(Concerning Harvey Kurztman’s EC War Comics)

A Reply to R. Fiore reprinted from The Comics Journal #253 (2003) Blood and Thunder Section. The reply is preceded by scans of Fiore’s response to my initial article. These scans are reproduced with Fiore’s permission.

I will respond to R Fiore’s first few statements by reproducing an edited version of my response from the TCJ message board:

I don’t think my statements in the essay deviate substantially from Fiore’s comments above. I single out a number of stories from MAD #1-20 for praise including a Krigstein story and follow this up by citing three Johnny Craig stories which manage to rise above the dross. However, whatever Bradbury’s own views on the subject matter, I still prefer most of Bradbury’s original prose to the adaptations. As stated in the essay, I do not have much argument against a select few of the early MAD stories being chosen the highest forms of comedy as yet produced in comics. It is the wholesale embrace of the early MAD issues that I’m arguing against

The films and books mentioned in the essay were chosen for easy recognition and their generally accepted levels of quality. I have no difficulty in naming many other modern books of lesser renown (and reputation) which far surpass the Kurtzman war stories in ability and passion: Mo Yan’s Red Sorghum, Jonathan Safran Foer’s Everything is Illuminated, Hikaru Okuizumi’s The Stones Cry Out etc. Further, I will go on record as saying that I find Tardi’s It Was the War of the Trenches superior to the best of the EC war stories.

As Fiore states in his letter, the orthodoxy within the Western comics sphere is that the Kurtzman comics are the best war comics ever made. All these meandering discussions will do not one bit to change this fact. Kurtzman certainly is one of the standards as far as war comics are concerned but he is an unacceptably low standard by which to gauge the genre in my view.

What logic is there in rating the EC War Stories over Palestine or Safe Area Gorazde except some misplaced sympathy for the backward aesthetic and cultural values of comics of a certain vintage? It should not be our concern if the practitioners of a certain period in comics did not have the imaginations or ambition to think beyond the accepted boundaries of their chosen livelihood. There were numerous cultural precedents for superior, honest work on war before that period.

The difference between the majority of the EC War stories and modern war comics is that, in comparison to the great works of war literature (and film), the latter are recognizably possessed of the same purpose and qualities we expect of the finest art. Neither of these works by Sacco may be on equal footing with Catch-22 but both possess that element of artistic ambition and maturity which has characterized many worthy artistic endeavors over the centuries. Kurtzman’s “Big ‘If’” and “Corpse on the Imjin” manage to engage the reader at that level but neither have stood the test of time in terms of their emotional complexity or their meditations on reality and truth.

***

R. Fiore’s letter demonstrates that he is either bereft of comprehension skills or a pathological liar. His willful misrepresentation of his opponent’s views both here as well as on the TCJ message board (placing words in their mouths as it were) indicate a steep decline into critical indolence.

Fiore tries to mislead his readers by suggesting that I am of the opinion that “Kurtzman and the EC artists should not be considered superior cartoonists to Joe Sacco just because they drew comics better.” Nowhere in the article do I even suggest this. Rather my dispute with many of the EC artists is that drawing well (and this is certainly not beyond dispute) is just about all they did with any level of accomplishment. Fiore may be anxious to dump content, narrative and dialogue into a bottomless pit reeking of nostalgia but I certainly am not.

It is telling that Fiore considers my description of the EC war line as children’s comics a form of condescension. In so doing, he totally ignores my statement that immediately follows this labeling in which I state, “I do not say this in a derogatory way, but to set out discussion of these comics within the proper context.” My use of this limitation was, therefore, not meant so much as an insult (though it would certainly be perceived as such by an EC fan who has always considered the EC line as pretty “grown-up”) but as a tool for judging them fairly within an appropriate framework.

Fiore, it would appear, has a latent disregard for children’s books despite his protestations to the contrary. In my view, comics crafted for children and comics crafted for adults must be judged using different criteria. The exact nature of these criteria is not within the scope of this reply, suffice to say that when it comes to children’s literature, a proper account must be taken of their accessibility (both emotionally and intellectually) and limitations. A work that does not meet or work within these criteria must be deemed bad children’s art. A comic prepared for an adult will therefore often fail miserably as art for children. It is precisely within the parameters of children’s literature that a few of Kurtzman’s war stories can be deemed of some merit.

As for my use of the word “juvenile”, readers will find that only once in the essay do I use this word and this is at the beginning of the essay when I am assessing the output of EC as a whole. When I label them “juvenile”, I mean that they were silly and immature. While it may come as a surprise to Fiore, I doubt that looks of stupefaction will greet my suggestion that there exist strange things known as “mature” children’s books. These are books that are considered and fully developed, and which speak to children in ways that are sometimes deemed inappropriate by an overprotective society. This is the reason why I quote Walter Benjamin in my essay as saying, “Children want adults to give them clear, comprehensible, but not childlike books. Least of all do they want what adults think of as childlike…” Benjamin was writing in an era of different “moral” standards but his words retain their significance even in this day and age of ever shifting moral boundaries. The problem is that Kurtzman failed so often even within these parameters, namely what is useful and relevant for the minds of 14 year olds.

In yet another deft act of conjuring, Fiore suggests that I have denied Kurtzman the “title of artist”. This is pure hysterical bluster. The reality is that my criticisms of EC have never centered around Kurtzman’s status as just that but rather the exact quality of the art works he produced. Truly, it is a sorry day when the esteemed critic’s rhetorical skills are coupled with an endless stream of lies.

Fiore’s next deception is to accuse me of failing to articulate that “quality” which is missing from the Kurtzman’s output. Yet even the most slothful reader need only turn to the “War Comics” section of my essay to see that I have provided quite a few details concerning my objections to EC. Fiore, in his geriatrically-imbued arrogance, ignores my points. Within the best of my capabilities, therefore, I will reiterate and expand on what is lacking in Kurtzman’s war stories and why I consider some of these inferior to Tardi’s It Was the War of the Trenches.

In the essay, I provide a short list enumerating the deficiencies which pepper the EC War line. (It is not a definitive listing but it will serve as a skeleton upon which to base further discussion):

(1) Jingosim (“Contact!”; which Kurtzman himself admits was “pretty dreadful stuff”)

