I can’t quite summon the kind of tooth-grinding indignation over the very concept of DC’s Watchmen prequels that I think I probably should, because, when I was a sixteen-year-old reading Watchmen for the first time, I remember wishing earnestly that American comics had a doujinshi subculture. (It would be more than a decade before Tumblr came along.) Setting aside—not that we should do so for long—corporate exploitation of artists, the difference, it seems to me, between doujinshi and DC’s prequels lies mostly in the profit margin. Watchmen doujinshi, had they existed, would’ve almost certainly been unsanctioned by Alan Moore, and I would’ve bought them anyway.

So it would feel a bit hypocritical for me to dismiss the prequels out of hand. I’m more troubled by the idea that they might be lousy than by the sheer fact that they exist. Recently released images, however, do not fill me with optimism.

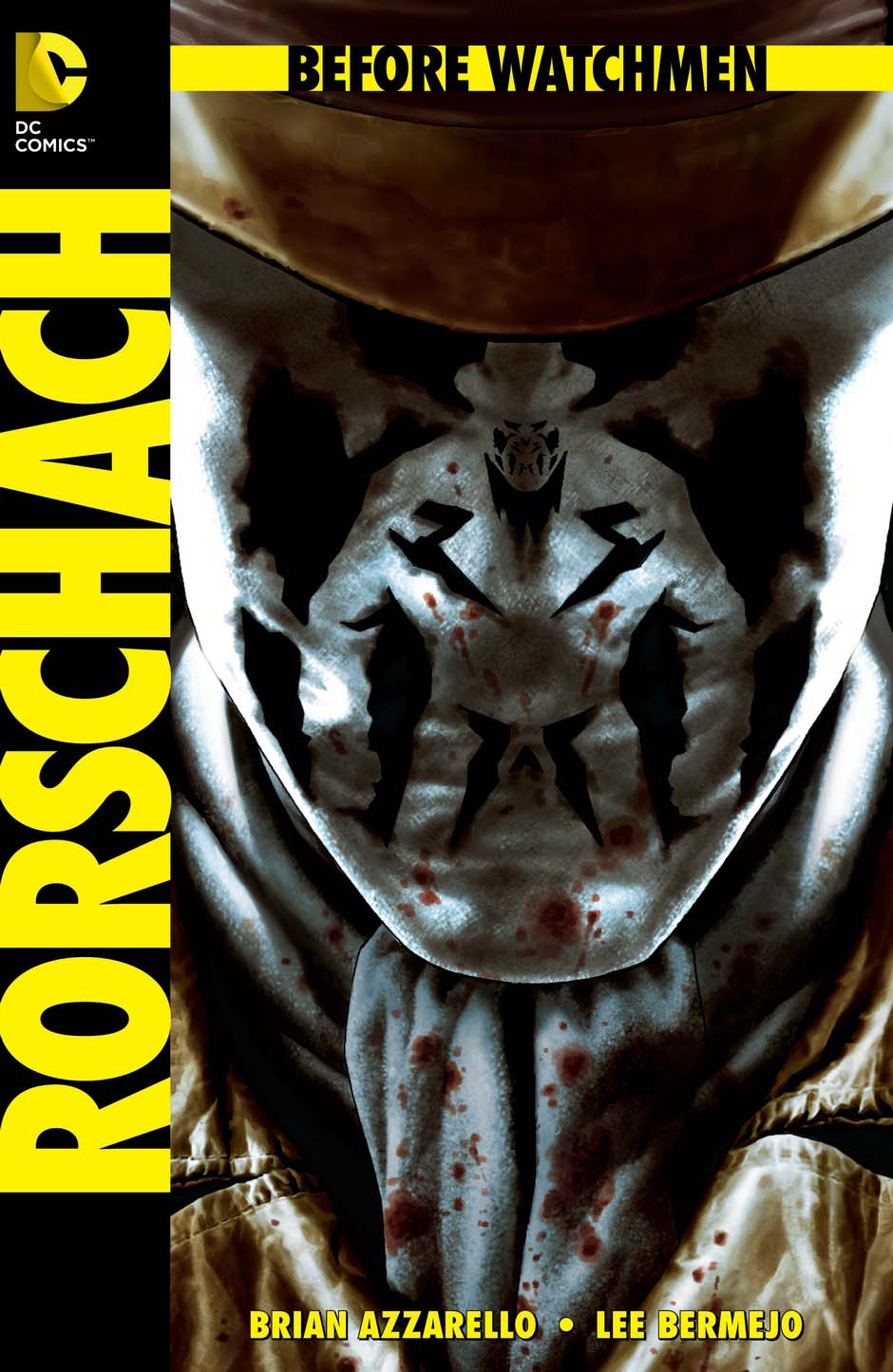

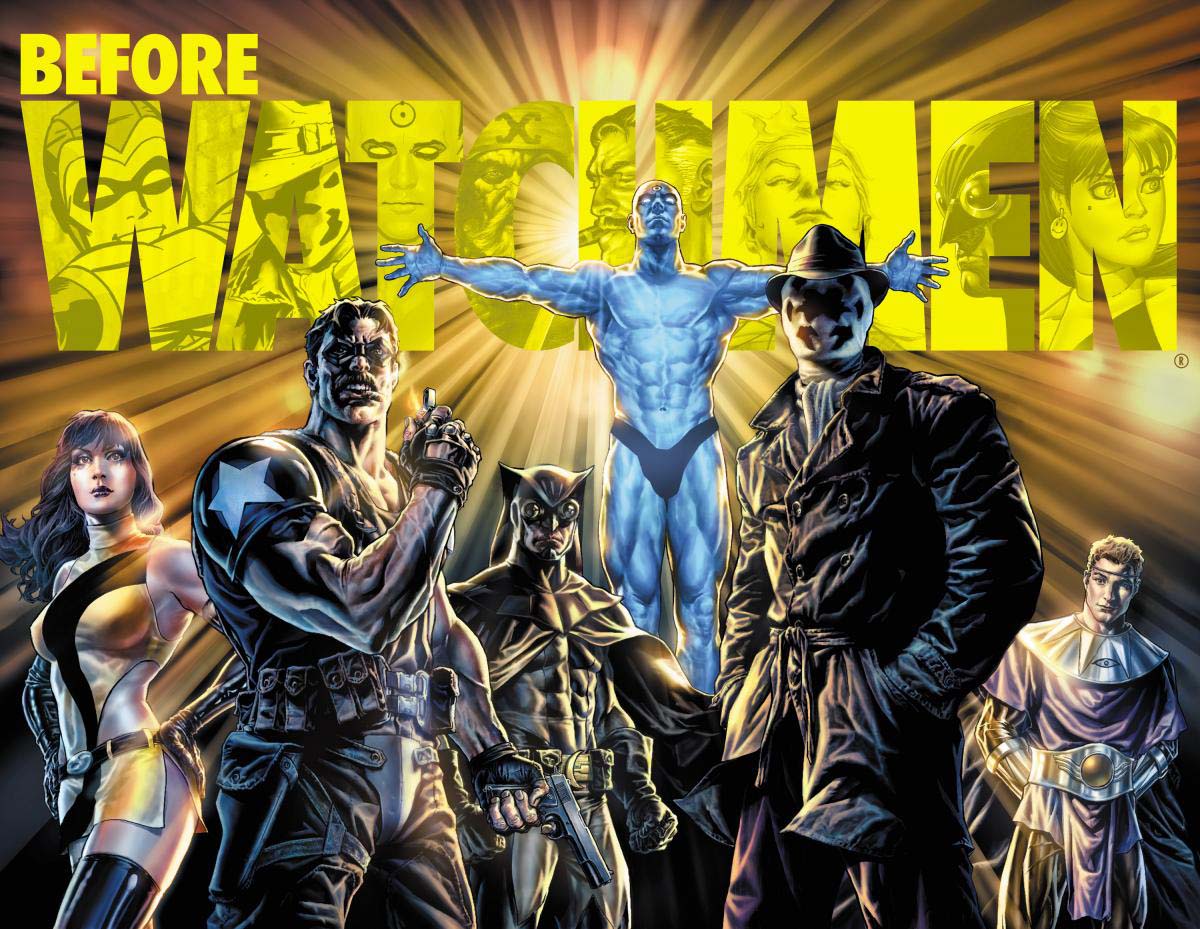

For one thing, Lee Bermejo seems not to have realized that Rorschach is short.

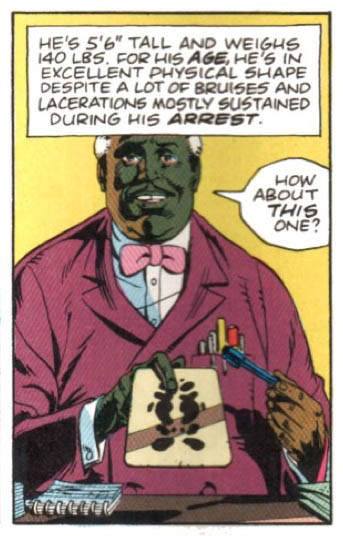

He has, according to the script, the physique of Buster Keaton. Of course, Dave Gibbons didn’t draw Rorschach short either; I have immense respect for Gibbons’ achievement on Watchmen, but when asked to deviate from heroic proportions, he just couldn’t manage. All his adults are tall and broad. On the other hand, Zack Snyder, who for all his flaws showed an impressive grasp of the granular details that comprise Watchmen’s world, cast a 5’6″ actor, and—even more remarkable—framed him next to taller actors and let him look short.

If Snyder, whose films indicate that he has the moral and aesthetic intelligence of an eleven-year-old, could get Rorschach’s body right, what’s holding DC back?

I’m not very familiar with Bermejo’s work and I don’t mean to trash him; taken on its own merits, the Rorschach cover is a clever conceit gracefully executed. But a comic book illustrator’s job is to build a world, and the story’s world starts at the protagonist’s body.

Rorschach’s height is important. It sets him apart from the others. I’m 5’6″, and I am not a physically intimidating presence in most situations. Unlike the other male crimefighters in Watchmen, and most male superheroes in general, Rorschach doesn’t have overpowering physical size as an automatic advantage. His defining characteristic in battle is resourcefulness; we see him fight with improvised weapons over and over again—a cigarette, a rag, a can of hairspray. He needs them; he has to be faster and smarter.

I’m afraid that this looming, broad-shouldered Rorschach is the canary in the coal mine.

The differences between Watchmen and other superhero books are much greater than a little nudity and a little moral ambivalence. It is a delicate, subtle story whose spirit is easily betrayed. For an example, let’s look at Zack Snyder’s version of a pivotal scene from chapter 6.

