I’ve been reading Jason Mittel’s book “Genre and Television” over Christmas break. In many ways, his take on genre is similar to John Rieder’s. That is, Mittell argues, like Rieder, that genres are constituted not by formal traits, but rather by social or cultural agreements or discourses. So (for example) it might make sense to call something a “comic” even if it were entirely text with no pictures, if the text was written by Dave Sim and came in a floppy format and was sold through a comics store and was part of an ongoing series that people thought of as a comic. Along those lines, a while back I defined comics as those things which are accepted as comics.

I still stand by that definition…but Mittell puts some interesting twists on it. Specifically, when I talk about what things are accepted as comics, I tend to think of the accepting as being done by folks in the comics world, who care about comics. That is, comics is defined by what comics folks (whoever they may be) think of as comics. That can be scholars, fans, readers, or whatever. But to participate in the process of definition, I was assuming, you need to want to be participating in the process of definition. People who don’t care about comics don’t care about comics — someone who has never read or seen a comic is not the person you want to go to for a definition.

Mittell isn’t so sure. For him, television genres are constructed socially, by everyone — even, and sometimes especially, by people who are not fans, or scholars, or even by people who have never watched or thought about the genre in question. Instead, genres are often shaped, or defined, by institutional forces or regulators…or even just by people who have heard something about a show and formed uninformed opinions about it. Thus, early television quiz shows were strongly shaped by federal regulations against lotteries. Even though the Supreme Court eventually determined that game show giveaways were not in fact lotteries, the federal scrutiny of the shows had a strong effect on which shows were made and how, and on public perceptions of the genre, which long had a whiff of scandal and illegitimacy associated with it — perhaps handed down to its progeny, the reality show. (The parallel here with the comics code is fairly obvious.)

As another example, Mittell argues that the genre of talk shows, and especially of daytime talk shows, was importantly shaped and understood through the opinions and ideas of people who did not watch those shows. That is, discussion of the genre — which is in many ways the genre itself — was based on an image of those shows as lowbrow, white trash fare for morons. That’s the vision of those shows that largely circulated as a genre marker in public perception.

Comics, then, is neither constituted by formal elements nor by fan or expert practices or discourses. Rather, it is constituted at least in part by those who do not necessarily read comics at all. And if that’s true, it’s possible that comics are, in fact, in many ways a genre — rather than a medium, which is what most fans and scholars and people who care about comics prefer to think of them as.

Certainly, in the world outside comics-centric blogs, I think there’s little doubt that comics tend to be treated as a genre. For instance, at Netgalley, where book critics can see previews of forthcoming books, comics is one option among many genres, listed as a search option alongside “mystery” or “nonfiction” or “science-fiction”, or what have you. On Amazon, too, there is no separate category for comics; they’re simply subsumed in books, rather than being broken out into their own larger block like movies or music.

Of course, the distinctions between genre and medium is fairly arbitrary anyway. There’s no real formal or ideological reason to think of television as its own medium, for example — it could just as easily be thought of as a genre of film, or both film and television could be thought of as subgenres of “screens,” or even of theater.

Still, the cultural subdivisions are what they are, and the fact is that film, and theater, and even television, are all much more firmly established — institutionally and culturally — as mediums than comics are — a fact which becomes especially clear if you start looking at places and people who maybe don’t care about comics that much to begin with.

So what does it matter if comics are a genre rather than a medium? To some degree, it probably doesn’t matter at all; a comic by any other name will smell as sweet, or as putrid, as the case may be. But, on the other hand, it seems like seeing comics as genre could in some cases shift the context in which comics are discussed, or point towards different questions.

For instance, Mittell talks about the Simpsons as a genre mash-up, in which the genre suppositions of sit-coms, and the genre suppositions of cartoons, are used to undermine or question each other. The formal potential and expectations of cartoons made it possible to create a sit-com with more characters and more venues; the genre expectations of sit-coms made it possible to see a cartoon as aimed at adults (and programmed outside of Saturday morning.)

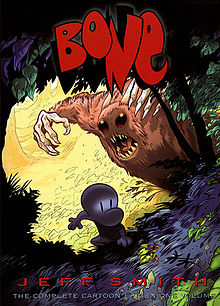

Many comics could be talked about along similar lines. For example, Maus might be seen as a mash-up of memoir and comics, using tropes of each to create a crossover audience that appeals to a greater number of people than either memoir or comic might have been able to attain on its own. Bone could be seen as mixing comics genre and fantasy genre in a similar way — and/or to tweak the conventions of both. And/or, a television show like Heroes might be seen as combining comics genres with serial evening soap opera.

Many comics could be talked about along similar lines. For example, Maus might be seen as a mash-up of memoir and comics, using tropes of each to create a crossover audience that appeals to a greater number of people than either memoir or comic might have been able to attain on its own. Bone could be seen as mixing comics genre and fantasy genre in a similar way — and/or to tweak the conventions of both. And/or, a television show like Heroes might be seen as combining comics genres with serial evening soap opera.

None of these ideas are necessarily innovative or undiscussed or anything. But I think they might be inflected differently, and perhaps more central, if there were less concern with comics’ medium specificity, and more willingness to think of comics as one genre among many. In particular, there might be less focus on comics’ definitional project, and more focus on how comics has functioned, or been thought of, or been used at specific moments or in specific situations.

Seeing comics as genre might also help to explain, or help in a discussion of, the way that comics often seems to function in popular discourse as a kind of novelty. The “Bang! Biff! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore!” meme might be seen not so much as an insult to the comics medium, but rather as what the comics genre is most often perceived as offering the mainstream. Just as the Simpsons cartoon form, with its connotations of flexibility and childish freshness, helped reinvigorate the sit-com, so comics’ associations with wild fantasy and childishness may be precisely why people are so interested in a comic book Holocaust memoir, or a comic book fantasy epic, or a comic book piece of journalism, or what have you. Instead of “how is the medium of comics defined?” the question might be, “what pleasures or interest does the comics genre offer?” Rather than trying to figure out how to separate comics from everything else, it might be more useful to look at the many ways in which comics shamelessly and continuously hybridizes.

The biggest issue with defining comics as a medium is the question of “which medium?” Up until a few decades ago, this wasn’t an issue – comics were printed on paper and that was the end of it. Now we have comics on the screen, which is a perfectly valid medium – webcomics have the word comics right there in the name. I’d say that comics are medium-dependent – they need a medium in order to exist. And yes, I am deliberately conflating the two uses of the word medium; I think the similarity of connotations between the two meanings are relevant to the discussion.

