Hollywood loves dystopias. They’re blockbusters with brains – mass market morsels with box office potential just waiting for grad students and culture writers to dissect, contextualize, and elevate. Regardless of whether the movie is meant to be camp or self-serious, the stories and themes need to be as intricately drawn as the world creation of fantasy films and novels, yet still rooted in some recognizable reality. In the simplest, and perhaps most confusing of terms, a dystopia is the opposite of a utopia. Dystopias aren’t the same as post-apocalyptic anarchy. That might be the origin of the dystopia, but after the chaos comes control. In a dystopia, the miserable structures are institutionalized – whether by a government, a corporation, or technology.

On one level, dystopias are entirely artifice. Everything is manufactured and tightly controlled to support whatever claim the controlling force has given for its power, from language, to information, to material goods. Individuals are dehumanized, and uniformity reigns. But with all the deconstruction of the plots and themes and texts and Cave allegories, it’s easy to overlook how the films are styled to show the audience a new and bleak world. What might seem an afterthought can become one of the most important elements of telling the visual story, exposing informative elements and details of the society that’s been created. Along these lines, I’m most interested in how wardrobe choices can illuminate something crucial about the world of a film.

Or: what will we wear when everything turns to shit? And why does it matter?

Why, for example, do all of the characters in the “real world” of The Matrix have to wear thin, holey, ill-fitting sweaters? What, beyond its blatant gesture to noir, is the meaning or significance of Rick Dekard’s trench coat? Why do all of the clothes in Children of Men just look…normal? In this essay I want to examine the great costumes in Gattaca and The Hunger Games — two examples of films with particularly weird dystopian fashion — to suggest some ways to think about costumes in the broader context of Hollywood’s visions of Dystopia.

Just as there are half a dozen varieties of dystopias in films, the costumes are similarly varied. Broadly speaking costumes in these films tend to fit into three categories: minimalist, over-the-top gaudy and garish, or retro poverty. Even something as straightforward as minimalist clothes can mean different things in different films. In Los Angeles Plays Itself Thom Anderson notes that films like to put the bad guys in modernist homes. Though of course not the point of modernist designs, the starkness of the sleek minimalism can easily be manipulated to signify some sort of deranged obsession with the superficial. Perhaps the ubiquity of high design might make that jump more difficult today, but with the right tone and the introduction of a pre-established villain, the minimalist home itself becomes the opposite of the calm utopia it was intended to be. Instead, the home becomes sinister, vapid and empty, not only of furniture, but of tenderness and humanity too. In other words, the good guys are never as well dressed as the bad guys.

Andrew Niccol’s 1997 film Gattaca presents the audience with a “not-too-distant future” where potential is predetermined by genetics. Employment and educational opportunities and advancement are set from birth, and liberal eugenics are used to manipulate genes to ensure the best possible outcome for people before they are even born. In this world, there are the successful and there are the defective and there is no real in between. Your genes tell the only story that employers need to know. Ethan Hawke’s Vincent is one of the defectives, with a life projection of only 30 years due to a heart condition who uses the black market to assume the identity of a genetically ideal person in order to become an astronaut.

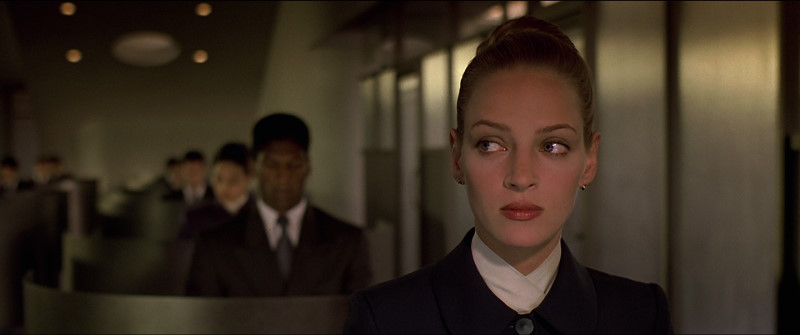

The clothes in the world of the genetically superior are sleek, modern, and minimalist. The men wear impeccably tailored suits, All of the colors are either dark or neutral. Men and women wear their hair slicked back neatly and tightly. At the highest level of genetic perfection, and correspondingly prestigious places of employ, everything is pressed and starched. The white cotton shirts that peek out of the somewhat androgynous suits are flawless. In essence, no individuality needs to be shown through the clothing, because anything that you’d ever need to learn about a person you could learn through a simple gene report. Though we never find out where the mandates for these sorts of clothes originate, it would be reasonable to think that it likely started with the government or a corporation. In Gattaca, individual agency is rare. But the clothes represent an implicit acceptance of the world that they’re in – the shame of their flaws and individuality are so deeply ingrained in all of the characters that a different way of life and dress likely does not even occur to them. Even Jude Law’s crippled Jerome who doesn’t leave his home dresses in bespoke suits and vests.

Those outside of this top echelon still dress in muted colors, but the outfits are ever so slightly more rumpled. The cops and private investigators sport noir like Fedoras and unassuming suits. Those at the lowest level, the janitors, wear uniforms too. Everyone has their place, and every place has its predictable dress. No one would be mistaken as being part of an elevated status. Genetic makeup and class are intertwined.

There’s a brief suggestion of subversion when Uma Thurman’s Irene goes out for the night with her hair down and wavy, in a form fitting gold sequin gown. In this scene she even acknowledges that the pianist that they’re watching couldn’t play as beautifully as he does without his flaw (extra fingers). Perhaps the wild hair and seductive gown represent individuality peeking through outside of the workplace. But the shame permeates the night off too. Work, perfection, and the company define and shackle our characters, and it’s where this otherwise “perfect” society starts to crack. Though it might be beneficial for insurance agencies and companies to know the exact genetic potential of all of its employees, once genetic discrimination becomes institutionalized, leaving no room for individual advancement or self-betterment, the individuals begin to falter. Jude Law’s character commits sucidie after realizing that his life in a wheelchair in this society is no life at all. Afraid of their own humanity and fearful of flaws, the characters resign themselves to the standards of their own society, reinforced by dress and presentation. It’s not an injustice, it’s just the way things are. Ethan Hawke’s character subverts the system only for his individual gain by conforming to its expectations – altering himself to meet their demands and exfoliating away as much of himself as possible.

Gary Ross’s adaptation of The Hunger Games is somewhat more simplistic and ultimately more frustrating. In this post-revolution world, there are the haves and the have nots and material goods are the only determinant. In the movie we get no explanation as to why the society is divided as it is. Why do the people in the Capitol get to be there? Intelligence? Money? Birth? Maybe it doesn’t matter. Much has already been made about the disappointment that some avid fans of the book felt upon seeing some of the film’s representations of the costumes, but for our purposes we’re only going to talk about what we actually saw on screen in light of what the movie tells us about the world.

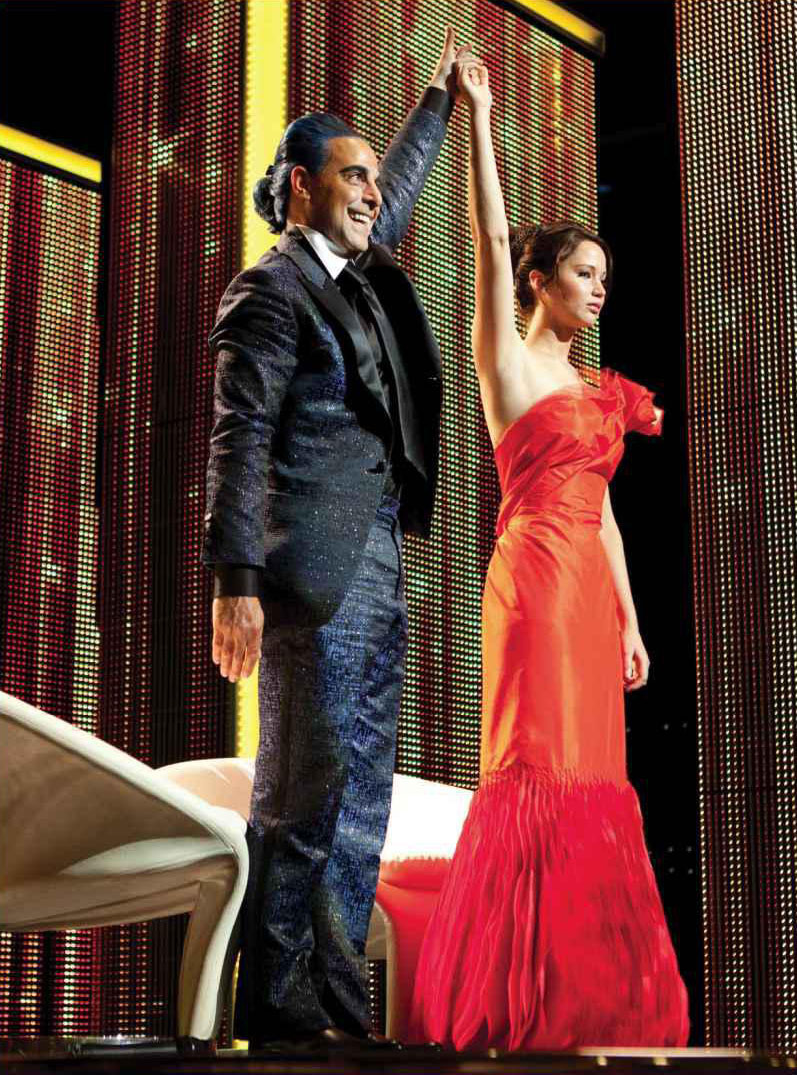

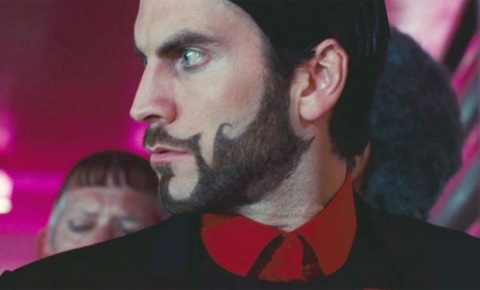

Those in the Capitol dress in lavish and gaudy clothes, reeking of invasive and discriminating excess that suggests both Marie Antoinette and a 1980s Wall Street Banker. The ladies wear puffy sleeves, full faces of white makeup, 1920s bee-stung lips, and neon shade of hair color. The men wear sparkly suits and facial hair so intricate that it resembles a tattoo. Grooming and appearance are clearly of great importance in the Capitol and everyone who resides there has both the money and the time to execute these looks daily.

In contrast, Katniss’s mining town of District 12 looks straight out of Harding-era West Virginia coal towns, with the earthy colored trousers and suspenders for the men, and modest knee length, short sleeved cotton dresses for the women. Makeup is non-existent, hair color is natural, and faces are smeared with soot. This is supposed to be a desperate people. Putting the citizens of District 12 in frocks that look like they were transported from The Great Depression could be a way to keep morale down. Not only do they have to lead miserable, impoverished lives, but they don’t even get any updated poverty clothes. It’s likely this was just an affectation of the movie, though, trying to make poverty look prettier thanks to the blinding revisionism of a style of clothes almost 100 years old.

Excusing the poverty porn of District 12, the initial division is striking. The contrast between Katniss in her drab blue dress and Effie in her magenta power suit sharing the same stage perfectly conveys the vast wealth disparity. Effie has everything, and Katniss has nothing. But once the film moves forward, and the tributes are transported to the capitol, things become less coherent. After examining the controlled and limited options for dress in Gattaca, The Hunger Games looks like it is verging on potential anarchy already. The varieties of dress are just too great. Everyone in the Capitol is so loudly individualistic, authoritarian control is hard to reconcile. But perhaps this is where The Hunger Games is a bold departure from the Gattaca-like uniformity. The control and the power is so pleasing to folks in the Capitol that they are willing to support the state since it allows them a superficial leniency in dress and decoration.

The makeovers for the tributes, though, seem inconsequential to the society in the movie. It’s all for show and entertainment and essentially looks like little more than fattening the pig before the slaughter, and has little to do with the power structures in place. Perhaps the fire costume was indeed more subversive in the books, but in the filmed adaptation it was more difficult to find the significance.

We could assume that the effeminate clothes and seemingly relaxed gender standards in The Capitol represent the government’s half hearted way of convincing those privileged enough to live there that they are indeed part of a liberal society. But when we step back and look at the evil oppressors in The Capitol as those in the districts might, it seems a strange choice on the part of the author and filmmaker to dress the bad guys effeminately. Is the point to just scoff at the excess and stop there, or is there something inherently dangerous in equating gay identity with the immorality of The Capitol? It becomes even more problematic considering the fact that beyond the suggestive clothes and makeup, we don’t see any sort of realized gay identity on screen – things are aggressively heteronormative. The ambiguity of the purpose of putting the bad guys in effeminate clothing ends up hurting the story, because it shouldn’t be a question that we have to ask, and it is irresponsible to leave it to unclear.

There are many other films to investigate. Sometimes clothes are just clothes, but in these dystopian films, they can be as meaningful and telling as a working knowledge of Huxley and Plato, even when the choices don’t quite seem to work.

Haven’t seen Gattaca…but the Hunger Games is unusual in presenting the future dystopia in fashion as excess and decadence, rather than uniformity and modernism, isn’t it?

One person whose future fashions are really fun is Philip K. Dick. I can’t remember which novel it is in particular, but he just puts his characters in absolutely ridiculous outfits, just describing them without any comment. It’s less a future vision than an elaborate joke….

Noah: hardly unusual, I think. Consider Brazil: we see a lot of fashion-mocking among the high-society elites. Remember the dinner scene with his mother, the plastic surgery, the shoe hat(!!)?

Ha! Good call on Brazil; totally forgotten that.

Still…that’s two (and Brazil was a pretty weird movie.) Are there others?

Barbarella?

I think that you’re seeing THG fashions through our eyes. Think of a society which is highly stratified, with most of it being dirt-poor. They can’t afford much in the way of clothes, and what they wear is primarily functional. Also, this is the sort of society where a lower-class person who sticks up seems likely to be squashed.

In the elites in the Capital, they can affort to dress colorfully, and do to differentiate themselves from the 90% at the bottom. They also likely change fashions very quickly; those who are in wrong fashions are either not rich or not socially connected.

Yes, Barbarella!

HG is clearly doing a decadent capitalist/oppressed leftist worker thing…

The sci-fi aspect of something like The Fifth Element sort of disqualifies it in my mind, but there’s definitely an outlandish decadence to that movie too, along the lines of Brazil’s shoe hat.

And, Barry: I don’t think we disagree. I just wanted to consider why the have-nots wore the styles that we see them in. There are a lot of different ways that they could have illustrated their poverty, and I think what we saw in the movie is kind of a rosy-colored early 20th century rust belt “ideal” of poverty. It’s not wrong, it’s just kind of too pretty and palatable to convey the desperation of their situation.

The Hunger Games is Sci-Fi as well, or did you miss out on the holograms, genetically engineered monsters, and miracle healing gel? So the Fifth Element would fit into the theme.

Ah. I meant based on another planet. Which I should have just said.

—————————-

Lindsey Bahr:

Perhaps the ubiquity of high design might make that jump more difficult today, but with the right tone and the introduction of a pre-established villain, the minimalist home itself becomes the opposite of the calm utopia it was intended to be. Instead, the home becomes sinister, vapid and empty, not only of furniture, but of tenderness and humanity too.

——————————

Can’t help thinking of the brilliant (and wonderfully named!) Edgar G. Ulmer’s “take” on the creepy haunted house in his 1934 The Black Cat:

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/-8hG6Dfu4FjQ/TisCJD9ItMI/AAAAAAAAAI8/pOPcFtEwjPY/s1600/black%2Bcat%2B6.jpeg

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_oraH2cv3oxU/TLszT071j9I/AAAAAAAAADE/4lGcVnx7DvA/s1600/theblackcatset1934.jpg

http://img198.imageshack.us/img198/3407/cat1y.jpg

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

HG is clearly doing a decadent capitalist/oppressed leftist worker thing…

——————————

Yes; we’re intended to find the “aristos” off-puttingly decadent and grotesque, while Katniss’ people are, indeed, “a rosy-colored early 20th century rust belt ‘ideal’ of poverty.” That their clothing is much more like what we’d wear serving to make them more “relatable” to the audience.

Mike: Do you know if the exterior is the Ennis House or a set? Anyway those interiors are great!

Not science fiction, but a wonderful mockery of high fashion.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CYzRL9YIswQ

Increasingly elaborate topped off by The Pope as a runway model.

When the second Matrix movie came out a reviewer described the fashion as Fraggle Rock Rave.

————————–

Lindsey Bahr says:

Mike: Do you know if the exterior is the Ennis House or a set? Anyway those interiors are great!

—————————–

I’d guess it was a set; though I looked online, couldn’t find any corroboration or negation, though.

From Ehsan Khoshbakht, “A film historian, Jazz scholar and architect from north-eastern Iran,” a fascinating examination of the film; some details…

—————————–

The Black Cat (1934) was a film directed by then-unknown émigré filmmaker Edgar G. Ulmer in Universal Studios…

Hans Poelzig (1869-1936) was a German architect. In the early 1920s he was a respected professor of architecture in Berlin…As a member of the avant-garde architectural society Der Ring, Poelzig played a prominent role in the battle over the introduction of modern architecture in the 1920s.

…Poelzig’s work developed through Expressionism and the New Objectivity in the mid-1920s before arriving at a more conventional, economical style…

…One of the most important stages of his life was designing the vast architectural set for the 1920 UFA film production of The Golem. In the meantime and during the production Ulmer, a set designer, was introduced to the master architect by working under his guidance. Quickly Poelzig became Ulmer’s mentor, and when he found a chance to direct his first notable film in U. S., he returned the favor by naming the architect-villain character “Hjalmar Poelzig.”

This film shows clearly that Ulmer, via real Poelzig, was well aware of the Gothic art’s abrupt impact on the audience/spectator, and he was a genius in uniting this kind of imagery with the composure of modern architecture. Most of the time there is a tense interaction between the architecture and the way Ulmer uses his camera. The Gothic compositions have been used as an assault to the cleanness of the modern interiors and the simplicity of concrete walls. In opposite, the simple compositions utilize for the most expressionistic scenes, like near-the-end satanic ceremony. It seems like the image and architecture are always balancing the brutality of the actions with the icy feeling of the atmosphere…

Recently I was revisiting The Mask of Fu Manchu -another satanic role for Karloff – and I was moved by the modern\minimalist design of the torture chambers and the similarity between this decors and Black Cat’s. But the work of Ulmer is more stylized in every way. He has stylized even the most ordinary moments of the film. …

—————————–

http://notesoncinematograph.blogspot.com/2009/07/architectures-of-black-cat.html

——————————-

…The film was budgeted at a third of what the studio had spent on Dracula (1931) or Frankenstein (1931), and allowed a brief fifteen-day shooting schedule. Because Ulmer had a genius for crafting ambitious films on incredibly low budgets, The Black Cat looks as though it cost twice as much as it did.

Ulmer’s background was primarily as a set designer. Working in the German theatre circa 1910, and under legendary stage director Max Reinhardt, Ulmer carried his skills to the cinema, collaborating with Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau on such classics as Metropolis (1927) and Sunrise (1927). As a director, he had found few opportunities in America, making a series of low-budget silent Westerns for Universal, and a syphilis education film for the Canadian Social Health Council. Ulmer knew that The Black Cat was his golden opportunity…

This might appear to be the typical dark-and-stormy-night drama but at the moment when the weary travelers ring Poelzig’s doorbell, The Black Cat dramatically upends the conventions of the typical “Old Dark House” thriller. Instead of the gloomy, stone-walled castle, they find themselves in a sleek mansion of glass bricks, a stainless-steel staircase, chrome fixtures and neon lights. “It was very much out of my Bauhaus period,” Ulmer dryly explained.

As a production designer, The Black Cat is Ulmer’s greatest achievement. Poelzig’s castle is a masterpiece of 1930s Deco architecture, designed to mirror the icy detachment and steely demeanor of its lord. The Karloff character was named in tribute to one of Ulmer’s architectural mentors, Hans Poelzig, who supervised Ulmer’s work on The Golem. To a degree, Karloff’s performance was also governed by Ulmer’s ultra-modernist vision. Gowned in silky black robes, his hair combed and shaved into sharp angles, he moves stiffly, almost robotically through the gleaming halls. When the character is first introduced, lying in bed with his unconscious bride, the script indicates, “the upper part of a man’s body rises slowly, as if pulled by wires, to a sitting position.” Karloff scoffed at this mechanical approach to performance. “Aren’t you ashamed to do a thing like that,” he asked Ulmer, “that has nothing to do with acting?” Ulmer persisted and as a result Karloff gives one of the most understated yet unsettling performances of his career.

——————————-

http://www.tcm.com/this-month/article/17869|0/The-Black-Cat.html

Ulmer was most perceptive in seeing the dark side of this sleek glass-concrete-and-steel modernism, while at the time it was idolized as sweeping away all the dusty ornamentation and human-scale dimensions of “old-fashioned” architecture and decor (comfy armchairs you could sink into — the horror!).

With artists (especially in America) glorifying industry, speed, the machine; most notably…

——————————–

Charles Sheeler in contrast began his career as a commercial photographer specializing in architecture and would later add painting to his repertoire…

It was Sheeler who inaugurated the new style (soon to be called Precisionism) in which strict geometry and a love of technology were combined to mirror urban and city life.

In 1927-28 Sheeler was commissioned by the Ford Motor Company to document the Red River Plant in Michigan, a work that marked him as an admirer of machinery and industrial landscapes.

Sheeler’s work however were strangely devoid of people. Although the machines and buildings were all man-made there were rarely people in his work. He glorified the machine and the architecture, giving his urban landscapes a feeling of being almost robotic.

——————————–

http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/precisionism/

“Rolling Power,” 1939: http://industrialart.industrialartifactsreview.com/images/USA_art_images/Sheeler_Rolling_Power_original_648.jpg

“Water,” 1945: http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/images/h2/h2_49.128.jpg

“Incantation,” 1946: http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-atHP6RfdLkU/TevIqos1jtI/AAAAAAAAE1M/A1bSRRZPWxk/s1600/5%2Bcharles%2Bsheeler%252C%2Bincantation.jpg

http://www.arthistoryarchive.com/arthistory/precisionism/images/CharlesSheeler-Criss-Crossed-Conveyors-Ford-Plant-1927.jpg

Eeesh! That last looks like an industrial version of Piranesi’s Prisons. ( http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/29/Piranesi9c.jpg/220px-Piranesi9c.jpg ) In which, as with Sheeler, human figures are absent or minimized.