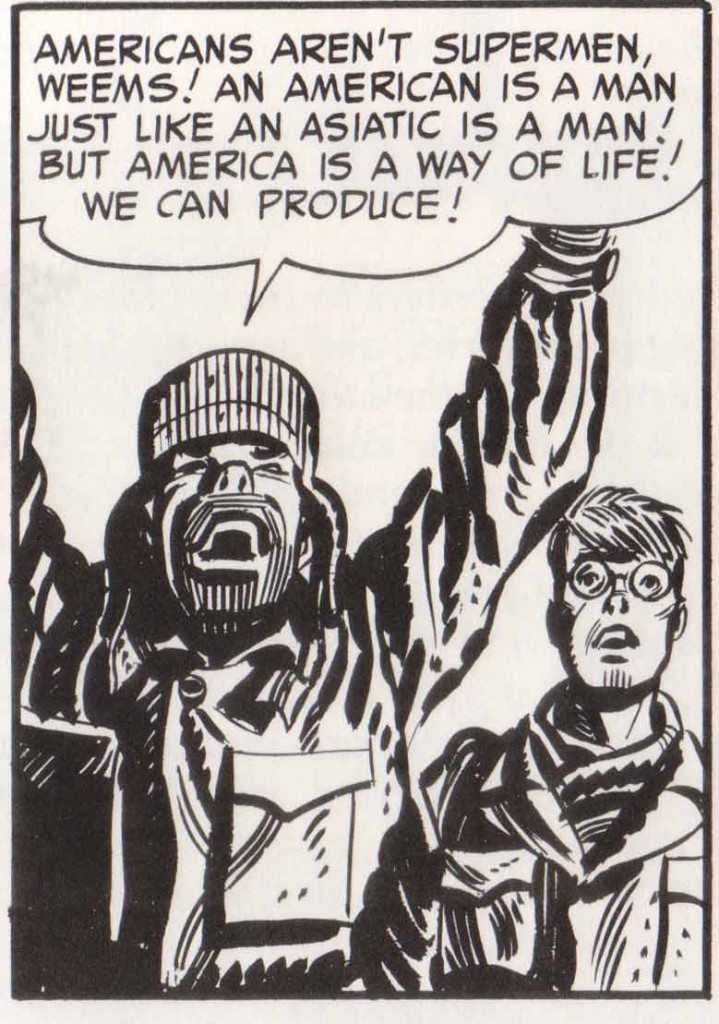

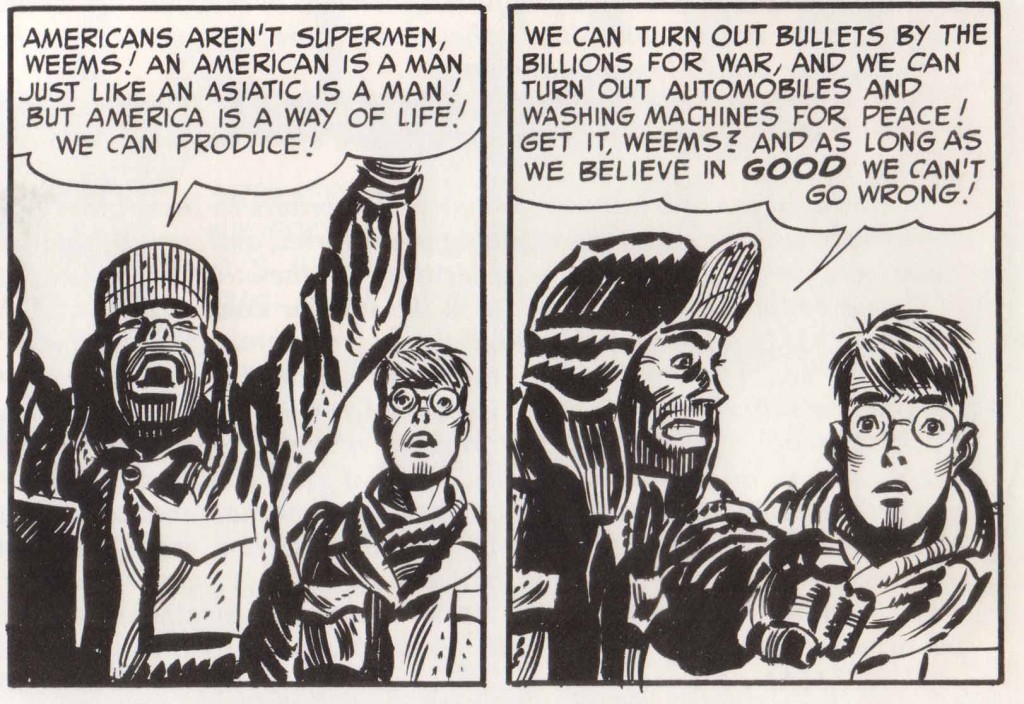

“Contact” is a story about a surprise attack by the Chinese on an American patrol. In the course of the story, we see the American soldiers mowing down the communists with great efficiency after an initial shot by those sneaky communists leaves the lieutenant in charge of the patrol quite dead. Some of this is done with great flair as when the Sergeant opens fire in a darkened tunnel creating momentary lighting effects in otherwise darkened panels. Amidst the chaos, a young soldier who is saved by his superior asks in wide-eyed fashion, “What’s the good sergeant? There are hundreds of them…and there are just two of us!…How can we ever hope to win against so many Chinese? There are ten of them to every one of us!” The sergeant replies, “I’ll show you how we’ll win, Weems! Look up there!” He points up to a T6 observation plane. Cut to a command position where a flight of F-86s and a column of tanks are called in. They proceed to bomb the living daylights out of the enemy. The Chinese are annihilated. Without a trace of irony, Kurtzman has his sergeant exclaim, “Americans aren’t supermen, Weems! An American is a man just like an Asiatic is a man! But America is a way of life! We can produce! We can turn out bullets by the billions for war, and we can turn out automobiles and washing machines for peace! Get it, Weems? As long as we believe in good we can’t go wrong!”

End summary. Now you would think that a story of this flavor would be a prima facie case of pretty abominable propaganda but it would seem that Fiore is quite happy to swallow this kind of bullshit whole.

(2) Dramatic draftsmanship and intelligent structure illustrating inconsequential content (“Thunder Jet”, “F-86 Sabre Jet!”)

Both of these well known stories are beautifully illustrated with planes delineated in clean and precise Toth-ian geometric minimalism. “Thunder Jet” purports to provide the reader with a ride along with the pilot of a Thunder Jet through ‘Mig Alley’. It seeks to communicate the concerns of said pilot with regards a perceived technological and skill gap. In the story, the Thunder Jet patrol spots an enemy train convoy and bombs and disables it. They meet some Chinese Migs, beat the shit out of them because they’re “being flown by kids…no formation, no nothing! They come up, every day, like a class room!” The patrol returns to base and you (the pilot, as the story is partly told in the first person) emerge from the plane as the narrator solemnly declares, “And as you finger the torn aluminum, you think of the 20mm cannon the Migs have! And then you think how the Migs go faster than you, and you think how the Migs outnumber you. And you think of that classroom in the sky! And then you think…We’d better do something, soon…pretty gol-darned soon!”

While this story displays a high level of achievement artistically, its narration flounders in insipid hard-boiled mannerisms which would not look out of place in a modern day superhero book. The story is devoid of any recognizable human emotions be they fear, remorse or courage. Maybe there’s a whiff of arrogance but not much else. Nothing beyond a plain stating of the facts—in other words, it’s a technical manual empty of human interest. If the work is assessed as a tale of adventure, the reader will search in vain for evidence of heroism or any trace of visceral excitement. It is a pleasure to look at and that is all.

(3) Exquisitely dignified corpses (“The Caves!” from the Iwo Jima issue)

“The Caves” is an interesting story because its intent may seem fair minded and noble. The story starts with some portentous dialogue: “…and amongst the boulders and ravines, lay the sinister constructions formed by the hand of man…The Caves!”. The story concerns a Japanese foot solider who entertains treasonous thoughts about betraying his emperor. In essence, his crime is that of planning to stay alive while others choose death over the dishonor of surrender. Among other things, the story attempts to relate the not unheard of conflict between Japanese foot soldiers and the high minded ideals derived from bushido demonstrated by the officer class. It ends in a sort of positive light when the Japanese foot solider is demonstrated to have regained some of his honor within his own fixed parameters of reference (he kills himself in a Kamikaze-style charge).

In this story, Kurtzman shows some willingness to extend a degree of humanity to the enemy, something he was a tad more reluctant to do in the case of the danger posed by North Koreans and Chinese in the more contemporary Korean War. The difference is the distance provided by the passage of a few years.

With all these factors going for it, one might honestly ask why this story remains so utterly unconvincing. Why does the reader remain thoroughly unmoved by the condition of the Japanese protagonist? For one, there is no context for his betrayal of his culture’s values. We are not made to understand or perceive the awe with which Japanese infantry men often looked upon their officers or the reasons for their almost unquestioning obedience. The Japanese officer might just as well be an insane Allied officer as far as the story is concerned. We don’t understand the depth of his betrayal or cowardice and we therefore do not care for his predicament. Empty of both emotional connection and cultural information, it reads like a trite narration of a war time snippet. Kurtzman had no understanding of the Japanese he was portraying and failed in this nobly intentioned depiction of the enemy.

While “The Caves!” fails quite completely in its understanding of the “enemy”, I also chose this story because of its conspicuous falsity in pictorial representation. I’m not only talking about the failure in mere technical details like the overly enclosed space of the cave which makes the infantry man’s survival of several grenade blasts next to impossible but also the failure to represent the true horror of men throwing themselves into the arms of the enemy and hence death, and the truly awful consequences of a close quarters grenade blast. These shortcomings have a direct bearing on the effectiveness of the story. With death made so eminently easy on the eyes, there seems no reason for the infantry man’s cowardice. Where is the courage inherent in such a sacrifice? Why the vacillation? If we do not feel his dread, we do not journey with him through his resultant emotional turmoil.

(4) The poverty of the enemies’ beliefs and the failure of their resolve (“Dying City!”)

(5) Sanctimonious depictions of the plight of good, honest, salt of the earth Koreans (Southern presumably; in “Rubble!”)

For reasons of space, I will allow interested readers the pleasure of exploring the catalogue of half and one-sided “truths” depicted in the above two stories.

(6) Retribution for cowards (“Bouncing Bertha”), traitors (“Prisoner of War!”) and grinning, nefarious enemies (“Air Burst”).

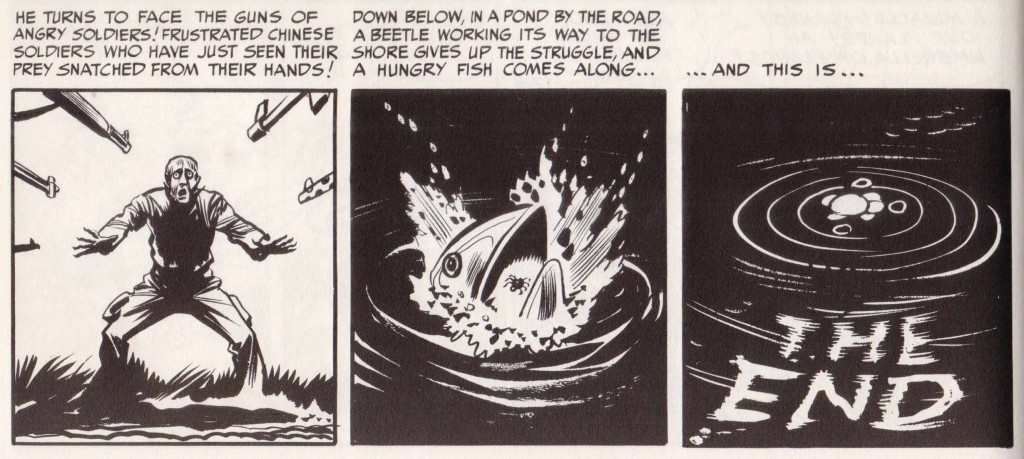

In the opening sequence of “Bouncing Bertha”, a bug struggling on the surface of a pond is compared with man — “…and yet, that little bug has enough sense to keep struggling…to keep fighting and to have hope till the very end. Even though he doesn’t know how he’ll save himself! It’s just like people!”. In the story proper, a tank crew meets with an accident, are deprived of their tank and find themselves behind enemy lines during the Korean War. While most of them decide to stand and fight, one of their number, PFC Allen, deserts and decides to surrender to the enemy. The heroic crew is finally saved by an air strike and an airlift via helicopter while the craven coward (and he is certainly drawn, somewhat predictably, with villainous, slovenly features) is left to the mercy of the angry Chinese.

What we have here is a crude extension of the black and white values propagated by the EC Horror, Crime, and SF titles where every villain gets their just desserts and where noble acts are rewarded. Fiore says that I have somehow misread Kurtzman’s purpose here. He suggests that I have inserted the false theme of cowardice where the story’s actual focus is that of the concept of “struggle”. But Fiore’s faculties are blinded by his passion for Kurtzman. His idol’s deployment of the word “struggle” is inextricably linked with the concepts of loyalty and courage. Fiore wants us to believe that Kurtzman was focusing on something amoral and existential but the denouement of the story suggests otherwise. Kurtzman is really only interested in a particular form of struggle—the “good” type—one which is plainly linked with faithfulness and bravery.

