The monk Tao-hsin was walking in the forest with the sage Fa-yung, who lived alone in the temple on Mount Niu-t’ou, and was so holy that the birds used to bring him offerings of flowers. As the two men were walking, the roar of a wild animal sounded nearby, making Tao-hsin jump frightfully. Fa-yung said, “I see it is still with you!” (attachment to the Earthly illusion). Later on, the two were sitting on two stones next to the temple when Fa-yung went inside to fetch the tea. While he was gone, Tao-hsin wrote the Chinese character for Buddha on the rock where Fa-yung had been sitting. When Fa-yung returned to sit down again, he saw the sacred Name written there and hesitated to sit. “I see,” said Tao-hsin, “it is still with you!” And thus Fa-yung became fully awakened…and the birds brought flowers no more.

__________________

The thing I first noticed about John Porcellino’s short comic, “Christmas Eve” is the breathing.

Because of the simplicity of his style — unvaried line weights, the lack of shading — the bulbous breath hanging in the air is as solid as everything else around it. It could be a distended snow flake, or some sort of alien critter curiously contemplating the (no more or less weighty) human nose. In that third panel, it even has an oddly solid sound effect appended to it — the “klump” is probably supposed to be a car door closing, but it could just as easily be the sound of the tadpole-like-breath bumping up against the panel border. Snow, air, beard-stubble, panel gutter — flesh or vapor, diegetic or un, everything exists in the same flat, empty whiteness, teetering on that thin line between something and nothing.

“Christmas Eve” wanders or drifts back and forth across that line repeatedly. The shapeless blob of breath seems, in that bottom left panel, to actually become the human figure, or the human figure becomes it. Breath out, and breath is gone; breath in and breath is you, breath out and the breath is gone. The self is lost, and found, and lost…or possibly found and lost and found. Drawing is breathing is creation, as long as what’s created is almost indistinguishable from nothing being created, or from nothing being erased.

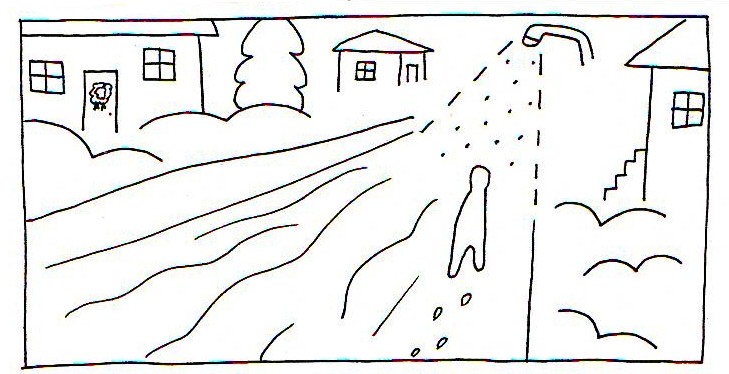

Domingos Isabelinho highlighted this drawing in an earlier post, and it’s still my favorite in the comic; I love the way the lampost just ends, as if Porcellino got tired of drawing it…and the way the snow looks like its embodied light, falling in grainy dots only a little smaller than the footprints below. I think the wavery lines in the middle are supposed to be drifts of snow…but they also read as the lamplight, so what you see and how you see it, perception and perceived, merge into one.

On the penultimate page of the six page story, Porcellino writes the first words of the story: “I don’t want to be alive anymore”. At first I took this as a melodramatic suicide wish, which was irritating…and also seemed to clash with the comics gentle, almost devotional quiet. Thinking about it, though, it seems like it’s less a wish for death than a statement about his relationship to life. Wanting floats off like breath — or maybe the self is the breath that leaves wanting behind. In either case, what goes is desire and what’s left is the self as a kind of gift, that returns after being let go.

