I notice the air getting very thin when I’m in a discussion with cartoonist peers and the subject of furries is brought up (oftentimes by myself and my friend, the glass of wine), filling the vacant atmosphere like a silent fart. To the sub-culturally literate who know and love to hate us, we are mad, shallow tacky perverts; aesthetically handicapped loser-kin often more adept at creating elaborate webs of internet drama than art, stories or comics of any value to people outside of the fandom. This is a half-truth.

There are artists working within and at the margins of the furry subculture producing spectacularly daring, inventive, funny, hyper-aware fiction who nevertheless feel deeply insecure about associations with such a maliciously misunderstood subculture. There aren’t many works in the canon of respectable comics which feature anthropomorphism in furry style ™. Instead of majestic, inventive comics like Krazy Kat, furry style was initially shaped (as an offshoot of science-fiction fandom in the early 80s) by admiration for Disney cartoons (Robin Hood, woof!) and advertising mascots. Our foundational sensibility is gene-spliced super-soldier pulp paperbacks, Tex Avery and the naïve dom/sub sexuality of old Fox and Crow funnybook covers. And those comics suuuuuuuuuuuucked. Sucked the paint off a barn. The vicious aside about funny animal comics near the end of Michael Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay stings all the more bitterly because woe, it is so so true.

So we furrs pounce when a sophisticated mass-market comic featuring talking animal-people gets a little, or a lot of love from readership and critics. The Blacksad series by the team of writer Juan Diaz Canales and illustrator Guarnido might be the holy grail of furry respectability within the world of comics. The stories utilize a cast of upright-walking humanoid animals that exist within a model of human behavior, yet their individual animal speciation informs their human-like character and personalities. These are conceits that furries can claim as their own, regardless of actual authorial involvement in the subculture. (This applies retroactively to previous iterations of pop-anthropomorphism as well —but let’s not get sidetracked.) Blacksad has cred, it’s popular, and it’s very furry. It’s also very troubling if it’s the type of material that we’re going to hold up as a standard of excellence for anthro comics with a broader market appeal than furaffinity.net.

