Editor’s Note: This is part of a series of student papers from Phillip Troutman’s class at George Washington University focusing on comics form in relation to Scott McCloud’s theories. For more information on the assignment, see Phillip’s introduction here.

_______________________

Color remains a question rather than an answer in comics: Some artist’s embrace it, while others continue to ignore it. Whatever its use, color plays an important role in forwarding the message of the artist. Yet such a message is ambiguous. In his analysis Understanding Comics, Scott McCloud notes that color promotes comics by reaching toward reality, making a panel appear to be a much more relatable image to the reader, who lives in a world beyond black and white. Mirroring life itself, which is far from flat, colored images add an extra dimension to the page. But is this the true purpose of color in comics? McCloud suggests otherwise; however, due to the brevity of his designated chapter, he never explains why. Indisputably, comics serve to simplify life, easing the ability to communicate some sort of integral message to the reader. Breaking the fourth wall, color magnifies the author’s claim. Minute tidbits of otherwise unseen details reveal themselves through the additional lens of color.

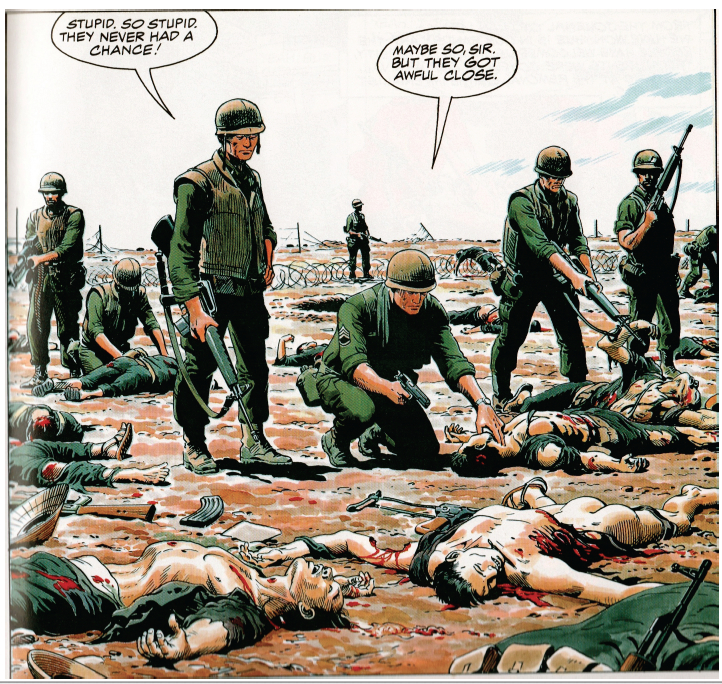

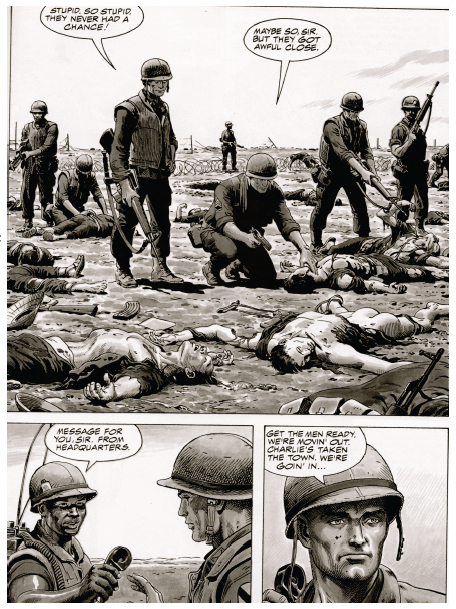

The following image derives from Doug Murray and Russ Heath’s “Hearts and Minds: A Vietnam Love Story.” The panel displays the death and destruction caused by the detonation of a grenade during a battle in the Vietnam War.

Throughout my analysis, I will revisit this image in order to touch upon the overlooked meanings that color specifically reveals.

