and the distance from representational content in abstract comics alone pulls them away from grappling with logophilic narrative as it is experienced. What happens at the limit is fascinating — which is why this isn’t a criticism — but as I said earlier, not everything happens at the horizon of epistemology. Most narrative does not. “Great storytelling” never does, for reasons that should be obvious…

And comics, IMO, don’t have a lot of great storytelling. I don’t care how much semiotic content Chris Ware thinks he’s packing into his little boxes — he’s both less narratively complex and more narratively dull than pretty much any writer in any volume of the Norton Anthology of anything. And almost all comics that are narratively complex and ambitious foreground abstraction in some way, which distances them from logophilic narrative which is always representational.

So maybe you are asserting, counter to all this, that Abstract Comics actually are narrative in the same way that, say, Gravity’s Rainbow or Barth’s Chimera or Woolf’s Orlando or even Bronte’s Wuthering Heights are? But I really don’t see that, so if that’s the case then that’s criticism I absolutely DEFINITELY want to see.

Bert – the walls of my office have 42″ high photographs of the ruins of Philip Johnson’s Tent of Tomorrow.

Noah, IRON MAIDEN.

Chris Ware was cool before he went all revisionist. The old Big Tex and Sparky comics from the ’90s are what made me interested in comics in my 20s.

Please, let’s not mention Van Hagar, for any reason ever.

The new album has David Lee Roth back! I’ve heard decent things about it, but I am frightened….

Caro, I’d disagree that there aren’t comics which are narratively complex compared to literature. Have you read Watchmen? It’s a puzzle-box of a book, and a lot more narratively interesting, to me, than something like Delany’s Nova, which is mostly just space opera with some program fiction thrown in and then mixed up with obvious pomo tics. It’s certainly more distanced from its narrative than Watchmen…but that just works as an excuse to disavow its investment and be generally half-assed.

Some of Chris Ware’s stories are really narratively complex as well; like this one, for example.

Both Watchmen and that Jimmy Corrigan story do really interesting things with their use of images as narrative too, I think — they’re both definitely logophiliac and committed to images as part of that logoophilia.

I’d agree that it’s maybe not all that common — Asterios Polyp is something of a dud in this regard, and I think the Hernandez Bros. are as well. But they’re still not worse than a lot of literary fiction, which really can be a wasteland….

Well, “a lot” and “almost all” and “rare” seem like qualifications — is Watchmen the only example you can come up with? (I always come up with Fate of the Artist, which applies here too…)

I doubt very seriously that you’d like postmodern literary narrative in comics any more than you like it in prose literature, but that’s a) a matter of aesthetics — the medium should still be able to produce work in that genre, and b) why I put in Bronte, because there’s not _a lot_ of great representational storytelling in comics either. It’s not common; it’s not the done thing, most people don’t aim for it or even really seem to understand it. I hear cartoonists talk about storytelling and they seem to think it’s entirely about character and emotional verisimilitude. But there’s a lot more going on in Bronte (or Austen or Dickens or Shaw or Nabokov or … take your pick) than character and verisimilitude. (Did you ever get around to reading The Artist of the Floating World?)

Comics has genre, and it has abstraction and the avant-garde. And then it has “Fate of the Artist” and Watchmen and maybe 2-3 more that basically just prove that the medium of comics _could_ make a contribution to the genre of literary fiction. But there is a strong bias against that genre: from fans of genre fiction it’s because the literary genre is “pretentious,” and from fans of art comics it’s because the genre is “logocentric.” And the people who are fans of literary fiction and don’t hold either of those biases tend to hold up the Hernandez Bros. and Maus as what literary people interested in comics should like. To which I say, that is not logophilic narrative, and medium-specificity doesn’t constitute a free pass.

