(Note: The following is adapted from a talk given at the University of Minnesota)

Here’s a fun trick, if you happen to be teaching a college level class: Squint out from behind that big desk or lectern or black treated-rubber-covered laboratory table on which you are banging your fists in a desperate attempt to keep your students paying attention to you instead of to Facebook and say unto them, Alright, raise your hands if you can remember the first time you ever used the internet.

Try it. Not right now, obviously, as I’d prefer you read this, and if it happens to be in the twilight hours going and getting a bunch of kids together might get you in trouble. Should you ever be amongst a large quantity of the yoots of America, try it. It’s an edifying experience.

And then, if you want to blow their minds, tell them that in ten years, none of the eighteen-to-twenty-year-olds you ask this question of will raise their hands. You’ll get lots of those mmms you hear from the audience during TED talks when someone has said something that feels profoundish.

I remember the first time I used the internet, of course. I had been logging onto BBSes—and even running one—for years. In fact, I considered myself (mistakenly) a fairly techno-savvy person. But I had never used the internet before the last week of August, 1997, when Joe Dickson showed me how to plug my computer in to Vassar’s Ethernet system, load up Netscape Navigator and go to visit a then obscure online bookseller called Amazon dot com.

Don’t worry. This isn’t going to be about nostalgia, even if nostalgia is one of the dominant modes of the internet. No. I’m far more interested in the ubiquity of the web and in the ways webbiness has begun to infect and affect the narratives we consume and create.

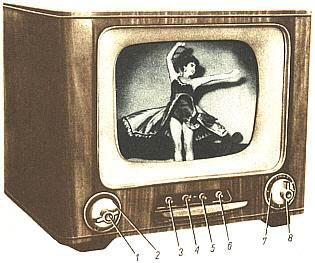

Twenty two years ago, David Foster Wallace was thinking about similar questions with his essay E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction. Noting that people spend more time consuming television than doing almost anything else, Wallace inquired into what happens to us when we spend the plurality of our hours as spectators as an audience staring, as he points out, at our furniture. What, he wonders, does it do to us when we stop interacting with the real world and spend most of our time not interacting with but rather absorbing fictionalized narratives about the world?

Twenty two years ago, David Foster Wallace was thinking about similar questions with his essay E Unibus Pluram: Television and U.S. Fiction. Noting that people spend more time consuming television than doing almost anything else, Wallace inquired into what happens to us when we spend the plurality of our hours as spectators as an audience staring, as he points out, at our furniture. What, he wonders, does it do to us when we stop interacting with the real world and spend most of our time not interacting with but rather absorbing fictionalized narratives about the world?

My guess is that a lot of HU readers have read the essay, and it’s way too long and complicated to summarize here. But to broad-stroke it for you, what Wallace ends up at is looking at the ways that “irony, poker-faced silence, and fear of ridicule are distinctive of those features of contemporary U.S. culture… that enjoy any significant relation to the television whose weird pretty hand has my generation by the throat.” Along the way he notes that “irony and ridicule are entertaining and effective, and at the same time they are agents of a great despair and stasis in U.S. culture,” while calling TV a “malevolent addiction,” because it holds itself out as the solution to a problem (loneliness) that it is abetting.

What Wallace is really after is the ways fiction could (and does) respond to all of this. To do this, he describes what he calls “Image-Fiction.” This term is a bit slippery. Wallace seeks to unite many aesthetically divergent writers (such as Don DeLillo, AM Homes, Mark Leyner and himself) under a banner that’s more defined by core values than actual noticeable artistic commonalities:

If the postmodern church fathers found pop images valid referents and symbols in fiction….the new Fiction of Images uses the transient received myths of popular culture as a world in which to imagine fictions about “real,” albeit pop-mediated, characters….The Fiction of Image is not just a use or mention of televisual culture but an actual response to it, an effort to impose some sort of accountability … It is a natural adaptation of the hoary techniques of literary Realism to a ‘90s world whose defining boundaries have been deformed by electric signal. For one of realistic fiction’s big jobs used to be… to help readers leap over the walls of self and locale and show us unseen or –dreamed-of people and cultures and ways to be. Realism made the strange familiar. Today, when we can eat Tex-Mex with chopsticks while listening to reggae and watching a Soviet-satellite newscast of the Berlin Wall’s fall… it’s not a surprise that some of today’s most ambitious Realist fiction is going about trying to make the familiar strange. (all italics in the original)