That said, I’m not sure that comics constitute it’s own genre, exactly – that statement implies inherent limitations. Coming from the English-speaking comics market, it’s easy to see why the mainstream audience sees comics as a single, monolithic genre – a single genre does dominate the market and, thus, the perception of comics. But that situation is not global in scope.

It’s almost like there should be a third category, halfway between medium and genre – some kind of metacategory that would allow for discussion of presentation and content without muddying the waters with medium or genre considerations or implications, each of which has it’s own built-in limitations.

Your comment on quiz shows being shaped by regulation is strongly reminiscent of a similar case.

In early 19th century Britain, theatres had to be licensed, and these licenses were doled out sparingly– I think just 3 for London. Operas and concerts, though, were, not regulated.

So some smart impresarios took popular plays, added continual musical accompaniment with the odd song and/or dance number, and a new genre was born: the melodrama.

RM, I think the comparison with cartoons is maybe useful. Cartooning functions as a genre within television, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that cartooning can’t exist outside television (as film shorts, as web cartoons, as film features, etc.)

I was actually thinking about your point that television and movies are connected because they share the same kinds of visual presentational aspects, but are differentiated for a variety of reasons – they belong to a common category that isn’t quite a medium and certainly isn’t a genre.

Okay…I think the point for me is that none of these categories are natural or formal? That is, television and film *could* belong to a common category, but they kind of don’t just because they’re not usually thought of that way….

I actually think that the fact that they don’t belong to a common category specifically because nobody thinks of them as a common category is what’s interesting about the conversation. The only real differences between TV and movies are relative production values based on release schedules – one is episodic in nature and the other isn’t. Except that some movies have sequels and some TV shows are starting to display much higher production values.

To bring it back to comics, I think of graphic novels as the movie analog and so-called floppies as the TV analog. There is no question that both are comics, but do the format and release schedule provide the definition or does the public perception provide the definition?

If the TV/movie divide is correct AND the lack of a real conceptual divide between graphic novels and floppies is also correct (and there is really no reason they can’t both be right), then the genre definition you propose above is really built on historical accidents, not a real formal structure. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing, it’s just an interesting way of looking at the whole mess.

I think comics are a genre that happens to appear most often in one medium, but sometimes occurs in other media.

I’d argue that Batman the TV show was a comic on TV. (Did you ever see Strictly Ballroom? Although it was a dance movie, it had a very live musical theater type feel, even to the story.) Same with some of the comic movies–the color schemes, the weird outfits. And then there’s that Bruce Willis and whatshername alien-scifi movie that looks just like a comic, but isn’t one.

I think that’s certainly a reasonable way to approach it. One of the things that thinking about comics as a genre rather than a medium does is it makes it easier, or more natural, to see comics as tropes which can be picked up and used in various places. So…I don’t know that I’d say the Batman TV show was a comic, precisely, but obviously it was taking tropes from comics, or using bits of the comics genre in important ways.

Many, many people have said that the Batman show was like a comic book on tv. But an important word in that sentence is like. Having points of resemblance is not the same as sharing an identity.

I think you’re approaching this the wrong way.

What the TV/cinema divide suggests is that the media themselves are constructed through a consensus between diverging discourses, while we tend to think of them as a mere catalog of formats. Media are problematic, and comics especially so.

This is something media have in common with genres, which are also the product of a consensus between a variety of social bodies (critics, producers, distributors, librarians, the uninterested-public-at-large, etc.). Still, the fact that genre and media are both social constructs, the product of a form of negociation does not make them interchangeable. It seems to me that to treat comics as a genre is to deprive ourselves of a usable distinction.

I’d agree that media are constructed as well. My point was that comics aren’t necessarily constructed as a medium — that is, it’s not entirely clear whether they’re one or the other. That means that you can see them as either…and this post is suggesting some of the ways in which seeing them as a genre might be useful or interesting in certain respects.

I agree 1000% with Nicolas. The facts that

(1) the divisions between genres are socially constructed

(2) the divisions between media are socially constructed

do not entail that

(3) (we should consider)(it would be useful to consider)(whatever) the category of “comics” as a genre rather than a medium,

any more than these facts

(1′) the divisions between “mental illnesses” are socially constructed, and

(2′) the divisions between “races” are socially constructed

entails that

(3′) we should consider the category of “caucasian” as a mental illness.

Similarly, the fact that

(5) some (many?) businesses treat “comics” as a category analogous to uncontroversially generic categories (like “non-fiction” or “sci-fi”)

does not entail (3). It is possible to believe the conjunction of (1),(2) and (5) without believing (3); this is because (1),(2) and (5) are true and (3) is false.

Oh, all right, less trollishly: it’s because (1),(2) and (5) are obviously true and (3) is at the very least dubious. This sentence “And if that’s true, it’s possible that comics are, in fact, in many ways a genre”, on which the post hinges, is a massive non sequitur. (1),(2) and (5) have nothing to do with (3).

Jones, your logician’s take is always fun. But I don’t think you’re working this through very clearly.

In the first place, you need more than an assertion to explain why people treating comics as a genre doesn’t matter. If genre is a social construct, and there is a fair bit of evidence that people treat comics as a genre, then comics is, or can be considered a genre. Amazon is a big fucking deal, it seems to me; if they essentially treat comics as a genre, that seems fairly important.

Second, I give a bunch of reasons and examples as to why treating comics as a genre might lead interesting places. Your account of the logic of the post is simply wrong. My argument is that seeing comics as a genre makes it easier to think about them in relationship to other genres, rather than focusing on a definitional project in the name of exclusivity. If you disagree, disagree with that. But I never said that the fact that you can see comics as a genre means that it will be interesting to think of comics as a genre. There’s a bunch of stuff in the middle there that you skipped over.

Just to be clear; obviously, it makes sense in a lot of ways to think of comics as a medium too. But comics studies/scholars pretty much *always* starts from the presupposition that comics is a medium. That’s why the definitional project has been so important. I think you might end up more interesting places, or at least alternate places, if you thought about the ways comics might be a genre. And I think that there’s plenty of evidence from the culture (not least the fact that comics folks jump when you say comics is a genre) to suggest that comics is at least in some circumstances thought of as a genre, not a medium.

