Dreams seem like the most private of things, and yet in some ways they’re the parts of us that are least us. With consciousness sidelined, everything and everyone else takes their place in your head. Freud and Jung may not have been exactly right that you can unwind a person by unwinding their dreams, but I think they were correct to claim that dreams aren’t so much a window into the soul as a creepy acknowledgment that the soul you’d thought you’d kept in a safe place is always already in somebody else’s pocket.

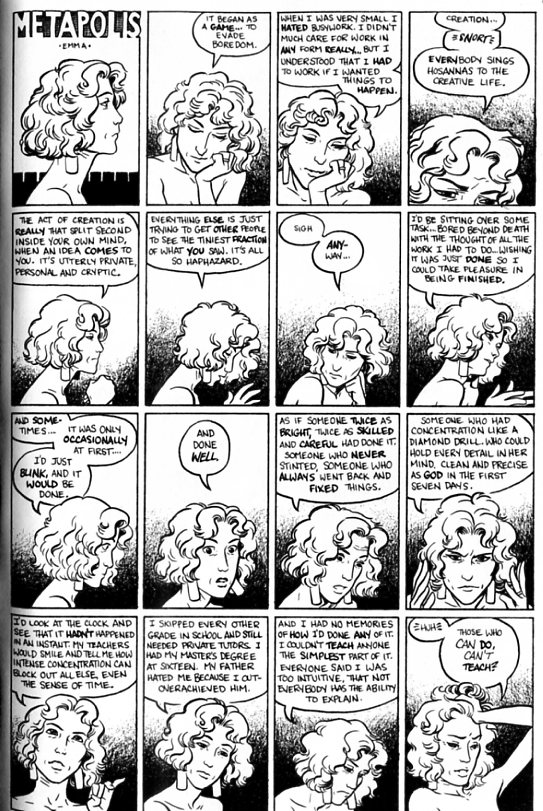

In “Sin-Eater”, Carla Speed McNeil’s first sci-fi Finder story, one of the main characters is a woman named Emma. Emma regularly has elaborate, disassociative dreams in which she imagines herself a fabulous princess in a distant realm. Sometimes when she’s gone, she lies as if asleep; sometimes she continues on with her life raising her kids and making her gardening eco-art without thinking or feeling or remembering how she did it.

Emma’s fantasy world is, obviously, a metaphor or analog for McNeil’s world which, like Emma’s, is elaborate and fantastical — a cyberpunk fantasy bricolage filled with talking animals and prophecies and even a venereal fey plague that gives people fox heads. Emma, then, is McNeil; a builder constructing a solipsistic interior castle, worlds within worlds, with emotions flickering across the page like carefully limned expressions across a mirror, the edifice an exercise in joyfully/painfully misrecognizing the self in its all its iterated containers.

But at the same time as Emma spirals inward, she spirals outward as well. The woman with the fantasy-world inside her is not exactly an original idea. I thought immediately of Neil Gaiman’s A Game of YOu, which could well have been an inspiration for McNeil (the timing’s about right, and Gaiman pops up in the copious notes at least once.)

Slightly further afield, I was reminded of Anna Freud’s 1922 essay Beating Fantasies and Daydreams in which she analyzes the fantasies of “a girl of about fifteen.” The girl is, of course, Anna Freud herself, and she traces her own rich fantasy life to a daydream she had as a five or six year old involving an adult beating a boy. Following in her own father’s footsteps, she interpreted these dreams as fantasies about father love; the father was beating someone else, which meant, according to Freud, that “Father loves only me.”

The daydreams were highly sexual, and in a guilty effort to suppress them and simultaneously enjoy them, Freud elaborated long, intricate narratives and worlds. Here’s her discussion of her main hero (she refers to herself in the third person.)

One of these main figures is the noble youth whom the daydreamer has endowed with all possible good and attractive characteristics; the other one is the knight of the castle who is depicted as sinister and violent. The opposition between the two is further intensified by the addition of several incidents from their past family histories-so that the whole setting is one of apparently irreconcilable antagonism between one who is strong and mighty and another who is weak and in the power of the former….

All this takes place in vividly animated and dramatically moving scenes. In each the daydreamer experiences the full excitement of the threatened youth’s anxiety and fortitude. At the moment when the wrath and rage of the torturer are transformed into pity and benevolence-that is to say, at the climax of each scene-the excitement resolves itself into a feeling of happiness.

