Reading Joe Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza, I kept coming back to the same question. Namely — journalism as comics? Why? Sacco’s project — interviewing individuals in the Gaza Strip who were witnesses to two different Israeli massacres in 1956 — could easily have been presented as an agitprop book or as an agitprop documentary film. His methodology — the careful documenting of atrocities, the humanizing of the enemy, the nuanced by firm advocacy for the powerless — are all familiar tropes and tactics of left-wing investigative print and film journalism. Given that the content is familiar, what exactly does the comics form add? Why bother with it?

It’s a question that’s likely to make comics fans bristle. After all, to turn the question around, why should comics have to justify itself while other forms do not? Shouldn’t the success of the endeavor be more important than the medium?

Perhaps. And yet the question persists…in part because when you’re doing Joe Sacco’s brand of journalistic advocacy, journalism in prose and journalism in video have some major, easily apparent advantages over journalism in comics. Prose is unobtrusive and easily distributed; a Human Rights Watch report, for example, can provide facts and talking points with minimal fuss, and can also be readily quoted, linked, and copied, spreading a targeted, clear, footnoted message to as broad a range of people as possible. Film, on the other hand, can provide a sense of presence and urgency which is difficult to duplicate, allowing witnesses to speak in their own words with an authority and resonance that is very difficult to duplicate.

The advantage of prose or of film can perhaps be summed up as “authenticity.” Journalism’s goal is to show truth, and so spur to action. Prose and film are, for historical and formal reasons, often seen as at least potentially transparent windows on truth. Comics, on the other hand, foregrounds its artifice; as Sacco mentions in his introduction, everything you see on the page is rendered by his hand. And this is, incidentally, why Sacco is seen as an artist, rather than just as a reporter. Certainly, nobody that I’m aware of has ever referred to an HRW report as the work of a mature artist who has found his own style and voice, which is what friend-of-the-blog Jared Gardner called Sacco in his review of Footnotes in Gaza.

