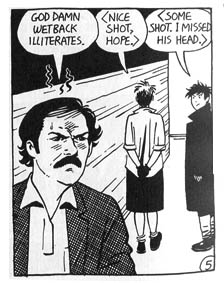

My first exposure to Love and Rockets came as a surly adolescent girl trapped in a level of Hell that Dante didn’t foresee—the suburb-meets-desert outskirts of Phoenix, Arizona. You can read virtually any recent news article about the place to imagine what a fun childhood that was sure to be for any kid surnamed “Gonzalez”—particularly one who oscillated between dysfunctional introversion, temperamental outbursts and endlessly sardonic sarcasm. (Given some of the racially based rudeness I was exposed to from both other kids and adults though, I regret nothing!) But after a divorce, remarriage, and determination to reinvent life someplace far, far away from New York in both geography and spirit, this was the place my (Irish-American) mother brought me to, to live out my teenage years as a Hopey Glass-type personality already on her way to an Izzy Ortiz adulthood.

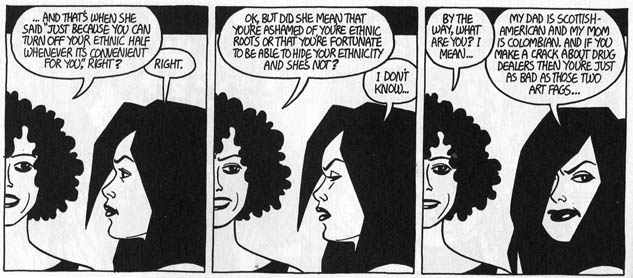

Love & Rockets came into my hands not through the local comic shop, where it was kept on an 18 & up shelf, but the zine rack of a Tempe based punk/alternative/whatever record store called Zia’s. Both Jaime and Gilbert’s work was wonderful, but the stories of the gang from Hoppers, the Locas, resonated with an immediacy to my adolescent self, due to the more recognizable factors – they were Latinas, but American ones as well, existing within both those cultures, as well as in the punk subculture. And did I mention that Hopey Glass was also of mixed parentage? An identity that was one, the other, both, none,a fact usually ignored but that could also be a source of contention.

It was all too easy to see where the punk scene could appeal to someone like Hopey in that respect, as well as the occult-obsessed and mentally unwell (see I told you I was well on my way) Izzy. Or even the constantly flustered Maggie (I know I haven’t mentioned her till now, but she never captured my imagination the way the others did. Young adult literature was already full of Awkward Insecure heroines who everyone secretly thought was a real Swell Gal.) When I was young, and those characters not much older, punk, death rock, et al were viewed as a mythical “safe zone” where it didn’t matter if you weren’t quite “right” or having an identity crisis. In theory it was the place to not only be a social outcast, but to make it yours on a whole other level. Even if that theory didn’t always work out in practice.

So there were these relatable elements, to be sure, but to me Jaime blended them with something beyond that yet also familiar (as is it’s nature) – magical realism, a style associated with, though not exclusive to, Latin American writing. This was especially prevalent in the earliest work, where fantastical elements would be introduced into the story in a naturalistic way, and it seemed that in Las Locas’ world, robots, dinosaurs, superheroes, and spaceships were viewed as though they were as ordinary as a weekend punk gig or a dramatic scene with your girlfriend or boyfriend. If anything, the latter seemed to have greater impact in the course of the story. Which I suppose gives weight to the critique that it’s essentially a punk-rock version of a soap opera, and I wouldn’t argue that point in the least. In several places the story seemed to dovetail from slice of life into again these fantastic elements, but in a way that seems highly self aware, as if it is the intent to create—not-a parody—but almost a meta-referencing of telenovellas, or of both American and Spanish comics. Rand Race in particular emphasizes this. If the Locas were relatable to me, Rand was a stiff cardboard cut-out of a human, a square-jawed, muscular male lead of the sort that would be found either in an adventure comic or a soap opera. And of course there’s Penny Century, a headstrong, adventurous young woman who can have nearly anything she wants—and who wants nothing more than to be a superhero. And hell—he even got in a classic feet-up “Condorito” iplop! here and there!

This blend of the familiar and the fantastic did for me what magical realism is supposed to do — gave me a sense of a world where there was so much possible beyond the mundane existence of my surroundings. Did I believe I would find a world of spaceships and dinosaurs? Well, no. But that I would leave Arizona, that there was a full spectrum of experiences to be had beyond what the majority of the culture around me was telling me I was limited to, and that even when I wasn’t sure if my demons were real or figments any more than I was about Izzy’s, it would be part of the full tapestry of being.

And maybe someday, I’ll find rockets, tambien.

______________

The index to the Locas Roundtable is here.

Nice. I’ll comment generally on the roundtable here because Jenny made such a personal connection with the work, which is I think what it is all about. Jaime and his brothers made a comic book which spoke to its readers, many of whom (women, gays, people of color, punks) do not see themselves compellingly reflected in many other places in comics, whose honest reactions shouldn’t be diminished and condescended to as those of fans and fetishists. I’m uncomfortable that every comic reader that isn’t a critic can be dismissively labelled as a fan, whatever that means. If someone likes to read Proust, are they called Proust fans? Most of the people doing comics are fans by that standard. The best cartoonists like Los Bros move and inspire their readers, likewise the great prose authors; in some of their readers arises a desire to express themselves in similar ways…or to engage in criticism. The fetishism in comics is in the collector mentality more associated with the mainstream, not the alternative. As comics begin to be collected in handsome hardcovers and placed in libraries and are the subject of dissertations, they are analysed through various lenses but that doesn’t alter their original impetus. I don’t think Jaime necessarily set out to make “short stories” or a “graphic novel” or any other kind of novel. Maybe the Hernandez Bros. do now generate their work for the GN format, but ’twas not always so. So, there is not much point in saying that a work is not something it never set out to be.

Good article. A lot of the stories Jenny describes are in The Girl from HOPPERS book. He really did a nice job during that period capturing the essence of the punk milieu. I wish he would’ve done more in that vein, ’cause as it stands it only amounted to a small handful of stories. It wasn’t too long after that he got into this tiresome “Will Hopey get back with Maggie or won’t she” storyline. Unfortunately.

Pingback: Locas…Y La Loca Perdida (guest column) « Notes From The Devil Dollhaus