Dystopias are always also utopias, just as hell always also implies a heaven. A blighted future is a warning, but it’s also a hope that the wrong-doers (if they do not repent) will finally, finally get theirs. Orwell’s 1984 broods luxuriously on the triumph of totalitarianism over all those who do not see as clearly as he. Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games revels in the voyeuristic exploitation bloodshed enabled by scolding us all for our voyeuristic exploitation jones. Disaster porn is — adamently, enthusiastically — porn, a sadistic/masochistic wallow in the end times. Grim visions are what we want to see; the rain of fire that scourges injustice — or, sometimes, that just scourges. Because scourging is fun.

Alun Llewellyn’s 1934 sci-fi dystopia, The Strange Invaders presents a particularly complex apocalypse — and, ergo, a particularly complex set of apocalyptic desires. The story is set in a far future earth, where a combination of nuclear holocaust and oncoming ice age have knocked humanity back to the middle ages. The action is centered in a factory town of the former Soviet Union, now a holy city, inhabited by a people called the Rus. The Rus worship a Trinity — Marx, Lenin, Stalin — who they only vaguely understand. Church Fathers rule over a military class of Swords, who keep the peasants in line scraping out a subsistence existence.

This already-quite-grim-thank-you world is plunged into chaos as nomadic Tartars begin fleeing to the Rus’ holy city from the South, seeking shelter. They claim to be pursued by giant, man-eating lizards. The Church Fathers at first don’t believe it (Marx said nothing about giant man-eating lizards!) and so order the Swords and the peasants to massacre the Tartars before they eat too much of the food supply. Soon after the deed is done, though,the saurians show up and set about killing just about everyone they can get their talons on. Finally, in a War-of-the-Worldsish stroke of luck, winter comes in and for some reason the in-all-other-ways evolutionarily perfect lizards are unable to sense the temperature drop soon enough, and go dormant, allowing the few remaining humans to slaughter them. This isn’t exactly a happy ending, though; humans are now trapped between the lizards to the south and advancing glaciers to the north, and while there may be a respite for our particular band of the Rus, humanity’s long-term outlook seems awfully dicey as the book closes.

In his book Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction, John Rieder reads The Strange Invaders along a number of allegorical lines. First, he notes that it maps and reverses the traditional lines of imperialism; instead of a vigorous northern European invasion of the decadent Southern periphery, Llewellyn presents a vital South launching an attack on the decadent, etiolated north.

I don’t necessarily disagree with Rieder’s take here…but I think it’s important to take into account the fact that this is not just any north we’re talking about here, but Russia in particular. Obviously, the Cold War was not underway in 1934 — but Llewellyn (according to Brian W. Aldiss’ preface) had actually visited the Soviet Union, and appears to have had a better sense of its problems than many of his contemporaries. In any case, there’s no doubt that the northern weakness here is a particularized Russian weakness. The blind obedience to authority, the inflexibility, and the cruelty of the Rus is linked specifically by Llewellyn to Communism.

It was a tale often told, a moral often preached. They had sinned; all mankind had sinned. Marx from whom the world had received the blessing of the Faith had remade the world in a plan of Five years…. The faith had been wronged and the Destruction was the vengeance enacted. Therefore must the faith be honoured strictly by those that survived, and they must to that end give obedience unquestioning, surrender thought and spirit and body to their rulers who were guardians of that faith.

Rieder of course appreciates the satirical fillip (now perhaps rendered into almost a commonplace of anti-communism) of turning the resolutely materialist Marx into a deity. But he never quite links the Russian context to the discussion of peripheries. If one does so, the novel becomes a parable not so much of reversing center and margin, but rather of wars on the margins — of Russia, perhaps, being devoured by its own atavistic, subservient Orientalist weakness.

From this perspective, then, the saurians and the Russ are not in opposition, but are on a continuum. And in fact, there is a fair bit of textual support for the idea that the giant lizards are not the death of the Rus, but their perfection. The ideal of the Rus is unthinking obedience; direction without will. Adun, the protagonist, is caught between his human desires and his society’s demand that he become merely the tool of the Fathers — a kind of machine, like those left in the factory/church and worshiped. “The Fathers and the men they kept to uphold them were not to be questioned,” Adun thinks to himself. “Mind and body they commanded, as the Faith directed. He was nothing. He dared do nothing.” (18)

If Adun has to convince himself to become an object, the giant lizards have no such problems. As Rieder notes, the creatures “hover on the uncanny border between the organic and the mechanical.” In one of the most striking passages of the novel (which Rieder quotes), the creatures are envisioned as a depersonalized collective; a single coherent unity of force.

The plain, where it came down from the river, was alive with inter-weaving movement. They played together in the sun as though its brightness made them glad, running over and under one another, swiftly and in silence, but with an almost fierce alacrity, eager and unhesitating, unceasing. The eye was not quick enough to catch the motion of their rapid, supple bodies that seemed not to move with the effort of muscles but to quiver and leap with an alert life instinct in every part of them. They were brilliant. As he looked, Karasoin saw the play of colour that ran over those great darting bodies, a changing, flashing iridescence like a jewelled mist. Their bodies were green, enamelled in scales like studs of polished jade. But as they writhed and sprang in their playing, points of bronze and gilt winked along their flanks and their throats and bellies as they leaped showed golden and orange, splashed with scarlet. Now and then one would suddenly pause and stand as if turned to a shape of gleaming metal, and then they could see plainly its long, narrow head and slender tail and the smoothly shining body borne on crouching legs that ended in hands like a man’s with long clawed fingers; five.

This is the awesome fulfillment of Ronald Reagan’s “ant heap of totalitarianism.” Stalinism is here embodied not by the proletariat, but by those even below them, the lizards forged into a remorseless, infinitely flexible machine-state. The blind watchmaker forges the revolution, and thus Marxism for Llewellyn will literally, and beautifully, eat itself.