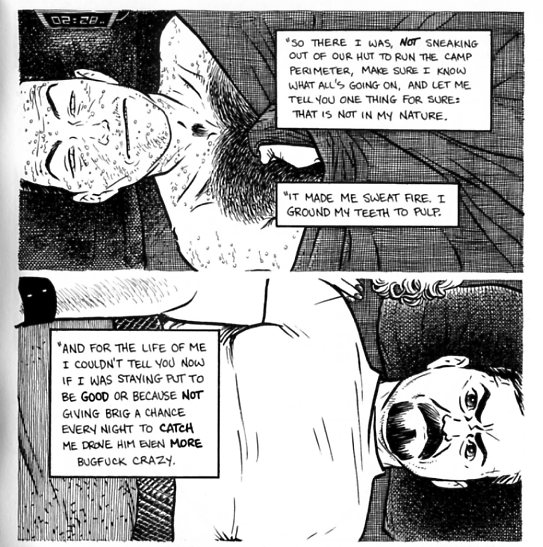

If you’ve read “Sin-Eater,” the connection between Anna Freud’s fantasies and McNeill’s fantasies should be apparent enough. Like Anna, McNeil’s story is obsessed with abuse — the main character, Jaeger, has a past which is basically one long series of fights, anchored by his decision to become a sin-eater, a sacrificial station that involves ritual beatings. As a sin-eater, Jaegar takes others’ wrath and rage and transforms it into pity and benevolence — a process aided by a mysterious healing ability which allows him to recover even from brain damage.

Moreover, “Sin-Eater,” like Anna Freud, has daddy issues up the wazoo. Emma’s former husband, Brig, psychologically abused her and her three children; Jaegar, who is Emma’s boyfriend, is a kind of substitute father figure — which is complicated by the fact that Brig served as a kind of substitute father figure for Jaegar himself. At one point, Jaegar actually builds a fake apartment for Brig to go to, fooling him into thinking his family is there rather than elsewhere. The displaced family obscures the fact that it’s not the wife and kids, but Brig and Jaegar who are constantly displaced, swapping one for another — as in this mirrored doubling.

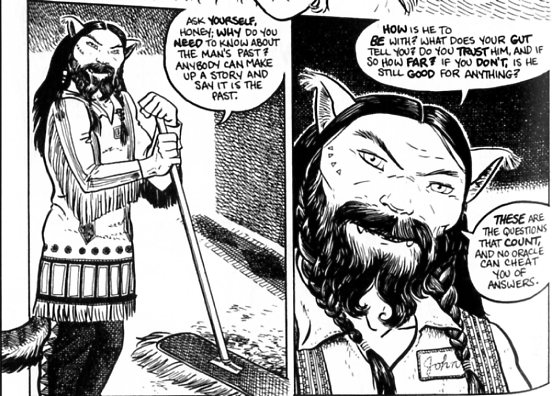

Or another example:

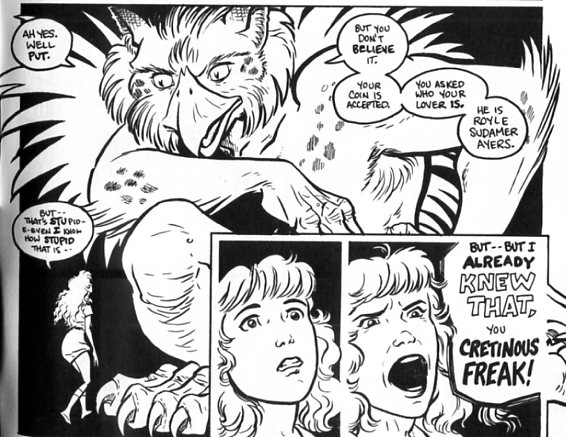

In the notes, McNeil says that this character is an early prototype of Jaegar. This early form is nonhuman, obviously — but it also has a beard not unlike Brig’s. And this dual Jaegar/Brig character is definitely an ambivalent father figure; it dispenses wisdom, but it is also connected to the oracle, which on the previous pages made Rachel (Emma’s oldest daughter) reveal her deepest fear. Rachel says her worst fear is “better the devil that you know” — an ambiguous statement that might be a little clearer if she’d said “better the daddy that you know.” Or, to put it another way, her greatest fear is the oracle, who towers over her as if she’s a small child and to which she reacts with a mixture of awe, fear, and petulance.

Again, this frightening oracle transforms into the proto-Jaegar, just as Jaegar takes Brig’s place in the family. The shuttling of father figures in and out puts a different twist on Anna Freud’s interpretation of her dreams. For her, the beating figure is the father, and those beaten are rivals for his affection. But if the father figure can shift from one place to another, why couldn’t he be the beaten as well as the beater? Couldn’t the point be vengeance upon the father by the (daughter identifying with) the father, a bid not for the father’s favor but for an economy which would grant power over the father to force him to identify with the (beaten) daughter? Father, then, becomes beaten and beater, and the happiness is from switching him from one to another, so that each punishes and then is punished for punishing, a cycle in which the powerful are humbled and the humbled empowered, so daughter is ever daddy and daddy is ever daughter.