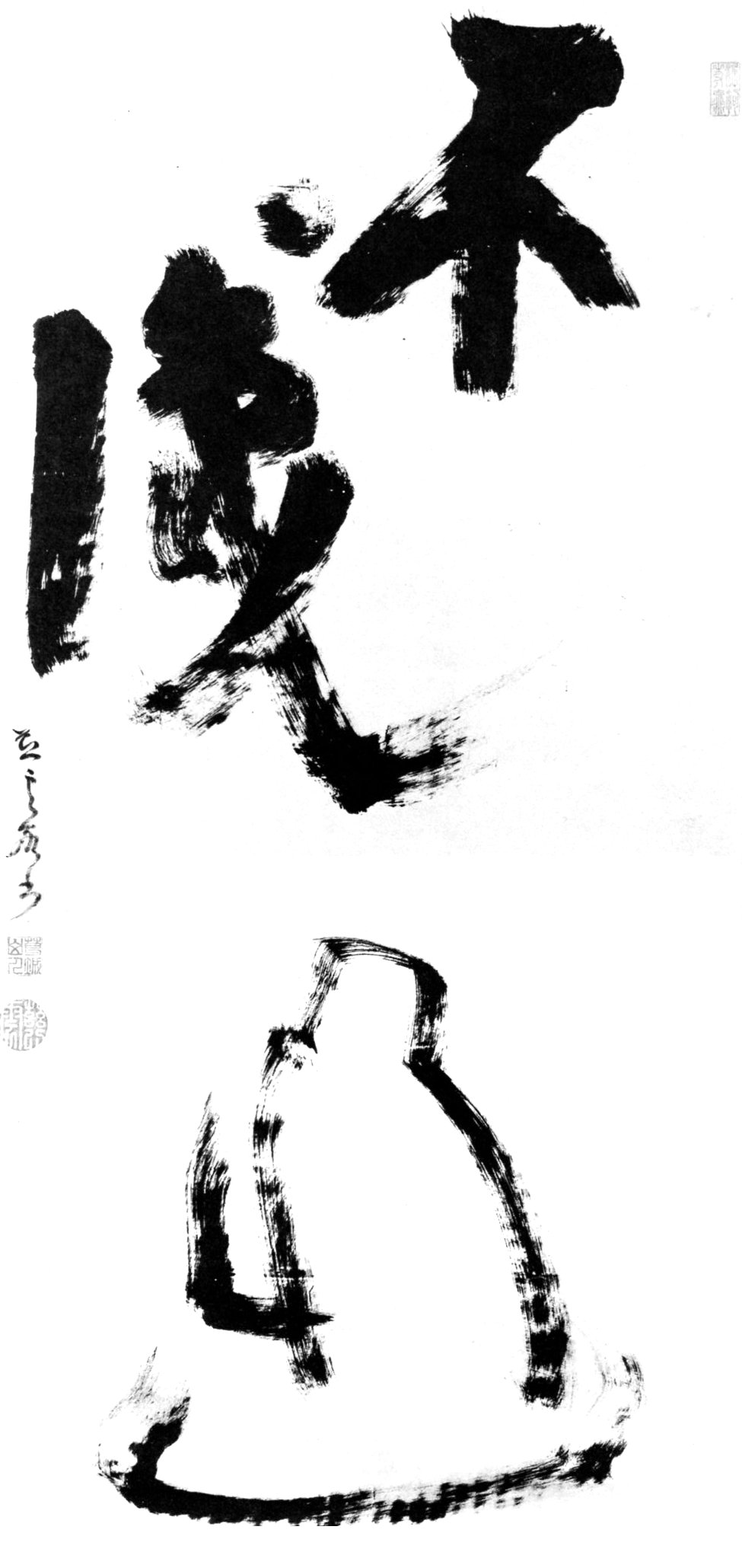

Porcellino seems, with probable intent, to be teetering on the verge of Zen. His wavery outline figures even recall Zen calligraphy, like this drawing by Buddhist priest Jiun Onko.

I’m not sure the comparison necessarily redounds to Porcellino’s credit, unfortunately. Onko’s brush strokes provide a dramatic, intense sense of creation as process which Porcellino’s figures can’t approach, for one thing. And, perhaps more importantly, the single image, summoning something out of nothing, with that one calligraphic statement (which means “Not Know”) seems to resonate much more powerfully, and simultaneously more subtly, than Porcellino’s short but still somehow too long narrative. Really, everything Porcellino had to say is on that first page, or in that image with the lamp. When he gets to the end, and we’re seeing man-looking-at-clouds we start to verge on treacly transcendence and Hollywood clichés. The moment’s too big and too small at the same time, the impetus for narrative closure and meaning overwhelming the earlier pages’ careful not-knowing.