————————-

RM Rhodes says:

I actually think that the fact that they don’t belong to a common category specifically because nobody thinks of them as a common category is what’s interesting about the conversation.

———————–

Yes. Does that mean that, in the antebellum South, blacks did not belong to the common category of “human beings” — which encompassed the British, French, etc. — because (virtually) nobody thought of them as such?

We’re in the “reality is created by what we think about it” territory.

————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…when I talk about what things are accepted as comics, I tend to think of the accepting as being done by folks in the comics world, who care about comics. That is, comics is defined by what comics folks (whoever they may be) think of as comics. That can be scholars, fans, readers, or whatever. But to participate in the process of definition, I was assuming, you need to want to be participating in the process of definition. People who don’t care about comics don’t care about comics — someone who has never read or seen a comic is not the person you want to go to for a definition.

————————-

Ay, there’s the rub! If comics are “comics as those things which are accepted as comics,” what if the overwhelming majority consensus is that comics are kiddie crap, mostly superhero fare?

If you have a formal definition delineating the parameters of what constitutes an art form, you can at least say (as Scott McCloud, in effect, did) that even if what is produced in the artform is mostly crap, comics do not have to be that way; crappiness (simpleminded, violence-laden adolescent power fantasies) is not essential to comics.

———————–

vommarlowe says:

…I’d argue that Batman the TV show was a comic on TV. (Did you ever see Strictly Ballroom? Although it was a dance movie, it had a very live musical theater type feel, even to the story.)

———————-

My wife was very into dancing; I’m of the two-left-feet variety, but we both love “Strictly Ballroom.” And yes, come to think of it, there is “a very live musical theater type feel” to it.

But I’d say that the Adam West “Batman” was a TV show that employed cornball superhero comics tropes and stylistic approaches.

It’s not a series of static images juxtaposed in order to create an aesthetic/narrative effect; therefore, not a comic.

———————–

Tom Crippen says:

Many, many people have said that the Batman show was like a comic book on tv. But an important word in that sentence is like. Having points of resemblance is not the same as sharing an identity.

————————

Indeed so!

————————-

Nicolas Labarre says:

What the TV/cinema divide suggests is that the media themselves are constructed through a consensus between diverging discourses,

————————–

Mmmmnnnnoooo. throughout the vast majority of TV and movies’ histories, television was something seen in people’s homes through a receptive device that picked up broadcast signals. For movies — aside from those who had a Super 8 camera and projector combo — you went out of your home to see images on a strip of film projected on a screen, in a public setting.

Why do I have the feeling that those who originally came up with malarkey ideas like “the media themselves are constructed through a consensus between diverging discourses” are ivory-tower academics who couldn’t put together a rudimentary hammer if their lives depended on it, so abstracted from physical reality as they are?

To be continued; same Bat-time, same Bat-station!

I actually teach graphic literature as a genre of literature that allows the instructor and the reader to better assimilate the language and symbology inside the graphic text into usable, spoken, and written English. I’ve had “discussions” with colleagues for over a decade about this approach as being “non-academic” and a waste of time and resources. How odd I find it that the students, especially ESL students, who utilize my method actually learn the language faster and with better coherence in usage than those who grew up speaking English.

Huh; that’s interesting. My son I think used comics to learn to read in a lot of ways….

I think one advantage of thinking of comics as a genre might be that it could be assimilated into literature in some ways for some purposes. I hadn’t thought about it in the context of teaching reading, but it makes sense….

Mike – that’s a false equivalency and you know it. The definition of human being is anatomically-based. I know where you’re going, but I think it’s fair to say that when you are talking about art, “reality is created by what we think about it” is not necessarily a bad thing. We’re discussing how to properly classify stuff that has been created – made tangible – by someone. It’s space-cakey, sure, but so is the creation of art. But it’s certainly not slavery.

One of the problems with the “comics is a genre because the culture says so” model is that it doesn’t look at all comic book cultures for validation. Does France or Japan consider comics to be a genre? Actually, no. The French (or, at least, the literary magazine Marianne did in their Angouleme 2010 issue) identify the following distinct genres in BD: Heros, Adventure, Detective Novels, Heroic Fantasy, Drama, Humor, Historical, Biography, Science Fiction, Reporting, Social Critique, Adaptation and Erotic. I’m fairly sure that Manga has an equivalent number of genres associated with it in the Japanese market.

In defining comics as a genre, either the Anglo-American market & culture is really far ahead of the other two major comics cultures or it’s regrettably far behind. Again, I think it’s interesting that our culture has come up with this solution for an artform that doesn’t really fit in anywhere else, but if it is a cultural construct, it’s probably important to ask why it was constructed in this shape. And if it’s necessarily a good thing.

A genre can have genres or sub-genres within it. Happens all the time.

Still, I’d agree that comics looks more like a medium in France or Japan than it does in the US.

Hi Noah,

Your ideas have a certain appeal, but I still cannot see what this definitional change from medium to genre accomplishes, except perhaps exchanging one set of arguments one set of questions (must comics contain sequential images, have words and pictures, etc.?) with a second set (must comics have have generic markers X, Y, Z?). And I’m not certain why the latter queries are more fruitful than the former. I am all for disposing of questions that have outlived their usefulness, but what is the utility of your new tool?

I would try to be more specific, but that lack of specificity also part of my confusion with your post (as indicated by my “X, Y, Z” placeholders, above). What exactly the markers, for you, of comics tout court as a genre?

In your essay you suggest three qualities, two of which are actually about, I guess, animated cartoons: “flexibility and childhood freshness.” Are these generic qualities for comics? If so, what aspects of the genre of comics are we describing? Their association with a cartoony style? With comedy (hence “comics”)? With stories designed for little kids?

Your last generic marker — the only one you link to comics themselves, albeit implicitly — is (“Biff! Pow!”) superheroes. And this may still be an accurate connotation for the term “comic books” for many people (although not, perhaps, for “graphic novels”).

But even if this is an empirically true statement — true, that is, that most people think of superheroes when they think of comics. But is it enough to define comics as a genre? And why can’t that genre simply be “superhero stories”?

More to the point, what does this new generic definition get us that we weren’t already doing? We can look around and decide “what most people talk about when they talk about comics,” but that seems simply to reproduce the types of questions that, say, cultural-studies or audience-response or genre-studies critics are already asking?

