It doesn’t matter who the characters are in the 1989 film “Tetsuo: The Iron Man,” a brutal, seething, hurtling, cyber-mutant tone-poem directed by Shinya Tsukamoto. There are two men, both infected by a fetish for merging metal and flesh, bonded by a car accident. There is, temporarily, a woman, soon consumed by the wrath of a thick, grinding, motorized metal penis. Plot is spared, while there is no end of spawning microcircuitry, pounding mechanized rhythm, demonic cackling, and tortured erotic breathing. By the end of the film, one man declares to the other, “Our love can put an end to this whole fucking world.” It is a fairly realized vision of sadism– the key word being “vision.”

In Takashi Miike’s 1999 film “Audition,” more concessions are made to the demands of conventional cinema, and to worthy effect. The plot has a meaningful arc– a widowed movie director is convinced by his youthful son that he needs a new wife, and, by his friend and colleague, that he should find the ideal candidate by auditioning actresses for an essentially bogus role. Having followed his friend’s advice, he then ignores his further warnings when a breathtaking young woman auditions, and begins to occupy his thoughts. The romance first goes well, until the director reluctantly pulls back on advice from his colleague. But then, near the end of the film, things suddenly begin to go very badly. Flashbacks begin, a cackling demon appears in the person of the actress’ viciously abusive former ballet teacher, and our director ends up much like Tetsuo, in both of his bodies– shoved full of metal (long needles, in this case, with wires being employed to hack off his feet), and shuttling subconsciously between a variety of alternate nightmare realities.

Visual markers, from beer glasses to telephones to photos, pace out the slowly building dread in Audition, as the images of faces, cityscapes, and machinery escalate the hysteria in Tetsuo. The reason is that both movies are visual meditations, even if one employs stop-motion animation, with churning processed music and jump cuts, and the other uses long, still shots and a melancholy acoustic score. The plot in both cases is vengeance. As murky (and transparently irrelevant) as the plot is in Tetsuo, it is clear that the couple are punished for hitting the fetishist with their car (and then, J.G. Ballard- style, having sex in front of his crushed body). In Audition, as we eventually discover, the ballet teacher spent years training the actress, only to then physically and psychologically destroy her with sadistic sexual abuse. She has her just desserts with him, first severing his feet and eventually his head. But we also see her with a live body trapped in a sack, and then, in at least one of a couple competing reality threads at the end of the film, she ends up torturing the director, our protagonist.

The bodies of the director and the teacher merge in Audition as those of the driver and the victim merge in Tetsuo. They are sadistic, image-driven stories, and images exist to hybridize and proliferate. And yet, they are vengeance stories, supposedly following the plot logic of the slasher film, in which all brutality is punished– a logic that is not sadistic but masochistic. Nobody gets anything that’s not coming to them. This is the power of the rape-revenge film– in “I Spit on Your Grave,” to take an archetypal example, we are treated to a lengthy and nauseating rape scene, and then to the pleasure of seeing the rapists summarily slaughtered by the victim. In Audition, the ballet teacher gets his, and the director, when he becomes a victim, seems also to receive poetic justice in becoming an immobilized object, in recompense for treating the woman he acquired under false pretence like a commodity he could admire, customize, and ignore at his pleasure.

This strange dynamic, popularized in Hitchcock and then metastasized in the blockbuster action film, has been a way for the viewer to have the cake of violence and eat her moral turpitude as well. And, from Hitchcock to Lynch to Cameron, the viewer is, in some odd way and at some point, given the role of the director, the eye of the camera, which (pretty literally in the cyborgs of Terminator or Tetsuo), makes the pleasure monstrous and thus uncomfortable/ However, the discomfort of the monster becomes pleasurable when the monster is slain– as unresolved as this killing inevitably feels, in the ending as well as in all subsequent sequels. The problematic relationship between morality and pleasure, vengeance and forgiveness, is outlined with some profundity in these films, and then– left unresolved.

What is somewhat unique about Audition, however, is that the director is introduced as a thoroughly sympathetic protagonist from the very beginning. We see his warm, caring relationship with his son, his wistful love for his deceased wife, his dedication to his work, his thoughtful approach to decisions, his heartfelt fascination with the actress. And yet, what does it matter to her? He more or less picked her out like a mail-order bride, but without the decency to make his intentions clear from the outset. His obliviousness isn’t insignificant, but it may ultimately not be enough to separate him from the ballet teacher, who molds the actress to be his ideal vision, and then scars her so that she can never leave him.

Power operates through people, not in them. Whether a population is dispossessed by foreclosure or decimated by bombs, torn apart in civil war or religious conflict, the unending abundance in the midst of this competition for scarcity is the overflow of gleeful destruction, the cackle of the demon. When, with the Audition director, we lose control of the scopophilic machine that has started to enter us and cut us apart, we find that this machine was what we came to see, the flame that we flew to. What this film offers is not the ambiguous, tainted conquest that sullies the honest bloodthirst of the slasher genre. It offers endless defeat, in submission and in disintegration, which, as Simone Weil might assert, is one truth of force. And another, Tetsuo reminds us, is that force will, ecstatically and at any expense, feed itself forever.

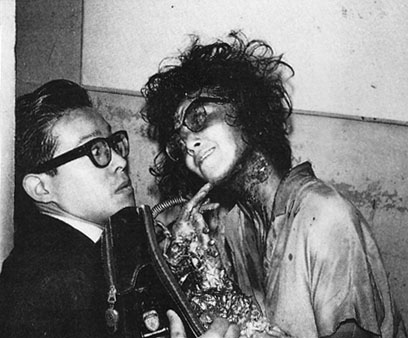

I think that scene of the woman in Tetsuo chasing the man in the subway one of the sexiest scenes in the movies, the way she gets wilder and her hair more crazy. Tetsuo 2 and 3 are disappointing in some ways but have amazing stuff in them, 3 in particular was unassured and awkward in the voice acting and some effects.

I finished the Tom Mes book a while ago and I cant remember enough to really discuss the themes of the Tetsuo films except for the general Tsukamoto theme of Tokyo and technology dehumanizing people.

Have you seen Tsukamoto’s newest: Kotoko. I think it is his best since Vital.

No I haven’t seen it. Thanks for the recommendation.

Yeah, both movies are extremely sexy. By “sadistic” I mean sadistically titillating.