If Kurtzman had meant only to illuminate the concept of man’s “struggle”, he would have chosen a dramatic situation which was less clearly black and white. Instead of muddying the waters, he would have chosen to have the traitorous Allen survive rather than his more loyal comrades. For Allen also “struggles” in his own way, he clearly wants to live and will do anything to survive his situation. He chooses the rather risky avenue of surrendering to a somewhat unpredictable enemy and is willing to buck the trend of stalwart courage demanded by society. His death can only be seen as the result of a lack of bravery. Allen only fails to “struggle” for his country and his fellow soldiers. His crime—a deplorable brand of cowardice in the eyes of his fellow soldiers.

In “Prisoner of War!”, a group of American soldiers is taken captive by the North Koreans. The not too subtly named Benedict—who is seen to have a vile, insane look on page 2 of the story—cozies up with his North Korean guard and even helps him track down his comrades when three of the prisoners try to escape. The three, however, do manage to evade capture and, while recuperating behind their own lines, hear a retrospective account of how Benedict is killed by his North Korean captor during a summary execution of American prisoners.

Yet again, this story represents a return to the retribution ethos of the horror, science and crime titles. On this occasion, it is partially “softened” by the fact that the rest of Benedict’s non-traitorous comrades also die in the same ignominious way. The traitor’s end is, however, more focused and wretched because he is killed by the very person he was sucking up to. He gets his just desserts for being a turncoat (it never pays to be a turncoat in EC-land). Like many of the other EC stories, this is a conception of humanity and reality that would not look out of place in a Silver Age superhero comic.

“Prisoner of War!” is also firmly locked in a 50s time warp both politically and culturally. The communists, as in many of the other EC stories, are seen only as inhuman beasts; distorted and corrupted in the best tradition of political propaganda. While it is undoubtedly true that the North Koreans were guilty of committing numerous acts of democide, we of course hear nothing of the equally wonderful massacres by the squeaky clean South Koreans and American GIs. Clearly such insights and journalistic integrity were beyond Kurtzman (and many others of that time) but this propensity to swallow the party ethos hook, line and sinker must suggest that the work is bereft of the insights which are the hallmark of the best literature. The story’s usefulness as a historical document extends not so much to its portrayal of the realities and complexities of the Korean War but the prejudices surrounding it. The modern day reader is often swayed by the more realistic setting and the less fantastic turn of events in the Kurtzman war stories but the underlying falsity is clearly in evidence.

“Air Burst” (Frontline Combat #4) concerns two Chinese mortar squad soldiers who find themselves alone after the rest of their squad is decimated by American air bursts. One of them, Lee, decides to set an explosive-tipped trip wire to kill any Americans who happen to follow their line of retreat. The two Chinese soldiers continue to use their sole mortar to assail the Americans but finally meet their match in a strafing fighter plane. Lee is injured but his comrade, Big Feet, manages to escape unscathed. Big Feet attempts to carry Lee to safety but then encounters a flight of American bombers which drop “surrender papers” on their position. Big Feet decides that they should surrender and retraces his step to surrender to the Americans. He forgets about the tripwire explosive device and kills them both in the process.

There are a number of ways to view this story. Those of a charitable disposition would suggest that this is a balanced depiction of the communist Chinese. Big Feet is depicted in a reasonably objective fashion. He tries to save Lee because of the bonds of friendship and, in his own simple way, realizes that the Americans offer hope and safety. He is defeated only by the calculating, malevolent Lee who is the cause of their misfortune (he is the one who sets the trap to kill the Americans).

Someone of a more critical disposition would suggest that this is unadulterated American war office hoopla. The story draws broad caricatures of the Chinese communists. On the one hand, there are the simple-minded natives who have been caught up in a war which they don’t really want to fight and, on the other hand, there are the nasty communists who are a danger to both us (the Americans) and themselves. Filled with the dividend of self-righteousness emanating from the conflict during World War 2, the story ends with the approach of the Americans whose generosity and mercy even extend to those horrible communists.

If Kurtzman’s purpose was to narrow the “humanity gap” between the American and Chinese soldiers, he can only be accounted to have failed miserably in “Air Burst”. An enemy who is seen to contemplate the death of a fellow American with pleasure would not have met with approval among his readership nor would it have reduced their inherent prejudices. There is a marked difference in the portrayal of the enemy here and that of Rommel (the “good” enemy) in “Desert Fox!”.

***

To end, I will look at the two stories which have come to represent the peak of Kurtzman’s war oeuvre.

“Big ‘If’” (Frontline Combat #5) is a story which relates, in flashbacks, the untimely end of an American GI (called Maynard) from a shrapnel wound. The formal and structural elements of the story have been cited most often for praise. Kurtzman makes liberal use of a three panel staggered close-up, a technique that is also used with great regularity throughout the war stories. The wooden devil posts which bookend the story provide a sense of impending doom as they fill the background in the small panels on the penultimate page of the story. The sound of a descending shell substitutes for the absent laughter of the same. On the final page of the story, the soldier’s face is wracked with agony in contrast to the grinning devil posts on the opposing page. The reader’s expectations are tautly held by the snaking narrative, the tension slowly building to a climax in which the reader’s barely held suspicions are made flesh in the form of a bleeding shrapnel wound

As an example of deft narrative technique, “Big ‘If’” remains an interesting case study. Yet it fails to match this achievements in terms of its emotional impact. “Big ‘If’” strives to delineate the fragility of life by throwing light on the fine threads of possibilities upon which life hangs. The protagonist is a man beset by unfathomable forces. It is an existential tale which could be transposed to a non-military setting without much difficulty (it has thematic similarities with Eisner’s “Ten Minutes”—from The Spirit Section Sept 11 1949— for example). Yet we do not feel for him because he is an enigma shackled by leaden narration, a disconnected collection of lines bemoaning his fate. There is little in his characterization which suggests that he is a fleshy human, nothing in his words to allow us to empathize with him. Each twist in Maynard’s destiny is rushed as a result of constraints of length thus diluting our sympathy with his final end. The choices he makes are insufficiently jarring or nuanced, his despair without context or meaning for the reader. In “Big ‘If’”, Kurtzman allows us to view the death of a soldier away from the dehumanizing aspects of mechanized warfare. It is one of his most valiant attempts at concentrating and humanizing mass conflict, but he falls short by a few degrees despite or, perhaps, partly because of his elaborate forms of artifice.

“Corpse on the Imjin!” (Two Fisted Tales #25) is one of Kurtzman’s most powerful war stories. There are few pages in the EC war comics as powerfully drawn and composed as the final two in this tale: the violent movement of the American solider as he drowns his enemy are given force by the use of the words “dunk…dunk…dunk” in the narration as well as the desperately clawing hands of his opponent. The intensity and concentration of the reader is brought to bear on the act of murder by the staggered close-up of the man’s last drowning breaths and then the gradual movement away from the floating corpse who remains, to the end, without name or origin. The entire incident is driven solely by bestial instincts and the final detached corpse as objectified as the inanimate cases and tubes which are seen floating down the Imjin at the start of the story. Artistically, “Corpse on the Imjin!” is short, sharp, and brutal and this is exactly what is required to communicate the act of killing both in war and in self-defense.

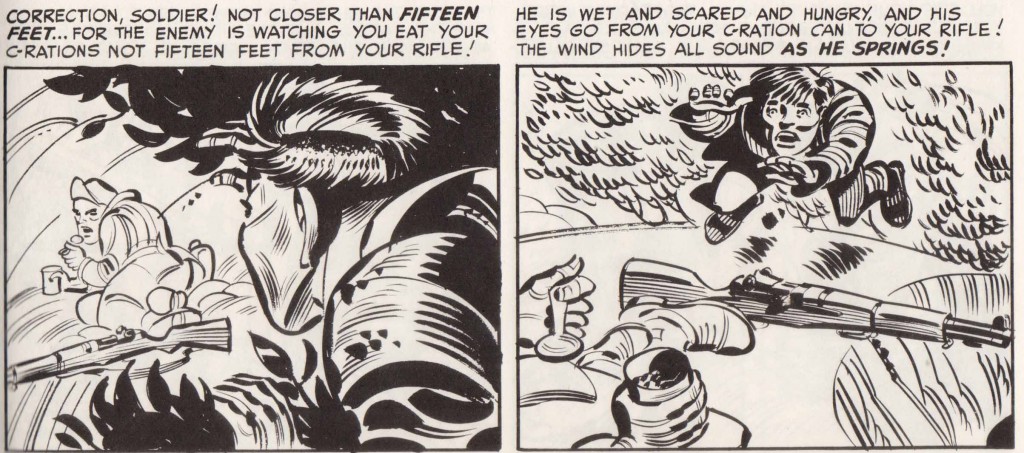

There is, however, a familiar dark cloud which sullies the experience. It is one that overwhelms almost all the EC line—the clumsy, redundant narrative. The fight scene on pages 3 and 4 is filled with burdensome text and there’s even more scattered throughout the story. Kurtzman (as in many of his other stories) felt a need to shove his point in his readers’ faces. Subtlety is at a premium. On page 2 of his story, he has his American soldier drive home his “moral” when he shows him thinking to himself, “Now with all the long range weapons, we can kill pretty good by remote control! And we never get closer’n a mile to the enemy!” This is naturally followed by close hand to hand combat with a communist soldier. Not satisfied with merely showing the enemy at close quarters peering over the American, Kurtzman finds himself locked into the narrative conventions of the time as he intones, “Correction, Soldier! Not closer than fifteen feet…for the enemy is watching you eat your C-rations not fifteen feet from your rifle”. On the final page of the story, rather than let us experience the full force of his artwork, he force-feeds us some insipid platitudes: “Have pity! Have pity for a dead man! For he is now not rich or poor, right or wrong, bad or good! Don’t hate him! Have pity…For he has lost that most precious possession that we all treasure above everything…he has lost his life!”

Kurtzman apologists and fans have been willing to forgive the avalanche of ham-fisted writing which marks most of the EC war line (this being but one example amongst many) but I certainly am not. They want to sweep these sins under the carpet, as if words are somehow irrelevant to the cartoonist’s art. When called into account, they plead historical context as if good writing was only invented during the late twentieth century.

In his letter, Fiore states that “unless you’re giving him extra credit for antiwar sentiment I don’t see that “War of the Trenches” is any better than the best of Kurtzman”. Frankly, I find it astonishing that Fiore is so enamored of Kurtzman’s comics that he will even stoop to making such a statement. Fiore has clearly suckled so long at the teat of “comicness” (the essentialist view of comics which seems to be the basis of all his criticism) that his taste buds have atrophied. His unwavering view that comics are “a crap form contaminated by art” has led to his wholesale acceptance of aging works of only modest aesthetic merit. This can be the only explanation for his blindness to the superior qualities in Tardi’s war stories and his desire to persist in wallowing in his sty of EC mediocrity (don’t forget, this is the man who once wrote, “Any discussion of EC has to begin with the horror comics, not only because they were the most infamous and popular, but because they may have been the best.” This before proceeding to wax lyrical on the aesthetic rewards to be derived from the EC hosts (The Comics Journal #60).

An argument for Tardi’s work over Kurtzman’s would fill another essay. Tardi’s work is richer in characterization as well as moral and psychological subtlety. It is possessed of an aesthetic congruity and consistency between the words and images that is largely absent from even the best of Kurtzman. Further, the war is more perceptively individualized than anything found in the EC war comics creating a greater degree of empathetic truth. The violence is exact, cruel and never an excuse for heroics. The overall artistic vision and undivided purpose of It was the War of the Trenches makes it superior to just about anything in the EC war line.

***

In his letter, Fiore writes, “what gives them [the war comics] their special quality is how he determined to do it. Kurtzman’s theory was that reality was far more interesting than the absurd fantasies war comics had engaged in up to then.” Fiore seems to be of the opinion that Kurtzman’s war comics represent some sort of unshakable benchmark in realism. This is a delusion. I have already enumerated a few of the fantasies that persist within the EC war stories. At best, most of them can be seen as ironic adventure tales to be read at bedtime under sheets with a torchlight. They almost never allow us to acknowledge any revulsion for the abomination that war has always been.

Not once does Fiore counter my claim that the overall weight of the stories in the EC war comics fall drastically short of the mark. Instead Fiore presents us with a few examples of Kurtzman’s realism in his letter thinking to deceive readers too lazy to peruse the comics for themselves. Yet even this very selective list—culled from the first few issues of Frontline Combat—presents a majority of stories that do not sustain any level of realism. Let’s take a look at what Fiore offers up in Kurtzman’s defence [for reasons of space, I will only consider a few of them]:

“As a platoon retreats in the face of the Chinese counterattack during the Korean War, they are pinned down on their way down a hill, and call in the Air Force to burn the enemy out with napalm. “

The summary concerns “Marines Retreat!” from Frontline Combat #1. The napalm attack is seen as a small explosion and the resultant carnage no more than a few innocuously drawn charred limbs gathered in a small corner of the third panel on page 5. If this is the reality and horror of a napalm attack, it is a wonder there’s such an outcry against its use. The napalm attack is followed by two pages of action which would not look out of a place in a boy’s adventure comic (yes, I know, that’s what the EC War line actually was) and a final brave stand by one of the wounded who in good old war comics tradition wants to cover for his comrades since he’s “finished”. If this is “realism”, we should all be so bold as to spit in its face.

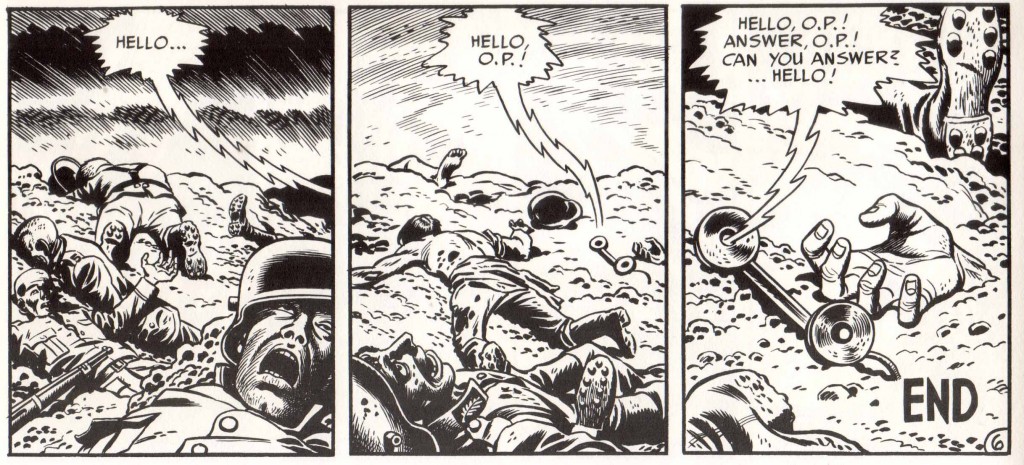

“The loan survivor of an artillery barrage on an observation post must call in another artillery barrage on his own position when it is overrun by the enemy.”

The scenario is drawn from “O.P. !”, (Frontline Combat #1) and tells the story of how a soldier assigned to an observation post sacrifices himself in the line of duty in order to hold off the Germans who have infiltrated his trench. In other words, it is one of a number of traditional brave, self-sacrificing soldier stories that pepper the EC war comics.

Still, this is one of the few EC war stories where the dead (who somehow still remain wholly intact after being pummeled by artillery shells) are seen to lie in something resembling an undignified position (the protagonist and hero—that’s clearly what he is—is buried underground at the end of the story). The EC artists may have paid close attention to the number of rivets on a machine gun but they almost always took a step back when it came to the reality of death and suffering on the battlefield. As a result, dispatching the enemy (and the whole concept of warfare) resembles something clean and efficiently humane, not something appalling and despicable to be resorted to as a last resort.

Another example Fiore cites is “Zero Hour” (which is also set in World War I) in which “a wounded soldier is caught on the barbed wire. The enemy allows him to stay there in order to demoralize his comrades and draw them out to be shot when they try to rescue him. After he has groaned piteously for hours, and three soldiers have been killed trying to rescue him, his own officer shoots him to put him out of his misery.”

In the Cochran reprints of Frontline Combat, Kurtzman is made to discuss the genesis of “Zero Hour”. In the interview, Kurtzman says he saw the scene in All Quiet on the Western Front and that it also appeared in “several war movies.” As with the Feldstein-Bradbury stories in the EC Science Fiction comics, Kurtzman is on firmer ground when he follows the example provided by his artistic predecessors. This makes “Zero Hour” one of the more “realistic” stories in the EC war line.

Since the scene in question does not appear in Remarque’s book, one assumes that Kurtzman is talking about Lewis Milestone’s adaptation. Returning to the source material, what we find in Remarque’s book is this: men scrabbling for food and luxuries, pages of just waiting, a feeling of sickness and loathing at the endless descriptions of amputations, decapitations and festering injuries which finally create a feeling of neurasthenia on the part of the reader. All told without hyperbole in an unsentimental, plain narrative voice.

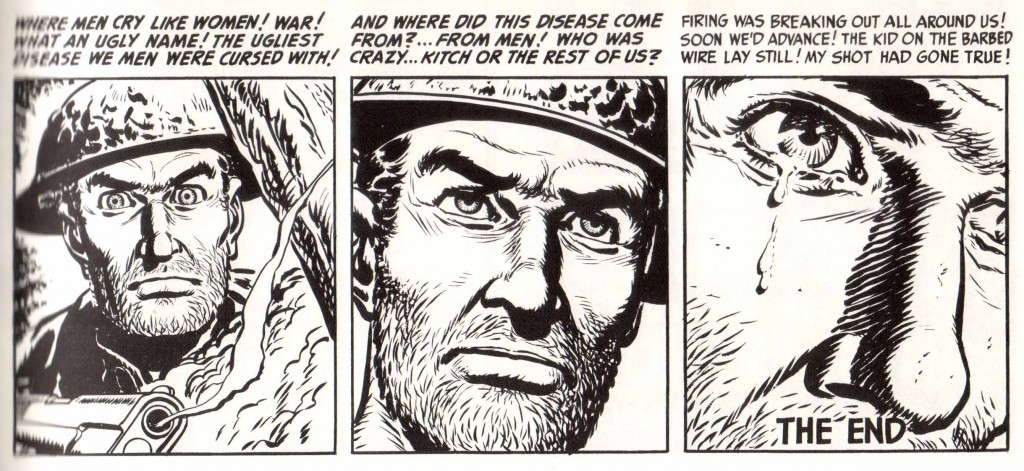

What we get from “Zero Hour” in contrast are some maudlin images of a soldier’s anguish. In the final three panels of “Zero Hour”, we get a gradual close-up of the sergeant before three tear drops mark this hard-as-nails soldier’s face. This is capped off by some truly idiotic narration: “War! What an ugly name! The ugliest disease we men were cursed with! And where did this disease come from?…from men!” If there is any truthful emotion or realism within this story, it is completely obliterated by Kurtzman’s heavy-handedness. If a work of art fails to elicit reflection on its presumed theme because of its narrative ineptness, one can only say that it has also failed a crucial test pertaining to its absolute quality. The resultant sappy entertainment has nothing to do with realism.

“Tales of the gallantry and dash of General Erwin Rommel are juxtaposed with scenes of Nazi atrocities, including scenes from the concentration camps, which Tong claims Kurtzman ignores.”

Fiore once again demonstrates what a poor reader he is with this statement. Frankly, it’s almost getting a bit undignified. Nowhere in my essay do I even suggest that Kurtzman ignores the Holocaust. In only one instance do I bring up the concentration camps (in particular Buchenwald) and in that instance it is only to illustrate the point that young readers are quite capable of assimilating such atrocities (whatever their more protective parents might think). “Desert Fox!” (Frontline Combat #3) demonstrates that Kurtzman was not totally at odds with this point of view and would occasionally overcome his squeamishness with regards violence to show true scenes of horror (“true” violence being reserved only for the pages of the horror comics). The page (drawn by Wally Wood) stands out because it is at odds with just about every other depiction of violence in the EC war lines. Fiore deceives his readers when he suggests that this page is somehow representative of the rest of the war comics. Further, this point does not even take into account the fact that the page is clearly meant to balance out (and deflect criticism) of the honorable depiction of Rommel in the story. The war atrocities are a side dish. It’s just one example of the kind of spineless artistic schizophrenia that inhabits many of the EC war comics.

“A submarine captain is stranded when his ship has to make an emergency dive. He is about to be rescued by an enemy destroyer, but is left to drown because his submarine surfaces to attack and the destroyer must sail away to evade it. “

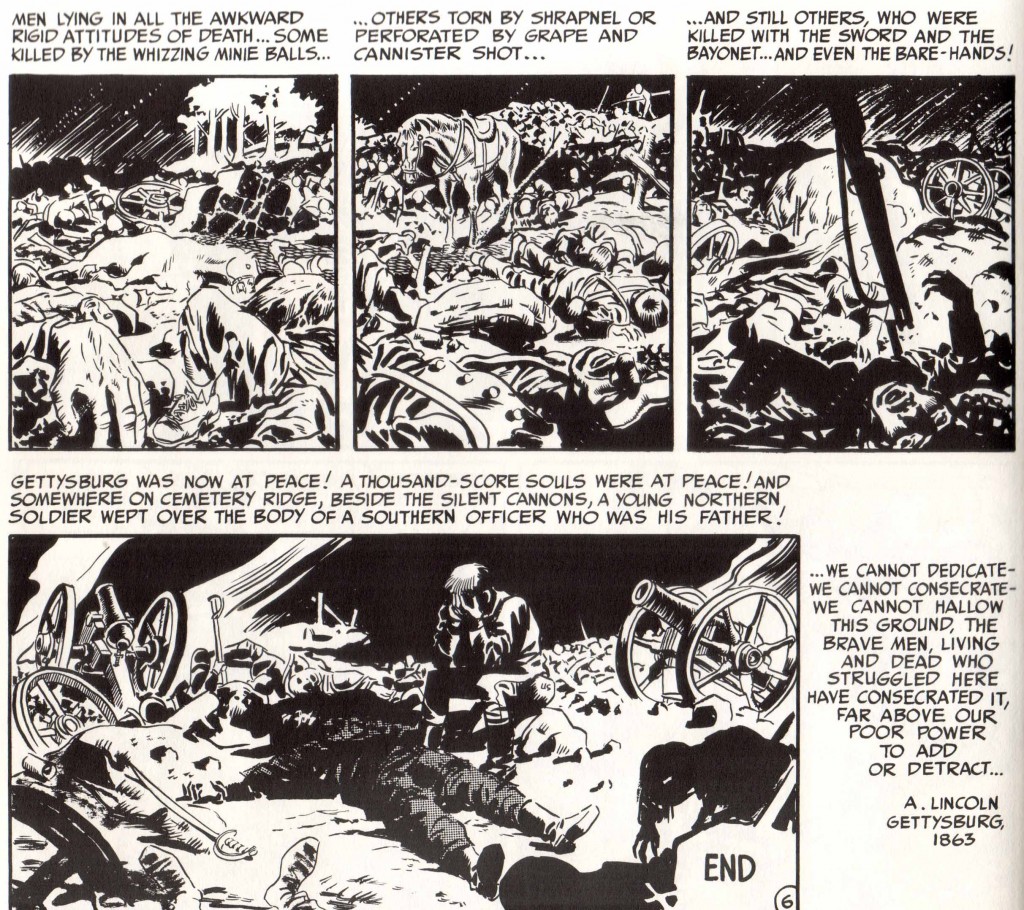

“A Union soldier at Gettysburg discovers that the Confederate officer he’s killed is his own father.”

“A French civilian notes the drab uniforms of the Allied soldier, and recalls how he and his fellow officers from the Academy insisted on wearing their colorful traditional uniforms in World War I and were slaughtered for their vanity. “

In my article, I suggest that the EC war stories are “gentle, dignified and bloodlessly pleasant” and that “they glorify by exclusion and by failing to relate life’s simple truths.” It is quite obvious from the few examples he chooses that Fiore believes he can counter my statements by demonstrating that Kurtzman’s war stories contain images of people killing each other and dying, as if this wasn’t an element in just about every modern day action movie.

To strengthen this somewhat defective point, Fiore points us towards two tales that once again demonstrate the EC writers’ deft hand at irony and the “shock” ending.

Both “Unterseeboot 133” (Frontline Combat #1) and “Gettysburg!” (Frontline Combat #2) care little for the realities of war. There are exciting explosions and people are knifed and killed. In short, they are mildly disguised adventure tales (masked with “historical authenticity”) striving to titillate their young audiences. “Gettysburg” in particular is a story obsessed with getting to its final twist ending. The war is merely a backdrop and an excuse for the denouement. A person glances at the dead bodies piled up on the final page of the story and hardly even registers them. They’re insignificant, just ink blots on paper without a trace of emotional meaning.

Fiore does Kurtzman a disservice when he suggests that “pacifism was not an option” during that period in the 40-50s. An artistic philosophy which dictates that the atrocities of war should be presented with unadorned, unmasked truth does not equate with pacifism. Further, he does not make a good case for his artistic hero when he writes, “Kurtzman’s sensibility is shaped by World War II, and assumes that in a world that breeds Hitlers pacifism is not an option.” I wonder if this is an inadvertent or reluctant unveiling of Kurtzman’s limitations. How are we to fully respect the works of a war artist whose vision does not extend beyond his immediate social circumstances and pressures?

The barely concealed secret about war is not that people die and that people kill each other but that they do so in ways which are thoroughly repellent. Most of the EC war stories on the other hand present themselves as mere candy floss. Further, there is almost never any adequate depiction of suffering within the EC war line which is strange considering that war is violence directed towards just that end. When you read books like All Quiet on the Western Front or, to take a more recent and less elevated modern example, Philip Gourevitch’s We wish to inform you that tomorrow we will be killed with our families (which concerns the Rwandan genocide), the overwhelming feelings are quite simply those of nausea, revulsion, and a very deep anger. We are left in no doubt whatsoever that war is horrible and not an insignificant backdrop to some contrived twist of fate.

If Fiore cannot differentiate between mere portrayals of violence and truthful, cohesive depictions of the same then that is his good fortune. He can fill himself with the masses of similarly half-hearted (if not thoroughly insipid) depictions of the “realities” of warfare which fill the book shelves and cinemas. I would suggest, however, that readers take note of this deficiency when he presumes to promulgate his inadequate standards to all and sundry.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

I can’t really agree with you about the Kurtzman war books, Suat….I admire some stories in them greatly, and while it may not be saying much, it is hard to deny that they (and the best stories in Warren’s Blazing Combat) are certainly far superior to the war glamorization seen in all other war comic books, including all of the supposedly anti-war Kubert-edited DC books.

And I notice that though you cited it, you avoided discussing “F-86 Sabre Jet”, the better of the stories that Toth drew for Kurtzman.

Fiore’s North American centric views are to be expected. The best comics war stories ever written were written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld (drawn by Hugo Pratt, Alberto Breccia, Solano López and a few others – one of my favorite stories was drawn by Jesús Balbi, for instance).

I wish I could read the books Domingos mentions yet one more time. Anyway, in general, I don’t dispute your assessment, Suat. I have no great love for Mad and its influence of schtick, on the underground or wherever. And many of the ECs were hideously overwritten. But you overshoot the target—the few best works are what make the rule, that make EC deserve its reputation: those little Woody moments like There Will Come Soft Rains, a few of the Kurtzman war stories, Krigstein’s experiments (and his spirit was crushed that he couldn’t do more). Also, as you say, it should be remembered that this stuff (and most of the comics of the last century) was done for kids. That fact makes it multiply pathetic that so few of the comics contemporary with EC and since, well into the present century are even as good as what was done at EC. It isn’t the medium at fault, but the practitioners. The mainstream is largely an embarrassment, and for the rest of us, our sights are set far too low.

Domingos wrote: “The best comics war stories ever written were written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld.”

Because he was a radical leftist propagandist of course.

I mean, didn’t Oesterheld portray Ché as a hero, when, in fact, Ché was little more than Castro’s chief thug and enforcer?

How is that somehow “more accurate” or better than Kurtzman’s stuff?

When I first read about the “Anniversary of Hate” I groaned. I braced myself for more deeply tired and overwrought spleen-venting rants about superheroes. Imagine my surprise when one of the earliest articles was an attack on Chris Ware of all people! I’m a fan of the genre in general, but I don’t mind attacks or critiques on it, especially such deserving targets as Geoff Johns, hell I engage in such things myself. Noah, you’re doing a great job keeping things evenhanded and spreading the hate all around.

By the way, the whining of this site’s huddled masses over someone daring to have a different viewpoint of a critical darling is deliciously hilarious and absurd.

Now I have to engage in some Hate myself. Domingos, while I agree that in general American comics fans are ignorant of the glories of European comics and championing them is quite laudable ,and I have discovered superb comics to read or at least look at despite all the hot air. I do appreciate that. However, your shrillness is making me want to throw all my Bilal, Moebius, Trondheim and Druillet in the trash. We get it, American comics all blow. Is your goal to become a caricature that can be counted on to predictably chime in on any topic about how Hugo Pratt is just better? Also your Eurocentricity, beyond being just obnoxious displays an sickening ignorance about world comics. What about great military manga like Cat Shit One? I guess they don’t count because they weren’t published in Pilote.

MG, I think Domingos’ favorite comics artist (and one of the few he would actually call an artist) is Tsuge.

Oh, and thank you! Glad you’re enjoying the roundtable.

Russ: Che isn’t very good. Oesterheld radicalized is views during the 70s. Unfortunately for him economical pressures made him write more and more for Columba, a commercial venture is ever there was one… Che and other left wing, not so good, things were published by small publishing houses. The comics I meant above were written during the late 50s, early 60s. I talk about one of them, here.

MG: I’ve thrown “all my Bilal, Moebius, Trondheim and Druillet in the trash” ages ago. You know nothing about my taste if you think that I like such slick bundles of nothing at all.

All the Oesterheld stories I talk about above were published in Argentina.

As for Cat Shit One thanks for the tip.

Domingos — Thanks for the clarification.

I understand, given Oesterheld’s leftist politics and the fact that he and Che were fellow Argentinians, why he would find it difficult to not lionize Che and paint him as some larger-than-life hero.

I’ll concede that Osterheld’s other material may be different, unfortunately, it’s not easy to come by where I come from.

Are there any translated anthologies of his war material out there that you know of?

Domingos’ comics canon is here.

Yup, it’s in various languages (Greek, even!), but no English.

Suat, this is a totally enjoyable takedown of R. Fiore.. (and of the EC war comics, too…but I enjoy the personal shots more).

Domingos — No Tintin? No Asterix? Interesting.

I’m curious what you think of “Amazing Spider-Man” #33. I find that story moving even today. The pacing and imagery — particularly the drama during the sequence where Spider-Man is pinned under the huge piece of machinery — is some of the best I recall seeing anywhere in any comics genre. I think that because Lee and Ditko were no longer on speaking terms when Ditko plotted and drew that story, Ditko did something extraordinary with the visuals, and created a powerful chain of sequential art that has never really been duplicated.

That’s my opinion, anyway.

If Domingos likes that, Russ, I’ll print out your comment and eat it.

I can’t understand this kind of criticism, not to mention it’s completely ahistorical. EC Comics were conceived as comics for young people. It’s what they were. Entertainment for young people. That is the history of the vast majority of comic book. So, within the comic book, it’s not unreasonable to say they were the best of war comics (although arguably of course, but not unreasonable).

I mean, why compare something that was conceived at the time (1950s) as entertainment for young people (kids of the 1950s, remember) with Apocalypse Now, which was not designed for “kids” neither as ‘entertainment’ (the 1970s New Hollywood) ?

(not denigrate the entertainment –even as art; there is much art in history conceived as entertainment, and now I’m not talking about comics).

Even more, why compare EC war comics with Tardi’s It Was the War of the trenches, a work made for another market/audience, another historical moment (1980s), with other publishing formats (which didn’t exist in the 1950s comic book industry and were not even conceivable at the time, nor Kurtzman would have allowed to use them) and, above all, a work designed for a different type of audience, adult audience? With Tardi already exists something called Bd adulte (Bd adulte driven by many European authors who, incidentally, were greatly influenced by Kurtzman and Kurtzman’s MAD, besides underground comix).

So, comparing Tardi with EC war comics seems absurd to me. And of course, ahistorical. Not to mention Jonathan Safran Foer. I can understand the comparison Foer-Tardi, but with EC comics?

Pepo, I’m not sure I follow your reasoning. Are you saying it’s never okay to compare works across time periods or cultures? Surely that can’t be right; I mean, one of the way people — artists, critics, everyone — thinks about art is by comparing and thinking about how different works compare or contrast with each other.

In any case, Suat is *reacting to* a critical consensus that *compares EC comics to other comics* and makes great claims for them. Suat isn’t saying that EC comics have no worth. He’s saying that the claims made for them — that they are among the great achievements of comics — is not convincing. He does that in part by comparing them to other things that he considers to be more substantial achievements.

I mean, do you or don’t you agree that EC comics are a great achievement? Or are you really saying that it’s unfair to evaluate EC at all because it’s of its historical moment and therefore cannot be compared to anything ever? And if it’s such an isolated, unreproducible phenomena, how is it possible that anyone would want to look at it, since it apparently has nothing to say to us outside of its own time?

Leave aside the historical issue, although I think in the case of comics, and comic books, I think is very important.

Would you compare, say, Sargent Fury with Capitaine Conan?

In other words, would you compare Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley with Enid Blyton’s The Famous Five? Really? And for what?

Noah — Why? Because it’s a superhero comic?

What difference does that make? And I say that in earnest….

I’m not familiar with any of those…but I think you’re rather missing the point. Suat has a very clear reason to make the comparison he’s making. That reason is that EC Comics are often cited as one of the great achievements in comics.

Also…it’s often useful or interesting to compare disparate works. You can highlight differences and find unexpected similarities. Suat fleshes out what’s good about Tardi, for example, by thinking about it in relation to EC. Compare and contrast is a really basic critical move. I find the resistance to it in comics circles bizarre.

Whoops…that last was to Pepo.

Noah — Yeah, well, I think he’s being unduly harsh on the EC stuff. They have their weaknesses, and they do suffer at times because of the production-line process inherent in comics back then. But the fact of the matter is, it’s pretty clear that the creators poured their hearts and souls into those books, and made advances that significantly raised the bar on comics.

Just because the bar may be higher now to some degree does not automatically mean everything old is crap.

I’m a big science and technology buff, and just because the iPhone is light years more advanced than, say, Nikoli Tesla’s AC induction motor, does not lessen one iota Tesla’s amazing work.

Have I ever mentioned that sometimes I think you guys are elitist doody-heads?

As I usually say: if I’ve chosen comics to be an elitist, I’m a poor elitist indeed.

Besides, if an elitist is someone who likes great art I’m your guy…

Re. Spidey, I’ll check it out.

Pepo: how about comparing Kurtzman’s children’s 50s war comics with Oesterheld’s children’s 50s war comics? Is that OK?

Domingos — I’m a sucker for great art as well.

Regarding “Amazing Spider-Man” #33 (along with the latter part of #32), it’s one of only a handful of superhero comics I read as an adult that has ever evoked a strong emotional response similar to that triggered by portions of an exceptional film or great novel, or first glance at a beautiful piece of art.

By the way, my oldest daughter just got back from Europe and one of the highlights of her trip was a visit to the Dali Museum in Barcelona — which made me SO jealous.

And, of course I meant “Nikola” Tesla — I hate it when I type so fast.

Compare is a basic critical move, yes of course, but with comparable categories. So I can compare Tardi –or Sacco– with Kurtzman, but without forget the different categories/frameworks (historical-industrial-audience).

Let me say I wasn’t missing the point just because I disagree. I’ve already read this kind of criticism, and not only on Kurtzman or EC Comics.

But the topic is now Kurtzman’s EC comics, OK. As R. Fiore argued, Kurtzman worked in the 1950s within a framework of entertainment, in a commercial industry that produced a lot of stuff per month. Mainly for young people, I insist. So basically Kurtzman had to make entertainment for young people, with short deadlines. And despite all that, he worked to bring a new sensibility to war comics, and certainly he also contributed with significant formal achievements, yes. Not everything is ‘content’, form is very important, in fact form is also content, all we know that, right? And Kurtzman’s formal contributions in those war comics are so important to achieve certain tone and point of view that, for instance, three decades later Dave Gibbons would go to them to devise his ‘fixed grid’ in order to set the tone for Watchmen.

Besides this, to tell you the truth nowadays I find this kind of criticism in comics a bit out of time and repetitive. Like walking in circles. I’ve spent many years reading Gary Groth doing the same criticism, about the crappiness of most of the stuff, “in comics there are nothing comparable to the great works of literature and film”, etc. But he did it 20/30 years ago, with more nuances (I must say) and points to think about and discuss. I’ve read about the same subject in his interviews: with Denny O’Neil in the early 1980s, then with Gil Kane (Kane thought as Groth in this issue, more or less), arguing with the grumpy Alex Toth and many more. But Groth did this many years ago, when the North American comics remained largely stuck by the clichés and codes of old comics for children, and he wanted more variety in the subjects, more density and so on. In other words, more comics for adults, truly adults.

So this discussion today in these terms, now in the era of the graphic novel, with so many good comics for adults (also bad, of course) it seems a bit out of time. Like arguing about the same thing over and over again, for decades. And that’s also typical of comic book circles.

Right now I’m reading Alison Bechdel’s Are you my mother? With all the criticism that can be made, I think it’s a good job that resists any comparison with comparable material in the same category, in comics or literature.

So maybe for the Week of Love in HU we could read a review on the virtues of Tardi’s It Was the War of the trenches ; ) A book published in U.S. by the same publisher that has reprint the Kurtzman war stories, BTW.

Pepo: Thanks for commenting but I’m not quite sure how to respond to your objections. Noah has answered quite a bit so I’ll only add to his points.

In the first part of this two-parter, I quoted Al Feldstein as stating that, “Yeah, they were all right. If you start judging them as works of art, you’ll never get anywhere. Judge by the fact that they were comics books written for fourteen-year old kids, sixteen maybe…” I think Feldstein had a true but incomplete grasp of what he was producing in contrast to modern day comics critics who champion these works as some of the finest ever. I personally know 14 year olds who are making their way through Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky, and Tolstoy’s short morality (+/-Christian) tales are certainly meant to be read by 10 year olds. Fourteen is about the age when people start to read Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Le Guin,and things like Dune. Just how much allowance am I supposed to make for the credulity (I won’t use a more insulting word) of the average EC (child/teen/adult/whatever) reader?

I’ve read a number of the Ripley and Famous Five books and I would say that by any measure, the Ripley books are superior. And they absolutely can be compared even if one is about a serial killer and the other about a bunch of callow investigators. There’s nothing difficult about Highsmith’s prose. Anyone who can get through Feldstein and Kurtzman’s tortuous, ulcer-inducing prose should be able to handle it. I know you weren’t actually trying to do this, but inadvertently creating an analogy between the Famous Five and the EC comics line? If the EC line were only as highly regarded as the Famous Five, I would not have written this article. The article was first printed in The Comics Journal and EC occupies four places in their Top 100 Comics list. As stated in my opening paragraph, this article was partially written in response to that. All such lists can be seen to be flawed but would you be happy to see the works of Enid Blyton placed on the Modern Library 100 list?

ALSO, I have no doubt that Domingos will absolutely despise Spider-man #33.

Russ, if you wanted to write about that Spider-Man story for us, I would love to publish such a piece.

Domingos, re: Suat’s take — yes, you’re right. I was trying to say that Suat thought the EC comics were mediocre children’s lit, but I don’t think it came across right.

Also, if you like that Spider-man and I am forced to eat Russ’s comment, I will be displeased.

“Comparing Kurtzman’s children’s 50s war comics with Oesterheld’s children’s 50s war comics?” It’s OK, Domingos. Go ahead.

(personally, I prefer Kurtman’s)

Pepo: Well your most recent comment sort of makes things clearer for me. By your statements, it does appear that you feel that Kurtzman’s War comics are severely compromised by time and audience, and that outwith these parameters – these parameters being comics, time, audience – are 50s crap. While I probably disagree about the intelligence of the average 50s fourteen year old, within these parameters, I think we have no argument. I’ll keep an eye out for a time machine to better appreciate the EC line.

Pepo:

Suat on It Was the War of the Trenches.

Suat on Bechdel’s Are You My Mother.

“EC occupies four places in their Top 100 Comics list”.

English-language comics, if I remember well, and comics of 20th Century. No Tardi, no Oesterheld, no Asterix. So, yes, much of that history is made up of comics for children. We should already know.

“on the Modern Library 100 list?”

But the history of literature is not a history of children’s literature, not least because children’s literature is a modern invention. This is why I criticized the ahistorical thinking. Personally, I can’t understand the comparison between the histories of different art forms. The film has a different history in comparison with literature, and both are very different from the history of comics.

Suat’s point is that they are not very good children’s comics. Four mediocre children’s comics in the top hundred best comics of all time means either, (a) comics really, really suck, or (b) the mediocre children’s comics are overrated. Maybe you see a third option, but I don’t.

Again, cross genre comparisons are both very common and very fruitful. No two things are exactly like each other, but looking at similarities and differences can help you better understand both things you’re talking about. Again, comics wariness of these sorts of comparison suggests less judicious care, and more a fear that the artform will be found wanting.

Which is unnecessary, to my mind. The best comics are as good as the best art in any other form. Peanuts doesn’t need your condescension, damn it.

Pepo, the Modern Library 100 list is a list of English-language novels of the 20th Century. It’s pretty comparable to the TCJ list. Anyway, I think we can agree to disagree. You think comics should only be compared to comics and only of the same time period, and I don’t. That’s fine.

Noah wrote: “Russ, if you wanted to write about that Spider-Man story for us, I would love to publish such a piece.”

This comics philistine just may take you up on that. It won’t be for at least a couple of weeks though. I’ll let you know.

Now that’s how you hate.

“This is why I criticized the ahistorical thinking. Personally, I can’t understand the comparison between the histories of different art forms.”

There probably wouldn’t be any need to if there weren’t such a paucity of comics classics. What would be the point of comparing crap-to-crap?

That said, directly comparing the merits of the European war comics Domingos mentioned to the faults of the EC ones could make a great post.

“…may be anxious to dump content, narrative and dialogue into a bottomless pit reeking of nostalgia….”

Reeking of nostalgia and complacency, yes. This pretty much up sums up the mindset one comes across when critiquing the various comics industry sacred cows (take your pick).

“the Modern Library 100 list is a list of English-language novels of the 20th Century. It’s pretty comparable to the TCJ list”.

I mentioned Tardi and the other authors of non-English comic, that they can’t fit into a list of English-language comics.

“You think comics should only be compared to comics and only of the same time period”.

No, I didn’t say that. But it’s OK.

Anyway, you don’t need a time machine to understand a few things. You constantly compare with literary works, Tolstoy, Tolkien, whatever. But comics are not literature (at least I think so), and of course the comics were not perceived as such by the kids in 1950s. The comics have (pardon the obvious, but I think it’s necessary) drawings, not just words. It’s not a question of ‘difficult’ or easy language for a kid of 10-14 years, again we return to the different categories and the different form. It was the pleasure of seeing drawings, one after another. Drawings that build a story, something therefore not comparable to any novel. Then and now. We here speak of visual entertainment for children in the 50s. Television (black and white) had arrived recently in American homes. No Playstation, no Internet, no chat, no iPad, no nothing. The FX movie / tv still can’t afford to build compelling images that could be compared to that of many comic books. And, as comics for kids, as entertainment for young people, I do believe that Kurtzman’s are among the best of his era. If you think that those 1950s comic books, all those comics, are crap is another matter.

Argentinian, dammit! Oesterheld was Argentinian!

Sorry about that!…

Kurtzman’s war comics and Oesterheld’s war comics are very different. Kurtzman’s best stories have this symbolic (universal) appeal that’s quite heavy-handed (midcult). The only reason why I don’t consider them utter crap is because he was such a great cartoonist. (That’s one of comics’ great tragedies, by the way: the sheer quantity of great talent completely gone to waste.) Oesterheld did little morality plays. His best stories (he wrote some crappy ones too) are more about how human beings react in a stressful situation than about violent action. Plus: Hugo Pratt and Alberto Breccia were second to no one as cartoonists. Some of Oesterheld’s stories were drawn by a few second rate artists, unfortunately… He lost most of the talents working for his publishing house (Frontera) at the beginning of the 60s.

Just to contextualize a bit more, as Pepo wants: besides being a great writer Oesterheld was his own boss when he wrote Ernie Pike (a name inspired by American war journalist’s name Ernie Pyle; Hugo Pratt drew Pike with Oesterheld’s face). Maybe that’s why he wrote what he wrote, without major restrictions.

Re. the putative anachronism of Suat’s post: we just need to compare TCJ’s list with the HU’s list to see that no progress was made and Gary Groth’s concerns of long ago are still valid today.

Tim Hodler has a nice response to this piece here.

Reactions to this post on other quarters of the www are proof enough, if more were needed, that this artform is in permanent arrested development.

Domingos, I didn’t think you’d like the artists I cited as they are actually interesting and entertaining, my point was that you were making me want to quit reading European comics out of spite.

One thing that should give us pause…most of the EC artists were war veterans. They had seen war up close. Wallace Wood was a paratrooper. John Severin saw action in the South Pacific. Will Elder was caught in the Ardennes offensive– the Battle of the Bulge. Kurtzman was in the Merchant Marine, true, but this was an outfit that saw higher casualties even than the US Army.

Oesterheld never saw a day of combat…until, of course, he and his family were “disappeared” in one of the ugliest secret wars of the last century — the “dirty war” against so-called subversives under the Junta, as prescribed by the CIA in the pan-American ‘Operation Condor’.

Domingos:

‘Argentinian, dammit! Oesterheld was Argentinian!’

Yeah, but Argentinians are pretty much honorary Europeans, right?

I mean, it’s a chant that other Latin Americans mock, but which they take seriously: ‘We are Europeans’.

I love my Argentinian friends, but sometimes their attitudes are hard to take. Their snobbery towards other Latin Americans too often shades into racism. I’ve heard them call Brazilians ‘monkeys’.

A Mexican once defined the Argentinians to me thus:

“A bunch of Italians who speak Spanish, think they’re British, and act like they’re French.”

Harsh, but– gotta love’em.

But does having been in a war mean that you’ll create more meaningful art about war? Especially when you’re maybe not trying to create especially meaningful art so much as boys adventure stories, which seems like it’s the case for most EC artists?

Noah, I don’t know how much you’ve read of the EC war stories…but Suat, though honest, isn’t necessarily the best guide to them. They certainly can’t be qualified as ‘boys’ adventure stories.’

Nor should you necessarily consider me a good guide…though I wrote for this site a critique of the Kurtzman war tales, which Suat helped with (I don’t know how anyone has plumbed that man’s generosity):

https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2010/08/strange-windows-someone-had-blunderd-kurtzman-at-the-charge/

I haven’t read much of EC, honestly; every time I look at them, my eyes glaze over pretty much, I have to admit.

Noah — Accuracy- and empathy-wise, I would think that a soldier –especially one who has seen combat — would have a leg up on the armchair general or pacifist idealist when it comes to telling war stories.

There are exceptions, though, such as folks like Caniff, who spend their whole life continually researching the topic.

Hmm, when you say your eyes glaze over…could that be a generational thing, at least in part?

The idea that you have to go to war to be able to talk about it intelligently seems really problematic in itself. Again, I don’t know that it’s born out. The Red Badge of Courage wasn’t by a soldier (though I believe Crane worked as a war correspondent in some conflicts.)

Noah — I went around and around with Groth about this on the old TCJ message board about 3-4 years ago. He was of the opinion such experience wasn’t necessary (or even desirable!), but his arguments weren’t very convincing and smacked of pacifist intellectual hubris.

Stanley Hauerwas, who’s a pacifist, has a really interesting take on this. He argues, first, that military communities and institutions are among the few places in modern life where there is serious moral engagement in the problems of violence. He also says, though, that the tendency to believe that a serious engagement in violence can only come from military institutions — that moral force only inheres in the military, basically — creates a situation in which violence is sacralized, and in which it’s basically impossible to imagine non-violent options as moral.

I think that military folks absolutely have a vital and valuable perspective on violence and war, and I think that it would be very wrong to ignore that. At the same time, I think it’s both wrong and dangerous to say that military people are the *only* ones who can talk about war, or that their perspectives are necessarily more insightful or more valid.

it is pretty intolerable to read arrogant dismissals of “pacifistic intellectual hubris” by a career militarist.

M: “[…]my point was that you were making me want to quit reading European comics out of spite.”

So, I was citing Argentinian comics and you wanted to quit reading European comics. Ok…

…Oh, and your spite made you want to throw in the trash comics that I hate… double OK…

James…like I said, I think military people have important things to add to any discussion of violence. But pacifists do to.

Can’t we all just get along?

James — Anyone can be a pacifist and know-it-all when they live in a sheltered society. In unsheltered societies like North Korea or the Sudan, they don’t last long because they are at the mercy of people who don’t know the meaning of reason, compassion, or fair play. For example, if Ghandi had tried his pacifist movement in 1933 Germany or Russia, no one would have ever heard of him because he would have been purged along with every other person who made the mistake of getting noticed by the ruling parties.

Yeah…see, that’s all nonsense, Russ. You’re not speaking from your military experience; you’re spouting stale talking points. Anyone can do that.

I’ll point out a couple of things.

— the assumption that British India was not a seriously oppressive society is pleasant for those of us who identify with Anglo-Americans and our lovely democracy. But oppression is oppression wherever it is, and just because we think of the British as good guys and the Russians as bad doesn’t mean that we should get to belittle the courageous folks who fought for freedom by telling them that they had it easy. You’re essentially calling Gandhi a disconnected pacifist and know it all…which seems really insulting and profoundly stupid.

— pacifism has nothing to do with why North Koreans are oppressed. It’s true that Gandhi might not have been successful in N. Korea…but there’s no reason to think that Che would be successful either. People in those countries are oppressed not because they have a commitment to nonviolent resistance, but because they’re oppressed. There’s no reason to think that violent opposition to the regime in North Korea would go any better than passive resistance. There’s in fact plenty of reason for thinking that it might go worse.

— Burma just accomplished a basically peaceful overthrow of a severely repressive regime. It got much less press than the violent overthrow of regimes in the Middle East…but that’s in large part because it’s been more successful, right? The insistence that only violent resistance counts is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

‘There’s no reason to think that violent opposition to the regime in North Korea would go any better than passive resistance.’

But, Noah, yes there is. It’s called the Korean War. It saved the southern half of Korea from the hell of the North’s regime.

BTW, Gandhi refused the name of pacifism: he preferred non-violence.

Well, I was talking about internal resistance, obviously.

And it’s always hard to figure out counterfactuals, is the truth. The Korean war killed an awful lot of people, and the result is that half of that country has been under a truly heinous dictatorship for more than 50 years. That doesn’t seem like a sweeping, awesome victory to me, exactly. Vietnam, where violence was unsuccessful and the communists won is actually in significantly better shape at this point, it seems like.

I think there are certainly failures of pacifism and/or non-violence, and those are difficult issues for anyone who supports non-violence to grapple with. But arguing that violence is a significantly better answer by pointing to various authoritarian regimes isn’t especially convincing, inasmuch as the world order we live under is not especially pacifist, and yet there are really quite a number of authoritarian regimes kicking about.

Can we get along? Here’s my take on the hatefest in a word: barf

Very much in the spirit!

You liked Jason Overby’s piece, though…Facebook told me so.

Noah:

“And it’s always hard to figure out counterfactuals, is the truth. The Korean war killed an awful lot of people, and the result is that half of that country has been under a truly heinous dictatorship for more than 50 years. That doesn’t seem like a sweeping, awesome victory to me, exactly. Vietnam, where violence was unsuccessful and the communists won is actually in significantly better shape at this point, it seems like.”

I had to re-read this a couple of times to puzzle out the weird pseudo-logic involved.

‘The Korean war killed an awful lot of people, and the result is that half of that country has been under a truly heinous dictatorship for more than 50 years. ‘

No, the result is that half of that country has NOT been under a truly heinous military dictatorship for more than 50 years.

“Vietnam, where violence was unsuccessful and the communists won is actually in significantly better shape at this point, it seems like.”

No, Vietnam, where violence was SUCCESSFUL — the violence of the Viet Minh, the Viet Cong, and the NVA — is actually in significantly better shape at this point.

Noah, I’m being charitable– you just aren’t thinking through these posts.

Hey, guys, I’d jump into the fray, but I’m in Vegas. Suffice to say, Noah, I’ve though it through for decades, and my conclusion is that while non-violence can work under very controlled conditions, in most cases, when the adversary does not care about civilized nicities, pacifists are nothing more than a speed bump.

Diplomacy should always be the first option, but if it fails, one had better be able to defend oneself through force.

Russ Maheras wrote: “while non-violence can work under very controlled conditions, in most cases, when the adversary does not care about civilized nicities, pacifists are nothing more than a speed bump.” Um, Russ, if you think the British played by the rules of “civilized nicities” in India you really don’t know the history of that country. I would suggest you read Mike Davis’ Late Victorian Holocausts (which deals with Ireland and other colonies as well as India) and Madhusree Mukerjee’s Churchill’s Secret War: The British Empire and the Ravaging of India during World War II. Both books document the use of famine as a weapon of rule — a weapon that resulted in millions of deaths — and give lie to any fantasy of the civilized nature of British imperialism.

Also, while I love Caniff, the idea that he accurately represented military life seems incredibly credulous. Caniff deliberately and for the best of motives made himself into a propagandist for military value. The results were often cringe-making. Take a look at Caniff’s “How to Spot a Jap” and tell me that Caniff was a realist: http://www.ep.tc/howtospotajap/

Alex, obviously if there’s a winner and loser, violence is successful for somebody. I was referring to US violence as the basis for success or lack thereof.

Violence did help preserve South Korea…but would a nonviolent solution have had a better long term effect for both South and North? It’s just really difficult to answer those questions. Same with, say, the Civil War (as an even more difficult issue for pacifists.) It’s true that freeing the slaves had to have been about as just a reason for violence as one can really imagine. And yet, the aftermath of the civil war resulted (after the brief spring of Reconstruction) in what was arguably even worse racism in the north and another 100 years of oppression in the south.

I think in general peaceful efforts tend to result in better outcomes; less bitterness, less authoritarianism, less people killed. Though even there…Russia had a peaceful end to Communism…and they still have an authoritarian government.

My point is basically that when you denigrate pacifism as a solution, it’s usually done by conveniently forgetting all the ways in which violence often fails, or doesn’t work. The pragmatic argument for the virtues of violent solutions have to ignore an awful lot of violent failures…not to mention all the bodies.

And…what Jeet said about the civilized nature of British imperialism (or of Jim Crow in the US, for that matter.)

Is Russ’s opinion informed by the risk of life and limb in combat, or just by years of experience as a PR guy (“entertainment liason”) for the Air Force?

I don’t know what Russ’ experience is…but I actually would be interested to hear him talk about how his military experiences (whatever those may be) have affected his take on pacifism and violence. Russ, maybe you can talk about it a bit more when you’re back from your trip?

I’ve been thinking for a while about doing a roundtable on pacifism and violence, maybe centered around some of Niebuhr’s writing. Hopefully we’ll get to it one day….

A few scattershot comments (maybe with the war theme here, we can call them “shrapnel”:

Of course Sacco’s reporting, Tardi’s WWI stories are vastly better — more complex, harrowing, “adult,” far greater works of art — than the EC war comics line.

A significant factor in their strength is that the former are grimly unvarnished true stories; reality by its very nature being far more complex, ambiguous than anything a fictioneer can come up with. While EC’s war comics are either fiction, or highly simplified views of reality, structured to provide a satisfying finale or moral within a few pages.

————————–

Pepo Pérez says:

…why compare something that was conceived at the time (1950s) as entertainment for young people (kids of the 1950s, remember) with Apocalypse Now, which was not designed for “kids” neither as ‘entertainment’ (the 1970s New Hollywood) ?

…Even more, why compare EC war comics with Tardi’s It Was the War of the trenches, a work made for another market/audience, another historical moment (1980s), with other publishing formats (which didn’t exist in the 1950s comic book industry and were not even conceivable at the time, nor Kurtzman would have allowed to use them) and, above all, a work designed for a different type of audience, adult audience?

———————-

Indeed so! A more proper comparison would be EC’s war comics against Marvel’s “Sgt. Fury and His Howling Commandos” and DC’s war comics, decades later; the work of other mainstream comics publishers, aimed at a similar audience. And there, EC is like gold compared to brass…

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Pepo…Are you saying it’s never okay to compare works across time periods or cultures? Surely that can’t be right; I mean, one of the way people — artists, critics, everyone — thinks about art is by comparing and thinking about how different works compare or contrast with each other.

———————–

Sure. But, it’s also absurd to damn a fine work (say, “Where the Wild Things Are”) to perdition because it fails to measure up to the criteria by which Shakespeare’s poetry, or Strindberg’s drama, would be evaluated.

Sendak’s book is about as perfect a work of art as could be asked for; yet — if you were to judge it by standards utterly inappropriate to its target audience, authorial intent, it’s philosophically and psychologically simplistic (the grand theme would be, “there’s no place like home”), comforting (Max is never in any real danger; those “wild things” are wusses!,/i>)and status-quo reinforcing.

————————–

Ng Suat Tong says: