About a year ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration unveiled a series of nine large cigarette package labels that add vivid images to existing text-only warnings about the dangers of smoking. These new “enhanced warning labels” include pictures of corpses, a diseased mouth, lungs, and throat, and infants threatened by second-hand smoke followed by phrases such as “Cigarettes cause cancer” or “Smoking can kill you” and an 800 number for help.

About a year ago, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration unveiled a series of nine large cigarette package labels that add vivid images to existing text-only warnings about the dangers of smoking. These new “enhanced warning labels” include pictures of corpses, a diseased mouth, lungs, and throat, and infants threatened by second-hand smoke followed by phrases such as “Cigarettes cause cancer” or “Smoking can kill you” and an 800 number for help.

The labeling system, part of the Family Smoking Preventing and Tobacco Control Act of 2009, was to go into effect this September until a group of tobacco companies sued to block the requirement. While one federal judge ruled earlier this year that the warnings violated the free speech of the cigarette makers and granted a preliminary injunction, an appeals court in a related case disagreed, making it likely that the issue will end up before the U.S. Supreme Court.

I was listening to a report about the ongoing case on NPR two weeks ago and I was particularly struck by the kind of language that the judges, federal officials, anti-smoking advocates, and constitutional experts used to describe the images and their impact on consumers.

“It’s going beyond I think what is necessary,” says David Hudson, a scholar at the First Amendment Center in Nashville, Tenn. “It’s just so in your face, so graphic, these images — it’s just simply too much.”

[…]

“The picture of somebody that is dying from tobacco can be an accurate representation of the health effects of smoking, even if it evokes an emotional reaction,” [Matt Myers, from the Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids] says. (NPR)

How do we go about weighing what is accurate and emotional when it comes to the information that these images convey? And how do we decode a sight that can’t be put into words because it’s just simply too much? I can’t help but think that the Supreme Court should call Charles Hatfield to testify about these very questions, but until then…it might be useful to consider how comics studies might benefit from a discussion about cigarette warning labels.

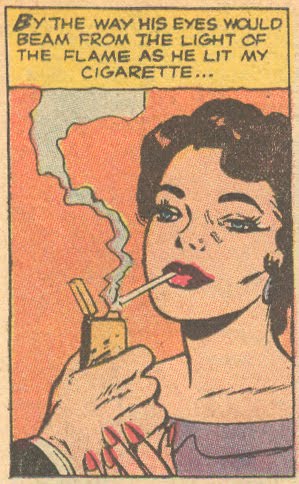

For one thing, the issue allows us to think more carefully about how assumed notions of perceived and received images operate in practice. The news reports about the labels consistently highlight public officials, corporations, and advocacy groups in the act of measuring qualitative differences between this:

And this:

Confronted with the new labels, these sound bites and legal opinions appear to revolve around concerns over visibility, accuracy, and provocation: how we see the images, how we interpret them,and how they make us feel.

On Visibility: Thomas Glynn with the American Cancer Society refers to the old labels as “invisible” and according to CNN, “people have become immune and don’t really ‘see’ them any more.” Other FDA officials express the hope that more visible warnings might counter the tobacco’s industry’s well-funded efforts to downplay the harmful effects of cigarette addiction through colorful ads of their own. The concerns on both sides of the issue bring to mind a number of strategies that comic book writers and artists deploy to maintain the attention of readers and to convey subtle nuances of meaning. But as the public becomes exposed to the cigarette warnings, couldn’t even the novelty of the increasingly graphic portrayals reach a new tolerance threshold?

On Accuracy:In deciding matters of constitutional freedom, the district court judge that blocked the labels was less concerned with matters of perception and sustained attention, and more troubled by the way the images appeared to cross the line between “information” and “advocacy.” Judge Richard Leon wrote that, “the Government fails to convey any factual information supported by evidence about the actual health consequences of smoking through its use of these graphic images.” The image of a body on an autopsy table, meant to represent the 443,000 deaths caused by tobacco, left too much room for interpretation, claimed the judge. (NPR) One wonders if a similar logic could be applied to the verb cause in the text-only label that declares: “Smoking causes lung cancer, heart disease…” Could we scrutinize the different variables and contingencies that inform the FDA’s word choice here, or do words discourage us from making the kind of assumptions that images do?