One of the problems with reading E Unibus Pluram today is that it’s a bit dated. This essay was written prior to both The Sopranos and widespread internet use, and so it’s tempting to say that everything has changed. Which, to some extent it has; the problems he’s discussing are true, but they’ve also radically shifted. Nevertheless, it provides a rather nice lens through which we can look at Jonathan Lethem—one of Wallace’s near-contemporaries—and how his latest novel Chronic City assays American humanity in the age of the internet[1].

Wallace is worried about what happens to a culture when it moves from being A Nation of “Do-ers and Be-ers” (his words) to a nation of spectators and consumers. We watch television, we buy things on QVC. Wash, rinse, repeat. This is not exactly true anymore.

Many readers of this post have likely heard someone on the radio or the teevee say something akin to “We used to make things. America doesn’t make anything anymore!” as a way of tracing our decline as a nation. Pretty much everyone who comments on the economy or politics, regardless of political ideology, ends up saying this at some point.

That statement—America Is Broken, We Don’t Make Things Anymore—is sort of true and sort of misleading. It’s not true in the sense that it’s actually meant. It turns out many many things are still manufactured in America. But—and this is an important but—not that many Americans are employed making them. Many of them are made, instead, by robots. So the statement “we used to make things” becomes true, even if the statement “we used to make things” is false.

It’s also worth thinking about the other word in that sentence: Things. We. Used. To. Make. Things. We don’t make things anymore. We have robots for that. So what do we make? We make cultural output and in particular, we make images. And many of us are doing this all the time. For free. On the internet. We are making animated .gifs and publishing them on tumblr. We are making memes of Ryan Gosling going “Hey Girl.” We’re writing long blog posts doing close readings of novels. We’re making short films and posting them to YouTube. And we love these images we create so much that we will go to a festival to see a hologram of a dead rapper perform.

This is having a profound effect on who we are, what the world is and how we perceive and navigate it. This is what, to me, Chronic City is about. As we’ll discuss in part two (now up!), It’s about these forces, ones that affect all of us, ones we don’t think about anymore because they’re the New Normal.

[1] NB: Chronic City is a large, long, thematically dense and at times deliciously contradictory and ambiguous novel. It’s also clearly meant to be read more than once. So please take this as A reading of the book rather than The One True reading of the book. If you haven’t read it before, I hope this provides you some sign posts for your own explorations within its streets and boulevards.

One thing I’m wondering after reading this is…is it a bad thing for people to be creating art (even bad art) online rather than…well, rather than what? What’s the alternative? Backbreaking labor in the fields? Assembly piece work? What’s the ideal thing we’re not doing now that we used to do, and why was it better?

Jean-Jacques Rousseau lives! And not only here. See also: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/17/opinion/sunday/first-theater-then-facebook.html?_r=1

——————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

One thing I’m wondering after reading this is…is it a bad thing for people to be creating art (even bad art) online rather than…well, rather than what? What’s the alternative? Backbreaking labor in the fields? Assembly piece work?…

——————————-

My mouth is literally hanging open here. How much money (that stuff people use to pay bills) do people make from…

——————————–

Isaac Butler says:

We make cultural output and in particular, we make images. And many of us are doing this all the time. For free. On the internet. We are making animated .gifs and publishing them on tumblr. We are making memes of Ryan Gosling going “Hey Girl.” We’re writing long blog posts doing close readings of novels. We’re making short films and posting them to YouTube.

———————————

At least the alternative which you dismiss as being “backbreaking labor in the fields,” “assembly piece work” (no other choices apparently available than those dismissive stereotypes), enabled one to earn that bill-paying stuff.

———————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

What’s the ideal thing we’re not doing now that we used to do, and why was it better?