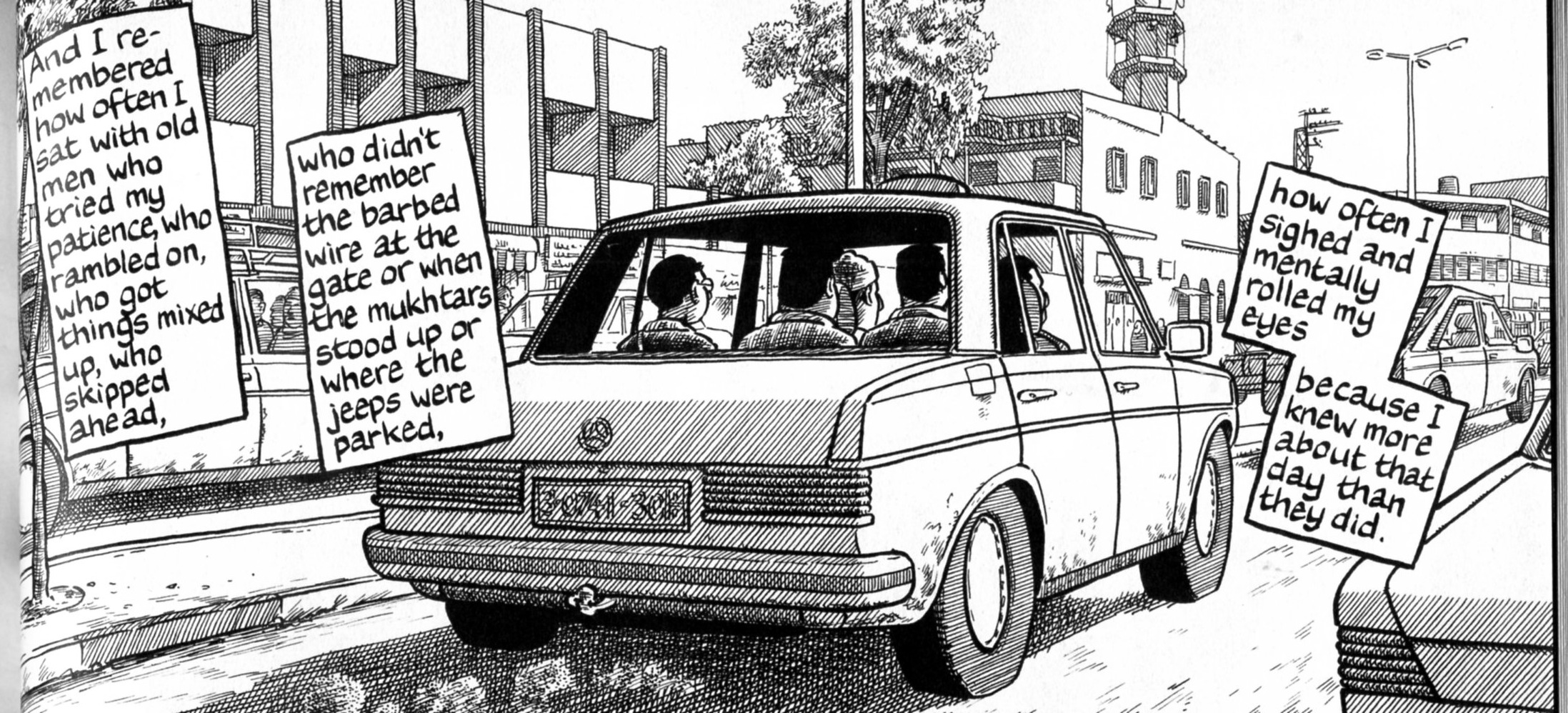

One upshot of making journalism comics, then, is to make journalism art, and to make the journalist an artist. The downside of this is that you then end up in a situation where the genius and sensitivity and angst of the journalist ends up pushing to the side the suffering and injustice which is the journalism’s putative subject. Sacco is certainly aware of this danger, and makes moves to undercut it, or problematize it, as on this second-to-last-page of the graphic novel.

However, I don’t think these gestures are ultimately successful. In this case, for example, indicting himself for insensitivity and hubris ends up validating his sensitivity and honesty, and also makes the book as a whole about his psychodrama and growth — about his experiences in Gaza, rather than about the experiences of those who are stuck in the place on a more permanent basis. In this context, contrition for selfishness still ends up as a way for the self to take up more space. The comics form has allowed/impelled Sacco the journalist to become Sacco the genius.

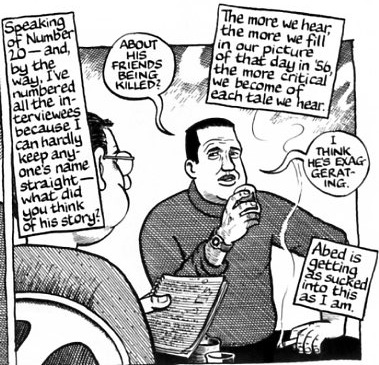

But while the artifice of comics journalism has its downsides, it has some advantages as well. Most notably, Sacco’s narrative is in no small part about the uncertainty of memory and of history. Comics, precisely because of its unfamiliarity as journalism, is less transparent; it demonstrates, almost reflexively, that journalism is not “truth,” but an effort to reconstruct truth.

Again, precisely because comics is a less familiar form for journalism than film or prose, it ends up emphasizing its own artificiality. Everything you see in Footnotes in Gaza is created and represented by Joe Sacco. His account always has a built in asterix. What he shows you is not what happened, but a collage stitched out of the words and memories of his interviewees and the fabric of his own visual imagination.

Sacco uses comics, then, to emphasize subjectivity. But…do you need to use comics to do that? Writers have been exploring the wavering, difficult nature of truth and of history for hundreds of years in prose, surely. Joseph Conrad’s narratives within narratives within narratives, or Paul Celan’s bleak koans hovering on the edge of comprehensibility, to cite just two examples, seem like more challenging and more thoroughgoing efforts to wrestle with the intersections of meaning, subjectivity, and historical trauma. For that matter, those Human Rights Watch reports I mentioned are usually pretty good about discussing the difficulty of gathering evidence and the conflicting testimony of witnesses. Do we really need the comics form to tell us that human memory isn’t perfect?