On Provocation: The tobacco companies defend their legal right to sell cigarettes by arguing that the government labels actually go beyond advocacy to shame. While the word emphysema objectively informs, the image of a lung, brown and marbled with the disease, repulses in ways that project negatively upon the consumer. Consider the statement from cigarette maker R.J. Reynolds:

“The anti-smoking message is not intended to provide information that smokers and potential smokers can consider rationally in weighing the risks and perceived benefits from smoking. Rather, it plainly conveys — through graphic images and designs intended to elicit loathing, disgust, and repulsion — the government’s viewpoint that the risks associated with smoking cigarettes outweigh the pleasure that smokers derive from them and, therefore, that no one should use these lawful products.” (CNN)

Interestingly enough, the appeals court panel that rejected this view also commented on the impact of the graphics, “finding that the fact that the specific images might trigger disgust does not make the requirement unconstitutional” (Huffington Post). I can’t help but think of the “severed head exchange” between EC Comics publisher Bill Gaines and Senator Kefauver in the 1954 Senate Hearings on Juvenile Delinquency when I read about judicial decisions that distinguish between perceived levels of disgust.

Ultimately, each group brings a different set of investments to the debate over the cigarette labels in ways that reveal fascinating insight into how words and images are privileged. Ironically, the fact that the new labels contain both pictures and text is often overlooked; each warning is dependent on the other, as well as the packaging, to convey the risks and pleasures of the product inside. (It is also worth noting that not all the new labels are photographs, at least one is a comic art illustration of a premature infant.) How does the interplay of visual and verbal elements in comics help us to think through the debate over enhanced cigarette warning labels?

___________

Cross posted at “Pencil Page Page.” Comics image above via “Sequential Crush.”

A very interesting article.

Comics used to exalt smoking as something cool and virile. At Marvel Comics, such characters as Nick Fury, Wolverine, the Thing, and Howard the Duck used to smoke like chimneys. Now they’re all ‘on the patch’, apparently through the decision of editor Joe Quesada, though the scripter T.Casey Brennan had been campaigning against tobacco in comics for years.

I’m wondering if Lacan might be a useful way to think about this at all? (Probably not, but what the hey.) In that language is in the symbolic and images are in the imaginary…and the imaginary is where you have the mirror stage, where children/people (mis)recognize themselves. So when you use images you’re showing people a (mis)reflection of themselves, which is both more visceral and open to charges of being false (since all recognitions are misrecognitions, etc.)

Not that anyone wants to (or should!) look to Lacan for legal guidance…

There was one scene where Wolverine is smoking a cigar and Kitty takes a puff and gets sick and Wolverine explains that his healing factor means he can smoke without any of the negative consequences. Which I suppose was a kind of anti-smoking message….

And Marjane Satrape is a somewhat militant anti-anti-smoking campaigner. She claims that being anti-smoking is part of our notion of puritan anti-pleasure.

Which I find fairly annoying as someone whose wife can have fairly intense asthma attacks caused by exposure to second hand smoke. But I suppose she’s coming out of her experiences in Iran, where control is usually defined in terms of denying pleasure. I guess it can be a little tricky to make the leap to realizing that in capitalist contexts pleasure is an instrument of control, not necessarily a rebellion against it.

Sure, just ask Aldous Huxley!

Noah, I’ve not taken the time that I should to explore Lacan in relation to comics, but I think the idea you raise about “language is in the symbolic and images are in the imaginary” is incredibly useful here and can help to speak to the uneasiness that critics have expressed about why/how viewers will identify themselves with the diseased patients (something the FDA obviously welcomes). Do you know of any other comics theorists who develop this kind of Lacanian approach further?

The Sequential Crush blog post (linked at the end) really shows how much times have changed! Particularly hilarious is the scene with the doctor offering the patient a cigarette…!

