Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of student papers from Phillip Troutman’s class at George Washington University focusing on comics form in relation to Scott McCloud’s theories. For more information on the assignment, see Phillip’s introduction here.

__________________

Scott McCloud is quick to introduce the concept of closure as the defining aspect of comics and is nearly as quick to locate it as existing in “the gutter”, the blank space between the panels in comics. This is a useful shorthand, but as he further develops these ideas it becomes clear that closure is actually a continuous involuntary act on the part of the reader that does not rely on the panel or gutter at all. In fact, closure occurs within panels quite frequently and is the result of time being represented, usually implied by sound or motion. As McCloud explains, in a purely visual medium like comics, time, or the motion and sound that implies time, can only be represented through the space on the page. In comics, space and time are the same. This reduces the panel and its negative space, the gutter, to icons that indicate that time and space is being divided. In effect, the panel and gutter have less to do with the actual process of closure, that is, perceiving the whole from parts, and more to do with indicating what is a part.

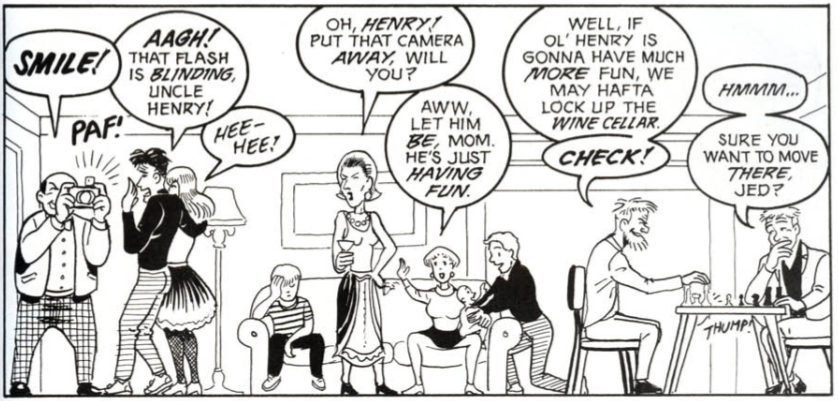

So as this image from McCloud’s Understanding Comics demonstrates, closure can occur without the use of intervening gutters to indicate the passage of time. As McCloud explains, the movement of our eye across the page is enough for us to understand that time is passing and to make sense of what is happening. Gutters are not necessary. This leads me to conclude that it is the act of scanning the page that generates closure. By scanning I mean the almost involuntary movement of our eyes across the page and the unconscious synthesis of the images on the page into a narrative.

Consider the polyptych, a technique used in Guardians of the Kingdom by Tom Gauld. A polyptych in the comics world is where “a moving figure or figures is imposed over a continuous background” (McCloud pg 115). The polyptych provides an example of closure occurring in one setting, likely with one subject or a small group acting or talking (that is, providing sound or motion to imply time and generate closure), but it is a technique that requires the use of panels as an organizational framework, despite the fact that all the closure-generating action of a character occurring within one setting could only logically be explained as a passage of time. Otherwise it would appear as the sudden multiplication of one character into many copies, something I think it is safe to say could easily be ruled out through context.

