This morning on Twitter Steve Cole expressed concern that scholarship would ruin comics.

If comix become scholarship, @comicsgrid, do you not diminish their value? You can study good stuff to death yaknow. Overthinking KEEP OUT!

The good folks at the scholarly website Comics Grid responded by insisting that rather than subtracting from comics, scholarship advocates for (and presumably therefore adds to) comics value.

.@earth2steve why would scholarship diminish comics’ value? On the contrary, comics scholarship is all about advocating comics’ value.

It’s a familiar dialectic…and one which I wish comics could divest itself of.

The base assumption for both Cole and the Comics Grid is that (a) comics have value, and (b) that value has to be protected, or at least highlighted. As critics, as readers, our goal is to preserve and celebrate the greatness of comics as an art.

The problem with this logic is that most comics are crap, and to the extent that anyone values them, those people should be mocked — or at least, you know, gently disagreed with. Comics itself, as a form and a history, is, for that matter, not particularly glorious. I have affection for comics, but if you wanted to make the argument that comics value was low enough that diminishing that value didn’t really matter and advocating for it was silly — well, I don’t know that I’d have a particularly effective defense.

You could say some of the same things about academic scholarship, of course. Much of it is badly written and badly thought through. But whether scholarship is good or bad has little to do with whether or not it adds value to the art it’s analyzing. Some of the scholarly writing I’ve most enjoyed is dedicated to ruining art — Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, for example, which chops up Hollywood cinema in an avowed effort to destroy it. On the other hand, critical writing devoted to advocacy can be pretty boring and pointless (though of course, it doesn’t have to be).

For me, anyway, critical scholarship affects me much the way art does; it can be beautiful, inspiring, exciting, ugly, dispiriting, or dull, depending on form, content, and the way the two coalesce or diverge. Part of the affect/effect is the way that the criticism glances off art…but that’s true for comics as well. I probably wouldn’t despise the vast majority of Wonder Woman comics quite so much if Marston/Peter weren’t so much better. Similarly, Christopher Reed’s Homosexuality and Art rather knocks the stuffing out of avant-garde pretensions, which makes Jackson Pollack, for example, look a little silly and pitiful — but so it goes. I’m sure Pollock’ll manage somehow.

In short, the value of art isn’t some inviolable deity that we have to genuflect to. If thinking about or even ridiculing a comic diminishes its value, then diminish away, I say. Thought and ridicule both have value in themselves, surely. And if your comics are so delicate that you need to be constantly hovering over them or touting them in order to preserve their aura, then I’d suggest that it’s maybe time to invest in some new icons.

“if your comics are so delicate that you need to be constantly hovering over them or touting them in order to preserve their aura, then I’d suggest that it’s maybe time to invest in some new icons.”

YES SIR

I have 4 bagged issues of Todd McFarlane’s Spiderman 1. They have no value.

My issue of Lidsville 1 has a lot of value to me. For the lonegst time i thought i had dreamed that show. but when I found that comic at a “con,” in a Knights of Columbus hall, I knew it was real. Comics has shown me that dreams can come true.

There was a time when I read Clowes’s “LIke A Velevt GLove” over and over, like a dozen times in a row. I think of that time as valuable to me, though I get that others might say: “THat is of no vlaue to me.” I might be forced to agree that it has no vlaue . . . to THEM.

in the days bfore we all had computors, i searched heaven and earth for Brother power the geek number 2. when i found it i was elated. yet this joy was soon repleaced with the despair that follows all such achevments. If “all is vnaity” wouldnt that mean comics is vanity too? yes, I am sad to say.

Wuold you say to a little girl who was sad for Chalries Brown: “You must know comics has no value.” I fear you would.

Just because something is the opposite of what is said on twitter does not make it true. even though it often is. We cant always be sure.

I don’t think Peanuts and comics are the same thing.

But…sure. I tell my kid Santa Claus doesn’t exist all the time. He won’t believe me though.

ok then Mr. Nitpicky. PEANuts has given many people joy and consolation. these are values. Why do you hate that which brings joy?

no snappy response to my lasy volley?

I love Peanuts. I think individual works of art can be valuable. Other works of art are evil and should be destroyed.

And sometimes that which brings joy is lovely, sometimes not so much. Nationalism brings joy to lots of people; does that necessarily make it good? Bullies get joy from hitting their peers. Does that mean we shouldn’t criticize bullying? I’m sure some people get joy from In the Shadow of No Towers…but they should be disabused, by god.

“I tell my kid Santa Claus doesn’t exist all the time. He won’t believe me though.”

Love it.

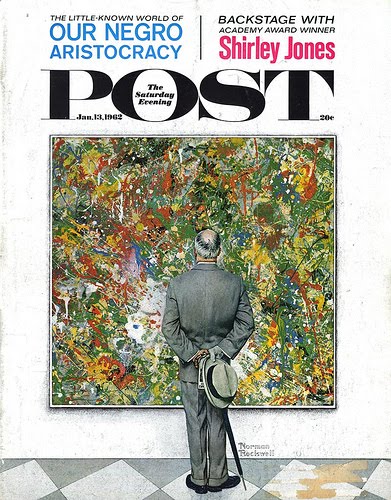

Off topic, but I have mixed feelings about that Rockwell picture. It’s funny, but if it’s trying to look specifically like a Pollack, it’s missing the point. Bill Burroughs supposedly called Pollack “The old Lace-Maker,” and indeed Pollack distributes colors more or less evenly, rather than in random clumps a la Rockwell.

Back on topic ( I hope) one might argue that scholarship can bring value or lack thereof to the attention of interested parties. Sometimes when I’m nonplussed by a work I peruse a few scholarly articles in search of a toehold; sometimes it even pays off.

And if one believes (as I think I do) that things like “meaning,” “value,” and “merit” are (at least partially) cultural constructs, then the idea that scholarship can create value becomes a serious possibility.

