At first, I was nervous. I am not a hater by nature; I generally consider myself an enthusiast. How could I, then, participate in this Festival of Hate? Is there a way to responsibly choose something that’s worth hating on? Perhaps, I thought, I should just refuse to participate all together.

Noah asked me to pick my candidate for Worst Comic Of All Time. Being a good graduate student, I decided I needed some kind of rubric for determining Worst. Whatever I chose had to (A) Be made by competent, even skilled, creators (Ed Wood style badness wouldn’t do!), (B) Fail on its own terms to the extent they can be determined by a good-faith reading of the text, (C) Be not only bad but hateful in some way and (D) Influential.

There were several candidates that leapt to mind, but were unable to fulfill all four. The 300, for example, is hateful, made by a skilled creator and influential. But it doesn’t fail on its own terms. It is trying to be The Triumph of the Will of American Empire, a racist, pro-fascism pamphlet in which Western Society is attacked by ever darker, more exotic and queerer antagonists. On this front, it succeeds. It is, as a friend of mine put it, “a delicious pie baked by Goebbels.”

This search eventually lead me to Alan Moore and David Lloyd’s V For Vendetta, a work that fulfills all four criteria with aplomb. It’s a competently made, terrible, hateful failure on its own terms that has, sadly, had some influence, particularly on the radical left, who really should know better by now. It manages to be brazenly misogynist, horrifically violent, and thuddingly dull all at the same time. It’s one of the few books that spawned a film adaptation that is both borderline-unwatchable and an improvement on its source[1]. Moore and Lloyd appear to have set out to make Nineteen Eighty-Four with a happy ending, and instead ended up making a leftish The Fountainhead.

For those not in the know, V For Vendetta is Alan Moore’s first longform work with original characters. An anarchist response to the election of Margaret Thatcher, V takes place in a fascist England after the whole rest of human civilization has been wiped out in WWIII[2]. Seemingly out of nowhere arrives V, a faceless terrorist who wears a Guy Fawkes mask and pursues two goals: revenge on the people who imprisoned and medically experimented on him in a concentration camp, and bringing down the government.

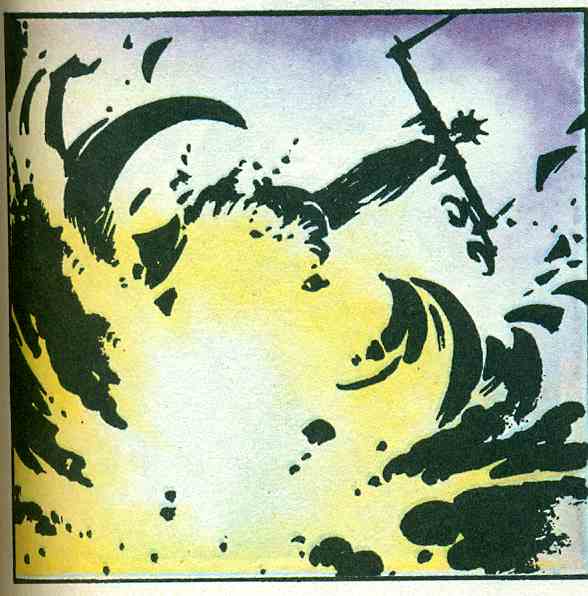

The book sets out to be a kind of action-thriller with political content, a work that uses a compelling story and the basic tools of mainstream comics (read: violence) to smuggle in a lot of pro-anarchism speeches and “thought provoking” sequences about individual and political freedom. On both of these fronts, it fails massively. It does not work as a thriller because we are never as readers in any doubt that V will succeed. He assures us again and again that he has a plan and at no point in the book does this plan seem in any kind of jeopardy[3]. He suffers no setbacks. He in no way struggles. Everything moves forward with the inexorability of a Greek Tragedy, but one that takes the gods’ point of view instead of the mortals. This sabotages any potential thrill the story might have as a story. Narrative tension generally relies on some mix between questions the audience needs answered and answers the audience has that the characters don’t. Neither is present in this book. The mystery as to V’s origin—really, the only even mildly compelling question in the text—is resolved before the first third is over.

The political content, such as it is, is no great shakes either. Yes, radical anarchy is preferable to jackbooted fascism. And in a world in which sanity means conformity to a genocidal, hyper-consumerist, corrupt authoritarian society, maybe we all need to go a little mad. V, however, ends just before fascist England actually falls. Moore gets to have it both ways, making a case that a radical anarchist state would be a really great thing without ever having to imagine for the reader what that world would look like. He even has V go to great lengths to explain that the riots, looting and murder taking place in England’s streets as the government collapses aren’t anarchy at all, but rather chaos. I suppose anarchy, like Communism, can never fail; it can only be failed.

The problem with shoddy political allegories like V For Vendetta (or The Dark Knight) is that the alternative realities they rely on to make their experiments work are so preposterous and rigged that they end up disproving themselves. True, were England to be taken over by Nazis, terrorism would likely be justified. But making a book arguing this case is a waste of time and energy. You might as well write a book making the in depth argument that if your Aunt had bollocks, she’d be your Uncle.

Well-crafted dystopian narratives understand this. Nineteen Eighty-Four doesn’t spend a lot of time arguing to the reader that the INGSOC should be overturned. Neither does Brazil contain a stemwinding speech about the tyranny of bureaucracy that Sam Lowry toils under. Instead, both bring to the table a rich examination of the psyche of those living under a dystopian state. Sam Lowry’s inner conflict between being a distracted dreamer and a bureaucratic climber slyly interacts with his gradual education into how his world and privilege work. Nineteen Eighty-Four’s portrayal of the gradual wearing down of Winston Smith’s psyche and of the way the totalitarian mindset is formed and reinforced at every turn, is harrowing and moving[4].

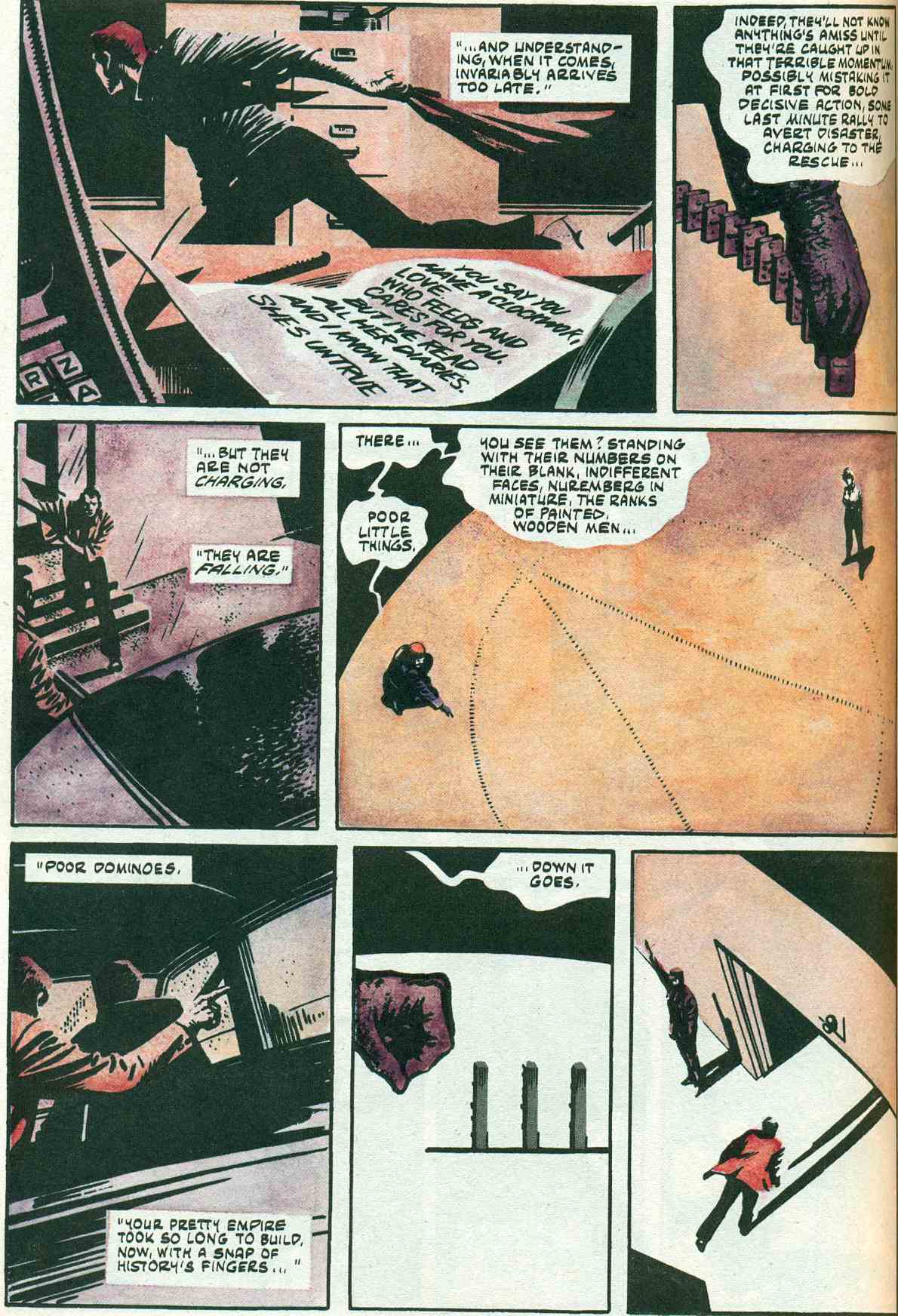

In order for V for Vendetta to pull something similar off, it would have to care about the characters who inhabit it. Sadly, the souls wandering its richly illustrated pages are mere pawns—or, to use the book’s own recurring image, dominoes—they are there to be set up and moved around as the narrative sees fit, toppled when expediency demands.