Well, I mentioned Ware as well. I’d probably throw in Lilli Carre’s Lagoon and Edie Fake’s Gaylord Phoenix, both of which fuck with narrative, which I think is a good sign that they love it. I think Dan Clowes’ work qualifies too (though I don’t much like most of it for other reasons.) Grant Morrison as well, I’d say, though he’s very uneven and in general less interesting visually. I think Peanuts also does really interesting things with narrative and image that’s definitely logophiliac.

And Ariel Schrag, counts I think. I could probably come up with more.

I’m confused as to why Gilbert and Maus don’t count. I don’t like either of them at all, but my problems with them are not that they’re not sufficiently literary or narrative. Maus is definitely very aware of narrative devices and of the kind of pomo issues that are important in a lot of literary fiction — problems around representation and reality, questions about storytelling, etc. etc. Why don’t you feel it’s logophiliac exactly?

And hey, I like lots of post modernism. Borges, PKD, Quentin Tarantino, Nabokov — all favorites.

Now I’m wondering what you’d think of Cerebus…

Noah – let me bracket work that’s appropriate for children for a minute here and talk about work that’s really only for adults:

Questions about storytelling and representation and all those things are literary themes. But literary narrative is also a lot about the manipulation of device. Device is higher level than prosecraft, and lower level than theme. Maus fails at the level of the sophistication of its devices. It relies too heavily on symbolism, and straight symbolism in literature is less sophisticated than the more elaborate deployment of metaphor or metonymy. This is why so many literary people sneer at it getting the Pulitzer: it’s a good instance of “medium-specificity constituting a free pass.”

Symbolism is a component of metaphor one some level, but literary metaphor is bidirectional whereas symbols are unidirectional. The technical definition of a symbol is something like “using a concrete object to represent an abstract idea,” although the “concrete object” can be a “figure of speech.” (Notice the visual reference there to “figure” — in pure prose, a symbol is metaphorically concrete, but it still has to be concrete to qualify as a symbol.) But in literary metaphor the concrete drops away; instead you are juxtaposing two — preferably more — relatively ungrounded and fluid abstractions and having them structure each other.

(It’s also important to guard against the metaphor itself then functioning as a symbol; it needs to be integrated back into the narrative in some way, so that the metaphor illuminates character or theme or casts the plot in a different light, etc.)

This all happens very self-consciously in postmodern fiction, which calls attention to these things happening and generally integrates a self-consciousness about device into the theme, so that device in some way is always referenced by the theme. However, with the exception of the self-conscious self-referentiality, it happens in non-pomo fiction too — in Shakespeare, in Shaw, in Austen, in every literary writer. To get to something that uses symbols as directly as Maus you have to go back to the great Renaissance allegories — and they are so much more elaborate in the sheer quantity of symbols. There’s no puzzle to Maus — and Watchmen isn’t nearly as puzzling as The Fairie Queen.

So the more you’re able to connect a myriad of abstractions to each other and to the devices used to build the narrative, the more literary the work is is. If there aren’t multiple abstractions interacting independently of whatever is happening concretely (so abstractions that are not symbols) and working in the service of the theme, the work is not literary.

Ware’s pretty explicit about his imagocentrism and his concern with the materiality of the page. But images are definitionally concrete. What happens when you’re imagocentric and concerned with the materiality of the page is you elide this layer of device and have a closer interweave between the concrete materiality and the highest abstractions of theme. This is a medium-specific property of comics — indeed of visual art — that makes it more difficult to build “literary” — or logophilic — narratives.

Even visual abstraction is concrete in the sense I’m using the word here, because it is working at that epistemological limit where the distinction “abstract/concrete” that is so native to, even constitutive of, the logos breaks down and you are faced with the material, visual word, evacuated of meaning. This is why the Imaginary and Symbolic are so named: the shift from the image-world, where the abstract is concrete, to the symbolic where they’re separated so that the concrete can be made to represent the abstract — that is the emergence of the logos (or in poststructural-ese, the founding gesture of differance).