If the issue is cultural cachet, criticism can definitely have an effect — though not always positive. Wertham crippled the comic book industry both culturally and financially. I think that debacle is part of the reason that comics remains so leery of criticism (even more so than other arts, which often aren’t especially fond of criticism either.)

Even more than Rockwell’s painting, I’m intrigued by the little-known world of OUR NEGRO ARISTOCRACY.

How would you go about demonstrating that a liking for A SHADOW OF NO TOWERS is as harmful as a nationalist urging his country to go to war (my example) or a bully taking joy in someone else’s pain?

Hey Gene. Not sure where I said it was as harmful. I just was pointing out that joy in and of itself is not a surefire indicator of goodness or virtue. The Shadow of No Towers sentence is kind of a joke, you know?

I did really and truly hate that book though. My review is here.

The Shadow of No Towers lacks substance,not just metaphorically either.

“This is the story about Jack and the Glory,

now the stories begun,now the stories done.”

Sorry, I assumed that since your other two examples dealt with the harmful consequences of joy-inspiring behavior, you just might be drawing a parallel to the third kind named.

Question remains, though: in what way is the joy of a reader for NO TOWERS dubious? Does it have some consequences? Even with a joke, I should think there would be a reason behind the ribaldry, a method behind the madness.

I was making a parallel. That’s difference than an equivalence.

And I talk a fair bit about what I think the social/political implications of shadow of no tower are in my essay. You can read it or not, as you wish.

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/Comics_Academics.jpg

(And no, I’m not saying there’s no “sweet spot” beyond arrogantly clueless, Theory-spouting academese and “Rob Liefeld is God” fanboyishness…)

It’s nice to meet the good ol’ anti-intellectualism of the comics milieu again from time to time…

Noah, you’ll be first against the wall when the comics scholarship revolution comes. Also, never mind the Pollocks, I want to know more about our secret Negro aristocracy.

a propos Shadow of No Towers: last year, as you all know, was the tenth anniversary of “September 11”. My friend held a Bad Taste party the night of 10 September, a fancy dress party with the theme of, well, bad taste. One guy went as a tampon (all white, rope around his waist, dyed his hair red), another woman went as the Jonestown massacre (she walked around with a glass of kool aid; occasionally she’d put a few potato chips in her mouth, take a swig of the kool aid, and bring it back up as a foamy, frothy mess that oozed out onto her T-shirt). My wife and I went as “9/11”. We cut some model planes in half and stuck one half onto each of us; she made a little explosion, with flames and smoke, out of crepe paper that we stuck on where the planes were “flying into” us; and for our coup de grace we hung with string, from various places on our torsos, a bunch of little plastic figures (army figures with the guns cut off), upside down as if falling out of the towers. At the stroke of midnight, she dramatically fell to the ground and, shortly after, I followed.

Beat that, Spiegelman.

And Jones wins the thread.

——————-

gene phillips says:

Question remains, though: in what way is the joy of a reader for NO TOWERS dubious? Does it have some consequences?…

——————-

Dubious ’cause the book (which I’ve got a copy of) is absurdly overproduced, with nary a whit of import, thought or substance behind it…

(I’m reminded of a “Little Annie Fanny” spoof. Alice Cooper is showing off the lavish packaging of his latest record: all black leather, with a zipper in front; when you open the zipper, you can pull this long tongue out! Annie sez, “But what about the record?” Alice is horrified: “Oh, my God! We forgot to put in the record!“)

…and finding “joy” in it is as dubious (in terms of indicating unformed, unsophisticated, or weirdly “off” tastes) a reaction as finding a Hooters Girl the epitome of womanly sexuality.

The consequences being, that readerly and/or critical acclaim would encourage, rather than punish, such balderdash; thus likely lead to more crud along those lines being produced.

(Spiegelman couldn’t even finish the book! He resorted to bumping up the page-count by reprinting old comic strips as filler, with the dubious excuse that reading those strips was a comfort to him and his wife after the trauma of 9/11. Why not insert a gift certificate to Baskin-Robbins instead of added chapters, ’cause eating ice cream is a comforting experience too?)

Not that the book is utterly worthless; but am also reminded of the critical reaction to the lavishly produced, ultra-expensive film of “Cleopatra” starring Liz Taylor: “The mountain has labored, and brought forth a mouse.”

——————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

It’s nice to meet the good ol’ anti-intellectualism of the comics milieu again from time to time…

——————–

Yes, because mocking “arrogantly clueless, Theory-spouting academ[ics]” is being anti-intellectual. Just like criticizing George W. Bush or being opposed to the Iraq war or Abu Ghraib means you “hate America.”

Because George W. Bush is America; and know-it-all academics who see comics via the distorting mirror of their absurd pet Theory are intellectualism.

No other, more reasonable, varieties of America or intellectuality must be considered to exist; or else…the terrorists win!!

(Which is why I’m forever quoting dictionary definitions: because those who control what a word is thought to mean — or push a single narrow description in lieu of a multifaceted complexity — control discourse. If “liberal” is considered to mean an America-hating, atheist Muslim fundamentalist who wants to force our kids to marry homos, instead of someone who is tolerant and open-minded, well…you might as well give up and call yourself a “progressive”!)

See “Fashionable Nonsense: Postmodern Intellectuals’ Abuse of Science”: http://www.amazon.com/Fashionable-Nonsense-Postmodern-Intellectuals-Science/dp/0312195451 , http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fashionable_Nonsense . The latter containing gems of postmodern philosophy such as Luce Irigaray’s assertion that E=mc2 is a “masculinist” equation.)

(One can imagine the reaction: “Now you’re against philosophy!“)

And, you don’t have to go to Academia to get arrogantly clueless pronouncements: check out Pauline Kael’s book on “Citizen Kane,” where she, with the agenda of putting Orson Welles “in his place,” — with little evidence or idea of how films are done in the real world — maintains the cinematographer suggested some shots and camera angles to the director, who humbly complied. (Andrew Sarris’ deconstruction of Kael on Kane at http://www.wellesnet.com/?p=1320#more-1320 )

Mike, your piece would be funnier and more pointed if it engaged with something vaguely similar to something some academic had ever said. As it is, it just comes across as silly straw-manning…and as a exercise in nerd-upmanship, since the point your discussing seems really obscure.