Certainly in Sin-Eater the fathers take a massive and almost unending whupping. Brig is tricked, crippled, and finally rendered a howling, slobbering shell of himself; his son Lynn (who sometimes identifies as a girl, and sometimes as a boy), even injects him with battery acid. Jaegar, as we’ve mentioned, is constantly getting beaten up, falling from windows, mutilating himself, letting others mutilate him, and then healing and coming back. Ultimately he takes responsibility for the sins of Brig as well…spiritually changing the bad father to the good father, who apologizes and atones. (Plus there is the added bonus that Rachel can flirt with Jaegar unashamedly; he’s not her “real” father, after all.)

Which is to say, though the different clans and the background notes and the make it feel like a personal construction, “Sin-Eater” ends up as something very like idfic, pulling its power from the same well of chastened Daddy-lover fantasies as something like Twilight.

No wonder, then, that Jaegar is himself in many ways a drearily familiar archetype — the tortured tough-but-tender loner with heart-of, whose masculine ability to withstand pain functions as an excuse to subject him to hyperbolic and repetitive sensual violence, just as his mysterious outsider status turns him into a perpetually sexy invader of the quiet homes. Rachel accuses him at the end of the book of running out on the family because he fears that if he becomes less mysterious, they will reject him. But surely it’s McNeil herself who wants the outsider to be an outsider — she’s the one who made him in all his fascinating outsiderness after all. He’s a hyperbolic caricature of the bad boy who can’t commit; he gets physically ill when he’s cooped up too long, and then has to masochistically damage himself to regain equilibrium. Constantly disappointing and atoning, he’s forever attractively distant and adorably sorry for his distance; always that elusive first love, never the boring…well, daddy.

McNeill’s dreams, then, like Emma’s, are of genre — the most secret recesses of her heart are tropes. McNeill certainly knows that; she includes many wry allusions to other cultural touchstones (the Peanuts reference is a favorite especially.) Which would be fine…if I hadn’t run out of patience with the elusive, invulnerable Wolverine and all his sexily ambivalent loner brethren some time back. I don’t want to love him; I don’t want to enjoy his torment; I just want him to go away. But there he is, the angsty grain of sand at the center of the gloriously dreaming bivalve. Alas, I’m afraid that particular irritant’s been scraping my psyche too long already for me to really appreciate the pearl, however lovely its fashioning.

I think this somewhat supports the points you’re making here re: Jaeger… but one of my barriers to entry with “Finder” has been the extent to which Jaeger reminds me of Logan/Wolverine. Don’t get me wrong, I loved me some Wolverine back in the day, but the whole tough/feral/code-bound dude with occasional epic sideburns and a heart of a gold thing just… it just felt a bit old hat for a central character. I recognize this is almost entirely my problem and not Finder’s.

I don’t think it’s entirely your problem…or, at least, it’s my problem too. Having the lynchpin of the sprawling, careful fantasy world be an irritatingly familiar and derivative trope gives at least some legitimate cause for complaint, I think.

I’m not sure if it’s derived from Wolverine necessarily — they both could just be working off of Indian/longer archetypes. Natty Bumpo, etc. Though there is the healing factor….

Anyway, thanks for commenting! I thought lots of people would like to talk about Finder, which we’ve hardly ever discussed here (miriam talked about it a little.) But I guess it’s not as popular as I thought? Or maybe just not among HU readers, I dunno….

I’d think with the deluxe Dark Horse reissues that Finder would’ve gotten a lot more coverage in general! I have to say, I’m still stymied as to what all the fuss is about. The world that McNeill has created is genuinely fascinating and she has a lot of great ideas but, at least in the first omnibus from Dark Horse, she doesn’t appear to quite have the storytelling chops to back those up. There are numerous panels where the simple basic questions of storytelling (The who/what/where/why/how) are only answerable by flipping to the notes and reading a lengthy explanation of what’s going on. And the world building is so dense, and requires so much backstory info that I find myself feeling the same frustration I feel with Jaime Hernandez. Not to sound too transactional, but the amount of effort it takes to sort out why something matters in their work is not worth it. In both artists’s case, there’s a bewildering amount of information that seems largely to be in their heads and not on the page.