Ware and Gilbert and to a lesser extent Clowes are all overtly concerned with the visual aspects of representation — it’s extremely hard to be a cartoonist and not be. This does not make them bad; this is not a criticism. It doesn’t even entirely exclude them from being thought of as a graphic mode of “literature”. But it does make them significantly less logophilic. Eddie Campbell might honestly be the only person working in a narrative mode in English who doesn’t fall victim to this — and an awful lot of people will derogate him by saying his work is either “mere illustration” or too verbose/literary. But he really seems to understand what’s missing, what’s different.

And, you know, honestly, on a much, much less sophisticated and theoretical plane, the actual prose that there is in American comics generally just blows. It’s ugly and colloquial and the writers apparently have the vocabulary of an average high-schooler. Regardless of how much prose you include in a comic, every single word of the prose you include should be _amazing_ — or you should pay someone to write it for you. If you love words, you put in great words. Period.

Illustrated children’s books, including but not limited to comics that include children in their readership, tend to be BRILLIANT at that, actually. But it’s really easier in children’s books, because the ideas are simpler, because there are less moving pieces — you can work with one device at a time rather than having to make the prose engage multiple devices simultaneously as well as multiple themes.

Caro: “Andrei … I mean … I’m saying comics aren’t logophilic enough (although I wasn’t really saying it about you personally) and you’re saying I’m paying too much attention to words. Um…”

Wow. That’s a cheap shot.

Nothing I said here had to do with abstract comics specifically, quite the contrary. Construing my words–or my critical work in general–to be specifically about abstract comics, and then arguing on that basis, is kind of refusing the dialogue, isn’t it?

Ah…okay, I remember you talking about this before. The problem with Maus is that the jews=mice is kind of dumb and simplistic, and the fact that he’s self-referential about it doesn’t ever really get past the initial dunderheadedness. I can agree to that (though others won’t, obviously.)

A contrast might be Kafka’s Mouse Singer, where the exact terms of the analogy between people and mice are a lot less stable. The mice are people, but they’re also still mice; the singer is like a human artist, but also not; which is then folded back to rhyme with the artistic process of the story itself. All of which is a lot more deft than having spiegelman in a mouse mask sitting on a pile of corpses and whining because too many people bought his book (though I guess the counterargument might be that the holocaust is itself blunt and should be treated so rather than more ambiguously, poetically.)

I think that Ware story I pointed to *is* a lot like Kafka, though…and the way he uses symbols in that story is very much in line with what you’re talking about. It’s very Freudian, but that only makes it more literary, not less, right? Superman is and is not his father; his Mom’s boyfriend is and is not his father; even the weird giant bird with its castrating beak is and is not his father. It’s a fever dream, but one that’s definitely logophiliac, and the concern with the visual aspects of representation really maps directly onto the way that dreams are both visual and sign (that’s not unlike how Lilli Carré’s stuff works too.) Nothing that happens in that Jimmy Corrigan story is concrete in any sense. It’s all a metaphor or a fable, again, like in Kafka. Over time Ware gets a lot more concerned about curtailing some of that in the name of cartoonism, but in that particular story,and in some of his other work, I really don’t see him as less narratively sophisticated than Borges, or Delany, or Barth, or whoever.

“Also, honestly, on a much less sophisticated plane, the actual prose that there is in American comics generally just blows. ”

Maybe more people need to be like Bert and just take the bad words out.

Paul: “cartoonismists”?

I wouldn’t claim at all that all the detail in Hal Foster is “excess.” I totally agree with you on this point.

“The question is the story itself, and whether or not it means something is not for the story to tell.”

Paul Auster, from his pretentious novel, pretentiously illustrated by Dave Mazzuchelli. Ugh. Certainly imagining itself as cinematic and stark, but just making me feel bored and creeped out by the nostalgifying romanticizing of white urban-ness.