Again, though, just because the lizards are the ultimate totalitarians doesn’t mean that the humans are somehow battling totalitarianism. In 1984, Big Brother is schematically opposed to the human emotions of love, friendship, warmth, and sex. Llewellyn’s vision is less pat. Adun’s love, not to mention his sexual desire, does in fact inspire his resistance to the regime of the Fathers. But that resistance isn’t exactly idyllic. On the contrary, Adun’s passion for the hardly-characterized Erya is almost inseparable from his own pride and desire for power. At one point he threatens (and it is not an idle threat) to kill her if she chooses the captain of the Swords, Karasoin — a murder-lust echoed by his participation in the genocidal slaughter of the Tartars within the city walls. Eventually, Adun does win Erya…by murdering Karasoin after the Sword almost rapes her. Thus, the alternative to mechanized, unfeeling destruction is not love or peace, but rather the cthonic, feeling bloodshed of jealousy, rage, and rape-revenge.

Llewellyn is willing to suggest other possibilities. Erya, for example, has a vision of independence and freedom — though that’s eventually crushed by the ongoing crisis which requires her to get a man for protection or else. Karasoin, before he actually rapes Erya, is ashamed and decides not to attack her — just in time for Adun to hack him apart. And at the book’s end, Adun’s brother Ivan speaks haltingly of the need for men to stop killing each other…and then, of course, he dies of his wounds.

The novel’s flirtations with peace, then, are all cynically inflected; they are raised to be shot down in a frisson of pathos and irony. Both the lizards and the rape-revenge narrative, on the other hand, have a visceral, awful appeal. The beautiful, terrible new force which will inherit the earth; the beautiful, terrible old force that has held the earth: they rush upon each other, soundless or howling, and from their writhing, bloody struggle there rises genre pleasures, old and new — violence, lust, apocalypse, the cleansed earth and the pleasure of watching its filthy cleansing. The Strange Invaders is a bitter reversal of imperialism, a prayer for a more perfectly genocidal imperialism, and — to the extent that its vision is enacted on and powered by Orientalist tropes — arguably an act of imperialism itself.

The final twist of the novel is, perhaps, that, despite its prescient and honorable anti-Stalinism, its apocalyptic vision is ultimately not apocalyptic enough. The saurians, in all their awesome power, and the humans, for all their ugly narrow-mindedness, can neither compare with the power, the ugliness, or the narrow-mindedness of what can’t really compare with the atrocities Stalin was perpetrating while Llewellyn was writing his book. The gigantic force of the state, wielded by a jealous, paranoid madman, was able to generate a holocaust in the Ukraine, and throughout Russia, that makes Llewellyn’s bleak vision — shot through with beauty and with joy at the bleakness — seem positively naive. That’s not Llewellyn’s fault exactly, though. History, indifferent alike to justice and desire, will always be grimmer than dystopia.

“Passers-by no longer pay attention to the corpses of starved peasants

on a street in Kharkiv, 1933.”

“A blighted future is a warning, but it’s also a hope that the wrong-doers (if they do not repent) will finally, finally get theirs.”

Wouldn’t the Book of Revelations be the original dystopia?

Not sure about original; there are pre-Revelations apocalyptic texts. But I think it’s an example of what I’m talking about, yeah.

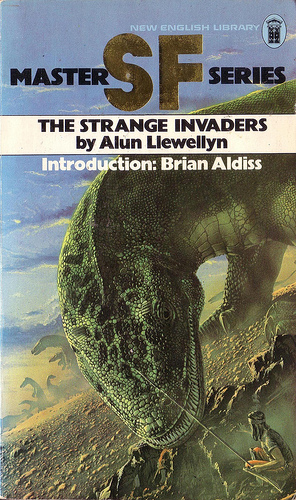

Strange Invaders is an interesting choice for a post. Were you planning to write about it for awhile, or did you just pull it off the shelf because of those awesome giant lizards on the cover?

That would be “neither.” I ordered it from Amazon thinking it was a different book, believe it or not (I got confused flipping through John Rieder’s study and searched the wrong title.) But I figured I’d read it anyway….

Had you heard of it before? My impression is that it’s pretty obscure, but maybe I’m wrong about that…?

It is pretty obscure, from what I can tell. I’d never heard of it but I do remember seeing the cover somewhere … though maybe I’m mistaking it for another dystopian tale with giant lizards.

So if Llewellyn was writing in the 1930s, then he must have been one of the first writers working in the post-apocalyptic barbarian genre.

Again, not exactly sure he’s a first…from Rieder’s account, though, there were a number of imaginings of post apocalypse at the time, often tied in one way or another to Britain’s decolonialization….

Your take is nice– history is more depressing than fiction– sort of like Agamben’s thing about how there is no poetry after the Holocaust or whatever, but it could apply to the Crusades or the Congo just as easily.

Also– I want to split hairs about apocalypse and post-apocalypse. 1984 and its ilk are depictions of the eternal present, as is Strange Invaders. Proper apocalypse is always yet-to-come, with pretty different implications for ethics and such.

Hmmm…is that a theological distinction? I don’t think that’s normal secular use necessarily. That is, post-nuclear war stories like Strange Invaders are usualy referred to as post-apocalyptic…

Right. I’m agreeing that Strange Invaders, 1984, etc. are post-apocalyptic, whereas Revelations &c. are forward-looking apocalypses. Terminator is a nice conflation of those categories.

Ah, okay.

Anyone want to defend 1984, I wonder? I haven’t read it in a long time…but it sure hasn’t aged well in memory at least….

Defend it against what? It seems to fit communism pretty well. It’s not any better than We, though.

Bert, i believe you mean Adorno.

Oh, neo-Marxist European A-names always throw me.

The film version of 1984 is fantastic– because it’s all about atmosphere over allegory.

I’ll grant it’s a beautiful turd of a film.

It fits communism fine. It’s take on humanism, though, is stupid.

this book sounds dope as hell

I think I like it more after writing this review and thinking about it some. The high concept and the writing (especially the descriptions of the saurians) are first rate; characters are blah and not really distinctive; many of the plot details are kind of generic. So my reaction was kind of mixed…though the good parts are really good. It’s definitely worth reading.

Hmm, Noah, I don’t really consider it a particularly humanistic work (yes, Orwell supports some humanistic values himself, but the book is extremely skeptical of such values winning out — that’s not exactly the humanism of a Burgess, for example), and I can’t imagine you ever defending humanism, so I’m not sure what you’re getting at. I consider it one of the best works of SF or literature I’ve probably encountered. I love the sex stuff in it. And it’s had lasting effects on the way we view the world — most books can’t claim that, even some of the best ones. But, really, does fucking 1984 have to defended on its merits? Maybe if you attacked it more, I could muster the energy.

Wow…you’re a huge fan of 1984. I am duly disoriented.

I guess it has had lasting effects, but I think quite possibly mostly for the worse. It’s anti-Communism is actually very easy, alas — and its (and Orwell’s general) self-righteousness often seems like it’s used to justify a vision of our enemies as uniformly and indistinguishably evil. You sort of do it yourself with the claim about Communism. Orwell’s novel is a fair description of Stalin and Mao, perhaps (you can’t really paint them as evil enough), but in terms of other communist regimes…eh. Khruschev wasn’t a monster; the regime in China isn’t irredeemably evil.

I think Orwell is arguably actually smarter than that in some ways, though (you could argue that he’s saying that Communism and the capitalist countries are equivalent for example.)

Orwell romanticizes human individuality, love, and sex; I think it’s pretty recognizably in a tradition of English small-hero nostaliga. The fact that those virtues are crushed isn’t exactly a refutation of the tropes; conservatism generally gets its emotional power from yearning for a lost past, so the fact that the past is lost isn’t an especially original twist. As I said in the review, I think Llewellyn is more convincing; there isn’t any refuge in the past in The Strange Invaders, and sex is no salvation — not even a temporary one.

The work has been completely repurposed for Capitalistic-Democratic societies though. So high school kids in Singapore, for example, can sometimes be made to see that they’re living in a semi-Orwellian society. Same for the U.S. presumably.

You’d like to think so. But the highest profile Orwellites (like Hitchens and Andrew Sullivan) used his work as an excuse to bomb the shit out of islamofascism.

Okay, if you’re sympathetic to all the antihumanistic tendencies of pomo and whatnot that occurred in the late part of the 20th century, then you’re not going to care for 1984. I gotcha. I think he’s pretty much right, and most postmodernism would only lead to totalitarianism if it ever had caught on in any meaningful way. Yeah, we have a self, we have individuality, we are capable of free thought. Orwell’s views were hard earned, I believe, and just because he was proven right, it hardly lessens their value now. It wasn’t like all his fellow leftists were just going, “oh, we all knew that already, George.” There was a good deal of resistance to critical examinations of really existing leftism from leftists (it took 80 years for We to be published in Russia). I do think there are many flavors of totalitarianism, and 1984 and We are just one aspect of it, but clearly it’s a realistic depiction of what could happen. Just the expressed fear of a totally controlled, socially constructed past should give most a pause. The use of language, while not being a reductionist about language is much more subtle than your average deconstructionist would have it. Orwell really understood the dangers of constructing reality to fit an ideal. It’s not just relevant to communism. That’s just off the top of my head.

“Khruschev wasn’t a monster; the regime in China isn’t irredeemably evil.”

As long as you went along with Ingsoc and didn’t fuck up too badly (or aren’t judged to have fucked up too badly), it wasn’t irredeemably evil, either. People were living just fine under it. It was only when someone began to break out of its regimented thought patterns, that the evil really manifests itself. It’s not exactly a Stalinist purge being depicted in the book.

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

In one of the most striking passages of the novel (which Rieder quotes), the creatures are envisioned as a depersonalized collective; a single coherent unity of force.

…They played together in the sun as though its brightness made them glad, running over and under one another, swiftly and in silence, but with an almost fierce alacrity, eager and unhesitating, unceasing….Now and then one would suddenly pause and stand as if turned to a shape of gleaming metal, and then they could see plainly its long, narrow head and slender tail…

This is the awesome fulfillment of Ronald Reagan’s “ant heap of totalitarianism.” Stalinism is here embodied not by the proletariat, but by those even below them, the lizards forged into a remorseless, infinitely flexible machine-state.

————————

If that was Rieder’s conclusion, it’s certainly an absurd one. There’s nothing in that passage to indicate unified, purposeful collective action such as ants exhibit in breaking up a carcass for food or rebuilding their smashed nest; this is merely a group of animals lounging and occasionally gamboling in the sun.

Someone with “ideology vision” could likewise look at a group of otters sunning by the water and splashing playfully and see “the ultimate totalitarians,” a sinister Borg-like collective…and it would be just as absurd.

————————

Bert Stabler says:

The film version of 1984 is fantastic– because it’s all about atmosphere over allegory.

————————–

Which one? I’d imagine you’re referring to the more recent John Hurt version, which I’ve not seen, though; certainly nothing atmospheric about the old b&w film…

—————————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

The work has been completely repurposed for Capitalistic-Democratic societies though. So high school kids in Singapore, for example, can sometimes be made to see that they’re living in a semi-Orwellian society. Same for the U.S. presumably.

—————————-

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

You’d like to think so. But the highest profile Orwellites (like Hitchens and Andrew Sullivan) used his work as an excuse to bomb the shit out of islamofascism.

—————————–

Suat’s argument is perfectly correct, rather than a foolish “you’d like to think so” self-delusion. Reading “Nineteen Eighty-Four” and the totalitarian machinations, propaganda techniques so satirized…

——————————

During one particular Hate Week, Oceania switched allies while a public speaker is in the middle of a sentence, though the disruption was minimal: the posters against the previous enemy were deemed to be “sabotage” of Hate Week conducted by Emmanuel Goldstein and his supporters, summarily torn down by the crowd, and quickly replaced with propaganda against the new enemy, thus demonstrating the ease with which the Party directs the hatred of its members.

——————————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hate_week

…plus…

——————————-

Many of its terms and concepts, such as Big Brother, doublethink, thoughtcrime, Newspeak, and memory hole, have entered everyday use since its publication in 1949. Moreover, Nineteen Eighty-Four popularised the adjective Orwellian, which describes official deception, secret surveillance, and manipulation of the past by a totalitarian or authoritarian state.

———————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nineteen_Eighty-Four

…makes one more aware, sensitized to that crap happening in other contexts. Who can hear the Bush administration’s avowal, when no WMD’s turned up in Iraq, that it actually invaded “for Freedom” and not think of how “Oceania switched allies while a public speaker is in the middle of a sentence”? Did not Bush II’s plan for the Healthy Forests Initiative, actually planned to facilitate clear-cutting by timber interests, and the “Clear Skies Initiative” — which actually lowered pollution standards ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Clear_Skies_Act_of_2003 ) — reek of “freedom is slavery” and such from Orwell?

Thus, rather than simply imparting a “Communism is Evil” message (far better given by the more explicitly targeted “Animal Farm”), “Nineteen Eighty-Four” is against totalitarianism. That the regime is a “political system euphemistically named English Socialism” hardly makes it far-leftist; the Nazis were “nationalist socialists.”

And that some dumbasses “used his work as an excuse to bomb the shit out of islamofascism” or “it’s used to justify a vision of our enemies as uniformly and indistinguishably evil” hardly damns the work itself; Jesus has been used to justify mass murder, torture, smug moral condemnation of others, accumulation of wealth, etc.

You really think that 1984 is realistic. I’m…I guess a lot of people do, maybe, but that’s just silly. The state is too competent by a lot. People just aren’t that competent. Much of the evil is done because of that.

China today just isn’t Big Brother. It’s a state with lots of problem and lots of injustices (some of them pretty horrific.) But it’s not a psychopathic abattoir, and it doesn’t control people’s lives with anything like the thoroughness you see in 1984 — and doesn’t even want to control them that way. 1984 is a fantasy and an exaggeration. That’s not a problem in itself…but taking it as realistic is kind of nutty (though maybe you were just hyperbolizing…?)

The difficulty in separating ideology and individuality is that individuality is (especially in our time) its own oppressive ideology. Orwell’s conservative nostalgia is used for authoritarian political ends every bit as often as any other ism. The state doesn’t have a monopoly on sin.

I did mean the John Hurt movie. And Hitchens certainly gives Orwell a lot to answer for.

First, this sentence of mine makes no sense: “The use of language, while not being a reductionist about language is much more subtle than your average deconstructionist would have it.” What I meant was that Orwell was able to show how language can shape reality without being a determinist about it, something that isn’t true of most deconstructionists.

Second, yes, I think Orwell gave us a fairly realistic version of ideals that were being expressed by utopianists. And while it might be true that the government would always be more incompetent than what he showed, he does show some incompetence (the way Winston sees the changes to the past being made), but that it doesn’t matter so much as long as most people go along with it. I’d question whether living under Big Brother is really any worse than living in North Korea. I think I might prefer the other. That’s enough to suggest ‘realistic’ isn’t that hyperbolical.

Third, I’d rather live in modern day China, too, but Maoism as a dream had something like 1984 as a reality. I remember this Canadian woman discussing her memoirs on an NPR show once. She was a 60s radical, but really committed, having moved to mainland China to learn what it was like. She couldn’t ever trust sharing any feeling of doubt or whatever with neighbors or friends, because everyone was a likely informant (informing might get your family extra rations). Truly a paranoid society at the time. I think 1984 evokes that feeling really well … frighteningly well. Thus, the affect is very realistic, too.

Orwell had a good grasp of totalitarian thinking, much better than most. (We actually captures tendencies in capitalism, particularly the commodification/reification of man, much better. The only thing that lessened my view of 1984 was to see how much Orwell borrowed from Zamyatin.)

The John Hurt version really does look great, but damn if it isn’t a misery to sit through.

Does anybody else find it sadly amusing/amusingly sad that the term “Big Brother” is probably more associated with a shitty reality TV show these days than with Orwell?

Sorry, that’s all I’ve got to add to the discussion. I like 1984, but it certainly doesn’t seem “realistic”. The concepts are pretty powerful though, which is why so many of the terms Orwell coined, as well as the word “Orwellian” are so persistent.

Going along with my 2nd point above, it’s an interesting situation Orwell created: memory and history needs the affirmation of the present, while not slipping into the view that the past is merely a construction.

Matthew, I think that could be called anticipatory conformity: getting people used to the idea of Big Brother surveillance through entertainment.

Just to clarify Noah’s point as I have psychically appropriated it– the real utopia in Orwell is not the workers’ utopia, it is the author’s utopia. Struggling writer, bravely confronting but then being sublimely consumed by the pathos of the big Other.

Yes, that’s the point. 1984 isn’t just a warning; it’s a wish for the world to be consumed so that the righteous can be lauded for their prescience. That’s (part of) how dystopias work. And it’s not unrelated to the way in which Orwellism has become a major thread in the ideology of imperial violence.

yeah, that’s pretty fanciful. you can apply the same rationale to any critical take on anything. patriarchy is the feminist utopia, their wish to be sublimely consumed by the phallus. people like to be right about their opinions. that’s hardly a criticism of orwell.

———————

Noah Berlatsky says:

You really think that 1984 is realistic. I’m…I guess a lot of people do, maybe, but that’s just silly. The state is too competent by a lot. People just aren’t that competent. Much of the evil is done because of that.

———————

Ah, the classic “accuse somebody of making some outrageous/absurd statement which they in fact did not make, then attack them for making an outrageous/absurd statement” tactic!

I wrote, “Reading “Nineteen Eighty-Four” and the totalitarian machinations, propaganda techniques so satirized…” (Emphasis added)

Alas, however, reality has a way of making even exaggerated satire (“Oceania switched allies while a public speaker is in the middle of a sentence”) seem too modest. How about the tens of millions of Fox News watchers who seriously believe Obama is an atheist Muslim who wants to impose Sharia law and gay marriage and abortions? We’re not talking of smoothly switching from one ally to another, here are ludicrous contradictions eagerly embraced.

And your big reason for not finding Orwell’s book “realistic” — so it’s a fantasy, then? — is because “the state is too competent by a lot”?

Why, 99.999% of literature and film must be likewise dismissed as “unrealistic,” if one is to apply utterly factual standards, statistics, and such to them.

———————

Bert Stabler says:

….Hitchens certainly gives Orwell a lot to answer for.

———————-

Not any more than if Swift’s “A Modest Proposal” would have led a Brit to take it seriously, and eat an Irishman.

———————–

Matthew Brady says:

Does anybody else find it sadly amusing/amusingly sad that the term “Big Brother” is probably more associated with a shitty reality TV show these days than with Orwell?

———————–

Now that you mention it, yes. At least we can be glad that eventually ratings will peter out, the TV show will be canceled and forgotten, while “Nineteen Eighty-Four” will remain a classic.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Yes, that’s the point. 1984 isn’t just a warning; it’s a wish for the world to be consumed so that the righteous can be lauded for their prescience. That’s (part of) how dystopias work. And it’s not unrelated to the way in which Orwellism has become a major thread in the ideology of imperial violence.

————————–

————————–

Charles Reece says:

…you can apply the same rationale to any critical take on anything. patriarchy is the feminist utopia, their wish to be sublimely consumed by the phallus…

—————————

Ha! Well, now that you mention it…

Seriously, though; so the argument is that writers of dystopias want the horrible scenarios they describe to come true, so they’ll be “lauded for their prescience”? Even though they’ll suffer along with everyone else when those dreadful predictions come to pass?

One can see an inmate in a Nazi gas chamber, arrogantly preening as the Zyklon B is poured in: “Now do all of you appreciate how brilliantly right I was in warning about what anti-Semitism would lead to?”

Why not limit it to dystopias; would not someone warning that “if this goes on, disastrous consequences will happen” in a nonfictional fashion then be delighted when the stalking, threatening ex-husband finally goes ahead and kills them, when the appealing-to-the-insecure-masses “Escape from Freedom” Erich Fromm brilliantly warned of ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Escape_from_Freedom ) is taken by the citizens of Nazi Germany?

And as to whether “Nineteen Eighty-Four” is realistic or unrealistic, of course it’s both. It’s easy to forget that it’s a sort of science fiction book, set decades into the future, both grounded in realities of human behavior and existing totalitarian regimes and their mind-controlling tactics, and extrapolating — as SF, rather than fantasy, does — technologies and tactics into imaginary realms, often with satiric exaggeration. (I’ll never forget Orwell’s “pornovac,” a type of computer to crank out written porn. Surely such a program could be produced these days; just plug in your favorite fetishes and click on the desired parameters…)

Looking up “orwell 1984 as science fiction,” ran across this “REVIEW OF 1984” by one of the greats of SF, Isaac Asimov. As befits his brilliant intellect (Asimov was a scientist as well as SF writer), it’s laden with perceptions. He points out how Orwell specifically targeted Communism rather than Nazism, gives credit for prescience where due, notes how

—————————-

In 1984 every shift of alliance involved an orgy of history rewriting. In real life, no such folly is necessary. The public swings from side to side easily, accepting the change in circumstance with no concern for the past at all. For instance, the Japanese, by the 1950s, had changed from unspeakable villains to friends, while the Chinese moved in the opposite direction with no one bothering to wipe out Pearl Harbour. No one cared, for goodness’ sake.

—————————–

…amusingly details how Orwell was not much of an SF writer, in strokes both broad…

—————————–

Orwell imagines no new vices, for instance. His characters are all gin hounds and tobacco addicts, and part of the horror of his picture of 1984 is his eloquent description of the low quality of the gin and tobacco.

He foresees no new drugs, no marijuana, no synthetic hallucinogens. No one expects an s.f. writer to be precise and exact in his forecasts, but surely one would expect him to invent some differences.

…Nor did he foresee any difference in the role of women or any weakening of the feminine stereotype of 1949…

—————————–

and hilariously niggling:

—————————–

…when his hero writes, he ‘fitted a nib into the penholder and sucked it to get the grease off. He does so ‘because of a feeling that the beautiful creamy paper deserved to be written on with a real nib instead of being scratched with an ink-pencil’.

Presumably, the ‘ink-pencil’ is the ball-point pen that was coming into use at the time that 1984 was being written. This means that Orwell describes something as being written’ with a real nib but being ‘scratched’ with a ball-point. This is, however, precisely the reverse of the truth. If you are old enough to remember steel pens, you will remember that they scratched fearsomely, and you know ball-points don’t.

——————————-

How nerdily nitpicky can you get?

Anyway, the delightful whole at http://www.newworker.org/ncptrory/1984.htm …

Isn’t it a bit strange to fault 1984 for it’s characterization of communist regimes by saying that those of Khrushchev and modern China aren’t nearly as bad when the book was actually written in the time of Stalin and Mao?

That might make it less relevant as those regimes mellowed but to me its seems that the main point that has stuck with us isn’t the bleak communistic vision of central planning and oppression but the manipulation of language that’s just as applicable to modern liberal states.

Charles, people do like to be right about their opinions…but Orwell is pretty smug, I’d say. As I said in the review, Llewellyn, for example, is a lot less sanguine about the vision of an idealized human individuality. He paints things much less black and white.

And feminism has plenty of problems with idealization of the patriarchy in various ways. But…lots of feminism isn’t particularly utopian, but is focused on tactical issues. I think you’re missing the ways in which this is a particular issue with utopia — and also downplaying the extent to which the human desire to be right links up with the human impulse to violence and intolerance. Orwell’s smugness is fairly central to what he’s doing.

Ormur, that’s a reasonable point about Khruschev. I’d say it’s more of a problem for followers of Orwell perhaps, who would do well to make distinctions and realize that the dystopia he predicted didn’t actually happen, and to think about what that means for its realism (or lack thereof.)

Again, it would be nice to believe that folks could apply Orwell to our own society. In practice, though, he’s been deployed most frequently and forcefully in recent years to justify bombing the other guy — which, as I said, I think is somewhat enabled by his schematic morality and general self-vaunting.

Noah, if you think the boring humanist take on Orwell is arrogant, you should read Richie Rorty’s essay on him from Contingency, Irony, Solidarity. Whole different ball game.

Also, if we’re pointing fingers at humanists, I think your assertion that “people just aren’t that competent” is some pretty broad armchair universalizing. Maybe you prefer the Huxley version where we breed ’em totalitarian. I always found that more compelling anyway.

I’m comfortable with the assertion that people aren’t perfect. If there’s one truth about human nature, I think that would be it.

Marx actually mentions how there’s sort of a dominant economic zeitgeist to an era– like, during the agrarian Middle Ages, even artisans used a basically home-based agricultural style of production, while during the industrial era, agriculture becomes another mass-production industry.

All that just to say that humanism borrowed from adventure and romance in the early days of the novel, but that it would borrow from utopian literature is hardly surprising. Especially given that humanism is all about the transparency, autonomy, and originality of its empty center. Goes great with capitalism!

And I don’t totally hate capitalism or humanism, but Orwell is hardly an improvement on Swift, just an update.

I like Swift a lot more than Orwell. He’s a ton weirder. You don’t find Orwell recommending eating babies.

Orwell’s kind of humorless and uptight. He can do scorn or ridicule, but absurdity is largely beyond him, at least as far as the writings I’ve read. Even Animal Farm is remarkably uncontaminated by caprice.

Orwell did come up with the great line “All animals are created equal, but some are more equal than others” though. I like the dryness of that one.

Yeah; he’s got a real way with a slogan. There’s a certain irony to that.

I do like his prose. To Shoot an Elephant is fantastic, and parts of Animal Farm will break your heart. I just feel like he’s overhyped…not even as a writer, necessarily, but as a moral paragon.

You note that 1932 is before the Cold War, but it’s also a good time before the atom bomb – does the book really mention “nuclear holocaust”?

I apologise for bothering you about small details, but 1932 seems like a fascinatingly early time to be predicting universally destructive nuclear exchanges between the superpowers, unless I’m more ignorant of 1930’s science fiction than I though I was. I know London wrote of bacterial warfare as early as 1910, but that was hardly post-apocalyptic in genre…

No apology necessary. That’s a great point.

I don’t think it does actually mention nuclear holocaust specifically. Just some sort of catastrophe that seems linked to war. There’s also the implication that humans are having trouble reproducing, which I just linked to nuclear fallout…but Llewellyn could quite possibly have been referring to biological disaster.

So, yeah, I think it’s just prescient enough to suggest nuclear holocaust very strongly to our present day, but that’s almost certainly not what Llewellyn himself was thinking.

——————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

…I just feel like he’s overhyped…not even as a writer, necessarily, but as a moral paragon.

———————–

Fair enough! And as a human being, he could certainly be a jerk, unconcerned about putting friends through hardship and mortal danger in a misguided boating expedition. Details on this article about his diaries at http://harpers.org/archive/2012/10/double-vision/ .

In “Honest, Decent, Wrong — The invention of George Orwell,” we read:

———————–

“Animal Farm,” George Orwell’s satire, which became the Cold War “Candide,” was finished in 1944, the high point of the Soviet-Western alliance against fascism. It was a warning against dealing with Stalin and, in the circumstances, a prescient book.

…Frances Stonor Saunders, in her fascinating study “The Cultural Cold War,” reports that right after Orwell’s death the C.I.A. (Howard Hunt was the agent on the case) secretly bought the film rights to “Animal Farm” from his widow, Sonia, and had an animated-film version produced in England, which it distributed throughout the world. The book’s final scene, in which the pigs (the Bolsheviks, in Orwell’s allegory) can no longer be distinguished from the animals’ previous exploiters, the humans (the capitalists), was omitted. A new ending was provided, in which the animals storm the farmhouse where the pigs have moved and liberate themselves all over again. The great enemy of propaganda was subjected, after his death, to the deceptions and evasions of propaganda—and by the very people, American Cold Warriors, who would canonize him as the great enemy of propaganda.

Howard Hunt at least kept the story pegged to the history of the Soviet Union, which is what Orwell intended…But although Orwell didn’t want Communism, he didn’t want capitalism, either. This part of his thought was carefully elided, and “Animal Farm” became a warning against political change per se. It remains so today. The cover of the current Harcourt paperback glosses the contents as follows:

“As ferociously fresh as it was more than half a century ago, ‘Animal Farm’ is a parable about would-be liberators everywhere. As we witness the rise and bloody fall of the revolutionary animals through the lens of our own history, we see the seeds of totalitarianism in the most idealistic organizations; and in our most charismatic leaders, the souls of our cruelest oppressors.”

This is the opposite of what Orwell intended. But almost everything in the popular understanding of Orwell is a distortion of what he really thought and the kind of writer he was.

Writers are not entirely responsible for their admirers. It is unlikely that Jane Austen, if she were here today, would wish to become a member of the Jane Austen Society. In his lifetime, George Orwell was regarded, even by his friends, as a contrary man. It was said that the closer you got to him the colder and more critical he became. As a writer, he was often hardest on his allies. He was a middle-class intellectual who despised the middle class and was contemptuous of intellectuals, a Socialist whose abuse of Socialists—”all that dreary tribe of high-minded women and sandal-wearers and bearded fruit-juice drinkers who come flocking toward the smell of ‘progress’ like bluebottles to a dead cat”—was as vicious as any Tory’s…the works for which he is most celebrated, “Animal Farm,” “1984,” and the essay “Politics and the English Language,” were attacks on people who purported to share his political views…

Orwell’s army is one of the most ideologically mixed up ever to assemble. John Rodden, whose “George Orwell: The Politics of Literary Reputation” was published in 1989 and recently reprinted, with a new introduction (Transaction; $30), has catalogued it exhaustively. It has included, over the years, ex-Communists, Socialists, left-wing anarchists, right-wing libertarians, liberals, conservatives, doves, hawks, the Partisan Review editorial board, and the John Birch Society: every group in a different uniform, but with the same button pinned to the lapel—Orwell Was Right. Irving Howe claimed Orwell, and so did Norman Podhoretz. Almost the only thing Orwell’s posthumous admirers have in common, besides the button, is anti-Communism.

…Orwell spent the first half of 1937 fighting with the Loyalists in Spain, where he was shot in the throat by a fascist sniper, and where he witnessed the brutal Communist suppression of the revolutionary parties in the Republican alliance. His account of these events, “Homage to Catalonia,” which appeared in 1938, was, indeed, brave and iconoclastic (though not the only work of its kind), and it established Orwell in the position that he would maintain for the rest of his life, as the leading anti-Stalinist writer of the British left.

—————————

Emphases added; much more at http://www.newyorker.com/archive/2003/01/27/030127crat_atlarge#ixzz2Dni7YH5b

See, also: http://www.newyorker.com/online/blogs/bookclub/2009/04/reading-orwell-george-packer.html

One thing Llewelyn seems to have dealt with more straightforwardly if less subtly than Orwell was the idea of State as religion. But the idea that there could be an omnipotent institution on Earth is truly a hallmark bogey of Enlgihtenment/humanist discourse. It’s not an accident that Orwell’s parable features an immanent malevolent deity– Big Brother ironically fills in for the blind Samael of Gnostic cosmology. The idea that the State could be utterly corrupt is pretty defensible as just an observation on history, but making the State an evil God is absolutely a certain kind of ideology.

But for much of human history, religion and the state were the same, and it’s not like the Church didn’t try.

Deelish…I rally don’t think that’s true. It very much depends on when you think the state formed as an institution, which is arguably post-enlightenment. Even in medieval times, though, the church and the state had a complicated relationship which isn’t well described by saying they were the same thing. And I think that’s generally true for other societies as well (ancient Egypt, ancient Greece, ancient Rome, etc.)

Anyway; I’m with Bert here (as often.) Evil, murderous states are many; omnipotent states are another matter.

I’ll leave aside the application of the definition of statehood to the post-Enlightenment state versus ancient Egypt, Babylon, Rome, etc, except to point out that searching for a bright line between them will bring us to a big distinction in the entwining of religion with those political entities. But by saying the medieval Western Church TRIED, and had ambitions to govern a unified system of earthly power, I’m saying the Church failed – in a way that was good for the dynamism of the Western political tradition, and very different from the level of unification of religious and political power to be seen in contemporary Byzantium, for example. Byzantium as well as those ancient empires entwined religion and politics in a way that can be difficult for the modern mind to grasp; politics and warfare were theological issues. In the ancient world, which god was bigger and had more to do with creating the universe was defined by which power dominated at a given time, and in monotheism it was about whether God was mad at you. While there was a special class of diviners and handlers of radioactive material in the temple, there were also scribes, bureaucrats, military, etc. So, no, the state was never omnipotent, but tried hard to make people think so, claiming its power was eternal and ordained from the beginning of time, the tops of the mountains and the bottom of the sea… and Orwell was talking about the state’s ability to get into people’s heads and warp their reality as powerfully as any religion, no surprise since the communist and fascist regimes of the twentieth century were apocalyptic and millennarian in nature.

Saying that the Christian Church was interested in gaining more power is rather different than saying that the state and religion have been the same thing throughout human history.

Certainly, the state and religion have long been intertwined. And they still are. Were they less entwined or more entwined before nationalism became its own kind of divinity? It depends on your perspective, I guess.

But…the positing of an omnipotent evil god-state is not in itself an act opposed to religion. Quite the opposite.

Noah, are you saying that Orwell positing the evil god-state is religious? I would agree, insofar as the religion is Gnosticism/neopaganism.

I would totally like to know more about Byzantium. Cool mosaics, scary theological disputes.

Yeah, that’s what I’m saying.

“Saying that the Christian Church was interested in gaining more power is rather different than saying that the state and religion have been the same thing throughout human history.”

And I didn’t. I said they were the same for MUCH of human history. The Western Church’s failure to unify Christendom was an important step toward the Enlightenment and modernity.

“Certainly, the state and religion have long been intertwined. And they still are. Were they less entwined or more entwined before nationalism became its own kind of divinity? It depends on your perspective, I guess.”

I don’t see how anyone can look at history and say religion wasn’t more entwined with the state before the Enlightenment and modernity. “Before nationalism became its own divinity” conflates the mystical nationalism of a Hitler with the modern secular state in a way that seems completely unserious to me. The modern secular state is distinguished by a division of religious and political areas and a commitment to religious pluralism that has less in common with Babylonian festivals to Marduk than that kind of religious imperial narrative does with the mystical nationalism of a Hitler, Stalin, or Kim Jong Il (whose successor has already performed several miracles.)

“But…the positing of an omnipotent evil god-state is not in itself an act opposed to religion. Quite the opposite.”

I’m wondering where you’re getting this claim. Orwell wasn’t positing Big Brother as omnipotent- why is life so crummy under Big Brother? Why does it need to alter its citizens’ perceptions of reality?- but threatening that that kind of regime might be victorious in human history. I think you’d be hard pressed to find any religions that associate evil with omnipotence. Associating enemy powers with evil divinities is common, but they’re always on schedule to be routed by the sons of light.

I think insisting that the other guy is the religious nutcase is fairly unserious, actually. Also maybe kind of glib.

I’m well aware of enlightenment modernity’s account of its own victory and virtue. I just wonder if purchasing that line wholesale is necessarily the quintessence of rationalism that it claims to be. When you get rid of god, does god actually disappear, or does man take his place? And does that mean that religion has been banished from power, or that it has been more thoroughly enshrined? I don’t think it’s an adequate answer to that question to point to Byzantium and say that those people were more benighted than we were.

As Bert says, there are gnostic religions which say that the world is irredeemably evil. And Satanism is a religion. So that’s two. I wasn’t particularly hard pressed to find them.

Oh, and I’m not conflating Hitler with the modern secular state. Nazism and Marxism are certainly tinged with religion. But the invisible hand commands its own kind of worship, it seems to me.

I didn’t call anyone a religious nutcase. Whose comments are you reading? I distinguished the modern model of the secular state by its separation of religious and political spheres, and its commitment to religious pluralism. It’s right up there. So…

“When you get rid of god, does god actually disappear, or does man take his place?”

Separating religion from government is not “getting rid of god,” because it creates a separate space for religion. Nobody’s converting churches to temples of reason. There is a vague enshrinement of the country and the ideals of its foundation, but those attitudes are more often conflated with classic religious beliefs than they conflict with them; just not so much as when atheism and heresy were criminal charges.

“And does that mean that religion has been banished from power, or that it has been more thoroughly enshrined?”

Separation of church and state is an attempt to remove religion as a basis for political legitimacy, so, no, while not perfectly successful (show me a viable atheist presidential candidate) it doesn’t mean religion is more thoroughly enshrined. A concept of separate jurisdictions and an invitation to a free marketplace of faiths or lack of faith among the citizenry reduces the political power of religion and the state’s aura of spiritual power.

What are you advocating as a preferable alternative?

“As Bert says, there are gnostic religions which say that the world is irredeemably evil. And Satanism is a religion. So that’s two. I wasn’t particularly hard pressed to find them.”

Gnostics think the world is governed by inferior, evil powers and that their religion liberates them by putting them in touch with higher powers, so they don’t believe in omnipotent evil. As for Satanism, well… I’m not persuaded those people are serious. By definition, can you worship evil? You might think the other guy does. But if YOU think something’s evil, that means you don’t like it.

A stronger candidate for religious belief in omnipotent evil would be misotheism. Unlike an atheist, a misotheist believes in God but hates him. And if H.P. Lovecraft had created a real religion (not quite there yet) that would be a belief in omnipotent, evil gods.

“But the invisible hand commands its own kind of worship, it seems to me.”

The more aggressively religious party in the last election was the one enamored of Ayn Rand, so that sounds right to me too.

There are serious Satanists, yes. There’s a transversal of values, I think. But they explicitly embrace evil. I don’t think evil means “what you don’t like,” in this context. There’s a pretty long history of what evil means which Satanists work with. Transposing values is tricky, I suppose, but if they’re willing to say that worshipping evil is what they’re doing, that seems good enough, to me.

“Separating religion from government is not “getting rid of god,” because it creates a separate space for religion.”

Again, it seems like a matter of perspective to me. The state is saying where and when religion operates. That makes the state in control of religion. The argument is that this reduces religion’s role. It certainly reduces the role of traditional religions like Christianity. Again, I think you can argue that modernity is its own religion, and that it’s more pervasive and powerful than other religions have been — not least because folks basically don’t recognize it as a religion.

Ayn Rand is aggressively atheist. The right’s flirtation with her is in conflict with traditional Christianity — as indeed are such heresies as the prosperity gospel.

And everyone in the US worships the invisible hand, pretty much. It’s too easy to just blame that on the right, I think.

“The state is saying where and when religion operates. That makes the state in control of religion. The argument is that this reduces religion’s role. It certainly reduces the role of traditional religions like Christianity.”

No, the state controls religion and says where it can operate much more when religion is officially combined with government. The modern secular state can still be staffed with religious people and have officials avowedly make decisions based on personal religious convictions, and if anything such claims have the effect of placing themselves beyond argument. A religious sectarian state- and what other kind is there? An ecumenical theocracy?- extends that privilege to only one religious sect.

“Ayn Rand is aggressively atheist. The right’s flirtation with her is in conflict with traditional Christianity — as indeed are such heresies as the prosperity gospel.”

Rand was an atheist, but she’s been adopted by the religious right because these people perceive a war between religion and government in the public sphere and find her catch-all solution of shrinking government appealing. Their idea as I understand it is that if government withdraws from the public sphere the problems it seeks to correct will be solved by a combination of the invisible hand of the market (not at all incompatible with a providential sensibility) and religiously driven charity (although these people confuse their model of Rand+Jesus when they support religiously infused government programs.)

As for being in conflict with traditional Christianity, well, if you’re interested in making money, you might be. But what is traditional Christianity? You just said separation of church and state reduces the role of traditional Christianity; if it’s more defined by having been the state religion of the Roman Empire than its character in Jesus’ time, then you might be right. But separating it from state power could also be argued as returning it to its roots.

“And everyone in the US worships the invisible hand, pretty much. It’s too easy to just blame that on the right, I think.”

From what I see opinion is very neatly divided between right and left in this country with faith in the market to provide solutions on the right and skepticism and desire for more regulation on the left. Most everybody accepts the reality that competition is healthy up to a point. But “worship” means thinking the unfettered market is the best guide to society, and you have to be a real ideologue for that.

Regardless of whether Satanists say they’re worshipping evil, I suspect if you get them talking about their reasons, they get into problems with the definition of evil. If not, I doubt they’re serious. There’s the question of real supernatural belief; for many it’s a symbolic thing. Satanism is hard for me to credit but I guess believing the devil existed might open the door to thinking he was cooler. It’d be a harder sell for atheists.

” But “worship” means thinking the unfettered market is the best guide to society, and you have to be a real ideologue for that.”

I mean, that’s what you say worship is. There are other possible definitions. For example, you might argue that worship is how you shape your life…and capitalism and the market is really central to the way just about everyone in the West functions, whether Ayn Rand devotees or academic Marxists. Folks may talk about tinkering at the margins, but their basic commitments are what they are.

I think we’re talking past each other in a lot of this. If you’re interested in where I’m coming from, I sort of work some of this out more fully in a slightly different context here.