Nowhere is this more true than in the work’s treatment of Evey Hammond, V’s female sidekick[5] and eventual replacement. Evey is a shopworn narrative trope, the neophyte who joins the narrative so that the world can be explained to her, and via her, the audience[6]. Evey is the reader-surrogate within the novel, the person who has to try to make sense of V’s actions, while V is placed as the author’s surrogate, the explainer and shaper of the narrative. Repeatedly, we are reminded that V is creating something for us, something that seems chaotic, but that will reveal a pattern if we just wait and are patient. For example, this section comes from a journal of one of V’s “doctors” at the prison camp:

While later on, we see a recurring image of V setting up dominoes in his home base without being able to see the pattern, only to have it be revealed that it is his trademark V symbol right before he topples them all and the state of England:

If Evey is meant to be the reader and V is meant to be creator, it’s worth pointing out exactly how V For Vendetta’s creators feel about their audience. “I’m a baby,” Evey says to V. “I know I’m stupid.”:

V for Vendetta is the kind of book that proceeds from the assumption that the reader is a moron, and if only we were properly enlightened, we would agree with its creator. We are the gutless conformists, who just need a good stern talking to (and a little bit of torturing) to convince us of our errors. And here comes a guy who talks a lot like Alan Moore—all allusions and quotes from other sources, weird obscure jokes and puns, cryptic clues—to show us the way. It is, in that way, no different from The Newsroom: the work of a blowhard who is incapable of imagining anyone ever disagreeing with him, or a world in which he could possibly be wrong.

I suppose this shadow agenda of proving Alan Moore smarter than us would be all fine and good were the book to succeed in it. Sadly, amidst all that allusion and reference there’s a glaring neon sign that V for Vendetta is not nearly as smart as it thinks it is:

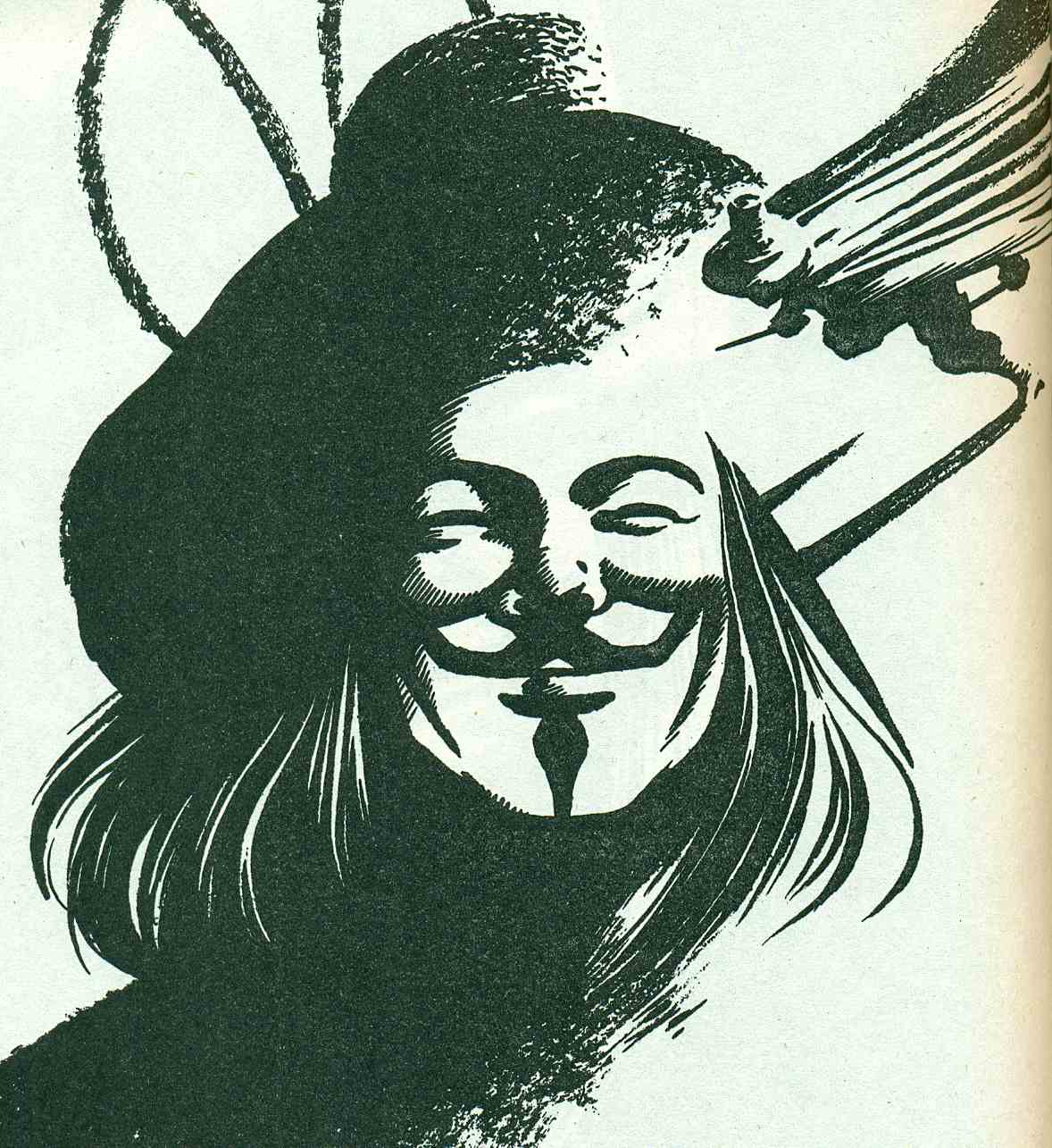

That’s our man V there. He’s wearing his trademark Guy Fawkes mask. Guy Fawkes is the book’s symbolic hero. Lloyd mentions in an afterward that he wanted to rehabilitate Fawkes because blowing up parliament was a great idea. But—and I hope this is obvious to many of you when you stop and think about it—it’s patently absurd to take Guy Fawkes as an anarchist-leftist superhero. Fawkes was a ex-soldier and Catholic extremist trying to overthrow an authoritarian anti-Catholic State and replace it with an authoritarian Catholic one. It’s just plain dumb to borrow the symbol of Fawkes without the slightest care for what it represents, just as it is an act of idiocy for the hacker group Anonymous and various members of Occupy—a movement I support, I hasten to add— to adopt the Fawkes mask as their icon.

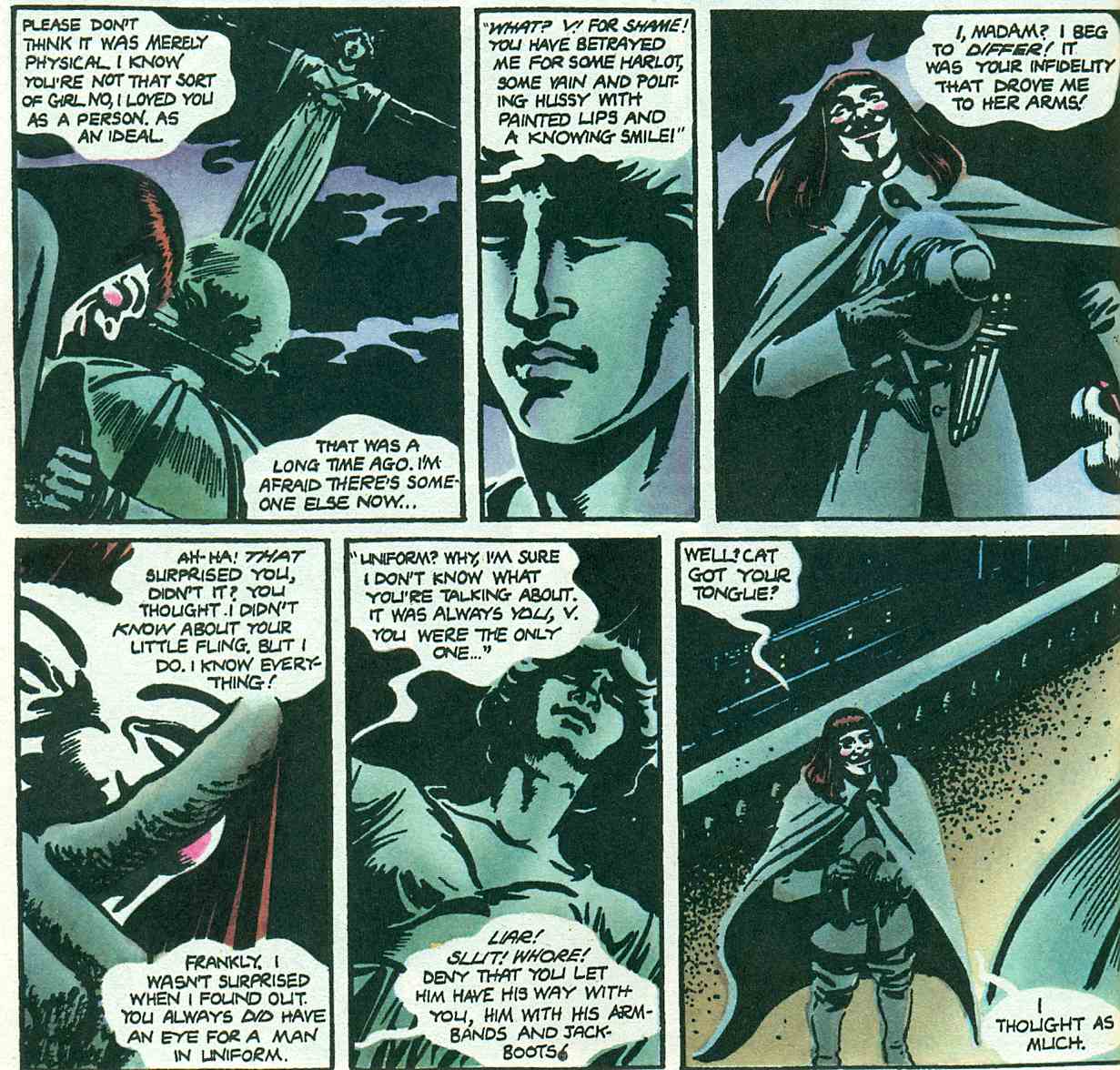

As the book wears on (and on, and on) it also gets derailed by its panic and anger at female infidelity, a crime that is punished with gleeful violence at every turn. On pages 39-41, V recasts his quest to free England as a lover’s spat with the female statue of Justice, who has cheated on him with Authority:

Care to guess how it ends?:

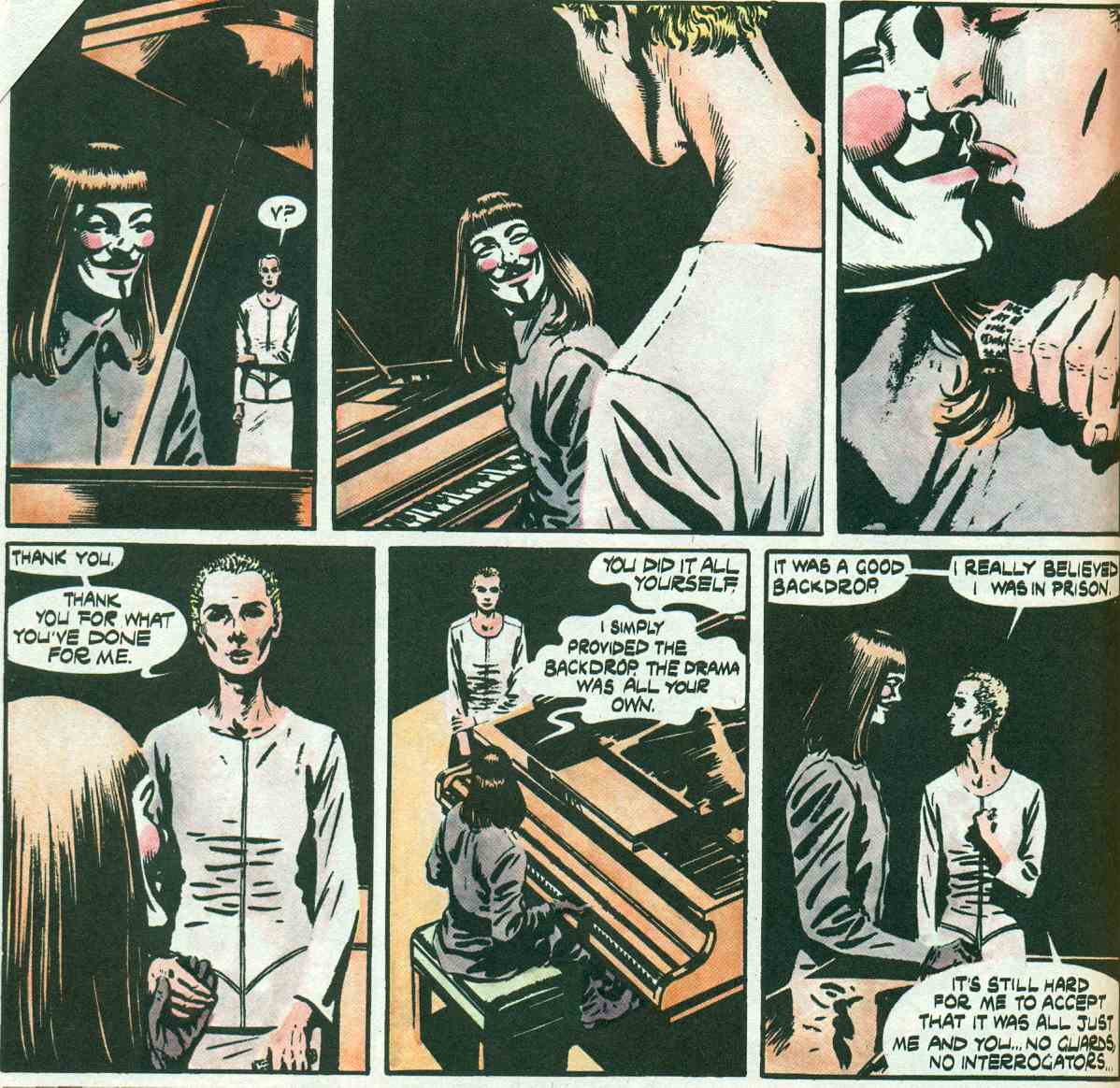

When Evey propositions V, he abandons her on the streets of England. Having nowhere else to go, she briefly takes up with a liquor smuggler named Gordon. With the inexorability of an early-eighties horror movie, as soon as she has sex with him, he gets killed by gangsters. After this, she is kidnapped, tortured, and interrogated, as faceless interlocutors demand to know the location of V and his plans. At night, she reads a letter from a fellow inmate which gives her the courage to accept death rather than betray V. It is then revealed that the whole kidnap/torture/interrogation thing was an elaborate ploy by V to set Evey free by helping her get down to the individual freedom that exists within us, the last thing that we control. While initially upset, here’s Evey’s eventual response from page 174:

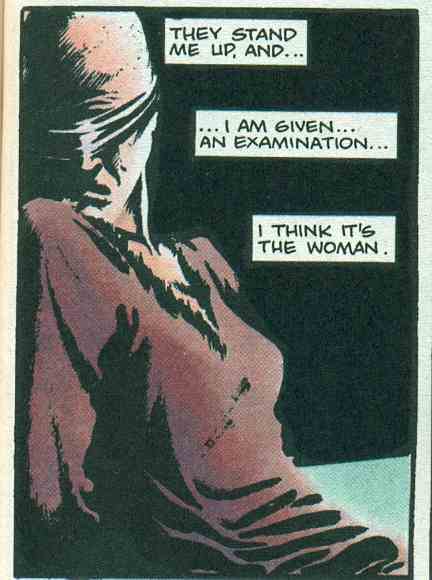

This would be hard enough to swallow were it not for the fact that Evey’s incarceration included sexualized imagery:

And actual sexual assault:

You see, dear reader, if you won’t see the light, we have the freedom, as filmmaker Michael Haneke put it, to rape you into enlightenment. Stockholm Syndrome is liberty. Also, War is Peace and Ignorance is Strength. Just shut your pretty little mouth and do what the author tells you. Never you mind that this is supposed to all be about radical individuality being the only way forward. You are radically free to agree and that’s about it.

Finally on the docket of cheating women who need to be punished, we have Helen Heyer. Helen becomes a regular presense in the third act of the book, as the (oddly fragile given that it’s supposed to be frighteningly all-powerful) society crumbles. The wife of a high-ranking fascist, Helen tries to maneuver her husband into the role of Leader by sexually manipulating his colleagues. She also refuses him sex. Helen is a classic misogynist caricature, simultaneously frigid and a whore, using her body to get ahead. It doesn’t work, of course. V sends her husband a videotape of her sleeping around, he murders her lover and is killed in the process. Helen’s plans come to naught and the book’s supposedly-cathartic orgy of chaos and violence ends on the final page with her about to be gang raped by hobos because she’s sick of trading sexual favors to them for food. Seriously. That’s the book’s ending.

All of Moore’s bad habits as a writer are on display in V, from its misogyny to the stentorian, hectoring tone of the text whenever its eponymous hero shows up to its frantic, desperate need to impress us with its creator’s brilliance. I feel I’ve only really scratched the surface of V For Vendetta’s terribleness here. Part of me was tempted to simply scan the song on pages 89-93 and write “Game, Set, Match,” underneath, or discuss the hackneyed and emotionally manipulative story about what happens to one of the prominent fascists’s wives after he dies, how she comes to miss his physical and emotional abuse when she has to take up a stripping job for money. Or catalogue the way in which each allusion—to everything from MacBeth to Sympathy for the Devil—is constructed not because of its actual relation to the material, but because it’s impressive.

Instead, let me close on a personal note. The reason why I find V For Vendetta so upsetting, the reason why it makes me so angry, is on some level political. I am a leftist. Unapologetically so. That V For Vendetta—with its nihilistic embrace of violence, it’s distrust of the institutions that will be required to enact any lefty agenda, its hatred of women and its love of coercion— has caught on amongst lefties, that in particular Guy Fawkes has been taken as a symbol of anything other than far-right religious terrorism is something I find particularly galling. I worry that at heart some of my fellow travelers on the Left feel reified by this work’s subtextual assertion that anyone who disagrees with them must be blinkered, an uninformed idiot who simply needs to be enlightened or blown up.

I suppose there is another way to read V, one where the surface and subtext are actually in constant conflict. One where the first chapter’s title (The Villain) is meant to be taken more seriously, where we are meant to see Evey’s torture not as she comes to eventually see it, but for the problematic and rapey coercion of one who disagrees with our main character. Maybe we are meant to see the downfall of the state as a complicated thing, and the gang-raping hobos not as a darkly ironic enforcement of Moore’s id but rather as a sign of complexity in the work. Perhaps V’s anarchist utopia is never shown because utopia means no-place and V is, in fact, wrong. Certainly there are panels and excerpts one could use to make this argument, but I am not the one to make it, nor would I really be convinced by that argument. It’s a bit too clever by half, a way of taking the book’s considerable weaknesses and claim them as strengths. Besides, Moore does a far better job in Watchmen of having the character whose worldview is closest to his also be a monster who does something unforgiveable for “the greater good.”

[1] This is almost entirely due to the presense of Stephen Fry

[2] Somehow this authoritarian hellscape on an isolated island nation with limited land and resources also manages to have a hyper-advanced sci-fi surveillance state and all of the middle class comforts of late twentieth century life, but there’s so many bigger problems with the text, we should probably let that one slide.

[3] V’s plan, by-the-by, is implausible within the world Alan Moore has constructed. We’re meant to believe that V, an escaped political prisoner, has somehow managed to amass a huge fortune, a wide network of real estate, hacked into Fate, the central computer that oversees all surveillance and activity within England and designed a meticulous plan to bring down the Government in under 5 years.

[4] Both also try to create analogues for our own time within their world, things that feel both exaggerated and frighteningly real at the same time. Brazil begins with a typographical error leading the State to torture and murder the wrong man, which feels ridiculous until you recall Maher Arar. Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Two Minutes Hate isn’t exactly Talk Radio, but it’s not not Talk Radio.

[5] You could argue that Evey is the protagonist of V and V the mentor figure. I actually think the book is confused about who its main character is. V doesn’t change, so he makes a shitty protagonist. Evey changes but is so thinly rendered and boring you can feel the book wanting to focus more often on V.

[6] Think Ellen Page in Inception.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.

This is a righteous takedown, and I agree with a lot of it (as I discuss in this post from way back when.) I think you’re analysis of the book’s misogyny is particularly damning.

I still have more affection for the book than you do, though, Isaac. I don’t think that the Guy Fawkes mask is as much of a knock-out blow as you seem to; symbols often get reinterpreted or reappropriated in different contexts.