I know I brought up Nazis as modernists, but I just really wonder what the impulse is to create literary comics if the images aren’ t super important. I mean, I kind of liked Bill Siencewicz’s Classics Illustrated adaptation of Moby Dick, and there’s always Watchmen– though the only reason that was a comic book was because it was about superheroes.

I guess I feel like there is a page-based narrative format for literary works, but not one for visual art, other than the comic book. So I find literary comics to be generally nostalgic in an icky way– they want to be film, but, like, more tactile.

Not to be needlessly provocative, but– why do we need literary comics? Chimps do not look good in tuxes.

Caro: while reading your comment my only thought was: Mattotti.

Noah: Let’s go back to Hokusai, shall we? You only have an excess of meaning after establishing what the meaning is, right? In the drawing above I don’t agree that the meaning is the, sorry for saying this, ridiculous: “[…] a kind of visual pun — the image of Fuji in the background with the sun sitting on top of it recalls a mirror sitting on its base.” The meaning of the whole book being religious (meaning: religare – to tie again) Hokusai’s meaning is all life forms around Mnt. Fuji. You can’t exceed everything. Also, here’s how Mitsugu Katayori explained: “The word manga in the phrase Hokusai Manga comes from the word manzen, which means browsing aimlessly. A long time ago, in China, there was a bird called Mangachuko. It had long legs and ate shellfish from the river. Hokusai imaged the bird when he named the collection of his drawings. He sketched as much scenery as possible, like this bird that picked up anything and everything, browsing in the river.” What’s the excess of “browsing aimlessly”?

I hope that you don’t think that meaning = narrative.

Oh and, by the way: here I used the mat concept of locus to describe Hokusai’s 100 views.

B~ert: “Not to be needlessly provocative, but– why do we need literary comics? Chimps do not look good in tuxes.”

Maybe you thought that you needed to be provocative? In that case what you wrote was not “needless.” Either way, it worked for me. I can’t remember anything about comics being more offensive, ever…

Sorry about the “B~ert.” My damn keyboard!

Domingos, I don’t think we’re disagreeing (or anyway, don’t think we have to disagree.) I don’t think there is only narrative meaning. But I do think that Hokusai uses different kinds of meaning and sets them against each other, more or less deliberately, in a way that is about, or means, or points to, ideas of excess.

Does that make sense? I’m using excess as a way to think about how narrative and image work together or against each other in creating meaning.

Now that I think about it…I may be disagreeing with you, because you’re pretty set against thinking in terms of image and narrative being separable, right? But I’m happy to agree to disagree; I don’t need my reading to be the only one or anything.

Andrei — I’d be talking about abstract comics and abstraction in comics here whether I was talking to you or somebody else, because abstraction is what’s at stake when explaining the limitations I experience with the image-narratives in most American comics and the frustrations I have with the generally derisive tone that inevitably comes out whenever anybody says “illustration.” I’m not making, as you claim in your initial comment, a simple distinction between “comics as literature and comics as art.” Honestly, the fact that there are visuals at all make it almost impossible for me to ever experience comics as literature, because visuals are concrete even when they’re abstract. It is only in the hands of someone like Eddie Campbell or Anke Feuchtenberger that comics become discernably literary to me — and Feuchtenberger collaborates with a writer. So that distinction would be so skewed toward “comics as art” as to be useless.

What I am saying is that the distinctions between literature and art — that is, logos and imagos, the signifier and the signified, and Symbolic and Imaginary, all of which are slightly different and increasingly less binary framings of the exact same distinction — will have to be taken on directly in any theory of comics narrative that I will find satisfying, because the status of narrative abstraction is altered by the presence of images. Literature and language have a native concept of abstraction that just doesn’t transfer unproblematically to situations of visual representation. Cross-application works best at that moment of differance, that interface between the Imaginary and the Symbolic, that Saussurean place where there is no distinction between the abstract and the concrete, only the unitary abstract/concrete and the representational. But once we move away from that really fundamental level, away from something like abstract comics, or other forms of avant-garde comics where there is a lot of visual abstraction in play, and toward something like Ware’s work, we immediately start banging up against the epistemology of the turn, especially its radical take on presence and absence — and everything becomes thoroughly saturated with the concrete and very removed from those things that characterize narrative in prose fiction. Maybe my longer response to Noah helps clear some of that up — that one talks about Ware and Maus as examples, but still discusses what I think are these largely disciplinary differences in the situation of abstraction. All visual representation, comics or otherwise, is in this situation vis-a-vis logos.