* * * * *

I could probably push this farther, in ways that other readers have already tried. What, for example, happens if we find out that most people “recognize” comics not by its generic qualities (it has superheroes, cartooniness) but by its medium-specific characteristics (it has arrangements of pictures in boxes that tell stories).

Here’s a thought experiment. Line up (a) a broadcast of the Batman TV show, (b) a projection of a Batman movie, (c) a recording of the Batman radio show, (d) a costumed kid acting like Batman, (e) a novelization of a Batman story, and (f) a copy of Batman #1. Ask 100 people which one is the comic. How many would have any trouble understanding the question? How many would identify the printed matter with panels and pictures (f) as “the comic”?

Now run the same experiment again, and this time ask, “Which of these is the superhero story”? I expect a lot more confusion the second time around — and a wider variety of answers, if answers is forced. Some respondents might even have to *read* (or view) the *contents* of the stories before deciding.

* * * * *

But all this may still be beside the point, at least until I understand better what you mean when you talk about the genre of comics.

My best

Peter

I also think that most people think “newspaper comics” instead of “superhero comics” when they think about comics. Many don’t even know that the Spider-Man character they watched on the movie screen is a comics character.

My apologies for the typos. If I wrote less, I might proofread more.

Domingos, that’s a good point. Without surveys, etc., it’s hard to figure out what people do and don’t know (though you can look at things like Amazon for institutional markers.)

Peter, I guess the issue for me is that I feel like a lot of energy in comics studies goes into, or has gone into, making comics the equal of literature or film or what have you — presenting it as a medium worthy of study.

Mittel’s approach seems to raise less of those issues, or put them aside. He’s not worried about whether, say, cartoons are an aesthetic object worthy of study — instead he’s interested in how the genre of cartoons has been used in specific times, or (often) how it’s hybridized with other genres in particular cases.

Again, I’m not saying that people don’t do that kind of work with comics. But to me it feels like the definitional questions, and the arguments over medium specificity, are more central questions, or ones that are pushed more. Turning to comics as genre seems like a way to try to get out of what becomes a more or less constant, repetitive enactment of status anxiety.

In terms of your question…I bet there would be a not insubstantial number of people who wouldn’t know what you meant by “a copy of Batman #1.”

On the other hand, if you asked people what a comic is, I bet you’d get a lot of answers that steered towards genre (talking about supeheroes, or that it’s for children, or what have you) rather than formalist arguments.

Not that I’m against formalist discussions at all — I actually really like thinking about comics form in various ways (and a fair bit of my writing is oriented that way.) But…I do think at this point speculating or thinking about how people might think about comics (for instance, about how comics tropes were used in the Batman TV show) seems more fruitful than trying to nail down what a comic is in a formal sense.

“I bet there would be a not insubstantial number of people who wouldn’t know what you meant by “a copy of Batman #1.”

Not if they were looking at it, which is the test he proposes. They would say, “That’s a comic book.”

———————-

RM Rhodes says:

Mike – that’s a false equivalency and you know it. The definition of human being is anatomically-based.

———————-

And the differentiation of “television” versus “movies” I gave was physically-based (which includes the varieties of Homo Sapiens):

“…throughout the vast majority of TV and movies’ histories, television was something seen in people’s homes through a receptive device that picked up broadcast signals. For movies — aside from those who had a Super 8 camera and projector combo — you went out of your home to see images on a strip of film projected on a screen, in a public setting.”

In other words, these are all arrangements of matter that, among others of the same groups (humans, TV sets), share certain parameters, operate in similar fashion.

If you seriously validate more “fuzzy,” public-opinion “what we think about it” factors as determining what something/one is, though in some ways it might “not necessarily [be] a bad thing,” it opens an industrial-size barrel of worms.

————————

We’re discussing how to properly classify stuff that has been created – made tangible – by someone. It’s space-cakey, sure, but so is the creation of art. But it’s certainly not slavery.

————————

What, newborns just spontaneously generate, like flies were thought to be magically created as a side-effect of meat rotting? Somehow, I’ve got the impression that babies were ” created – made tangible – by someone”…the parents.

Where I brought slavery in, is as the ultimate example of where letting mutable, historically- and culturally-variable popular consensus — rather than plain physical factors — determine what anything or anyone is.

—————————

…In defining comics as a genre, either the Anglo-American market & culture is really far ahead of the other two major comics cultures or it’s regrettably far behind. Again, I think it’s interesting that our culture has come up with this solution for an artform that doesn’t really fit in anywhere else…

—————————–

Excellent points! Though rather than “our culture” having this belief, it’s a microscopic minority, Academic Theory-speak types who are holding it forth.

Felt like a shot of William Gibson in my reading; checked out his “All Tomorrow’s Parties” from the library, and in one page this morning read:

“The sharehouse was full of USC media studies students, and they got on her nerves. They sat around accessing media all day and talking about it, and nothing ever seemed to get done.”

——————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

A genre can have genres or sub-genres within it. Happens all the time.

——————————–

Sure. So?

———————————

Still, I’d agree that comics looks more like a medium in France or Japan than it does in the US.

———————————-

Looks more like? Does the Earth “look more like” 10,000 years old in some podunk town in Mississippi, 4-1/2 billion years old in Cambridge?

So, is a copy of “Blazing Combat” in Tokyo part of the comics medium, but if teleported to Boston, transmogrified into part of the comics genre?

———————————-

peter sattler says:

Here’s a thought experiment. Line up (a) a broadcast of the Batman TV show, (b) a projection of a Batman movie, (c) a recording of the Batman radio show, (d) a costumed kid acting like Batman, (e) a novelization of a Batman story, and (f) a copy of Batman #1. Ask 100 people which one is the comic. How many would have any trouble understanding the question? How many would identify the printed matter with panels and pictures (f) as “the comic”?

————————————

Heh, heh! Bravo!

Tom, I guess so…but most people could identify a cartoon as a cartoon, at least in most cases. But Mittel still argues (with some justice) that cartoons can be treated as a genre.

It’s worth remembering that Scott McCloud wouldn’t identiy Dennis the Menace as a comic. On the other hand, most people, if asked whether (a) the batman tv show, or (b) an abstract comic were a comic, would quite possibly choose a. Similarly, if you showed people Maus and asked if it were a comic, you’d probably get a lot of, “well, maybe, but…” And I don’t know what you’d get if you showed people a Mo Willems children’s book; probably confusion again, in many cases.