——————————-

Moving from the rarefied to the nitty-gritty and down-to-earth: “We used to make things. America doesn’t make anything any more!,” while an exaggeration, notes that tens of millions of manufacturing jobs — which used to provide stable, well-paying employment, no college degree required, with plenty of benefits thanks to frequent unionization — have been destroyed due to automation or being moved overseas. (With the owners getting tax breaks and subsidies to do this!)

Just as a part of this phenomenon, this 2011 story reports:

———————————-

…the U.S.-China trade deficit has eliminated or displaced nearly 2.8 million jobs, of which 1.9 million or 70 percent were in manufacturing….

The impact of the trade deficit with China extends beyond U.S. jobs lost or displaced, according to the Alliance for American Manufacturing (AAM). Competition with China and countries like it has resulted in lower wages and less bargaining power for U.S. workers in manufacturing and for all workers with less than a four-year college degree…

————————————-

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michele-nashhoff/us-china-trade-deficit_b_984374.html

At least, as the stats tell us, the job market is increasing in the “service sector”…

————————————-

…how do we explain why almost 54 percent of recent college graduates are underemployed or unemployed, even in scientific and technical fields, according to a study conducted for the Associated Press by Northeastern University researchers?

The cause is more fundamental than the cycles of the economy: The country is turning out far more college graduates than jobs exist in the areas traditionally reserved for them: the managerial, technical and professional occupations.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics tells us that we now have 115,000 janitors, 83,000 bartenders, 323,000 restaurant servers, and 80,000 heavy-duty truck drivers with bachelor’s degrees — a number exceeding that of uniformed personnel in the U.S. Army.

———————————–

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2012-06-17/end-u-s-student-loans-don-t-make-them-cheaper.html?cmpid=hpbv

Hey Mike. The point kind of was that work for most people through most of history has been pretty miserable. That’s still the case for the most part, actually, I think, especially looking globally. Complaints about tv watching seem in large part to be complaints that leisure time has expanded to include a larger class demographic.

Noah,

I don’t think it’s a bad thing. But I do think it’s a complex thing, and that kind of major change in what we do is likely to have a change in who we are. So what I’m interested in is how our culture– how the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves– are dealing with this.

Wallace’s complaint is less about expanding leisure time and more about what happens when people can feel as if they’ve interacted with other human beings by watching them on the television and particularly what happens when writers get their material from scripted stories rather than actual social interaction. I think what CC is doing is updating some of those concerns for the internet/reality television age. I also don’t think the book is anti-internet or anti-leisure time or anti-television. I think it’s more anxious about what we’ve done with these things.

Is television really different from reading in that regard, though? Reading a book is interacting with a human being in the same way television is…that is, sort of and sort of not.

The Internet can be more like mail or a phone in that regard than watching tv or reading a novel….

I should explain my point above–that these kind of complaints about new media plunging the populace into passivity go back at least to Rousseau (to his “Letter to d’Alembert on the spectacles.”) And he addressed the notion of the novel as doing the same thing too–paradoxically, in the preface to his own novel, “Julie or the New Heloise” (of 1759). They are pretty easily deconstructible as nostalgia for an apparently less ‘mediated’ time (see the last chapter of “Of Grammatology”), and yet they reverberated well into the present, for example being restated by the situationists; Debord’s “Society of the Spectacle” is a fully Rousseauian text, which could have easily been used by Derrida in OG instead of, say, his use of Levi-Strauss. NNUTS. (Nothing new under the sun–i think I’m going to start using that acronym from now on.)

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

The point kind of was that work for most people through most of history has been pretty miserable. That’s still the case for the most part, actually, I think, especially looking globally.

—————————–

All too true!

—————————–

Complaints about tv watching seem in large part to be complaints that leisure time has expanded to include a larger class demographic.

——————————

Well, certainly there’s quite a contrast between “vegging out” in front of the tube and “making animated .gifs and publishing them on tumblr…making memes of Ryan Gosling going ‘Hey Girl.’ …writing long blog posts doing close readings of novels. …making short films and posting them to YouTube.” One of those rare cases of things getting better…

——————————-

isaac says:

…Wallace’s complaint is less about expanding leisure time and more about what happens when people can feel as if they’ve interacted with other human beings by watching them on the television.