On the other hand, though…there is something very Zen about art that fails in being Zen. Onko’s drawing is almost too good. I think it’s arguably one of the greatest comics ever, actually, but the very greatness perhaps makes it less Zen-like — it’s so holy that the birds flock around it.

Porcellino, on the other hand, flirts with greatness, but ends instead with comfortable banality. It is just a typical story about taking a walk on Christmas Eve, after all. The breath is just breath, the light is just light. There’s nothing special, and the blank space at the bottom of the last page is just there because Porcellino didn’t have enough story to fill it.

______________

The Snow Man

Wallace StevensOne must have a mind of winter

To regard the frost and the boughs

Of the pine-trees crusted with snow;And have been cold a long time

To behold the junipers shagged with ice,

The spruces rough in the distant glitterOf the January sun; and not to think

Of any misery in the sound of the wind,

In the sound of a few leaves,Which is the sound of the land

Full of the same wind

That is blowing in the same bare placeFor the listener, who listens in the snow,

And, nothing himself, beholds

Nothing that is not there and the nothing that is.

Great post, Noah. I’ll read it again later and maybe have some better comments, but…

If Porcellino is not explicitly referencing Zen, he could be subconsciously, as he does practice Zen and has done a bunch of comics about Zen masters/koans.

Give the guy a bit of credit. The blank space seems to naturally follow increasingly simplified figures/forms, and is (presumably) supposed to present a white out, snow, emptiness etc. thus recalling the first words of the story (“I don’t want to be alive anymore.”). So it’s there for a purpose. Which still doesn’t make it genius level comics but not as hopeless as you make it out to be. I think there’s something to be said for varying brush strokes in this kind of minimalistic cartooning, but the straightened forms in this instance probably convey the right atmosphere. The comic isn’t exactly redolent of vigor and life.

Thanks Derik!

That Porcellino practices Zen surprises me not even a little bit.

Hey Suat. I think you’re misreading me somewhat? I like the comic quite a bit, though I have some ambivalence. When I said that the blank space was unintentional, I was (perhaps too subtly) pointing out that the unintentionality is (probably) intentional.

It’s deliberately casual or casually deliberate. I think just running out of space is thematic — everything is fading into nothing anyway.

I don’t exactly agree that it’s not full of vigor and life. It’s a very joyful comic, in its blank zen way.

But joy doesn’t have to be associated with vigor and liveliness right? It’s a minimalist comic but I think you’re right in thinking that there’s still too much going on to convey that impression you get from a traditional zen painting. Which might explain what is actually going on here – Porcellino’s use of comics narrative to show the gradual achievement of satori (not merely the endpoint which is what you get with your favorite Juin Onko brush painting). The turning point in the story might be the street lamp scene you like (but I’m basing this purely on the pages you’ve shown).

I like Wallace Stevens when he’s overflowing anf pagan more than when he’s Buddhistically comparing absences, I think. There’s a nostalgia for Actual Reality coupled to nihilism that has resulted in the irritating twee sentimentality of late modernism like John Porcelino. Minimalism should be epic, not poignant. Not dismissing all the redeeming qualities of twee culture, but its romantic sublime really needs to be way less rpressed in many instances.

Sorry for ttyyppooss.

That’s funny; I was thinking you might not really be into this, Bert.

I think “twee” and “sentimental” are both definitely fair cops re: Porcellino (or at least this story.) On the other hand….like I said, the smaller than life quality of it is I think affecting. And I think there’s a pretension to eschewing sentimentality too — and even a nostalgia for actual reality in doing so.

Plus…that lamppost drawing just makes me happy.

Bigger tahn life can be maudlin, but is rarely hampered hyper-self-awareness, whereas maller than life can be every bit as maudlin in its preciousness and really needs to be oppressive and uncanny (Museum of Jurassic Technology style) to make up for it. Epic art gets faulted for leaving nothing to the imagination, but twee art forecloses the possibility of anything imaginary. Reality as portrayed in a navel-sized snowglobe.

Sorry– I’ll try again. Rushed at work but fuck it.

