It’s very likely that Chris Ware’s Building Stories will be the most publicized alternative comic release of 2012. Like Habibi last year, it will be one of the few comics that the larger public will hear about, and will be encouraged to read. NPR’s Glen Weldon thoughtfully reviews it, concluding that it “is beautiful.” The Telegraph announces, “his new book, if one can call it that without being reductionist, is a work of such startling genius that it is difficult to know where to begin,” and that “Ware’s latest offering has elevated the graphic novel form to new heights.” EW’s Melissa Maerz gives the book an A+. Sam Leith, an author, journalist and occasional critic for the Guardian, relates, “There’s nobody else doing anything in this medium that remotely approaches Ware for originality, plangency, complexity and exactitude. Astonishment is an entirely appropriate response.” The New Yorker, in which Ware regularly contributes and in which an excerpt of Building Stories has been published, declared its release a “momentous event in the world of comics,” contextualizing the event in a way that’s hard to put a finger on. So is a ‘momentous event in the world of comics’ news or not? Required reading?

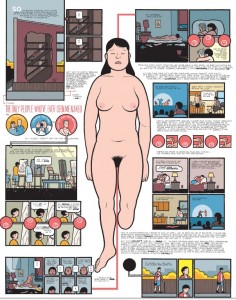

Building Stories will probably top bestseller charts for comics until Christmas, but it’ll still be a hard sell, even with reduced prejudice toward comics. Reading comics takes a lot of effort for those unaccustomed to it, and is a little ironic, considering comics’ association with instructional and children’s literature. And when a typical page looks like this:

On the other hand, the intense stylization and design of Ware’s work could make it easier to grasp what is “impressive” or “extraordinary” about it– no critical vocabulary or understanding of the comics medium is needed to “get it.” Still, picking up a Graphic Novel is an intellectual adventure for most people, and while they can be quicker reads, for an infrequent comics reader, Building Stories seems to require an intimidating amount of time and energy to absorb and reflect on.

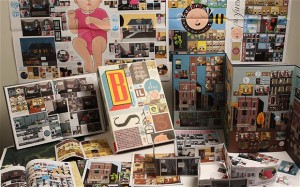

On top of that, Building Stories isn’t really a book as much as a box containing 14 intertwining narratives of varying length and form.

Photo courtesy of Julien Andrews and The Telegraph

It resists straightforward reading or easy transport. This could make the work even more daunting if it were to be consumed as a commute or a relaxing read. Except that it won’t be– Ware’s Building Stories rewards the casual reader’s belief that reading good comics is an experience worth having every now and then, but not a habit that can be integrated into one’s regular routine. Rather than challenge his audience’s preconceptions of the value of comics as something to build into one’s day-to-day, Building Stories reinforces the idea that worthwhile comics are blue moon events, and reading them is a temporary interruption in normal behavior.

In Building Stories’s defense, Ware champions the survival of print, and active reading habits. Building Stories is untranslatable to an ereader, and asserts the value of a book as an art object to be physically experienced and actively engaged. Building Stories also blurs the boundary between ‘comic books’ and the field of ‘artist’s books’ and ‘book arts’– this could be a post in itself, but still worth noting here. However, its worth wondering whether comics are already seen more as objects than vehicles for content, and whether their objecthood (and collectability) is supported by the American marketplace and culture.

Additionally, the publicity of Building Stories helps comics as a field more than it hinders it. If more exceptional works are publicized, its harder to assume that they are only exceptions in an undistinguished industry. Still, for most, reading a comic is an eccentricity, a curiosity, a ‘novelty,’ and the format of Building Stories plays into the sense of gimmickry that infrequent readers bring to reading comics. If the merit of reading comics lies in the strangeness of doing it, why not make the experience increasingly elaborate and fanciful? As the form eclipses the content, mediocre storytelling runs the risk of being excused due to unfamiliarity or low expectations of comics in the first place. Fittingly, novelty is central to Ware’s work: ragtime aesthetics, and turn of the century advertising and consumerism abound throughout Building Stories and his career. Perhaps some of his success lies in his work’s resonance with occasional reader’s nostalgic, fanciful approaches to comics, evidenced in most press coverage of releases. It’s worth noting that lifting the cover of Building Stories isn’t unlike opening a game box, or a trunk of childhood artifacts.