Qiana, my impression is that there’s not a ton of Lacanian analysis of comics. I’ve done a little bit here and there and also here, but I’m really just a dilettante. Caroline Small is really the expert, but I don’t know that she’s explicitly used Lacan to talk about comics (though check out the comments here.)

If you’re thinking of trying to figure out Lacan, I think Jane Gallop’s “Reading Lacan” is a great book; kind of incredibly accessible, all things considered, and really smart and entertaining. She doesn’t talk about comics, of course….

Awesome, thank you!

Yes, images can drive a subject home in a much more visceral and explicit way than text alone. Images have a profound impact on the reader/viewer, which puts the lie to writers who claim to be the primary creators in comics. I hope cigarette packages DO have these images on them in future and I think cigarettes should be banned—tobacco companies should be put out of business completely. If I hadn’t smoked, I wouldn’t have had the heart attack I suffered a little over a month ago. Yes, it was my own fault as well, but the tobacco companies are murderous drug dealers.

Prohibition is probably a bad idea for cigarettes as for alcohol or any recreational drug. But more explicit warning labels can’t hurt.

I fail to see why we have our prisons filled with people of color for possession of weed (other than that they form a slave labor force for the privatized for-profit U.S. prison system) while the drug dealing scumbags of the tobacco industry are free to sell something known to kill many many people each year. It’s not recreational, it is an addictive drug.

Well, if you outlawed tobacco, you’d have a black market and criminal violence, same as outlawing cocaine or alcohol. Regulating it with warning labels or what have you just seems like a better option to me.

But yes, of course, outlawing marijuana — which is not addictive, has actual medicinal benefits, and which is overall a much, much safer drug than alcohol or nicotine — is insane.

Note that cocaine is not legal and that it would be insane to legalize it, because people on cocaine behave like maniacs. Yes, there’s an illegal trade in it and people for to jail for having or dealing it but that is for specific reasons. Pot is not nearly so virulent, though it tends to make people more stupid and I do not advocate its use by kids. So many people die from tobacco use and its toll on the population and drain on health resources is such that it seems obvious that it is something that should not be approved by society.

People on alcohol are violent and dangerous too….

Interestingly, while it may be said that pot is not addictive, it is habit forming and particularly in the case of kids who smoke blunts, they become addicted, but to the tobacco component which is the tobacco leaves that cigars are rolled in, i.e. they empty the guts of cigars to be replaced with weed. They inhale the smoke from this much more deeply than any cigar smoker would and so, in the absence of any studies, I believe we will see many adverse health affects in coming years from this practice.

A glass or two of wine is good for you. I can’t say the same for straight up booze. Though, at least if you drink the better stuff and don’t mix you don’t get such a bad hangover. There’s really nothing to be said for beer, the drinkers of which apparently believe they aren’t really drinkers, I’ve known quite a few that consume a sixpack or more per night but don’t think they have a drinking problem, ha ha.

I was eliminated from a jury pool concerning a drug deal because I stated my view that all drugs should be legal. I guess you can use that as a tactic if you don’t want to serve. Anyway, I’ve never felt much sympathy for wanting to control the behavior of others because you can’t handle something — particularly when such control leads to the evils we currently have with the drug trade.

Also, I used to enjoy an occasional clove cigarette until R.J. Reynolds supported a bill that made “flavored cigarettes” illegal. They appealed to children, it was argued. … Except methols, which coincidentally are made by R.J. Reynolds.

True enough…it’s easy for me to get on my high horse since I don’t drink, or smoke pot or cigarettes now any more. But I’m not even going near saying booze should be illegal and I’m all for decriminalizing pot, but I don’t think pot, booze, coke, dope, cigs or any other drugs should be promoted to children and I don’t think cigarettes are good for anyone but the scum profiting by them hugely. When our slimy 1%er mayor Bloomberg limited smoking indoors I didn’t really complain because y’know what? I smoked less…it made it harder. He keeps trying to do more stuff like that that could be seen by some as intrusive and I think he’s a jerk in many ways…but smoking sucks. Pretty hard to defend the death sticks.