I also guess I still find that note Evie finds really moving. Though, of course, in some ways that just makes the book worse, since it turns an extremely eloquent anti-torture appeal into an excuse for torture…I don’t know. Like I said, still conflicted, but I think you’ve convinced me that the book is worse than I’d thought (and I had thought there were serious problems.)

Hey Noah,

I agree with you about the letter, actually. It’s the one glimmer in the book and it might be on a prose level one of the best thing’s Moore’s done. In the interest of fairness I probably should’ve said that.

Of course symbols can be reconfigured, but this particular one is deeply stupid. Moore and Lloyd take one kind of terrorism and use it as a symbol for another simply because they’re both terrorists and in the early eighties, terrorism was kinda cool. There’s no actual effort to reconfigure the symbol, they just seem to assume that Fawkes makes a good totem for V, but they stood for opposite things. I don’t consider this a knockout punch however, just the most constant evidence of the book’s idiocy. The song is tied for stupidest thing in the whole book with V driving the leader insane by convincing him that the Fate supercomputer (a) loves him and (b) has cheated on him but I didn’t want to try the reader’s patience by detailing every boneheaded thing in the book.

Haven’t had too much time to think about this and haven’t read V for Vendetta in nearly 20 years but I think I agree with Noah. The comic has never bothered me as much because I’ve always viewed it as an adventure comic steeped in superhero tropes. The fact that the mask from the film has been co-opted by some in the Occupy movement sort of makes this reading more important though. It’s a bit like the debate between Black Power and the non-violence movement during the 60s.

The counter argument you represent in the final paragraph does hold water though. I don’t know what Moore’s politics were at the time but there’s some (?) reason to believe that while V started out as a revenge fantasy, it ended up a compromised but nasty portrayal of both fascism and anarchy. V is Judge Dredd for the liberal masses. It depends on how much sophistication you want to attribute to Moore. For comparison’s sake, wouldn’t you say that the one person in From Hell who seems closest to Moore in terms of beliefs is actually William Gull?

I think Moore got a lot smarter about this stuff later on. Ozymandias is the liberal do-gooder in Watchmen, and you’re clearly supposed to see him as a monster.

But…because Moore worked these issues out better in later works doesn’t necessarily mean that he was on top of them in V….

There’s also this interview given by Moore:

“Moore: …Whereas, what I was trying to do was take these two extremes of the human political spectrum and set them against each other in a kind of little moral drama, just to see what works and what happened. I tried to be as fair about it as possible. I mean, yes, politically I’m an anarchist; at the same time I didn’t want to stick to just moral blacks and whites. I wanted a number of the fascists I portrayed to be real rounded characters. They’ve got reasons for what they do. They’re not necessarily cartoon Nazis. Some of them believe in what they do, some don’t believe in it but are doing it any way for practical reasons. As for the central character of the anarchist, V himself, he is for the first two or three episodes cheerfully going around murdering people, and the audience is loving it. They are really keyed into this traditional drama of a romantic anarchist who is going around murdering all the Nazi bad guys.

At which point I decided that that wasn’t what I wanted to say. I actually don’t think it’s right to kill people. So I made it very, very morally ambiguous. And the central question is, is this guy right? Or is he mad? What do you, the reader, think about this? Which struck me as a properly anarchist solution. I didn’t want to tell people what to think, I just wanted to tell people to think, and consider some of these admittedly extreme little elements, which nevertheless do recur fairly regularly throughout human history. I was very pleased with how it came together. And it was a book that was very, very close to my heart.”

It’s pretty clear the book undermines its own message at the end with the bleak final two pages though I think you sort of acknowledge that in your essay.

Not sure what to make of the misogyny accusation. It’s clear prisoners in real life really are sexually assaulted and/ or given cavity searches and the like, but it happens in real life is not really a defense, as an author makes all sorts of choices to accentuate or minimize realism when creating a story, and of course you can’t really say the book is realistic. I think the best defense I can muster is simply to say Moore does seem to care about Evie which is really just an argument that the misogyny is tempered, maybe?

The sequence with the justice statue is just so silly and theatrical I can’t take it seriously enough to say its misogynist.

The medical exam thing I guess would maybe be less damming if these sorts of things also happened to male characters, I guess? V’s own prison sequence is treated as dehumanizing but also empowering.

I think Moore in real life has said he’s a pacifist, though of course like most comic writers he writes stories about people hitting people- so you would never know that from his works. But calling this the leftist Fountainhead seems pretty hyperbolic.

“It does not work as a thriller because we are never as readers in any doubt that V will succeed.”

Isn’t it a given in most hollywood movies that the protagonist will win? Does that make these movies not exciting?

And yeah, of course the deck is stacked in favor of V, it’s really I guess just kind of an edgy pulp story. The villains are pretty much always morons in virtually any pulp story you can imagine, they never just shoot Batman with sniper rifle or nerve gas or whatever, because then the story would be over. The villain can never just shoot Bond when he has him captured.

That’s interesting as to his intentions…but I think Isaac has him dead to rights in saying that he largely failed. Moore is always trying to work with genre tropes and undercut them…and V is a place where I think the genre tropes (violence and misogyny, most notably) kind of kick his ass.

He needed to do more than have rounded fascists and show V murdering people. He needed to have Evey actually challenge V’s ideology effectively, both in words and in actions. He never does that, and as a result I don’t think the book says what he claims it does in that interview.

Don’t you think that would have made for a very banal and moralistic read? Instead he shows us the attractions of power and the pliability of the masses – the way libertarianism got turned into the Tea Party these past few years for example.

“Somehow this authoritarian hellscape on an isolated island nation with limited land and resources also manages to have a hyper-advanced sci-fi surveillance state…..”

I’m not quite sure if you’re being sarcastic with the above statement. His depiction of an island surveillance state has proved to be quite on target.

Like others, it’s been years since I’ve read it. I remember liking it, but that rape and torture sequence you described was quite troubling, needless to say. And the ludicrous reveal that “V” was behind it.

I think Moore to some degree revealed his politics in the brief afterword to the series where he denounced Thatcherism in a quite histrionic way. That’s the only other thing I remember about the whole thing.

Real quick cause they’re about to make

Me turn my phone off:. The book posits that England is the only

nation to have survived a global thermonuclear war. That’s why it’s highly

evolved surveillance state and general middle class lifestyle are preposterous. I wouldn’t care about this that much (world building isn’t my thing) but Moore brags about the plausibility of V’s England in the book’s afterword.

On the narrative tension front, good thrillers make us forget that the hero’s success is almost certainly a foregone conclusion. Or they put us in suspense as to what success actually means. Or they make the cost of success feel real.

Suat, the book is already moralistic and dull. Putting in some kind of actual dialectic wherein V’s constant lecturing could be argued against would probably

make it more interesting.

Suat, I don’t think so…because I’ve read (for example) Pygmalion, where the catspaw gets to actually criticize her manipulator. Far from being banal and moralistic, it takes moral issues sufficiently seriously to articulate them.

Watchmen isn’t boring either, FWIW.

…and of course Isaac beat me to it. So it goes….

“Of course symbols can be reconfigured, but this particular one is deeply stupid.”

Yo, I actually think taking an image of theocratic right-wing fervor and re-appropriating it tabula rasa in the service of leftist causes is a particularly brilliant example of detournement. It’s always possible that I am “deeply stupid” or “idio[tic]” though.

Pingback: Rhymes With Cars & Girls

Hey JH,

I’m not calling people who disagree with me stupid or idiotic. I am pro disagreement. I also don’t think that you can simply take a symbol and say it means something different than what it means and presto-chango, rearrango you’ve succeeded. Also, not that stated creator intent is the be-all and end-all here (i’m actually kind of opposed to reading things through what the creator says about them) but David Lloyd doesn’t seem to think that’s what they’ve done. He says in some of the endmatter that he suggested the Guy Fawkes mask because he thinks Fawkes the historical figure got a bad rap and that blowing up parliament is awesome. Now of course, David Lloyd could’ve been being sarcastic, or could be being stupid and the work could still achieve the thing you’re talking about here, but I don’t see a lot of work within the text itself centered on achieving the kind of detournement you articulate here. Do you? Or is simply by using a symbol that means X to instead mean Y enough?

I’m not British- is anyone here British? A valuable question is what’s the context of the Guy Fawkes mask in British culture? I thought they have a Guy Fawkes day which is sort of Halloween type celebration- not necessarily more relevant to the original event than the Salem witch trials are to a girl dressed up as a witch trick or treating in America?

I admit I’m kind of ignorant about it though, and have no idea if I’m right. Remember this book was originally made just for British audiences.

In the context of the book V has a lot of movie memorabilia and such- he just seems to be dressed as a theatrical character the specific costume doesn’t seem all *that* relevant, though he does reference Guy Fawkes of course.

Isaac,

You’re right. I was hasty in making the comment because I thought your piece was moralizing and I made claims I couldn’t really support.

The only defensible ground that I have to fall back on here is that your critique of it as a symbol of Occupy, Anonymous, and leftist activism today in America is misplaced. How many people do you think identify Guy Fawkes with religious extremism in America today? How many do you think identify him with leftist activism? Moore and Lloyd’s usage of him at the time was sloppy, but events since have made V for Vendetta the primary context for the Fawkes mask in mainstream culture. Fawkes the historical actor takes a back seat. I’m comfortable saying that the creators of V for Vendetta picked an obscure enough image and took advantage of the lack of historical context most people (at least in america) have for that figure to reassign it a new value. Much like many contemporary theorists appropriate old aristocrats and authoritarians for leftist causes (see Nietzsche-Deleuze or Zizek-Lenin), and similarly the Fawkes case (consciously or not) provides us with an interesting commentary on the ability for those of us who don’t insist on privileged representations (including authorial intent) to reinscribe conservative icons in our own projects. Though based on the amount of Orwell that you appealed to I’d understand if you found that somehow distasteful.

I think the idea here is that Guy Fawkes’ reputation is complicated – anarchistic terrorist, Catholic villain, source of religious hatred, popular hero, ritualistic effigy disconnected from religious content etc. Don’t think the reaction was meant to be (exclusively) Guy Fawkes – cool modern day hero. I suppose in that sense, the choice was too complicated for the eventual American audience?

We do get a little of David Lloyd’s opinion about the work, as you note, from the afterward, but I’m wondering if you see the artwork in this visual medium as having any particular effect on the characterization of V? I agree that V for Vendetta is probably irredeemably misogynist, but I feel like David Lloyd’s artwork, which makes V so terrifying, so evil-looking, basically a horror villain, goes some way toward undermining the idea that we’re supposed to root for him. Maybe not far enough.

I think, although you have quite a few valid points, your analysis fails because it assumes that, because V occupies the “hero”/protagonist slot in the book, he’s in the right. Like Suat’s Moore quote says, he gives you the romantically attractive anarchist hero, and then undermines it. I don’t know how anyone can read V’s torture and brainwashing of Evey without coming to the realisation that this guy is a terrifying fanatic who really isn’t any kind of improvement on the fascists (that’s the main thing I didn’t like about the film – it retained the torture/brainwashing sequence faithfully, but deprived it of any apparent purpose or meaning). All he brings (through his, I agree, implausibly ominpotence and omniscience) is chaos and violence. Can the violent imposition of one man’s will ever lead to the kind of anarchy, where everybody cooperates voluntarily, that V talks about?

I’m not an anarchist (I don’t think that kind of voluntary self-government is possible in anything but the smallest of self-contained communities) but I understand Moore is. I suspect he was working through some of the possible implications of anarchism, including some of the approaches to be avoided, when he wrote V. There’s always the possibility that I’ve misinterpreted the book completely and he’s right behind torture and brainwashing if it’s for the right cause – but I’d prefer to think otherwise.

A few years ago, Caro claimed that reading Noah’s negative take on Ghost World made her like Clowes more. Funny thing is that even though I agree with most of Isaac’s points, the piece actually makes me have fonder memories of V for Vendetta. I had no idea that so many people saw V as a despicable figure advocating a shitty system of anti-governance. So much more interesting than being the oppressed hero he’s been made out to be over the years.

I could change my mind once I actually reread the comic though…it might turn out like Swamp Thing.

Hello All,

I’m certainly open to other readings of the text. I’m not a big fan of there being a One True Reading of much of anything. That said, I guess what i would like to see is some actual textual evidence for these other readings of the book.I’m not sure it’s enough to say that V’s actions are clearly abhorrent. All that means is that we the reader find them abhorrent. As I cite in the above, Evey– the closest we have to a conscience in the book– explicitly endorses V’s torture of her as a justifiable mean to the end of her mental/spiritual/whatever freedom. V’s death and eventual “Viking Funeral” are treated heroically within the text as well. All anti-V sentiment in the text comes from the point of view of fascists… etc. and so forth.

I’m open to this reading, though. i think having more readings of something is a good thing.

I also find the idea that Moore changed his mind about his titular character and the series he was writing to be fascinating but I don’t really find much of a case in the text itself that he made the changes he’s talking about. Yes, V gets more complicated and less likeable in the second half. However, the ending of the book echoes the sentiments of the beginning, where the ever-expanding stack of bodies is simply a vehicle for the redemption of England and V is the martyr figure enacting our necessary sins in order to save us. You can practically hear the triumphant strings and brass and his subway car hurtles towards its explosive end.

On the other hand, the fascists are called Norsefire and V is given a Viking funeral. Maybe the soundtrack is Wagner.

Ha! Brilliant!

I’ve argued this out with Noah previously…and provided textual evidence, but I don’t think I have the energy to do it again. The main thing that indicates that the book is self-conscious about V’s actions as being terrible/horrible/negative is the parallels drawn between V and Adam Susan. There’s one episode wherein these parallels are made explicit, but when V takes over “Fate” and starts watching what everyone is doing in order to control it all (part of the evidence Isaac uses above for the book being boring), then, I think it’s pretty clear that V is not really much different from Susan. V tortures Evey “for her own good” and the “good of the many”–but, again, this is pretty clearly the same kind of thing that Norsefire does. (In fact, the experiments performed on the man from Room V that turn him into V are not much different from the “brainwashing” performed on Evey by V…He’s basically just paying it forward, to some degree). The fact that Evey elects not to become a killer, like V, is also something of an indictment of V’s methods (though, I admit, there is some intimation that violence is necessary in order to get to Evey’s “better place.”) I do think there are some ideological problems with the book (Evey forgiving V is something like Sally Jupiter “forgiving” the Comedian…but worse, since Sally never really does forgive Blake. It’s not only unlikely, but offensive, that they would become good buddies in the aftermath)). Nevertheless, the idea that the book promotes anarchy without admitting how anarchy may well end up like fascism just isn’t true. Obviously, there’s something to argue about here, because this is not the first time I’ve read a critique of V from this perspective…but it actually seems fairly obvious to me that the book is not promoting anarchy (or terrorism) as some kind of cure-all without horrific negative side effects. There is a fantasy of “fight the power” here, certainly…but it’s pretty obvious that in “fighting the power” one “becomes the power”–which is hardly an unproblematic solution. I think the book is self-conscious about this…Perhaps the reader is seduced into falling for V’s rhetoric…but I also think that the horrific torturing of Evey works (intentionally) to distance us from V. At that point, the reader is encouraged to hate/criticize/be disgusted by Evey’s torturers. We don’t know who they are yet, obviously, but once the “reveal” occurs, I don’t think we automatically say, “That’s ok then!” Rather, our hatred and disgust gets transferred to V himself. Sure…Evey eventually forgives him, but I don’t think we forget what he did…and in not forgetting, it’s no given we forgive.

I think the parallels with Susan don’t necessarily work the way you want them to; genre always draws parallels between the good guy and the bad guy. Thus all the bad guys who say, “you’re just like me”…but the point is always that they aren’t the same, because good and evil aren’t the same. Again, I think Moore has to fight harder against the genre to get the effects you’re talking about. He does that in Watchmen, but much much less so in V.

And…I mean, how hard would it have been to have someone in the book articulate a critique that stuck?

I haven’t read V in years, but I need to give it another look, I think. I do recall thinking that V was undermined, not only because he’s possibly crazy or because he does some terrible stuff, but also because his attacks are revealed to specifically target those responsible for his imprisonment and torture, making the whole thing a grand revenge scheme, with the side effect of toppling the fascist regime. Or maybe it’s vice versa, and he’s just getting the lucky benefit of vengeance along with a destruction of the evil overlords. Either way, I don’t think I ever thought it was a black and white story of good triumphing over evil.

I’m also interested in the misinterpreting of a work’s message, with a similar example being the movie Fight Club. That film seems to endorse anarchy, but then shows how that anarchy can be exploited and turned into its own version of fascism. But I think most people didn’t really take that message to heart, but just thought it was cool for guys to fight each other. I’m sure there are plenty of other examples of people missing the point; surely somebody just thinks Robocop is a cool robot policeman, right?

I’m surprised that no one mentioned Tony Weare’s drawings.

The problem the book has difficulty overcoming is the typical “good guy/bad guy” superhero problem, yes. V is the title character…wears a mask, has a secret identity…and thus seems to be a “superhero” (though, in its original form in Warrior, this would have been a little less clear…since it wasn’t a straight superhero magazine). Thus…V seems to be a “superhero” while the fascists are “villains.” At the same time, we get to know our fascists much better as human beings than in most superhero comics…and we get to know V himself much less (almost not at all). This helps offset the “we root for hero-guy!” element a bit.

Anyway…it’s not that “I want” it to work a certain way (as you imply–actually, you say it, not imply it)—it’s that I think it does work that way. Reading it as a pro-anarchy/pro-violence thing that we can then lob grenades at may be fun (in the spirit of hate week and all that), but I don’t think it actually describes the experience of reading the book. On the contrary, it feels like there is an effort to read the book as more simplistic than it actually is in order to make the critic feel/seem smarter. (“Alan Moore didn’t realize how much he was promoting terrorism and anarchy”–This kind of criticism only works if the book actually is promoting terrorism and anarchy—which it isn’t…Foolish Occupiers based on the crappy movie notwithstanding). Unlike most superhero books, the whole thing is not about black/white morality and cheering on the good guys in the sunshine while spitting on the bad guys shrouded in darkness. Elements of that kind of thing do crop up in the book…but it’s not the predominant feeling I get while reading it. If you want to call V a dry-run for Watchmen’s more ambiguous morality…that’s fine…but to call it a failure on these counts seems foolish.

The mere fact that these debates crop up on this site every year or so suggests that the book is not some completely simple-minded “us vs. them”

“good vs. bad” book. The ambiguity of its treatment of V (and others) is precisely what spawns the debate…

And…it’s not Susan who draws the parallel between himself and V (it’s either V himself or an external camera—can’t recall). Yes…if a villain says, “You’re just like me”–it’s a pretty good guess that the book has him say that in order to highlight the fact that the opponents are not the same (“No, Luthor, the difference is I’m Super-strong…and I’m a moral dude!”). If the “hero” says it, on the other hand,…I think that gives us pause (why is he saying it?). If the book simply draws parallels between the two and leaves it to us to draw conclusions…I find it hard to see how the conclusions we’re supposed to draw are opposite of the parallels drawn (why draw them then?)

All of this is to say that the book, to me, clearly intends to make V’s heroism ambiguous at best. At times, it succeeds in making us question V and his morality…At other times, he comes off more the hero… So…maybe the “genre tropes” overpower the attempt to subvert them at times… As in Watchmen, though, Moore trots out the genre tropes in order to interrogate them. Hard to see how to interrogate them at all if they are not on display, to some degree. And the same problems crop up in Watchmen, too (people see Rorschach as cool good-guy despite all the evidence to the contrary)…

We’ve hashed this out here several times before, so I’m going to try to avoid further hashification.

We haven’t talked as much about the misogyny issues, though. What do you think about that, Eric? I think Isaac’s points seem pretty on target….

———————-

eric b. says:

…The main thing that indicates that the book is self-conscious about V’s actions as being terrible/horrible/negative is the parallels drawn between V and Adam Susan…

…but I also think that the horrific torturing of Evey works (intentionally) to distance us from V. At that point, the reader is encouraged to hate/criticize/be disgusted by Evey’s torturers. We don’t know who they are yet, obviously, but once the “reveal” occurs, I don’t think we automatically say, “That’s ok then!”