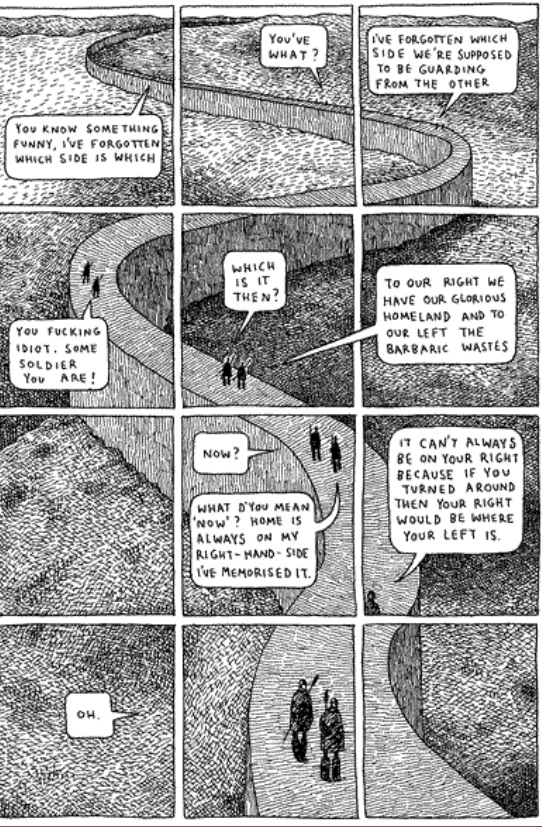

For example, this polyptych from Gauld’s aforementioned work uses one scene and only two characters, both moving and speaking and thereby implying the passage of time. It also has a very basic set of panels dividing the image which helps to emphasize and clarify the passage of time. The panels help to organize the image on the page, but they are not necessary to understand the image, which is to say, to generate closure. If there is some doubt about this assertion, imagine the page without the panels. Although it might be momentarily confusing, reading the whole page would provide the necessary context for closure to occur. In fact, in this particular instance, even that much probably wouldn’t be necessary, as the reader would be aware that there are only two characters in this book. Nonetheless, the panels do help and McCloud’s characterization of them as icons for the division of time seems to make sense, although they might be more accurately described as indices. An icon bears a visual similarity to the thing it represents, whereas an index does not necessarily resemble anything, but indicates that what it represents is occurring. As panels and gutters can’t be said to visually resemble the passage of time, but instead indicate that it is happening, they are indices.

Why, if they are not necessary, do we see panels and gutters so often in comics? The answer is that while they are not necessary for closure, they are necessary for comics as a format. They help us to organize the page and are the author’s means of steering our scanning of the images. Imagine, once more, the page above without panels. But this time imagine that it is huge, far larger than any book would allow, so large that it would take some time to scan the whole image from top to bottom. In that case, the winding wall and real time needed to scan the page would provide all the indication of the passage

of time necessary. Closure would certainly occur without the panels. In essence, panels are not necessary for closure; they are an accident of the format that has been developed by authors as a means of directing the process of closure, thereby shaping the meaning we draw from the comic.

There is further evidence to suggest that while closure doesn’t strictly require panels, comics do. More broadly, any visual narrative art requires panels and if those panels are not explicitly drawn, they are implied. The Bayeux tapestry, an 11th century embroidery depicting William the Conqueror’s successful invasion of England, although clearly not a comic in the modern form, works just like one. It combines images, definitively on the iconic side of the spectrum, and words to tell a story. It scans from left to right and is

broken down into a number of scenes, although none are explicitly numbered or

otherwise differentiated. But the fact remains that the panels are implied. The need for organization in the images was still present and panels, or in this case scenes, are apparently the instinctual way to depict this.

It is my contention that closure occurs constantly through our scanning of the images and the involuntary creation of meaning out of the juxtaposed images on the page. The panels and their negative space, the gutters, act only as a way of organizing these images for, no doubt according to the author, more meaningful scanning. Further, I would argue that panels are actually just a formalization of our natural scanning and is due mostly to the physical format that comics take. The fact that comics generally come in books, that

is on pages read left to right, top to bottom, has necessitated the use of panels. Specifically it solves the problem of moving down the page, something the Bayeux tapestry doesn’t have to deal with and consequently didn’t create a system like explicit panels to direct the reader. I do not disagree with McCloud that “closure is comics”, indeed any visual narrative must have closure because that’s how we make sense of them. And I would go farther, perhaps, than McCloud by stating that comics are panels, whether those panels are implied or explicit, because the format demands it. But, as I believe I have shown, there is no transitive property at work here; panels and their gutters are comics, comics is closure, but panels and gutters are not closure.

This is a really smart and well-written piece, Travis.