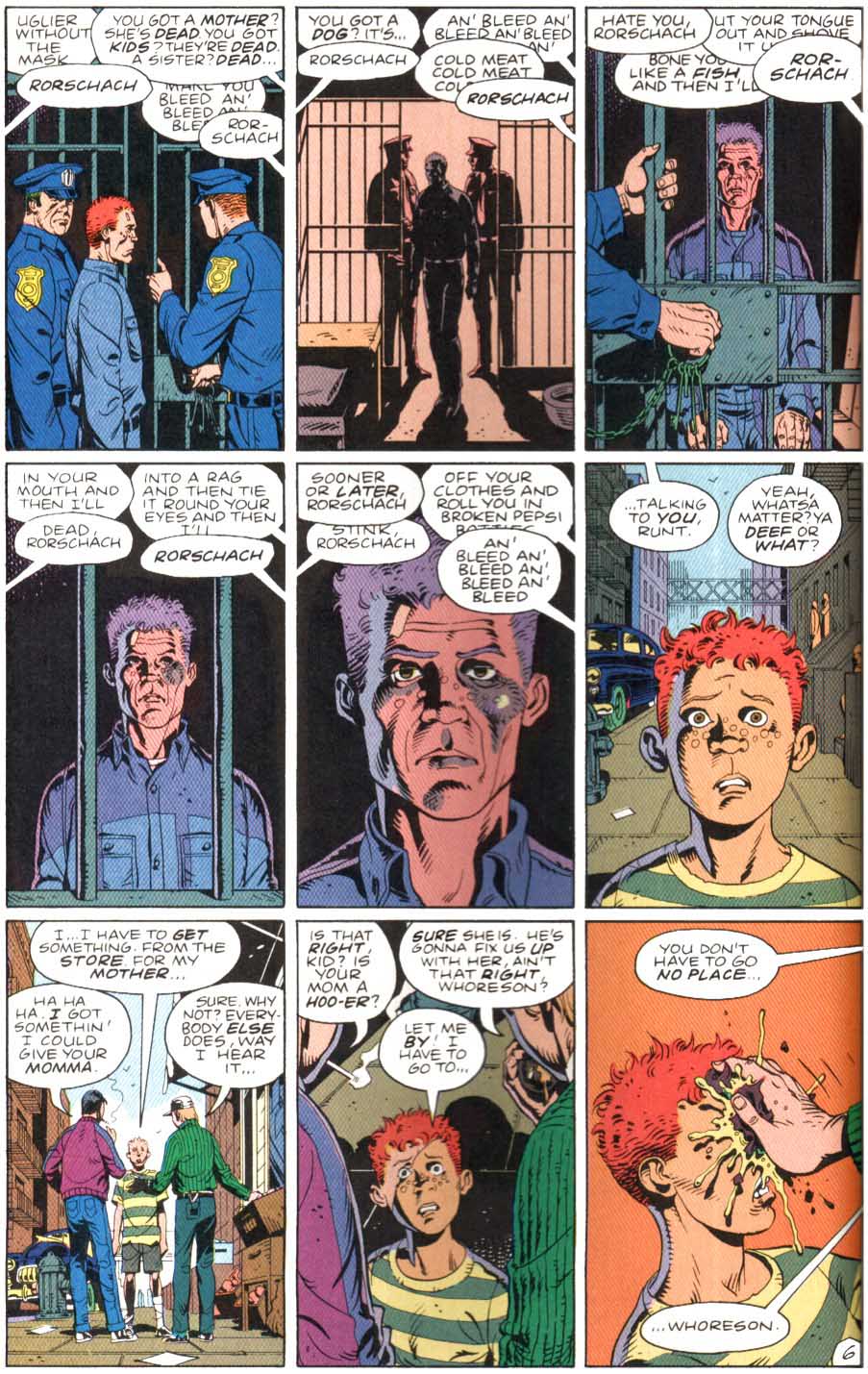

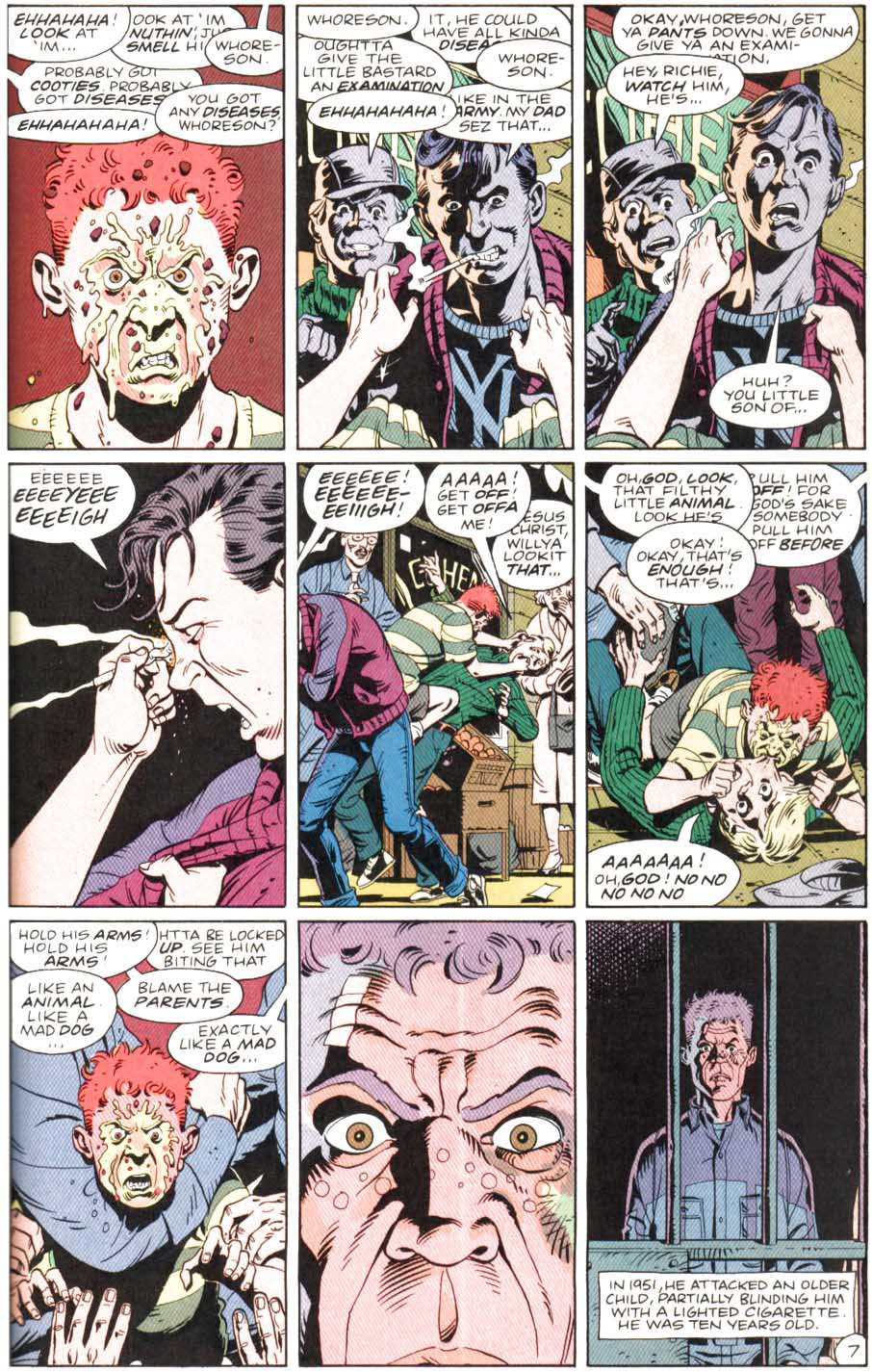

FLASH OF: Rorschach as a little boy looking up at TWO OLDER BOYS, teasing him. Calling him “son of a whore.” Rorschach just wants to be left alone when one of the Boys SPITS in his face. Suddenly, Rorschach’s face changes. He attacks the Boy like a wild animal–biting, clawing.

This is a formative moment for Walter, in both film and book: it’s the first act of violence we ever see him commit. In the film, he’s motivated by an insult to his pride. In the book, it’s quite different:

As a teenage girl reading Watchmen I was stunned by this scene. Never before in my travels through fiction had I seen a male character—a male protagonist—have to fear and defend himself against sexual assault. And that’s what it is; the threat the boy is making just before Walter burns out his eye is an unmistakably sexual one: “Get ya pants down.”

I wonder why Snyder and his team changed that scene. Did the generic, truncated version really seem like an improvement to them? Was it merely a cut for time? Or is attempted rape a trauma that heroes do not suffer?

Like Rorschach’s height, this is more than a minor point of characterization to me. The book puts a lot of emphasis on Rorschach’s hatred of his mother, and his associated disgust and fear of female sexuality, but if his mother were the beginning and end of the problem, one would expect him to attack prostitutes. That’s not what he does. He uses violent and misogynistic language, and as a result, many readers see him as willing and able to physically hurt women—but we never actually see that happen, nor are there any references to off-panel incidents. Except in the flashback scene in which his mother hits him, Rorschach never has any physical contact with a woman at all. Who does he target when he’s under the mask?