I mean, unless you saw some academic say that somewhere? Maybe a citation would be helpful…?

I’m afraid I’m not immersed enough in the milieu to come up with as something jaw-droppingly nutso as “E=mc2 is a ‘masculinist’ equation.” Compared to the things some academics and “philosophers” actually say, my cartoon folks’ argument makes some oddball sort of sense.

(Note that what I had Comic Book Guy object to was not their premise, but their assertion that the function of inked borders was such-and-such. If they’d made the argument that, unwittingly, those lines-around-figures created a symbolic “separating” effect; well, that’d be another story.)

My point was, though I’m emphatically in favor of serious, thoughtful scholarly looks and analysis of comics, especially by people who bring broader perspectives and knowledge to the job, when people who force art into the Procrustean beds of ideology or philosophy turn their attention to comics, the results won’t be pretty.

I mean, look at what happens when some writers are handed a job writing about comics, simply because they are a “Name,” not because they have any particular knowledge or understanding of the art form…

My ideal would be someone like Borges; incredibly erudite and well and widely-read; able to appreciate the depths in what other intellectuals would dismiss as ephemera, such as Chesterton’s Father Brown mysteries; not trying to force works into a prescribed ideological framework; perceptive and incisive in his criticisms. (Not that I agree with him throughout; but he can be a bolt of lightning illumining a landscape.)

Check out the dazzling “Borges: Selected Non-Fictions”: http://www.amazon.com/Borges-Selected-Non-Fictions-Jorge-Luis/dp/0140290117 …

Noah, your specific reasons for disliking SHADOW don’t bear on the topic, so I’m not dipping into them here. Since the thread is about the effects of scholarship and criticism on the “value” of comics, I’m trying to get at what ends are served by criticism.

For instance, you say (responding to Aaron I think):

“Wertham crippled the comic book industry both culturally and financially. I think that debacle is part of the reason that comics remains so leery of criticism (even more so than other arts, which often aren’t especially fond of criticism either.)”

I don’t want to get off the tracks talking about Wertham, but he is emblematic of the type of critic who finds “harm” in a particular type of entertainment. Whether it is or isn’t is of course a separate argument.

I asked whether you were stating that SHADOW was harmful in a manner analogous to the other two processes you mentioned. If you had been saying that, without any irony whatsoever, you would have been allying yourself with the “if this is allowed to go on” crowd, in my opinion.

It’s impossible to write anything, fiction or nonfiction (which includes criticism), without hoping that it has an impact on someone who reads it.

It’s facile, though, to hope that it will have that impact on *everyone,* which is very much the intention of the “if this is allowed to go on” crowd.

Right; you’re confirming my point. Wertham criticized comics from a moral perspective and damaged the form; therefore any suggestion that comics might be judged from a moral perspective must be attacked.

Shadows glibly turns 9/11 into a tragedy of universal import (more or less mocking people in middle america who don’t see it as sufficiently important.) It links it to the Holocaust iconographically. I think that’s simple-minded and dangerous, and should be mocked.

He also makes excuses for early 20th century racism, which I think is kind of heinous. And the book’s a giant and deliberate rip-off.

Does any of that mean it should be censored? No. But it does mean that I don’t have any qualms about ruining it for somebody, or lowering its value. If I could lower its value by pointing out its idiocy, that’s all to the good as far as I’m concerned.

I think Wertham’s criticism is often, or at least sometimes, fairly thoughtful. His discussion of queer content in WW is perceptive, for example, though obviously I wish he weren’t such a homophobic asshole.

i never get used to how much you hate comics and I never stop being baffled as to why, with such loathing, you decided to run a comics blog. I often veer away from this site, put off by the vitriol and condescension, as well as the smug elitism. I don’t mean elite, as in scholarly, I mean the cheapest elitism, the adolescent sort that decrees the tiny circle of what is right, and protects it’s sense of worth by excluding most everything, especially anything that has any traction with people.

scholarship is not for the purpose of elevating or promoting–though sometimes that is a by-product. It is for exploring, understanding, comparing, etc. Comics, whether they are crappy or not, have been a cultural force, they are a mass media communications medium, they are artistic expressions, and they are somewhat unusual in that they blend pictures and text. As far as content goes, or genre, they do cover the entire spectrum of expression. This is an essential truth no matter how big the gap in popularity between superheroes or funny animal books and everything else is.

As long as our society is wealthy enough that we can devote a segment of the population to reflect on abstract things, there is no good argument not to devote some of this energy to studying comics, and this also includes historiography and curation.

your hatred of comics seems to rest on maintaining a shifty and personal definition of comis, and how easy a position it is to have since you have a very flexible definition of what a comic is, perhaps even as simple as ‘comics i like aren’t comics, and comics i dont like are’. i can see no other reason for your flippant statement about peanuts.

I often see you deflect criticism by saying you were being facetious, jocular or lighthearted, but you are engaged in comics criticism and you make these sorts of statements that sound quite earnest, but are dropped in ways that can be brushed off if you are called on them, the way you have with your inclusion of shadow of no tower in a sentence with far more decidedly toxic things. it’s easy to be polemical, if you can just follow it up with ‘lighten up’. Should we take a comics journalist/essayist seriously who constantly sneers down his nose, makes blanket condemnations and mocks the very subject he professes to be his calling?

