Judith Butler is best known for stating that “all gender is performance.” However, as far as I know, she never actually said that. What she did say was that gender was “an imitation without an origin.” By this, she meant that there was no “true” or “natural” gender — and, perhaps even more importantly, no true or natural gendered acts. So wearing pink wasn’t “natural” for girls, any more than playing football was natural for boys. Rather, every gendered action or choice (like wearing pink) was an imitation picked up from other cultural sources or discourses. But these imitations had no origin — only referents which in turn had other referents.

So, for example, a little boy might wear a pink dress imitating a princess in a cartoon. But the princess in the cartoon was herself wearing a pink dress in imitation of other princesses, who were wearing it in imitation of other stories or combinations of stories. The boy’s supposedly deviant gender expression is artificial…but the natural gender expressions are artificial too. Gender has no origin, which means that you can’t use origins to police gender. Queer people are no more artificial than straight people. Indeed, to the extent that their gender expression highlights artificiality (as in drag), their gender expression is more true, since it acknowledges the lack of origin which straight gender expression attempts to elide.

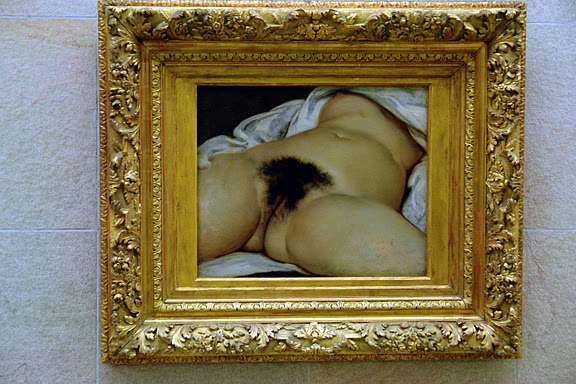

So in that context, let’s consider Courbet’s infamous, quite, quite NSFW painting, The Origin of the World.

This painting was a private commission, and eventually found its way into the collection of Lacan, believe it or not.

Obviously, Courbet in this image is linking gender and origins in a fairly flamboyant way. On the one hand, you could argue that, like the title says, the female genitalia are literally figured as the site creating, or birthing gender — the site of difference if you’re Lacan, perhaps. Gender is a physical reality, and woman is defined by that reality as a lack to be filled with looking. The person of the woman (like, for example, her face) is left off as irrelevant; all that matters is the gender, an origin without imitation.

But are we really supposed to take the title that literally? Or, to put it another way, isn’t part of the joke, and part of the satisfaction, that this is precisely a copy — a image of that which is not meant to be imitated? And the rush (or a rush anyway) is precisely the insouciance with which the imitation is an imitation. Contra Stanley Cavell, the point here is not the powerful illusion of reality created by what is excluded from the frame — rather, the point is the brass insistence that nothing outside the frame matters, that the copy, not despite but because of its artificially constricted view, is the gender and the world. Gender here is manipulable and diceable, packageable and consumable. The painting is fun and funny not because it shows you the profound, true origin of the world, but because it mocks that profundity — because it says that that profundity does not exist except as a toy for you to do with as you will.

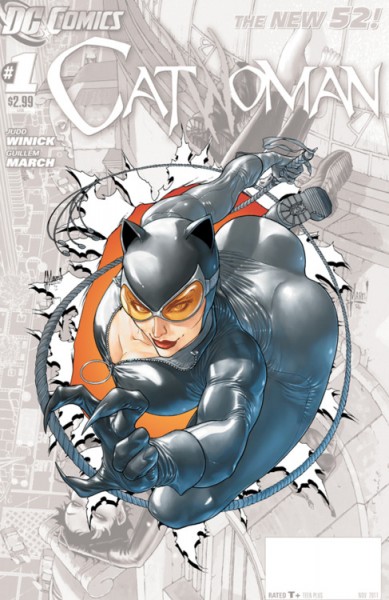

Along those lines:

In this issue, as you can see, Catwoman fights her posterior, which has attained sentience and is climbing up her spine to throttle her with her own sphincter.

Here, then, in Catwoman’s origin story, is a clearly ersatz imitation of gender — an imitation so ersatz that just by existing it makes the superheroine imitations its based on all look more than a little ridiculous. IF the truth of gender is artificiality, then this is surely as artificial and therefore as true, as gender comes.