——————————-

Heavens, about 20 years ago they did a test where a teacher walked in front of a class lecturing to them, while TV cameras photographed the teacher and broadcast him “live” to TV sets around the room. More students stared at the TV than the person in front of them.

And, an acquaintance reported seeing a young couple having dinner in a restaurant. Rather than talking to each other — they were facing each other a mere table’s width apart — they were texting each other. (Friggin’ idiots…)

———————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Is television really different from reading in that regard, though? Reading a book is interacting with a human being in the same way television is…that is, sort of and sort of not.

————————————-

Maybe philosophically, in that both are fictions. (Not that the image most folks present to the world is exactly what they’re *really* like.)

Yet studies of brain activity found that — unlike when reading — the brain goes into a passive state in front of the TV. (That’s why they call it “vegging out,” folks.) Moreover, the kind of show made no difference…

————————————

If you experience “mind fog” after watching television, you are not alone. Studies have shown that watching television induces low alpha waves in the human brain. Alpha waves are brainwaves between 8 to 12 HZ. and are commonly associated with relaxed meditative states as well as brain states associated with suggestibility.

While Alpha waves achieved through meditation are beneficial (they promote relaxation and insight), too much time spent in the low Alpha wave state caused by TV can cause unfocussed daydreaming and inability to concentrate. …

In an experiment in 1969, Herbert Krugman monitored a person through many trials and found that in less than one minute of television viewing, the person’s brainwaves switched from Beta waves– brainwaves associated with active, logical thought– to primarily Alpha waves. When the subject stopped watching television and began reading a magazine, the brainwaves reverted to Beta waves.

One thing this indicates is that most parts of the brain, parts responsible for logical thought, tune out during television viewing. The impact of television viewing on one person’s brain state is obviously not enough to conclude that the same consequences apply to everyone; however, research involving many others, completed in the years following Krugman’s experiment, has repeatedly shown that watching television produces brainwaves in the low Alpha range

Advertisers have known about this for a long time and they know how to take advantage of this passive, suggestible, brain state of the TV viewer. There is no need for an advertiser to use subliminal messages. The brain is already in a receptive state, ready to absorb suggestions, within just a few seconds of the television being turned on…

Better alternatives:

Reading (a book or magazine, for instance– not televised text. It is the radiant light from a television set that is believed to induce the slower brainwaves ) and writing both require higher brain wave states.

————————————-

Emphasis added; from http://voices.yahoo.com/your-brain-waves-change-watch-tv-low-alpha-349221.html

Even online “reading” fares poorly in comparison:

————————————

“Whatever the benefits of newer electronic media,” Dana Gioia, the chairman of the N.E.A., wrote in the report’s introduction, “they provide no measurable substitute for the intellectual and personal development initiated and sustained by frequent reading.”

…Critics of reading on the Internet say they see no evidence that increased Web activity improves reading achievement. “What we are losing in this country and presumably around the world is the sustained, focused, linear attention developed by reading,” said Mr. Gioia of the N.E.A. “I would believe people who tell me that the Internet develops reading if I did not see such a universal decline in reading ability and reading comprehension on virtually all tests.”

…Literacy specialists are just beginning to investigate how reading on the Internet affects reading skills….The only kind of reading that related to higher academic performance was frequent novel reading, which predicted better grades in English class and higher overall grade point averages.

…Some scientists worry that the fractured experience typical of the Internet could rob developing readers of crucial skills. “Reading a book, and taking the time to ruminate and make inferences and engage the imaginational processing, is more cognitively enriching, without doubt, than the short little bits that you might get if you’re into the 30-second digital mode,” said Ken Pugh, a cognitive neuroscientist at Yale who has studied brain scans of children reading…

Web readers are persistently weak at judging whether information is trustworthy. In one study, Donald J. Leu, who researches literacy and technology at the University of Connecticut, asked 48 students to look at a spoof Web site ( http://zapatopi.net/treeoctopus/ ) about a mythical species known as the “Pacific Northwest tree octopus.” Nearly 90 percent of them missed the joke and deemed the site a reliable source…

————————-

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/27/books/27reading.html?pagewanted=all

Hey, wait a minute! I had a pet Tree Octopus as a kid, and I won’t have anyone endangering this vital species through denialism.