I don’t think most comics are crap. I also question at this point if superhero comics(which do seem to have lost their joy and become tedious–i wonder what kids would say) are most comics. they have very small circulation. Either way, they are an interesting facet of culture to turn a scholarly eye on, just like children’s humour comics, war journalism comics, surreal comics, or boundary pushing raucous comics. Some comics appeal more to children, some to adults, some to the childhood spirit in an adult. some are escapist, some are scathing social commentary, some simply transgressive, some warm and touching realist stories. I don’t see much truth or justification for the way the authors of this site regularly make a punching bag and punchline out of comics. You do seem to be a rare species who have all found each other. I don’t think its weird that you think comics are vile, or mindless or trashy. I find it weird that you devote yourself week in and out to saying so.

I ask again why you run this blog since you hate virtually all comics and are quite comfortable making generalized ‘comics suck’ statements on a very regular basis. You also choose essayists who while they don’t generalize as much as you, are just as disdainful of most comics. Who do you imagine your audience to be, or who do you desire for an audience?

Peanuts is a comic which I love. “Comics” is a genre category; I don’t think that category has any intrinsic cultural or historic value (nor do other genre categories, like “poetry.”)

Lots of folks who write here like lots of different comics, and other art too. Look at the featured posts at the moment and there are people praising Homestuck, Gasoline Alley, Dokebi Bride, and Degas. So you could go read those…or you could wait till next month when all your worst fears will be realized.

Oh, this: “Who do you imagine your audience to be, or who do you desire for an audience?”

I’m happy to have anyone for an audience who wants to be here. Honestly, the readership at the moment is way bigger than I ever imagined it would be; I am constantly surprised and grateful.

“I mean the cheapest elitism, the adolescent sort that decrees the tiny circle of what is right, and protects it’s sense of worth by excluding most everything, especially anything that has any traction with people.”

I mean…I rather like Twilight. Surely that counts for something?

i knew it was pointless to comment. you are adept at winking and nodding, the way a politician does. i do enjoy the articles that either take an objective look at something, or whose research and exposition was inspired by joy, not a desire to skewer. but they tend to me in the minority, and i find, the essayists have trouble getting through even the most celebretory article without ribbing and reminding people how worthless most comics are..

by your notion that the term for something (comics, poetry) encompasses all of the things in that category and therefore will contain substandard, or even terrible examples and therefore cannot be said to have value can be expanded to anything. Soil has no value because some of it isn’t fit for growing. Water has no value because some is polluted. Film has no value because some of them make us wince. Your definition of a thing or category precludes anything of being of value. Comics are significant, and they have value. If experts deem something worthless but that thing entertained or engaged people, that thing has value. It has performed work. It has had impact.

I know you are erudite, and well read. I cannot fathom how you could possibly suggest that artifacts that make up history have no historic value. Again, what does have historic value? You brought up Gasoline Alley which is itself an historical document, telling a story of generations of an average american family.

Incidentally, you very specifically said Peanuts is not comics. I wouldn’t normally say this of you, but it feels like you are trolling your own comments section

“I don’t think Peanuts and comics are the same thing.”

I have been known to misread, but… Noah isn’t saying “Peanuts isn’t an example of a thing called a comic.” He’s saying that the thing that is Peanuts and the thing that is “all comics” are not the same. You can say “I like Peanuts” without meaning “I like all comics.” It’s kind of a thing with people in the comics world that you “like comics” as a whole encompassing concept. But no one says “I like music” and means they like every sort of music out there. The comics world is just so small and inwardly focused that people find it too easy to equate “some examples of comics” with “all comics”.

“Mike, your piece would be funnier and more pointed if it engaged with something vaguely similar to something some academic had ever said.”

Oh, just for the fuck of it: though not comics, Mulvey’s gaze article is a pretty good example of taking pro forma techniques and reading them as some bedrock of ideological influence.

Right, Derik’s got it.

I don’t have any desire to defend, elevate, advocate for, or increase the value of comics. It’s a form and a history which can be used for good or ill. There are particular comics that I’m happy to defend or advocate for, though (like Dokebi Bride, which is great.)

Entertaining and engaging people can be good or it can be bad. The Roman circuses entertained and engaged people, but that didn’t make them valuable or worthwhile pursuits for which we should be nostalgic. The Protocols of the Elders of Zion entertained and engaged some people, but, again, that doesn’t mean we need to pat it on the head.

The term historic value is maybe somewhat slippery. Any document is useful for a historian, obviously. But there’s often an argument made by comics critics that the historic value should be converted into aesthetic worth. Comics is a historical genre (or perhaps medium), but I don’t think that that gives comics any particular aesthetic value or merit, is what I was trying to say.

i don’t see the word “all” in the statement. what i read as a clear, concise statement, is that peanuts is not part of the set known as comics. the clear suggestion is it is ok to venerate or elevate peanuts as a cultural artifact, because it is in fact not the tawdry and loathed artform known as comics. he may be being earnest, or facetious–we’ll never know as i doubt his intellectual honesty at this point.

i’ve actually never come across anyone who misunderstood ‘i like comics’ to mean ‘i like all comics’, or even ‘i have a passing familiarity with all comics’.

Noah, again, to repeat myself. no one, no one assumes that every instance of a thing is valuable, or that all instances of a thing are equal. you are making a nonsense argument to prop up your nonsensical premise. “comics”, the good and the bad, are a cultural phenomenon, they are a window in to at least some facets of cultural history, understanding and criticising bad comics, perhaps on an ideological level, is as valid, as examing, understanding and judging roman entertainments. your determination to try and stick by what you (seemingly) wrote off the top of your head is making you argue that cultural forces that are stupid are unworthy of examination, despite the fact that they have influences and that because some examples of a medium are of little or no value that that medium is unworthy of study. scholarship has better things to do than waste its time with a valuless artform that has been around for a century, growing, evolving, changing, influencing other artforms, possibly influencing people’s perceptions (for good or ill, or neither, just influencing).

advocating for scholarship into comics is not advocating comics. it isn’t advocating particular examples of comics or for all comics, or for comics as an abstract term. advocating for scholarship into comics is recognising that there is a thing called comics, people make them, consume them and they have some effect on us, therefore we should stop and look at them critically and reflect.

no one was talking about nostalgia, no one was suggesting some bizarrely narrow binary approach to comics that they are good or bad(other than you). what i don’t understand is you are a scholar and an intellectual, yet you adopt this anti scholastic anti-intellectual stance? There are endless questions we could ask about comics and what people get out of them, what artists and authors are attempting, how much they succeed or fail, what the whole enterpise says about us, where it fits into other arts, where it fits into history, actual logistic and technical questions about writing and drawing and how they are combined.

circling about with this “comics have no value” and “by comics i mean some comics are bad or valueless”, well, its simple, and incorrect use of language and terminology and really strikes me a purposefully obstinate.

