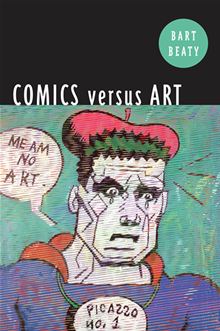

I’m reading Bart Beaty’s Comics Vs. Art. Kailyn already provided a review, but I thought I’d do a number of short posts on it as I went through.

I’m reading Bart Beaty’s Comics Vs. Art. Kailyn already provided a review, but I thought I’d do a number of short posts on it as I went through.

Beaty’s first discussion (in Chapter 2; Chapter 1 is an introduction) focuses on the efforts to define comics over the years. These efforts are…um. I’m a little speechless, actually.

No doubt I’m overly harsh, but Christ, virtually everybody Beaty quotes in the chapter sounds about as sharp as a decapitated pig carcass. I’d always thought that McCloud’s sequential-art (so no single panel comics) formal effort to define comics was a kind of quintessence of stupidity, but compared to his predecessors, McCloud actually comes off looking pretty good. Colton Waugh, for example, says that comics have to have continuing characters and speech bubbles. M. Thomas Inge and Bill Blackbeard — two of the most respected comics critics — also argued that recurrent characters were essential to the definition of comics, even though, as Beaty dryly remarks, “Definitions of comics that privilege content over form have numerous significant logical problems.”

Beaty suggests that Blackbeard may have been motivated less by incompetence than by chauvinism; his definitions were designed to show that the Yellow Kid was the first comic, carefully excising European precursors so that comics could be seen as a quintessential American art form (like jazz without the African Americans, I guess.) Art Spiegelman, to his shame, has also dabbled in this sort of nativist nonsense.

Other writers, though, have embraced comics’ non-American history — by insisting that the Bayeux Tapestry and even cave paintings constitute comics. Then there’s David Kunzle — again, a much respected scholar — who insists that comics must be sequences (no Dennis the Menace) that there must be a preponderance of image over text (whatever that means) that the original purpose must be reproductive (so your kid drawing a comic isn’t your kid drawing a comic) and that the story must be both moral and topical, which doesn’t even merit parenthetical refutation.

Of course, there are reasons that so many respected scholars in this field have so determinedly spouted nonsensical gibberish. Mostly, as Beaty argues, it has to do with status anxiety; the hope is always that the next definition will make comics worthwhile, either by emphasizing their quintessential American vitality or by showing that they have been art since the first wooly mammoth drew the first hominid on the cave wall. Still, it’s hard to escape the sensation, reading through this chapter, that comics scholars today stand on the shoulders not of giants, but of infants. Beaty doesn’t quite come out and say so, but such ineffectual flailing disguised as scholarship seems like it has to have been deligitimizing rather than ennobling. If comics can’t generate more thoughtful criticism than this, then maybe it really is a debased form best ignored.

At least Les Daniels, whose Wonder Woman scholarship I admire, comes off looking good. Beaty quotes him as acidly commenting, “defenders of the comics medium have a tendency to rummage through recognized remnants of mankind’s vast history to pluck forth sanctioned symbols which might create among the cognoscenti the desired shock of recognition.” Nice prose too, damn it.

What, you don’t buy into the idea that the bif, bam, pow, comics which are now no longer just for kids but are now an art form called “Co-mixckzs” must be defined and regulated by old farts who want it to conform to certain strict and stringent standards that are universally recognized in order to properly enter into the adult world? Pshaw.

To be fair, there’s lots of good comics scholarship…and I bet some of the folks Beaty talks about have even said interesting things in other contexts. But, man, reading that chapter was depressing.

Can you list some of the good scholarship? I like Les Daniels too, but I just know his coffee-table books. Solid stuff, but there’s only so much a guy can say in among the pictures.

“there must be a preponderance of image over text (whatever that means)”

We had an argument about this a few years back. I cited those left-wing “[Whatever] for Beginners” books as works that need both words and pictures but still don’t qualify as comics. In a comic people read from picture to picture, with the words there to flesh things out. In the “beginners” books people read from word clump to word clump, with the pictures there to dress things up.

Does it make a difference? Probably not, since most definitions don’t. But I think this distinction is what the “preponderance over text” fellow had in mind.