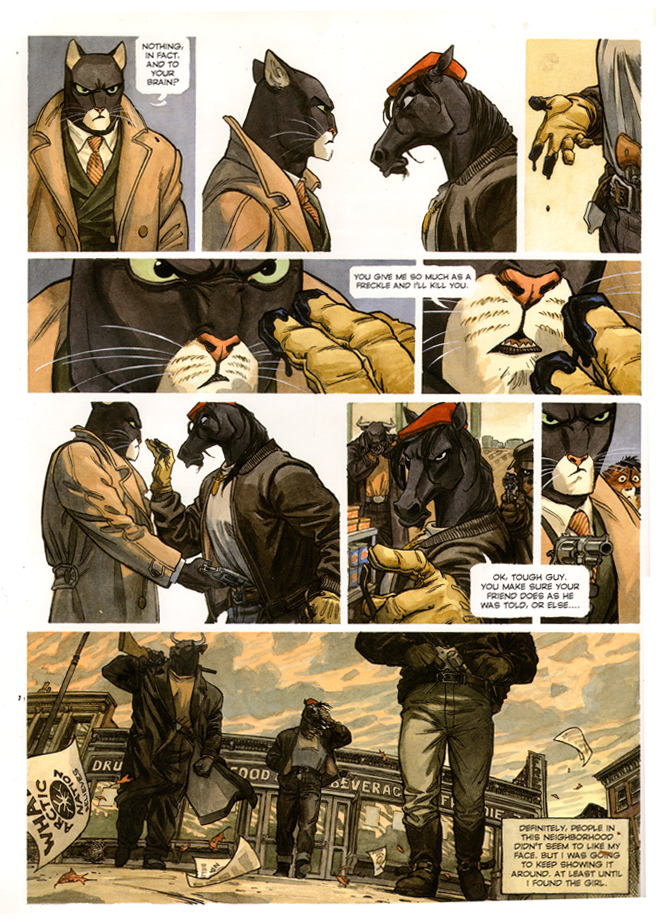

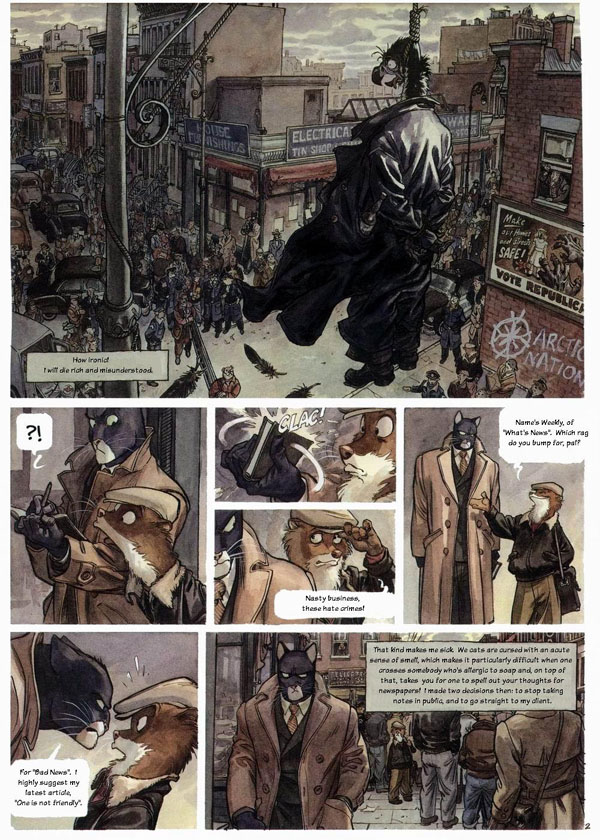

Blacksad has been recently reprinted in hardcover, bundled with the unreleased -en Anglaise- Ame Rouge, by Darkhorse as well as a second volume of new material which I have not yet read. The previously released second volume, Arctic Nation, won a Harvey award in 2005. It thrusts our hero, the titular John Blacksad, into an intrigue set against an atmosphere of mid-century racist tension and violence outside New York City. Rather than a sober European critique of American racism and class struggle (haha let’s not trouble ourselves with that thought), Arctic Nation is unfiltered, earnest pulp. It begins, subtle as an asteroid collision in your nana’s parlour, with a lynching. On page 2.

Backing up a bit. I can’t offer much in the way of relevent analysis or anything new to say about racism, or depictions of racism in comics per se. I don’t have a seat at that table. Furthermore, the Blacksad universe is very clearly meant to represent a pulped version of reality, and it’s up to discussion whether fiction in this vein should be judged according to its reflection on political reality or read on the terms of the self-contained universe of its creators’ imagining. But the animals Guarnido populates the world with are meant to suggest inferences about human traits, including racial ones. And I do feel, as a furry, like I have something to say about their use in Arctic Nation (or the use of various species to represent different ethnicities and nationalities of human beings in the first place. Hint: it’s a really bad idea!).

The second volume in the Blacksad story follows our hero John, the taciturn tom-chat noir private eye, on an assignment into a suburb called the Line, which is in a state of social upheaval following the decline of its post-war manufacturing boom. The world, entirely populated by a managerie of anthopomorphic animals, expands in complexity here. A coalition of animals of various species who share in common their white fur, many of whom occupy ossified posts of old social power has hardened into a hard-right group -a mixture of the Ku Klux Klan at the height of its influence and the American Nazi Party of the 60s and 70s- that overtly terrorizes everyone else. The only organized resistance, the “Black Claws” — an obvious parody of the Black Panthers — is cast as equivalent in their odiousness to the white hate group.

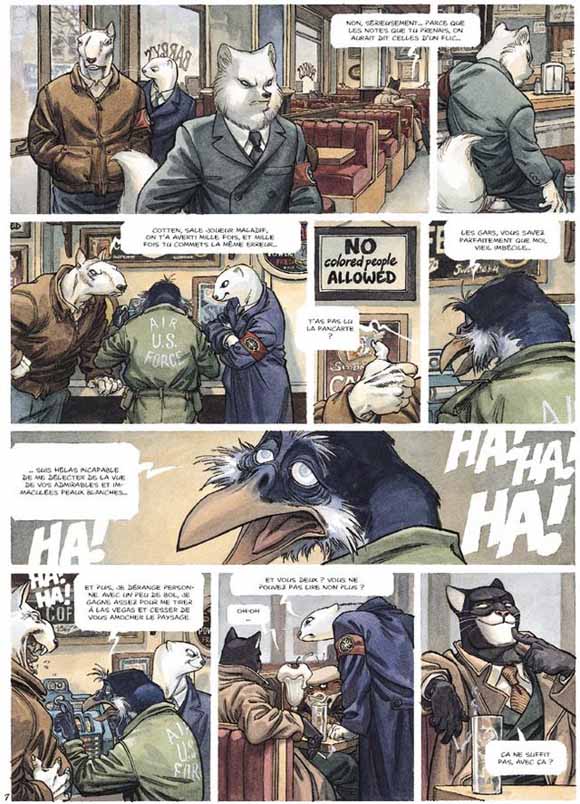

This brings up an interesting point that is not readily apparent in the first volume of Blacksad. John, a black-furred cat, is in terms of a human analog, a black man, and is treated as such — but with a caveat. He has a patch of white fur on his muzzle which affords him some access to interactions with the white-furred power brokers within the neighborhood. This concept of his “whiteness” is directly alluded to on page 9 of the iBooks paperback printing when he is hassled by Arctic Nation thugs in a diner that conspicuously displays a notice that reads “NO colored people ALLOWED.” He rolls his eyes and offers a deliciously smug, self-confident grin. “This here isn’t enough?” The initial victim of the AN goons’ attention, an old blind crow wearing a US Air Force Jacket, a possible nod to the Tuskegee Airmen, isn’t so lucky. He also has white facial markings but they are signs of age, and without John’s gift of brute strength (applied with gusto in the following page) he is an easier target.

One of the most interesting characters in the story, for many reasons, is Weekly, the sidekick and comic relief to John’s turgidly upright straight man act. An unctuous tawny-furred mustelid, Weekly reads as white but is unsympathetic to the Arctic Nation’s fanatical racial vision. He is a target of scorn by the white-furred citizens of the Line, though this could be attributed to his unsavory profession as a weasely tabloid reporter or his “European” approach to hygiene (his nickname stems from the supposed infrequency of his change of undergarments). His exclusion from the ivory racist clique also exempts him from the system of oppression against black-furred animals in the Line. He is familiar, actually chummy, with our hero from their first interaction. The only system of oppression in Blacksad’s universe is at the hands of a white nationalist extremist population which has the means to mobilize against a specifically black one. Red or brown or orange fur occupies a “neutral” territory.

John is on a case of a missing child whose mother is reticent to report her disappearance. John is working on behalf of the girl’s concerned teacher, Ms. Grey (symbolism!). The “plot” that transpires hurls him neck-deep into a preposterous, Oedipally-fraught revenge scenario whose architecture involves murder, incest, the previously-mentioned abduction and plenty of manipulation through the withholding and dispatching of gratuitous sex. In spite of all this spice, it’s not all that interesting. A polar bear named Karup (wordplay!) falls in love with and marries a deer, but their relationship is poisoned by his lust for power and inclusion in the white-furred elite of the Line. He abandons his pregnant bride to die in a snowstorm (symbolism!) and goes on to become chief of Police. She survives and gives birth to two fraternal “twin” daughters, a white-furred polar bear and a vampy, heavily caricatured black deer (more symbolism! nonsensical biology!), but separated from her husband’s love, she wastes away into alcoholism. (An aside: if the case were to be made for Arctic Nation being in fact a hideous racist publication, the panel where we are made to leer at the deer’s degradation and death while her daughters stoically look on would be exhibit A. It’s skillful cartooning at its most rotten, twisted, and cruel). Moving on!

Karup’s daughters, now adults, set their revenge against him in motion, Jezebel (a Madonna/Whore cliché, goddamn with the symbolism) marries him, though their relationship is icily chaste. She meanwhile uses her sexual wiles to foment a power struggle within the Arctic Nation. Dinah meanwhile orchestrates the kidnapping of her own daughter to exploit standing rumors of Karup’s perverted predilections and set up a coup for his ambitious subordinate Huk. Just about everyone dies gruesomely, leaving Jezebel with her thin victory to cloak her grief and Blacksad to righteously brood over the twisted nature of the world.