Color magnifies important details that forward the cartoon’s claim. Though images may appear more realistic, the purpose of color remains for graphics to appear more simplistic. Noting the simplicity of cartoons, McCloud emphasizes that, overall, cartooning is a form of “amplification through simplification” (30). Comics pride themselves in exaggeration, which empowers a point rather than detracts from it. In this sense, color is yet another mouth for exaggeration. Heath’s image exhibits excessive exaggeration due to the use of color. Studying certain features of Heath’s panel, readers must digest uncomfortable truths that the artist is emphasizing. For instance, the two Vietnamese corpses expose gruesome depictions to readers.

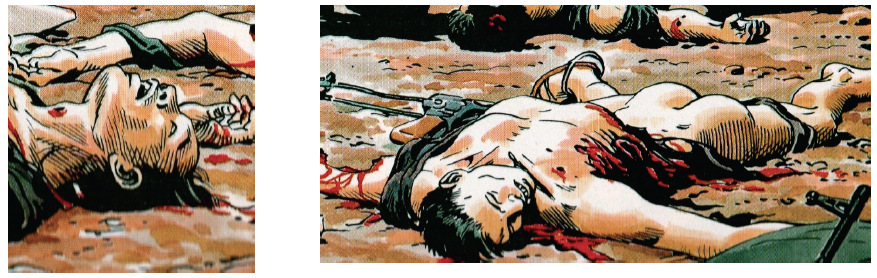

In the first image, color contrasts the white bone protruding from the dead man’s neck from the background. Clean and crisp, this bone appears as though it is out of place. Looking as though it were a plastic piece in the board game Operation, the bone could easily slide back into the dead man’s body. Though, in reality, this bone would be muddled with blood and dirt rather than in this immaculate condition. Instead of showcasing visual reality, color emphasizes a statement: Another man’s bullet pierced a bone through another man’s throat. The same argument is displayed in the second image. Here, color bolds the blood that pours from the man’s dislocated torso. Yet this blood is pure red. In reality, such blood would not beam from a corpse; it would be dirtied and dried. Color again simplifies reality, highlighting to readers what happens during war.

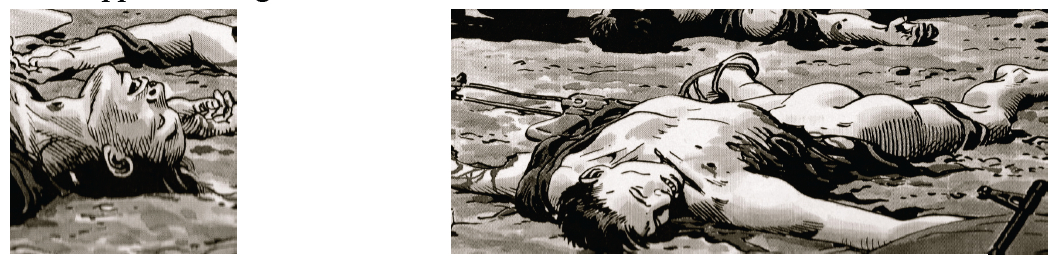

When the same images are displayed in black and white, such an effect is lost. Though readers may understand that the two men are dead, they do not see death’s marks etched in the corpses. The bone is barely visible, and the blood blends with the shading. The colored images are blatant to readers, who inherently understand what each detail represents. Such a technique attests to McCloud’s claim about drawing style: “By stripping down an image to its essential ‘meaning,’ an artist can amplify that meaning in a way that realistic art can’t” (30). Heath’s color truly “strips down” the panel to its bare essentials.

By simplifying a panel to its bare essentials, Heath presents color as an icon. As McCloud defines the term, an icon is an image that represents a person, place, thing, or idea (27). Cartoonists rely on icons to transmit a clear and obvious message to readers. In the case of this panel, the clearest example of an icon is the color red, which represents blood. Readers immediately connect the image of blood with its more powerful meaning: carnage. Heath chooses to depict such carnage through the visual device of an icon, and such an icon is displayed through color.