———————-

Yes. Note how the movie, which shifted from V being for anarchy to the more palatable fighting for freedom, also had V expressing his agonized regret to Evey for the sexual humiliation he subjected her to. Whilst in the comic, he apologized not one whit. For anything he did.

One of the countless ways in which the comic’s V is a chillingly ambivalent figure. (Didn’t the doctors “treating” him in that concentration camp consider they’d driven him insane?)

———————-

…the book, to me, clearly intends to make V’s heroism ambiguous at best. At times, it succeeds in making us question V and his morality…At other times, he comes off more the hero… So…maybe the “genre tropes” overpower the attempt to subvert them at times…

———————-

Indeed; and doesn’t that overpowering remind of how Rorschach, whom Moore more clearly intended to be a creepy figure, nonetheless ended up admired by many?

———————-

steven samuels says:

…that rape and torture sequence you described was quite troubling, needless to say.

———————

So, a “body cavity search” — something routinely given prisoners, male and female — is now rape? Sure, it’s a disgustingly humiliating procedure, but if the term gets splashed around so freely, doesn’t that “devalue the currency” of actual rape?

Ah, but the More PC-Than-Thou crowd are into pushing this image of Moore — who’s created as richly human, complex, sympathetically-portrayed women characters as anyone*; whose progressive credentials are impeccable — as some slavering pro-rape creep. Because to depict violence against women is to be in favor of violence against women. (Hey, and Agatha Christie must love murder! Look at all the people that get killed in her books!)

If anyone deserves that condemnation, it’s Milo Manara, whose rape scenes — instead of being appalling, brutal, revolting, as Moore makes his rape/attempted rape scenes — are slimily exploitative, the women prettily oohing and aahing, obviously enjoying themselves.

But, leftists far prefer to endlessly bicker and fight among themselves, attack those who are not “ideologically pure,” rather than unite against the common enemy.

*Oh, but he’s dared in the comic to feature a nasty, villainous woman, who actually uses her sexuality to manipulate her hapless hubby. Since nothing like that ever happens in real life, here’s further proof of how much Moore hates women!

Actually, I do comment on it a bit above (first comment?)… Maybe I’ll have more to say about it…but I have to go teach a class. (Yes at 7:00PM–long night)

Oh; one more thing. Of course you have to use the tropes to question them. But at the same time, it seems like if you are trying to use them against themselves, you can succeed…or you can fail.

I think Alan Moore is somebody who is both powerfully attracted to, and powerfully repulsed by, pulp tropes around violence, sex, and power. The balance of that attraction and that repulsion varies from work to work, and is what gives his books a lot of their interest. But…he doesn’t always get it right, and especially in V, I think his sympathy for anarchy and his sympathy for powerful pulp heroes gets him in serious trouble.

For example; your reading, Eric, depends on the possibility that V is insane or evil. But the book constantly presents him as not only good, but really beyond our ability to judge. The crazy pattern on the floor that ends up being carefully constructed, for example; he’s supposed to be smarter than we are, and if that’s the case, how exactly can we deem him insane? Similarly, that scene where the woman doctor asks him to take off his mask — the implication is that his features are unearthly, and not in a bad way. And she, of course, also forgives him for what he does, just like Evey. And he’s immaculately cultured…and, most of all, he removes himself in the end, showing his own nobility and the ultimate purity of his goals.

I don’t deny that Moore is trying to think about the parallels between anarchy and fascism. But his commitment to his good guy/bad guy genre tropes — the way, for example, that his bad guys are made sexual deviants while V is pure and even virginal in his relations with Evey (except for purposes of education I guess) work against the point he’s trying to make, and ultimately undermine him rather than the tropes.

Oh…and I’m never really convinced by the “it sparks discussion so it must be complex” argument. Alan Moore is very accomplished, and V’s an important work in his career. That’s reason enough for folks to talk about it, it seems like…and why can’t differing views be evidence of incoherence on the part of the work, rather than on the part of the critics?

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

…the crazy pattern on the floor that ends up being carefully constructed, for example; he’s supposed to be smarter than we are, and if that’s the case, how exactly can we deem him insane?

————————-

So, are all crazy people automatically stupider than we are? What about the “savant syndrome” types? Could not V be seen as an utterly cunning, brilliantly manipulative psychopath? (In the movie version I had in my mind when first reading the serialized comics, I always imagined Anthony Hopkins as supplying V’s voice.)

————————-

…and, most of all, he removes himself in the end, showing his own nobility and the ultimate purity of his goals.

————————–

Of all things, V reminds me of a bit in a Mickey Spillane book where his violent hero — tommy-gunning a bunch of Chinese Reds — describes himself as the evil that destroys a greater evil, that the meek may inherit the earth.

V definitely sees himself and his actions as, at best, a “necessary evil.”

—————————

…why can’t differing views be evidence of incoherence on the part of the work, rather than on the part of the critics?

—————————

Sure, they could be; and, they also can be (as in the case of 40% of the American people believing the Earth is less than 10,000 years old) evidence that some people are incapable of seeing the most blazingly obvious truths, no matter how much evidence in their favor is presented.

————————–

Ng Suat Tong says:

I think the idea here is that Guy Fawkes’ reputation is complicated – anarchistic terrorist, Catholic villain, source of religious hatred, popular hero, ritualistic effigy disconnected from religious content etc. Don’t think the reaction was meant to be (exclusively) Guy Fawkes – cool modern day hero.

————————–

The actual Guy Fawkes wanted to annihilate the at least somewhat-democratic Parliament, and bring in a burn-the-infidels Catholic dictatorship. In England, he’s certainly been viewed as a villainous figure, a boogeyman yearly burnt in effigy, kids going around asking for money to do so: “Penny for the Guy, sir?”

Thus this, rather than proving that Moore was an idiot for having V wear a Guy Fawkes mask, further clearly shows how ambiguous the character was intended to be.

Just slid from the shelves my trade paperback copy of “V for Vendetta’ for rereading: more “hating the hate” to follow!

Everyone else is hashing out the merits of Isaac’s case, but I want to add: this was really great fun to read. My favourite piece of the hateschrift so far.

My own reading is that V becomes somewhat more ambiguous over the course of the book, but is nowhere near as clearly demented/despicable as Rorschach. Evey’s forgiveness and acceptance of her brutalisation is morally repulsive — V is the ultimate abusive boyfriend. But I still enjoy the book, obnoxious ideology and all.

Anyway, Isaac, you’re neglecting the key element of suspense in the book: what v-word will cap the next chapter? Verbosity? Verificationism? Vulvodynia?

Mike…having someone penetrate you against your will seems like a decent definition of rape. Certainly it qualifies as sexual assault.

I think Moore often handles sexual assault thoughtfully, and I think he is very much a feminist and tries to present, and often succeeds in presenting, sympathetic and nuanced female characters in his work. But if Mark Twain lost the occasional fall with racism (as Ralph Ellison correctly says that he did), then I don’t think it’s crazy to suggest that Moore lost the occasional fall with sexism.

Oh, and as I’ve said before, the morality of cozies is definitely problematic.

I think Milo Manera is going to come up later in the roundtable, FWIW.

“But the book constantly presents him as not only good, but really beyond our ability to judge.”

I think that’s a willful misreading of the book. Other characters are *constantly* judging him, and we’re presented with a series of pretty simple Morality 101 ‘does the end justify the means?’ situations. The movie fucks it up big time by making him far more romantic and caring. The comic book version is horrible. He does abuse Evey. He does brutalise her. I don’t think you’re meant to see her transformation as ‘the truth’, and after it she’s clearly got some form of dissociative mental issue.

The question as to whether this is a clash of ideologies or an insane man taking revenge is also constantly there, being asked.

The comic sets it up as a bunch of mid-level, ordinary bureaucrats who have come to use state power to maintain order in the face of chaos, subject to lots of normal people problems like money worries and careerism … versus a man in a mask who kills without any compunction. It’s the fascists who hesitate before firing, the ‘hero’ who kills people just because it’s easier than walking round them.

Ultimately, V comes to realise that he is not the one to build what comes next, he can only tear down what there is. That ‘imposing anarchy’ is as totalitarian as any other imposed system.

Seeing it as the relentless progression of one narrative, again, is reading against the text. The book retells events from different points of view, it has people reconstructing events after the fact, imposing their own meanings on them.

V for Vendetta isn’t perfect, it’s very clearly made up as it goes along, it starts out as a very obvious ripoff of Theatre of Blood, it makes British Eighties Leftie Error #1 which is to see Thatcher as somehow exactly equivalent to the BNP, the Guy Fawkes-was-a-hero thing is Tea Party levels of nuts. But if you think V’s ‘the hero’, you’re missing the context, which is that with a handful of exceptions British comics – most British heroic narratives – have always been about anti-heroes, not paragons of virtue who we’re meant to believe in. From the real, British, Dennis the Menace to Judge Dredd, we Brits are weaned on *bastards* in our comics. V’s a bastard.

“And…it’s not Susan who draws the parallel between himself and V (it’s either V himself or an external camera—can’t recall).”

I’m not clear what you mean by this Eric, but Moore uses transitional devices all the time linking two things in different spaces and time, its one of his most basic formal devices.

In his writing for comics essays he writes “The important thing is that the reader should not wake up until you want them to, and the transitions between scenes are the weak points in the spell that you are attempting to cast over them. One way or another, as a writer, you’ll have to come up with your own repertoire of tricks and devices with which to bridge the credibility gap that a change in scene represents, borrowing some devices from other writers and hopefully coming up with a few of your own.”

I’m not sure what scene you are referring to, but a mere transitional device wouldn’t be saying much. If this camera thing is something more than that you haven’t made your case.

And Matthew, I think V is killing everyone who knows his secret identity so he can “be a symbol” so his motivation isn’t base revenge. Its been years since I read the book, though.

Think of the narrative in terms of sublation.

Norsefire’s counterpoint is V.

V’s counterpoint is Evey.

Evey’s counterpoint is Dominic.

Dominic–and what he represents–is the hope for the future.

As far as Moore’s political message is concerned, Dominic is by far the most important character in the book.

That’s all for now.

Some less than optimal usage above. Exchange “‘s counterpoint is” to “gives way to,” and it may be clearer.

Pingback: Evening Links | Thought at the Meridian

Pingback: Critical Linking: September 18th, 2012 | BOOK RIOT

——————-

Jones, one of the Jones boys says:

…My own reading is that V becomes somewhat more ambiguous over the course of the book, but is nowhere near as clearly demented/despicable as Rorschach.