Again, more repetition, scholarship is not elevation or promotion, but examination. your argument was to question whether comics inherently–as a a medium, and by the products the medium has amassed over the last century(i.e. the greatest, the worst and those in the middle) had any value to begin with. and you did seem to be coming out on the ‘nope’ end of that question, unsurprisingly.

I really didn’t say Peanuts wasn’t a comic. I don’t know where you’re getting that.

The tweet from comics grid said that scholarship advocated for comics value. I was saying I don’t think it should. That’s all.

Charles…that’s interesting. I don’t know that I buy it, though. She talks specifically about Hitchcock and von Sternberg, two directors who strike me as quite self-conscious, and contrasts the differing ways in which they treat women formally. Since there are multiple techniques she’s talking about, it seems odd to argue that they’re merely pro forma or meaningless neutral formalisms — especially, again, since the directors she focuses on seem pretty aware of what they’re doing.

What in the world are “pro forma techniques”? Techniques that are simple formalities? I have no idea what that could mean. Are you sure you don’t just mean “formal techniques,” Charles? The only way I could make sense of your statement would be something like, “Mulvey takes purely formal techniques and interprets them ideologically.” (And if that’s what you mean, well yes, but she’s right to do so… because nothing is purely formal.) But that’s not what “pro forma” means…

A shot-reverse shot isn’t always a matter of interpellation or an expression of the male gaze. It’s quite often what’s being looked at connected to who’s doing the looking. Confer Melanie Daniels on the boat in Bodega Bay. That would be pro forma.

And taking Hitchcock and Sternberg, with their particular interests, as the structural unconscious of the medium is going to be problematic. As you say, Noah, they were very conscious of what they were doing.

idleprimate, though I agree with many of your arguments, in all fairness I think when Noah writes…

————————-

“Comics” is a genre category; I don’t think that category has any intrinsic cultural or historic value (nor do other genre categories, like “poetry.”

————————-

…he’s not saying that he hates comics (or even hates then “in general”); I believe his argument is that an art form in and of itself, has no inherent value. The art form serving in the same fashion that a generic container; the content is what is all-important.

(Dunno why instead of art form he uses the “genre category” term, which for me muddies the waters. When most hear “genre,” we think Westerns, SF, horror, comedy…)

Earlier, Noah wrote:

————————

The base assumption for both Cole and the Comics Grid is that (a) comics have value, and (b) that value has to be protected, or at least highlighted. As critics, as readers, our goal is to preserve and celebrate the greatness of comics as an art.

The problem with this logic is that most comics are crap, and to the extent that anyone values them, those people should be mocked — or at least, you know, gently disagreed with…

————————-

Surely we’ve all heard of Sturgeon’s law, “…an adage commonly cited as ‘ninety percent of everything is crap.’ ” ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sturgeon%27s_Law ). Though I’d not be quite as harsh, it’s hard to disagree with the basic premise: that junk far outweighs quality.

Now, those folks who maintain “the art form of comics has to be protected from negative criticism” seem to be mentally in that time when, indeed, the vast majority of the public and intellectuals considered comics not to be of “no inherent value,” but worse. Inherently rotten: simple-minded, glamorizing criminality, etc. (I’m reminded of the popular catchphrase, in the heyday of the Civil Rights struggle, “Black is Beautiful.” An extreme antithesis to the attitude widely held, that black was ugly: immoral, criminal, lazy, unintelligent.)

However, these days (after a great deal of work by comics defenders, and year after year of worthy comics from “Maus” to “Fun Home” have earned critical acclaim), it is safe to say that most of the public and what passes for an intelligentsia here are perfectly aware, though a lot of comics are junk, that fine work of literary worth can indeed be produced there. That if something is “comics,” it doesn’t have to be crap.

Thus, Noah’s attitude (if I understand right) actually expresses greater confidence in the art form of comics. Cheerfully conceding that most produced there is of little worth doesn’t automatically mean that everything in comics is crud. (Transferring that to Civil Rights, it would be like saying, “Blackness is neither inherently beautiful nor ugly; it’s up to the individual person to be that way.”)

“It’s quite often what’s being looked at connected to who’s doing the looking.”

But…that’s kind of her point. Who’s looking, what they’re looking at, and how they’re connected has ideological content. The fact that Hollywood structures the gaze in a particular way isn’t non-ideological, as Andrei says.

“But there’s often an argument made by comics critics that the historic value should be converted into aesthetic worth.”

A good point. I think it’s important to differentiate comics works that are of historic value for various reasons (influence, innovations, etc.) and those that have aesthetic worth. The latter is more objective. I can certainly accept the historic value of a lot of the (so-called) “great” comics, but I don’t always accept the aesthetic worth of those comics. Crumb and Kirby are two good examples, in my case. I get their historic value, but I don’t find their aesthetics to my taste (nor in many cases the people who were heavily influenced by them).

“i don’t see the word “all” in the statement. what i read as a clear, concise statement, is that peanuts is not part of the set known as comics.”

Perhaps the confusion comes from the grammatical weirdness of the word “comics” (plural/singular usage)… but if you want to get literal, I don’t see the words “part of the set known as comics” in Noah’s statement either.

He didn’t say “Peanuts is not a comic.” He said that “Peanuts” and “comics” are not the same thing. Look over there is Peanuts, a single series of comic strips. Look over there is the very large conceptual category that is comics. See how they are not the same thing? Single work (a comic strip series). Category/form/genre/medium (whatever you prefer to call).

Oh…I get it, he was misinterpreting the “Peanuts and comics are not the same thing” quote. Thanks Derik…and of course you’ve got it right.

“i’ve actually never come across anyone who misunderstood ‘i like comics’ to mean ‘i like all comics’, or even ‘i have a passing familiarity with all comics’.”

I think this is really common. Not that people like (or know) every single comic in existence, but that they in general like “comics” as a generic form/category/medium. It relates greatly to the “team comics” conception, which I think is part of the original impetus for Noah’s post, that we, the comics world, is all in this together to promote/advance “comics” in general as respectable/worthwhile/art/not-just-for-kids/valuable/etc. Which is mired in a strong historical vein of comics being low/disrespected/trash/etc.

“But…that’s kind of her point. Who’s looking, what they’re looking at, and how they’re connected has ideological content. The fact that Hollywood structures the gaze in a particular way isn’t non-ideological, as Andrei says.”

No, when the female gaze was pointed out, she suggested it was actually a transvestite gaze.

Let’s be clear: there’s a difference between saying form can never be ideological and that it doesn’t always serve a particular ideological function. Andrei ambiguously said, “because nothing is purely formal.” But I never said anything was purely formal, only that the use of many techniques is pro forma (standardized, conventional). The shot-reverse shot more often than not simply gives you the content of what’s being looked at and by whom, which doesn’t signify a universalized male gaze. It has content (isn’t purely formal), but isn’t easily reducible to just one message, indoctrinating you as you look.

That’s a much different argument than the one Mike is making in his cartoon, though. You’re saying that Mulvey has misread the formal structure — that is, she’s not contextualizing it sufficiently. (Which she actually agreed with at some points later in her career, I think.) Mike’s cartoon strongly suggests that the mistake is in attributing content to formal techniques at all.

Hmm, I didn’t take him to mean that, only that the pointy heads jumped to the radical interpretation instead of a simpler one.

“Right; you’re confirming my point. Wertham criticized comics from a moral perspective and damaged the form; therefore any suggestion that comics might be judged from a moral perspective must be attacked.”

See, the way you phrased that, it too sounds ironic. But from the context, it sounds like you mean it literally. Which is the case here?

I don’t object to some moral parameters in criticism, but I don’t regard literature as principally a source of moral guidance, so I disagree fundamentally even with those critics who responsibly emphasize its moral nature, like John Gardner and Wayne Booth. (Wertham isn’t in that category as he was an irresponsible moral guardian, with no real conception of the issues on which he fulminated.)

I guess I’m not getting the original context of “value” here. Usually, by the time some work has become deliriously popular with some audience, whether it’s SPAWN, MAUS, or JONATHAN LIVINGSTON SEAGULL, critics who don’t like those things can’t affect their marketplace value. All they can do by then is piss and moan about how they shouldn’t be popular– or at best, grind their knives for the next Bruce Willis or Kevin Smith movie and endeavor to keep THAT from being a financial success.

Is that anything comparable to the way you’re using “value?”

I think you did in fact confirm my point about Wertham.

I think the sense of value that I got from the tweets was that critics could damage people’s experience or enjoyment of the work. Perhaps a secondary worry that the works commercial fortunes might be harmed.

I think critics can do both those things, in some cases. Reading a negative review can make you reassess your liking for a work; negative criticism can damage popularity, too, though of course that’s more difficult. I don’t see why there’s anything wrong with either of those things happening.

You seem to be working from a point of view where critics are somehow clearly distinguished from the public, incidentally. I don’t think that’s true now, if it ever was.

“scholarship is not for the purpose of elevating or promoting–though sometimes that is a by-product. It is for exploring, understanding, comparing, etc. Comics, whether they are crappy or not, have been a cultural force, they are a mass media communications medium, they are artistic expressions, and they are somewhat unusual in that they blend pictures and text. As far as content goes, or genre, they do cover the entire spectrum of expression. This is an essential truth no matter how big the gap in popularity between superheroes or funny animal books and everything else is.”

I would tentatively agree with this, in that I too define art primarily in terms of its expressive capacity, with its capacity for moral guidance or technical excellence chiming it at secondary and tertiary levels (if not lower).

“I think you did in fact confirm my point about Wertham.”

OK, I guess you were making that statement seriously. It sounded odd to me in part because you had criticized Spiegelman for letting old racist comics off the hook. I would regard that as having made a moral judgment of Spiegelman, rather than an aesthetic one, as seen in this statement:

“But there’s often an argument made by comics critics that the historic value should be converted into aesthetic worth.”

The thing is, how does one determine whether or not items of historic value should or shouldn’t have aesthetic worth, except by using the tools of scholarship and criticism, whether one argues in terms of morals, aesthetics, etc.?

I would agree that are bad scholars out there, as you state, but I don’t think we’re in great danger of having pure historicism overwhelm aestheticism. The Woman in Red is heralded in some quarters as the first costumed superheroine, but even among populist scholars, who cares? Wonder Woman and even Sheena are still more fun to write about.

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…Mike’s cartoon strongly suggests that the mistake is in attributing content to formal techniques at all.

—————————–

To get finicky (for a change), it’s not so much that they attributed ideologically-oppressive content to what are simple technically-necessary production techniques…

…rather, it’s that they assumed the ideological oppressiveness was the raison d’être of the technique, rather than an incidental, accidental feature.

I actually oversimplified those techniques. Of course, with the poor paper stock and production techniques involved for most comics, it was necessary for pencil drawings to be inked over, even in b&w comics. Else much of pencil art would “drop out.”