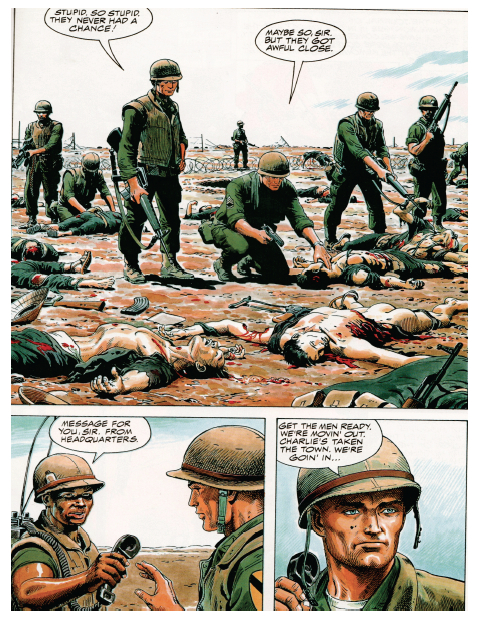

Beyond functioning as an icon, color breaks the flow of sequential art, emphasizing the subject matter of an image rather than the panel transitions on the page. Referring to the purposeful placement of juxtaposed panels, sequential art stresses the movement from one panel to the next, which, in turn, unconsciously forwards the plot. Looked at as an abridged filmstrip, sequential art carries readers from one important scene to the next. Yet, color seemingly cuts this artificial current.

The selected image comes from a page with three separate panels. Despite the wholeness of the story, color slows the sequential flow of these transitions. The first panel encompasses over a half of the page, warranting some sort of inherent importance in its size. Obviously, the artist wants readers to not only look at this image, but to study it in detail. Despite its size, readers may easily browse from one panel to the next. However, Heath installs color to prevent such an easy transition. After reading this page in its entirety, readers are inclined to revisit the first panel due to its colorful graphic content. The secret to such a phenomenon lies in the highlighter-like quality of color.

For example, moving left to right in the first panel, the focus shifts from the line of soldiers to the sprawl of bloodied corpses. Bold outlines of blood and flesh segment each corpse from the next, hinting that each image has a different story to tell. In fact, each body could be a separate panel. In the panel, four separate Vietnamese bodies are macabrely drawn: An American soldier tests the pulse of a clearly lifeless Vietnamese shell; another American soldier picks at a mangled corpse with his gun; and the final two corpses, torn and shattered, lay brutally close to the reader at the front of the panel. Subject-to-subject transitions would individually highlight each corpse and its features; yet, Heath decides to include multiple scenes in one panel, separating them by color. By choosing this method, color simplifies four possible panels (one panel for each corpse) and gift-wraps them for the reader. Realistically, each corpse deserves its own panel in order to communicate its graphic content, but color simplifies such reality into a single cartoonish image.

By segmenting sequential art, color also simplifies the significance of McCloud’s illustrious gutter. McCloud defines the gutter as the space between panels where closure occurs in reader’s minds. Through closure, McCloud suggests that the message of the comic is conveyed to readers. Such a claim raises the possibility that closure could be misconstrued: Reader’s could interpret a different idea than the artist intended from the panels. Color counteracts such discrepancy. Creating its own sense of closure, color illustrates the artist’s message clearly to the reader. Revisiting the panel sequence, I have manipulated the colors to a black and white format.

Reading the page, readers find that it is naturally much easier to follow the storyline in black and white. The first panel describes the recent conflict, and the gutter to the bottom left panel suggests to readers that such a massacre is a daily display for soldiers, as the sergeant plans to move out to another town. But, in color, such a transition is not so smooth. Color isolates the first panel, giving the gutter transition between the first and second panel a much different meaning. Studying the images in color, readers realize that the comic is exposing the absurdity of death through battles in war. The gutter seemingly empowers this statement, as it quickly introduces another future conflict that promises to be just as gruesome. Murray and Heath seem to be showing readers the horrifying realities of war. Graphic imagery, highlighted by color, communicates a “War as Hell” message to readers, who must digest an unnerving panel. Such closure can only be deduced when the panels appear in color. Without the red blood and displaced flesh, which are both only noticeable through color, the comic’s philanthropic message is lost in translation. Clarifying these important details, color simplifies Murray and Heath’s message. Rather than using words to communicate a difficult idea to readers, Murray and Heath rely on the simple but powerful effects of color.