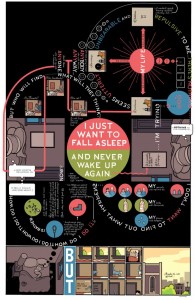

Beyond that, Ware presents a cabinet of curiosities, a wunderkammer. Its fragmented form compliments the fact that it follows several character’s perspectives, but is it overkill? Derik Badman wrote a few illuminating meditations here, including, “The narrative itself is already quite non-linear, most of the ‘chapters’ include movements through the time of memory/recall, and I think something of the protagonist’s story (and the emotional impact of it) is lost if you end up reading the later parts before the earlier parts (chronologically speaking).” On the other hand, the contributor’s to The Comic’s Journal ongoing, laudatory roundtable find the effect “sublime,” ” a kaleidoscopic vision of simultaneous human frailty and possibility”, “aspires to a graphic novel on the scale of James Joyce’s Ulysses,” and maybe most observantly, “showcases the comic medium itself by including representative examples of all its sundry forms: comic books, mini-comics, newspaper comics, chapbooks and picture books.” Building Stories evades critical readings on its overall pacing and structure: these decisions are left up to the reader, who likely chooses what to read by chance. Without skimming the pages in advance for certain visual clues, (including Ware’s recent adoption of a Clowesian and somewhat creepy drawing style,) it’s hard to predict what each booklet will hold, and many events are revisited and re-evaluated as the main character ages. There are moments of poetry, and some great easter-egg moments as one stitches sequences from different volumes together (if that’s a motivator.) Finally, a linear reading may not be the best– the later chapters of Building Stories are wearingly over-narrated, and would be a tedious way to finish the story. Building Stories as a whole is a very uneven work, and the question remains as to whether the box of stories approach enhances the material, hinders it, or if it simply cloaks the fact that, after a decade of waiting, this may not be Ware’s best work.

It’s probably unfair to say that Ware is invested in non-habituated comics reading any more so than Pantheon, crafting fetishistic, beautifully awkward and expensive book formats. But, isn’t every comics publisher following suit? Building Stories is a collector’s item by nature, and its multiple readings will probably benefit multiple re-readings– a perfect and decorative addition to a home library collection, alongside Habibi and deluxe reprints of Prince Valiant and Pogo.

On the flip-side, the format of 2012’s other heralded release, Allison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother?, is hardly experimental, but perhaps more revolutionary considering comics industry’s focus on ‘the object.’ Interestingly, Are You My Mother? embraces a lot of qualities that made comics popular in the first place. As a pretty standard book, Are You My Mother? is expected to speak for itself, and it can easily be read at one’s convenience, and in public, (which matters more to some than others.) Historically, as collection eclipsed disposability in the American market, comics’ status as an ‘object’ was magnified.

It’s possible that, despite comics’ greater acceptance as ‘literature’ than as ‘art,’ the industry is at a crossroads as to whether to pursue an ‘art object’ or ‘literature’ route. Building Stories exemplifies the former path, while Are You My Mother? follows the latter. Each route bears repurcussions for comics consumption, several of them class-based. In the United States, students are expected to graduate with some familiarity with a handful of great works, and their history, and to learn basic critical frameworks to apply to other books. Art, when not nixed from the curriculum altogether, is taught more often as a practice rather than as a history and theory. Those who learn about art are often those who can afford to, or do so at the expense of lifetimes of loans. Literature is transportable, and can fit itself into a variety of lifestyles (long bus and subway rides, for instance.) Art, focused as it is on physical, singular presences, (not duplicates,) must be approached in certain institutions, during certain hours. As a consumer, only the wealthy and initiated can participate in the collection of ‘the masters,’ while a paperback of Dostoevsky will not be less authentic than the leatherbound edition. The leather-bound is preferred when the discussion veers from literature to a subset of art collection– rare book collection. The repurcussions of Building Stories extends farther than just gimmickry, but also those of privilege. Purchased at a bookstore, Building Stories is a fifty dollar book. Will libraries, which have done so much to make comics available to the public, easily be able to loan it? And why resist digital reading? With the advent of e-readers, color comics can be as cheap to publish and as easy to find as a text book– one less hurdle in their production and accessibility. It’s worth crossing one’s fingers that, in its resentment of art-world prestige, comics will avoid enviously replicating the worst aspects of fine art. Bart Beatty’s Comics Versus Art delves much more fully into this idea– and is very much worth the read.

Perhaps making an experimental box of comics is truly an elevation of the form. Perhaps other visions of comics readership, where a handful of comics, both brilliant and bad, are sprinkled around the e-reader screens of a commuter car, is wishful, or unnecessary, (or found only in Japan.) (Apologies for the USA centrism of this piece– unfortunately, it will continue to the very end.) Comics may have a nice niche here in the States– the rare, quirky read for some of most people, and objects of obsession for few. But is there something urgent, something missing, that comics can bring to wider culture? Something that books and film and music or any other medium can’t or won’t contribute, that comics uniquely can? Something that is needed, and should be as accessible as possible? Would it matter if comics became more prevalent than they are– that comics became more accessible than inaccessible? Those outside the industry may not care one way or another– they are probably waiting for comics to answer for that.

I’m surprised that there aren’t more comments here yet. Maybe the argument isn’t phrased sufficiently pugnaciously?

Be that as it may, I think you raise a number of really interesting points. The contrast between a comics future as determined by Ware and one determined by Bechdel seems especially worth thinking about (though of course the two aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive.) I think your hints about the explicitly nostalgic nature of Ware’s project — the rejection of digital, the kid’s game box — also seems on the money — and perhaps ties in (in not entirely laudatory ways) with his emphasis on the theme of memory as content. It maybe connects with the tweeness that Bert Stabler sees in Ware’s work — it can be stiflingly elegiac.

It’s really not a very elegiac book. The past definitely doesn’t come off any better than the present (maybe worse)—and the same is true in Jimmy Corrigan.

It’s also not really much of a kids’ game box…There’s no game, is there…and the book is definitely not for kids. (Although there are a couple of faux-kids constructions in it).

I would say the Bechdel book is more elegiac than the Ware one. It’s all about revisiting one’s past and coming to terms with it. I don’t see that in Building Stories at all…or not much.

Thank you for the comments, guys!

Noah, you may be right… I wonder what would happen if we changed the subtitle to “Uninspired gimmickry in Chris Ware’s Building Stories”

I agree with you that Bechdel’s approach and Ware’s approach (which are already misleadingly named… maybe we should say Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s approach and Pantheon’s approach?) aren’t mutually exclusive. Comics affords so much visual and physical freedom in creating the book object, I would never want that to be lost. But I’m worried that the emphasis placed on comic’s formal aspects, (and generally, Look! It’s A Comic!) will continue rewarding tricky books with poor storytelling. If a comic that is actually a box of fourteen comics is treated like a huge milestone in the genre… that’s where I get nervous. I really don’t think that Chris Ware’s book is a landmark occasion.

Eric– I think that the elegiac nature of Ware’s work (if there is one,) is sort of mourning a displaced nostalgia, a displaced childhood. His work is very aware of what is very painful about childhood, and what was really awful about previous eras, but amidst the depressing spells, the characters quiet up, and the eye of the book moves beyond them, and captures these incredible moments of poetry. These are the moments other critics call mundane– morning light coming through the window a certain way, an orange in the refrigerator– mundane in that they are instantly recognizable from daily life, but generally not resummoned back. I think that Ware is a master of recalling the certain details that we stopped noticing after childhood, or in the case of Building Stories, young adulthood. Personally, I feel that Building Stories is elegiac for the earlier chapters of itself, and maybe unintentionally– Ware’s earlier style matches up with the first chapters, where the protagonist is in her young twenties, and the book, on the whole, is much quieter and understated and depressing. The later chapters, where she is a young mother, are over-written and drawn with a lot more flash. Wonderfully, the protagonist recalls something like, “I think I lived more poetically back then.”

I think what makes Ware’s work strong is that he is not melodramatically elegiac– longing for some Old Kentucky Home that was ripped away from him at some point. Ware knows that there is no home like that, and so has nothing to do with the longing, except let it linger over the small details that somewhat recall something lost.

As for the game box approach, I think Ware was very self consciously recalling one. Building Stories has the same dimensions and construction as a game box: to compare:

Monopoly: 15.8 x 10.6 x 2.1 inches

The Game of Life: 16 x 10.5 x 2.7 inches

Building Stories: 16.6 x11.7 x 1.9 inches

The major difference being that Building Stories is about 3 pounds heavier. It’d be worth looking at whether these were the proportions of gameboxes in Ware’s childhood, but they certainly were in mine.

Additionally, one of the books insides is bound in the matter of a fold-out game board, with the book cloth back and the crisp white paper front… I like the effect, as if Ware is riffing on how his style, little shapes connected with arrow pathways, could be played like a round of Chutes and Ladders.

Finally, to return to elegies, I’m not sure Are You My Mother is more mournful than Building Stories… I think the lack of clear, (and perhaps masculine) emotion is partly why some feel ambivalent about the book in comparison to Fun Home.

I’m taking your marketing advice Kailyn and promoting the post with your suggested subhead. What the hey; worth a shot.

Last month I was sent an early promo copy of Building Stories, but I have had a problem formulating a response. Firstly, one of the editors at PW wanted to interview Ware himself, and did quite a good job of it, so that venue was out. At that time, HU was in the middle of the hatefest, which began with a major slag on Ware, so that wasn’t really happening either. And besides…though I’ve admired Ware’s comics since the earliest issues of Acme, as it turned out, I don’t actually like Building Stories as much as I do Ware’s other work. Lint for instance seems more complete, more satisfying of a reading experience. I’m not entirely convinced that this most recent book holds together as well as we are told it should. The “Lego” drawing style here begins to feel a little repetitive and some of the sections seem excessively hostile to reading, in that they are printed way too damned small to read the type. My eyesight is fine, but I literally had to use a fucking magnifying glass. Truthfully, I don’t appreciate the Bee comics much. And, while some of the sections involving the the amputee heroine are nicely done and even thoughtfully moving in the temporally layered way that Ware does so well, a lot of it in the end seems to express a conservative viewpoint that I don’t care for…for instance, a major theme that could be taken away from the work is that it is against abortion.

And the box seems to be a gimmick, perhaps one suggested by the publishers as a way to make some loose ends of Ware’s recent output into a “book”—-since so many graphic novel publishers seem to display a desperation for quick product, when dealing with the slow output of authors involved in such a difficult and time-consuming medium. I feel the reservations that Kailyn expresses above—-why is it packaged like a board game and why are a few strips printed on a folding heavy board? I can see why parts of it are made huge—-it works nicely when the reader unfolds the tabloid section to see the nearly life-sized daughter looking down at one, as she does while playing with her mother in the story, but why is a significant section printed way too small in a tiny book that looks like a “Golden Book” that has some badly applied golden tape on the spine? Why the little oblong strip books? On the upside, with a little shuffling I was able to fit most of my other oversized Ware books into the box as well, so it sort of saved me some storage space. But the rush of critics stumbling all over each other to praise this as the project that should define what comics are about in a time that most publishing is in a headlong rush to self-destruct into digital formats is a little disconcerting as well, when the main thing I take away from it, no matter how much I respect Ware’s abilities, is an nagging unease at the content and and the actual physical discomfort of reading it—-in particular, a severe case of eyestrain. Okay, I will read it again and maybe alter my opinions, but that is how I feel right now.

A point I forgot to make is that when one sees the folding heavy board in the box, it seems like a game board and one expects to find little pieces to move around on it—but they aren’t there. It seems to me that if the box had been Ware’s idea, he would have included something for the reader to construct in it, like a little building or something, a realizing of its 3 dimensionality that might help make sense of the silly business of the “voice of the building”. As it is, one expects there to be something like that, but there isn’t. In the early isssues of Acme he DID include odd paper objects to cut out and construct, it is how his mind works and for that reason, the whole boxed-up business with no purpose seems suspect.

James–

I love your comments. Thank you for posting! I resonate with a lot of the points you bring up, and wish I pursued some of these ideas a little more thoroughly in the piece.

I think there’s a lot of mileage in the hypothesis that the box idea (or at least execution) was Pantheon’s influence more than Ware’s, or an unsuccessful matching of their two philosophies. What struck me wasn’t just the cheapness or randomness of the binding, but the absence of binding in about half of the books. A lot of the books are just stapled, folded pages, like printers proofs with the bleeds chopped off. I think the box conceals the fact that the book never came together as a book, and is trying to play off a weakness as a strength.

Which comes back to your comment about “the rush of critics stumbling all over each other to praise this as the project that should define what comics are about.” I’m genuinely worried that gimmickry like Building Stories is not only what ‘redefines’ comics for people, but what defines it in the first place. That poor storytelling isn’t only excusable, but expected, because comics are more about their form anyway. And the more nostalgic/eccentric, the better, and more notable.

Thanks again– the remark on storing Ware’s books inside BS isn’t only hilarious, but a great idea.

I haven’t seen this box, so, my question is: is it worth it to buy it if you already own all the ACME library books? What I infer from what you are saying is that Ware lost interest in what was supposed to be his magnum opus and the publisher tried to conceal the fact in a fancy packaging.

Addressing what you are saying more directly Kailyn: time and time again an artist got caught in his/her own style. The market kind of encourages this because it sees artists as trademarks. It happens all the time in gallery art (Picasso fought it quite successfully I guess, but Picasso was Picasso). It’s a known process. If the public can see it in the visual arts’ world and cannot see it in comics it’s the public’s problem, not comics’ problem. That said I understand your concern because comics are still trying to redefine their social role.

I have bought the box, but haven’t read the comics yet. I can assure you, however, that there’s a lot there that hasn’t previously been published — about fifty pages worth — and remember, much of what’s previously been published wasn’t in ACME but in other places such as the New York Times Magazine, the New Yorker, Kramers, etc.

Also, there is no way that Pantheon made the decision to box the material for Ware, nor did they pressure him into stapling or folding the individual sheaves of comics in it — as with everything he does, it’s clearly his own decision, for better or worse. And keep in mind that this material would never have worked as a single book in any case, what with it’s wildly different formatting (there’s a big difference between the monumental format of Kramers 7 and some of the Branford the Bee strips, for example, never mind the ipad story).

I can’t really speak to the new material yet, but the development in Ware’s style over the past few years is not what Domingos’ describes — it’s really an evolution, rather than an issue of “getting caught.” I go back and forth on whether it’s a positive one or not, but he’s far from stagnating, stylistically.

(And I don’t think Picasso managed all that well after 1940 or so, what with him being Picasso and all).

I completely disagree re. Picasso, but that’s irrelevant now.

Matthias: I didn’t describe what’s happening with Ware’s style. As I said, I inferred from what’s written above.

Oh, and thanks for the info!…

Well, I should perhaps temper that Picasso remark — as you say, he managed fairly well tempering the expectations of the market, but I think he was less able to manage the limitations imposed by his own style in those latter decades. There are exceptions of course, but they are generally marked by comparatively dull and repetitive work. Of course, dull Picasso is still Picasso.

Picasso produced a lot. It’s only natural that some of it isn’t that great. But we can agree, I guess, that Picasso was aware that market expectations can be stifling changing styles as he changed women (literally).

Yeah, post-Dora Maar it kinda got dull…

Wow, again, comments designed to derail the actual subject of HU posts to something completely irrelevant. This kind of thing becomes tiresome. To get back to Ware, preserving the original formatting of the strips is not a factor as far as I can see, for instance the NY Times strips are a lot smaller here. It isn’t clear why all of the strips are printed and bound the way they are. There are even bits that are a single tiny folded piece of paper.

Well… his 1967 drawings are all, but dull…

Surely Picasso is always relevant. He’s Picasso!

Matthias (or anyone), has Ware discussed the packaging decision at all? I’d guess it was his decision too, but you seem more certain than just speculation….

Damn that Francis Bacon! I wrote “how is the greatest artist of the 20th century irrelevant?” and then the name “Bacon” popped into my head!

Noah: He discussed the packaging/format in this interview at Publisher’s Weekly: http://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/comics/article/54154-a-life-in-a-box-invention-clarity-and-meaning-in-chris-ware-s-building-stories.html

Derik, thanks for posting the link! It’s nice to hear Ware’s words himself– he’s already aware of a lot of this discussion, and it saves this thread from some speculative quicksand.

However, I think there’s something iffy about the fact that so many of the books are just published as stapled pages… judging by his use of splash pages and tableaus in his more recent work in Building Stories (they look just like New Yorker covers, and one was used as a fake alternative cover,) I’m surprised he didn’t include covers for them, and make them look like… well… comic book floppies. Which is pretty much the only print example left out of the library. Why did he leave so many of the books looking deliberately unfinished?

Domingos– I should have clarified better– I don’t believe that Ware’s style has stagnated at all. Instead it goes through several obvious evolutions through the pages of Building Stories. One of which is a greater use of naturalism, especially in his faces, and his use of close-ups.

Other critics have already pointed out that this book is gendered female, as opposed to Jimmy Corrigan’s masculine focus. I think this gendering occurs on many levels, past the sex of the protagonist. Ware reinforces this in his belief that the scattered library structure is more feminine. I’d also say that the focus of his evolved style (greater attention paid to facial expressions and corporality) is also gendered female… according to many film theorists, these are melodramatic focuses and tropes. Also melodramatic tropes: the traumatic loss of a child, the salvation and virtue of motherhood, domestic home spaces.

I think a lot of what’s interesting and awkward about Building Stories is Ware’s incorporation of melodrama into a previous masculine, highly modernist style.

Matthias– Thanks for the post! I absolutely agree with you about Ware’s style evolving, rather than stagnating. I hoped to imply that in my piece, but as my review of his new style was pejorative, (and maybe too pejorative, as its a fascinating change,) I could see where my judgment could have been confusing.

I think the link Derik posted supports that the library idea was Ware’s. I still agree with some of his reservations, and have a few of my own though… while I’m not the biggest fan of what Ware himself recognizes as ‘gimmickry,’ why was it so half-assed? Maybe that’s something worth blaming on Pantheon.

Of course I read that interview. It feels like he worked out his talking points, but it is not such a convincing explanation for the box…Joseph Cornell?…nor for the odd shapes and sizes of the components, and in relation to their original printings. And Kailyn’s point about covers is pertinent. The package doesn’t work for me. I know Ware is capable of varying his style more than he chooses to do. And really, is there a convincing rationale that can be made for the ridiculously tiny lettering? I was actually dreading trying to read the thing and it WAS taxing in places, as usual. BTW I’m not enjoying beating on Chris, he is a great talent.

Kailyn: your post was more about the packaging than anything else, right? Maybe it’s this aspect of Ware’s style that’s getting old, not other aspects in a multidimensional oeuvre. I find you too eager to blame Pantheon though. I must confess that I still didn’t hear what he has to say while writing this, but it’s understandable that the format “gimmick” would age badly because it is datable in the history of comics as a reaction to the dictatorship of floppies. Whe’ve past that now, right? On the other hand I’m not saying that everything was already done on the design side of things. The only thing that we, as readers, need to say to artists is: surprise us!…

I really agree with James. If Ware was afforded the possibility to make the comics any size he wanted, why didn’t he print them closer to original size? On the other hand, maybe the strain is part of the physicality of the reading experience? At that point, the project is getting a little too narcissistic.

Ditto with not wanting to beat on Ware unnecessarily. I think this is more of a circumstance of Ware, like many other cartoonists and comic books out there, has been failed by his publisher and editor. Or lack thereof.

From reading a few interviews and just knowing a bit about how he works, I think just about every decision relating to that book, including the packaging, is Ware’s sole responsibility. And everything you see there, whether tiny lettering or stapling, has been done with full awareness. He’s just like that. Whether that’s problematic or not is, of course, another matter — I’m looking forward to digging into the box as soon as I get the time…

As for floppies being out, yes they kind of are, but what Ware is reacting to here is digital media — a friend of mine compared this box to the kind of really elaborate silent movies that got made around the time sound was introduced, a kind of conservative, but also glorious celebration of a waning form.

I would have rather have seen it all in one giant book…and I don’t really believe that such a thing could not have been accomplished. Horizontals could be printed sidewise. White space is always an option…etc.

But that’s really just a convenience thing… It’s really not that hard to pile all of the stuff up on one’s nightstand, and read ’em one at a time. (And take a few with you if commuting or whatever). It’s kind of annoying, but reading it was really not that different an experience for me than reading a big GN in a single book.

The biggest distinction is that “you don’t really know what order to read stuff in”–but I don’t think it’s that big a deal. Lots of books are told “out of order”–and this book ends up being one of them unless you self-consciously figure out the chronology before actually reading (which I don’t see as a worthwhile thing to do). As it is, the chronology is not difficult to reconstruct retrospectively.

In the end, I liked it. I found the packaging somewhat annoying, but not enough to submarine what I thought was a fairly interesting book…

“Lots of books are told “out of order”–and this book ends up being one of them unless you self-consciously figure out the chronology before actually reading (which I don’t see as a worthwhile thing to do). As it is, the chronology is not difficult to reconstruct retrospectively.”