Mike – I find it very amusing that you equate an artform like comics with an institution like slavery and, in the same breath, poo-poo academics who take media studies too seriously. Which is it? Is comics at the same level as the enslavement of human beings or is it an artform that is taken far too seriously by ivory-tower academic types?

I understand that you’re coming at the argument from a formalist point of view and, to a certain extent, I agree that there should be some kind of definition beyond being able to say “I know it when I see it.” However, there is a certain amount of fuzziness around the definition of comics – is the Bayeux Tapestry comics? What about Lynd Ward’s Wild Pilgrimage? Or Les Portes du Possible? Or Signal to Noise? Or Castle by David Macauley? At a certain point, the formalist definition has to cave to consensus because there’s always one more exception floating around.

Meanwhile, most artists I know don’t really seem to care what is or is not considered to be comics and just pick and choose their inspirations as they see fit. I doubt that Darwyn Cooke really cares if Edward Tufte’s work is considered to be comics, but he included a really interesting infographic in his adaptation of The Outfit, which explained a part of the story quite nicely.

There’s lots of different ways of thinking about groupings of art. I’d say that to the general public, the capes and the characters are more important than the media–they’ll say Batman is a comic regardless of whether it’s a floppy, a graphic novel, a TV show, or a movie.

Which is, I think, an interesting way of getting at the stories that mainstream comics like to tell. Bam! Pow! Maybe those action words are important. Or maybe the duality of natures (reporter vs supe, businessman vs vigilante), or maybe the folk-tale like plots. I don’t know, but it’s just interesting.

Another way to approach it would be to say, a novel is a longform story written by an individual and presented as a single unit. That’s why Maus is a novel (at Powells, we shelved it in lit). Comics are short to longform stories presented in installments that are created by committees of people under corporate guidance, and thus are much more like TV.

I’m sure a whole bunch of people are going to now scream at me, but the thing is, I’ve got some experience in crafting stories alone, and crafting stories in collaboration with another person, and crafting them as a group, and it’s really not at all the same, nor does it result in the same kind of story (IMO).

Yes, yes, plenty of American smallish lit-type indie comics are done with a single comic artist, but *most* of them are done by committees. Individually run TV shows exist (for all intents and purposes) on YouTube, so Jeff Brown would fit in there, if we were comparing, whereas a tapestry would actually be more like a comic because of the group creation.

There are big differences in the skill sets required to make movies or stage shows, blog posts or novels, New Yorker cartoons or daily strips, comic books or graphic novels. And then, there’s a difference between what is involved in writing a script that could be realized as either a tv show or a comic, and the range of abilities that would be involved in actually drawing that comic form that script. The reader can sit and absorb that story in the format of a tv show or a comic with a similarly low degree of effort and attention and consider both to be the same thing, but that don’t make it so. I was under the impression that genre indicated a type or category of storytelling entertainment, be it horror, crime, romance, war, etc, not to be confused with a specific method or means of storytelling: prose, theatre, film, comics.

———————

RM Rhodes says:

Mike – I find it very amusing that you equate an artform like comics with an institution like slavery…

———————

…And I find it gigantically amusing that people can’t tell the difference between human beings and “institutions.” I guess that’s what all that Academese does to the brain…

The earlier exchange:

————————-

RM Rhodes says:

I actually think that the fact that they don’t belong to a common category specifically because nobody thinks of them as a common category is what’s interesting about the conversation.

———————–

—————–

(Yours truly says)

Yes. Does that mean that, in the antebellum South, blacks did not belong to the common category of “human beings” — which encompassed the British, French, etc. — because (virtually) nobody thought of them as such?

We’re in the “reality is created by what we think about it” territory.

—————

In other words — let’s see if I can simplify this enough to get the point across, though I’m not counting on it — if we accede to an attitude where the “popular consensus” is seriously considered worthy to decide that “A” is actually “B,” that lays the groundwork for attitudes such as “blacks are not human beings.” And lays the groundwork for making the institution of slavery morally acceptable; don’t we make animals do “involuntary servitude,” after all?

To pick away some more, from a different angle:

————————–

RM Rhodes says:

Mike – I find it very amusing that you equate an artform like comics with an institution like slavery and, in the same breath, poo-poo academics who take media studies too seriously. Which is it? Is comics at the same level as the enslavement of human beings or is it an artform that is taken far too seriously by ivory-tower academic types?

—————————

This is like a Fox News “reporter” saying to someone voicing opposition to the war in Iraq, “Which is it? Do you liberals just hate America, or do you want the terrorists to win?”

I neither “equate an artform like comics with an institution like slavery,” nor “poo-poo academics who take media studies too seriously.” Certainly many academics deserve huge amounts of razzing, but it’s for idiotic theories and muddled thinking, not for being “too serious.”

————————–

…However, there is a certain amount of fuzziness around the definition of comics – is the Bayeux Tapestry comics? What about Lynd Ward’s Wild Pilgrimage? Or Les Portes du Possible? Or Signal to Noise? Or Castle by David Macauley?

—————————

Yes, there are areas where the boundaries grow blurred. Getting “anatomical,” is a fetus, or someone whose brain has been destroyed and is kept alive by respirators, or a mutated person (say, an androgyne), or — if such a thing could exist — a person’s intelligence and personality, cut off from the flesh…

…a human being?

However, that doesn’t mean that…

————————–

At a certain point, the formalist definition has to cave to consensus because there’s always one more exception floating around.

————————–

…which is a similar argument to what Creationists use; because science can’t dot every “i” or cross every “t” of physical reality, therefore it’s all a matter of faith, it’s all subjective.

Why do the knowledgeable have “to cave to consensus,’ because there are a few oddities that don’t quite fit?

Especially when that consensus is not specifically limited to the cognoscenti, but as repeated examples in this discussion make clear, includes every doofus, ignoramus, and jackass out there; people for whom it was indeed a shocking revelation to learn that “Bang! Pow! Comics aren’t just for kids anymore!”

I’ll certainly agree with Noah that “someone who has never read or seen a comic is not the person you want to go to for a definition,” and extend that to those whose knowledge of comics is grossly limited.

As Sam Goldwyn allegedly put it, we should “include them out” of the consensus.