——————-

I’m halfway through rereading the trade paperback, and Rorschach — poor dining habits, creepy monotone voice and all — is a teddy bear compared to V.

——————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Mike…having someone penetrate you against your will seems like a decent definition of rape. Certainly it qualifies as sexual assault.

——————–

So, everybody who gets a “body cavity search” by the police or looking-for-drugs DEA officers can sue or have them arrested for “sexual assault”? Intent is everything here; those examinations are done to search for hidden weapons/contraband, rather than sexual pleasure (though of course, some nasty types may derive jollies from the act), therefore are legally excusable.

——————–

I think Milo Manara is going to come up later in the roundtable, FWIW.

———————

Now, there’s someone who deserves every bit of mud flung his way! God, how I loathe him…

Rereading “V for Vendetta,” I was startled (it’d been a while since my last reading, and the ol’ memory’s not what it used to be) how blatantly, from the very first, V is clearly made to be…well, “morally ambiguous” is the understatement of the century.

(For now, I’ll leave off mentioning the many bits in the book which make nonsense of the “Moore the misogynist” malarkey, and just deal with that which shows V was hardly intended as a simply heroic figure.)

Dunno how many here have the “pamphlet” issues to look at. I’ll give page numbers from the trade paperback, but mention “chapters” to indicate which individual issue the examples noted are to be found in.

Chapter 1 – The Villain

In the very first page, our first glimpse of V is as he advances toward his make-up table in the Shadow Gallery. While more innocuous ones will later be depicted, what are the movie posters we see surrounding the dress-up table? Which surely Moore specified in his script? “White Heat,” where Cagney plays a psychotic killer who later self-immolates explosively (recall how V’s remains were sent off). There’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” not so related to V but more to the detective who’ll track him down ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Murders_in_the_Rue_Morgue ), and “Son of Frankenstein”; V clearly a Frankenstein’s monster figure.

In page 13, asked by Evey who he is, V responds, “I’m the bogeyman. The villain…”

Chapter 3 – Victims

In page 24, Finch, the decent detective who has repeatedly told the Leader he doesn’t believe in the fascist system, but does his work to help England, describes V’s killing of several security agents: “Whatever their faults, those were two human beings…and he slaughtered them like cattle!”

Page 28: Evey recalls how after the war, “There were riots, and people with guns. … Everybody was waiting for the government to do something… But there wasn’t any government any more. Just lots of little gangs, all trying to take over…” Um, doesn’t that sound like the situation that would result after V overthrows the current regime?

Chapter 4 – Vaudeville

In page 31, V doffs his Guy Fawkes mask for that of Mr. Punch; a murderous, terrifying, damn-near-supernaturally powerful (he beats the Devil!), antiheroic figure. As http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punch_and_Judy points out, “He is a manifestation of the Lord of Misrule and Trickster figures of deep-rooted mythologies.” The “skeletal outline” of Punch tales “…typically involve Punch behaving outrageously, struggling with his wife Judy and the Baby, and then triumphing in a series of encounters with the forces of law and order (and often the supernatural), interspersed with jokes and songs…It is rare for Punch to hit his baby these days, but he may well sit on it in a failed attempt to “babysit”, or drop it, or even let it go through a sausage machine…” This Punch mask will later feature prominently in a terrifying nightmare of Evey’s.

Chapter 6 – The Vision

Pages 43-44: Evey asks V about the prominently-displayed motto in the Shadow Gallery: “Vi veri veniversum vivus vici.” Then she says in return for what he’s done for her, she ought to help him: “I mean that’s the deal, isn’t it?…I want to do something [to help him]…Can’t we make a deal?” V accepts. When Evey asks him who originally said that VVVVV quote, he says, “A German gentleman named Dr. John Faust. He made a deal, too.”

Page 54: V greets the “pedo” bishop: “Please allow me to introduce myself…I’m a man of wealth…and taste.” Doffing his hat, horns are revealed.

Chapter 9 – Violence

Page 64: Evey is appalled V killed the bishop: “It’s wrong, V…You involved me…killing’s wrong…isn’t it?” He cooly replies, “…As for me involving you, I seem to remember that you were the one anxious to make a deal.” Evey chokes, “I didn’t know you were going to…Oh, Christ, V…” before running from the room. Unruffled, V goes back to his book.

Page 72: Finch (who is sympathetically depicted as a good man trying to do the best he can — V, in his “Vicious Cabaret” lyrics in page 90, describes him as “a policeman with an honest soul” — even if his employer…leaves something to be desired) discovers that over a period of years, V has been killing everyone involved in running the Larkhill “Resettlement” Camp: “Oh God. All those people. That’s monstrous. That’s pure bloody evil.”

Page 75: Delia Surridge, a doctor who’d worked at Larkhill and grown to feel horrible guilt over what she’d done, try to make amends (“I’ve seen her treating little kids…” Finch recalls), awakes to find V by her bed. “…you are going to kill me.” V holds up a hypodermic: “I killed you ten minutes ago. While you were asleep.” (Brrr! That’s one of the most chilling lines I’ve ever read…)

Chapter 11 – The Vortex

Page 81: In her diaries while working at Larkhill, Delia Surridge — a trained doctor, remember; her diagnosis not to be lightly dismissed — describes how the man in room V has reacted to their medical experimentation: “He’s quite insane. Batch 5 seems to have brought on some kind of psychotic breakdown.”

Page 84: Finch (synopsizing V’s activities) “He abducted Lewis Prothero,…who had chosen him to receive batch 5, the preparation that had destroyed his mind.”

The most brutal of V’s actions are yet to come…”To Be Continued!”

I wonder if our different readings come from the comics we trained on. If you grew up reading superhero comics, which used to present their heroes as unambiguous moral ideals, you might see V for Vendetta in that light and look for ideals in its characters. I was trained on 2000AD, where morally ambiguous heroes are the norm, and morally monstrous heroes not uncommon, so I look for and expect the undermining of ideals. I’ve never read V as a superhero – he’s far more in the tradition of Judge Dredd, which is to take a character type – the violent cop who does what’s necessary in Dredd’s case, the romantic lone freedom fighter in V’s – and test it by coming at it from an unexpected angle and taking it to extremes, so you see it in a different light. An awful lot of Moore’s work works that way.

On the gender politics aspects of the critique. I dislike this kind of ideological criticism, where fiction is expected to provide role models of self-actualised women without character flaws, and anything else is considered “misogynist”. To my mind, the depiction of an abused woman who has grown dependent on her abuser, or of an abusive woman who uses men to gain power and status for herself are far from misogynist, any more than depicting Peter Creedy as an abuser and Conrad Heyer as abused and dependent is misandrist. It’s just depicting characters. I do think there are problematic aspects to Moore’s gender politics – he has an occasional tendency to wallow in male sexual violence against women to show off his feminist credentials – but he doesn’t do that much in V. He does give Delia Sturridge – a concentration camp doctor who experimented on people – a moral redemption of sorts, which he doesn’t give any of the men involved, which strikes me as a bit “sugar and spice”.

” I dislike this kind of ideological criticism, where fiction is expected to provide role models of self-actualised women without character flaws, and anything else is considered “misogynist”.”

You have set your straw man righteously on fire…but Isaac doesn’t say anything like that.

I think the suggestion that different readings come out of different contexts (particularly superheroes vs. 2000 AD) is quite interesting though.

Remember that V was originally written for an exclusively British audience. Moore has himself said that he was adressing a familiar trope of British comics and popular culture, the villain as protagonist: the Spider, the Claw, going all the way back to ballads of highwaymen like Dick turpin or indeed to Robin Hood…

I didn’t see V as a superhero. In fact, after reading it several years ago and going to the Wikipedia page, I was surprised that Superhero was one of the genres. Also, I have to agree with Mike. I didn’t see V as a sympathetic figure, especially after the torture part. That part brings to mind cult brainwashing.

I loved this piece. I have plenty of affection for Swamp Thing and Watchmen, but V for Vendetta blows.

A pompous homicidal wank aunting someone with fake homophobic murder, I, just…. if there’s some secret “too clever by half” narrative it’s a wry right-wing parody of empty leftist rhetoric. And there’s not much wry right-wing parody nowadays (of the intentional and non-self-directed variety), so that would be novel. But that’s not what’s going on.

Although I feel sort of like the Moore of your critique, Isaac, since my favorite quote of yours (“Moore gets to have it both ways, making a case that a radical anarchist state would be a really great thing without ever having to imagine for the reader what that world would look like. “) expresses similar sentiments to my own: http://gayutopia.blogspot.com/2007/12/bert-stabler-glory-and-hole.html But yes, thank you, I agree with your criteria and your conclusion. Thank you.

I meant to say “taunting” not “aunting,” but I stand by the two “thank yous.”

Bert, quoting Isaac:

““Moore gets to have it both ways, making a case that a radical anarchist state would be a really great thing without ever having to imagine for the reader what that world would look like.“

Well, but does he have to spell things out? In V, there’s a c-story about murderous gangs poised to sow misery and chaos as soon as the Fascist fist unclenches.

(This has an actual historic parallel: the Italian Fascists’ near elimination of the Mafia from Sicily was totally reversed after the Allied invasion.)

Moore built ideological ambiguity into V from the start.

Pingback: Erotica's Newest Millionaire; The Year of the Sock Puppet | News 47News 47

In Watchmen, yes, the ambiguity is there. Even if his moral law and his sadism converge in Veidt, he’s hardly off the hook, either diegetically or meta-narratively. But I gotta say that in V it feels like having your humanism and eating it too.

———————

Patrick Brown says:

I wonder if our different readings come from the comics we trained on. If you grew up reading superhero comics, which used to present their heroes as unambiguous moral ideals, you might see V for Vendetta in that light and look for ideals in its characters. I was trained on 2000AD, where morally ambiguous heroes are the norm, and morally monstrous heroes not uncommon, so I look for and expect the undermining of ideals. I’ve never read V as a superhero – he’s far more in the tradition of Judge Dredd, which is to take a character type – the violent cop who does what’s necessary in Dredd’s case, the romantic lone freedom fighter in V’s – and test it by coming at it from an unexpected angle and taking it to extremes, so you see it in a different light. An awful lot of Moore’s work works that way.