Rather than making comics more realistic, color is highlighting the simple message of the images. Comic artists utilize color to highlight their ideas rather than bring them closer to reality. Magnifying minute details, colors strip down panels to their bare essentials, successfully forwarding the message of the artist. Manipulating the flow of sequential art, color simplifies complex depictions into a single panel. And, transforming the gutter, color clarifies a complex idea through universally understood graphics rather than confusing words. As viewed in a single page of Murray and Heath’s “Hearts and Minds,” a war related comic promises to introduce many ideas to readers. With so many themes floating throughout the comic, some sort of technique should aim to clarify and polish the author’s intended message. With that said, color in comics aims to simplify ideas so that readers better understand the artist’s message. Highlighting death and the absolute brutalities of war, color serves as a trail-marker for the artist, who only hopes to easily communicate some sort of message.

When an artist prepares to finalize his product, he must ask himself the color question: Could color simplify life more so than the comic already does? Heath’s artwork answers such a question. Indeed, even with color, simplification proves to be the root goal of comics. Color thereby is not so much an aesthetic choice to the artist as much as a literary tool.

When I met Heath a few years ago I expressed to him that I considered this book to be one of the best things he has ever done. He told me that he had never heard anything from anyone else about it.

If color is a literary tool, then in this case it is largely grammatically correct but stylistically problematic – the garish color scheme conveying the emotional range of a superhero comic. The limitations of the production process probably have a lot to do with this effect. The drawings by Heath are predictably polished, but are so concerned with anatomical beauty and precision that the severed corpse looks like an exercise in making the logically repugnant acceptable to the human eye (just look at that pristine chiseled butt).

I think this piece (quite apart from dissecting the grammar of color) also shows how looking at the single page can be misleading. I presume Melcher gets the “war as hell” message from the rest of the comic because all I see in this page is the honor and square-jawed courage required to annihilate a cunning enemy. The “actors” seem like Hollywood types, their speech patterns like something from a John Wayne movie. Why do these soldiers seem so different from those we find in Neil Shea’s article on Afghanistan: The Growing Menance (http://theamericanscholar.org/a-gathering-menace/) who have “come to do fucked up things” and who shoot dogs for pleasure (“What dead dog? He’s just taking a nap.”) Why is war such a noble process of devastating one’s enemies? Not every war comic has a duty to convey the anti-war message in question but there’s very little of that sentiment on the page being analyzed.

For the first 35 years or so as a comics artist, I rarely did anything in color. And when I say rarely, I mean RARELY — somewhere in the vicinity of 15-20 pieces total.

I honestly felt during that time span (and still do to some degree) that while color was nice, spotted blacks, cross-hatching, and other forms of shading could convey just as much, or more, power as color. In fact, I felt that color actually had a negative effect on the impact of some artwork because it distracted from, or watered down, the power of certain pieces or styles of art. For example, I much prefer Will Eisner’s original work on “The Spirit” in black-and-white.

In the past 10 years, however, I’ve become a bit more open-minded towards color, and have begun fooling around with it quite a bit more.

Like any artistic tool, it has a place, but even though I’m more open to color these days, I hate the way it is currently being overused in conventional pamphlet-style comics. I think such overuse muddles the power of art today, actually making stories harder to follow and enjoy.

Another example of black-and-white work I think would be completely spoiled by color is Steve Ditko’s amazing wash artwork for “Creepy” and “Eerie” during the 1960s.

Some people might feel this space scene I drew in 1982 would be enhanced by color: http://home.comcast.net/~russ.maheras/Planet-explorers-carnivor-TBG-cover-72-b-dpi.jpg

Maybe, but if you look at the way this page was composed, you’ll see that one’s eyes are drawn amost directly to the only spotted black on the page — which is clearly blood on the water — and then to the monster. After that, the eye begins to take in the surrounding vista and other palyers in the piece.