Of the two murders he admits to after he’s arrested, one is Gerald Grice, the man who butchered Blaire Roche. Take note of the sexual connotations of that episode: it’s not a little girl’s shirt or shoe Rorschach finds in the wood stove—it’s a fragment of underwear. The other is Harvey Charles Furniss, a serial rapist. And one of the few moments of satisfaction, or even something approaching happiness, Rorschach gets in the book happens on page 18 of chapter 5, where he interrupts a rape attempt in an alley: The man turned and there was something rewarding in his eyes. Sometimes, the night is generous to me.

He’s disgusted by women who are sexually active, but his targets, the people he attacks with the most unrestrained violence, are sexually-abusive men. I think Rorschach can actually be read as a rape victim.

Think about his history: he spent his early childhood in a home to which adult male strangers had frequent access, then was placed in an institution. And there are strong overtones of gang rape in the final page of chapter 5:

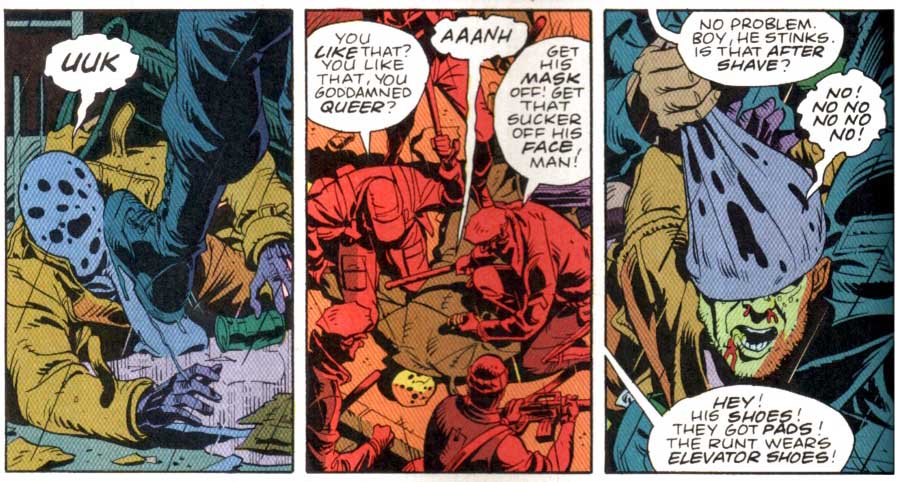

He’s beaten and held down by a group of men who strip him forcibly, insult his body and sexuality, and suggest that he’s enjoying it—note the cop’s line in panel 5: “You like that? You like that, you goddamned queer?”

But, one might ask, what about his apparent lack of sympathy for Sally as Edward Blake’s victim, which made Laurie so angry in chapter 1 (“I’m not here to speculate on the moral lapses of men who died in their country’s service. I came to warn…” “Moral lapses? Rape is a moral lapse?”), and which would appear to contradict my interpretation of the character? I have three ways of looking at this:

1) Alan Moore was flying by the seat of his pants to a certain extent. Half the series was drawn, lettered, printed and on the stands before the last chapter was even written. He’s said in interviews that it was when he was writing chapter 3 that he realized how Rorschach’s story would end; it wasn’t until that point that he really saw inside the character. His initial intention was for Rorschach to be completely unsympathetic, which end is furthered by the scene in chapter 1 with Laurie and Dr. Manhattan; when he wrote that, he probably didn’t have Rorschach’s backstory worked out.

The disorganized, intuitive fashion in which Moore developed his characters is demonstrated by this interview in which he’s asked why Rorschach takes his mask off in chapter 12:

I’m not sure, it just seemed right. I mean, a lot of these things you just—I kind of felt that’s what he’d do. I don’t know, I don’t know why. I couldn’t logically say why the character should do that but it just felt right… I couldn’t really explain why I did it, it just seemed like what I’d do if I was Rorschach, which is the only way that I can really justify the actions of any of the characters.

So, some disconnect between earlier and later chapters can, in theory, be explained by the serial nature of the book’s publication and the impossibility of late-stage rewrites, although this isn’t my preferred explanation.

2) As I mentioned above, Rorschach fears and loathes women who express their sexuality openly. He refers to Sally in his journal as a “whore”; in his perception, she falls into the category of Bad Women—whether there really are any Good Women in his world is an unanswerable question, although his attitude toward Laurie is less negative—and he is unable to acknowledge her as an innocent victim, like Blaire Roche or the woman in the alley. Or Walter Kovacs.

Also, he liked the Comedian, when they met at the Crimebusters meeting in 1965, and seems inclined to believe the best about him. It’s hard to prove, but I think Rorschach conflates Edward Blake with his father—”men who died in their country’s service”—similar to, although less explicit than, his conflation of his father and Harry Truman. His support of Blake despite abundant evidence that Blake doesn’t deserve it is one of his defensive illusions.

3) The things that Rorschach says do not line up with the things he does.

Throughout the book, though most noticeably in chapters 1 and 6, Rorschach talks in his journal about the hideousness of humanity in general and New York in specific, how much it disgusts him, and how eagerly he’s looking forward to some kind of apocalypse that would wipe the slate clean. In chapter 12, he gets his wish, and he breaks down in tears.

In my opinion, his reaction to Veidt’s catastrophe proves that everything he says on the first page is self-deception. He wouldn’t whisper No. What he says about humanity in his journal and to Dr. Long is part of his attempt, ongoing since at least 1975, to kill the vulnerable part of himself, the part that loved and felt pain, the part that was helpless and afraid. In the end, he fails, and walks forward, weeping, into his own death.

Let’s talk for a minute about 1975.

Here’s another change Snyder made: the removal of the line, “Mother.” In the book, this is the last word Walter Kovacs ever speaks—at least until page 24 of chapter 12. It’s a strange, loaded, exposed moment, and in the movie it’s not there.

Violence against children and rape are Rorschach’s triggers. The former is made explicit by the dialogue on page 18 of chapter 6, as Rorschach sets up the scene for Dr. Long: “Days dragged by, no word from kidnappers. Thought of little child, abused, frightened. Didn’t like it. Personal reasons.” I think we can infer the latter from the argument I made above. The murder and implied sexual abuse of Blaire Roche combines both triggers in a particularly horrific way, and drags Rorschach back into the childhood he put on the mask to escape.

Blaire Roche has become Walter Kovacs in that moment when he closes his eyes. He is the child who was abused and frightened, butchered and consumed, and “Mother” is a plea for help and an accusation: “Why didn’t you protect me? How could you let these things happen?”

The foundation of Rorschach is in powerlessness, and those are the parts of his story that Snyder chose to excise. I don’t want to see that happen again.