And, if one wishes, that technical necessity could also be seen as a part of the capitalistic industrial system in action. The original artist’s rendering effaced by inking over and erased, usually by other hands; others lettering, still others coloring. So that the comic story becomes an assembly-line product, the one putting the “team” together legally the creator, the original artist reduced to a mere cog in the machinery, and more replaceable.

—————————-

Charles Reece says:

Hmm, I didn’t take him to mean that, only that the pointy heads jumped to the radical interpretation instead of a simpler one.

—————————-

As even Freud noted, “sometimes a cigar is only a cigar.” And “ideologivision” leads to seeing sinister motivations in what may turn out to be morally-neutral events.

If one sees (a fair enough argument, correct for the most part) society as significantly invested on the exploitation and oppression of women, it’s a common mistake to then assume that women are thus universally despised and held in contempt. That those oppressing them (say, a paternalistically-controlling Hubby) can have no positive emotions towards them.

So that even bits of old-school courtesy such as holding doors open for “ladies” is interpreted by some radicals as showing condescension; implying that women are incapable of opening doors.

And surely heroism in the midst of a recent tragedy, from the point of view of a fervent ideologue, could likewise be twisted as examples of controlling paternalism, possessiveness:

“‘Dark Knight’ Shooting: 3 Boyfriends Die Shielding Girlfriends During Aurora Massacre”: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/07/23/aurora-shooting-boyfriends-died-protecting-girlfriends_n_1695290.html

BTW, there was a point in my choosing Comic Book Guy rather than, say, a Photoshopped-in Gary Groth to make the opposing argument. CBG, for whatever knowledge of comics history or production techniques he may possess, is a doofus with aesthetically-retarded tastes; who knows bupkis about culture beyond superhero comics.

Yet in this instance, he knew far more about what he was talking about than the Pompous Ones. Who blithely dismissed his knowledge instead of appreciating the info; looked down upon him for lack of academic credentials, where in this instance they were the ignoramuses.

Indeed, in academic publications featuring writing about comics, would someone who may have written intensively and perceptively about comics for decades yet lack impressive-sounding degrees, be “invited aboard”? Or be as facilely dismissed as in my cartoon?

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…I think the sense of value that I got from the tweets was that critics could damage people’s experience or enjoyment of the work.

—————————–

A fair enough deed, if they’re accurately pointing out ways in which the work is mediocre, derivative, achieves its effects dishonestly, etc.

…No fair dispensing “spoilers,” though!

Mike: do you see a fair representation of David Kunzle, Donald Ault et al in your cartoon? The reason why fans aren’t very good scholars is because they usually don’t go over hagiography and archivism. When you say: “they assumed the ideological oppressiveness was the raison d’être of the technique, rather than an incidental, accidental feature.” The problem is that what you call “an incidental, accidental feature” was provoked by the ideological oppressiveness (making money churning out product for the masses with cheap production values, no creators’ rights whatsoever, and a rigid set of expressive rules) hence creating the social meaning attached to it in this particular context.

Noah:”at the moment and there are people praising Homestuck, Gasoline Alley, Dokebi Bride, and Degas.”

Marco Mendes too.

I think there’s a fundamental confusion that is fuelling this debate. The confusion of scholarship with criticism. They’re two distinct disciplines, although intertwined on many levels.

That is, scholarship by simply choosing the subject of study oerates de facto criticism; and a good critic should have scholarly knowledge of his subject.

My earlier comment and cartoon:

———————-

Mike Hunter says:

http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/Comics_Academics.jpg

(And no, I’m not saying there’s no “sweet spot” beyond arrogantly clueless, Theory-spouting academese and “Rob Liefeld is God” fanboyishness…)

———————

———————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

Mike: do you see a fair representation of David Kunzle, Donald Ault et al in your cartoon?

———————–

Oh, was I supposed to be ridiculing those specific people? Seems t’me it was just general attitudes by certain cliques being poked at.

————————-

The reason why fans aren’t very good scholars is because they usually don’t go over hagiography and archivism.

————————-

Sure, fans “usually don’t go over hagiography and archivism.” But, what I’m mocking and dubious about — in that cartoon and comments — is not the study and research of scholarship, but “Theory-spouting academese”; the dismissal of technical realities because they don’t fit ideological parameters.

—————————

When you say: “they assumed the ideological oppressiveness was the raison d’être of the technique, rather than an incidental, accidental feature.” The problem is that what you call “an incidental, accidental feature” was provoked by the ideological oppressiveness (making money churning out product for the masses with cheap production values, no creators’ rights whatsoever, and a rigid set of expressive rules) hence creating the social meaning attached to it in this particular context.

—————————-

So, you’re arguing that inked outlines delineating comics figures — rather that a technical necessity for coloring and printing via the low-budget methods used for comics — are actually “provoked” by ideological oppressiveness?

Does that mean that in a world where comics were developed and became popular in a righteously egalitarian, nonexploitative society, penciled drawings would reproduce crisply on cheap pulp paper, colorists cutting overlays (which I have done, if not for comics) would have no trouble “trapping” tones within the often smudgy edges of penciled figures?

If comics artists and designers had creative freedom way back when they could have used lithografs, work in black and white with xylographs (à la Masereel), do direct color, etc. etc… They also could, of course, find the cheap production values of commercial comics appealing (I love ben day dots, for instance), but that would have been their choice, not some imposition from some system in a “factory of ideas.”

Mike: “Oh, was I supposed to be ridiculing those specific people? Seems t’me it was just general attitudes by certain cliques being poked at.”

If you’re not attacking comics scholars, what’s the point? I gave you two names and I could give you many more. I can asure you that none of them looks down on fan scholars because they don’t have a degree.

Oh, if satire doesn’t attack certain specific individuals, then there’s no point to it?

And you keep bringing up “scholars,” while I repeatedly say it’s “Theory-spouting academese” that is my target.

Apparently at least one other person has heard of that attitude:

—————————

From the perspective of a third-generation professor, I confidently assert that the general run of American academics do not believe in hiding their lamp, however tiny, under a bushel. They strut their degrees, snicker at “outsiders,” and bully — by humiliating, marginalizing, snubbing, ignoring– those who attain their expertise in unconventional ways and learn despite “differently wired” intelligences. In the process, they leave behind lasting scars and robust popular prejudice against the value of an education, cultivation, and book learning…

—————————

http://foxywiththetruth.me/2011/11/01/the-arrogance-of-academia/

If you don’t know anyone who behaves like those in your cartoon you’re just giving a voice to a stereotype. A few bad experiences by some students who weren’t even studying comics doesn’t help your case.

————————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

If you don’t know anyone who behaves like those in your cartoon you’re just giving a voice to a stereotype.

————————-

So if someone doesn’t focus on a specific individual who acted in a noxious fashion characteristic of a group — macho fratboys, Ku Klux Klansmen, nerd-harassing jocks, women-trampling religious fundamentalists, hypocritical Bible-thumpers, corrupt “law n’ order” politicos — therefore it’s only shameful stereotyping that’s involved? And one should lay off the criticism?

If anything, all this “focus on individuals” serves to get the system, larger forces at work that encourage and reward bad behavior, off the hook. Look at Abu Ghraib; it wasn’t the structure and dictates that were rotten, said the apologists; it was all the fault of “a few rotten apples”!

————————-

A few bad experiences by some students who weren’t even studying comics doesn’t help your case.

————————-

Because if they’d been studying comics, then the academic arrogance described (hardly a rare phenomenon; indeed, infamously well-known) would instantly change to sympathy and respect?

No, it would at least put some meat in your straw men and straw woman.

I’m at a loss to think of an intellectual community (whether it be academics, comics readers, baseball fans, whatever) that isn’t defined by its jargon, isn’t somewhat suspicious of outsiders, and doesn’t have more than its fair share of people who think they’re smarter than everybody else. I’ve had jobs outside of academics and its the same stuff. Actually, I think my experiences going to comic conventions prepared me for academic conferences, at both are populated by groups that tend to value obscure texts, traffic in arcana and rarified terms, and feature members with strong opinions and a tendency to air them to whoever will listen. And yes, I’ve been guilty of all of these behaviors.

I’m glad to know that Mike found the target of his satire, after all…

One problem with Mike’s target is that comics academics are, compared to lit people or art people, really much less prone to use theory — especially the kind of Freudian/Marxist counter-intuitive text-as-symptom theory that Mike is parodying. I certainly haven’t read everything out there by a long shot, but the only thing I can think of that really goes there is Anne Allison’s Permitted and Prohibited Desires — and she’s an anthropologist, not a comics studies person.

Donald Ault using Lacan on Barks too, but you’re basically right… Comics theory in Academia came from two sources mainly: semiotics and cultural studies.

——————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

No, it would at least put some meat in your straw men and straw woman.

——————-

——————-

Definition of STRAW MAN

1 a weak or imaginary opposition (as an argument or adversary) set up only to be easily confuted

——————–

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/straw%20man

So is the existence of those who spout “Theory-spouting academese” a “weak or imaginary” thing? These folks don’t actually exist, or are exceedingly few and far between, and not as noxious as depicted?

———————

Nate says:

…Actually, I think my experiences going to comic conventions prepared me for academic conferences, at both are populated by groups that tend to value obscure texts, traffic in arcana and rarified terms, and feature members with strong opinions and a tendency to air them to whoever will listen…

———————-

———————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

I’m glad to know that Mike found the target of his satire, after all…

———————-

Doesn’t the fact I featured Comic Book Guy, who is (besides being an aesthetically-retarded doofus, as I’d earlier noted) exceedingly guilty of the behavior Nate lists — indeed, that’s his defining quality — instead of Gary Groth or such, indicate awareness that neither “side” is perfect?

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

One problem with Mike’s target is that comics academics are, compared to lit people or art people, really much less prone to use theory — especially the kind of Freudian/Marxist counter-intuitive text-as-symptom theory that Mike is parodying.

———————–

Well, good for them, then. (Though that “much less prone to use theory” wording sets alarm-bells ringing. Why, that could mean they run their subject through the Theory wringer only 70% of the time, instead of 95%!)

I get the impression your readings are sufficiently widespread to indicate there indeed is a refreshing degree of clear thinking amongst comics academics.

(Though no quantities of what’s “out there”* that has been read are mentioned; are these twenty or thirty comics-academic essays you’re talking about, or four or five, a statistically-insignificant number?)

And when you wrote, “Much of [academic scholarship] is badly written and badly thought through,” are comics academics similarly guilty, or again better than the typical members of the field?

*Is this stuff accessible online to ordinary folks, that we may read it and say, “I was wrong to have thought comics academics to be like their siblings in other branches of academia?”

It’s less than 70% if you’re talking about French theory.

That’s not exactly a good thing from my perspective. The Anne Allison book is great, for example. And one of comics studies problems I think is that it can be theoretically timid. Though Ben Saunders’ Do the Gods Wear Capes is really well written and theoretically interesting (though the theory it uses is not the stuff you don’t like, and is quite accessible.)

The theory, any theory, is not the problem. The problem is how we use it.

Mike, if you’re really interested try finding all the issues of this mag in a library.

Just to clarify, though you all probably don’t need it, I was trying to show that academics hardly have a lock on cliquishness or arrogance. In fact, I’ve experienced both in every field I ever worked in, and at every level of education.

—————-

Domingos Isabelinho says:

The theory, any theory, is not the problem. The problem is how we use it.

—————

Certainly! As is my problem with ideologies. When those become (an example I regularly employ) a Procrustean bed into which mere reality must be stretched or nipped to fit, that’s the danger.

—————-

Mike, if you’re really interested try finding all the issues of this mag [The International Journal of Comic Art] in a library.

—————-

Thank you! No local library carries it, but maybe an inter-library loan might make issues available…