However, if this drawing were done in color, it would be harder to pull off the same effect using full color. One could probably pull it off if the cover was printed entirely in red ink, or if there was an overall pink atmospheric “fog” with dark red blood, but now we’re talking about changing “happy-to-glad” rather than the advantages of color over black-and-white

Very smart reasoning. I had never thought of color as a distancing, alienating effect…but come to think of it, so many productions of Brecht plays deploy extravagantly aggressive color– this post might explain why!

Grr, I hate the fact that today’s young’uns are about 10 times smarter than I…

Interesting that nobody seems to have commented on what seems to me to be the most controversial claim: “Color thereby is not so much an aesthetic choice to the artist as much as a literary tool.”

I think that fits with McCloud (who is a story-first kind of critic, right?) but it seems dubious to me, at least as a universal claim. Surely there are comics artists who use color first as an aesthetic choice rather than a literary tool. Fort Thunder and abstract work seems like it’s the obvious example….

I’m not, personally, sure what that claim amounts to: is it the claim that colour is always chosen for its representational content or ability to convey story-important features (mood, plot details etc.) rather than its purely visual aesthetic properties (e.g. “I just like the way that shade looks here”) or just its role in directing the reader’s gaze (“okay, stop and linger here”)? If that’s the claim, then it does seem as false in comics as in film, so I feel I must not be getting it.

I just assumed that he was referring to Heath and this story only. I don’t think anyone would make that claim for comics as a whole.

——————————

Phillip Troutman says:

The students are excited about sharing their work and, I trust, will be watching the comments closely. Please welcome them to the conversation.

——————————

Well, darn! ‘Way to make me feel guilty about finding fault.

Re “The Color Question,” there is a nicely-reasoned tone and command of the language here. Alas, although the writing shows intelligence and sensitivity, the premise comes across akin to finding complexity and philosophical profundity in people putting frames around paintings to display them.

What we have here is an able if unexceptional coloring job, aiding Russ Heath’s skilled drawings. There are no expressionistic effects in coloring and rendering; this is about as “realistic” as art can get in traditionally-rendered comics.

—————————–

Ryan Melcher says:

The first panel encompasses over a half of the page, warranting some sort of inherent importance in its size. Obviously, the artist wants readers to not only look at this image, but to study it in detail. Despite its size, readers may easily browse from one panel to the next. However, Heath installs color to prevent such an easy transition.

———————————

Even in b&w, there is also far, far more complexity to the first panel. While the following two are just “head and shoulders shot” and “head shot,” where the backgrounds are simple, unobtrusive. Therefore color’s effect in slowing down the pace of reading is minor.

Not that it’s nonexistent; studies have shown that a b&w scene is more quickly apprehended than a color one. (On a somewhat related vein: http://m.wisegeek.com/what-is-the-stroop-effect.htm .)

———————————–

Heath decides to include multiple scenes in [that first] panel, separating them by color. By choosing this method, color simplifies four possible panels (one panel for each corpse) and gift-wraps them for the reader. Realistically, each corpse deserves its own panel in order to communicate its graphic content, but color simplifies such reality into a single cartoonish image.

————————————

In what way is each corpse “separated by color” into “multiple scenes”? It’s not as if the lighting, hues or tonalities vary significantly from one to the other.

Even when there is great coloristic differentiation, do these marbles ( http://spaghettiboxkids.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/marble-games-for-kids.jpg ) come across as multiple scenes or panels, or simply as separate objects within one scene?

————————————

Indeed, even with color, simplification proves to be the root goal of comics.

————————————

Of course the color — as well as the drawing — are “simplified.” There is no grand literary strategy, aesthetic stratagem here. Much less it being a goal that is worked to achieve; ere rather than moving to Photoshopped-to-death stuff with every square millimeter of surface packed with gradients, comics would be ever striving for Alex Toth-like lapidary purity.