I don’t really see how my statement is a cheap shot — it seems to me to illustrate very aptly how much we’re talking past each other. I’m saying I don’t see a lot of sensitivity to words and language and the way narrative works in verbal contexts coming across in the way people make comics narratives and the way people talk about comics narratives — telling me to pay less attention to words is not a response to that!

Noah, I will look at the Ware story — I think I did the last time you brought it up but I don’t remember. I do tend to find Carre’s work to be fairly symbolic still, although I do like it, so perhaps that’s the example best taken on next…

I think the thing is — I don’t want to overstate this, but “symbol” is kind of a bad word in fiction. If there’s an honest-to-goodness symbol at all, anywhere in the work, it kind of tips those scales away from literature. Freud’s symbolic qualities are a big part of why literature so willingly abandoned him in favor of Lacan and Zizek et al et al et al.

What Dave Mazucchelli illustrated has absolutely nothing to do with what Paul Auster wrote.

Those would be cinematic comics. Literary comics are different. It would be incredibly incredibly hard to make Fate of the Artist into a film.

Because if you want narrative comics — which you don’t have to have, by any means, but going here on the assumption that comics overall does in fact want narrative comics — literature is exceptionally good at narrative and has a tremendously large and diverse body of narrative for creators of narrative to study and explore and be inspired by. And great artists pay attention to other artists who are great at things they want to do.

Caro–

I reject the insistence on applying a concrete/abstract binary to comics. With comics, the images are, in the strictest sense, concrete in terms of their meanings, but the meanings are not necessarily stable–they change depending on how they’re contextualized by the textual elements, the other images, and other aspects of the narrative. This is certainly the case with Black Hole or Jimmy Corrigan or Watchmen. If you want elaboration, please go back to my essay on Watchmen for the comics poll. I discuss how the meanings of the images change depending on the context, and how this is thematically in key with the work.

Noah: I didn’t think that you equate narrative and meaning, I was just checking… I don’t resist the idea of image and narrative being separable (I needed to forget more than a century of Modernism to think like that). Nope, if we are disagreeing is in one crucial question that wasn’t addressed until now in this thread: what is meaning? What I resist is the idea of asemy. Not that I deny it (again I needed to forget a few decades of Modernism in order to do that), but I certainly don’t think that Hokusai is it… quite the contrary: he’s so full of meaning that nothing can exceed it.

Caro: I see what you mean. Maybe Mattotti wasn’t such a good example after all (I need to go back to him and check). Old baroque allegories in the visual arts aren’t that liked (important, etc…) as all that either (with the possible exception of Tiepolo’s example, I guess…).

Caro, I don’t think that that Ware story is any more symbolic than any number of prose narratives. Like I said, Superman is and isn’t his father (and is and isn’t Superman, for that matter; there’s ambiguity even in the self-identity…which now that I think of it probably extends to Jimmy as well, who is and is not his self. Which is part of why it’s like Kafka.)

I have trouble believing you’ll like that Ware story, though. Part of what I enjoy so much about it is its violence (which is Freudian too, of course.) But I’ll be interested to hear what you think.

Robert — I don’t think it’s a binary. I say “visuals are concrete even when they’re abstract” … ? Isn’t that consistent with what you’re saying?

Ah…no, I agree with you Domingos. It’s only by separating different kinds of meaning that you get meaning in excess. It’s basically drawing a (somewhat arbitrary) circle around narrative meaning or iconic meaning that then allows you to having narrative meaning in excess of iconic meaning and vice versa. I think Hokusai is (arguably) playing with those distinctions and contrasts though.