But, of course, most critics of whatever gender and sexual orientation who have seen this haven’t enthused about its subversive liberation from the hierarchical hold of gender essentialism. Rather, folks have mostly pointed out that it’s incompetent sexist nonsense, which manages to look less like a real, actual human type person than Courbet’s severed torso.

For the Catwoman cover, then, a reference to origins — to real gendered bodies — is used as a check on an image that (semi-) deliberately indulges in artificial imitation. Here and (much) more competently in Courbet, the erasure of the origin leads not to a polymorphous free play of artificial gender possibilities outside of the restrictive hierarchy, but simply to a gendered imagining that hermetically, and gleefully, excludes actual women.

If everything’s imitation, if there is no real gender, then gender will simply be made and remade by whoever has the power — which is going to be the same people who always have the power. How do you say, “a cunt is not a woman,” if you’re not allowed to define “woman”? If there is no reality, on what basis can you criticize images for sexist distortions of it? Having to keep it real can certainly be oppressive…but, at least sometimes, it’s preferable to being someone else’s decapitated or spineless image.

______________

The title of this post is a crib from DCWKA. That Catwoman cover (which it seems cruel to attribute, but what the hey) was drawn by Guillem March.

I interpreted Courbet’s title to mean that the vagina is the origin of the world in the sense that everybody came from one… but your point is well taken.

Oh, yeah; I think that’s what he means as well.

Is there any evidence that Courbet was responsible for the title? It’s easy to ascertain titles when the pictures were displayed in the artist’s lifetime, or when contracts survive, etc. With such private, clandestine really, commissions it’s much more difficult, if not impossible. It could come from the patron, or some family tradition established later, or from the first critics to write about it… I’d research that question before making too much of the title.

“If everything’s imitation, if there is no real gender, then gender will simply be made and remade by whoever has the power — which is going to be the same people who always have the power.”

Butler gets around this with the ideas of appropriation and subversion, the idea being that over time the power gets redistributed. She’s also pretty wary of the idea that anyone simply “has” power, or “has” language… Power and language have you.

I don’t think that really gets to your question, though. Butler might say that the problem isn’t a failure to conform to real (it’s not a failure of representation), but a failure of citation. There are visual conventions for depicting women that are and are not sexist, but the judgment on whether they’re sexist has little to do with their fealty to “the real.” For example, is the cover above any less realistic than your average Kathy cartoon? Probably not. But it’s definitely more sexist in that it cites figure drawing conventions we associate with sexist texts and thus takes its place in a sexist tradition of citation that has consequences for women.

Andrei, you’re talking about the origin of the title, yes? I don’t think that undermines my discussion, though it might be a fun way to spin it out further.

Nate, that’s a clever end run…but I don’t know that it necessarily solves the problem. Yes, there are different traditions, and Cathy isn’t visually realistic. However, she certainly makes an appeal to realism in the content of the strip…and that appeal to realism is absolutely part of the strip’s purchase in and claims upon feminism.

I think it’s similarly tricky when you claim that no one has power, but that power has you. I recognize the post-structural elegance…but at the same time, there’s a point where the refusal to deploy identity in talking about power dynamics makes it quite hard to discuss those dynamics in a way that might be feminist. Terry Eagleton talks about this at various points; making people disappear into discourses undermines Marxism, not capitalism. Capitalism is perfectly happy with the infinite play of signs; Marxism, on the other hand — and feminism, and any politics that attempts to be liberatory — really needs some concept of people who are actual if those people’s actual suffering is going to matter.

So…saying it’s a failure of citation, and that some texts are sexist and some aren’t is fine…but if there aren’t actual women somewhere around, it’s hard to see what’s at stake in calling something sexism. It ends up being just tropes like any other trope, to be deployed or not as the spirit moves you.

Tania Modleski makes this argument more or less is Feminism Without Women — that is, she says that Butler makes women disappear, which makes feminism disappear too.