And comics would have progressed from this approach — https://hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/katana4.jpg — to this one: https://hoodedutilitarian.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/katana1.jpg .

Less-detailed rendering, with outlines around figures, colors and textures far less complex that what one would encounter in reality, are simply necessary limitations in an art form where papers were pulpy and less able to capture fine detail for most of its history, printing processes hardly high-end, artists, deadlines and budgets not allowing for Ivan Albright-like attention to detail and subtleties.

( http://www.fashion-res.com/EX/10-09-06/506679556_7b9c9b98cc_o.jpg – Detail from “That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door).” Even that canvas, which took Albright ten years to paint, is itself a “simplified” version of reality.)

And that a diminution of detail in drawing or coloring makes a work easier to “read” is a given, in the same fashion that a Dick and Jane book is less literarily-challenging than one by Henry James.

Here are a couple of works by my favorite painter where by composition and light, complex scenes are still broken up. If not as more distinct “panels,” Rembrandt’s strikingly theatrical lighting spotlights some figures, silhouettes others:

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Rembrandt_-_The_Blinding_of_Samson_-_WGA19097.jpg/1024px-Rembrandt_-_The_Blinding_of_Samson_-_WGA19097.jpg

http://panggilanhidup.net/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/nightwatch.jpg

Why, the latter is almost a collage of separate paintings! The old duffer fussily examining his weapon’s mechanism, the chaps in a tête-à-tête beneath the pike, the enigmatically flustered, spotlit girl; they might as well be inhabiting different worlds, are “separated” in mood from the whole.

While in Delacroix’s “The Death of Sardanapalus…

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/2/2f/Delacroix_-_La_Mort_de_Sardanapale_%281827%29.jpg?uselang=es

…somehow all the figures and “pieces of action” coalesce into an emotionally-unified whole.

Color can and should inform the narrative but it is certainly also comprised of aesthetic choices. Usually on the part of the artist….well, in American comics, NOT usually. Color is most often the poorly-paid ass-end of the process, handled by someone other than who was drawing the work. People like Steranko and Neal Adams had to fight for the right to color their own work for peanuts. Often the colorist seemingly doesn’t even read the pages being colored. I like to point to Kirby’s first issue of the Losers, which has a scene at the beginning that takes place at night. This is clearly denoted by the captions. Even the recent reprint repeats the original’s mistake of coloring the whole thing as if it is taking place in midday, destroying and wasting all possibility of drama. No one in the process bothered to notice or care, and that is typical. I doubt that many colorists read the scripts to see if the writers requested anything specific…that is, if the writers even bothered. Perhaps the artist asked for some specific coloring….Toth used to all the time, for instance, but either he was ignored or his notes were cropped from the copies given to those preparing the color guides, so it is likely that they never even saw them. Russ Heath is an extremely conscientious artist and a great colorist and so I imagine that what the author is noting was his decision. Heath spent a lot of his career drawing the bloodless, romanticized Kubert-style DC War comics; here he shows the actual consequences of war and it is an important gesture that HE made.

“I presume Melcher gets the “war as hell” message from the rest of the comic because all I see in this page is the honor and square-jawed courage required to annihilate a cunning enemy.”

I haven’t read the rest of the comic, so I don’t know the context of this page, but this doesn’t look like the end of an honorable battle where We beat Them. The Vietnamese corpses are all half-clothed or naked whereas the Americans are all unscathed. It looks like the end of a brutal battle where not even death brings the warriors dignity. War wasn’t hell for the Americans, but it sure looks like it was for the Vietnamese, one even ripped in half by the explosion.

By the way Mike, thanks for that Stroop Effect link. I’ve seen that test, but didn’t know it was called the Stroop Effect. It’s interesting stuff.

—————————

James says:

Color can and should inform the narrative but it is certainly also comprised of aesthetic choices…

—————————

Hope you didn’t think I was arguing otherwise! Simply was expressing dubiousness about the suggestion that the coloring Heath employed visually “separated” the first panel into scenes.

