Click images to enlarge

Jaime Hernandez uses the temporal flexibility of the comics medium to work like memory: moments that are far separated in time recontextualize when put in proximity to each other. He shows that the ways people treat each other resonate unpredictably through their lives. In the world he has built on paper and in ours, passion can be fleeting, violence can happen in the blink of an eye and both can have long-lasting repercussions.

Hernandez’s recent comics show psychological insight and a command of expression and gesture that transcends his earlier efforts. As he refines the economic grace of his storytelling, he delves into the formative years of his characters to motivate them.

Secrets hinted at over the years are overtly revealed in Browntown, which is cut with flashbacks to a time when the teenaged Maggie’s family moves from Hoppers to Cadeeza to be closer to where her father Nacho works, so he can spend more than just alternate weekends with them. But, Nacho’s infidelity is revealed by his behavior at a party attended by both his wife and his young employee/mistress Miss Varga, who makes a point to cruelly inform Maggie of the disparaging nickname of her new neighborhood. Nacho thinks he has uncovered a betrayal when a drunken former workmate of his wife says he visited her house while they lived apart; here perhaps he displaces his own guilt to her and so to their daughter.

Maggie in her innocence percieves his half-serious disowning of her as only a joke and then does not understand her father’s violent reaction to her affectionate embrace. Now, on the one hand, he is freaking out because his wife and his girlfriend are both in that panel, a significance that Maggie and her mother are both unaware of. But also, possibly a baser sexual instinct provokes his panic; certainly Maggie could not imagine that he might be subject to arousal as a young girl climbs on his lap, even if she is his daughter. Perhaps, here is some of the rationale of misogynistic fundamentalism, men who repress women because of their own lack of self-control.

When Maggie later sees Nacho parked having an emotional scene with his lover, she places her as Miss Varga from the party and as the girl seen earlier leaving what she and his siblings had decided couldn’t be his car. The depth of her father’s betrayal destroys her trust, her idea of how the world is structured and when she then tells her mother what she saw, the family fully dissolves. Nacho won’t control himself and he isn’t protecting his family, which enables the ordeal that Maggie’s brother Calvin goes through and forces that little boy to take on the role of protector.

Left to his own devices and vulnerable, Calvin is initiated into a club of boys of varying ages that sit around in the grass with their pants down. Hernandez shows the boys mime heterosexual sex, though not engaging in actual sex. But, the older boy who leads this supposedly harmless homosocial group draws Calvin away from the rest to rape him repeatedly.

Hernandez shows the progression of abuse with understated taste in his increasingly appealing style, which makes it all the more horrific. The period shown is protracted, enough that both characters’ hair grows significantly longer. What is done to Calvin is long-term bullying and rape: he says “no” repeatedly, he expresses that it hurts again and again. The older kid threatens Calvin’s family several times when he tries to refuse to submit; his arm is twisted behind his back, he is forced. Ice pops are shoplifted and shared with Calvin as a show of exchange, which also makes him complicit in crime and solidifies the kid’s hold on him.

When the sociopath begins to spend time with Maggie, Calvin knows the boy’s practices and does not want him near his sister. He erupts and attacks the bigger kid for violating their pact: that if Calvin endures the abuse, his family will be safe. Calvin is badly beaten. When he gets home, there is a problem occurring involving Maggie that he doesn’t understand. Everything happens quickly; the family is breaking up, they are leaving town because of something unspoken, something bad that no one will tell such a young child. He mistakes the upset caused by Maggie’s exposure of her father’s cheating for something involving Maggie and his rapist. This is why Calvin does what he does, here and later in The Love Bunglers. His older, traumatized and disassociated self is still trying to protect Maggie.

A terrible irony of the revelations in these stories is that the reader knows much more than the characters do. As Calvin acts because he does not comprehend the true reason his family is falling apart, Maggie remains ignorant of what Calvin does out of love for her, she doesn’t realize who the older Calvin even is and eventually she denies her brother entirely.

__________________________________________

The first time I read The Love Bunglers, it unnerved me. A few days ago, I read it again and thought it was perfect. Still, I should restrain my interpretation until I see where Hernandez goes next, as I had to do with L&R NS #3, which is clarified by what transpires in the next issue. The scale of the lateral expanse he has developed makes it so he can continue to explore the spaces between and around what he has already established.

The most obviously outstanding aspect of Hernandez’s work is that his female characters are afforded, in their mesh of word and image, a depth of agency and complexity rivaled by no male cartoonist but Milton Caniff. It is hard not to single out Maggie for her particular charisma and I’m very impressed with Jaime’s most recent issue’s visual deglamorizing of such a beloved construct. His male characters are no less considered. Below, for example, Hernandez counterpoints Maggie’s subtle interaction with Ray by his frenzied coupling with “The Frogmouth,” a conflicted and sometimes tragic figure in her own right:

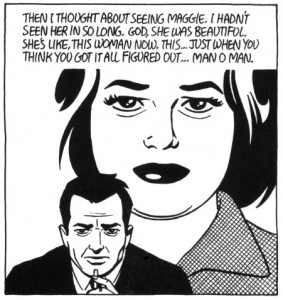

But it is Maggie who is imbedded in Ray’s consciousness; she’s unforgettable. Here’s one of my favorites of all of Jaime’s panels:

It reminds me a lot of one of my favorite Kirby panels since I was a kid, that I suspect Hernandez noticed as well:

Obviously such montages are well-worn romance comics devices, but Kirby was one of the initiators of the genre and Hernandez is one of his best students. In both stories these are significant moments in much larger, painstakingly set-up spreads of narrative; they are timed and emotionally keyed in the interaction of word and image so that the reader is driven to empathize with the characters’ yearning and to associate it with a similarly displaced attachment in their lives.

With Hernandez’s work, this identification goes well beyond sentimentality or nostalgia. I once sent him a letter that said, “Your work is great art because it is not only a pleasure to behold but also makes one consider one’s own experience with added perspective.” I can’t think of a better way to say that and it’s true, his work has given me many such moments of reflection. The director Jean Renoir wrote to François Truffaut, “It is very important for us men to know where we stand with women, and equally important for women to know where they stand with men. You help dissipate the fog that envelopes the essence of this question.” When I first read that quote, I thought of Jaime Hernandez.

________________________________________

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.

Hey James. Sorry it took me a bit to comment on this; I’ve got a horrible cold.

I’m still not sure that Calvin’s motivations are as clear as you’re making them out to be. I think it’s reasonable to think that something like jealousy is mixed in there as well in terms of his attack on Ray. And it seems needlessly complicated to assume that there’s some sort of pact involving his family — when he says, “you promised i’d be the only one,” it seems a lot simpler to assume that he’s talking about being the only one to have a sexual relationship with him.

I thought the way Jaime handled that part of Calvin’s story was nicely done, actually. Part of the rape is that Calvin has conflicted feelings about his rapist. If he could see what is being done to him as simply abuse, he might be able to get help.

That Kirby panel cracks me up.

I was trying to say as little as possible about L&R NS 4. But no, I don’t think Calvin is jealous of Ray regarding his sister, in his current state of breakdown he goes off when he thinks someone has hurt her. Simpler, nothing–I don’t see the ongoing rape as anything other than that, the kid explicitly threatens to do the same to Maggie and his other family members on the page above. And especially in the time depicted, I don’t think that Calvin would have felt able to expose homosexual bullying, for a variety of reasons.

Johnny Storm’s head is enormous.

“Hernandez’s recent comics show psychological insight and a command of expression and gesture that transcends his earlier effort”

I think that’s what was so successful about “The Education of Hopey Glass.” There was a richer interplay between the dialogue, characterizations and body/ facial gestures. They weren’t just complimentary to each other but almost fused. Wish I could be as positive about his more recent stories, but oh well.

Those stories are interesting–in an earlier draft, I mentioned the relationship between Hopey and Guy Goforth. But I dropped a lot of stuff to focus on Calvin and the scene of Maggie and her dad, because they are great work and because of comments elsewhere in the roundtable.

Great article James. I haven’t read the New Stories stuff, though this explains things pretty clearly. I also would say that given the time period when the “Browntown” story would have occurred, bullying and it’s impact wasn’t being addressed as seriously as it has been in the past few years. Much less the topic of male rape…could those factors play into why Calvin wouldn’t get help?

I reread “Browntown” this morning, and agree with James; I don’t think jealousy has anything to do with Calvin’s motivations.

I can see where Noah would get that idea; pedophiles often give their victims gifts, attention which busy or absent parents do not. Tell them they’re “special”; stuff which children yearning for parental love are desperate for. Thus in return, the abuser sometimes getting a kind of affection, even though their motivations were cynically vile.

However, after his being first invited into the “nasty in nature club,” offered a stolen popsicle, Calvin gets nothing positive from his abuser. In the various scenes — emotionally painful, for all their discretion — nowhere is there a hint that Calvin finds his being repeatedly raped in any way pleasurable; rather, always painful, humiliating. Something to be suffered through.

———————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

…it seems needlessly complicated to assume that there’s some sort of pact involving [Calvin’s] family — when he says, “you promised i’d be the only one,” it seems a lot simpler to assume that he’s talking about being the only one to have a sexual relationship with him.

———————————

Actually, that supports James’ argument. Calvin’s entire experience of sex is that it’s a brutal, degrading, painful experience. Therefore he doesn’t see his rapist’s interest in Maggie, his calling out to Calvin after having beaten him up, “See if I don’t cornhole [your mama] too!”, or his earlier threat, after Calvin said he didn’t want to do it any more, “What do you think if I did it to your sister or your whole fuckin’ pussyass family?” — which gets Calvin to submit, along with some actual arm-twisting — as exactly offering them sexual delights.

To Calvin, sex is nothing but a vile, cruel business; and when the threat of someone inflicting “sex” — as Calvin sees it to be — on his loved ones is made, he reacts violently, out of protectiveness.

Yes, Jenny, Calvin is left quite alone with no one to turn to for help. And thanks, Mike…I’m disturbed that so many here think that victims fall in love with their rapists.

“I’m disturbed that so many here think that victims fall in love with their rapists.”

People are often raped by loved ones. It may be disturbing, but it’s nonetheless not necessarily wrong to suggest that there can be complicated emotions and relationships involved in an abusive relationship, especially when you’re talking about children.

The story that Jaime did is brilliant; the way some here are reading it takes greatly away from its power. This is of course my opinion, but I can’t help but see an appalling connection with the recent dialogue about the rape scene in Watchmen here. And, Calvin is not raped by a “loved one,” nor is Sally in Watchmen, so I fail to see that point entirely.

The point is that rape can be a complicated thing, that emotions between people can be complicated, and that abusive relationships between kids can be complicated.

Noah: I am sorry to disagree, but there is nothing complicated about rape. It is an act of violence however one wants to dress it up. Abusive relationships between kids are not very complicated; one of the children is dominated through force against his or her will. If there appears to be a complication it perhaps mimics battered wife syndrome, where the person in isolated by the abuser and cannot imagine a way out of the situation and begins to find strategies of survival. In the 1960-80’s there was no out for the kids in this story, they were isolated societally because if girls told they were raped they obviously asked for it, and to claim male rape would have resulted in total ostracisation … Any one looking at these toxic relationships is able to determine that they are those of abuse and violence. Just because the violence happens between children does not alter this pattern.

Haven’t y’all ever heard of Stockholm Syndrome? Noah’s right, humans are complicated.

Yes, I alluded to its counterpart in my comment on battered wife syndrome, however Stockholm syndrome is rather different: like battered wife syndrome where the victim has no escape– is isolated and the victim creates strategies to accommodate their plight. In that case they take on the ideologies of their captor; very similar with pimps and their captive women. What I’m getting at is that while the response can be pathologized, the act of violence is still very clear. One person brutalizes another and through the trauma of the experience the victim finds coping mechanisms. These responses do not arise from the pleasure of love, quite the contrary; they arise from ongoing and inescapable acts of domination, both verbal and physical.

To put this back into the story before us: the child is not isolated from social mores; he is still in the world where there is ample pressure from the outside that frowns on homosexual acts, which holds him in an untenable position, because he cannot seek relief (and because there is a threat to his family.) Transpose this to the idea of an abused spouse—even though she stays, she would not want her sister drawn into the circle of violence. There is an acknowledgement of fear. You will hear the phrase in this connection of walking on eggshells. Stockholm syndrome is different in that the victim takes on the ideological position of a (charismatic) leader-captor. This kid doesn’t want to convert people to his ideology…

Isn’t rape different from mere violence, though? It also involves sex of some sort, which is tied into intimacy. That can mess with a victim in a way that simply being pummeled on a regular basis would not.

A bit more:

With Calvin, his will is getting shaped by the recurring rape. He’s learning that this is what sex for him is like. It would be a simplistic portrayal to have him see things from an unmolested perspective, where he knows that this was wrong. That would suggest that the rape didn’t really have much of an effect on him.

Rape is not sex ever. Never. It is always an act of violence. Calvin is being shaped by a recurring act of violence, not pleasure. The conflict, if it arises, might come from the thought that in the first instance the child might have admired his abuser.

Charles: in certain respects your perspective helps support my point. Society has a hard time separating sex and violence and that fact is internalized by victims who are further traumatized, because their abuse is frequently understood societally to have a pleasure component and hence blame attaches to the victim.

More conflict..but not from desire ..from shame.

Note that I didn’t say rape is sex, but that it involves sex. That makes quite a difference. As for violence, that’s a complicated concept: Not all acts of rape are merely a manner of physically forcing the victim to have sex. Calvin came back, “willingly.” I don’t have a problem with calling that violence, but realize it’s a different type of violence from being held down, or punched in the face, or openly threatened. And, James, as if it needs to be stated, I’m not defending or dismissing any of this, only suggesting that rape has a lot of different effects on a victim’s psyche. In fact, I think it’s probably a lot worse than simply being beaten up, which is more easily externalized, objectified.

“Society has a hard time separating sex and violence and that fact is internalized by victims who are further traumatized, because their abuse is frequently understood societally to have a pleasure component and hence blame attaches to the victim.

More conflict..but not from desire ..from shame.”

It’s just not entirely clear to me that a young child is going to be able to easily separate sex and violence, or shame and desire, is the point. I think Jaime leaves space in the narrative for those kinds of confusions on Calvin’s part. And, as Charles suggests, the effect of those confusions is *not* to exculpate the perpetrator. Quite the contrary.

Marguerite,

“Society has a hard time separating sex and violence and that fact is internalized by victims who are further traumatized”

But with rape, isn’t that because it’s a form of violence that involves sex?

It’s not different from “mere” violence, it IS violence. There’s nothing intimate about being bent over and pummeled on the inside. He’s being literally ripped…it HURTS. He says it hurts over and over again and I do not see all this ambiguity…Jaime is very clear and direct in this case. Calvin is so young it’s extremely doubtful that he has much in the way of sexual impulse at all, boys that age are often like, “girls, yuck.” And again, there’s nothing he can do about it. Who’s he going to tell what is happening to him? His Mom who in her culture is relatively powerless at best, or his Dad, who simply isn’t there for his family? Let’s see, an 8, 9 or 10 year old kid exposing homosexual rape….in a Catholic community in the late sixties, early seventies? Even now in a whole ‘nother century, it’s a fight to legislate against bullying and look at how much resistance the Church put up against the exposure of the foul practices of so many of their clergy. So, please.

I wasn’t disagreeing with the assessment that it’s violence, but that all violence is the same. Some involves missiles, some penises.

All the social factors that you point to suggest that it would make rape much more difficult to cognitively assimilate to a normative cultural understanding than getting in a fight at school. The child is left on his own to figure out just what it means.

I’m not arguing that the character’s feelings are not complicated, but against the idea that he is jealous, that he has on some level enjoyed what is done to him and/or otherwise formed feelings other than fear, dread and anger (which are clearly shown on his face in every image) for that kid and so is jealous that he’s now directing his attentions to Maggie.

Well, I think everybody’s position is clear, and we’re all repeating ourselves at this point…maybe we all can agree to disagree at this point?

In any case, thanks to everyone for staying so non-confrontational about such charged material.

Pingback: Exes and Ohs | James Romberger