Throughout, John does little actual detecting. He slinks throughout cross-sections of the Line and throws a couple of well-placed elbows when things get hot while the sisters’ plan falls into place on its own. He sneers at the endogenous old blue-bloods, the white tiger Oldsmith and his mentally-handicapped Cheetah son whose only purpose is as a tidy avatar of rebuke. He tussles with a few representative members of the Black Claws, two beasts of burden and a Rottweiler. Acting as a typically crass reduction of black resistance movements, the lead black toothy horse first intimidates Weekly to publish some piece of propaganda and then taunts John for his whiteness. “What happened to your snout, brother?” he asks before attempting to smear the white patch on Blacksad’s muzzle with motor oil. John responds by plugging his revolver into the assailant’s waistline. It’s no accident that this Claw is a horse – what with their prodigious members. You emasculate me, and I’ll emasculate you! Either way, John will have none of your Black Consciousnes, sir. Whiteness unbesmirched, John fumes in the car outside after the claws disappear into the foreground and from the story altogether. “You’re not going to publish that crap, are you?”

I might wonder similarly at Blacksad’s editors. Guarnido employs honed caricature, meticulous detail and a sophisticated color palate in service to a crude and unsophisticated pulp rag that exploits images of American racial and class struggle for cheap moralizing while rendering nothing of any value. Anthropomorphism is a give and take, and often works better when we allow the animal traits (themselves human projections) to reveal character i.e. Sam the Clever Fox or whatnot. Shoehorning human society onto one or several unsuspecting ecosystems and tossing them together in a fantastical New York is simplistic and prone to breakdown. The relationship between the arctic fox and the snowshoe hair is warped beyond any sense within the boundaries of Arctic Nation’s universe. Are they bonded as brothers in attempted domination of the vampire bat, the grizzly bear, nay any creature not possessing white fur, an arbitrary gesture of humanity draped over animal cyphers? We can use funny animals to talk about funny peoples, but my god we can do so much better than this turd.

Wow, this does sound terrible.

I like your parenthetical exegesis!

Suat also kicked Blacksad a bit back here.

Suat’s take was slightly different; he focused more on the staleness of the genre exercise rather than on the anthropomorphic confusion and/or the idiocy of the racial message.

i had missed Suat’s article when i began writing this, but it’s great.

I read the older edition of three Black Sad stories. I thought the racism story was extremely stupid. Stupid to the point of offense, but not offense such as “this is racist and I’m offended,” but offense in that smug way that many European writers look at American cultural issues.

It’s laughable because the outsider critique takes itself very seriously when it skewers us savage Americans but it doesn’t realize that it (the outsider critique) shows more of its own ignorance of the issues on the ground than it makes a dent in the problem.

Anyway, it’s a pretty comic. Pretty and brainless.

:-)

There must be some European discussion of American racism somewhere that is insightful/useful, right? There’s Bartoleme de las Casas — but surely something since then?

The way the racial issue is presented here in Blacksad reminds me a little of Orientalism? It seems like a projected fantasy which has everything to do with Europe’s desire for exotic fantasia and sleaze and prurience, and little to do with anybody actually living in the US.

i seriously doubt that Arctic Nation was intended as an earnest critique of American racism. That would be… unimaginably hubristic considering the work we have in front of us. Noah might be more on the ball – it strikes me as in the same vein of exoticized Americana as the cowboy stories some European audiences are quite fond of. In that light it still takes incredible balls to romanticize racial struggle. Either way you look at it the book is a moral and conceptual failure.

i skimmed over this so i’ll bring it up here. There’s a basic test of logic every anthro writer must confront themselves with before unleashing their work into the public. What happens when two “species” fall in love and reproduce? i get the distinct impression that Diaz + Guarnido conceived of the conceit of the twin daughters before they established the logical consistencies of their universe.

i’m willing to run with stretches of biology, you have to break all the rules for furries to even exist, but we have to give it a little more thought. If genetics work like we see them work in this story, and the uterus is basically a xerox machine, how did individual speciation develop in the first place?

It’s impatient and clumsy worldbuilding.

It seems like in terms of speciation, they’re relying a lot on the drawings to make it work. That is, the anthropomorphizing is extensive…a lot of the characters (especially women?) look basically like human beings with furry ears. In that context, the fact that the furry ears are supposed to be “deer” doesn’t matter that much, maybe?

Of course, the fact that men and women seem (at least from what’s here) to be represented almost as different species raises its own problems….

Anthro women being worlds away more “anthro” than men is a total male gaze cliche, and in a way preceeds furry consciousness.

precedes*

As much as I like the pretty pictures the plot has been a weakness in all of the Blacksad comics.

Even in my ignorance of those matters the racial allegory in Arctic Nation also struck me as absurd. Black and white animals, what about the rest? It also doesn’t really seem to fit with the rest of Blacksad’s world, as if racism is just a problem in that particular suburb.

As for European discussions of American racism, I can imagine your exasperation if Franco-Belgian comics are what you have in mind, I’m reminded of Gunnar Myrdal’s study “An American Dilemma” from 1944. I haven’t read it and don’t know how well it holds up but it seems to have had some influence.

And as you had mentioned, the reduction is self-congratulatory and oversimplifies contemporary American racism. When Blacksad goes to The Line it’s like he’s descending into this hell-pit tucked away from the Forward-Thinking, Safe Confines of the City. Like, “Ah, yes, John experiences tension on behalf of these cracker animals when he goes to this rural nowhere-town, but it’s a good thing he can return to The City, where there is no racism, right???”

Reading this actually got me thinking about a lot of the troubling implications the species-related coding in Blacksad affords; I wonder how one would interpret the reptiles in Blacksad, who are generally antagonists across the board, with no redeeming qualities. We have this apparently ‘anti-racism’ story but we also have this framework in the world that establishes that there are Bad Animals in Blacksad.

(Granted I haven’t read all of Blacksad and don’t know if there are any good lizards or not, this is based on having read everything up to what has been translated in English)

Rory: it just will not do when John emerges, Dante-like, from the Line and returns to the city where he is the social equal of his G-shep police chief friend Smirnov. But this strikes me again as more lazy worldbuilding. “Time to put together the racism story. Next on the docket: communism, moving along, moving along.” & the reptiles in the other Blacksad stories are definitely caricatured in a racially coded way.

Tom Spurgeon politely critiques one of the Blacksad books: http://www.comicsreporter.com/index.php/cr_review_blacksad_a_silent_hell/

I had been meaning to read Blacksad for a while, but lately I’ve been hearing that it’s really not very good, and I had no idea that it involved this ridiculous take on racism. Sounds like I shouldn’t bother, or maybe I should just look at the art.

As for other furry-approved (that’s a term I never expected to use) funny animal comics, what’s the “anthro” community’s take on Bryan Talbot’s Grandville? I like that series quite a bit, and it’s got some neat steampunk/alternate history stuff to go along with the occasionally sexy animal adventures. I guess I’m saying that if this is going to be a regular roundup of furry comics, please cover that one next.

Grandville is generally well regarded, and is distributed by Furplanet, though i have not read it just yet myself. If Noah would like someone to write about furry comics good and bad on the regular, i would be amenable to that.

I’d be happy to have you write about furry comics regularly, Michael. Email me?

Noah Berlatsky said:

“That is, the anthropomorphizing is extensive…a lot of the characters (especially women?) look basically like human beings with furry ears. […]

Of course, the fact that men and women seem (at least from what’s here) to be represented almost as different species raises its own problems….”

michael (funnyanimalbooks) siad:

“Anthro women being worlds away more “anthro” than men is a total male gaze cliche, and in a way precedes furry consciousness.”

Yes, that’s been one of the things that’s been keeping me from reading Blacksad (aside from not being into pulpy noir type stuff); the female characters are much more highly anthropomorphized. Regardless of species, the males have heads & faces that largely conform to the actual species appearance with some allowance for human facial expression; the females have human faces with snouts, and human-style hair.

This happens in a fair number of anthropomorphic-animal comics, and it bugs the %$#! out of me; the only reason for doing this is to make the female characters more attractive to the reader (and it doesn’t help that Canales and Guarnido tend to draw all of them as voluptuous 40’s-pinup bombshells), rather than following the actual gender dimorphism of the species or using it for world-building (for instance, how species differences would affect what the various species find attractive). The guys can look like bipedal polar bears in suits; the women have to look like Jane Russell in a muzzle.

And even if you don’t care about the sexism, it breaks down suspension of disbelief to be switching from more-cartoony-humanoid to more-realistic-animal faces of what are supposed to be the same species. It’s distracting.

Why do anthropomorphic women always have human-style breasts? That kind of weirds me out, although I suppose seeing a dog-lady with a set of eight boobs would be even weirder. It might be an exercise in seeing what kind of outfits artists could devise to reveal multiple sets of cleavage.

…this train of thought is gross.

That’s a furry animal story I’d read, Matthew. Reminds me (as so many things do) of a Shel Silverstein song, “The Mermaid,” in which the protagonist finds happiness with a mermaid where the human part is on the lower half, rather than the upper. There certainly are regions that seem to be more important to anthropomorphize than others. It kind of goes from cutely perverse to grotesquely perverse real quick.

Matthew: you started it.

and it’s not gross. human sexuality is an aspect of anthropomorphism that furries are not afraid of or shy about engaging with.

This filters into the general way that women are cartooned in the first place, where their status as a sex object is a defining visual characteristic. From a cartooning perspective, especially for non-furries, if you are drawing a funny animal character that is supposed to read as sexy, humanoid secondary sexual characteristics are a more natural shorthand, and tbh creep people out way less. It’s not an anthro-specific choice, it’s more or less standard male-gaze cartooning with kitty ears.

I literally gave up on drawing anthro comics entirely for years because I was sick of trying to convince people I wasn’t some sort of deviant, malfunctioning neckbeard. (That, and I wasn’t entirely comfortable with being in close proximity to the actual deviant malfunctioning neckbeards, either, offset as they were by a bigger core of reasonable and decent people largely invisible to the internet atrocity tourists any aspiring furry artist has to answer to.) So those first couple paragraphs jumped out at me, and an article on how furry comics became the one untouchable caste and whether it’s possible to turn that around is something I’m interested in reading.

As far as race and anthropomorphism goes, that’s the kind of thing that only really works in a “real world”-esque context if you rewrite or scratch-build a shit-ton of rules. Prejudice makes more world-building sense along species lines, without much consideration for color (a white dog hating a black dog makes a lot less animal-logic sense than a white dog and black dog teaming up to hate any color of cat). And trying to get animals to represent anything else other than their species gets potentially compromised when you try to bring in additional questions of ethnicity into it. Given what they’ve symbolized over the centuries, can lions represent both the African diaspora and imperialistic Britain? Are there hybridized canines that are half-wolf or half-coyote but try to downplay their mixed heritage because passing for dogs leaves them less prone to being othered? If (unless you’re drawing that queasy ‘Kevin & Kell’ comic) predator species don’t literally kill and eat prey species, what kind of social dynamic exists in its place to cause tension? There’s plenty to deconstruct just by going off the idea of a society that tries to play by the pat, simple rules of anthropomorphic stories, especially the essentialist Redwall-style “this species is always evil” typecasting, but being confronted with real-world dynamics getting all up in to complicate things. ‘Blacksad’ doesn’t do that well at all, and I’m not sure if there are any comics that do.

” I’m not sure if there are any comics that do.”

Well, the one most everyone thinks does it well is Maus…though I’m skeptical myself.

np: beautifully put!

a cartooning attitude i have butted heads with in the past is the idea that furry-leaning artists should have to justify drawing anthropomorphic animals as a cartoon choice, as if “i like cute fuzzy animals” isn’t justification enough. The more I think critically about “anthropological anthropomorphization,” the earnest “because i like it” approach is the least problematic.

i believe blacksad begun with this motivation. Drawing this comic with animals because drawing animals is cool. That’s one of the reasons the later injection of a racial element fails so bitterly. They hadn’t thought about the world in that context until the point came up later.

An aside: One specific motivation of using anthropomorphic animals is to deliberately avoid racial politics. I’m not certain this was a motivating factor, but this applies to Walt Kelly’s Pogo. We don’t know what “race” any of the swamp critters might correspond to and we don’t care.

on that note, I’m a big fan of animals which circumvent human racial problems. One thing that my mom would do–and I can only imagine other black families might have done–is buy animal character greeting cards because most of the other greeting cards would have pictures of white people. White people are pretty okay, but it’s very inappropriate to give somebody a holiday card or birthday card of one when the person is very much Not White. Hence: bears.

———————-

michael (funnyanimalbooks) says:

…This filters into the general way that women are cartooned in the first place, where their status as a sex object is a defining visual characteristic.

———————–

Yes; like in http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-N1-ioXPD9dE/TbL9kiFBEII/AAAAAAAAOgc/EXhvkVahUzU/s1600/AlleyOop_1971-08-08_100.jpg

Or: http://www.fpsmagazine.com/blog/uploaded_images/coal-black-724707.jpg

———————–

np says:

…I was sick of trying to convince people I wasn’t some sort of deviant, malfunctioning neckbeard.

————————-

“Neckbeard”?? Googles; finds http://1d4chan.org/wiki/Neckbeards . Yecchh!

Anyone else notice that whenever Guarnido draws drapery or folds it always seems to look like the same type of material?

Good catch! Somebody should recommend he read Burne Hogarth”s “Dynamic Wrinkles and Drapery,” which among other things, details how different materials fold, crease, fall: http://www.amazon.com/Dynamic-Wrinkles-Drapery-Solutions-Practical/dp/0823015874 . Most excellent.

A review and images: http://www.parkablogs.com/node/2426

One section from the book (scroll down) at http://www.tumblr.com/tagged/art-resource?before=1346494419 .

Where we also see, something else the Blacksaad artist could make use of:

“Fantastic Site For Dog Coat Color Genetics — Makes a great resource for canine characters!” ( http://www.doggenetics.co.uk/ )

“…Strangest thread derail ever!”

BTW, anyone remember when the Nazi cats in “Maus” used realistically-drawn dogs to try and ferret out the hiding place of the Jewish mice?

Jason is someone who seems to come at the anthro aesthetic from the side. And while I might be forgetting something super simple and important, the fact that his characters are animals has no bearing on their relationships (or their secondary sexual characteristics… the birds are people with bird heads, cats people with cat heads, etc.). That said, I really feel the anthro thing buys him something, but I’m not sure what, exactly. Part of it is that it puts his stories into allegory territory, which to my mind makes them relatable in a way that is somewhat at odds with what is the otherwise flat affect of his characters. Obviously, this isn’t very thought out, but hey, comments!

To NP: Why, yes! I am drawing that “Kevin & Kell” comic. :)

Portraying racism in furry stories is in itself problematic, since racial traits are part of the reality in this fictional universe: Foxes are cunning, dogs are aggressive, rabbits are peaceful, and so on. Yet, I think Blacksad deals with this rather cleverly, by letting the racism be based solely on whether you have white fur, something which applies to such diverse animals as hares and polar bears.

A furry comic dealing with racism will of course be analyzed and the author’s ideological foundation scrutinized – and possibly furryously criticized, as is the case with review.

I think any kind of organized violence will naturally be geared towards a hateful black-white worldview, whatever its intentions. Although the police is a noble institution – it’s truly grand that we have people to deal robbers and thugs – the profession attracts the kind of people who fancy walking around in public with weapons and uniforms. When the US fought with Hitler, their racist propaganda was on the theme of ‘japs’ instead of Jews, and they forced 110.000 of their own citizens into internment camps. (Btw, a book I have yet to read: Considering Hate: Violence, Goodness, and Justice in American Culture and Politics)

With this in mind I thought BLACKSAD’s description of the aggressive Black Panthers was a fair depiction of how resistance to the enemies hate naturally becomes hateful. But it is a problem that this angle is the only description of black resistance. I understood the conflict as being based solely on Blacksad being pissed that someone on his own team could be so far of (“what happened to your brain”) rather than it being him defending the racial purity of his snout. But I dunno, I sort of think the review is right. I’m not 100% sure what my angle is on this.

But, just for fun and giggles, let’s imagine we published two different comics in one single publication, with the intention of nudging the reader to do a comparison: The first part of the publication consists of BLACKSAD: ARCTIC NATION – an anthropomorph depiction of the ’50s, with racism strongly in focus. The second part consists of a series of MICKEY MOUSE strips from the 50s – an anthropomorphic depiction of the 50s where the racism has consistently been redacted from history.

My point? To consciously avoid dealing with a particular subject, and thus removing said subject from your tales, is not a neutral act – on the contrary, doing so is a message from the author that he subscribe to the status quo. I think BLACKSAD wins over MICKEY MOUSE. Sure, BLACKSAD might be more or less crap in the way it deals with racism – but do you honestly try to tell me that furry stories that ignore the subject of racism altogether are doing a better job?

On the same note: DJANGO UNCHAINED was obviously analyzed and criticized for the way it dealt with slavery. But if Tarantino had instead made a “normal” western where he had erased slavery from the reality of the narrative, there was hardly anyone who had noticed.

Pingback: Tex Avery The First Bad Man Texts Police | Best Method to Last Longer in Bed