I think you’re right that panels are markers of comicness rather than necessary mechanisms of closure. I don’t quite buy the idea that panels are a *necessary* mark of comicness though — that is, I don’t think it’s right to say that there are always panels, even when you don’t see them. I don’t think the Bayeux tapestry is organized via phantom panels, for example. That seems needlessly totalizing, as well as kind of ahistorical.

I’d say instead that there doesn’t need to be one marker of comicness, or one way that comics are organized. There’s a whole bunch of historical ways the form is defined (which includes panels, speech bubbles, multiple images forming a narrative, etc.) and they combine in different ways to let a reader know that item x is or is not a comic. That’s sort of sloppy, but I think more accurate than McCloud’s more rigid approach to classification.

This is an impressively lucid article, Travis. I often despair at the repetitive, circular nonsense that constitutes the majority of academic work on comics (at doctorate level, let alone undergrad!) so it’s a real pleasure to read such a concise essay, presenting a single original idea so clearly. More like this please!

Yes; a truly excellent and well-thought-out piece of writing!

—————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

… I don’t think it’s right to say that there are always panels, even when you don’t see them. I don’t think the Bayeux tapestry is organized via phantom panels, for example…

—————————-

Whether we enlarge the definition of panels or come up with another term entirely, there certainly is a phenomenon at work whereby we mentally divide a single scene (that Scott McCloud panel, the Bayeux tapestry, Codex Nuttall ( http://ignorantisimo.free.fr/CELA/docs/mirrorMyHarvardRabasa/Rabasa134/visual%20archive/codex%20nuttall/nuttall.lord_12_wind.jpg *) into what are clearly intended as “narrative units.”

Call it “narrative or temporal bracketing,” perhaps?

*More at http://ignorantisimo.free.fr/CELA/docs/mirrorMyHarvardRabasa/Rabasa134/visual%20archive/codex%20nuttall/

Although you claim that gutters are not necessary for closure, I think that without them, readers would be less likely to follow along in the story. Readers could lose focus on the plot and possibly fall into a web of mindless scanning of the page with no direction as where to go or what to look at first. Gutters aid the readers’ ability to read more easily and rapidly.

You make a valid claim but I don’t agree with your understanding of McCloud’s initial point. He simply introduces the idea that closure exists in the gutter. I feel as though you are exaggerating his words a bit and implying that this is the idea “comics can only have closure if they have a gutter.” McCloud may have not meant to make this argument at all. Instead, he may have been saying the gutter is one place to find closure, not the only place.

On that note, McCloud may have pointed out the fact that since comics are not books, they do require some form of breakage. It would certainly be difficult to chronologically understand a scene if it is just one large picture.

There are quite a few examples of comics without borders, and many ways to create chronological understanding of scenes within a single image.

Here for example; or consider the examples here.

I’ve always thought the “narrative units” of Rembrandt’s “The Blinding of Samson” would translate well into comics.

The “all in one piece” original: http://uploads7.wikipaintings.org/images/rembrandt/the-blinding-of-samson-1636.jpg

The “panelized” version: http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/Blinding_Samson_comic2.jpg

How haunting is that ambiguous look back of Delilah’s! Gloating, fascinated, horrified? “All of the above”?

Needless to say, the online version loses detail like the glistening drop of blood flying out of Samson’s eye; on the other hand, the pathos of his toes clenching in agony as he is stabbed comes across…

I agree with you that gutters are not necessary for the reader to follow along with the story and provide some sort of closure, however I do think that they are very helpful. I believe that they provide little breaks for you to mentally check that you are paying attention to the comic. I think that without them, as other people have commented, it is very easy to mindlessly scan over an image without truly realizing what it going on.