Dalí is a Freudian painter who created great, enigmatic personal symbols. He should have stopped painting after the 30s though.

You know, I probably actually agree with Bert in the sense that I’d say most comics that people call “literary” really are cinematic and not literary at all.

I love Dali. But I wouldn’t call him literary. Maybe cinematic? Do people think he’s literary? I wouldn’t call Cocteau films literary either…

Caro–

I read that as referring to the work in Andrei’s anthology: “abstract” in the sense of “abstract art.” I didn’t read that as “concrete=literal” and “abstract=idea.” If I misunderstood I apologize.

For everyone else–

If you look at that panel I discuss in the poll essay, the concrete/literal is Veidt looking out the window while, in the foreground, a pile of randomly posed Ozymandias dolls is shown on his desk.

One abstract reading–my initial one–is that Veidt is pensive about the way he has chosen to live, and possibly waste, his life, with the dolls a reinforcing metaphor for his mixed feelings and doubt.

Another abstract reading–mine in the context of having read the entire book–is that Veidt is contemplating an unexpected problem, and the dolls are a trope for his distraction.

There is a concrete aspect, and there is an abstract aspect, but the meaning of the abstract depends on the context in which the reader sees the concrete.

For Caro and everyone else–

To a certain extent, I don’t define literary as “logophiliac.” I define literary as not wedded to concrete meaning in its presentation. It embraces the abstract; moreover, it embraces the mutability of the abstract. The more meanings a work can spin out of a signifier, the more impressed I am. And if it can wed that mutability to a larger coherent structure, the more likely I am to be blown away.

Noah: I see, thanks for clarifying your point. It seems to me that my mistake was to think in terms of a dichotomy: meaning / asemy (this was provoked by the music analogy, but I don’t think that music is asemic either; anyway…). You reading of the first Hokusai image reminded me of Umberto Eco’s essay about Superman. He talks about another dichotomy: mythical vs. prosaic time. That’s what Hokusai does above and you may bet that this is deliberate (the wood bridge – prosaic/functional mirrors – that’s right – the mountain mythical/sacred). I see no excess of meaning though, narrative or otherwise…

Another thing is this: how do you separate the “narrative” and the “iconic” in an image? Aren’t all images icons? Maybe we need to separate action/icons from static/icons?

Caro–I said it was a cheap shot because I didn’t say you you should “pay less attention” to my words, I said you were making too much of them–specifically, putting a reading on them that was not intended, a pre-fabricated reading that came from your previous preoccupations that led to a misreading of my sentences. If anything, you should have paid more attention to them, showed more sensitivity to how language actually functions: as I said, “there are many kinds of “of” other than the “of” of possession.” That you immediately jumped to such a stereotyped meaning seemed a too easy–cheap–maneuver to score a point.

Secondly: “What I am saying is that the distinctions between literature and art — that is, logos and imagos, the signifier and the signified, and Symbolic and Imaginary, all of which are slightly different and increasingly less binary framings of the exact same distinction — will have to be taken on directly in any theory of comics narrative that I will find satisfying…”

I don’t even know what to make of this! That you think the distinctions between literature and art in any possible way correspond to the distinctions between the further dichotomies you mention… That pretty much makes this entire discussion useless. Again (and again and again) I re-emphasize that I do not mean “logos” as speech, words, simply, but as “meaning.” Literature and art can be equally “logocentric,” while the imago, again, can appear in both. (The poetic image, anyone?) “signifier and signified”–are you kidding me? I simply can’t compute how while literature is on the side of the signifier, somehow art is on the side of the “signified.” If you truly believe that, it rather speaks to your inability to process comics in the literary mode in which you wish–and thus as a flaw in your perception, not in the object of your perception. Really, you should give up now, it’s hopeless. I mean, seriously–in what possible way is the distinction between the Symbolic and the Imaginary “a slightly different”–albeit “less binary”–“framing of the exact same distinction” as that between literature and art? The Symbolic and the Imaginary fully function inside both artforms: you might say that somehow language is symbolic (though the actual use of language cannot function without the imaginary, and the imaginary is fully at work in a literary text that implies a subject position, etc.), but art is fully pervaded by the Symbolic regime. There is such a complex overlapping and braiding between these various dichotomies that the slight out of “less binary” can’t even begin to cover the misunderstanding implicit in the statement that these all frame “the exact same distinction.”