I’m with Aaron, though I assumed it was also a ‘chick or egg’ tongue in cheek mixed with the Oubouros of the womb, which Ripley and Giger want us to believe a) has teeth (that’s Victorian, does that make Giger steampunk?), and b) birth is the most horrific thing possible…except for giving head, as his latest work veers in and out of gay porn)

I don’t see a ‘severed torso’ but a woman’s body, which doesn’t show the head, or the complete legs – but as you don’t mention catwoman’s prosthetic leg, I assume you are able to envison the whole…but only if the torpedo nipple leads the way for the padded, but not wide ass – both so typical of some male artists that it seems no one sees the need for doing art from models (Nene Thomas, the fairie artist, does use female models, which is why her models don’t have a size FF breast going upwards and a G heading down).

The above seems to me that while gender is not finite nor absolute, it does seem to have an effect on the viewing and understanding of aesthetics, which seems a mixture of nature, culture/nuture. And if we are talking western, or Anglo western, pink is for boys, as any 1918 will tell, and blue for girls, as it follows the virgin mary, which is why a princess dress is not pink, it is blue. Simply watch the early disney Snow White if you are confused, she doesn’t wear blue because she is a boy, but blue becuase she is the ‘most beautiful (girl) in the land’ – just like Virgin Mary…which leads back to The Origin of the World. Of course, the other irony of that painting is that for women, it is just there, and who cares if the sheet is pulled away to cool it on a hot night, but for me, they throw away families, houses, jobs, and sanity all for it – now that not might be the most complimentary of viewpoints, but then neither are horny 15-25 year olds who hit on every female in view.

My phrasing was sloppy. Butler doesn’t say that power and language have us, but that because we are born into language (and the power relationships it inscribes) it’s all we have to work with. So language, like any tool, constrains even as it enables. And so we re-create, subvert, and otherwise perform gender. It’s not that gender isn’t real, it’s that it is a reality born from language. What’s real for Butler is discourse and bodies. Certain citations do violence (literal and metaphoric) to bodies. That’s why Butler locates discourse as a primary site of political struggle. Inthis respect by denaturalizing the notion of “actual woman” we can up the stakes of representation. Which brings me to the next point:

“(Gender) ends up being just tropes like any other trope, to be deployed or not as the spirit moves you.”

This is probably the rhetorician in me, but “just tropes?” There’s good reason to believe that metaphor structures our experience of the real (Lakoff & Johnson) and our politics (“death tax” anyone). Tropes have real power, and some more than others. So while you can deploy tropes thoughtlessly (which is what seems to have happened with that cover) you set of a chain of associations that can come back to bite you. So the use of tropes has definite consequences to bodies. This is especially true of tropes like synecdoche, which can reduce a person to a constituent part.

As for the infinite play of signs making people disappear, that assumes that something is only real or natural or true insofar as we didn’t make it (that it is unsullied by human hands). Just because gender is made in performance doesn’t make it any less real or true. It just means that what we take as true or real can be more or less stable over time. Sorry if this is all a little rambling. I’m finishing my second cup of coffee and getting ready to go to the library.

Hey Nate. You’re right of course that tropes are very powerful. But if tropes have power, and if words do, then I think you run into some problems with your point that gender can be true even if it’s performance. It’s not so easy to redefine truth, and not so easy to have a feminism if you’re not willing to say that women exist — which, again, is Modleski’s point.

“But if tropes have power, and if words do, then I think you run into some problems with your point that gender can be true even if it’s performance.”

I’m not sure why this would be the case unless you take it that if something is a product of language it cannot be true. As for words, gender, and truth,I’d argue by way of Butler (who is arguing by way of J.L. Austin) that language is performative and constitutes gender, which has bearing on the lived experience of real people. To the extent the performance is felicitous, i.e.,that it is accepted as true, gender roles are re-inscribed. You don’t need to deny that women exist, only that the existence of women as women is predicated more on linguisitic performance as opposed to biology (which is different from embodied experience, which Butler and Lakoff account for).

I have minimal knowledge of Modleski, but as I understand it her argument is that Butler’s account abstracts gender in a way that makes it difficult to speak of women as a group. This is true, so far as it goes, but I think it fails to account for the degree to which Butler acknowledges that gender is stabilized in language, and thus that there is a consensus discourse that makes woman a reasonably stable referent within a discourse community.

