This first ran on Comixology.

________________________

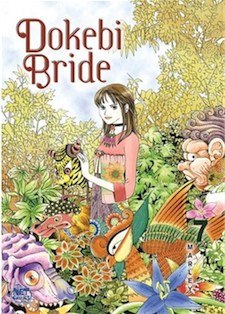

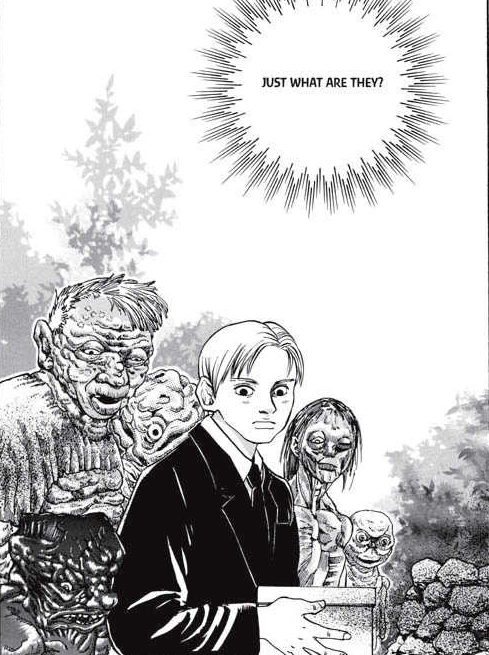

Dokebi Bride is not easy to categorize. A Korean comic, it’s got the young female protagonist, the cute ancillary pet, the fantasy trappings, the giant-eyed waifs, and the flower-bedecked images typical of shojo comics for girls. But, on the other hand, it’s also got gratuitous, gross-out art — twisted corpses, mottled rotting monsters with faces growing out of their cheeks, crawling chattering things with their intestines on the outside — that are more typical of shonen horror comics for boys. The breathtaking covers, with subtle, luminous colors, also seem to reference children’s book art. The whole is one of the most distinctive manga-influenced comics styles I’ve seen, with clean, expressive layouts that juxtapose the lovely and the disgusting, the realistic and the fanciful.

Dokebi Bride is not easy to categorize. A Korean comic, it’s got the young female protagonist, the cute ancillary pet, the fantasy trappings, the giant-eyed waifs, and the flower-bedecked images typical of shojo comics for girls. But, on the other hand, it’s also got gratuitous, gross-out art — twisted corpses, mottled rotting monsters with faces growing out of their cheeks, crawling chattering things with their intestines on the outside — that are more typical of shonen horror comics for boys. The breathtaking covers, with subtle, luminous colors, also seem to reference children’s book art. The whole is one of the most distinctive manga-influenced comics styles I’ve seen, with clean, expressive layouts that juxtapose the lovely and the disgusting, the realistic and the fanciful.

The comics’ approach to narrative falls more subtly, but just as definitely, outside of easy genre categorization. The story centers on Sunbi, a young girl with shamanic powers that allow her to see spirits and the dead. You’d think, given that set-up, that the book might go one of two ways. It could be episodic, with Sunbi meeting and exorcising a series of ghosts in relatively neat, self-contained sit-comish episodes. Or you could have more of a long-form narrative adventure.

Dokebi Bride, though, refuses to plump firmly for either option. Instead, the story keeps shifting in and out of formula; it will establish a group of characters who seem to be the characters, and then it will drop them, sending Sunbi off in another direction entirely. Rob Vollmar, in a fine review of the series’ first volume at Comics Worth Reading, called that book a “prelude,” which it is. But, not having yet read the follow-up volumes, he couldn’t know that everything is prelude: Over the six volumes, Sunbi goes from a child living with her grandmother in the country to a teenager living in Seoul with her father to a runaway living on the streets without ever settling into a rhythm or routine. The book constantly wrong foots her, and the reader as well.

Early in the series, for example, the aforementioned cute ancillary pet — a dog who we’ve seen grow up from a puppy in the first book — leaps between Sunbi and an evil spirit. The dog is badly wounded, and Sunbi is forced to run out into the street. Later, she sees the dog running towards her in a classic Disney moment. “Solbang! You’re okay! I’m so relieved! I’m so —.” But the dog isn’t okay; its dead spirit has just come searching for her. And, to further twist the knife, Sunbi has been placed under magical protection to make her invisible to the spirit world for a time, and as a result, her dog can’t find her. The cute, beloved animal, which in most shojo narratives would be the series’ most identifiable, constant image, goes on into the afterlife in the second volume without ever saying goodbye.