Bigger than life can be maudlin, but is rarely hampered by hyper-self-awareness, whereas smaller than life can be every bit as maudlin in its preciousness and really needs to be oppressive and uncanny (Museum of Jurassic Technology style) to make up for it. Epic art gets faulted for leaving nothing to the imagination, but twee art forecloses the possibility of anything imaginary. Reality as portrayed in a navel-sized snowglobe.

You think Porcellino is claustrophobic? That’s really not my experience of it….

I’d say that actually bigger than life — grand gestures, giant statements — is often extremely self aware. Watchmen would be an example…or Anselm Kiefer. Smaller than life seems like (in Porcellino, anyway) to allow for questions about intentionality and the amount of space the author is trying to fill (or not trying to fill.)

I mean, I like and dislike examples of both. Jeff Brown is somebody who is doing the half-assed punk rock thing which is twee and precious and uses that as an excuse not to be or do anything. Punk rock and Zen have some things in common, but they’re not exactly the same. Porcellino’s not trying is idiosyncratic and evocative…like Philip K. Dick, to some extent.

This comic doesn’t seem solipsistic to me…or only in the way in which zen is solipsistic, which is fairly complex and interesting. The fact that it is so obviously Zen inspired in itself is a move outside the self, right? He’s interacting with a cosmology. You might not like that cosmology, but it’s not located (solely) in his navel.

“Punk rock and Zen have some things in common, but they’re not exactly the same.”

Brad Warner has written about this quite a bit.

Twee must mean something different than I think, cause I don’t see Porcellino as Twee at all (Jeffrey Brown on the other hand, I can see as often twee).

Well…Porcellino is precious at least to some extent. You could put Christmas Eve to a Donovan soundtrack, and it would work okay….

What has Warner said about the connection between punk and zen? Can you summarize?

Donovan is an interesting case. Like Wallace Stevens I consider him a culture hero because at bottom I think he represents abundance rather than economy, even if he does sing about monks on misty mountains. Alan Moore and Anselm Kiefer are postmodern, Alan Moore is self-referential, but that doesn’t mean he’s obliterating himself because he’s worried about being tacky– far from it.

Claustrophobia and uncanny proximity exists in lots of great stuff– Dick, sure, Kafka, maybe Bartok, maybe Twin Peaks– but the oppressive smallness of the context or the form suggests a vast uncharted zone, rather than having ineffability drizzled over everything like negative-space ketchup.

Smug, I’m trying to say.

See…Porcellino doesn’t exactly seem smug to me either, at least not in that piece. Nor does it seem oppressively small or mundane, the way autobio comics often can. It’s zen; it’s about the cosmos in the mundane and the mundane in the cosmos, which can be a little treacly, maybe, but isn’t mired in the aesthetics of the quotidian. It’s not trying to be ugly, or validated by ugliness; it’s schematic, but in the service of the sublime, not in the service of not giving a crap.

I mean, I do have reservations…but I definitely don’t have the same problems with it that you seem to.

It didn’t insult my heritage or anything (perhaps it over-recalls my WASP heritage in fact). I’m not saying it’s sloppy or amateur or tasteless or even banal. It represents very little of what makes pulpy comics unbearable. And yet– this is a guy who makes comics based on “Walden,” for Henry’s sake. Pretension can be great– I love Led Zeppelin, I love Morrissey, I even find Jim Morrison entertaining by turns. But Porcellino’s pretension is an cold –not bleak, just ungenerous– pretension. Much like Matisse, who I just found out did a 7-Up ad. It’s not all hipsters that bother me, or all advertising, but hipster advertising is vile. Not that Porcellino has advertised anything other than himself. but his very design-savvy brand-ability makes me itch.

I did notice being accused of being a Zen hater, by the way. Distrusting Western cultural appropriations of Zen is hardly the same thing as hating Zen. I was not accused of hating punk, but it’s also a similarly mixed bag– as are most value systems. But punk values the pariah and the runt, which I appreciate, and Zen values annihilation and focus, which I also value highly, perhaps as means rather than ends.

I didn’t call you a zen hater! I suggested that you might dislike the cosmology because I thought you might. I’m not actually sure what your take on zen is at the moment…though valuing annihilation and focus as means rather than ends isn’t exactly zen….