The problem is that it’s very hard to figure out a language community in which language is not seen as less real than biology, and similarly difficult to find one in which performance is not indicative of artificiality. Same with immitations and origins; you can insist till you’re blue in the face that the first is not less real than the second, but the language your using has a tradition and a social context, and those both push back against you pretty hard.

Butler’s very canny in her writing (and/or hard to parse because she’s not a very good writer, depending on your perspective) but at least as far as I can tell, the reason she wants to privilege imitation over origin is in fact because imitation connotes artificiality. She thinks that stable genders are oppressive, especially for queer people.It’s an anti-essentialist argument, not just an argument about where essences lie. Like a lot of the post-structuralists, she’s arguing against presence; there is no real gender, just provisional genders which are perhaps stable in particular language communities, but which drag and other subversive acts show up as artificial, thus freeing us all (provisionally).

My point is, abandoning essentialism and presence is notnecessarily fighting the power in the way that is sometimes suggested, not least because the power we’ve currently got is predicated on diffusion and imitation at least as much as it is on originary claims.

I agree with your reading of Butler and that abandoning essentialism and presence doesn’t necessarily mean fighting the power. I also agree (as would Butler) that language has tradition and context (hence the whole born into language thing). What I don’t agree with (and I don’t think you’re arguing this anyway, but correct me if I’m wrong) is that abandoning essentialism and presence amounts to an abdication of agency tout court. In fact, if power operates through citation then a return to presence could amount to a turn away from the problem.

It’s a good question whether abandoning presence means abandoning agency. Certainly, if you’re arguing with Foucault that discourses make people rather than the other way around, it’s difficult to see where there’s a space for human agency there, exactly.

I don’t exactly think that power operates through citation…rather, it seems like certain kinds of power are dependent upon certain kinds of epistemological visions. I think capitalism pretty explicitly depends upon an epistemology of non-presence — the invisible hand being the most obvious example (that hand being very much not God’s — the metaphor depends on the fact that the hand isn’t actually there.)

The agency question is a real bugaboo in rhetorical theory which was, until the post structuralist turn, started from the assumption of an actor acting on others via language (to put it in the crudest way possible). To work with the new body of theory required a rethinking of agency, where agency isn’t something one has or doesn’t have prior to a speech situation, but something enacted in speech. This po-mo rhetorical agency is of course less defined than Enlightenment agency, but it’s also more available. Of course, you could argue that this plays into the hands of late capitalism where we all get just enough agency not to freak out and topple the system.

I should note that much to the frustration of everyone around me I’m uncommitted on agency. I’ve been reading a lot of Latour recently, and he argues that agency is real but it’s less special and more distributed than we think. Basically, people and everything they make (and everything they encounter as they make things) have agency in the sense that they operate within a matrix of constraint and possibility. Not sure about it yet, but it’s interesting.

“Of course, you could argue that this plays into the hands of late capitalism where we all get just enough agency not to freak out and topple the system.”

I don’t think it’s quantity of agency so much as kinds of agency in capitalism, right? In capitalism agency is desire; you are the one who wants, and what you are is what you want. That has some obvious parallels with Butler’s pro-queer agenda, and is why the gay utopia isn’t not capitalism, in certain ways.

There are ways in which capitalism really isn’t the gay utopia, too…but I think to get there you need to be more willing to entertain the possibility of presence than Butler is. Love isn’t desire, but for that to be true you have to agree that love exists — and not just as an imitation.

I think we’re getting on the same page. I’m going to try to get my head around it:

“I don’t think it’s quantity of agency so much as kinds of agency in capitalism, right?”

I don’t think this is a yes or no question. Quantity affects kind and kind is often defined by quantity. After your get (or gain access to) a certain amount of agency the quality of agency changes dramatically. But I get what you’re saying. Capitalism privileges certain kinds of agency above others. Which gets me to…

“In capitalism agency is desire; you are the one who wants, and what you are is what you want.”

I’m having trouble with this. Desire is affective, not agentive. You can have desire without agency (you can desire agency). In capitalism agency=choice (or if you’re Marxist the illusion of choice). The going critique of late capitalism is that we have a lot of choices, and that gives us a sense of agency, but that the choices are largely trivial (brand of toothpaste, color of shirt), and so is the amount of agency we get. This confirms the following point:

“That has some obvious parallels with Butler’s pro-queer agenda, and is why the gay utopia isn’t not capitalism, in certain ways.”

