Somewhere in the last thirty-five years, Heavy Metal has earned a reputation as a legendary magazine that printed the best in trippy[1] Eurocomics (the stoner teens of the 70s were apparently deemed too simple to understand the term BD[2]). Part of that came from canny marketing on the part of the editors; issue #2 had an ad proclaiming issue #1 was a collector’s item. A big part of the legend is that the artists they were publishing were legendary – Moebius, Druillet, Corben, Tardi, Chaland, Voss, et al. Of course, there is no easy way to contradict the legend – early Heavy Metal and Miracleman are two series with almost no available back issues in general circulation, which has had had a similar effect on the reputations of both titles.

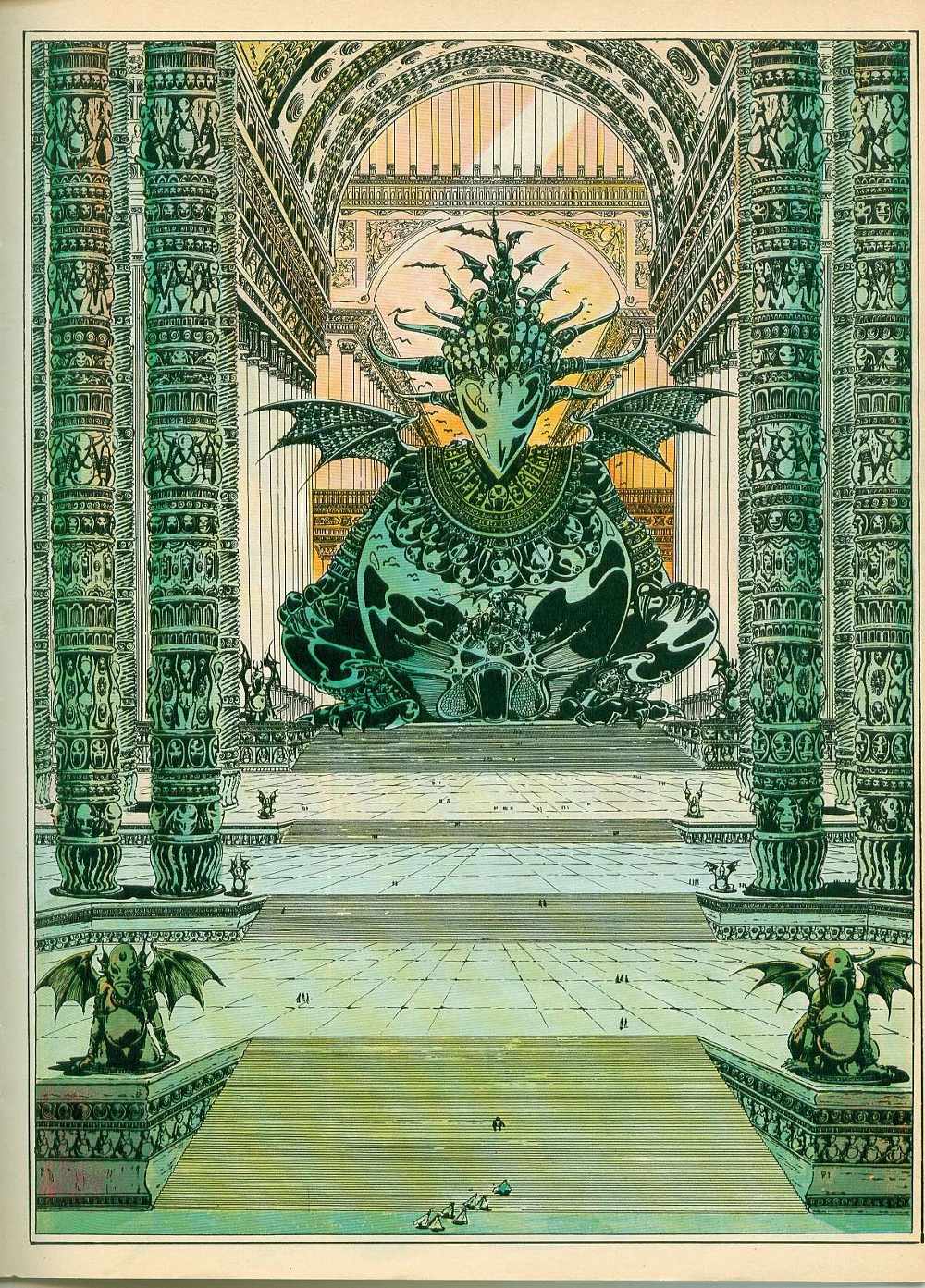

February 1978 – page 43 Urm by Druillet

When the opportunity arose to reread my father’s collection (he was a subscriber for the first twelve years of publication), I jumped at it. I’d read the run when I was in my early teens and don’t remember a lot of it. My delight soon turned to dust – I was appalled when I waded into the first two issues because the art is beautiful, but the stories are lacking. In fact, the word “stories” is generous. In some places, there is an utter lack of concern – bordering on outright disdain – for comprehensible narrative.

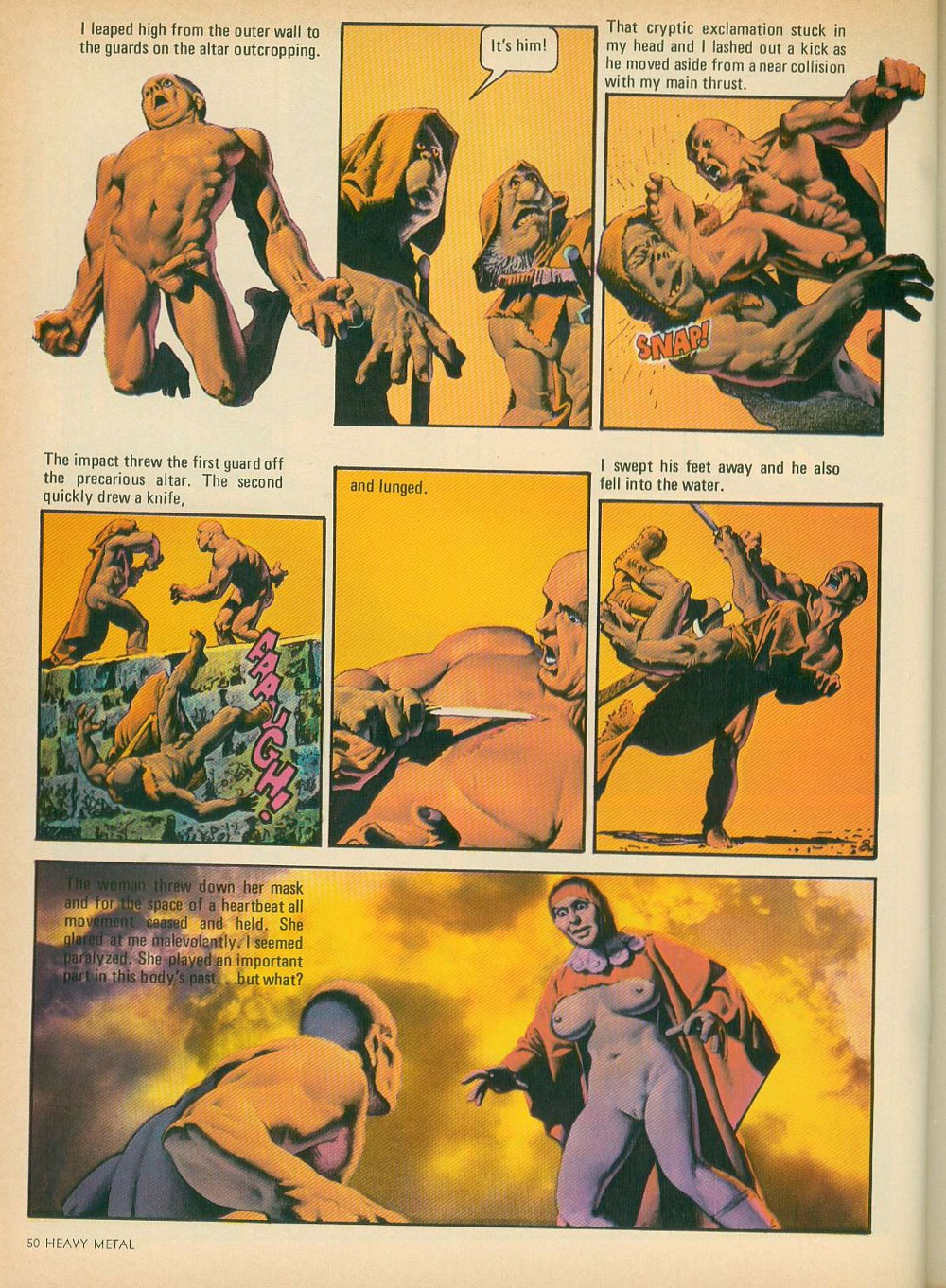

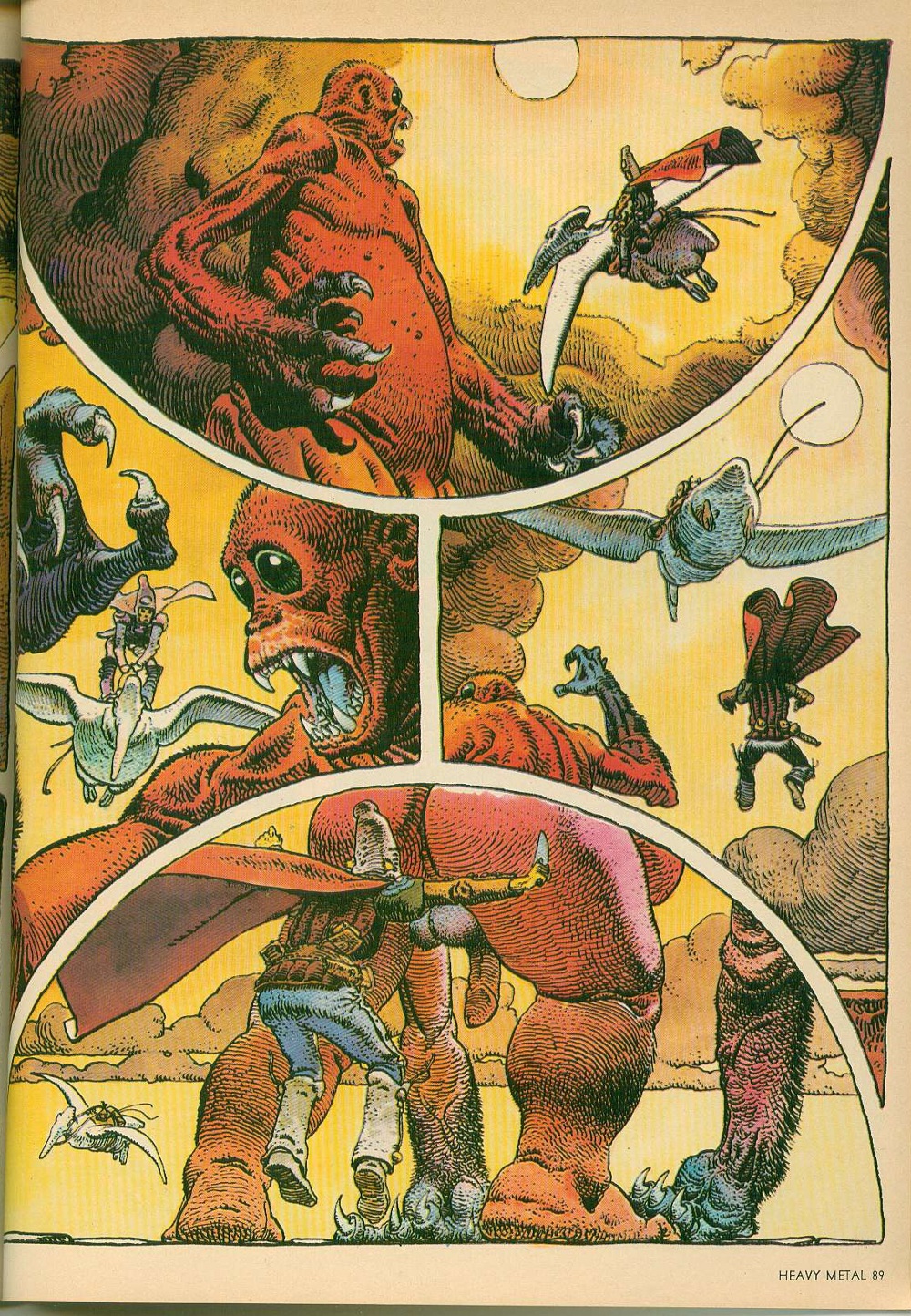

June 1977 – page 50 Den by Corben

The cognitive dissonance caused by the collision of the magazine’s reputation (especially the early issues, which are generally mentioned in terms of “when it was good”), and the actual work is jarring. It shouldn’t have come as a surprise – the fact that I’d forgotten a lot of it was a clue. But I had high hopes and the determination to look at each issue on its own merits. After a year of reading, I can say this: the issues from the 70s[3] are very problematic.

The abundance of breasts in the magazine has become somewhat of a running joke over the years, but the amount of rape (and stories where attempted rape drives the action) that appears in those first three years is something else entirely. I really didn’t keep track of how often it happens, but any number more than “none” is usually a bad sign. Tragically, it’s mostly used as just another plot point, with no mention or indication of the consequences. I’m clearly a bad person because I don’t consider the inclusion of rape themes in an anthology as an absolute show-stopper and kept reading.

To keep myself from screaming at some of the weaker pieces, it was important for me to keep in mind that Heavy Metal is very much a product of its time and had a very specific audience. The ideal reader would put Pink Floyd on the turntable, adjust his headphones, take a few bong hits and settle back into a beanbag chair and stare at the new issue for hours. Drug references abound. One of the early marketing taglines came from a reader’s letter “Heavy Metal is better than being stoned. Almost.” And in 1979, Job rolling papers became a regular advertiser.

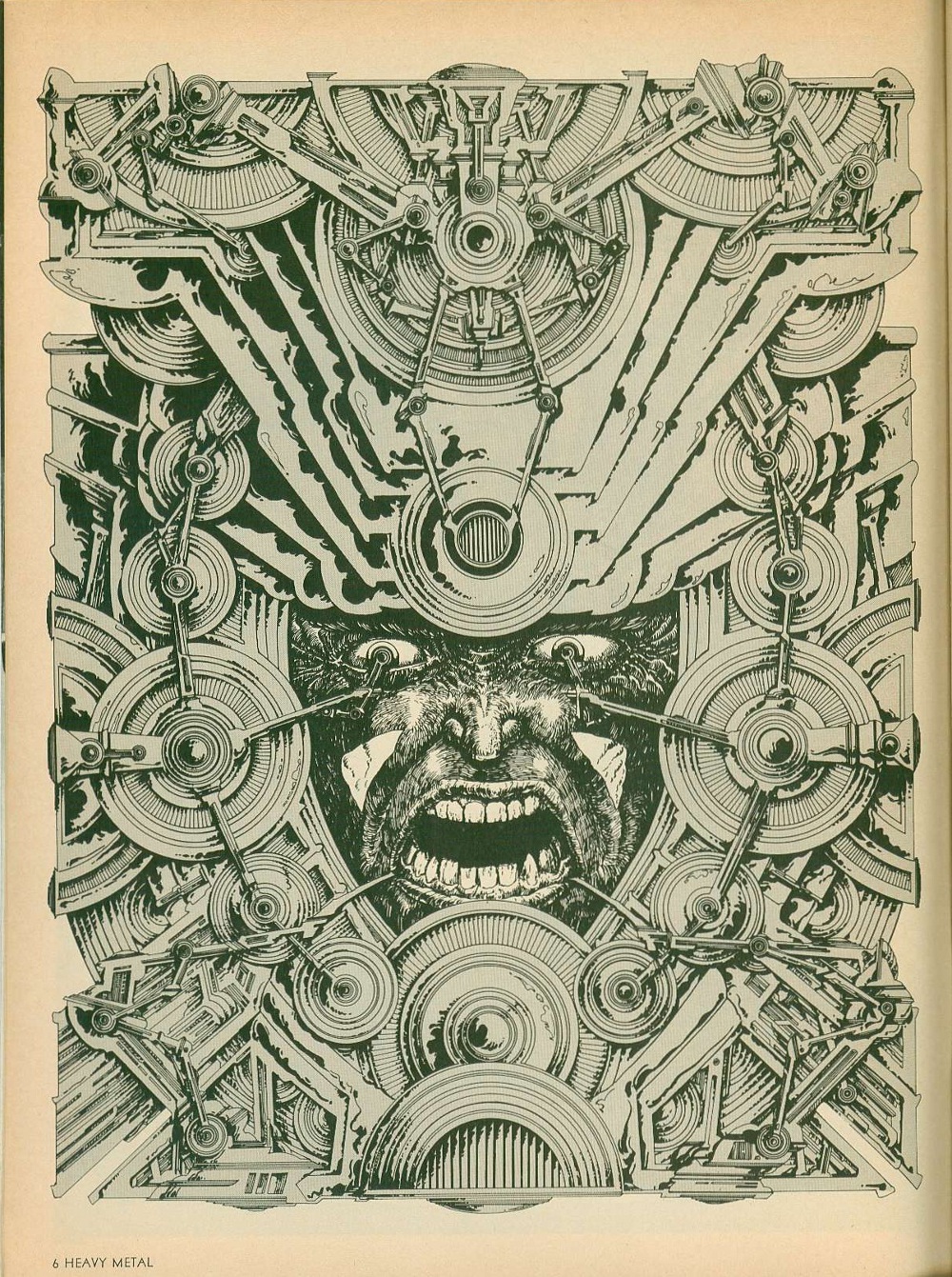

September 1979 – page 3 Job rolling paper ad

For their part, the creators were mostly European men with Old World attitudes towards women – the usual reaction towards Feminism was the inclusion of full-frontal male nudity, not to cut down on improbable breast-revealing costumes for queens who all seemed to live in tropical climates. (It is very obvious that Richard Corben and Russ Meyer would have had a lot to talk about.) These were comics by stoners who liked titties for stoners who liked titties.

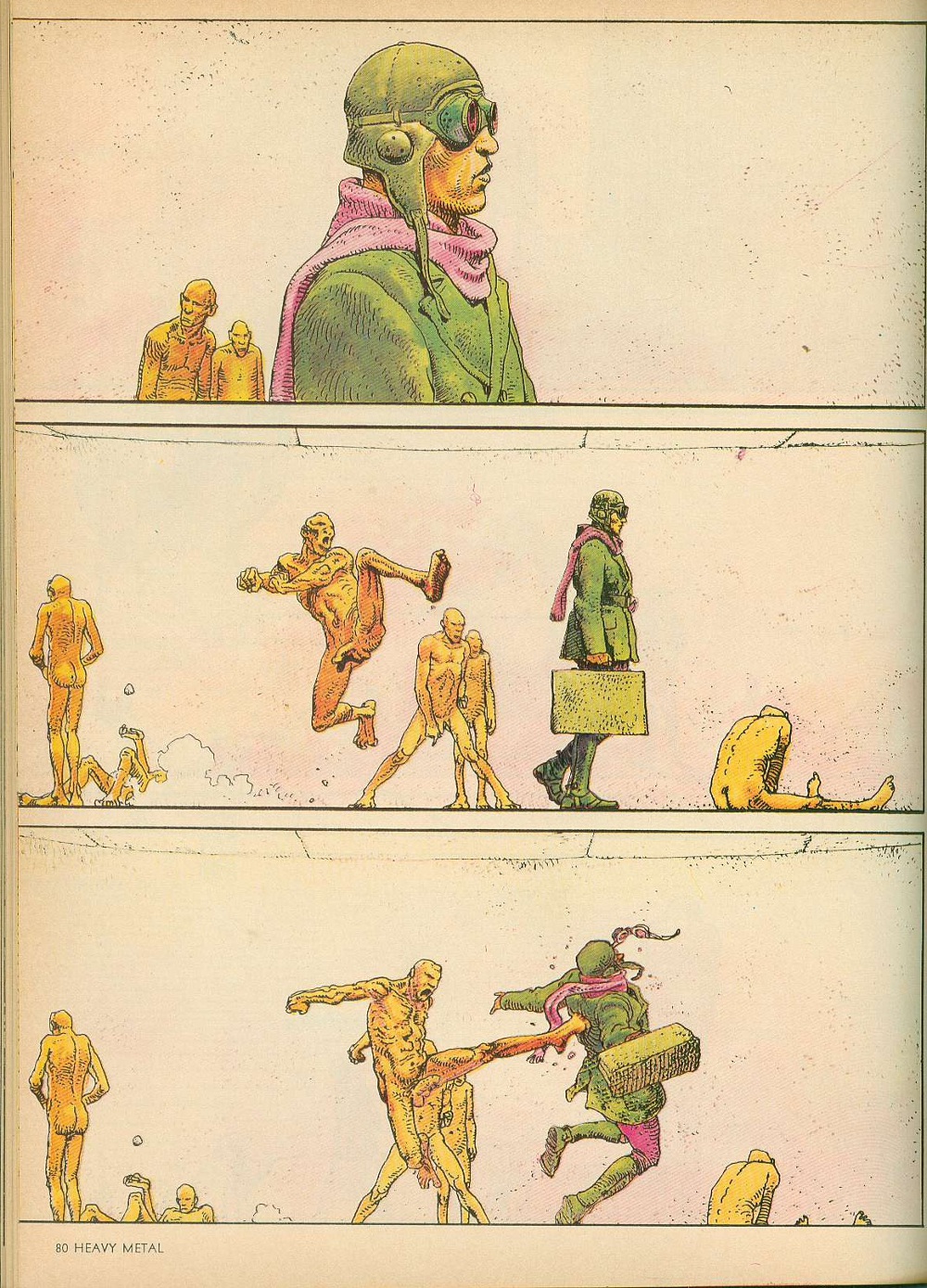

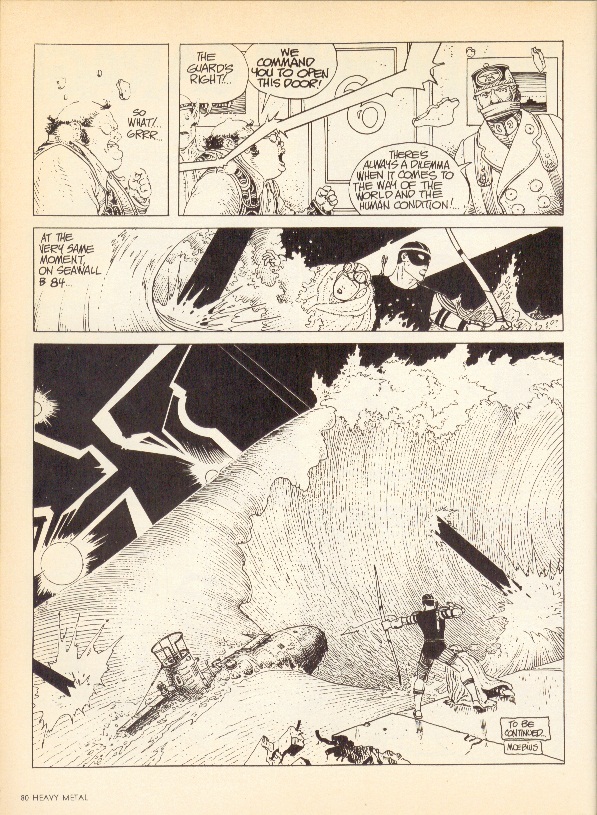

June 1977 – page 80 Harzak by Moebius

If that’s your thing, then this is the magazine for you. But if you are one of those heretics, like me, that wants actual stories with your sequential art, this is very hit or miss, with more many more misses than hits. One of the major issues in contemporary art comics (which arguably takes its aesthetic cues from Heavy Metal or what the creators think Heavy Metal represents, including the sex and drugs) is that the art is engaging and interesting, but has almost no narrative continuity from page to page or even panel to panel. The artists are having fun drawing interesting shit, which is fine. But a comic that is worth looking at once with little to no reread value is questionable at best. Unfortunately, that’s Heavy Metal in spades.

The stories that Moebius was cranking out in these early issues – Arzach[4] and The Airtight Garage – are beautiful works. He was very clearly exploring the limits of his artistic ability and the results speak for themselves. But they make very little sense. Arzach was the first major project that Moebius engaged in after working on Blueberry with Charlier for Pilote, and its wordless pages actually carry some narrative weight, but The Airtight Garage is like a kite without a string.

September 1979 – page 80 The Airtight Garage of Jerry Cornelius by Moebius

There are intrigues and airstrikes and assassinations and an entire sequence with an archer getting onto a submarine that look like they should be of some consequence. But the narrative stutters so much that the pieces never really come together and the revelations mean nothing. Moebius acknowledges this – one of the chapters is titled The Uptight Garbage of Moebius and a synopsis for another chapter mocks the narrative flailing. Towards the end, Moebius flat-out ignores any of the story he’s written so far and just goes for broke. The results are visually amazing, but severely flawed.

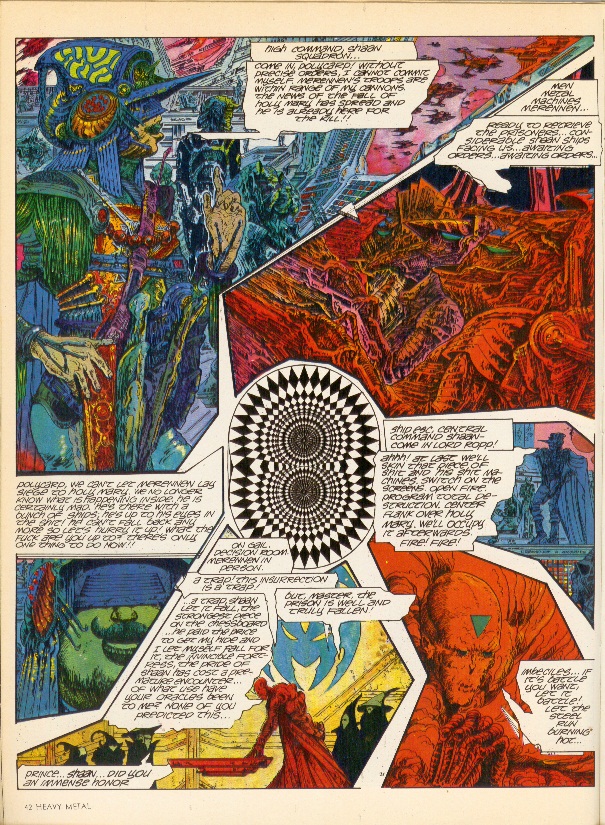

Druillet – one of the original co-Humanoids – is another case in point. His early black and white work is messy, but when he discovered color, it was like he leveled up. The color spreads from Ulm the Mad, Gail and Salammbo are amazing. He did interesting and innovative things with panel borders, incorporating photography into his art and even threw trippy optical illusion pieces into the mix. His design aesthetic owes a lot to Kirby, especially his spaceships and headgear, but it would take someone far more versed in the latter to really do a deep dive on that subject.

November 1978 – page 42 Gail by Druillet

One thing that Druillet could have completely left out of his later color work, though, is the words – they just get in the way. In some cases, they are lettered too small to be readable and in others, they just don’t make sense. Either way, they tend to slow down the story unnecessarily – especially the large captions that run to multiple paragraphs. It’s clear from his art that he wanted to produce epic works, but writing is not one of his core skill-sets.

It would be easy to lay the blame for these narrative inadequacies at the feet of poor translation, but the same issues crop up in works by English-speakers as well – Todd Klein, Steve Bissette, Rick Veitch and Charles Vess, I’m looking in your direction. And some of the best stories come from European sources – Jacques Tardi’s work Polonius stands out, as do several of Caza’s allegorical tales. And when these artists are working with honest-to-god writers – Dan O’Bannon/Moebius and Druillet/Picotto are good examples – they actually come out looking very good.

May 1977 – page 89 Arzach by Moebius

In the final examination, the art from those early years holds up really, really well. And if that’s what you’re looking for, these are great issues to track down (October of 1979 is probably the best from that period, in my opinion). But if you are one of those people who values actual story with your art, then you are going to be sorely disappointed. Obviously, the disconnect between story and art is something that the contemporary comics reader still has to grapple with and it’s fair to say that Heavy Metal is not where the trend started – it’s just the most obvious, most famous example.

Moebius and Druillet (among others) obviously put a lot of effort into their work. It seems like such a waste that they didn’t take that extra step to find a good writer to really make the work sing. And it’s not like they went out of their way to produce bad stories; they just aren’t good, which was so frustrating that it made me want to scream. As a result, they ended up producing really high-quality art comics at a time when the term didn’t exist.

When Moebius died, Neil Gaiman pointed out that The Airtight Garage was much better in French than it was in English because he had room to imagine how brilliant they were. Accordingly, my advice to young creators who are pining for these works is to go onto amazon.fr[5] and buy them in French, where they are easily available for reasonable prices. You’ll get the best part of the comics without having to put up with the sub-par quality of the writing. Plus, the French archival editions are usually very large, which lets the art breathe. In the unlikely event that these were actually published in English, the current trends tend to indicate that they’ll be shrunk down for some reason that makes no sense – which is another rant entirely.

[1] “I’d like to see an adult magazine that didn’t predominantly feature huge tits, spilled intestines or the sort of brain-damaged acid-casualty gibbering that Heavy Metal is so fond of.” Alan Moore, May 1981

[2] BD is short for Bandes dessinées, which is French for comics. BD:French::Manga:Japanese::Comics:English is the best way to think of it. People who know what to ask for will get much more out of their trips to Brussels and Paris.

[3] The issues from 1977 through 1979 serve as a good scope for this article for two reasons. First, Ted White became the editor in December of 1979, visibly changing the text/art ratio of the individual issues. Second, I’m only halfway through 1980 in my reread and can’t speak definitively about anything past that.

[4] Also spelled Harzak, Arzak, Harzac, Harzakc and Harzack

[5] It’s exactly the same site design as amazon.com, so the language barrier isn’t actually that big of an issue

I don’t disagree that most of the material, and the magazine as a whole, is overrated, but your criticism is just a retread of the facile “good art, bad story” that has haunted comics criticism for so long. It fails entirely to take into consideration the story told by the images, never mind the non-narrative aspects of same. I agree that a lot of this material is borderline unreadable, but that’s not an inherent fault of the approach taken by many of these artists. Your criticism of Arzak and The Hermetic Garage, for example, seems to me entirely to miss the point.

I’m sorry. I’m not sure what I point I missed. I’m genuinely curious what approach these artists were taking that I should be taking into consideration. Your response makes me think that there’s something obvious that I missed.

In the piece, I acknowledge that Arzach has some narrative weight – the page I included shows off Moebius’s ability to show action – but when all is said and done, the various Arzach pieces are still nothing more than vingettes. And some really make no sense whatsoever as a whole.

If anything, I think the “good art, bad story” throughline has been haunting comics for a long time, not necessarily just comics criticism. As long as people are willing to argue that comics without story have value, nobody will ever really make an effort to correct the issue.

Well, you’re certainly not wrong that there’s a lot of bad writing and storytelling in comics (as well as tons of bad art). But my problem with the kind of criticism that uncritically separates ‘art’ and ‘story/writing’ is that it misses essential aspects of comics as a visual medium. The “writing” is also in the images and their structuring, plus there are comics that don’t — and shouldn’t be expected to — place as much emphasis on straight narrative as others, such as Moebius’ and Druillet’s works of the seventies.

I don’t see why that is necessarily a problem and disagree with the commonly-held notion that comics are essentially about storytelling. I expect that you wouldn’t apply the same criteria to literature, where “vignettes” (poems?) clearly are prefectly acceptable, as are works that eschew storytelling or linearity/consistency of plotting — most of modernist literature, for example.

As for why this would apply to much of Moebius’ work of this period, especially The Hermetic Garage, I’ve tried to work my way through a bit it in this essay.

I had a torrent of the (almost) full run awhile back. Went through it and deleted it all except a very few works that I saved separately. Looking at my harddrive it appears to have only been Crepax’s work (Valentina stories) and Jean Teule’s Daughters of the Night (for the photographic aspect). Though I guess I am far from the ideal reader for this stuff.

Ah. I see what you’re saying. And, to a certain extent, I agree with your basic premise – there is not, and should not be, a divide between art and storytelling in comics. They are one and the same and should be addressed at the same time.

There is a saying: “most writers think they can’t draw the same way that most artists think they can write” which is another way of saying “it’s easier to spot bad art than it is to spot bad writing.” Bad storytelling is not an issue that is unique to comics – all forms of narrative art (poetry, films, novels, etc) have exactly the same issue.

The argument that I hear you making (and please, correct me if I’m wrong) is that comics is not necessarily a narrative artform. That’s an argument that gets right down into weeds of how the source code of the artform works and operates. It’s absolutely a discussion worth having, but my bottom line up front is that comics is an inherently narrative artform – one that can be subverted and made to do things that it wasn’t meant to do, from time to time.

But you seem to be arguing that Moebius and Druillet were not necessarily trying to write stories, which doesn’t actually make sense. Why else would Druillet attempt to adapt a novel by Flaubert if he wasn’t trying to write a story? It’s obvious that the Airtight Garage was an attempt to write a SF action serial, but it just wasn’t very well executed.

Heavy Metal was mostly filled with irredeemable crap but it did give the English-speaking world stuff by the Schuiten Brothers (Nogegon), the butchered Breccia Dunwich Horror, and De Crecy’s Foligatto (which is sort of entertaining I think) etc. etc.. And I suppose the Crepax stuff which Derik mentions I suppose.

And preferring Polonius over The Airtight Garage is totally nuts – but that’s perfectly acceptable on HU. While it might be damning with faint praise, I’d say The Airtight Garage is probably one of the top 5 SF comics ever. And that’s purely based on the way it’s written. I honestly can’t think of a single American SF comic which even rates mentioning. It’s certainly way better than any Gaiman comic I’ve read. I could change my mind once I’ve reread it of course…

The Airtight Garage wasn’t an attempt to write an SF action serial like Flash Gordon, Buck Rogers, Dan Dare, or The Trigan Empire. That’s for certain.

I probably am talking out of my ass here but I guess the point was having no point.

I really don’t know about Druillet, his early stuff seems Moorecock infused SF/F that confuses baroque pages with good or inspiring storytelling.

But regarding Moebius, at least The Hermetic Garage, the intention was to create this narrative mess that stumbles upon itself, that leads itself into corners only to find creative ways to escape from them. I guess it was more akin to a piece of performance art from a certain point of view. If there are problems, they stem from this creative philosophy and not from Moebius’ (lack of)skills as a “writer”.

And the Arzach strips are really mostly great exercises in purely graphic storytelling, with weird designs, creatures, and locations; I guess that they are more of a reaction to the way mainstream french action comics worked, with loads of text and a lot of tiny panels that strive to depict some kind of realism(and reality).

While I don’t think comics are essentially a narrative art, I do think narrative is essential to the vast majority of comics. But that doesn’t preclude narratives that unfold in non-linear, disjunctive, stream-of-consciousness ways, such as The Hermetic Garage, nor does it devalue comics that work in more lyrical fashion, such as Arzak. It’s all narrative (and masterfully done, in my book), just not in the way you’re asking for in the essay.

Yes, in comics the drawings are also the story. And yes, Moebius and Druillet and Corben were skilled. But if the stories are unreadable doesn’t that mean that the drawings aren’t that great after all? I, for one, view them as the pompier artists of comics.

The “Airtight Garage” is an exception though. It was clearly an experiment: Moebius said that, I’m paraphrasing, a story doesn’t need to be like a house, with a door and windows to look at the trees and a chimney, etc… He wanted to do a story like an elephant, like a wheat field or a match. I don’t like it either, but maybe that’s because I’m not interested in sci-fi tropes at all. On the other hand one could say, with Rhodes above, that while trying to subvert traditional narrative, he simply destroyed it. Which is not a problem in my book, it’s just that instead of an elephant he created an amoeba.

Talking about pompier art. Here’s one for Noah.

Heh. I think Marston might have liked that one. Especially with the boot off; he approved of that sort of thing.

What is the ideal that you’re holding these comics up against? That’s probably the thing I’m not understanding. What are some examples of sci-fi comics that are in your eye what Moebius, Corben, and Druillet should have strived for?

One of my very favorite Moebius comics has no words in it, and is just a guy sitting in the desert while shit happens all around him. Is that a failure by your rubric?

“What is the ideal that you’re holding these comics up against.”

I can’t speak for the others, but I always use the Gold Key Star Trek comics as my unit of measure.

” What are some examples of sci-fi comics that are in your eye what Moebius, Corben, and Druillet should have strived for?”

Like Suat says the problem is that there aren’t any good ones. Or at least not that many. Think manga instead.

Man, that June 1977 Druillet page sure gives Kirby a run for his money, doesn’t it?

“..But they make very little sense…”

I could see where you could be thrown off “The Airtight Garage / Le Garage Hermetique.” There’s nothing in the story that lets you know Giraud was in a stream of consciousnes mode. But Arzach is really straightforward. Yes, its dreamlike and not especially weighty but it doesn’t throw the curveballs that the other story does.

“Second, I’m only halfway through 1980 in my reread and can’t speak definitively about anything past that.”

It’s more of the same. Like the other said, once in a while you’d find something interesting. But the rest….

Oh, the very earliest issues of Heavy Metal may be hard to find, but all the rest are easily available online. With Miracleman, the earliest issues are dirt cheap and plentiful; it’s the later issues that are tough to find.

“I agree that a lot of this material is borderline unreadable, but that’s not an inherent fault of the approach taken by many of these artists. ”

If a story is unreadable, how is not that fault of the artist?

“…how is that not fault of the artist?”

Yeah, well… At least I like one of Druillet’s and Moebius’ stories. The only science fiction that I really like in comics is HP by Kostandi and Buzzelli and Aunoa by Buzzelli because there are plenty of politics in those stories.

Rereading my post I asked myself: how could I forget the truly memorable El Eternauta?

I think Moto Hagio’s sci-fi comics are very good (those in AA’ especially, though I think that’s now unfortunately out of print.)

Alan Moore/Ian Gibson’s Halo Jones also holds up surprisingly well, I’d argue. It’s very politically engaged. Have you read that Domingos?

Nope.

Oh also I completely disagree that these stories are unreadable. But I accept that it’s perfectly valid that someone could read one of these stories and completely not understand them. People have different tastes. There’s nothing objectively wrong with the narrative approaches taken by Druillet and Moebius in their work. What is being expressed here is a subjective taste that is somewhat masked behind the guise of objective criticism.

I think by taking on ALL Heavy Metal stories, rather than focusing in on just one, and breaking it apart to show what you mean by saying that they are narratively broken–you’ve given us little more than your opinion that comics that other people like, you don’t like. Which is fine. But it is not an accepted viewpoint that Moebius for instance lacks storytelling chops. And if you’re going to go at one of the kings of comics, you best not miss.

And I think you’ve missed with this piece. I would be interested in a follow up piece where you took on Airtight Garage or Arzach and really did a close study of the work, to discover both what Moebius was trying to accomplish in the work, and why you either think that failed–or why it produced such a cognitive dissonance for yourself.

Also the notion that there are no good sci-fi comics is another one that I disagree with. But I understand where if you thought that Moebius wasn’t a good storyteller–you would also think there aren’t good sci-fi comics–because Moebius is responsible for most of the great sci-fi comics.

Also the weird separation where manga are considered not comics will never cease to blow my mind. If there are great sci-fi manga, then there are great sci-fi comics. Manga just refers to japanese comics. I mean we’re talking about Moebius who makes french comics, and then turning around and saying well japanese comics don’t count as comics. It’s completely bizarre.

“Planetes” is another sci-fi manga with an excellent reputation. And Hisashi Sakaguchi’s “Version.” It’s just very hard to think of American examples where the story is equal to the artwork.

Contra to what someone else said last month, it’s hard to look at that Corben page at top and not think his work is adolescent.

Your comment about manga seems like it comes completely out of left field, Sarah. One of the things I thought I made clear in the piece is that BD, manga and comics are all more or less the same thing, just with different labels, depending on the language that appears on the page. The reason I didn’t really bring manga into the discussion is that, well, I was talking about my reaction to early issues of Heavy Metal – issues where the manga content is exactly zero.

I’m also baffled as to how this could be considered anything but a subjective piece – it’s couched in personal experience and reaction, based on the reputation that I felt that Heavy Metal has accumulated.

And where, exactly, did I indicate that there are no good SF comics? One of the comics I specifically indicated was good was the work that Moebius did with Dan O’Bannion – a SF comic.

I guess I could understand why this was read as “taking a run at Moebius,” even though it wasn’t meant to be. I was trying to discuss the reaction to the overall reputation of the magazine and Moebius and Druillet are both easy targets and foundations of that reputation. So hey, fair cop on that point.

The manga comment was in reference to Steven Samuels who said there aren’t any good sci-fi comics, and that there were instead good sci-fi manga.

Ah. Well, that’s just a stupid thing for him to say.

Aren’t you two overreacting? I don’t agree with the distinction myself, but it’s fairly common. If you are going to say that those who use it are saying stupid things, you’re saying that about a whole lot of people.

I think this conversation has gotten a little confused? Steven was saying (a little hyperbolically, as he acknowledged) that there aren’t a lot of good Western sci-fi comics. He was saying that sci-fi manga tends to be better. Sarah disagreed that Western sci-fi is quite so much of a wasteland. RM Rhodes (after a bit of confusion) agreed with her. Domingos brings up the issue of whether manga and comics are really separable — which is a fine question, but not necessarily what RM and Sarah were arguing about.

So…I don’t think anyone’s said anything stupid? For whatever reason, the thread just seems to have gotten a bit garbled, for whatever reason.

I realized as I hit send that it’s possible that Steven was using comics/manga in the sense of “they are the same thing, but the distinction is the language they are printed in: If they are printed in Japanese, they’re Manga – if they were printed in English, they’d be comics – if they were French, they’d be BD.” But then he’d be arguing that there are no good English language SF comics, which ignores American Flagg, Give Me Liberty, Supergods, DMZ, BPRD, Y: the Last Man, Bodyworld, Atomic Robo, Orbiter, Xtinct, Miracleman and/or Top Ten. I’d give him the benefit of the doubt on the first part, but not on the second part. It’s an overly broad statement and easily refuted.

Stevem re: this:

“I agree that a lot of this material is borderline unreadable, but that’s not an inherent fault of the approach taken by many of these artists. ”

If a story is unreadable, how is not that fault of the artist?

What I was saying the the approach taken by a Moebius in The Airtight Garage, or a Druillet in Ulm, is not inherently a wrong or bad one, just because it isn’t linear or coherent. That a lot of the other comics in Heavy Metal are borderline unreadable is just because they’re bad.

I haven’t read all of those…but noen of the ones I have make a good case. Y: The Last Man is really not very good. Top Ten is a superhero comic; so’s Miracleman.

Anyway, if you look back, Steven said there were hardly any good english-language sf comics, not that there were none.

If those are the good ones I can’t even imagine the bad ones.

Brandon Graham (along with various artists) has a run on Prophet (yes, the Rob Liefeld character) going on right now that’s a pretty damn good example of huge-scale sci-fi, spanning mostly-dead planets and galaxies centuries after a massive war has taken place. I’m really digging it.

For other American/English language sci-fi comics, there’s Transmetropolitan (more of a political series than a sci-fi one, but it’s Warren Ellis, so there’s plenty of future tech and society stuff), and Carla Speed McNeil’s Finder (which I’d argue is pretty amazingly good, deserving of being listed in a top 5 or whatever). And maybe Nexus? I haven’t read enough of it to know whether it’s considered more of a superhero thing. And did anybody mention Judge Dredd? I haven’t read much of it, but at least certain portions of it are pretty well-regarded.

Oh yeah, what about Adam Warren? His current series, Empowered, is a superhero comic, but he also did Dirty Pair, which is pretty solid sci-fi action.

If we’re talking 2000AD sci-fi–the Pat Mills/Simon Bisley Bad Company Black Hole story is very excellent. There is a lot of 2000AD that I’m going back to these days which hasn’t aged much at all. Really stunning art with surprisingly enjoyable writing.

Matthias: I find your authorial intent argument very funny. But it’s so ridiculous that I’ll let you have it on audacity alone.

Noah: I thought we’d established that my standards of good vs bad are not the same as the rest of the group? Or did I read that wrong? Also, I would argue that a lot of superhero work has SFnal elements to it. But that depends on how heavily you want to draw genre boundaries, which is, again, subjective.

Matthew: I cannot believe that I forgot Transmetropolitan and Finder. And I was trying to think of a good Alan Moore title, which is how I landed on Top Ten and Miracleman. DR and Quinch, maybe?

So they didn’t run Chantal Montellier’s Shelter in 1979? Nicole Claveloux wasn’t printed in those early issues at all?

Conquering Armies by Dionnet & Gal is also missing in my opinion: http://www.savagecritic.com/reviews/old-english-3/

RM, I don’t understand? I merely questioned your seeming assertion that any comic that doesn’t adhere to consistency and linearity of plotting is a bad one.

I don’t think the comics I mentioned are “unreadable”, they’re just not Tintin, you know? I actually find most of classic Moebius perfectly readable, as long as one doesn¨t expect Asterix. I’ll grant that Druillet’s work in the same period is pretty unreadable if what you’re looking for is tight plotting, fluid prose, but there are different ways to make comics, and those ones have lots of other things going for them.

But I’m repeating myself. What’s ridiculous is that you apparently refuse to actually read what I write.

RM, I think Suat was just saying that it’s fine to have different opinions; my tastes are pretty different from Matthias’, and his are pretty different from Suat’s…and so forth.

I don’t think I’ve ever read any Moebius or Heavy Metal, believe it or not…but I don’t think Matthias’ argument is about authorial intent? His point is that you can have trippy, spaced-out, not particularly linear narratives, and those aren’t necessarily “bad” writing. It’s like saying that Tarkovsky is a bad filmmaker because the pacing is slow, or that John Cage is a bad musician because there aren’t catchy tunes, or (maybe more closely) that William Burroughs is a lousy writer because there’s not much plot.

Again, that’s not to say that Moebius is actually a good writer — or even that William Burroughs is (I can’t stand him myself.) But I think Matthias’ point is that a clear linear narrative doesn’t have to be the only standard of good writing available. Evocative set pieces (for example) might also be meaningful or worthwhile.

Matthias, you crack me up. Where I work, it’s an accepted best practice to take a victory when it is explicitly handed to you and not quibble about how you got it. But I get it – I’m the new guy and you want to rub your victory in my face by making me demonstrate my reading comprehension skills. :)

So here goes: your argument boils down to the fact that Moebius and Druillet totally meant to eschew linear narrative and other plot-like trappings, not because they were bad writers per se, but because they were experimenting with the artform. It was the intention of these creators (authors, if you will) to not worry about these kinds of things when they made these works. It was absolutely their authorial intent to not have their work be judged on the same criteria that we would judge, say, Asterix. Did I get that right?

I have a rebuttal to the argument, but I want to make sure I understand exactly where you are coming from before I present it.

I think The Airtight Garage can be usefully compared with Naked Lunch (though the former is considerably more playful and interested in stylistic variation). Which means Noah is likely to detest it.

RM: “– it’s couched in personal experience and reaction, based on the reputation that I felt that Heavy Metal has accumulated.”

Heavy Metal has/had an awful awful reputation which has only grown worse with the years with the proliferation of T/A under the Kevin Eastman regime. No one reads it and hardly anyone is encouraged to read it. It was utterly despised by the TCJ crowd back in the day. This means it actually needs to be rehabilitated (in parts; which Jog frequently does for example) more than trampled on.

Also, American Flagg is a good choice for one of the best American SF comics ever. But Give Me Liberty and Y: The Last Man are both so awful I’m shocked that you even brought them up. It’s like Noah and his Ariel Schrag is better than Krazy Kat/L+R/Chris Ware thing :P

Oliver R.: I actually sort of like the Zha/Claveloux stories in the early HM myself.

Noah, I actually think there’s a distinct difference between being a good writer and being a good storyteller – about the same difference between being a good cartoonist and being a good storyteller. And you’re right – it is entirely possible that Matthias is not presenting an authorial/creator intent argument; I have attempted to clarify this before pressing onward. (Tongue planted firmly in cheek, admittedly.)

In all seriousness, though, I think there’s value in discussing whether comics are an inherently narrative artform or not. I argue that it is. How much of that point of view is based on my personal experiences as a storyteller is up for debate.

It follows that if they are an inherently narrative artform, then evaluating comics on the criteria of “did it tell a coherent story or not?” is perfectly valid. If not, then I’d be interested to see what other kinds of criteria would be applicable.

But the fact remains that I addressed the material in Heavy Metal from the subjective viewpoint of “I expect comics to be a narrative artform” and that’s how I judged the works I encountered. Maybe I should have led with that statement; I thought it was a default assumption.

RM…we have new folks here all the time; there’s no initiation right, truly. You presented a fairly aggressive argument in your post. Which is fine (good even!) but it means you’re going to get some pushback.

It sounds like Matthias and you actually agree about much of Heavy Metal. He just thinks Moebius and Druillet are doing a bit more than you’re giving them credit for.

Ah…just read your last comment, RM.

I don’t necessarily think of comics as inherently narrative. Obviously the artform has historically been mostly narrative. There are other possibilities though…for instance Andrei Molotiu’s Abstract Comics anthology (in which I was lucky enough to have a piece, actually.) Or the work of folks like Jason Overby and Warren Craghead, which sometimes use elements of narrative, but aren’t actually narrative per se.

Suat, is Moebius usefully thought of as a Beat?

Nope or at least I can’t see it. He’s dabbled in underground-ish work and some fantasy inspired autobio but that’s about it. And while he’s been associated with weirdos like Jodorowsky, he seems too well adjusted (and devoted to commercial genres) to be lumped in that group.

Mahendra Singh has a series of posts on art of The Airtight Garage. Cartoonists rarely try multiple variations in styles in a single work but this is a pretty good example and presumably something to do with the stream of consciousness/”improvisational” qualities of the comic.

I don’t really see the Burroughs/Naked Lunch, Moebius comparison. Though I enjoy both greatly. I don’t know that there are many useful comparisons to moebius. He was very much cut from his own mold, and though many have tried to duplicate him as the years have past–none have really succeeded. Burroughs I think you can make a ready comparison to the work of Gertrude Stein.

Gertrude Stein would be another example of a great writer who has eschewed linear narrative and traditional plot structures with great success. If Linear narrative and traditional plot structures are your thing then you’d arrive at some weird conclusions in art, where you’d say that John Grisham is a better writer than Stein or Burroughs. Or that Spielberg is a greater director than Tarkovsky or Bunuel.

Yes. Sarah and Noah have pretty much explained what I was trying to say better than I could. I’m not talking about authorial intent per se — though at least in the case of Moebius and the Garage, what I’m saying dovetails with his stated intent — merely that your criteria for judging some of the Metal comics, RM, are off.

Also, what’s up with the snark? I tried engaging your essay in a critical, but collegial manner and what I get in return are peeved insults and baseless accusations about my, ahem, authorial intent (“new guy-old guy”, yadayada). Doesn’t exactly motivate dialogue.

As the only contributor to this thread who bought Metal Hurlant from its first issue to its demise, I have some thoughts to contribute.

Metal Hurlant was not launched as a riposte to Rné Goscinny or to Pilote magazine. It had originally been announced as one of a group of new magazines to be published by Les Editions du Fromage (sic), the publishing house for L’Echo des Savanes, the pioneering French mainstream-distributed “underground” raunchy sex ‘n satire mag by Gotlib, Mandryka and Brétécher that was a surprise hit in the early ’70s.

None of the announced magazines were published, apart from Métal Hurlant which was put out by an entirely new entity, Les Humanoïdes Associés.

Back to Moebius: ‘Le Garage Hermétique de Jerry Cornelius’ was designed from the beginning as an improvisational riff from issue to issue…much like the riffing of Charlie Parker or that other early ’70s mainstay, the 10 minute drum solo (think Ginger Baker.) There is legitimacy in improvisation…the theatre of the time was rife with it and was truly enriched by it, as witnessed by the Living Theatre, the Théatre du Soleil, Grotowsky’s Theatre of Poverty, or even the comedians of Chicago’s Second City. (Are they still around, Noah?)

Comics are bound to conventions and expectations of genre; the wonderfully liberating pleasure we got from Garage was the fun of not knowing, issue to issue, what the hell was going to happen — while secure in the hands of a master.

————————-

RM Rhodes says:

And when these artists are working with honest-to-god writers – Dan O’Bannon/Moebius and Druillet/Picotto are good examples – they actually come out looking very good.

————————

Um, re the Dan O’Bannon/Moebius pairing, are you referring to “The Long Tomorrow”? Because it was a routine “hard-boiled dick” story with a typical noir twist at the end:

(Some NSFW) http://kipplezone.tripod.com/id53.html

————————

Domingos Isabelinho says:

… At least I like one of Druillet’s and Moebius’ stories. [ http://thecribsheet-isabelinho.blogspot.pt/2008/12/philippe-druillets-and-moebius-approche.html ] The only science fiction that I really like in comics is HP by Kostandi and Buzzelli and Aunoa by Buzzelli because there are plenty of politics in those stories.

————————-

Why, nothing like adding politics to make a creative work worthwhile! If I had to guess, it would have been obvious you’d only find Moebius’ “White Nightmare” worthwhile. (A bunch of French racists attempt to run down and beat up an Arab immigrant.) Quite well done, the arguing among the racists convincing in its spittle-flying unpleasantness:

http://glad-you-asked.blogspot.com/2009/12/white-nightmare.html

But, all the rest of Moebius is worthless, then? Personally, I can’t appreciate the art in his “Lt. Blueberry” Westerns; masterfully done, but too uptight for my tastes. (It was the surrealists that first awakened my excitement about and appreciation of the visual arts.)

From that link to Domingos’ blog:

———————–

The only genre that I hate more than science fiction is sword and sorcery fantasy. It seems to me that it’s pretty dumb to hate a whole genre, though. I can think of two reasons why this is so: 1) it all depends on what we mean when we say the word “genre” (genre paintings, for instance, are representations of scenes from everyday life; obviously, I would never be against that)…

———————–

(Emphases added)

In all fairness…

A great photojournalist, Margaret Bourke-White, was fond of this quote from Francis Bacon: “The contemplation of things as they are without error without or confusion without substitution or imposture is in itself a nobler thing than a whole harvest of inventions.” ( Much more wisdom at http://www.sirbacon.org/links/baconquotes.html )

And no less an SF writer than J.G, Ballard stated, “Earth is the last alien planet.”

Still, can’t “representations of scenes from everyday life” be mediocre? Fail to stir the heart and imagination?

And there are some of us whose tastes — sorry! — prefer something more exotic, strange than this visual meat-and-potatoes cuisine.

And is not a considerable part of the worth of “Little Nemo in Slumberland” and “Krazy Kat” the not-exactly “everyday life” drawings and situations?

———————–

Matthias Wivel says:

“I agree that a lot of this material is borderline unreadable, but that’s not an inherent fault of the approach taken by many of these artists. ”

If a story is unreadable, how is not that fault of the artist?

————————

That’s like saying if a writer provides idiotic lines of dialogue, and even a great actor’s reading can’t prevent the audience from laughing, “how is not that fault of the actor?”

————————-

That a lot of the other comics in Heavy Metal are borderline unreadable is just because they’re bad.

————————-

If you’re focusing on and demanding a logically-unfolding plot, believable characterizations, deftly witty and intelligent dialogue, expecting original and imaginative concepts, intellectual depth, certainly most are “unreadable.”

But there another kind of reading in comics, focusing on the visuals; and by this approach, HM stories in their heyday were not only routinely readable, but a tasty feast indeed.

However, a mediocre script serves to provide a springboard for the visuals; which to me and surely many others are by far the biggest pleasure from “Heavy Metal.”

Imaginatively visualized characters, gadgets, and exotic settings; visual storytelling that’s effective, striking, dramatic; bizarre creatures; those give an aesthetic pleasure in its own right.

As stated on another HU thread…

————————

Charles Reece says:

… I don’t have a problem with eye candy. A well-crafted thing is a well-crafted thing. I also can appreciate the aesthetics of action/violence — few people do it really well, so why is that less important than depicting relationships, or whatever?

————————–

…Who says we cannot greatly value certain characteristics of a work of art, dismiss others?

For instance, I’m told that in opera, the lines being so bombastically sung, making tears stream from the audience’s eyes, can be utter banalities like “Open the…window!” It would probably take a Domingos to dismiss opera aficionados as lowbrow fanboys, yet they’re universally considered an erudite, sophisticated bunch.

So if in opera the characters are two-dimensional, the plot machinations ludicrous, the wording of the lyrics banal…

…are not opera audiences then appreciating the “eye candy” of lavish sets and costumes, “ear candy” of glorious music and singing?

With the insipid characters and narratives mere raison d’êtres for that which delights the eye and ear?

Likewise, one can exceedingly appreciate Kirby’s visual artistry, considering similarly the stories as raison d’êtres for the creation of powerfully kinetic action scenes…

(Speaking of opera, those Druillet “spectacle” scenes from “Salammbo” [ https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/10/salammbo/ ] would make great opera settings; lavish, overwrought, mostly static backdrops for singers to boom out arias. [And “Salammbo” was itself “operatized…])

Mike, Druillet actually designed the sets for a proposed movie trilogy of Wagner’s Ring.

Can you imagine a Druillet-designed ‘Ride of the Valkyries’?

Druillet also collaborated with Rolf Liebermann and Hubert Camerlo on ‘Wagner Space Opera’ in the Opera of Paris: “Un spectacle de science-fiction sur l’œuvre de Wagner.” http://www.syfy.fr/dossier/autres-territoires

Alex, Second City is still around…somewhat unfortunately. Improve can become its own wearisome cliche in time….

Matthias – my apologies for taking the piss. I’ve been sitting at home in sweat pants for the past two days because my office was shut down for the storm. Pleading cabin fever doesn’t give me a total pass, but I will say that I found your comment of “That a lot of the other comics in Heavy Metal are borderline unreadable is just because they’re bad” to be really, really funny. Even collegial conversations need room to acknowledge humorous turns of phrase, surely?

Suat and Noah are making me feel like I farted in the elevator by mentioning Y: the Last Man. To be honest, my weak-ass “I dunno, I liked it” opinion is nowhere near as passionate as the prevailing “it’s Terrible” consensus, so arguing against that particular orthodoxy isn’t really worth my time and energy. Won’t happen again.

Suat – I agree that Heavy Metal could stand to be rehabilitated, but I’m not sure that the early issues are actually better than the current material – just different, which is the crux of my conundrum. To a certain extent, I get the sense that appointing Ted White as editor in 1980 was a step in that direction – bringing some kind of respectability to the magazine by bringing in columnists and changing the look and feel of the experience. Whether it actually worked is another question.

I do feel compelled to point out that AB’s rebuttal “‘Le Garage Hermétique de Jerry Cornelius’ was designed from the beginning as an improvisational riff from issue to issue” is pretty darn close to an authorial intent argument. We, the readers, are meant to know that Moebius designed this comic to do certain things. How was that communicated to the readers within the work? And how is a reader who doesn’t know that’s what Moebius intended meant to interpret the comic?

I understand that comics has other options beyond the narrative – I own the Abstract Comics anthology and have made art comics in the recent past. Still, it begs the question of whether the average reader is wrong to approach any given comics story expecting narrative. What other expectation should they bring to the artform? And how should that expectation be managed by the creator?

And that’s a large part of where Heavy Metal and the current art comics movement overlap – they both bring that same sensibility of “comics can do other things, you should totally know that going in” to the table. As a primarily narrative reader, my default assumption is always going to be that a comic is narrative in nature until proven otherwise. And, from that perspective, even my own art comics always feel like a failure to me because I’m not putting enough effort into trying to actually tell a story, however rudimentary.

I guess we could spend the next three days trying to convince each other that comics are/are not an inherently narrative artform, but that would mean depriving Noah of potential headline topics. I say they are and that’s the criteria that I used to judge these works. I guess there’s value in telling me that my criteria are wrong…? There’s certainly entertainment value in telling me that my tastes in science fiction comics are wrong.

Y: The Last Man made the best 115 comics list we did a while back, so I’d say that the broader consensus is that it’s worthwhile. I just had a really negative reaction to it….

I’ll pipe in and say that I liked Y: The Last Man (although not enough to give it any votes on the best-of list), but I read it while it was coming out, for the most part, so I don’t know how well it would hold up on a reread. I generally liked the writing; I think Brian K. Vaughan is smart and clever, and he was good with exciting cliffhangers. As a comment on gender or something, I’m not sure it had much to say, but it was a rollicking post-apocalyptic adventure around the world, with interesting looks at culture and such, and some good characterization. The art starts off pretty rudimentary, but I think Pia Guerra got better as the series went on. Basically, it’s solid entertainment, but I wouldn’t rank it among the best of sci-fi, Vertigo, or Vaughan. Well, maybe Vaughan, I dunno.

I think comics are narrative to the extent that they are as a medium the sequencing of images–and anytime you place things in a sequence you are constructing narrative even if that narrative is apple, orange, clown.

I do not think though that because of this that this means that the plot or characterization within comics has any kind of primacy over any other element within the medium.

With Moebius comics the importance is on the image, the world, and it’s wild fantastic ideas meant to tickle the imagination. It creates the fantastic.

It is obviously fairly unimportant what is happening with the plot. But that’s not a failing–that’s a creative choice that was made–and you either like it or you don’t.

Within the confines of what Moebius sets up in his stories–a failure would be a work that fails to create the fantastic otherworldly spectacle. The comic sort of lives or dies on the motion of his pencil. And that’s okay. It’s a type of comics. I enjoy those type of comics more, because I dig the atmospherics–and I dig comics as mood altering tech moreso than I’m interested in them for telling me a “good yarn”.

Suat, when was the last time you read “American Flagg?” I read the whole Chaykin run in the mid-90s. To my mind back then, anyway, he did his whole world-building in the first few issues and didn’t really add much beyond that. The issues blur together after a while. Certainly better than other mainstream titles, but still too commercial.

RM Rhodes – Please, if you like Y: the Last Man, go to the mat for it. One of the great problems in these sorts of discussions is that those who are the most loud and negative win. “I like it” is a perfectly legitimate reason to, well… like something.

Domingos, I don’t weigh in on deathly dull, airless comics so maybe you should keep your trap shut about things you have no interest in yourself?

MG, please try to make your points without being unnecessarily insulting. That’s a warning; next time I’ll just delete your comment.

Sarah – I see where you’re coming from. I agree that “anytime you place things in a sequence you are constructing narrative” and would argue that you just made a foundational argument in favor of comics being an inherently narrative artform. You may or may not agree, but there you go.

I don’t know that narrative has primacy, exactly, but it is valid to judge an inherently narrative artform using the basic narrative critical toolset. The question really comes down to whether comics should ONLY be judged by those criteria.

Truthfully, I don’t know. My background is in storytelling, not art, so I bring certain biases to the table when I evaluate comics. I can see the other point of view, though – if you are an artist, it might make sense to be more interested in the linework, the color or the thousand other details that make up the composition on the page and consider the narrative aspects of the comic as a less important.

Given that comics is a hybrid artform, I don’t necessarily think that either approach is entirely correct, but I do stand by my biases as they apply to my evaluation criteria. I’m allowed to do that, right?

Our disagreement isn’t that comics are foundationally narrative. The disagreement is over the improper imposition of a particularly kind of narrative upon structures where they critically have little place.

Is Tarkovsky’s Mirror a densely plotted masterwork which seeks to spellbind you in the same manner as a Hitchcock classic? No. Of course not. And it would be weird to approach the Tarkovsky piece from that angle because you are not making a criticism that deals with the fundemental qualities of the work, really whatsoever. If the qualities which define a work are one thing, what sense does it make to judge the work on a completely different set of qualities that it never had any intention of being?

Narrative is just some kind of sequencing of events generating a context. It is not strictly speaking Plot, dialogue, or characterization. You can craft a narrative with no dialogue, no character development, and no plot–and it can be a masterpiece.

I mean you are free to do what you want. This is simply my critique of an approach which I find flawed. I’m barely keeping the names straight here long enough to make any of it personal.

And you’re back to the intent argument. I don’t see the point of special rules for experimental works – it’s too easy for people to hide behind the exceptions instead of trying to overcome creative challenges. I could prattle on about the need for a common critical framework, but I get the impression that we would be talking past each other.

I’m not arguing intent. I’m simply saying you don’t use a hammer to saw a board. Part of effective criticism is knowing what you are looking at. I have no idea what moebius personally thinks about his work but I do know within five minutes of reading it the rules under which the work establishes itself.

You can’t boilerplate mechanical criticisms across the board. I mean do you know a surrealist or mannerist painting for not being realism? Different works have different rules and its got nothing to do with authorial intent.

Steven Samuels- I was saying that Corben’s whole career could not be dismissed as adolescent. In my comment you linked to, I did say the Den story is not very good, but the depictions of the body in all its variety, transformations and vulnerability was the strength of the work.

The immature humor in a lot of Corben’s work completely damages what I think is one of his best strengths in works like Den: the frankness of the nudity. From reading things that Corben has said and the overall approach of his work, it seems there is a strive towards a sort of expanded view of humans, animals, genders and all types of things transcending usual definitions; immature earthling jokes totally spoil this.

I think these cheeky jokes done huge damage to House Of Usher in particular. Bodyssey was completely made of lame jokes.

Corben is in my top 5 comic artists but I wouldnt rate most of the stories very high.

Tim Conrad did some gorgeous work in Epic Illustrated that have turned into collected editions Toadswart D’ Amplestone and Almuric. He had an accident that led to serious memory problems but he has recently made a comeback with a Hunchback book from Darkhorse.

I like a good story, but stories need to be pushed away more often and they often spoil narratives that dont need them. I think most of the sf/fantasy/horror comics would be far better if they were more focused on image sequences than stories and that is exactly the direction they have turned in recent underground/alternative comics. Horror and fantasy movies need to get rid of story more often. When I was a kid I always was baffled by the idea that horror movies had stories full of focus and concern for stupid boring normal people and their stupid boring friends and families, the idea the the “good guys” usually win baffled me even more.

“Cognitive Dissonance” is how science fiction has been defined by some experts.

RM…do you have any appreciation of poetry? Lots of poetry isn’t particularly narrative, and a good bit of modernist poetry is deliberately fragmented. Is that a weakness of the poetry?

I think it’s a mistake to make this about experimental or non-experimental work too. There’s a lot of nonsense verse (like some of Dr. Seuss, for example, or Edward Lear) that doesn’t have much of a narrative. The issue isn’t that it’s experimental, but that it’s just not all that concerned with telling a story, because it’s doing other things (thinking about sound and rhyme, or just stringing silly images together.)

This does have something to do with intent…but it’s not individual intent alone. It’s what works or genres you’re in conversation with in part.

Steven: “Suat, when was the last time you read “American Flagg?”

Yep, it could be one of those deceitful memory things since I last read American Flagg! as the issues came out. Maybe Hard Times and Southern Comfort a couple of times a few years later. That was the best of American Flagg! I think. But I can’t imagine it’s worse than Y: The Last Man (which is still better than TV trash like Revolution I should add).

If I said Brandon Graham’s work on Prophet was the best written American Sci-fi comic of saaaay the last 30 years(or farther?) what works would you reference to laugh in my face?

Because I’m having trouble thinking of many works that surpass it in terms of sheer beautiful writing.

——————-

MG says:

“I like it” is a perfectly legitimate reason to, well… like something.

——————–

Indeed; however, it fails to communicate to others who don’t, what it is in the work that you enjoy. And it’s also useful in clarifying to yourself, “Why do I like this? What factors in the work appeal to me?”

For that matter, it’s also legitimate to say “I don’t like this”; the problem is that people then assume and argue, “therefore it’s crap.”

——————-

sarah horrocks says:

Our disagreement isn’t that comics are foundationally narrative. The disagreement is over the improper imposition of a particularly kind of narrative upon structures where they critically have little place.

Is Tarkovsky’s Mirror a densely plotted masterwork which seeks to spellbind you in the same manner as a Hitchcock classic? No. Of course not. And it would be weird to approach the Tarkovsky piece from that angle because you are not making a criticism that deals with the fundemental qualities of the work, really whatsoever. If the qualities which define a work are one thing, what sense does it make to judge the work on a completely different set of qualities that it never had any intention of being?

———————

Bravo! What an utterly sensible observation, so routinely ignored, We get, in effect, arguments like “Jack Kirby’s comics are crap because they fail to live up to the literary standards of a Henry James novel.”

As for comics being “inherently narrative,” Scott McCloud likely made the argument first — certainly most prominently — in noting how our mind tends to impose some sort of unifying narrative and connection.

(The sinister part of all this is shown when a GOP newspaper ad against a Democratic officeholder [ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Cleland ] — a decorated war hero — put his photo next to a photo of Saddam Hussein. The brilliant mind of Georgia voters read this as “He’s a friend of terrorists! His photo is right next to a photo of Saddam Hussein!” Needless to say, the strategy worked…)

However, though, that doesn’t mean a work can’t either ignore or actively work against those tendencies and expectations…

———————–

Robert Adam Gilmour says:

… I was saying that Corben’s whole career could not be dismissed as adolescent.

————————

Yes; there was much satire, even one vividly anti-imperialist story, told from the point of view of aliens colonized by earthlings, in his earlier work.

Unfortunately the shallow, “serious” S&S stuff is what most have seen…

One of my dirty little secrets is that I’m not actually all that keen on poetry. I like some of it, but mostly where it cleaves closer to actual narrative (quel surprise!). I do like The Wasteland, but that’s more because I’m a fan of mashup culture in general and it’s a precursor in a lot of ways. Having said that, I am interested in picking up the Comics Poetry book because I like to take in a broad range of material, even if I do end up evaluating it on my fairly narrow criteria of “good.”

I have some weird issues with genre as well – which I haven’t entirely sorted out in my head or articulated to my satisfaction (I’ll get back to you when I do) – but the short version is that claiming something is “good for science fiction” or “good for experimental work” is damning it with faint praise. If you have to qualify the rules for evaluation, then you’re really not doing the work or the creator any favors. You’re basically saying “it won’t measure up against Tolstoy, but it’s good for what it is.” That’s fine, I guess, but it also puts the work into a box of your own construction to protect it from the larger world of criticism, like some hothouse flower.

My theory on this boils down to the platonic ideal of a reader in some distant future. They find the work in question on its own with no understanding or interest in the context or genre that the work was intended to fit into. Does the work stand on its own regardless of what critical toolbox any given reader brings to the table? As far as I’m concerned, that’s the crux of the issue.

If that reader comes away with an improper understanding of what he was meant to be getting out of the work because he didn’t have the “author’s notes” that someone or other deemed necessary to really appreciate it, the work probably failed in some way or another. Telling the reader that he was “reading it wrong” because the real instructions on how to read it were not actually in the body of the work is a dodge. Again, it does no favors to the creator to protest that the reader is “not getting it” because he used the wrong critical toolbox. If the work is successful in its own right, the right toolbox should be obvious.

You may not think that you are apologizing for Moebius by claiming that you need a certain toolbox to “get” what he was trying to do, but you are. It is very obvious what Moebius was trying to do – but the story was still a mess, regardless of whether he totally meant for it to be a mess. If that is important to you as a reader, then it’s a failing. If it’s not (which is a perfectly legitimate point of view – we all have our own biases), then it’s not a failing. Telling me I’m wrong because I obviously used the wrong toolbox, and thus the perceived failures were not actually failures if I had only looked at it from a different perspective, doesn’t actually make a good argument. It makes a good apology, though.

RM, like I said, I haven’t really read Moebius, so this isn’t about him in particular for me…but I think you’re Platonic ideal of art that needs no context is unworkable. Any art needs context. At the very least, you need to be able to speak the language (for written work) — which can be a huge deal, especially over time as dialects change.

This may seem like a tangential issue, but I don’t think it is. Art is a form of communication; as such, it requires a the basis for communication — a shared community, in which the artistic “speech” makes sense and can be interpreted. That’s the case with *any* art. It’s very much the case with Shakespeare, for example (there have been some fairly famous anthropological essays written about non-Western indigenous cultures reading Hamlet, and about how, rather than getting its “universal” human appeal, they simply don’t understand it or like it, since the preconceptions are all wrong.)

So trying to fit all art to a single set of criteria doesn’t mean you’ve found a universal value; it just means you’re using one particular provincial value system. If you acknowledge that (i.e., this is what I happen to like) there’s no problem. If you start to shift to claiming that your partial view is in fact universal though (as you seem to be doing at various points), it seems like you run into trouble.

That doesn’t mean you can’t compare works on various grounds or for various reasons — standards and communities overlap in lots of ways, and there’s no reason not to rate one value (say, good clear storytelling) above others, as long as you’re clear what you’re doing. But hoping for a view from nowhere (or from the far future) as some sort of absolute is just not very convincing to me.

I’m miscommunicating if I’m putting across that I don’t think sci-fi genre work is as good as anything else.

I’m still reading Dune on the first go through, but there are lines in this book so magical that they are already amongst my favorite. Game of Thrones is an exceptional work. Prophet blows my mind every month. I obviously feel pretty passionate about Druillet’s work. I love Giger and Beksinski’s sci-fi/horror paintings.

And I say all of this as someone whose background in education IS the study of literature.

I think what upsets people about sci-fi is that they feel it’s “merely” escapism, and they’ve been taught to view anything remotely escapist as a pejorative. But it is these fantastic other worlds that most bend and expand your mind, and allow you for change expectations and ideas when you end the work and come back to reality. Sci-fi as a genre is a world shaper. We probably wouldn’t be having this conversation on this thing the internet without science-fiction and it’s mind altering qualities. Sci-fi is good drugs.

And Druillet and Moebius are for me masters of it. I find their works hugely inspirational, and full of ideas that are even today fresh and interesting. Even just technically what they were able to pull off was virtuoso work. There are certain mechanics within western comic art that they absolutely are the gold standard for.

Corben is I feel something of a different beast entirely. I see Corben more in the horror mold–though that’s shaped because most of the Corben I’ve read, and continue to read is horror. And I think horror operates with a completely different set of rules from any other genre but porn. I think great horror is not plot based at all, but rather about generating a particular mind state within the reader–like the example I always use is in the film Texas Chainsaw massacre–the original–there’s this section where he’s chasing the girl through the woods with his chainsaw, and the night is blue, and there’s almost an impossible amount of branches that keep getting in the girl’s way–and leatherface is always like just inches behind her no matter how fast she runs–and the forest actually morphs within this scene and elongates from how we had previously seen it in the film. Suddenly it changes into this seemingly neverending labryinth. She stars running across the screen in directions and at distances that should get her out of the forest–but don’t. In terms of realism it is a failure. But what the work is engaging with is that creepy dream logic that infuses all of the best nightmares.

Most horror work in film and comics of the last 20 years have been failures because they do not understand that this element is what makes horror work. The plot and the realism is what detracts you from the sublime horror moment where art melds with dream. Similar to the moment porn melds with fantasy.

Horror, particularly in comics I think, should be less interested in plot and story compared to any other genre of comics–and be interested in creating these nightmare images and scenarios that come off of the page. More horror comics creators need to be surrealist pornographers.

This got off track. But horror is I feel an instance where adherence to plot and characterization rules that work in other genres produces spectacular failures of horror. The only thing you are left with in a horror work whose focus are those elements is a gore-fest, and trying to out-shock the last person. But true horror is not just gore, or shock–it’s much more subversive than that. And so horror is a huge indictment as a genre of this particular approach.

For me an excellent work of true horror did come out in comics this year, and it was done by Richard Corben. It was called Ragemoor. I remember reading the opening pages of that book and that section where the castle history is being explained–gave me chills like a comic hadn’t in a long long time. I think Corben has always had the chops to do great horror, and sometimes he has–but when he has failed it has been because of writing which is overly concerned with itself. Which is why it is hard to explain to people Corben’s place in comics history–because he truly is one of the greats–but he has very few works that are masterworks–and if you don’t get Corben art, and can’t focus in on what he’s doing visually on the page–you won’t understand.

Druillet and Moebius are different in that I think both of them the writing is in concert with the art–probably because they are handling both functions.

If Noah ever implements technology to “like” comments, I’ll come back and do so for this last one by Sarah Horrocks. Damn good call on the effectiveness of horror, Corben’s awesomeness, and Ragemoor.

No like button…but I have highlighted Sarah’s comment here.

Thank you, Noah. I was just reading through this thread, feverishly I might add, in hopes of finding out if somebody had finally put it across to RM that his criteria for evaluation was provincial at best (narrow-minded, wrong-headed, self-serving and contemptuous being merely a few other terms I’d considered, had my response been necessary).

It seems to me that in speaking of comics such as Heavy Metal during it first fabled years, it’s important to set yourself in place historically – if not to enjoy them, then at least to understand the amount of praise they’ve garnered throughout the years. I mean, it’s standard procedure in any responsible appreciation of art (well, at least in that strain of academic analysis that still concedes a certain ground to structuralist thought and practice). I’m of the opinion that they are, in fact, somewhat overrated, but I’ve come to expect that of almost the entirety of the comics canon.

Is it fair to say that if one’s coming from the study of literature, there’s a definite learning curve when it comes to other forms of narrative storytelling? I remember it being so when I first encountered Bergman and Fellini, but I kept at it, wondering what it was that everyone seemed to find compelling about them, being that I had never so much as seen a film from a place other than the US (and the occasional Mexican or British film that fit squarely within the strict Aristotelian model of dramatic storytelling I’d been fed through my childhood and adolescence). What I mean is, shouldn’t the same be expected of people coming into comics? Although, to be fair, I’m sure a more apt comparison would be my recent awakening to the wonders of early Hammer Horror and giallo filmmakers of the 60’s and 70’s. I think that’s more relevant to the majority of the comics of a bygone era that are frequently dug up and discussed in forums such as this.

Noah – I absolutely agree that the question of context is central to the understanding and appreciation of art. But the important thing to remember about context is that it has the potential to change. A painting hung in the East Wing of the National Gallery of Art has a different context than the same painting found in a dusty garage. But does the change of context change the inherent artistic value of the painting? Another example of art that we consume without regard to original context: music. Hearing The Beatles or Janice Joplin in the supermarket is now commonplace. Does the different venue change the quality of the music?

And yes, I agree that one of the central struggles of criticism is the balance between personal opinion (admitting to your biases and how they shape the subjective evaluation) and the objective (using a common taxonomy and terminology so that you’re talking apples to apples, not apples to pineapples).

Where I’m struggling in this conversation is that I admitted up front (or thought I did, I could be wrong) that I evaluated these works based on my own personal criteria, but then was told that my criteria was incorrect because it didn’t take into account the intentions of the artist – Sarah actually indicated that I brought the wrong toolbox.

But if it’s my criteria, isn’t it my right to disregard the intention and try to just look at the work from the viewpoint of the reader who has no context? Sure, it’s probably an unattainable reach – if only because of the biases I bring to the table – but part of being a human being is doing things that will probably fail on the off chance that you might actual get something useful out of the attempt.

(I’m actually very sad that I’m not sitting in a pub having this conversation in person. It’s been very enjoyable.)

Sarah – It was not my intention (hah!) to imply that you or anyone else here thought that sci-fi or work in any other genre was better or worse anything else. Like I said, I have a complicated relationship with the concept of genre and we’re not really on good speaking terms at the moment. Nice essay, though.

Cristian – Thanks! It’s been a while since anyone called me “narrow-minded, wrong-headed, self-serving and contemptuous.” Glad to know that my much-vaunted smugness still comes through after all these years. It’s the little things.

And one of the values of Art (if I can use the term as a collective noun) is that, by lasting beyond the death of its creators and their historical moments, it can preserve (if imperfectly) a continuity of context for future readers/seers.

Hey RM. Those are all good questions. I think context actually does often change the value of and/or our experience of art in various ways. That’s true for pop music, which is very much tied to its moment in various ways. (A quick example; Robert Johnson’s stature as authentic bluesman is arguably about *mis*understanding the context of his work. If you know that he was a Bing Crosby fan, for example, that punches a sizable hole through the narrative about him and his music, and arguably forces a reevaluation of the music itself.)

I think part of the disconnect here is that in your piece you don’t explain clearly what you are looking for in a story, or what “good” writing means to you? That ends up giving your claims a more universal weight than perhaps you intended. You come across as saying that Moebius is incompetent, rather than saying (for example) that he’s trying to do a William Borroughs/experimental thing which is (you believe) a bad idea.

There’d still be an argument, probably, but it would look a little different if you were saying that you didn’t think what Moebius was doing had value, rather than saying that Moebius is a bad writer. If that makes sense.

RM – I speak only of what I know.

In relation to what you wrote on context, I think you’re equating context with venue. Those are two very different things, the latter of which Noah (if I remember correctly) didn’t touch upon. Context is more than the place where the work of art was first published or put on display. It takes into account the social and artistic concerns of the time and allows one to delve into the historical moment that saw fit to produce, in this case, its own interpretation of a genre comic, such as The Airtight Garage.

Of course nobody’s in any obligation to heed the words of the many who proclaim Moebius to be a godsend of some sort, but it’s only fair that if you’re inclined to think critically of why he’s held in such high regard you also take into account that it’s not a work of art fit to some universal mold. It’s a (sort of) turning point in sci-fi comics for a reason. The paradigm shifted and did so specifically because it worked against the norm. That’s part of the context, even if at the end of the day you’re of the opinion that it fails in some way.

The two things that came up when I was discussing this thread with my wife over dinner last night was the fact that 1) I didn’t emphasize how personal this interpretation was in the original post and 2) I brought Moebius into the discussion in such a way that it seemed like I was pissing on him from a great height. Any discussion of Moebius attracts attention the way a dead squirrel attracts flies. And it’s not so much that I believe that Moebius is bad, per se (quite the contrary), more that The Airtight Garage has a sprawling narrative that doesn’t actually work. But that’s dead horse has been beaten more than is probably necessary.

Christian – I actually read that as you trying to get a rise out of me, which is a silly tactic (as I demonstrated earlier), but it usually requires that you have a better read on your target’s self-esteem. Sorry that didn’t work out for you.

Having gotten the foreplay out of the way, the crux of my issue is a problem with the assertion that the context is critical to the understanding of the work because the context is not always going to be available to every reader. If the original context was important to every consumer of art ever, then we’d be issued liner notes when we filed into dance clubs instead of just, y’know, dancing to the music without caring what the creator was trying to do.

RM – Not a rise, just an assessment of your argumentative position. You see, I understand your insisting on this impossible future reader who, for some odd reason, lacks any context for the work he or she has encountered. I also understand them not liking said work and, thus, throwing it aside. Heck, it’s a natural sort of way to interact with ANY product of, in most cases, strictly cultural importance. We all do so to one degree or another. Now, the mistake lies in pretending that that person is in any authoritative position to comment on said work of art. Sure, his or her insights are still valid and worth discussing, but whenever they veer into categorically condemning or dealing away, then, I think it’s fair to call into question what criteria is necessary before proceeding with said dismissal.

Granted, as you have pointed out more than once, you didn’t do so explicitly in regards to most of the artists discussed. That’s fair and appreciated. You’ve been careful in doing so and I commend you, but I still take umbrage at your insistence, way back, on a supposed “artist’s intent” and this recent “context = venue” thing.

Still, it’s been a pleasure to read this back and forth. Fun stuff, considering I wasn’t expecting a morning quite like this.

RM, dance clubs are extremely self-selecting though. People go there and pay a fair amount of money because they already have a very good idea of the context, and of what to expect. Probably the folks there have listened to a good bit of dance music already…and/or, if it’s a first time thing, they’re generally there with friends who can explain things to them (and often do — pop music is very much reliant on social networks for transmission of information.)

On the other hand, when Shakespeare gets taught, it’s generally done with a *lot* of context, including things like footnotes, background on what kind of theater the plays were performed in, what Shakespeare’s worldview was, what his sources were, etc. etc. Most people looking at Shakespeare for the first time need that; they’re not equipped to figure it out instantly (and how could they be?)

I don’t really know why it diminishes a work of art to acknowledge that not everyone in the world can appreciate it without some context. Again, the biggest barrier for written work is going to be language…and for that matter, indigenous peoples often can’t parse photographs at all, if they haven’t seen them.