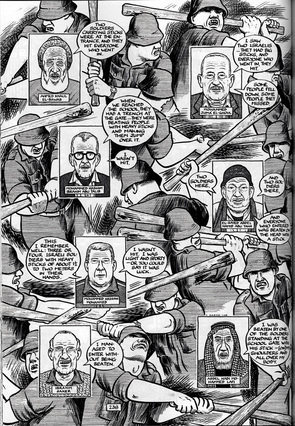

Indeed, the use of comics seems in some ways like a epistemological shortcut. Subjectivity can be linked to, or summarized as, the comics form, which is shown as obscuring the objective truth of reason and trauma. Comics may serve to call reportage into question…but it also, at the same time, validates or stabilizes the reportage. Thus, in that page above, the images of the Israeli’s swinging clubs are imaginative, or unverified…and their unverifiedness contrasts, or highlights, the more vouched veracity of the portraits, which are (at least probably) photoreferenced. And the referenced images, in turn, highlight the even greater veracity of the words, taken down from (presumably taped) interviews. Thus, while the comics form may initially appear to highlight subjectivity, it could instead be said to create a fairly clear hierarchy of representation, in which Sacco’s deployment of his research materials and his illustration signals the reader what is “truth” and what is less so.

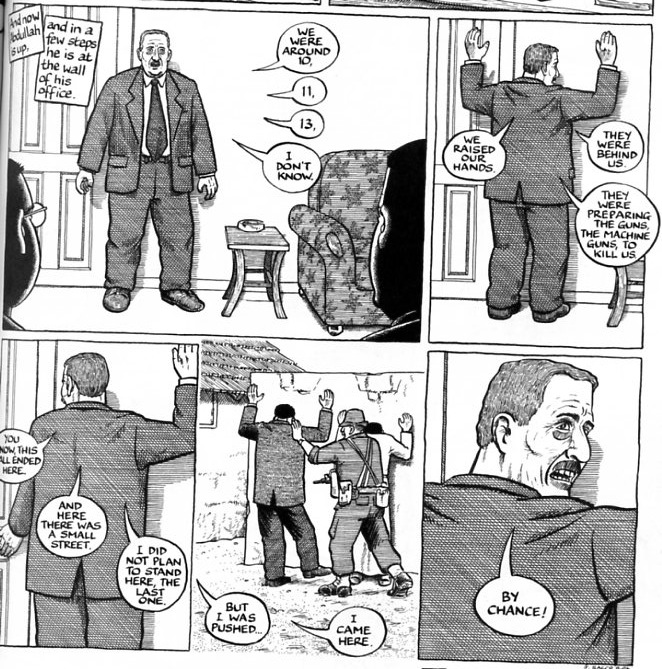

This isn’t necessarily a weakness. You could argue that comics’ strength as journalism lies not in its artificiality per se, but rather in the ease with which it can evoke differing degrees of artifice; in the resources it has available for signaling truth or falsehood, or different levels of both. For example, one of the most interesting aspects of Sacco’s book is the way that he shifts back and forth between the 1956 atrocities and the ongoing violence on the West Bank. For comics, where still images evoke time, it is relatively easy to make two times equally physical and equally present.

Comics’ ability to show bodies discontinuous in time is used here to show trauma across decades; the self from the past is as real as the self in the present. That is, it’s not entirely real, but is composed of representation and memory, the present self made of a past self, as the past is made of, or created out of, the present.

The problem is that Sacco’s manipulation of artifice and memory is not always so deft. In that page we looked at earlier, for instance:

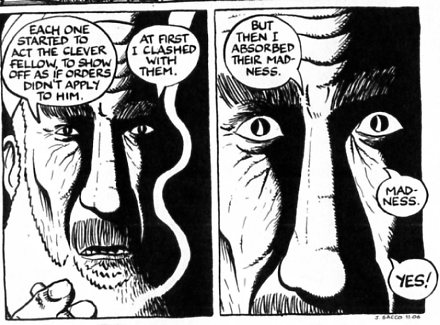

The cartooning turns the Israeli soldiers into deindividualized, snarling bad-guy tropes, all teeth and slitted (or entirely obscured) eyes. Is this how the Palestinian’s are supposed to have seen them? Or is it how Sacco sees them? And is the acknowledgedly subjective nature of comics supposed to make us question this demonization? Or is it supposed to excuse it? Or, as perhaps the most likely possibility, has the impetus for dramatic visuals been catalyzed by comics’ history of pulp representation to create a pleasing collage of villainy from which readers are encouraged to pleasurably recoil?

Or another example:

This is one of a number of times when Sacco zooms in on a grizzled Palestinian fighter, dramatically showing us his crazy eyes. As with the thuggish snarling Israelis, the formal contribution of comics here has to do less with emphasizing subjectivity and physicality, and more to do with the pleasures of pulp tropes. It’s Sacco’s own “Muslim Rage!” moment.

From this perspective, the advantage of comics as a form may be less the meta-questioning of the journalistic project, and more its unique ability to present itself as serious art while simultaneously coating its earnest reportage with a sugary dab of melodrama. One can debate whether this is ethically or aesthetically desirable, but either way it’s clear that Sacco’s comics provide something — a mix of high-art validation and accessible low-art hints of pulp — that is uavailable in prose or video long-form journalism. I don’t necessarily like Footnotes in Gaza that much, but I have to grudgingly admire its creator’s marketing instincts in finding and exploiting such an unlikely genre niche.

Those hints of pulp devalue the work to some extent in my book (that’s my main beef with Krigstein’s and Feldstein’s “Master Race”), but you know that already.

Has anyone talked about Sacco’s use of pulp tropes? I didn’t read a ton of reviews, but my impression is that it’s not something that’s been much talked about (though I could be wrong…?)

The focalization and ocularization problem is interesting though… I never thought about it before, but Sacco’s work almost demands such a scrutiny.

As for “why comics?” I would ask “why not?” instead.

I don’t think so. It’s almost always: Sacco was influenced by Crumb. Crumb, of course, comes from pulp land, so…

“The focalization and ocularization problem is interesting though”

Ummm…could you explain that? I have to shamefacedly admit that I’m not sure what you’re talking about….

Re: why comics? Why not? is a reasonable answer…but I did try to explain why there might be some reasons not to….

Wait…by focalization and ocularization, you mean the problem that Sacco is representing everything you see? Is that right?

Yes, it makes sense that the pulp influence is snuck in via Crumb.

Sacco’s self-presentation is obviously Crumb-influenced too…and I think is also something of a problem. Crumb’s dramatized self-loathing just seems out of place and inappropriate. You see someone’s house get bulldozed and someone else getting tortured, and then there’s Sacco just about screaming, look at me! I’ve got low self-esteem! Pity/love me! It’s just not ideal….

Those terms come from narratology. Focalization is a Genettian term. Ocularization was coined by François Jost, I think.

Again, that’s one of my main negative criticisms of Sacco’s work: his cartoony self is just out of place. I blame Crumb.

Noah: Here’s an article I wrote on focalization and ocularization in comics a few years ago: http://madinkbeard.com/archives/talking-thinking-and-seeing-in-pictures-narration-focalization-and-ocularization-in-comics-narratives/

It seems like you answered your own question about why comics (and Domingos supplemented it with the “Why not?” answer), but as one of those comics fans who bristle when the question is asked, I think there are tons of reasons why comics can make for good journalism. I especially like the way Sacco recreates the past and places it alongside the present; while that’s something that could be done in prose or film (although the latter would necessitate either archival footage or recreations/reenactments, which would highlight artificiality), the literal side-by-side juxtaposition that drawings in panels provide can’t be recreated in another medium. Sacco does such a thorough job of getting the details right that even though the incidents are filtered through his point of view, you can be assured that it’s as close to reality as possible.

I think Sacco is really good at evoking the “feeling” of the events he depicts as well, if that makes any sense. It’s a small touch, but I always like the way his captions are tilted at an angle, which manages to give them a sense of urgency or excitement. It’s just one thing he does that can convey the chaos of war, violence, etc.

I dunno, there are lots of other arguments I could come up with about Sacco specifically and comics journalism in general; I think it’s a pretty valid form of nonfiction. Maybe people consider it more “artificial” than prose or film, but the former is just as subjective, and the latter can use any number of methods like editing or music to shape the narrative. I guess you have to enter into a sort of agreement with the author that they’re going to depict things truthfully, and Sacco certainly seems to hold up his end of that bargain. In fact, he uses the language of comics really, really effectively; there’s a reason he’s so celebrated for what he does.

So, yeah, I guess I’m saying that I’ll go for the “Why not?” answer as well.

I almost mentioned the text boxes. There something I wonder about as well. It seems to push for urgency and excitement…but is that a good thing? Ominous music in documentary films as an analog makes sense, but I find that dicey too. Why are you ginning up excitement, anyway? Surely the story in itself is horrible enough? Why the pulp adrenaline rush?

I do like the way he juxtaposes past and present, though, as I said in the piece. I agree with you there, Matt.

Thanks for the link Derik; I’ll check that out.

The question you ask about “whose view is this” of the Israeli soldiers is a focalization question. In those scenes, we are getting first person verbal testimony (as retold by Sacco, of course), and so it opens up the question, “Do all of these brutal Israeli soldiers look and act the same because Sacco wants us to see them that way? Or because that’s how the first-person witnesses experience/describe them? Or because Sacco thinks how they would have been seen by the witnesses? etc.” Is this Sacco’s view (straight first person narration), or is, supposedly “focalized” through the witnesses telling their story? It’s a question that can’t really be answered by recourse to the text, but it’s an important one. (Is Sacco lumping all members of a group together…a potentially racist or ethnocentric move…Or is he trying to convey the experience of his interview subjects?). I do think there are times in the narrative where some of the Israelis are humanized and individualized, undercutting the sense of these scenes somewhat…Though, in general, it’s the Palestinians who are complex and 3-D individuals, and the Israelis who are more “of a type.” On the other hand, the reverse portrayal, is, of course, more common in the popular media. Do 2 wrongs make a right, then? I don’t know…it’s these questions that made the book interesting to teach (potentially, anyway…many/most of my students didn’t seem that interested).

They’re definitely interesting questions and issues to me, at least. I’m not sure Sacco is always entirely on top of them, would I guess be my point.

I can recall at least one specific, focused example Sacco has given in numerous interviews as to what benefit he sees in using comics: he can present environmental or visual details unobtrusively or repetitively in a way that other mediums cannot. He has spoke about how his drawings of the West Bank allow him to depict, for example, the ubiquitous presence of children and of mud without having to repeat at the end of every sentence “and the ground was muddy and there were kids everywhere.” You feel that impact through background drawings. On the other hand, were this a documentary, he would be entirely dependent on stock footage or b-roll of contemporary Gaza– and I imagine stock footage of 1956 Gaza is hard to come by, if it exists. Thus he is able to give his narrative much more visual impact than the “talking heads” would of a documentary. Plus, of course, he gains the ease of access and portability that a book has over a documentary, as well as the length and depth of the book (this documentary would be hours long if all the dialogue was read out loud). These are all relatively superficial advantages comics has. I’m sure you could come up with more.

Other reasons: Sacco has said he appreciates the necessary slowness of comics, which requires abandoning any sense of timeliness in favor of “slow journalism.” Carrying a sketchbook and pencil into a strange location is much less obtrusive and alienating (and much cheaper) than carrying expensive camera equipment. People react very differently when you put a camera on them.

Those are good reasons! I’m not sure they counterbalance my problems with the book entirely. But again, I agree that the ability to go seamlessly back and forth in time is one of the strengths of the book.

“Reading Joe Sacco’s Footnotes in Gaza, I kept coming back to the same question. Namely — journalism as comics? Why? ”

Just because is what Sacco wants. If he had chosen photography, written report or documentary, it would be right too.

The problem of the “truth” is the same for the journalist, the writer, the historian. They all have that problem, each one in their own language of course. And, yes, also the documentary filmmaker also has his own “emphatic” or “melodramatic” formal devices. And no modern historical account (as Footnotes from Gaza is, to a great extense) is proposed as “transparent” or “The Truth”, at least if we’re talking about a good historian… and if the historian is proposing as such, he’s is lying. Something Sacco try not to do when he emphasizes again and again, whenever possible, his subjectivity as narrator.

Neither I don’t understand the “logic” why, if you find specific failures in a comic, question the general comics form. The same could be done with issues that don’t convince you in a particular film documentary—>Why documentary? The question makes no sense.

Unless you think that comics are only suitable for * certain things *, but * not others *.

“but I have to grudgingly admire its creator’s marketing instincts in finding and exploiting such an unlikely niche genre.”

This sentence, Noah, which becomes your final answer to your own question (why?), shows clearly that you don’t know Sacco’s career nor his vocation. It’s not a matter of ‘opinion’, but to know facts of reality.

Sacco lived badly during the nineties and early 2000s just because his comics didn’t give a lot of money, and he had to combine them with other jobs to make ends meet, saving to pay his travels to Gaza or Sarajevo, etc. Marketing? He was doing comics for years when almost nobody cared, nor “big publisher” hadn’t noticed at all.

So, Why?

Domingos: “Why not?”

Absolutely right. I add another reason.

Again, just because it’s what Sacco wants to do. Because he is a journalist, and, at the same time, a cartoonist.

So Noah, you are entitled to value Sacco’s work, but not to question his reasons for doing journalism in comics. And if you are not aware of what kind of thinking indicates your question, you should think again.

That’s right Pepo. I still treasure a drawing that Joe gave to me, back in 1993, of his putative next big hit (following the Ninja Turtles, I guess): the Human Poultry Item. I’m glad that he chose another career options and I’m quite sure that the poultry item was a joke.

Drawing is excellent at visualizing complex objects, situations or processes; narrative/sequential drawing even more so. The ultimately subjective monstration and simplification of the cartoonist isolates and elucidates pertinent information, making things clearer. I remember in some ways getting a better sense of the war in Bosnia from reading Safe Area Gorazde than I had from assiduously watching TV news reports and following the events in the newspapers as they unfolded. As good a reason as any to use comics.

Sacco is very aware of the anonymous representation of the Israeli soldiers in “Footnotes” — he has addressed it in several interviews, though I can’t find a link right now. As far as I remember, it is an effort to focalize, as Eric says, the point of view of his witnessess without the unnecessary “noise” — i.e. subjective interpretation by the cartoonist beyond and counter to the accounts he was working with — that individualized features would generate. Although the comparison is otherwise assymmetrical and the intent and focus are different, it’s somewhat similar to the way Goya depicts analogous situations in his famous “Third of May” and “Disasters of War”

I could be misremembering though. Anyone got a link?

“He was doing comics for years when almost nobody cared” — reminds me of more good reasons. Comics, especially when Sacco started, used to fly so far under the critical radar of wider society that you could get away with doing a book about Palestinians without any pushback, or, y’know, attention. On the other hand, the novelty of “Hey, it’s a comic about Palestine” probably got him a lot of readers and attention that he wouldn’t have gotten from (yet another) book or documentary. I mean, Edward Said wrote the introduction to the collected ‘Palestine’ volume.

Pepo, I don’t see why a critic shouldn’t be able to think about/question medium or genre choices. It seems analagous, perhaps, to thinking about how a film version of a novel changes or affects the experience. Why make this book into a movie? What is gained or lost? Journalism isn’t traditionally done in the comics genre. I think it’s fruitful therefore to think about what happens when you do journalism as comics, and whether the benefits offset the downsides or not.

Along those lines…I think that all journalists have to deal with the problem of truth, but it’s reductive to say that it’s the “same” no matter the medium. Different mediums have formal and historical differences. Their relationship to truth is different. That’s what I point out in the essay.

As for his marketing savvy — Sacco obviously isn’t hugely successful financially, or at least hasn’t been, and I certainly wouldn’t claim that he’s doing what he’s doing for money. But he has found a way to attach aspects of cachet as an artistic genius to journalism, where such cachet doesn’t generally accrue, at least not in that way. That’s a marketing success, whether he (or you) want to see it as one or not.

______

Ethan, I’m sure Sacco didn’t want to not be noticed. IF that was his goal, he could just have not created anything at all, and then he would have been even more successfully ignored, right? I agree, though, that making it as comics was in some regards an astute marketing move…and I said so in the essay.

Oh, I’m just rattling off ways that I think Sacco’s work is better as comics, I’m not necessarily ascribing that as motivation to Sacco. But I do think there’s a difference between “making work that flies under the radar of the mainstream” and “not making work.” Comics’ former position as the red-headed stepchild of American cultural production meant that Sacco could avoid the sort of intense critical pushback that any work sympathetic to Palestinians gets until he became a relatively big name.

I just find it hard to believe that the goal of an investigative journalist is to have fewer people read his work. He’s an advocate. Advocates want to draw people’s attention to the cause their advocating.

Pingback: Comics A.M. | Could NYCC become ‘the comic convention’? | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Again, not ascribing it as a goal of Sacco’s, merely a side effect of publishing as a comic book (ESP as a comic book, as opposed to “graphic novel”).

Ethan, I collected some of your comments into a post here.

“Artistic genius” — Isn’t the only person who has called Sacco that himself, in his very first, very ironic publication?

In any case, artistic merit is perhaps not normally associated with prose journalism, but it’s routinely used as a framework to assess the work of photographers and filmmakers working in a similar vein to Sacco.

Ah, ok that’s not his first publication, sorry, but it *is ironic.

Some photographers, yes, maybe. That’s a good point. But…filmmakers? That torture documentary I linked to…there really was no auteur function there that I could see, and I think that that’s not untypical.

What about Michael Moore? He kind of stretches the definition of “journalism” though, or just completely breaks it. He’s more of an essayist or editorialist, I guess. Okay, how about Werner Herzog? His documentaries are very artistic. And even the less personality-based documentarians who stay off-camera still have an auteur-ish style, such that one can recognize a film by, say, Errol Morris through the editing choices, music, etc.

Moore is definitely not seen as an artist, though. A provocateur, maybe. I’m not super familiar with Morris or Herzog…but they’re not doing investigative journalism, are they?

I haven’t seen it, but Morris’ Standard Operating Procedure was all about looking into what happened at Abu Ghraib. I haven’t seen many of his films, but he’s somebody I want to see more of.

Herzog is probably more interested in painting a portrait of the people or places his films are about. Grizzly Man did some investigation into the life of its subject and the events surrounding his death, but it was probably more about the person overall. I highly recommend checking out his movies, both fictional and nonfiction; he’s pretty amazing.

I dunno, I was just trying to think of some examples; maybe investigative journalism is more dry and fact-based, less prone to artistic interpretation. There is that guy Nick Broomfield who did movies about Kurt Cobain, Tupac Shakur and Biggie Smalls, and Aileen Wuornos; he seems to insert his own personality into his films while investigating the subjects. I’ll have to see if I can find any other good examples; there’s no reason documentary film can’t have as much auteurism as comics or prose, is there?

I don’t think it’s an issue of it being impossible; it just seems to happen less.

Chris Hedges seems like the figure most analogous to Sacco, right? They’ve worked together and share a similar agenda and mission. Hedges is widely respected as a thinker and a writer — but he’s not considered an artist in the way Sacco is. And that has everything to do with the medium they work in, I think.

There’s some irony that working in comics makes Sacco an artist… he found the rare niche where comics ‘elevates’ the form, or at least its marketed that way…

Well, I think Sacco is in the genre of “New Journalism,” which straddles the line between journalism and art. His stuff has some similarities to The Armies of the Night, where Norman Mailer mixes his self-aggrandizing/self-deprecating schtick with coverage of the March on the Pentagon. I think Sacco’s use of fictional comics techniques could also be compared to the use of fiction-narrative techniques in Mailer’s The Executioner’s Song or Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood (neither of which I’ve read).

Have you read Palestine, Noah? I thought the sequence of the guy being tortured, hallucinating, and finally being released into a street filled with Israelis going about their everyday lives made very good use of the comics medium.

Footnotes in Gaza and some short stories is all I’ve read of his.

I have a hard time considering what Sacco does journalism, or as strictly analogous to documentary film, even documentary with an intrusive authorial presence like Michael Moore’s. To me the analogy is docudrama, like The Killing Fields. Sacco may be very rigorous in not falsifying any facts, or changing the text from his transcripts, but as has been pointed out, everything is re-created. I dislike re-creations in documentary films, anyway, but could you even call a documentary that is 100% recreation, a documentary?

And if it was sock puppets, would it be a sockumentary?

dan mazur:

Well, does Ken Burns count as a documentarian? His Civil War stuff is all photos and people reading letters aloud, but people don’t seem to consider it less “truthful”, do they? Is prose journalism, in which the author recreates situations and conversations through text, also disqualified? Comics are arguably more representational of reality than even a transcript of an interview, since the artist can capture expressions and demonstrate body language, and even imply vocal inflections through lettering or other comics tools.

Really, any form of journalism is open to authorial interpretation, so the idea that Sacco is less legitimate (or doesn’t fit into the nonfiction category) is one that I definitely take issue with. You might not be saying that, exactly, so if I’m attributing a statement to you that you didn’t make, I’m sorry. But the fact that Sacco’s comics are different than documentary film is kind of obvious, since comics and film and different mediums. That’s not a problem, it’s just a different way of communicating information.

Well, I think Sacco’s work has great value, and is definitely non-fiction. As far as Ken Burns, his films are historical documentaries. Photographs are historical documents. Letters and first-person written accounts are as well, even if the voice reading them on the soundtrack adds an interpretive element. Sacco’s cartoons are 100% artistic interpretation – okay, prose journalism will always be interpretive, but a good faith effort can be made to eliminate as much “slant” as possible. That can’t be said for comics – the artist can’t really “capture” expressions, as a camera can. A writer can’t either, of course, but to me, things like descriptions of facial expressions can be part of prose journalism, but they are the most unreliable part, the part least valurable to it as journalism. In Sacco’s work, his interpretation of appearance, expression, gesture, is central. And that’s a fictionalization, even in the context of non-fiction.

But I do think that I overstated my position, on reflection. What Sacco does is journalism, and for the most part he does it very well. It’s just a very specific type of journalism with specific pitfalls and dangers, as in the example of the soldiers with the clubs that Noah highlighted.

This is a dumb post.

I wonder why Joe Sacco, well known for his comic journalism and never shown to have an interest in other artforms, chose to do his latest project as a comic? Are you kidding me?

It wasn’t a question about Joe Sacco. It was a question about why anyone would want to do journalism as comics.

But you’re welcome to think it’s dumb if you’d like.

(This mostly re. the page with the dehumanised Israeli soldiers: )

The juxtaposition of the soldiers with the uniformity of the multiple testimonies turns the victims’ statements themselves into a kind of bludgeoning maelstrom: the author is showing us the process by which his impression and opinion of the episode was so formed, simultaneous with the depiction of the act itself. There’s a remarkable efficiency there, arguably entirely unavailable to different media, which perhaps goes some way to answering the central ‘why comics’ question, even leaving aside the considerable narrative/affective force the technique affords.

In terms of how this effects the integrity of Sacco’s journalistic objectivity, it’s his cards on the table moment (one of several in the book iirc): this is what he judges to have happened on this day, this is what it felt like to be either victim or perpetrator (i.e. to be one of those soldiers and act so inhumanely was to relinquish one’s right to be depicted during those moments as human), this is how morally defensible the crime was. To have a position, to say with clarity ‘this occurred – in this fashion’, isn’t (or at least I suspect it isn’t, not an expert) a betrayal of journalistic ethics.

“Photographs are historical documents.”

Not always.

“… That can’t be said for comics – the artist can’t really “capture” expressions, as a camera can…”

He can if he draws from the pictures that he takes.

“Sacco’s cartoons are 100% artistic interpretation ….”

If it was 100% interpretation then he’d be making it all up. You’re underestimating by a huge degree the amount of photo research he does. The intro pages to his Palestine Special Edition may help clarify this a bit for you.

“….could easily have been presented as an agitprop book or as an agitprop documentary film.”

No. To double up on Ethan’s point, just how easy would it have been to bring cameras into the occupied areas? Films can be made cheaper than ever before these days, but that doesn’t mean filming inside there would have been an easy task.

Another reason for being for this type of journalism is that it can be much easier for people to open up to you if you don’t have a camera. In one of the earlier Palestine collected editions Sacco talked about how interview subjects would warm up and understand what he was trying to do much quicker after seeing his artwork. The immediate appeal of comics helped people open up to him in a way that one couldn’t imagine if he was a filmmaker or writer. It’s not just mud and children that Sacco was able to show more of. He was able to show more of everything.

Jack’s mention of the “New Journalism” is spot-on. Definetly one of the influences that Sacco has explicity mentioned in certain interviews. Chris Hedges and Sacco share similar political outlooks, but they are miles apart when it comes to the level of stridency in their respective output.

“Everything you see in Footnotes in Gaza is created and represented by Joe Sacco.”

Yes, but again, it’s extensively researched beforehand.

I don’t disagree that the closeup panels of the “grizzled fighter” are trite. But it’s reductionist to say that it came via Crumb. One could find that kind of sequence in various types of tv shows and movies.

I don’t think Domingos was saying that panel in particular came from Crumb. More that Crumb is the main influence,and Crumb is very pulpy. So less a particular visual reference than the general influence of pulp can perhaps be seen as coming through Crumb.

Oh, and I have to say I didn’t really consider the technical aspects which you and others have pointed out, and (as I said above) those are good reasons.

Pingback: Comics Journalism Reading List | Kenan'?n Akademik Penceresi

Pingback: Graphic Journalism: Insightful or Subjective? | Journalisticampus