———————-

I didn’t think of the “British comics factor” there…an outstanding point! Richly added to by Jemima Cole’s “From the real, British, Dennis the Menace to Judge Dredd, we Brits are weaned on ‘bastards’ in our comics. V’s a bastard.”

———————-

On the gender politics aspects of the critique. I dislike this kind of ideological criticism, where fiction is expected to provide role models of self-actualised women without character flaws, and anything else is considered “misogynist”. To my mind, the depiction of an abused woman who has grown dependent on her abuser, or of an abusive woman who uses men to gain power and status for herself are far from misogynist, any more than depicting Peter Creedy as an abuser and Conrad Heyer as abused and dependent is misandrist. It’s just depicting characters.

————————

Realistically complex characters. But then in radical-feminist-land, when a woman says “no,” it means utterly, irrevocably “no,” not — as one woman psychologist mentioned in her book — a false denial, because she doesn’t want to be thought of as “easy.” (Needless to say though, a “no” should still be taken at face value.) And in radical-feminist-land, if a husband slaps a woman once, she’ll instantly lose all love for him, walk out with the kids and start a fine new life on her own. Never mind that — as detailed in “Women Who Love Too Much” — some unfortunates believe that getting beaten on a regular basis is part of “love” (as taught by the examples of Mummy and Daddy), and they can only love someone who is abusive; or manage to still love despite the abuse. “He’s always so sorry afterward…”

—————————-

I do think there are problematic aspects to Moore’s gender politics – he has an occasional tendency to wallow in male sexual violence against women to show off his feminist credentials…

—————————

An excellent point; consider the “Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” series of books, whose left-wing, feminist author rubbed readers’ faces into heinous violence against women, that we should be reminded how awful it is.

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

”I dislike this kind of ideological criticism, where fiction is expected to provide role models of self-actualised women without character flaws, and anything else is considered “misogynist”.”

You have set your straw man righteously on fire…but Isaac doesn’t say anything like that.

——————————-

Then how come the countless accusations of “misogyny” (how lightly that bit of character assassination is flung! But then, if you’re on the side of the angels, everyone else is a devil) by him and others, here and in “Watchmen”-related HU threads? Consider the countless words of outrage about how dare Sally Jupiter feel any affection whatsoever for the Comedian (never mind that she’s shown as not very bright and rather weak, except when it comes to protecting her daughter), and how “misogynist” all that is.

And…

—————————–

isaac says:

…we have Helen Heyer. Helen becomes a regular presense in the third act of the book, as the (oddly fragile given that it’s supposed to be frighteningly all-powerful) society crumbles. The wife of a high-ranking fascist, Helen tries to maneuver her husband into the role of Leader by sexually manipulating his colleagues. She also refuses him sex. Helen is a classic misogynist caricature, simultaneously frigid and a whore, using her body to get ahead.

——————————

Yes, to depict — as part of the exceedingly wide and varied cast of characters in the book — a type that actually exists, and is hardly freakishly rare, is a “misogynist caricature.” Because only “self-actualised women without character flaws” are acceptable to the PC crowd.

—————————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Oh, and as I’ve said before, the morality of cozies is definitely problematic.

——————————

Oh? Like in, how dare Miss Marple get that nice murderer arrested? (Certainly many victims in “cozy” mysteries deserved to get killed; but in order to create a wide pool of suspects, it helps if the “body in the library” was a mean and nasty type, who’d make enemies wherever they went.)

——————————-

AB says:

…In V, there’s a c-story about murderous gangs poised to sow misery and chaos as soon as the Fascist fist unclenches.

(This has an actual historic parallel: the Italian Fascists’ near elimination of the Mafia from Sicily was totally reversed after the Allied invasion.)

——————————

On the other side, FDR’s guys actually made a deal with the American Mafia, to keep Nazi spies and saboteurs off the docks…

Yep, with Vito Genovese and Lucky Luciano.

My dad actually had lunch with Luciano once.

“Yes, to depict — as part of the exceedingly wide and varied cast of characters in the book — a type that actually exists, and is hardly freakishly rare, is a “misogynist caricature.” Because only “self-actualised women without character flaws” are acceptable to the PC crowd.”

That’s a classic misogynist excuse. Rappers use it all the time when confronted about misogyny in their lyrics. “Well women like that really exist in the hood!” It’s bullshit rationalizing for them, and it’s bullshit rationalizing when you do it too. You’re better than that, Mike.

Is that prominent ‘V’ in Veidt ‘s logo a coincidence? I doubt it!

On a different tangent, I can’t help but notice something. 1984 and Brazil both end tragically whereas V for Vendetta sees the realization of V’s plan (without us seeing the conclusion, as you point out).

While I love 1984 and Brazil (and the Russian antecedent, We) of course their conclusions are depressing and I would much rather see the authoritarian government deposed. The question arises how can one write a story that doesn’t devolve into “agree with me or get blown up” when confronted by an authoritarian government?

What I’m saying is I can’t help but think that Lowry or Winston might have succeeded had they resorted to violence.

This isn’t to say a peaceful revolution in reality is impossible, because the Velvet Revolution among others demonstrated that it is possible. The question is in making a fictional story interesting for its duration when the main character is essentially powerless in the face of authoritarian power yet achieves victory. (I should note I am attempting to do so, and it has proven challenging, as you can see with my thoughts here.)

I’d highly recommend William Taubman’s biography of Khruschev. Among other things, it chronicles how Russia peacefully moved from a deranged homicidal totalitarian regime to a garden variety, still unpleasant but by no means as bad as it used to be, authoritarian state.

I think genre and narrative conventions can really limit the imagination when it comes to this sort of thing. There is no absolute totalitarian state, and the options for overturning a bad government are really pretty varied — from violence, to serious organized peaceful resistance, to rejiggering of power. And the options aren’t just freedom and totalitarianism — generally, in most states (including ours) you end up somewhere in the middle.

Along those lines…it’s not an accident that Stalin, the monster, remains famous, whereas Khruschev, an incredibly brave and heroic figure despite massive flaws, is basically ignored. We’ve got a strong narrative bias towards absolutes.

Noah, have you been paying attention to Syria? To Libya?

Tried non-violent, got massacred. Time for violence now.

Fascinating discussion. I disagree with the main thrust of Isaac’s critique for reasons that the other British commentators here have given. (I’ve been discussing the anti-heroes of 2000AD with Douglas Wolk recently so the topic is pretty fresh in my mind: http://dreddreviews.blogspot.com/2012/09/brothers-of-blood.html)

But as is clear from that interview with Moore, helpfully cited by Ng Suat Tong, V started out as one thing and became something else. It began as a super-stylish pulpy romp, appearing in six-page monthly installments in STARK black and white (without lines around the word balloons, even). It was 1982, Thatcher was still in her FIRST term, and the innovations of the work more than outweighed its derivative or implausible elements. It’s quite hard to recapture, now, the thrill of reading V, then; but I recall feeling the excitement of discovery with each episode, knowing that Moore and Lloyd were pushing at the boundaries of what could be done in British comics, before my very eyes.

But it ended very differently, almost eight years later. By this time it had become the “other” graphic novel by “the creator of Watchmen,” freighted with post-Watchmen levels of expectation, and repackaged according to the normative tastes of a different national audience: a colorized monthly of twenty-or-so pages per installment.

For a project that turns out to be roughly the page equivalent of a year-long 12 part mini-series, eight years is a ridiculously long time from inception to execution, and the creative techniques and attitudes of the writer had obviously transformed considerably over those years.

IMO then, the flaws in V are largely a function of the exigencies of the popular serial form, and the particularly vexed circumstances of V’s significantly interrupted publication history. Depending on one’s perspective, the result is (at best) a damaged masterwork – and (at worst), an occasionally incoherent mess. Personally, I’ve always found the last quarter of the book disappointing (Isaac didn’t mention Finch’s “enlightenment through acid” sequence – surely one of the lazier moments in all of Moore’s canon) and suspect that Moore was simply feeling less inspired by V after the imposition of a five-year publishing hiatus, over the course of which he had developed other interests.

Of course, that is just speculation. But it’s a fact that V was an interrupted project, and I think very few such creative projects could emerge undamaged from such a history. The result, I think, is a book that is really two quite different books spliced together and spray-painted with color for re-sale on the American market in a way that can make it hard to see the join. But that fundamental incoherence is there, and it gives Isaac’s critique some purchase.

Moore’s Marvelman/Miracleman (the first episode of which appeared alongside the first episode of V in Warrior #1 – yes, it was an exciting time to be reading British comics) is similarly hamstrung. It is, IMO, both better than V, and worse – better in that Moore’s original conception survives the long, strange, trip that it took to bring out the damn thing, but worse in that he had no consistent artistic collaborator, no David Lloyd to help create the illusion of seamlessness through the nightmarish transitions between publishers and markets. The early six-page installments featured some lovely black and white art by Garry Leach, filled with fabulous use of zipatone, and which adapted even less well to standard US color-monthly format.

Great discussion all round, though.

Alex, I’ve been following Libya and Syria more or less. I don’t know how well violence has ultimately worked in either case. In Libya, American intervention has apparently led to an extremely unstable government and a huge potential mess. In Syria, it sounds like there are atrocities on both sides (though the Assad regime is worse) and lots and lots of people dead. The whole thing seems to suggest more that some problems are really intransigent than that violence leads to righteousness and peace, as far as I can tell.

I gave Ben’s comments their own post here.

One thing I will agree on is Helen Heyer…she is a misogynist stereotype. I do think though that there is actually some clever feminism in V. The fascists in power are an all-male boys club (I don’t think that’s an accident)…and their violent mirror in V, also male. If there’s hope it’s in Evey (a woman). One could argue that Helen is forced into using her sexuality to gain power since she is denied any kind of power in the patriarchal society which surrounds her (just as Rosemary Almond turns to stripping as her only option in a society which defines women as either whore or virgin/wife. She loses her role as wife and is forced into the alternative). In Rosemary’s case, I do think it is portrayed as something she is forced into by fascist/patriarchal society (the two are linked…) In Helen’s case though she really does just come across as stereotypical dragon lady with no depth… so…there’s a hit by Isaac. I’ll admit it.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says: