This first appeared on Comixology

______________

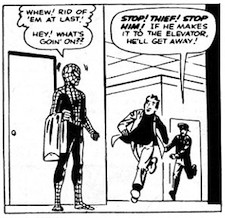

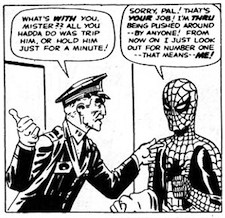

Spider-Man’s origin story, as most everybody knows, hinges on a moment of moral turpitude. In Amazing Fantasy #15 by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, nerdy, put upon Peter Parker, having been bitten by that pesky radioactive spider, gains (dum ta da!) super powers, and starts a successful career as a professional wrestler. Basking in his newfound fame and bucks, Peter (in Spidey costume) is standing in some random corridor when he sees some random schmo fleeing from a cop. Cop yells to Peter to stop schmo, but Peter refuses ; schmo gets onto high-speed elevator and escapes.

Spider-Man’s origin story, as most everybody knows, hinges on a moment of moral turpitude. In Amazing Fantasy #15 by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, nerdy, put upon Peter Parker, having been bitten by that pesky radioactive spider, gains (dum ta da!) super powers, and starts a successful career as a professional wrestler. Basking in his newfound fame and bucks, Peter (in Spidey costume) is standing in some random corridor when he sees some random schmo fleeing from a cop. Cop yells to Peter to stop schmo, but Peter refuses ; schmo gets onto high-speed elevator and escapes.

The cop chews Peter out, “All you hadda do was trip him”! Peter, though, is unrepentant: “Sorry, Pal! That’s your job! I’m through being pushed around!” Peter walks off and then on the next page his uncle is murdered! And two pages later, Peter learns that the guy who shot his uncle is the same guy he allowed to escape! Oh, the irony! Peter has learned too late that “with great power there must also come — great responsibility!”

Anyway, back to that moment of moral turpitude. What exactly is Peter’s failure here? The cop says that Peter should have tripped the guy or stopped him somehow. He even threatens to arrest Peter for failing to help. But… arrest him for what? Do citizens really have a legal obligation to throw themselves in the way of fleeing criminals? Do cops even really want citizens to throw themselves in the way of fleeing criminals?

On the contrary, if you’re a cop chasing a perp, the last thing you want is for some civilian in goofy red tights to get in the way. What if the perp has a concealed weapon (and in this case, we know that the villain did have a gun by the next page)? What if the civilian tackles the perp and then gets shot? What if the civilian tackles the perp and somebody else gets shot? At the very, very least, from a police perspective, that’s an exponential increase in paperwork.

Of course, we know that Spidey could have taken down the baddy without anyone getting killed or even hurt. We know this in part because he’s got super powers. Mostly though, we know it because — Duh! — he’s a super-hero, or even just a hero. Heroes like Spider-man or Batman or Dirty Harry leap into action and save people. That’s what they do. And if they didn’t do that, there wouldn’t be much of a story, would there?

Indeed, Spiderman’s real sin here is not against morality or society, but against the tropes that keep the genre afloat. Super-heroes have to act. They’ve got to fight crime. If they don’t, you don’ t have a narrative. Super-heroes have “great responsibility,” but it’s always the responsibility to do something. You could conceivably have an origin story in which Wombat-Man decked a baddy, the gun went off, Cousin Joe got shot, and the hero decided “With great power comes great responsibility!” And so Wombat-Man decides never to mess with crime again, and instead uses his phenomenal digging powers solely to aid with infrastructure projects! Again, you could have such an origin – but what you’d end up with would not exactly be a super-hero comic.

Indeed, Spiderman’s real sin here is not against morality or society, but against the tropes that keep the genre afloat. Super-heroes have to act. They’ve got to fight crime. If they don’t, you don’ t have a narrative. Super-heroes have “great responsibility,” but it’s always the responsibility to do something. You could conceivably have an origin story in which Wombat-Man decked a baddy, the gun went off, Cousin Joe got shot, and the hero decided “With great power comes great responsibility!” And so Wombat-Man decides never to mess with crime again, and instead uses his phenomenal digging powers solely to aid with infrastructure projects! Again, you could have such an origin – but what you’d end up with would not exactly be a super-hero comic.

In real life, of course, and as this suggests, the responsible, way to use your “great power” might conceivably in many circumstances be to sit on your ass and do nothing in particular. Certainly, if George W. Bush had done that in 2003, America and Iraq would both be a good bit better off today.

What I’m talking about here is essentially pacifism. Pacifism is about as massively discredited as a major philosophy can be. Pacifism is appeasement, or it’s treason, or, (more kindly) it’s a nice idea but not really practicable. You can’t just sit by and watch that guy escape, Spidey! Hit him! He’s got weapons of mass destruction!

I can’t say that I’m a pacifist myself, exactly. But I think that people can be way too quick to dismiss it, essentially because reality is rigged just like that Spidey origin story. For whatever reason, probably having to do with our reptile hind-brains and/or a steady consumption of revenge narratives, the negative consequences of inaction tend to seem to us infinitely more insupportable than the negative consequences of action. If we step aside and something bad happens, we say, “Oh no! I should have done more!” On the other hand, if you wade in and things get completely fucked up, you often feel like, “Well, at least I tried. And think how bad it would have been if we’d done nothing!”

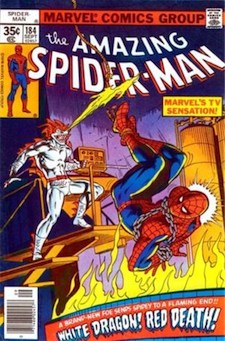

Which brings me to Amazing Spider-Man #184, published way back there in September 1978. My friendly neighborhood Internet tells me this was written by Marv Wolfman and drawn by Ross Andru. I must have read this when I was 8 or so; and I don’t think I even liked it all that much at the time. But I’ve remembered it all this time, in part because it is, rather bizarrely, one of the only super-hero comics I’ve ever seen that makes any effort to address either pacifism or the anti-pacifist assumptions at the core of super-hero comics. (The alternate-world Amish Superman in The Nail does not count. We will not speak of him again.)

Anyway, I haven’t seen ASM#184 in probably twenty years, but if memory (and a Web capsule summary) serves, the plot was a Bruce Lee rip off. Phil Chang is an awesome martial arts master, but he’s taken a vow of non-violence. Inevitably the evil Chinese gang wants him to join them. Their leader is the White Dragon, who is not only a martial artist extraordinaire, but also wears a white (natch) costume with a Chinese dragon style mask that looks staggeringly impractical, even by super-hero costume standards. Despite said mask, though, the Dragon is fully able to beat the tar out of the non-resisting Chang, and so he does – until Spidey comes to the rescue. Thank God someone is willing to fight, huh kiddies?!

That’s what you’d think the message would be anyway. In fact, though, Marv Wolfman’s script is surprisingly subtle. One exchange in particular has really stuck with me. I can’t quote exactly, alas, but to paraphrase, it went something like this:

Spidey: What in tarnation are you doing, anyway? The White Dragon is beating you to a pulp! He’s going to kill your family, you dope! Show me some of that kung-fu everyone’s been on about, won’t you? Are you a man or an amoeba? Come on, Phil! With great power comes great responsibility!

Phil: (and this I remember much better) There are failures in non-violence just as there are failures in violence.

I think that’s pretty profound. Yes, pacifism won’t necessarily solve all your problems. But then, fighting often doesn’t solve your problems either. Indeed, fighting can quite easily make things worse. You wouldn’t know that necessarily from reading super-hero comic books, of course — nor, perhaps, from public discourse in general. Which is why it might be worthwhile, sometimes, to remember that the power to right the world’s wrongs is given to neither man nor spider, and that we are all every bit as responsible for what we do as for what we don’t.

So what is pacifism? It is the uncompromising realization that we as humans are incapable of bringing about justice through violent retaliation. Hence, we relinquish all such acts to God in his sovereign and eschatological plan of judgment, justice, and mercy. Indeed, God have mercy on us.

—Mark Moore

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

if you’re a cop chasing a perp, the last thing you want is for some civilian in goofy red tights to get in the way. What if the perp has a concealed weapon (and in this case, we know that the villain did have a gun by the next page)? What if the civilian tackles the perp and then gets shot? What if the civilian tackles the perp and somebody else gets shot? At the very, very least, from a police perspective, that’s an exponential increase in paperwork.

————————-

That last line is hilariously brilliant…and so true!

Malory’s Morte Arthur is chock full of diverse demonstrations of the simple lesson that killing people is usually a bad idea.

(That’s all I got)

Only read bits here and there of Malory…but I think the Christian context is kind of important, right? There’s at least some value given to submission, and some discomfort with force as the solution to all problems. Also (perhaps unrelatedly), a certain narrative value/interest/romanticization/acceptance given to tragedy and failure. None of that is true in superhero stories, at least not for the most part.

Gundam Wing (anime series, but there’s also a manga: Battlefield of Pacifists) has a lot to say about pacifism as an ideology. Although it’s mostly that a small number of discredited people need to get their hands dirty to allow the majority to live in peace.

…Actually the main ideology of Gundam Wing is that war should be fought by a small number of highly trained professionals using really expensive hardware, and definitely never by robots or drones, which a friend calls “the ideology of a mecha anime director”. But anyway, there are a lot of speeches in-series about how to wage war “correctly” i.e. without killing off the 90% of humanity who live vulnerably in space stations.

Quite a few manga with pacifist and environmentalist themes, actually.

You could conceivably have an origin story in which Wombat-Man decked a baddy, the gun went off, Cousin Joe got shot, and the hero decided “With great power comes great responsibility!” And so Wombat-Man decides never to mess with crime again, and instead uses his phenomenal digging powers solely to aid with infrastructure projects! Again, you could have such an origin – but what you’d end up with would not exactly be a super-hero comic.

It’s funny you say this, because there actually was a superhero manga about rival construction companies: Jumbor, by the author of Shaman King. It didn’t do very well – canceled after 10 issues.

Wow; every manga plot really has been thought of.

I’m not as familiar with the manga conventions as with western superhero ones, so I’m leerier of trying to talk about how they fit precisely. But “small number of discredited people need to get their hands dirty to allow the majority to live in peace” is a pretty popular take on pacifism, both in genre and in real life. The assumption is that violence is more real than peace. I tend to think that that is less a description of how things “really” are than an ideological decision to *make* violence the default choice.

Great article. I’d never considered the position that Spider-Man was right to do nothing. Hell, doesn’t the act of not helping play to Ditko’s beliefs? Not that I know anything of objectivism besides how to mangle the spelling and instantly ignore anyone who starts a sentence “Y’know, that Ayn Rand…”

Ayn Rand was violently anti-pacifist, is my understanding. Ditko’s Mr. A was certainly into forceful intervention. So…I’m pretty sure Ditko felt that evil should be punished and good rewarded. I think the anti-pacifist implications here are probably more or less intentional.

You know that pacifism does not just imply “doing nothing” right? That many pacifists spend a lot of time and energy working on nonviolent direct actions against war to reconciliation and peacemaking activities, anti-violence intiatives, feeding the hungry, etc. etc. etc.? The idea that pacifism implies merely or only sitting still and letting someone beat you up is cartoonish, which is I guess appropriate for a Spider-Man comic but not for a serious discussion of pacifism.

Yes, of course there are lots of ways to think about pacifism, including very active non-violent resistance. But I think it’s pretty important for pacifism and non-violence to be willing to think about inaction and not committing violence as theoretically valuable.

It’s very difficult to get people to see that non-action and non-violence are a valid option. Nonviolent resistance can be a powerful force, but the fact is that many, many more lives would be saved than all the nonviolent resistance if the world if a handful of superpowers (ahem) simply refused to invade places. That’s not cartoonish; that’s as close to facts as we’re ever likely to get.

I haven’t been in a fistfight since I was about 10 or 11, and I don’t particularly like guns. However, in the military I shot “expert,” and I know I have the capacity to fight to the death if my loved ones or myself are threatened. I call that pragmatic pacifism.