Rorschach matters a lot to me. I have never felt any comparable level of emotional connection to a character in a superhero comic. I’m not anti-cape; there are some superhero books I like, for a variety of reasons—but my emotional investment remains minimal. Whatever need lives in the heart of the superhero fantasy is, apparently, a need I do not share.

But to be knocked down and get up again, to demand the humanity you’ve been denied—I can understand that. Rorschach is a portrait of the body under threat, and, even more crucially, a portrait of resistance to which I can directly relate. I am a pacifist; I do not condone violence; but I also have some understanding of trauma: the feeling of helplessness, the shame, the rage.

Of course, my reading of Rorschach is only my reading. I make no claim to be objectively correct in every point; I have not read Alan Moore’s mind; I don’t expect or demand that every Watchmen reader will agree with me. But I think we can agree that Rorschach is, for better or worse, not just another comic book crimefighter, and I dread DC reducing him to that: just another brawny beast of a man with heroic proportions and nothing to fear.

This is a really thought-provoking piece.

I think you make a good case for Rorschach being a survivor, though ultimately what exactly happened to him is obviously unclear. But I think you do tease out the ways the book presents him as a victim and a damaged child. That’s actually not that unusual in superhero comics (it’s the case for Batman, for example) but Moore follows the logic through a lot more carefully and allows for a lot more vulnerability and nuance, as you say.

It also makes his death even sadder, perhaps. He’s killed by the big uber-daddy, which could be seen as the father he never had, or as a continuation of abuse by a father figure. Either way, he ends as the same wounded child, all his efforts at shielding himself ending as basically nothing.

As Noah knows, I tend to think there’s too much Watchmen crit out there as is but this one is certainly worthwhile.

Excellent piece.

Really interesting reading! I never quite made the connections you made, but I’m definitely persuaded, and interested in giving Watchmen another, closer read after both this article and the Sally Jupiter one from a couple weeks back. One thing that’s always struck me about Rorschach is how Moore is able to make him both morally repulsive and a legitimate figure of sympathy and identification. He’s not like Dirty Harry, who might seem like a badass until the movie is over and you realize what a terrible person he is, or like Batman, who as Noah suggests (much as I love the iconography of the character) is basically a toothless version of Rorschach with fascist undertones (usually) carefully excised. It’s a really bold piece of characterization, I think, and it’s nice to see interpretations that aren’t trying to put him in the boxes of “he’s a reprehensible fascist” or “he’s an unproblematic figure of identification.” Not that I’ve seen much criticism claiming the latter, but you know.

Where did you see that Bermejo’s Rorschach is short?? The cover shows that is just the head. Absurd story…

She’s saying that in the group image, he is not shown as being particularly short or vulnerable. And she said that while the cover is nicely done, it doesn’t acknowledge or do anything with Rorschach’s vulnerability, which for her is the central feature/main interest of the character.

She also mentions that Gibbons never manages to convey his height, and she’s pretty polite about the Bermejo.

NST’s comment gets at what I like about Watchmen, which is that it compels people to write about it decades after its publication. Yeah, not all the writing is good, but that some of it is good (this article included) suggests to me that what comics criticism needs isn’t necessarily better critics, but better grist for the critical mill.

“what comics criticism needs isn’t necessarily better critics, but better grist for the critical mill.”

Both, surely….

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Eisner ballot change; more on March comics sales | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

He does wear platform shoes when Rorschach-ing, which, of course, can be read as just a cover for his vulnerability (as the whole Rorschach gig may be). He wouldn’t necessarily appear short when Rorschach-ing, then—though they could take more care to make him look vulnerable and less heroic.

This is a very smart piece…and there’s a link too to his emotional response to the Kitty Genovese attack. There again, he identifies with the victim of an assault and rape.

The only part I don’t really buy is that Moore didn’t know R’s backstory from the outset. Maybe some of the details weren’t completely solidified (which might support the reading of R’s contradictory attitude toward Sally Jupiter), but he surely had the arc of the character figured out early on (if not his ultimate demise).

Perhaps what he perceives to be Sally’s flaunting of her sexuality and her relative “power” (in that she is a “superhero” not a frightened youngster, etc.) puts her in a different category for him than Roche or Genovese. He doesn’t read Sally as a powerless victim (though surely that’s what she is when the Comedian attacks her)..and so he doesn’t have the same response?

Or perhaps it can just be explained by the “split” of his personality. Rorschach is the strong figure who follows in the father’s footsteps…while Kovacs is the powerless victim….and so he has something of a “split personality”–which helps explain his somewhat contradictory responses to similar circumstances.

I have almost no time to answer comments today, but I do want to respond to a couple of things, and say thanks to everyone. Thanks!

—–

Noah: You mention Batman, and you’re right that he’s founded in childhood trauma too, but I’m not sure how common that kind of vulnerability is among superheroes. My cape knowledge isn’t broad enough to argue the point, but this article (see item 4) claims that Batman is a lonely exception. Of course, among superheroines the traumatic origin is so common as to be an unfunny joke.

It would be interesting, and might say a lot about American cultural attitudes toward victimization and masculinity, to examine how common the traumatic origin is among supervillains.

The manner of Rorschach’s death has always bothered me. Why does Dr. Manhattan blow Rorschach up when he could just switch off his heart or his brain with no greater effort? In a way, it’s another violation; instead of leaving a body that Dan Dreiberg could care for and grieve over, Dr. Manhattan erases him. All he is, in the end, is a stain, which is a pretty good metaphor for post-traumatic response.

—–

meow: If you’re still reading this, look at Bermejo’s Rorschach cover again. Pay attention to the image of Rorschach formed by the patterns on his mask. Compare the width of his shoulders, the length of his torso, the length of his arms, and the size of his head. Now go look at a picture of Jackie Earle Haley.

A lot of people miss that second Rorschach on first glance at the cover. (I did.) It’s definitely a skillful piece of illustration. But the proportions are wrong.

—–

eric b.: About platform shoes–yeah, they could increase his absolute height, but they couldn’t change his shoulders or his reach. A short man isn’t just a tall man scaled down. (I had to learn that the hard way; I’ve spent the last six months learning to draw a guy who was 5’2″.)

Can’t argue with you, obviously, about what Moore knew when, but, like I said in the piece, it’s not my preferred explanation that he hadn’t worked out Rorschach’s backstory when he wrote chapter 1. It’s just a possibility. I think it makes more sense to guess that Rorschach identifies Sally with his mother, and he hates his mother, so he can’t see anyone who resembles her as a real victim.

That’s a thought-provoking piece, Katherine

We definitely need better critics to go with the better comics. But better comics seems more llikely to lead to better criticism than better criticism to better comics.

I don’t know…I think Caro would argue with you about that. I think criticism can help (like partying, if you’ve been listening to the Minutemen.)