Hey Travis, I do think your crit was well written and concise which made it to the point and enjoyable to read. I see your point and do agree that perhaps McCloud thinks of the closure to be almost like a rule in comics and that panels are necessary for that. But I feel that McCloud’s claims are all somewhat demanding in the sense that he almost makes it sound like comics have to be the way he explains them to be. So I understand your view that panels and gutters don’t have to exist solely as a part of closure, however, they do add to the effect. Whether they are necessary or not will depend on the artist’s personal choice though and I’m sure there are a lot of works which defy these ‘rules’ that McCloud states or don’t follow with the same meaning he provides. But I also simply think that the closure is still aided with the panels and gutters and it makes it fun for most comic readers as it is something we have become used to seeing while reading.

I really enjoyed how you took something so synonymous with comics and questioned the need for its existence. However, I’m not sure I entirely agree with your statement that gutters and panels aren’t necessary for closure. Though I do believe the elimination of panels would work for your given example, I think claiming that closure could still occur in comics in general without that division between scenes it perhaps overgeneralizing.

Travis, I enjoyed reading your piece and it pushed me to look at comics in a new way. Your first visual representation of the comic without panels was enlightening, however, I do think that gutters and panels are necessary. By necessary, I mean the physical existence not the implied. I don’t believe that the gutters and panels are always implied, and that there are comics that are exceptions to your claim.

I truly enjoyed reading your piece. I was truly impressed by the fact that you wrote about something that is present in all comics, yet the average reader does not recognize. When we think of comics, we always envision the panels. Through your work and the examples above, I truly believe in your claim and understand how the panels are simply an organizational aspect of comics. Closure has only to do with the reader and not with the gutters.

This is a very well written piece of work. The organization of your essay definitely helped me understand your claim about comics and their relation to closure and gutters. In the beginning of your essay you state, “In comics, space and time are the same.” I was wondering, is this something McCloud asserts or is this an original idea of yours? Also, I think it could be helpful if you included an image of the Bayeux tapestry in your work, because when you included the other images it really aided me in understanding your claim. I think including this image has the potential to add evidence for your assertions. Once again, this is a really fantastic piece of work.

I really enjoy reading your pice of work about comics. I do agree that the right uses of panle and gutter effect the presentation and the qality of comics. however, it was clear forme that in the polyptych, wich is a work of art composed of several connected panels, Gauld’s example you gave that panel and gutter both are related to closure. and without having these three maine carechrateristeic the timeline and the pasage of the comics is totaly losted and make the comics confusing to reader.another last thing is that also in the same image the consept was indecating a speech of two people or more in the same way but they totaly talking about different things and unclear. and from here the consept plus right sequance,panel or gutter end us with understandable clear comics where both consept related to the art work.

Pingback: The Gutter in The Secret of Kells | ENGL 386 The Graphic Novel

Wonderful thoughts on one element, “the gutter,” of my favorite medium, comics, which distinguishes it’s unique artistic musical storytelling from other storytelling & artistic mediums.

I have felt, thought, since my own beginning to studying Sequential Art, with the help of McClouds work and much else, that substantial narrative influence is in “the gutter,” more clearly now influencing closure. Thanks. What is inherent in negative space (with or without clearly defined lines) is a paradox of opaque “unknown” and a blank canvas of opportunity for audience “interpretation.” Yet there are a plethora of influences offered by author/artist going in and being pulled out of “the gutter.” The inertia of pacing, imagery, text, panel layouts guiding of the eye going in can very greatly the reading and influences going in to a gutter, depending on the individual audience member. Same happens as they are pulled out. Reynolds pulls together many elements at play here.

In my mind there is substantial control still left to the audience to interpret their own closure, because of the gutter and the independence of individual minds. This has helped cultivate fertile ground in the comics community for debate. Helping develop emotionally fueled fans with a apatite for hyperbole and lists. This is despite substation guidance in narrative, aesthetic and philosophical guidance from the Cartoonists. No matter how much detail they put down on paper (to make clear their intended point of view) or how little (to improve the accessibility of a broader audience) the reality is, “the gutter” provides infinite space for the audience to place themselves in control. This control, while informed by the Cartoonist, breeds ownership of the story in the hands of the Audience. Authoring the Audience opportunity to determine closure. The ownership breeds, for good or bad, passion for the characters, place and events.