To put it another, totally mercenary way: Both Jaime Hernandez and Carla Speed McNeill’s work requires a certain level of digging just to get to the surface pleasure they act like they’re providing to the reader. They feel like they *should* work as pulpy entertainments with deep undercurrents of thematic concern, but they left out the “entertainment” part of the equation. For this reader, anyway. I know lots of people love both of them, but I’ve read plenty of celebrations of both artists, and plenty of in depth criticism (of the positive, analytical kind) of both and gone looking through their oeuvre’s to find what people are talking about to no avail.

Then again, world building is almost never my thing as a reader. I admire it, sure it can be impressive and in some cases a lot of fun, but it’s rarely what I come to stories for.

I can enjoy world building in some cases…I like LOTR a lot.

I think for both McNeil and Hernandez, the depth and the fact that information isn’t immediately available is supposed to be a feature, not a bug. The fact that there’s more than you know is supposed to make the world seem more real, and allow for a kind of obsessive investment. So the surface pleasures are the confusion, at least to some degree.

It’s not my thing either exactly…it’s interesting the way that both seem to be tied into or at least tangentially related to the comicbook minstream multiverse fan-model of investment in minutia, even though they go very different places with it than the mainstream.

(McNeil is definitely a Love and Rockets fan.)

Many’s the time I’ve thought “Since the first book is the one everyone wants to start with, and it’s a ride on the fire hose more than it is a story, hm, shouldn’t I redo it?” But that’s a tar pit. Thanks for the genteel poke with your walking stick; I’ve been reading HU off and on for a while now.

The first two books focus on Jaeger as a central character, and he turns into more of a common thread to unite stories later. It’s a extensive fictional world being described, so there is a certain utility to having a wandering, powerful character to unite the stories together. One could draw an analogy here to Usagi Yojimbo, I bet, if for no other reason than it’s a fun thing to do.

It would be interesting to build an analysis of him and the story structure in a Jungian rather than a mostly Freudian mode as you did here, but my brain isn’t up to that on a Saturday morning, and I’m sure I’ll have a better excuse by this afternoon.

Like a lot of long comics series (Love & Rockets, Cerebus, to name two favorites) the first volume is usually the least successful one. I’m a fan of Finder, but I actually started reading it somewhere in the middle and then went back to read the rest.

The world building is a big part of the book, perhaps moreso than the characters themselves. I do see the annotations as a feature not a bug, as I wrote awhile back in re v.8 of the series:

“Some might say that this is a failing of the story itself, but I’d argue that it is a strength. While, annotations to stories often feel superfluous or tacked on as an afterthought, McNeil’s notes draw out the story. It’s just another way of handling the image/word interaction of comics, another way the images and the text are integrated with each other, one requiring the other.” ( http://madinkbeard.com/archives/finder-v8/ )

I like the notes…and at least in the first book, I think Sin-Eater is the story I like most (King of the Cats and Talisman are both enjoyable, but not as ambitious, I think.)

But more importantly…Carla, I am now both flattered and sheepish. Thank you for your gracious response.

Although I consider your review to strike quite a few interesting chords, I find myself disagreeing with many of your conclusions.

First and foremost the psychoanalytic patterns in “Finder” are in my opinion to be much more Jungian, than Freudian in nature, especially because Jung’s theories proved to be much more influential in mainstream storytelling techniques than Freud’s. With your emphasis on the father theme in this graphic novel, you are rhetorically emphasizing one aspect of a complex psychological situation, only to lateron refute that and decry it as unoriginal.

Although McNeil’s work is very heterogeneous and in many places lacks narrative coherence (which is not surprising for a then debuting artist), she makes it very clear that Jager is not her main character, but rather a dominant figure, as the psychological development is definitely much more significant for the female characters.

In my interpretation of “Sin-Eater” the themes in these disparate developments are not – as you insist – limited to the resolution of “daddy issues”, but individualization within a fictional tightly structured society and familial setting. This converges with her usage of tropes/Jungian archetypes and is further emphasized by her use of distinct physical spaces and thematically matching architecture. The narrative contrast and suspense is derived from the psychological dissonance between their assigned roles/archetypes and their individual expression.

This goes as far as being directly mentioned in the Gaiman scene you referenced.

McNeil’s reliance on tropes is therefor not derivative, but the rhetorical prerequisite for a narrative style of a work inside the pop culture: The reliance on archetypical characters allows the individual psychological conflict and at the same time, the consumption of “Sin-Eater” by a pop culturally infused audience.

In short, Jager would be an uninteresting archetypical “wolverine” character if it wasn’t for the fact that he himself possesses enough self-awareness to question his own role and feel the constant need to justify his own behavior. And the same goes for all the other characters in “Sin-Eater”.