Need I go on?

*Now* I’m cranky.

I’ve got a meeting at 7:30 sadly so I don’t have time to respond fairly until I’m back from that, but the poetic image is a metaphor, it’s not actually an image…

However, you are correct — I should have said “the distinctions that matter here between literature and art — that is, logos and imagos,” etc. I meant the “exact same” to refer to the pieces inside the dashes but that wasn’t clear. However, other than the editorial correction, you’re really just refusing to deal with Lacan again…I’ll come back to it after my meeting…

But you say “that is.” Id est. I.e. You are claiming that examples of the “distinctions that matters” between literature and art are those between logos and imagos, with that between signifier and signified, etc. It’s much more than a simple typo.

And in this case, quite the contrary, I do follow your Lacanian point, but I’d say only an over-simplified reading of Lacan would draw the equivalence between those distinctions as you draw it.

Anyway, don’t bother responding for my sake, I’m pretty sure we’ve reached a dead end here.

scratch “with that” in my first paragraph above.

I really dislike Dali, but not the way I dislike literary fiction. More the way I dislike television advertising.

Old television ads are cool!

Andrei…I don’t want to make things worse, and I’m afraid this might do that, and forgive me if so, but…you might maybe think about cooling down a little? I really don’t see anything in Caro’s comments that suggests she’s personally attacking you — the closest she came to a personal comment was suggesting that she thinks your comics are valuable, it seems like. I don’t know; maybe everyone could take a breath and have a relaxing weekend or something?

Domingos: “Another thing is this: how do you separate the “narrative” and the “iconic” in an image? Aren’t all images icons? Maybe we need to separate action/icons from static/icons?”

I’d agree it’s a rough distinction rather than some sort of seamless absolute category. I think in a lot of the Hokusai images there’s a gesture towards narrative (literally in the birth of mt. fuji image, perhaps). Hokusai asks you to imagine that you’re seeing a moment of a sequence, the middle of a story. In contrast to that (as an example) the mountain as mirror stand means in a way that is not (or at least less) narrative — it’s a chain of associations (the visual pun itself, the idea of individuals reflected in the mountain, the idea of all Japan reflected in the mountain, etc.)

Does that make sense? I’d agree that it could be interesting to think about the way images imply narrative themselves; it’s hard to draw a person without also drawing (or implying) that person’s story.

Anyone read Deleuze on the “time-image” and the “movement-image?” Comics actually mess with that in a nice way- especially if you imagine a comic book as a slide show with a soundtrack instead of a movie. The difference, excess, slippage, etc., in comics has a lot to do with time being flattened out and nullifed.

Let me just try restating the “equivalences” this way: imago lives in the structure relative to logos as the imaginary lives relative to the symbolic and as the signified lives relative to the signifier.

YES the relationship of the imaginary to the symbolic (et al.) is extremely complicated and overlapping. NO They’re not binaries (although imago and logos can be construed as a binary in a way that symbolic and imaginary can’t.) NO They are not synonyms. But YES they are structurally analogous, congruent.