That departure, I think, points to the core knot at the heart of Dokebi Bride. The book, like many ghost stories, is about grief and dislocation and how the two circle around each other like black, exhausted smudges. The first volume opens with Sunbi’s father carrying her mother’s ashes back from the grave; that volume ends with the death of Sunbi’s grandmother, who raised her and cared for her. The central loss of a parent, and therefore of self, returns again and again through the series, a literal haunting. Sunbi can’t function without putting the past behind her, but the past is everything she is — she can’t let it go. When a fortune teller offers to read her future, Sunbi rejects the offer angrily. “No, I don’t want to know about my stupid future!” she bites out through her tears. “Just tell me what all this means to me! Tell me why they’ve all died and left me, why they’re even trying to take away my memories!”

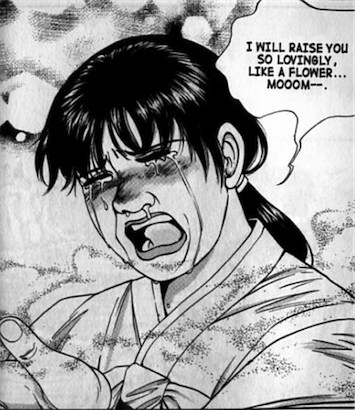

That may sound like a catharsis, and it kind of is. But, again, Marley’s narrative isn’t exactly linear or exactly episodic; instead it’s recursive. Sunbi’s conflict is mirrored on different levels, and in different iterations, in both the people and the spirits around her. In one story, Sunbi meets an old woman from the country looking for her grandson in Seoul; in another Sunbi meets a chef living with her crippled, mute mother, who she appears to hate for her infirmity. Each story ends at an impasse of inescapable, irrecoverable love. The grandmother’s search was precisely and already a year too late before it began; the chef ends the story begging her mother to be reincarnated as her daughter. “I will raise you tenderly, you’re so precious. I will beat up any bastards who make fun of you. So you won’t know any sorrow…so you won’t know any suffering…I will raise you so lovingly, like a flower….” I cry every time I read that. I just cried while writing it, for that matter.

What you’re supposed to do with grief, of course, is achieve closure and move on — ideally in 60 minutes, less commercial breaks. Or, to put it in more eastern terms, as Marley herself does occasionally, too much attachment is a bad thing. Except, of course, and at the same time, it isn’t. Sunbi is constantly being told that she needs to let go, both by people who don’t particularly understand or care about her (like her father and stepmother) and by people who do, like her grandmother. There’s obviously something to this; Sunbi’s attachment to and fears about her past makes her a beacon for unattached spirits, who are constantly trying to possess her. If she’s going to survive, she needs to harden her heart.

And yet, hardening your heart is not necessarily surviving, either. Sunbi realizes this herself, noting, “Grandma told me to live like someone who’s not heard or seen; that it’d be uncomfortable once I got involved in this kind of thing…but…I’m scared that I may not be able to cry, or laugh, if I keep on acting like someone else like this.” This isn’t simply an idle possibility; throughout Dokebi Bride Sunbi shows herself capable of remarkable coldness. When a therapist expresses empathy for the loss of Sunbi’s grandmother, Sunbi responds by using her mystical abilities to first divine and then sneer at the fact that the older woman has had a hysterectomy. This sort of thing happens repeatedly. When somebody tries to get to close to her — whether her father, her stepsister, or a nerdy schoolmate — Sunbi acts like a witch, literally. Sometimes she seems more or less justified; it’s hard to fault her when she uses her mystical connections to take out a number of creepy guys who are threatening her at a club, for example. But the issue isn’t really whether the folks on the receiving end get what’s coming to them, but what happens to Sunbi’s own soul when she reacts from hate and fear. It’s after she has the club guys beaten up that Sunbi first develops a rash on her arm…a rash which Marley clearly implies is a kind of karmic raw spot.

Sunbi defeats her assailants in this sequence by summoning a Dokebi, an ugly goblin spirit with whom Sunbi has a complicated relationship. Dokebi are both powerful and comically hapless. On the one hand, they can cast curses, are physically dangerous, and have access to seemingly limitless gold. On the other hand, they can’t buy anything with their gold because they can’t figure out how to exchange it for money, and they’re so unacquainted with personal hygience that if you smear paint on one, it can’t figure out how to wash it off. Sunbi uses this fact to ensnare her Dokebi, and force him to agree to a contract; she wipes the paint off his face, and in exchange he agrees to come and help her when summoned, aiding her against evil spirits or half-drunk shitheads at a club, as the case may be.

The relationship between Sunbi and her Dokebi is, however, a good bit more complicated than the initial master/servant dynamic would appear to suggest. Sunbi does berate and yell at the Dokebi as if he were an inferior — but for his part, the Dokebi follows Sunbi less for legalistic reasons than for romantic ones. He’s smitten with Sunbi, and while the sexual subtext here is played for laughs, it’s all the more blatant for that. To summon the Dokebi, Sunbi has to lick a ring — and each of those licks has a decidedly pleasurable effect on the Dokebi, who bounces around giggling ecstatically whenever Sunbi’s tongue touches the (ahem) stone.

Just as Sunbi is more than the Dokebi’s master, though, she’s also more than his (parodic) bride. When Sunbi is in trouble, the Dokebi comes and protects her. In a book as obsessed with parental bonds as this one is, that makes him a father-figure. Moreover, when Sunbi asks the Dokebi his name, he tells her he doesn’t have one, and so, as mothers do with children, she names him Gwangsoo, or “hands that shine a light.” No wonder that when Sunbi runs away from home and leaves Gwangsoo’s ring behind her, he falls into a sniveling depression, which is an exaggerated, comic-relief caricature of Sunbi’s own grief at the loss of her parent.

Gwangsoo eventually tracks Sunbi down, and Sunbi greets him gratefully…not so much because he saves her from danger (he actually screws that up) as because she’s happy to have a friend. That reconciliation leads to other, larger ones, as Sunbi seems, at last, to find a balance between protecting herself and caring for others, between holding on to her past and not letting that past consume her. This is a decent thumbnail definition of what it means to become an adult, and by the end of volume 6, Sunbi does, in fact, seem to have grown up.

Or maybe not. Volume 6 ends with a plot-twist that comes out of absolutely nowhere, and leads I have no idea where. I may never find out, either; according to an email from Soyoung Jung, the Vice President of Netcomics, “Dokebi Bride has been “indefinitely postponed…due to the author’s schedule conflict.” That’s obviously really disappointing — but in terms of the series itself, there is a kind of logic to it. Dokebi Bride is definitely a Bildungsroman that never ungs. The issues here don’t get resolved when you reach a certain age; they just change and don’t change. “I have completely overcome my fear of them,” Sunbi thinks near the last volume’s conclusion; a few pages later she’s shouting in terror. The wheel rolls on, and you don’t necessarily get to see where it’s going. Instead, all you can do is watch grief, love, death, and beauty spinning by, familiar and new, no matter how old you are, or how wise you hope you’ve become.

“gross-out art — twisted corpses, mottled rotting monsters with faces growing out of their cheeks, crawling chattering things with their intestines on the outside — that are more typical of shonen horror comics for boys.”

‘Gross-out’ horror has been a strong genre within the shojo demographic for a long, long time – much more so, I think, than is the case with shonen.

Hideshi Hino, Kazuo Umezu, Kanako Inuki, Junji Ito and most of the other significant artists working in horror manga have all serialised many of their works in magazines aimed at teen and/or pre-teen girls and all of them tend to include rather more gore than anything in Dobeki Bride.

That’s interesting. I always thought of Ito and Umezu as shonen artists.

I’m curious, Ian; any other examples of girl coming of age stories with gratuitous gore?

Not much I can think of. Most of the good horror manga released in English (of which there is sadly very little) has been in the form of one shots and short story collections rather than extended, multi-volume dramas like Dobeki Bride. Horror manga (as opposed to romantic supernatural manga) doesn’t sell very well in English so publishers tend not to want to take risks on longer series.

There are various works featuring female leads (e.g. Scary Book, Reptilia and Orochi Blood by Umezu; Presents and School Zone by Inuki; Museum Of Terror by Ito) but I don’t recall any of them really constituting coming of age works. It’s been a few years since I’ve read any of them though so I might be forgetting some pertinent short stories. As for Hino, he pretty much always seems to use male protagonists regardless of which magazine he’s writing for.

Incidentally, you can see previews of Scary Book, School Zone and Museum Of Terror, – not to mention the faux-shojo Octopus Girl (a wonderfully scatological homage to / affectionate parody of Umezu’s stuff) and Lullabies From Hell by Hino (can’t remember if that’s one of his shojo ones or not) – over at Dark Horse’s site.

The sci-fi horror series Alien Nine is a horror-as-metaphor-for-puberty type of thing with a trio of female leads that might fit the bill except that that one actually is shonen. Or maybe seinen. Certainly not shojo at any rate.

(There’s a good piece on Alien Nine by Jason Thompson here: http://www.animenewsnetwork.co.uk/house-of-1000-manga/2011-10-20 if you’re interested).

“I always thought of Ito and Umezu as shonen artists”

They’ve both produced works for various demographics. The Drifting Classroom is certainly shonen.

Can’t think of anything shonen by Ito off the top of my head though – stuff like Gyo and Uzumaki is seinen.

Pingback: MangaBlog — Quick Monday roundup