You think Porcellino’s comic looks like advertising? Really? Again, you’re just seeing something there that I’m not….

The thing about it that seems advertising like isn’t the design or the empty drawings but the transcendence at the end…like I said, that’s a little Hollywood for me….

It’s a New Yorker illustration turned into an existential vignette, is what it really is.

Warner has written several books on Zen, referencing Punk a lot (he seems to have been in a hardcore band in the eighties–basically coming from the same place as John P.) I read his first one, Hardcore Zen. Hard to summarize (or, to be honest, to recall at this moment), except that he says, Zen is like Punk, Punk is like Zen. I didn’t find it the most satisfying book of Zen popularization. Not much there there. He’s a bit controversial in the online Zen community, a lot of people don’t like his style. You may want to look up Jundo Cohen–a student of the same teacher, who has occasionally clashed with Warner.

It’s also worth noting that John practices Soto Zen. All the great art, Jiun included, comes from Rinzai. Soto is pretty poor, artwise–and even calligraphy-wise. But John’s art actually makes much more sense if you think of it in the context of Soto, not just Zen in general.

Also–what Zen cosmology? Does Zen have a cosmology? I’m not sure what that means.

I know that I wrote a stumbling about this Porcellino story, but I didn’t want to spoil it to everyone. Thanks for doing that for me, Noah! I definitely loved your “breath” comment, so: great post!

Unfortunately I can’t comment right now because I’m practically out the door, but a New Yorker illustration turned into an existential vignette sounds good to me. I’ve nothing against New Yorker illos per se (some are good, some aren’t, right?) and I love well done existential vignettes.

FWIW, here’s a Zen discussion forum about Warner:

http://www.zenforuminternational.org/viewtopic.php?f=63&t=7660

By the time I read “Hardcore Zen,” I knew enough about Zen to not get much at all out of it–but, to be fair, I can imagine some kid in high school discovering it, for whom it then becomes the most important book ever.

Also FWIW, here’s Warner’s blog: http://hardcorezen.blogspot.com/

Thanks for all the links! I will try to get to them….

I think an anti-cosmology is still a cosmology.

Not sure how anyone could find Matisse cold, ungenerous, or pretentious:

http://www.joanannlansberry.com/fotoart/artic/matisse-nice.jpg

But I’m pretty sure we can agree that Matisse did NOT do a 7-Up advertisement:

http://www.flickr.com/photos/30559980@N07/5508316972/

Still haven’t had a chance to reread this, but…

Warner’s Sit Down and Shut Up (and his subsequent books) is much better than Hardcore Zen which suffers a bit from being a first book and perhaps from trying too hard on the punk/zen thing. I’ve really enjoyed his books, and it’s lead me to a number of other Zen thinkers/writers.

A big part of his zen/punk comparison is about questioning authority. A lot of the “controversies” around him relate to his criticisms of various “masters” and issues of easy answer and unquestioned authority.

And some people just don’t like his style, which admittedly I find annoying at times.

Not Matisse, you’re right. But such a seamless appropriation.

Late on this, but going back to the article and then the comments…

“Wanting floats off like breath — or maybe the self is the breath that leaves wanting behind. In either case, what goes is desire and what’s left is the self as a kind of gift, that returns after being let go.”

That’s very well said.

One thing I noticed this time reading, relating back to the line between something and nothing, are the top two panels on page four. Both have the same background, a little double-humped curve that could be a cloud but more likely is some kind of foliage. The first panel shows Porcellino, the second doesn’t. He’s there and then he’s not.

“The moment’s too big and too small at the same time…”

“The breath is just breath, the light is just light. There’s nothing special…”

Both of these statements (and I’m not clear if you’re stating them as strikes against the work or for it…) I think point back to the Zen elements of the piece. The moment is both big and small, any bit of realization (I can’t say “enlightenment”) like that, is both something big–the thought/idea/moment, the potential for change–and something small–it’s “just” clouds, just a moment, just the world being the world.

“You could put Christmas Eve to a Donovan soundtrack, and it would work okay…”

I guess, but I think it would be the act of adding the soundtrack that would make it “twee.”

“(and I’m not clear if you’re stating them as strikes against the work or for it…)”

Both, I think…though probably more positive than negative.