If color were to be used to divide a single scene into “reading” as separate panels, here’s some quick n’ dirty Photoshopping to show how it could be done:

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/Heath_War_color.jpg

Or with lighting:

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/Heath_War_lighting.jpg

Re unusual comics coloring approaches, “Roach Killer,” by Jacques Tardi and Benjamin Legrand, comes to mind:

————————–

What’s black and white and red all over? This book. The only color used is on the Blitz uniform and truck and on such archetypical red things as blood, Nazi uniforms, and stripes on the American flag. Indeed, Luis occasionally refers to Howard as “Santa Claus,” as Luis took off his uniform early in the story but Howard continues to wear his. This is a very striking visual convention, making Howard stand out like crazy (hah) in the gritty, black-and-white world of New York City. The final sequence, when Howard leaves the psychiatric ward, has his drawn image meandering through real B&W photographs of the city; what’s scary is that he still fits in….

————————–

http://www.rationalmagic.com/Comics/Roach.html

Or Frank Miller’s “That Yellow Bastard,” where the only color is that of the villain and his body fuids: http://noirwhale.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/noir-comics-sin-city-that-yellow-bastard-via-mk-goldenmoon.jpg , http://www.barik.net/journalimg/2005-04-04/Sin_City-That_Yellow_Bastard_6_p38.jpg

————————–

AJA says:

…By the way Mike, thanks for that Stroop Effect link. I’ve seen that test, but didn’t know it was called the Stroop Effect. It’s interesting stuff.

—————————-

You’re welcome! Makes me ponder the special “challenges” folks with synesthesia ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Synesthesia ) go through: “A green traffic light means ‘Go,’ but the word ‘Go’ is orange — and slightly furry — to me…”

(Famous “synesthetes” are Vladimir Nabokov, Robert and Sophie Crumb, Nikola Tesla…)

James: “Color can and should inform the narrative but it is certainly also comprised of aesthetic choices.”

I may understand the word differently, but where are the differences between color that “inform the narrative” and “aesthetic choices”? Do you understand an aesthetic choice as a decorative one? I would call that a beautifying choice, not an aesthetic one. Aesthetics have to do with how to convey some feeling or idea. If we’re talking about narrative comics, that has to affect the narrative being told. In this way color may be as important as the words. The fact is that it almost never is though.

No, that’s a literary definition of aesthetics.

Sorry, but consider me out of this discussion. Thanks!…

Color can be a crude narrative tool while aesthetics remain subordinate. An example would be the night scene mentioned by James. If it had been colored as a night scene in the most mundane way to fit the narrative then aesthetics wouldn’t play much of a role. For example the whole scene could be colored a flat blue. That would work for the narrative.

I’m so glad that these comments have touched upon the mentioned topics because these arguments are exactly what came to mind when I was writing this paper.

Before I begin to address some of these issues, I would like to thank Professor Troutman and Mr. Berlatsky again for this opportunity: It’s truly been a pleasure reading some of these insightful links and ideas that have been introduced.

I think it is important to note that I sadly am not familiar with Heath’s other works. I began this project wanting to write about war-related comics in general rather than a single panel. When I turned to this page in “Hearts and Minds,” I just couldn’t continue reading. To me, this panel had a story to tell aside from the rest of the comic, and in all honesty, the panel proves inconsequential to the central love story. With that said, I asked myself why this selected panel held my interest, and I concluded that the reason had to be color. This brings me to Ng Suat Tong’s argument: that Heath’s image isn’t necessarily dehumanizing war. After reading Neil Shea’s article, I can clearly understand your point. However, an avid Catch-22 and The Things They Carried faithful, I see the image differently. With color, Heath visually personifies the horrors of war that authors like Heller and O’Brien describe in their novels. Though it understandably could be construed as a “square-jawed courage” glorification, Heath reserves bright contrasts of color to illustrate the dead rather than the living. The line of soldiers remains a constant green, whereas the bodies feature different shades of color. However, this part of my reasoning (the war as Hell part) is truly my weakest, and offers another topic for discussion.