I know many a grumpy Marxist who would say just this… That the politics of identity is a sop to the oppressed and provides an illusion of change. The base holds. I think this can be the case, but you could easily turn it around (as many have) and argue that Marxism fails to address the lived experience of individuals and in so doing subsumes distinctions between man and woman into an abstraction called the proletariat, the masses, etc. This is one the “ways in which capitalism really isn’t the gay utopia, too.”

Where I’m a little lost is on the love/desire thing. Why do I have to agree that love exists to say that love isn’t desire?

You’re a lot more rigorous than I am, is probably what it’s coming down to…but…

I take your point that desire is not agency…but I think that capitalism actually tends to elide that distinction. That is, identity and agency are constructed around desire; you desire therefore you are. That’s why specifically queerness, not just identity politics in general, parallels capitalism — because self is desire, and therefore desiring, or the ability to desire, becomes the essence of agency.

To desire agency in a capitalist context is actually something of an oxymoron, I think. Again, desire is agency; it’s the desire that makes you a subject, not what you desire.

I think that gets at what I’m trying to say with love. The object of love can’t be arbitrary if love is going to exist. Desire floats easily down the chain of signifiers, but I don’t think love can be that fluid. It requires essences if it’s not simply going to collapse back into another name for desire.

————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Butler…thinks that stable genders are oppressive, especially for queer people.

————————–

Hmph! So, one’s position in the gender “situation” is all flexible, a matter of choice?

Which can be seen as liberating; but for those who consider homosexuality utterly vile (’cause the Bible said so), it indicates gays are deliberately choosing to go against the Law of God.

And denying the existence of “stable genders” also buttresses the arguments of those who claim homosexuality can be “cured”…

—————————-

Nate says:

…Latour…argues that agency is real but it’s less special and more distributed than we think. Basically, people and everything they make (and everything they encounter as they make things) have agency in the sense that they operate within a matrix of constraint and possibility…

——————————-

I’m shocked to encounter such a common-sensical, “reality-based” argument!

Butler doesn’t really think it’s a matter of choice…but she doesn’t exactly think it’s a matter of biology either. And she certainly argues that heterosexual identities are every bit as much immitation as homosexual ones.

Still, there are tactical problems…and also problems in terms of excluding some people’s gender identities. Julia Serano is very eloquent in speaking about how Butler’s theories don’t fit her as a trans woman. That is, her identity as a woman doesn’t feel artificial at all to her …and people insisting it is artificial is one of the main ways that she (and other trans women) are discriminated against.

If desire makes you a subject how can you be an agent? Agency, in my understanding, implies a capacity to act. It seems to me that desire is a force that capitalism channels to its own ends- usually by making you want something. That’s the logic behind standing an attractive person next to a product, no?

I get what you’re saying about the love/desire thing. Love is definitely less fluid, which is why advertisers usually get to your love center by way of fear. “Buy this or you’ll lose something or someone you love.”

You’re a subject desiring, not a subject of desire. That is, agency is seen in terms of freedom to desire, and to act on those desires (through various kinds of consumption.) Agency is the ability to satisfy desire, and I think also the ability to desire itself.

Oh, I see. I misread. And you’re right, the freedom of choice is predicated on the freedom to desire, which is communism’s opposite number (communism usually defined as freedom from desire). That makes sense to me.

As for love, I think it’s as real as desire. Emotions are as physiological as they are psychological, and psychology is powerful thing. But I also think that once you start experiencing an emotion it gets tangled up with related signifiers and other, related emotions; whence the love that dare not speak its name.

Well, I’m an atheist, so it’s a hard sell for me seeing love as essence too…but I think it’s very difficult to arrive at a coherent critique of capitalism if you don’t.

You can probably sense my equivocation, also. After re-reading what I wrote, I realized I am presuming that love precedes language, which is something that is at odds with Butler.

My favorite critique of capitalism is maybe the simplest one, which is that for someone to win, someone else has to lose. I guess we could add, “So how would you feel if the loser was someone you loved?”

Yes! That’s a great insight that Butler doesn’t want love to precede language. And I think there’s plenty of reason to believe that love *does* actually precede language. Infants and animals can love, I’d argue