It’s not an ontological equivalence, as you seem to think, Andrei: it’s an analogical equivalence. Imago, congruent with the Imaginary, is not the same as images in the Symbolic, but what is it that makes the difference? The status of abstraction, the relationship to semiotic meaning. That’s why I made the analogy with the emergence of the Signifier and the Symbolic, because the difference is a shift from something that does not have semiotic meaning, that is concrete, to something that does. Imago has meaning but it’s not semiotic. I’m happy to change that “exact same” phrasing so it doesn’t render you apoplectic, but I stand behind the claim of structural analogy, and the claim that structural analogy is important. There are two logics of the image here — not logic of illustration v. logic of comics, but a concrete logic and an abstract logic. As should be clear from the discussion about abstract/concrete and representationality, at the limit and away from it, it’s the structure that matters for my point — which you have clearly not understood (if you even read what I said about it).

Instead of “images make,” try Lacan’s “s’imageaillisse” — “springing forth from the image.” It may be tortured in English (although I don’t think it particularly is), but it’s got a pedigree. You’ll just have to tell me which meaning of “of” you meant to invoke, because honestly, I don’t see any meaning of “of” in English that would get me to “s’imageaillisse”.

But I think it’s more important that I said “that’s there, a little” — not “this is what you said or meant.” The sense of belonging is not foreclosed by your phrasing, the way it would have been had you used “from” instead. It is still a possible meaning, even though it’s not the one you meant. And that is, in fact, precisely how language works — the intent is not always obvious, people select from the interpretations that are left available to them, and sometimes the intent and the selection don’t match. “The letter always arrives at its destination.”

You misread the correction that I made a couple comments back. I didn’t say “the distinctions that matter between literature and art.” I said “the distinctions that matter here between literature and art.” Here, as in, “for the purposes of this discussion.” Not some overarching absolute claim about immutable differences between literature and art in all imaginable circumstances, but a specific distinction between them that is useful for explaining why Fate of the Artist is logophilic and Jimmy Corrigan isn’t.

Well, since Noah has asked, I was going to let it drop. But as you insist on continuing, fine, I will too.

Despite the “editorial correction,” at no point did you correct the phrase, “logos and imagos, the signifier and the signified, and Symbolic and Imaginary, all of which are slightly different and increasingly less binary framings of the exact same distinction.” Make it as much of a structural analogy as you wish, but “logos and imago,” for one, simply cannot be structurally analogous, no matter how much you twist them, to “signifier and signified”–whether in general, or for the localized purpose of distinguishing Eddie Campbell’s work from Chris Ware’s. Sorry, but attempting to draw such a “structural analogy” makes you sound theoretically clueless, at best.

“It is still a possible meaning, even though it’s not the one you meant. And that is, in fact, precisely how language works — the intent is not always obvious, people select from the interpretations that are left available to them, and sometimes the intent and the selection don’t match.”

So then–since most words are at least slightly polysemous, do you really think this is warranted in every situation? Really? That I can pick any of your words and, if in every instance you did not nail down the single, univocal meaning you intended, I,m allowed to pick on it as I wish, no matter the wider context of your statements, or even your later clarifications? If this is the case, what possibly gives you the right defend anything you yourself say?

I began by attempting a simple rephrasing of your statement, a restatement that was in no way adversarial. You chose to address an unintended meaning that you thought you found in my rephrasing to attack me by recasting, or intentionally misunderstanding, my point so as to make it fit a pet dichotomy you are obsessed with. When I protested that, you essentially invoked a complete relativism of language, which allows you to state anything you want and willfully misunderstand your opponent with no compunctions. At this point you are arguing in complete bad faith.

Noah: Did you ever read Dalí?

Domingos, I haven’t read Dali, alas.

“That I can pick any of your words and, if in every instance you did not nail down the single, univocal meaning you intended, I,m allowed to pick on it as I wish, no matter the wider context of your statements, or even your later clarifications? ”

This is how poststructural discussions work, usually, right? If Derrida doesn’t mean that you can push people’s words where they don’t want them to go, what does he mean? The “allowed to” seems weird — as does the accusation of bad faith. These are really abstruse issues; it seems like there should be a great deal of room to disagree without assuming animosity.