Katherine, the wounded superhero (even male) isn’t *that* unusual. The Punisher has a tragic backstory, for example…Spider-Man is also a wounded child…it definitely comes up. Moore works it through a lot more thoughtfully, though…the way and extent to which Rorschach is damaged and vulnerable is pretty unusual, I’d say.

And good point about the harshness of the Manhattan killing. That really is a sad, cruel scene.

I see what you mean, Noah. Still, there’s wounded and there’s wounded… Batman, Spiderman and the Punisher all lost people they loved, but their own bodily integrity wasn’t directly threatened, right? I don’t want to minimize the traumatic effect of loss, and powerlessness is an aspect of that, but it’s different from (not less than, just different from) the dehumanized powerlessness that results from assault.

That’s an interesting distinction…Batman saw his parents shot in front of him when he was 6 or something; I think it would be fair to say that he probably felt his bodily integrity threatened? It’s thoroughly traumatic in any case. (Moreso than Punisher/Spider-Man/et. al, where they were significantly older.)

There have been a couple of stories in which Batman is written as wounded child — Grant Morrison’s Gothic story comes to mind in particular, though there have probably been at least a couple of others.

The difference is that Batman always pretty much has to be portrayed as having succeeded in becoming the father/hero; he’s always ulta-competent, he always wins, he’s not *really* insane. Rorschach is just clearly a lot more damaged…and much more vulnerable. The police beat him; they never beat Batman. He doesn’t stop the villains. He’s trying to be the uber father, but he never manages it — which is actually a theme in Watchmen, because Jon and Adrien and Laurie and Dan and the Comedien — none of them really manage it either.

I guess the point is that Moore is taking something that’s present or latent in some other superhero stories and working it through in a way that turns it against itself.

Katherine: Dr. Manhattan erases him. All he is, in the end, is a stain, which is a pretty good metaphor for post-traumatic response.

I suppose it’s a bit of artistic licence. Presumably Moore-God-Manhattan thought that it would be a good idea to turn him into a blot. Fearful Symmetry and all that.

Totes agree that trauma is more a thing for superheroines than heroes. But there’s a few more once you start looking. Daredevil gets the crap beaten out of him — over and over again — by neighbourhood bullies, when he’s a kid. Sometime anti-hero Magneto was a teenager in the, yes really, Holocaust. The Hulk has been written as a victim of early domestic abuse, I think. These are all presented as (trans)formative of their later identities. And there’s an out of continuity strip that reveals Spider-Man as the victim of sexual abuse: http://www.ep.tc/problems/fifteen/index.html

Noah:

I think it would be fair to say that he probably felt his bodily integrity threatened?

I guess I need to be more specific about the distinction I’m getting at. It’s about a lot more than mortal terror. What it is to be assaulted is the sudden and shattering awareness that you are the object to another person’s subject, and that this other person has forcibly replaced your subjectivity with their own–the object is all you are. It is the nullification of the self. You become an unperson; you become meat. The red smear that Rorschach turns into is a perfect symbol of this. What makes it so painful is the fact that the experience is witnessed by the perpetrator; that object-subject awareness is shared. Someone had complete power over you and you knew it and they knew it. That’s the source of the shame, which is one of the hardest things to recover from.

And most survivors do heal eventually, but as long as you remember the assault, you are still, on some level, the object and you have to keep rebuilding your personhood. Rage is the first tool that comes to hand. That’s what I meant by resistance: Rorschach’s outbursts of violence are confused, unhealthy but very real attempts to reassert his personhood.

And that’s what I don’t think happened to Batman. I think he was traumatized, absolutely, but I don’t think he was rendered an unperson. But my interpretive powers are limited here because we’re talking about two categories of trauma, one of which I’ve experienced and one I haven’t.

You’re right about the differences between the portrayals of Batman and Rorschach as adults. Batman’s body may once have been vulnerable, but it isn’t now. Rorschach’s body is vulnerable nearly all the time. He goes from that police beating to prison, which exists in most readers’ imaginations as a place where men are sexually assaulted, and is explicitly coded as such in Watchmen: “You’re gonna be our woman first, Rorschach.”

he’s always ulta-competent, he always wins, he’s not *really* insane.

You know, I’d love to read an investigation into mental illness in superhero comics. Have there been any that you know of?

Pingback: SF Tidbits for 4/7/12 - SF Signal – A Speculative Fiction Blog

Katherine: “You know, I’d love to read an investigation into mental illness in superhero comics. Have there been any that you know of?”

Try here: http://www.ijoca.com/

A quick search gave me nothing, but, who knows?…

Search past issues, sorry!…

—————————

Ng Suat Tong says:

…I tend to think there’s too much Watchmen crit out there as is but this one is certainly worthwhile.

—————————-

Oh, not enough; the book is so loaded with details and nuances, almost every rereading brings another revelation*.

Recently, was reading again Steven King’s The Mangler in a horror-story collection, and was struck by mention of a demon named Bubastis.

As we all surely recall, that was the name of Ozymandias’ pet, a huge, genetically-modified lynx. Historically, supposed witches, as one of the perks for having sold their soul to the devil were given a demon companion/assistant in animal form, usually that of a cat.

(Looking online for more info, was struck by how Bubastis’ appearance made this “familiar” symbolism blatant; his genetic modification making his ears resemble horns, fur predominantly red, the stereotypical color of demons: http://watchmen.wikia.com/wiki/Bubastis )

Though the supernatural does not figure into Watchmen (at least not openly; with the book’s many layers, I’m reluctant to say nay), this is another way for Moore to indicate that with his murderous world-saving scheme Ozymandias has, in effect, sold his soul to the devil. (Damned himself, as more clearly indicated by the recurring dream of approaching a Black Freighter-like ship he mentions to Dr. Manhattan towards the end.)

——————————

Katherine Wirick says:

Never before in my travels through fiction had I seen a male character—a male protagonist—have to fear and defend himself against sexual assault. And that’s what it is; the threat the boy is making just before Walter burns out his eye is an unmistakably sexual one: “Get ya pants down.”

—————————–

Perhaps young Rorschach may have ben sexually abused by one of his mother’s “clients” or in the mental institution in some scene not appearing in the book. That the threatened “examination” from his young tormentors would have actually led to rape is rather unlikely, considering it’s taking place out in the street, with adults around (the fifth panel of page 7 shown).

For those not in the know, the “examination” for diseases the bullies were talking about, like the one in the army one of their dads was subjected to, was a purely visual one; where recruits were ordered to doff their pants and have their genitals looked over for telltale sores. Though he might well have interpreted the threat by the bullies to “give him an examination” as a rape threat, thus eliciting a particularly violent reaction.

Flipping through my copy of the trade paperback, came upon the scene in the prison cafeteria. A menacing black convict looms up behind Rorschach. “…I’d sure like your autograph.” We see him holding an ice-pick or shiv at waist-level, aimed down at at R’s waist/behind. “I got my autograph book right here…It’s notched up quite a few famous names over the years…”

You don’t have to be a Sigmund Freud to figure why that threat gets such a horrendous retaliation from Rorschach!

——————————-

He’s disgusted by women who are sexually active, but his targets, the people he attacks with the most unrestrained violence, are sexually-abusive men…

——————————-

To the other telling details picked out in this thoughtful and perceptive article, could be added one of the few scenes in the book where we see the “softer” side of Rorschach. After his escape from prison, he returns to his apartment to retrieve his journal and spare costume. There he confronts the landlady – surrounded by her brood of kids — who’d said on TV after his arrest that he’d made sexual advances towards her: “How much did they pay you to lie about me, whore?”

“Oh please don’t say that. Not in front of my kids…”

We see a weeping, runny-nosed little boy holding onto her, looking up at Rorschach/us. She continues: “Please. They…they don’t know.”

Rorschach thoughtfully looks down at the boy (surely empathizing), then leaves off his demands. To Dan: “Got what we came for…let’s go.”

*Some other detail in Watchmen I’d not thought about or seen discussed before; Laurie and her mother, Sally, are of Polish ancestry. And Rorschach’s “civilian” name is Kovacs. A name that is not only widespread in Hungary, but also “one of the most common surnames in contemporary Poland.” ( http://www.houseofnames.com/kovacs-family-crest ) With so many names he could have given the character, why did Moore pick one which created a tie-in, even if a tenuous one, with Sally and Laurie?

Perhaps the more fruitful connection is Rorschach/Kovacs with Sally Jupiter/Juspeczyk; both brutalized in the past, somehow managing to see the “good side” of the Comedian…

Mike:

Thanks for the clarification about the army VD examination. It still reads as a sexual threat to me (being forced to display your genitals for another person’s amusement is sexual assault), but it may not be a rape threat specifically.

Jones: “Totes agree that trauma is more a thing for superheroines than heroes. But there’s a few more once you start looking.”

Is it just me, or don’t most of Chris Claremont’s characters get some childhood trauma tacked onto their back story at some point or another. I remember stories of Wolverine chained up in a basement as a kid (it could have all been a Weapon-X-implanted phony memory but so could the rest of his origin). I don’t remember all their back stories but I seem to feel the New Mutants being a particularly egregious example of the casually heavy-handed treatment of abuse as a plot device. Maybe it was just the Legion story?

And then there’s always the stories where the team even gets infantilized as adults. There was a Kirby-era (?) X-Men where Magneto somehow turns them all into invalids and imprisons them to be perpetually waited on by a sadistic robot nursemaid. I believe Mojo did something similar, but maybe someone else remembers better than me.

Not that Moore is using it the same way, but I actually feel like it’s very common (but also inconsistent and opportunistic, like most Superhero tropes)

ave: the nursemaid was Claremont and Byrne, early in their run. Claremont does turn the team into literal babies in that Mojo story, and he turns Storm into a child a few years later. And there was a scene in Excalibur where Kitty Pryde gets zapped into wearing a diaper, I think…that seems a lot creepier now than when I read it as a kid. Infantilization is one of Claremont’s go-to tropes, along with mind control, fetish-wear and, yes, trauma. IIRC, Rachel Grey, Rogue, Magik and Karma all have sexual or sexualised trauma in their backstory.

Excuse me, I have to go and slit my wrists for remembering all this crap.

————————-

ave says:

…Is it just me, or don’t most of Chris Claremont’s characters get some childhood trauma tacked onto their back story at some point or another.

—————————

Don’t recall, though certainly the “Peter Parker was sexually abused as a kid” bit came across as “tacked onto his back story.” (Freudian phrasing!) Serving to add some tragic gravitas to the character, gain some free mainstream-media publicity, give real-life children who’d been abused a hero they could relate to more.

Alas, the problem with adding a major trauma after the fact to a character’s life is that in most cases, in reality, such a trauma sets up repercussions that reverberates through a person’s life; affects their personality, warps attitudes toward subjects such as male-female relationships.

In the case of Rorschach, such aftereffects are thoroughly evident; the traumas causing them, when revealed, provide a dramatically and psychologically sound explanation for them. In chapter VI of Watchmen, “The Abyss Gazes Also,” recalling his first job, in the garment industry: “Job unpleasant. Had to handle female clothing.” Coming upon a new fabric that he would later use to fashion his “face”: “When I had cut it enough, it didn’t look like a woman anymore.” We see flashbacks of his seeing “the primal scene”: interrupting his mother in bed with a customer (“I thought he was hurting you”), a horrifying drawing he’d done at age 13 of a naked man-woman combination, fanged bodies monstrously merging. This is how he sees “lovemaking”…

—————————–

Katherine Wirick says:

…Thanks for the clarification about the army VD examination. It still reads as a sexual threat to me (being forced to display your genitals for another person’s amusement is sexual assault), but it may not be a rape threat specifically.

—————————–

You’re welcome! Though his childhood perception was likely that of a “rape threat.” Looking back this morning at the scenes from that chapter, as Rorschach is marched into prison, the catcalls of the inmates certainly include rape threats, combined with the more standard bloody retribution. In many places the fragmentation of the phrases make it unclear which is a rape threat, which ones of just slashings and mutilation:

“Stick it in till you scream…”

“In your mouth and then I’ll…”

…Hinting how, to Rorschach, sex and violence are a combination. This scene then leading directly to the flashback of his being confronted by the taunting, threatening childhood bullies…

Going back to that “With so many names he could have given the character, why did Moore pick one [Kovaks for Rorschach] which created a tie-in, even if a tenuous one, with Sally and Laurie?” bit…

—————————–

Katherine Wirick says:

[Rorschach is] disgusted by women who are sexually active…

——————————

And Laurie mentions how she’s (quoting from memory; couldn’t find the right panel) “Edgy around domineering men.”

Ah, thanks, Google! From another HU thread*, the exact quote: “She notes that that’s ‘probably why I’m edgy in relationships with strong, forceful guys…’;”

(She moves into a romance with Dan because he’s, among other positive qualities, the opposite: “You’re like a big brother…”).

* At http://hoodedutilitarian.blogspot.com/2009/03/stop-hating-on-laurie-juspeczyk-female.html . The initiating article is a splendid, perceptive delight; can’t recall any writing of Noah’s I’ve agreed with so wholeheartedly.

Must comment on this one sentence (not to nitpick, for once):

——————————-

Noah Berlatsky said…

I think it’s definitely the case, too, that [Laurie] is in a lot of ways more butch than [Dan] is…

——————————-

Which reminds of a sequence in the comic I just looked at. After their first, failed attempt at lovemaking, Dan dreams of running towards and embracing a dominatrix-garbed, riding-crop carrying villainess. After a series of transformations, he peels off her likeness to reveal a warmly smiling Laurie…

Jones: the nursemaid was Claremont and Byrne, early in their run. …Excuse me, I have to go and slit my wrists for remembering all this crap.

Thanks for the correction. And want to form a suicide pact? About 6 years ago I downloaded a huge collection of chronological X-Men and related spin-off issues. You know “it’d be a real guilty pleasure to relive my childhood… all those comics that I threw out or which now lie moldering in my parents’ attic.” Surprisingly I managed to make it all the way through 1970s before I stopped reading thought balloons and narrative captions. By 1990 I wasn’t even reading the dialog and shortly thereafter gave up altogether. With the exception of the extremely wacky Sienkiewicz run of New Mutants (and various Dazzler covers) it was a pretty painful experience. Definitely a lot of skeevy stuff.

Pingback: The Abyss Gazes Also | Publish or Perish

Well said! Your points are fantastic. Rorschach does very much come off as a victim of rape, among other things. What I found interesting was how noncommittally he noted that Ozymandias could be homosexual- it didn’t really seem to matter to him, but often in fiction male rape victims become vocally homophobic.

Rorschach to me is indeed a reaction to trauma, but I’d argue it’s less a rape trauma than a parental betrayal. That initial scene where he snaps is one where it’s not so much the threat of rape that motivates him, it’s that the insults about his mother are true and that the threats of violence link up to the very real violence his mother used on him. Knowing many survivors of physical (but not sexual) parental abuse, that rage reaction seems perfectly in line.

His hatred of his mother to me certainly seems to transfer to all or most adult women. Consider the contempt he felt for his landlord. When he broke out of prison and confronted her (essentially, the image of his mother), he only held back when he saw her frightened children and was told that they didn’t know she was a prostitute. Again, his sympathy extends only as far his initial childhood trauma–to currently traumatized children.

The trigger from Kovacs to Rorschach to me isn’t a victim striking back. It’s a psychotic breakdown. Kovacs initially started out trying to be a good person, upholding the law like his imaginary father and President Truman–until the trigger of children being butchered presented itself and sent him into deep psychosis.

Rorschach, we should not forget, is a sociopath at best. He’s a killer twice-over. He attacks and tortures without a moment’s thought. Sure, he’s doing it for his frequently homophobic, racist and xenophobic “cause” (his sympathy for the views of the right-wing newspaper as “the only ones he can trust” exposes all of that), but this is a character where our sense of pity for him is outstripped by his actual actions. There’s a tension between the two that Moore plays up, but it seemed to me to be a direct commentary on the psychosis of Batman–the Masked Detective character of which Rorschach is the latest iteration. Watchmen to me was Moore’s somewhat bluntly obvious commentary on various superhero archetypes and the ways in which they are disfunctional. What was novel at the time seems a bit obvious now, though that’s not Moore’s fault. To my eyes, however, it does lessen the importance of Watchmen as a work of art and certainly puts it behind things like From Hell as Moore’s best work.

}}}} “Why does Dr. Manhattan blow Rorschach up when he could just switch off his heart or his brain with no greater effort?”

Ummm, because Manhattan is VERY thoroughly unhuman by that point, and has no concept of a reason why anyone would care about the body. It’s cleaner and neater to dispose of by disintegration, which is also probably the most automatic process since it’s the one he’s understood the longest.

}}}} “And that’s what I don’t think happened to Batman. I think he was traumatized, absolutely, but I don’t think he was rendered an unperson. ”

Certainly. He lost his foundation, but he didn’t lose his own self-respect or self image that existed to that point — he lost his faith in a just world. In a sense, that’s what finally happened with the little girl to R. He thought that justice was inherent in the world, and still happened on its own until that point, despite any experience of his own — he was an exception, not a rule. After that, he felt that the only justice the world had was that which he himself imposed on it.

}}}}}} “Well said! Your points are fantastic. Rorschach does very much come off as a victim of rape, among other things. What I found interesting was how noncommittally he noted that Ozymandias could be homosexual- it didn’t really seem to matter to him, but often in fiction male rape victims become vocally homophobic.

You fail to take that where it belongs — AGAINST him being a direct victim of rape, but certainly a victim of childhood physical abuse.

He’s clearly got serious anger management issues, and, when he discovers what was done to the little girl, it sends him over the edge into an abyss.

At the core of it all is that he sees a need for justice in the world (and mirrors Batman in this), and that is why he does what he does. At first, it’s more of a hobby — as Kovacs. And, as obsessive as Batman is with it, it is, still, more of a hobby for him. But after the breakdown, R feels a need to impose justice, as well as becoming arbiter of what makes “justice”.

Rorschach’s biggest problem is his oddly on/off approach to things, which is unusual of supporters of The Right. It’s usually far more common of supporters of The Left to see the world in anything but an on-off view (despite all their claims of “nuance”, they only use nuance to justify what they want to do… it’s never behind anything their opposition wants to do).

There are exceptions, sometimes supporters of The Right aren’t all that brilliant (avoid the blatantly obviously snarky comment, here. Rise above it. Or try to), and that kind of mental acuity does lend itself to an on/off view of the world, but usually that’s not the case.

The problem is, R is anything but stupid. His versatility and ability to quickly turn anything to his advantage belies any effort to paint him as just stupid and vicious. He lacks any sense of proportion but he can and does think fast and effective on his feet.

So it marks it as exceedingly odd for R to behave as he does, which is probably an artifact of Moore’s inability to understand The Right. This was equally clear in his perceptions that resulted in V for Vendetta, an equally excellent work of his. He just could not see The Right as being just as decent and good-hearted and good-natured as himself. They had to be small-minded, petty and self-serving oppositionists for all that was Good and Decent, and clearly only Conservatism could lead men to the Dark Side of Totalitarianism. In real fact, both sides have done ill for that cause, in equal amounts and largely with similar results.

So there are some markedly inappropriate contrasts in R’s behavior. He’s probably not a rape victim for reasons suggested, even though he exhibits certain other characteristics of it, and he’s not a particularly good representative of The Right, being a fanatical believer in conspiracy theories (suggesting stupidity) while clearly not being stupid from his capacity to think remarkably fast and effectively on his feet.

But..the right wing nutcase is basically the good guy in Watchmen; he’s the one with compassion. It’s the liberal one worlder who’s the villain.