Again, I love reading about all of the related topics. These comments in themselves add a lot of “color” to the debate.

Hey Ryan. Thanks so much for sharing your piece. Glad the comments were helpful/interesting!

And please call me Noah.

Thanks, all, esp. Noah for inviting these papers and giving these students a chance to share their ideas with a live audience. While I was a bit worried about how Ryan would take the criticism, I think he has actually enjoyed it!

Look for more student papers coming soon….

———————–

Phil Troutman says:

…While I was a bit worried about how Ryan would take the criticism, I think he has actually enjoyed it!

———————–

A wise and mature reaction. Whether he agrees with the comments or not, it can be a learning experience to view one’s arguments from different perspectives; come up with defenses…

———————–

Graduate and postgraduate students are often charged with the unpleasant task of defending their essays large and small against professors in intense oral examinations.

————————

http://suite101.com/article/how-to-prepare-for-an-oral-examination-defense-a192202

…or modify them to remove perceived flaws.

While “print” (or TV or radio) critics may expound whatever and get little, if any, feedback, online is a different thing altogether.

Which makes one wonder: would utter nonsense like the auteur theory have made such headway in the present day? As it was, proponents for years published lengthy arguments making it seem the greatest thing since sliced bread, with naysayers barely getting to be heard.

I found it interesting that you analyzed colors in comics. People are always talking about what the things are in the pictures, but rarely do I ever hear anything about colors. I am interested to know what the effect is on reader for both images that are in black and white or color? i also want to know how colors or shades can effect the meaning of the story in general.

I think this is a really interesting paper that brings forth an aspect of comics that I have never even thought about. The examples you provided really make it clear how much influence the colors in the images have on the overall story they tell.

Similar to the actual transition styles used comics you seemed to place an importance on color that I haven’t heard before. Unlike black and white films, comics almost rely on color to get full point across. Going further than the image-text relationship, I think colors are the next important thing for an artist. I would like to propose a question, what would an artist/writer need to do if their comic was in black and white, do you provide more text?

There are lots and lots (and lots and lots!) of black and white comics. Most manga (Japanese comics) are black and white. They actually have less text for the most part.

Ryan, the color symbolism and use of color to slow the readers pace that you write of seems very pertinent to this example, and probably applies to many other color comics. However, I think it is important to look at the essential effect of black and white when laid side by side: contrast. While you claim that color can evoke a mood, I definitely agree, but I think that the sharp contrast between black and white can also effectively depict certain moods, such as tension. The art term chiaroscuro, meaning light-dark, refers to clear contrasts in shades and can often be used to create quite an eerie effect, seen in the works of artists like El Greco, and even in comic books like Epileptic by David B.

It was really interesting for me to see what colors can actually do in comics. But I disagree with you that colors in comics do not act to make comics more realistic. I think they do make comics more realistic because by adding colors to comics, one is bringing more detail. Think about it, we don’t see the world just black and white, we see the world with colors. Same goes with comics, by adding colors, one is making comics similar to what humans see; more realistic. Also, I would suggest that you use the black and white example first and color image next to convey your point because I have a feeling that after seeing the color images first, I already know what is going on in black and white images. But other than that, good work!!

I had enjoied reading your pice of work,you have touch intresting claim and point that most comics book have it. color is an important issue that reflect the work of the comics’ art in deifferent way. but I belive that black and white comics has been considered as a style of the these typs of books since it start in the past where it was not easy for them to print a color booked. so in that case many people have recongnize comics in a black and white form. but that doesnt mean they refuse the color copied or dont like it.it was clear how does the motion and the idea reflected differently into the reader mind by adding a color to the images.I like that you start with a color image first because it show the different and your point more than if you started with black and white because I said people have get used of seeing comics in black and white format and they already accepting it that way.

I never really thought of the color in comics or graphic novels as such a tool. I never thought anything of the difference between colored images and black and white images. Now I realize the importance of the use of color. Seeing the difference between the war images in black and white and in color. The reader can really connect with the emotion and drama in the scene when color is present. There is far less drama in the black and white scenes.