To me, the nonlinear formatting didn’t seem necessary for a story that is, even if read nonlinearly, a really linear narrative. Unlike say Hopscotch or Composition No.1, Ware doesn’t at all problematize the basic linear story at the heart of Building Stories.

I feel bad talking about something that I haven’t seen (I’m starting to be part of the HU tradition, I guess), but anyways… The real question to me is: in what manner does the narrative justify the format? Or is Ware’s quixotic stand his only justification? (The Kramer’«s Ergot gigantic child is kinda… great… Anything else?

Derik…that’s fair…but Building Stories certainly wouldn’t be alone in telling a fairly linear story non-linearly.

I have absolutely no problem with choosing my own order to read the sections in. It’s the discomfort of reading some of the more awkward formats and the too small lettering that makes things difficult. It is hard to stomach people proclaiming the end of print or “floppies” or whatever. Bullshit. The addition of sound to film is a completely different thing than the change to digital format. Things can be done with a book that cannot be done in digital formats, and vice versa. There will always be books in some sort of form, unless these clowns go out and burn them all.

Kailyn: “If Ware was afforded the possibility to make the comics any size he wanted, why didn’t he print them closer to original size?”

The Ware originals for Building Stories are large (slightly bigger than twice up Silver Age art) but the lettering remain tiny. Not much relief. I think Ware rectified this (somewhat) in his later pages which are less packed with incident and narration.

The last paragraph presents a question, I have (in various contexts) suggested an answer:

Newspaper comics are a format or mode that exemplifies “unique to comics.” They are at once accessible, open to all social classes, transportable and provide a distinct reading experience that no other medium quite provides. Whether daily form or weekly in those Village Voice style papers. Somewhere between stand-up comedy and sit-down poetry. Somewhere between pulp narrative and momentary introspection.

The newspaper strip is subtle: it walks into our lives subtly and then we carry on our day. The newspaper strip is both transient and fully integrated into the larger activities of the user. Their magic is in how they seamlessly enter the reader’s life and exit without disturbing anything, yet allowing the reader to have a moment of levity, distraction, frustration, empathy…all between the local listings and the sports section.

xoxoxoxoxoxoxoxoxoxo

I have loved, loathed, hoorayed and hated Chris Ware at various points in the last decade or so. I have no qualms with him as a cartoonist. I do find something sad about his considerable talents going into this rather bizarre branch of the comics field which looks attractive but stands sort of outside of a cultural framework that could really benefit from it.

Not just Chris Ware, but just… again, since your essay floated the question.

To switch gears, taken as an excercise in “building stories” in terms of exploring the structure of narrative, the thing is very interesting. There are parts that DO fit or justify their presentation and there are innovative passages within. I guess I could prop the folding board up and reread it while eating my cereal, and it is handy that my copies of Quimby fit in the box too. Sure, I could lose the Bee comics in the couch cushions and not really miss them and I could dump the too-small golden book and slip the maybe only slightly bigger but still definitely more readable clipped-out pages from the NY Times magazine in the box instead. I do really like the new huge tabloid page sections and I can read them no problem! And, no one LIKES abortion. Looking again, Ware explores his character’s reaction to a traumatic experience that her boyfriend essentially bullies her into, pointing up that it should be HER choice. His handling of the physical problems of, and her feeling about others’ reactions to, her missing leg are quite well thought out.

So despite my reservations, the project is obviously worthwhile. I guess I do wish Ware, who can actually draw beautifully, would try drawing something in a different style soon—-he’s been doing this one for quite a while now (and I barely notice what Kailyn calls his Clowesian style). And for crying out loud cut the crap with the 2 point lettering, it’s a drag to have to struggle so much to see what I’m trying to read. Otherwise, perhaps the surrounding noise drowns out the quiet pleasures that can found in looking at and reading such intimate work.

Actually d&q published multi-story building model

http://drawnandquarterly.blogspot.ca/2012/10/multi-story-building-errata.html

Great article. You’re right even if those who hail BS are also right. There’s something very punk about comics, which some have corrupted as “you can make a movie with no budget!” Your example is Bechdel, mine would be Jeffrey Brown. I feel like some won’t want to go with this because part of the book is also that it costs $50–and wow, or whatever.

Pingback: » What’s In The Wonder Box

Pingback: » The Society of Saul Steinberg