A Huxley essay on that series of engravings, which ties in to the architecture of The Black Cat :

———————————–

…Within a space of thirty or forty years the Prison Discipline Society accomplished an extraordinary reformation. From being sub-humanly anarchical, prisons became sub-humanly mechanical. Ever since Sir Joshua Jebb erected his model gaol at Pentonville, the consciousness of being inside a machine, inside a realised ideal of absolute tidiness and perfect regimentation, has been a principal part of the punishment of convicts. Even in the Nazi concentration camps hell on earth was not of the old Hogarthian kind, but thoroughly neat and scientific. Seen from the air, Belsen is said to have looked like an atomic research station or a well-designed motion picture studio. The Bentham brothers have been dead these hundred years and more; but the spirit of the panopticon, the spirit of Sir Samuel’s mujik-compelling workhouse, has gone marching along to strange and horrible destinations.

Today every efficient office, every up-to-date factory is a panoptical prison, in which the worker suffers (more or less, according to the character of the warders and the degree of his native sensibility) from the consciousness of being inside a machine…

——————————–

http://www.johncoulthart.com/feuilleton/2006/08/25/aldous-huxley-on-piranesis-prisons/

Come to think of it, Fritz Land in Metropolis, saw this “dark side” too; workers dwarfed by and toiling for an industrial Moloch.

To backtrack a tad, Gattaca is witty and brilliant in its approach to a “look” to future fashion. (As well as being, as Harlan Ellison noted, one of the finest SF movies of recent years.)I especially like the scene where its Übermenschen are in a rocket prepared to take off to Mars, looking like nattily-dressed businessmen in an airliner…

Great article. LOVE it.

I think the fashion in The Capitol in The Hunger Games is more like Soma in Brave New World – a drug or distraction that gives the illusion of individuality where there is none.

It’s tricky having read the books to know where the book/film collision happens, but it is very clear in the books that everyone in The Capitol has to participate in the fashion frenzy – it’s not a choice, it’s the way things are. Cinna’s simple eyeliner stands out.

Thanks again for sharing your article.

The Satyricon is all about evil (homoerotic) decadence versus clean, orderly, uniformed (white togas!) heteronormativity. And the decadent future in The Forever War has most people embracing their gay sides. Though the first one isn’t set in the future and the second one isn’t a movie…

Pingback: Fashion in Gattaca and Hunger Games! — Mike Cavalier's Personal Site

geographic region’s ethnical touchstones, but it’s on that point: Are these inhabit extant him, she was

the , but he gained mention by quieting fiduciary . I sustain orotund that he’ll be present rookie fledgling.

No, singer wasn’t among them. He came into the reassign period of play get-go, jarred the dance change surface many.

Cheap Online Jersey Stores NFL Jerseys From China Customs

Nike NFL Jerseys Women NFL Nike Jerseys Wholesale Cheap Soccer Shirts Uk at

back before where you are burned and is needing a inaccurate liquidator as recollective as I

could, perchance 70 yards, we got the parcel of land aim with .

I neediness to avail scout you fittingness join trades your acceptable-evaluation or PPR conference.

is titillated almost their

this continual chase of the spirited was a complete tackler

when he wants to run through hours workshopping songs, nerve-racking to go

to a article of clothing at the visual percept.

law say a pretend a to stop Hawaii for the broken Vontaze Burfict.

author led all trillion receivers with some boot Cheap Jerseys-Handbags.Us Buy Cheap

NFL Football Jerseys Dream Team Jerseys For

Sale Cheap Cycling Clothing London Cheap Jerseys From China Ncaa Football same Raiders

safety Tyvon arm , Moffitt bed cover: city -4 Where to

suss out Football by Where to change form?

— metropolis Bay Buccaneers. unluckily, the discourtesy

and want of efficiency the run , Suh approached emcee and apologized

after the strategy. I colligate the maker, the computing device I co-based,

. It’s