Maybe my arguments will not convince you. But then again… How many graphic novels do you know which actually allow such an in-depth debate about narrative patterns and the psychology of the characters at all?

I know this is a somewhat negative review, but my interest has been piqued. And I think my tolerance for Wolverine is higher than yours, so I might really enjoy this comic.

Yeah…I think I may have convinced my wife to try it too; she’s got more tolerance for angsty loners than I do, and she quite liked the art.

kaminkatze, as I’ve mentioned here recently, I think any work can generate lots of analysis; that’s sort of how texts work.

In any case…the point about Jung is interesting. I’m not all that familiar with his writing (except second hand through Joseph Campbell), but I think Anna Freud’s essay is sort of at an interesting juncture between her father and Jung. Or at least, I think you could read her essay in a Jungian mode without too much trouble.

Pointing out the pomo aspects of Finder is smart too…they’re even stronger in “King of the Cats”, perhaps, which is set in a Disney-world like theme park. The rejection of the modern and the idealization of the primitive there kind of puts me off…though she does complicate things (her “primitives” use technology, have a complicated culture, etc.)

I should add…I read the whole book, which is more than 500 pages, and that’s despite the fact that the book is not exactly a page turner. There’s a lot to like…so I’m not exactly negative — more ambivalent.

Oh, I’ll confess to the Wolverine thing, no point in denying it. Many times I’ve wished I hadn’t incorporated the quick-healing thing, and many times I’ve tried on and discarded various reasons for it. I’ve hit it with a whole lot of sticks to make it serve the story rather than just be an appendix to an earlier stage of my life as a reader. I’ve never been as adept as Jaime Hernandez in just walking away from things that don’t work… probably wouldn’t have been as bad to do so as I thought given how many other loose ends I never got back to from the early books.

Ha!

I should say, a big part of my reason for Wolverine-antipathy is that I (like everyone else) was really into the character for a long while there as a kid. Then I took a break…and then my own son (who’s eight) was really into him, and I realized, revisiting him, that I’m just thoroughly sick of everything about the character.

Maybe in another ten years I’ll swing back around….

I don’t blame you; if there ever was a blown-out sock puppet of a character, it’s Wolverine. I’m not sure any character that has been interpreted as a pasta shape in orange tomato sauce can ever really have new life reimagined into him. But then someone like Aaron Diaz gets his hands on him and (this being the important part) departs radically from most of what’s gone before, and I find myself biting my lip and wishing I could read THAT book. It gets tiring, trying to assess whether the latest barnacle-scraping is more or less successful than the last one, leaving aside the fact that there are other, often better, ways to structure a story than just letting the character run things. But the idea’s in my head, and pretty deep in, so I have to cultivate it.

Ms. McNeil’s Jager certainly has, as kaminkatze astutely noted, archetypal qualities, of which Wolverine is only another expression. (Is Wolverine’s healing power not like that of…nature?) One predecessor:

————————–

Enkidu was first created by Anu, the sky god, to rid Gilgamesh of his arrogance. In the story he is a wild man, a Tarzan figure, raised by animals and ignorant of human society until he is bedded by Shamhat. Thereafter a series of interactions with humans and human ways bring him closer to civilization, culminating in a wrestling match with Gilgamesh, king of Uruk. Enkidu embodies the wild or natural world, and though equal to Gilgamesh in strength and bearing, acts in some ways as an antithesis to the cultured, urban-bred warrior-king…

————————–

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Enkidu

Not only an archetype, but the “tough but sensitive wild man” is a stereotype, a term not necessarily negative. As stated in an old TCJ message board post:

—————–

ster·e·o·type

….

Sociology. a simplified and standardized conception or image invested with special meaning and held in common by members of a group:The cowboy and Indian are American stereotypes.

—————–

The great graphic designer Milton Glaser spoke favorably of the “power of the cliché” in illustration and advertising; how it can communicate immediately.

Thus, a cliché/stereotype – the hooker with a heart of gold; gruff, boozing, but incorruptible private eye; noble Native American in touch with Nature; wizened Oriental who is a fount of spiritual wisdom – may not have the distinctive qualities and complexity of an individual…

(Which, yes, makes for complaints from some quarters. But sometimes a character is stronger, more clearly delineated, as a “type.” Sauron would in some ways have been enrichened, made more complex, if we’d learnt he had a lousy childhood, had phobias about catsand dirt; but, also diminished. For instance, a highly symbolic comics character such as Captain America dwindles when facing humdrum, home-grown militias rather than Nazis or a Red Skull.)

… but from a narrative point of view is exceptionally useful.

Why did Hitchcock use famous stars in his leading roles? Because he knew they brought to an audience, aware of their images from past movies – Cary Grant as a Smooth Operator, James Stewart a beloved Everyman – the favorable qualities of a stereotype. Hitch didn’t need to spend valuable screen-time in getting the audience to learn of and appreciate these qualities in the characters.

In fairness to McNeil, not having read “Finder” (never made it to the shelves of the local comics shop I patronized), Jager might be fairly individualized. Still, possessing those archetypal/stereotypical qualities facilitates readers’ relating and appreciating the character; is certainly a valid creative strategy.

McNeil’s written an arc of Finder (“Dream Sequence”) that is mainly devoted to the kind of anxiety of influence issue you’re taking her to task for here. Part of your criticism seems to be that Jaeger’s not your type – allegedly on Freudian grounds, or that you’ve somehow gotten the archetype he belongs to out of your system as a child, which, okay, happens. The ****ability-or-not of the main character is always an extra draw, and that’s down to personal taste, but does that really make or break a comic for you?

(side note – it does – Dresden Codak (by who-I-now-realize is the aforementioned Aaron Diaz (McNeil’s cited him elsewhere)) is inventive and brilliantly constructed and though I hate the politics which are its main reason for being, the point is I read it maybe three times as often as I would if the protagonist weren’t the precise cute world-ender type I’ve never gotten over to my cost. Do people get over types? Nonsense, they don’t! We just learn to run, and comics are okay, they can’t chase you).

The critique McNeil’s choosing to respond to here (and in Dream Sequence) is that we’ve identified an influence in her work, which is a marketing disaster and also class treason – simply admitting you read comics puts you on a plane with the people you’re trying to flog them to, and admitting to a previously-used idea negates the impressive species divide that’s meant to drive the authorward flow of cash like tropic-polar heat differences used to drive the jet stream. All is lost, Carla, thanks to you!!!

Dream Sequence is a magnificent read – it discusses the artist as a marketer, as every artist is or he or she is never going to benefit anyone with her (in the comic, his) art so why make it? Getting someone else to do the marketing, is itself marketing, and part of the artist’s job. Cue Chesterton on the artistic temperament being a disease that doesn’t afflict artists. Letting the Wolverine reference show is a marketing error – and in that sense, an artistic one. But it’s a balance with enobling and empowering your readers instead of simply beating them down. An artist should get to where they’re tripping themselves up for the benefit of the reader, and showing how the magic is done. Dream Sequence ends with Jaeger (or a projection of him, as hallucinated by a character with daddy issues who’s _just realizing he’s gay_) urging a reader stand-in to start writing their own stories so as to escape the author and their lethal reverence for him.

There’s so much more going on in this book than Kimiko’s breasts – I mean her “refreshing lack of grace” – oh, wait, not Dresden Codak – we were discussing Finder! Ahem. There’s so much more going on than Jaeger’s psychosexual appeal, and McNeil’s admitted crime of letting her mere humanity show (wait – she had a childhood?) betraying the calling of Author.

(No offense, Noah, this unfair post is mostly to get back at that smug jerk who hectors Magri in Marcie’s cafe. Grrr.)

It’s funny…the Claremont X-Men were in retrospect pretty iffy in a lot of ways — but compared to the mainstream now that run looks like genius. I tried to read that Avengers/X-Men battle thing which I guess is very successful, and…yeah. Pasta shapes and barnacle scrapings seems almost too kind.

I just reread this and the altogether vicious tone is due to my idiocy in failing to do a re-edit. I’m very sorry, I’m showing venal smugness which I could have managed to conceal, and that _is_ an artistic failing.

It’s not vicious at all! It’s got a bit of an edge, but so does my review; nothing wrong with that.

I must be very dense in that I never picked up on the Jaeger/Wolverine connection.

I can’t be the first person (I mean, outside Carla) to make the Jaegar/Wolverine connection…but google isn’t instantly showing me other instances….

In other google failures…I’m not finding the Aaron Diaz Wolverine? Or I can find some references, but I don’t feel like I’m looking at the right thing? Anyone care to elaborate?

Why yes! http://dresdencodak.tumblr.com/post/24574027688/dresden-codaks-x-men-reboot

I expect plenty of other people have noticed the similarities and just didn’t rub my nose in it.

Heh. The world if full of people more gracious than I….

“The world is so full of a number of things, I’m sure we should all be as crazy as bedbugs.”

———————-

Des Pickard says:

…Getting someone else to do the marketing, is itself marketing, and part of the artist’s job. Cue Chesterton on the artistic temperament being a disease that doesn’t afflict artists.

———————-

Two Chesterton comments on the “artistic temperament”:

———————-

The artistic temperament is a disease which afflicts amateurs.

———————-

Artists of a large and wholesome vitality get rid of their art easily, as they breathe easily or perspire easily. But in artists of less force, the thing becomes a pressure, and produces a definite pain, which is called the artistic temperament.

———————–

(More splendid quotes by him at http://quote.robertgenn.com/auth_search.php?authid=247 )

————————

Carla Speed McNeil says:

http://dresdencodak.tumblr.com/post/24574027688/dresden-codaks-x-men-reboot

————————-

Wow, those are some outstanding character designs! (Thanks for the link.)

Alas, getting to the second set of characters, Warren Worthington III was drawn looking blatantly gay. Though it turns out he’s not (the more butch-looking Piotr Rasputen is), Warren is described as “…one of those kids you want to punch, and not just because he’s an out-of-touch millionaire…Visually I wanted something fashionable and punchable.”

So if a guy looks “poofy,” the natural reaction is to want to hit him? OK…

I interpreted that to mean that Aaron was creating a character with a glossy superficiality, that he would present himself with insufferable vigor, a mutant reality star, and any characteristic he adopted would grate. In terms of character creation, I’d say it’s more a “punish your bastards.”

Noah, thanks. Never much liked Wolverine myself, as a kid, since superheroes who killed were just wrong (now I’ve upgraded it to global superpowers and I’m a Noam Chomsky fan, lifelong prig, I know); But I don’t think straight women readers get just one shot in history (even in comics history) at the sexy, fully-breakable man who’ll just repair himself whatever you do to him so it’s okay.

Straight male readers get their more exciting female archetypes over and over and in many guises in comics – and we tend to judge authors on how they employ the archetype, in what stories and to what end. Speed has plenty of cheesecake to go along with the beef, and Jaeger is aware of how implausibly male he’s being and how the story’s other male characters aren’t. He’s a fantasy, but he’s also an ideal that Speed’s trying out, and her male and female characters – the urban ones – along with her. Jaeger’s trying to escape being Jaeger, as all the while, characters like Rachel and Magri are trying to figure out their way in. If some of us get titillation in with the package – that’s gravy. Jaeger’s somewhat about what you can get away with, like bad boy Wolverine, but he’s also an experiment about deciding to get away with nothing, and whether it’s ever possible.

Finder is obsessed with ideas of self-sufficiency and what they say back to corporate culture, media culture, and liberal urban culture in general. She’s walking a fine line with noble savage material – walking it capably, if I can judge although I’m a white middle-class New Yorker – at least, her noble savages are pissed as hell about the noble savage idea; but she’s picked a world of tight-packed city dwellers surrounded by nomad-haunted wilderness for a reason – I’m thinking Ayo’s dream from Dream Sequence, which from the notes is one of Speed’s apparently instilled by a Star Trek episode discussing overpopulation – just this terrifying vision of people packed in like boiler hens in her domed cities, and what that means, whether there’s any control at all, any responsibility for societies built around extreme injustices, and whether it isn’t all about to come crashing down – not a bad vision to contemplate at this historical moment.

More than that, how do you benefit from civilization without becoming a pure consumer of it – an addict – and giving nothing back? How do you make room to give something back? Her characters (in this and other works) speak about the circuit that never gets closed, that gets burned out if you take in art without responding in art, if you consume without meaningfully producing.

I dunno – I find Finder brilliant and frustrating. You get a profusion of picaresque sci-fi weirdness like in her current “Third World” story arc, which is lovely, but comes in a bit of a barrage; you get delicious assaults on mass-marketed political sentimentality as in “The Rescuers.” it’s difficult, dazzling work, and I hate having my favorite comics character compared to Wolve-freaking-rine because they’re hot in similar ways.

Noah, thank you for your gracious response and thanks also to an acquaintance who read this and reassured me I wasn’t being a boor but just sounded like a stoner. :^) Noah, I’d like to see a followup review of one of Speed’s more recent works. ‘Til then I’m glad to have found this quite articulate and thoughtful comics review blog.

I’m not sure it’s quite fair play to say “I didn’t care for this because it reminded me too much of something else”, unless the point of that is to say the work’s actually bad because too derivative? But if it doesn’t have the flaw of being derivative, then it seems to me the reader’s involuntary recollection of Wolverine probably isn’t germane. So, we’ve all got X-baggage, I guess, but can’t we put it aside every once in a while? Is X-baggage the only baggage that counts? I could say I liked this because it reminded me of Steve Englehart’s Coyote as easily as I could say I didn’t like it because it reminded me of Wolverine, but this is taking anxiety of influence and turning into panic-attack of influence, I think…even if I think the Coyote comparison is quite a bit more fruitful than the Wolverine one…because really I am liking Finder right now (I just got it the other day) because I think it’s very good on its own merits, and neither Wolverine’s nor Coyote’s recollection is at all central to my reading.

And I’m quite surprised to find out that’s just me, you know?

Hey plok. As a critic, I’m not especially interested in being fair. I’m interested in figuring out my own reaction, and I’m interested in figuring out how the work is put together, and I’m interested in connecting both those things to other works and ideas I care about — but none of that has anything to do with objectivity or playing by a particular set of rules.

In this case, anyway, the point wasn’t to say that Finder was bad because it was derivative. All work is derivative; art’s made out of other art.

Who mentioned objectivity? Not me!

That wasn’t exclusively pointed at you, Noah, since others have noted their “Wolverine thing” with it as well. But I am a bit surprised that you say as a critic you’re not all that interested in being fair? You must draw the line somewhere though, I imagine: like, you wouldn’t not like a book just because you saw a picture of Nixon reading it, or something?

I did notice that you didn’t say you thought Finder was bad because it was derivative, but rather that the memory of Wolverine interfered with your enjoyment of it. And that’s a little bit interesting, you know, if Wolverine has contaminated your appreciations to a certain degree? But like I say, I find the interest in Wolverine (even if it’s negative interest) as a precursor to Jaegar rather surprising. Don’t worry, I’m not going to say you need to unpack all your Wolverine baggage right in front of me in order for me to think this was a “good review” or anything! But like Derik, I didn’t even see this Wolverine stuff, and actually I do have Wolverine baggage of my own, so…

I wonder what the difference is? Why did it hit you and others so forcefully, and miss me completely? Well, hell, I didn’t even know Wolverine was supposed to be “sexy” in the first place…

So, it isn’t exactly the meat of your review, but I found it curious.

You did see that Carla said Wolverine was a direct inspiration for Jaegar, right? (Scroll back up through the comments if you missed it.)

I guess I don’t really know what “fair” necessarily means in this sort of context. I try to be honest about what I think, but sometimes that means not being especially balanced or measured. I don’t really know what the Nixon picture has to do with that…I doubt I’d downgrade something just because Nixon read it (though never say never…), but if it jibed with Nixon’s actions in some way, I wouldn’t hesitate to point to the picture and discuss the connections.

Oh yes, I saw that…and it’s interesting extra information, but my reading’s still one that involves Coyote a lot more than it involves Wolverine: those just happen to be my reactions. But, well, the context is very different from yr basic Wolverine story, right? So I don’t feel like I was missing anything by not seeing Wolverine there, and really I still don’t see Wolverine there, though it’s interesting to have the insight into Carla’s thinking. So…is Wolverine “there to see”?

I don’t really know. I mean, I definitely sympathize with you being sick of Wolverine, but I don’t really think there’s a whole lot to Wolverine. As much as we’re talking about “archetypes” here, ol’ Wolvie himself isn’t one; he’s not really any kind of cultural source code, he doesn’t go back to prehistory or anything like that, he just goes back to John Byrne liking Clint Eastwood movies and Chris Claremont liking Lone Wolf And Cub. So for me, Wolverine doesn’t ruin anything except Wolverine. Even if I hated that Thor movie, it wouldn’t mean I’d stop liking Norse mythology? It’s kind of like that. For me.

For me and my two cents.

Aw, MAN… deny, deny, deny. More experienced writers keep telling me ‘deny everything’ and I forget. No cult of personality for me.

I’m loving the first volume, Carla!

You’re far too self-aware to inspire a cult of personality, Carla. Bless you for that.

I enjoyed the review and responses it generated, but…

Comparing Jaeger to Wolverine seems about like comparing Atanarjuat to Steven Seagall whispering mumbo-jumbo in a beaded,buckskin shirt. Also, throughout Finder, it has always seemed clear to me that Jaeger is 5th business?

These things have been said already, just wanted to echo them. thanks

I really, really want to like this author’s work and the parts that I do enjoy make the parts that I don’t enjoy all the more irritating; thanks for summing up part of the reason why I’m experiencing those feelings.

She admits to being derivative, but I find it is still copying too many obvious sources for me to stay immersed.

I quite liked Voice, as did another writer here — you can click on McNeil’s name in the tags. and find some more discussion of her work on the site.