—————————-

vommarlowe says:

Another way to approach it would be to say, a novel is a longform story written by an individual and presented as a single unit. That’s why Maus is a novel (at Powells, we shelved it in lit).

—————————-

And when other bookstores shelve “Maus” cheek-by-jowl with the “Spawn” collections (as I’ve seen them do), does it then change into a comic book?

—————————-

…the thing is, I’ve got some experience in crafting stories alone, and crafting stories in collaboration with another person, and crafting them as a group, and it’s really not at all the same, nor does it result in the same kind of story (IMO).

—————————-

But aren’t they all…stories?

If an author has a tale in mind, and types it out “straight,” or under the influence of hallucinogens, it would alter the “flavor” and approach, but it would still be a story.

—————————–

…whereas a tapestry would actually be more like a comic because of the group creation.

——————————

And, an automobile would actually be more like a comic because of the group creation.

“We’re not in Kansas any more, Toto!”

I didn’t wade through all that, but let me explain a bit more what I meant.

One striking feature of modern mainstream comics, as a genre, is the bizarre (to me) crossover fetish. Practically anytime I tried to pick up a floppy, it was a crossover. You could say, Hey, comic readers looooooooooove crossovers! Or you could say, hey comic writers/artists/inkers/colorists adore crossovers.

Or you could look at the way the mainstream comics are created by two distinct corporations, and go, Cui Bono. Well, Marvel, that’s who. Where else have I seen crossovers? TV. Why? To boost ratings. I’m not saying that’s bad, but if corporate financial needs play a part in the way that stories are told or what sort of stories get told, then that will impact comics as a genre.

I would say that one of the other aspects of modern mainstream comics is a–how can I put it. A somewhat flattened id. In novels, indie comics, and even manga, you get some wild id stuff. Like classic Wonder Woman. You get bondage and Space Kangas and jousting.

A work created by committee is going to have more aspects of the weird shit tossed out by sheer social pressure. “And then the space kanga lands on the–” “Man, are you nuts? Quit it with the marsupials!” “Awww, I like marsupials.” “Well, give it a rest for the next six issues.”

On the other hand, with a large body of artists sharing a work, it’s possible to keep creating a work long past the exit of a single creator and yet still, to the reader/viewer/etc it remains the work. You can see this in practically all the mainstream comics characters, but also in other medium/genre combos, such as Soap Operas on TV. Maybe the group creator model allows for truly longform short-issue artistic works. Or maybe it’s the group creator model that imbues so many of them with melodrama. I don’t know. But it seems worth considering.

And yes, I’ve seen some people argue that Maus is a comic. Others that it is a novel. Neither need be right or wrong, both can co-exist, but I think it’s valuable to ask why one views it one way, another the other.

———————-

vommarlowe says:

…And yes, I’ve seen some people argue that Maus is a comic. Others that it is a novel. Neither need be right or wrong, both can co-exist, but I think it’s valuable to ask why one views it one way, another the other.

———————–

Can’t help but be reminded of the old “Certs is a breath mint!” “No, Certs is a candy mint!” controversy. (For the youngsters, this classic: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=E8zwnXjIjPM )

As to why an individual may “prioritize” a particular definition or aspects of a work, surely it’s due to those factors they personally value most highly or consider most salient / important.

In most bookstores and libraries, I’ve seen graphic novels / comics collections in their own category. However, annoyingly, libraries in town do not separate genre novels — mysteries, SF — into their own category.

For those who enjoy a particular genre, no longer can you look through the collected offerings in one spot; you must search for specific authors, or the little library genre icons glued to the spine. Which is most unhelpful.

(Come to think of it, though, the Main Library has a section of paperbacks which are divided by genre…)

As to “Maus,” is it simply a plain ol’ novel?

—————-

1. A fictional PROSE narrative of considerable length, typically having a plot that is unfolded by the actions, speech, and thoughts of the characters.

—————-

1. (Literary & Literary Critical Terms) an extended work in PROSE, either fictitious or partly so, dealing with character, action, thought, etc., esp in the form of a story

—————-

1. an extended fictional work in PROSE; usually in the form of a story

——————

emphasis added; from http://www.thefreedictionary.com/novel

…Spiegelman’s book may have, as most GNs do, some “novel-like” characteristics (“a fictional or partly so narrative”; in that book’s case, certainly the cat and mouse conceit is “fictionalizing”). But, for that matter, so do most TV shows and movies, epic poetry, tales of folklore.

———————

Definition of GRAPHIC NOVEL:

a fictional story that is presented in comic-strip format and published as a book

———————

http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/graphic%20novel

———————-

A novel whose narrative is related through a combination of text and art, often in comic-strip form.

———————–

a novel in the form of a comic strip

———————-

http://www.thefreedictionary.com/graphic+novel

Well, we “comicscenti” might argue with “comic strip”; I think of it as something like “Dick Tracy” or “Dilbert,” published in mostly tiny daily story-spurts, rather than a sustained narrative.

However, the mainstream “consensus” is that “comic strip” is…

———————–

1. A usually humorous narrative sequence of cartoon panels: taped a comic strip to her office door.

————————

a sequence of drawings telling a story in a newspaper or comic book

————————

Eeesh! So is a Jack Kirby page from a “Fantastic Four” comic then to be considered a “comic strip”?

But the French might call a “comic strip” a serialized multi-page bit of story, to be later collected in an “album”:

————————

bande dessinée – comic strip

bande dessinée de presse – cartoons in the press

album de bande dessinée – comic book

————————

http://dictionary.reverso.net/french-english/bande%20dessin%C3%A9e

———————–

Franco-Belgian comics…are known as BDs, an abbreviation of bandes dessinées (literally drawn strips) in French and stripverhalen (literally strip stories) in Dutch.

————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franco-Belgian_comics

My interest in this issue comes from giving a talk to some art students a while back about cartooning and having them resist my request that they take cartooning seriously, which they expressed by asking me “but isn’t cartooning a ‘cool’ medium”? Not having read much McLuhan, I was a little flummoxed by the question, but it did occur to me that it makes a big difference through what physical medium you experience cartooning, and that cartoons/comics in ink-on-paper have always felt particularly hot to me, if by “hot” you mean engaging and demanding and motivating. Cartoons/comics on TV by contrast seem to me to engender irony and detachment. You could even argue (I’m not sure I would) that the Simpsons show is acceptable to the Fox network despite its radical politics because the show leaves you feeling superior and complacent, not angry and motivated.

My two cents: I would be curious to hear how those who argue that comics are “a method or a means of storytelling” (I am quoting James) would answer the question: yes, but how is this method defined? Because then you are back to the well-known uncertainties, aren’t you? If you say: A series of images in sequence that tell a story – Well, do you really want to exclude all of the single-panel cartoonists? I think that the relevance of other criteria of definition besides the formalist one, or the “medium-theory”, must seriously be considered. One might say “genre”, but one might also say “iconography”. A lot of single-panel cartoons and animated cartoons share a common iconography with a lot of comics, which kind of links them. If I think of this connected galaxy of similar images in different “media”, it does not seem far-fetched to me to call this the “genre” of comics, and this genre has actually nothing to do with it being in single images or sequences, printed on paper or flickering on a screen, moving or still, or whatever.

I’ve no trouble with seriously considering “the relevance of other criteria of definition besides the formalist one.”

Even if they don’t precisely fit, or may not wholly qualify as “comics,” they can certainly serve as food for thought, inspire creative approaches other than the “classical” one.

However, it still serves a useful function to maintain a “base level” definition of comics. It facilitates discussion, creativity (don’t have to be constantly “reinventing the wheel”) and critical assessment. Prevents the art form from going down the masturbatory path that the “fine arts” went — and thus, made themselves irrelevant to most of the audience — with an “anything can be a work of art” attitude.

———————–

Nick Thorkelson says:

My interest in this issue comes from giving a talk to some art students a while back about cartooning and having them resist my request that they take cartooning seriously, which they expressed by asking me “but isn’t cartooning a ‘cool’ medium”? Not having read much McLuhan, I was a little flummoxed by the question…

————————

Uh, considering the intellectual level of most students (at least of the Boobus Americanus variety), couldn’t they have actually meant “cool” like in “awesomely hip”?

The term “comics” distilled to its simplist definition is sequential art.

Sequential art is a medium, not a genre.

While a wordless comic telling some story is indeed sequential art, the reverse is not true: Artless prose is not a comic. Thus, a Dave Sim 10,000-word philosophical piece is not “comics,” unless he illustrates it in some sequential fashion.

And yes, I think Trajan’s Column in Rome fits the definition of a comic.

I mean simplest, not simplist. Oh, well…

So Trajan’s Column is a comic, the Bayeux tapestry is a comic, but Dennis the Menace isn’t, and all of the New Yorker cartoons aren’t, either. An egyptian sarkophagus covered with hieroglyphs is a comic, though. As well as any chinese writing is comics – aren’t those chinese letters images in a way?

Hieroglyphs aren’t illustrative: they are the parts of a phonetic system.

Chinese ideograms are largely divorced from representation, too, the base drawings being abstracted and subjected to metaphor and paranomasia.

BTW, I actually saw the Bayeux tapestry. It’s comics.

Hieroglyphs aren’t just phonetics. They were originally purely pictoral representations (determinative) and in later iterations, they were used both phonetically and determinatively, depending on context.

Just sayin…

Cartoons:

http://www.oldmagazinearticles.com/pdf/LAMPOONED%20Americans_0001.jpg

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/coldwar/G1/images/c2_s4.jpg

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/16619/16619-h/images/070.png

http://www.punchcartoons.com/images/M/1981.08.05.235.jpg

http://blog.lib.umn.edu/carls064/freealonzo/FarSide-CatFud.gif

Comic Strips:

http://wondermark.com/wp-content/uploads/2007/01/cathy7.gif

http://www.loc.gov/rr/print/swann/artwood/images/03289r.jpg

http://www.comicsfun.com/comicart/albums/comic_strips/DickTracy_12_29_48.gif

Comic Book Pages:

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_550SmHi37X4/S7bXOw8mE7I/AAAAAAAAAdQ/NFw170UZU7c/s1600/cappage1.jpg

http://robot6.comicbookresources.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/ware-sequence.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-1usCMCH_Zfs/T00EJIzGqMI/AAAAAAAAD04/rTDKeDxdljQ/s1600/chris-ware1.jpg

http://comics.drunkenfist.com.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/03/neal-adams-x-men.jpg

…Now, isn’t it readily apparent that those daily comic strips have something significantly in common with the selected comic book pages?

Which the cartoons lack? Note how the rendering of those old “Punch” cartoons even is missing the “cartooniness” which is supposed to make them akin to comics; yet they’re definitely cartoons.

Not that there aren’t border-blurring exceptions — http://blogs.exeter.ac.uk/webteam/files/2009/06/larson_what_dogs_hear.jpg — but the differences as a group are fairly clear.

Jeet: Hmmm. I wouldn’t consider New Yorker gag panels “comics”, they are “cartoons”. They may contain some aspect of storytelling, but still have little in common with, for instance, a Prince Valiant page, issues of Fantastic Four or Scrooge Duck, or a book such as Maus, although these are also products of the work of cartoonists. And comics don’t necessarily have to be the work of cartoonists, since they could take the form of abstract images, paintings, collages or photo fumetti. Comics might be defined as stories told in language interwoven with, or in the form of, sequential series of images, presented as multiple images within “architectural” pages and/or collections of pages, or otherwise larger overall image structures. So, yeah, I think the Bayeux tapestry and Egyptian hieroglyphs have more in common with comics than any single panel cartoon.

That’s Joel you’re talking to, not Jeet!

James (and Mike and AB): I fully understand this argument, and I even endorse it. It’s good to have an understanding of comics that encompasses Tintin, Herriman, Walt Kelly or whatever (cartoony), as well as Martin Vaughn James, Alberto Breccia, Baudoin, Alex Raymond and almost all the realistic drawing styles, photo fumetti, abstract comics etc. (not cartoony). Everything you say makes perfect sense.

The (certainly tentative and somewhat shaky) point that I wanted to make was: If you “put on another pair of glasses” and look at it not in terms of form and structure, but in terms of how reality is represented in the pictures, then you can see another, cartoony, “nebula” or “galaxy”, which would then exclude the non-cartoony comics, but include gag panels, animated cartoons, Saul Steinberg, Al Hirschfeld, and maybe even some drawings by Paul Klee.

A (non-comics-savvy) friend once referred to an animated cartoon (maybe Disney-style) as a “comic” – and I, also having your understanding in mind, immediately thought: No, that’s wrong! An animated cartoon is not a comic. But Noah’s postings on comics as genre have made me reconsider this, and I have been asking myself recently if there isn’t some legitimacy in “confusing the media” in this way, because it points to “another kind of comics”, where it is not defined by the structure, but by the cartooniness.

By saying that I do not mean at all to invalidate the formal definition. I think it is very good to have it, because it also means that as a cartoonist, you are not “imprisoned” in the cartooniness, which is also a necessary precondition for comics to grow up a little bit, and it forces cartoonists to confront themselves with comics that are not comic.

On the other hand, what motivates my argument is that I think that the cartooniness is another aspect of comics that also appeared with the rise of the comic strip, just like the sequentiality, but which is shared by other media which are not necessarily sequential, or still. It’s another “overlap”.

Hope this makes a littlebit of sense.

Gee, I guess my other laptop is so tiny that I saw Jeet’s name when it was not! Sorry Joel. But I still see “comics” as a medium of expression involving multiple images, with or without words integrated into them, and “cartooning” as describing a range of drawing techniques, which might or might not be implemented by people involved in making comics.

I would argue that while gag cartoons are not sequential art on the surface, most of them involve a “passage of time” — a captioned quote, for example — during the viewing process. It is this passage of time that infers sequentiality in a one-panel cartoon.

Yes, there are exceptions. We all know that.

But even in wordless cartoons — those by Orlando Busino, for example — there are often speed lines or movement lines of some sort to infer movement (i.e., a sequential passage of time).

The point is, in most cases, comics are, in fact, sequential art. They are NOT a genre, just as a book is not a genre.

I thought this article was very interesting.

I don’t think its an iron-clad explanation or some perfectly enlightened position to start from, but it does reframe a lot of conversations I’ve had with non-comics people in a way thats not “they have no idea what they’re talking about”.

Perhaps Im approaching this differently as someone learning to make comics rather than an academic. To me it seems that if your trying to arrange symbols in a way that best communicates story and meaning to a viewer than a model that, while flawed, resembles the average viewer’s understanding seems more useful. Even if its just to undermine the average viewer’s understanding.

That being said, I dont think this view of ‘what is comics’ should replace existing views or vis versa. Why not keep both lenses and use them both?

——————-

R. Maheras says:

I would argue that while gag cartoons are not sequential art on the surface, most of them involve a “passage of time” — a captioned quote, for example — during the viewing process. It is this passage of time that infers sequentiality in a one-panel cartoon.

——————–

Certainly, many paintings suggest that “passage of time”:

http://uploads7.wikipaintings.org/images/rembrandt/the-blinding-of-samson-1636.jpg

http://uploads7.wikipaintings.org/images/rembrandt/the-blinding-of-samson-1636.jpg

As do some photos:

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_fQB0v4jYKvI/S8Z472GZlfI/AAAAAAAAADY/w1cNkZayp6k/s1600/robert_capa_dday.jpg

http://media-1.web.britannica.com/eb-media//96/71296-050-6A212E1E.jpg (Photo by Bill Hudson)

However, consider the significant difference between those “flash-frozen” examples and countless others, and works like the following:

http://anticap.files.wordpress.com/2011/01/chevaux-muybridge-sos-photos-traitement-image-retouche-editing-prise-de-vue.jpg

At http://blog.oregonlive.com/visualarts/2008/08/last_chance_eadweard_muybridge.html , we read that:

————————–

Initially a landscape photographer, Muybridge designed and began experimenting in the 1870s with a zoopraxiscope camera, or what was actually several mounted together. Part of his funding came from San Francisco railroad magnate and Stanford University founder Leland Stanford, who hired Muybridge to settle with his zoopraxiscope a long-simmering debate among horse-racing fans: Did a trotting horse ever have all four feet in the air at the same time?

Muybridge’s zoopraxiscope brought more than that answer, which turned out to be yes. It revealed motion itself for the first time.

“He had captured aspects of motion whose speed had made them as invisible as the moons of Jupiter before the telescope, and he had found a way to set them back in motion,” writes Rebecca Solnit in her book “Motion Studies: Time, Space and Eadweard Muybridge.” “It was as though he had grasped time itself, made it stand still, and then made it run again, over and over. Time was at his command as it had never been at anyone’s before.”

Muybridge didn’t invent actual cinema, but he inspired its invention just a few years later.

————————-

Moving on to:

http://welcometotripcity.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/11/cap.batroc.KIRBY_.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_KypEs8uC3b4/TTGlRK6jo1I/AAAAAAAABY4/S7qBWzlL-gQ/s1600/Nick_Fury_002p.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_KypEs8uC3b4/TTGlQ3qBIII/AAAAAAAABYw/g8g4wwks4cI/s1600/Nick_Fury_001_04.jpg

http://forbiddenplanet.co.uk/blog/wp-content/uploads/2010/08/furyshield11.jpg

————————–

Dave Clarke says:

…this article…does reframe a lot of conversations I’ve had with non-comics people in a way thats not “they have no idea what they’re talking about”.

—————————

Oh, they have an idea of what they’re talking about; it’s just a muddle-headed and absurdly imprecise one.

Should we take seriously the “thinking” of those who argue, say, that this…

http://www.ibiblio.org/wm/paint/auth/vinci/joconde/joconde.jpg

…is basically the same as the violet stuff here…

http://lisacall.com/images/2009/03/paint3.jpg

…because they’re all colored pigments applied to a surface?

Why, that “Mona Lisa = latex paint on a wall” argument actually makes more sense than ” ‘The Dark Knight Rises’ is a comic” thinking.

Mike – You got me. You didn’t actually compare comics to slavery. Instead you made the slippery slope argument that if we accede to an attitude where the “popular consensus” is seriously considered worthy to decide that “A” is actually “B,” that lays the groundwork for attitudes such as “blacks are not human beings.” And lays the groundwork for making the institution of slavery morally acceptable, which is not at all the same thing.

In doing so, you proved that consensus isn’t all it’s cracked up to be – we can’t reach a consensus on whether formalist definitions have to reach all the way to from comics to discussions of whether black people are human beings. I understand why you make the point (and I even understand your point), but it’s a much more serious (and thus, false) equivalency than I think is necessary to the topic at hand.