Still, it’s hard to escape the sensation, reading through this chapter, that comics scholars today stand on the shoulders not of giants, but of infants. Beaty doesn’t quite come out and say so, but such ineffectual flailing disguised as scholarship seems like it has to have been deligitimizing rather than ennobling. If comics can’t generate more thoughtful criticism than this, then maybe it really is a debased form best ignored.

Oh, come on, Noah, this is so much steam-puffing hyperbole. Every scholarly field is defined by the history of its exclusions, its internal arguments, its verities that later turn out to be balderdash, and the sum total of its tactical moves, which all together add up to a generative chaos. Beaty and others, myself included, have devoted much energy to questioning the definitional project (as Aaron Meskin has called it), if by definitional project we mean the search for a transcendent definition that is supposed to apply across all comics genres and cultures. What we need to remind ourselves is that the definitions posited by Waugh, Blackbeard, Kunzle, McCloud, et al., were tactical and local to the needs of their particular projects, whether they acknowledged that or not.

Kunzle’s work is a case in point. Yes, his definition is questionable; yet it enabled his vital historiographical spadework. At the time of Kunzle’s appearance in the 1970s, his work represented a crucial redrawing of the very map of comics–and his definition served to delimit the scope of his study, which is part of what made it possible.

My only complaint about these earlier scholars is that they often presented their local and tactical definitions as transcendent ones. But I can’t fault them too much for that: the field of comics studies was so inchoate, so hopelessly out in left field–so impossible, it seemed at the time–that they had to get themselves worked up in order to get anything done.

Alan Moore on attempts to legitimize comics by finding ye olde antecedents. I’m also reminded of Ambrose Bierce’s bit in The Devil’s Dictionary about freemasons

“Defenders of the comics medium have a tendency to rummage through recognized remnants of mankind’s vast history to pluck forth sanctioned symbols which might create among the cognoscenti the desired shock of recognition.” Nice prose too, damn it.

You’re kidding, right? Let’s look as this gem.

Defenders who rummage through (I’ll guess — trash?) …

No, through remnants (of what? of fabric?) …

No, of … history. Of mankind’s history. Of mankind’s VAST history.

No wait, I forgot that these are *recognized* remnants (recognized by whom?), in which one finds … symbols (remnants of symbols?), which are sanctioned (remnants of sanctioned symbols?). Sanctioned symbols among the recognized remnants.

Indeed, the one word that really *could* use a modifier in this context — cognoscenti — doesn’t get one.

Sure, I’m being pretty mean. But this entire sentence seems to be pieced together from discarded images and cognoscenti-baiting clichés (“shock of recognition”). And as far as I can see, its description of comics’ “defenders” doesn’t even fit the tendency among critics and historians that you are describing.

I will take clear — albeit boneheaded — attempts to define comics in formal terms any day.

Noah, I am as much a pragmatist in these matters as you, but even I can admit that McCloud helped me to think about “comics,” and what I tend to mean when I use that term. Wouldn’t you agree?

Hmm… Charles got here before I did, and said what I was thinking, but with much more class and intelligence. Please disregard my own puffery.

I’d agree that reading about scholarship in numerous fields might well be similarly depressing. This just happens to be where my interest/depression is focused. And…I think I said in the piece that I understand historically why these definitional attempts were made. But (and I’m sure you’ve heard this before, Charles) I don’t necessarily feel the need to grade on a curve. If comics was at a state where nothing better could be done, that doesn’t change the fact that what was done was kind of stupid.

Peter, you’re deconstruction aside, the Daniels’ quote seems perfectly clear to me. For instance, “recognized” seems clear enough to me — he’s saying they’re culturally recognized. It’s an accurate sentiment nicely phrased.

In terms of McCloud…I really was repulsed pretty much from the get-go, I’m afraid. I don’t think he has shaped my understanding of comics in any significant way. I know lots of folks find him valuable, but mostly I wish he’d go away. (At least as a critic; I like Zot.)

Oh…Tom, sorry. Ben Saunders’ Do the Gods Wear Capes is great. Charles Hatfield’s Alternative Comics is very good too (his more recent Kirby book Hand of Fire is much lauded as well, but I haven’t read it.) The book I review here (Bart Beaty’s Comics vs. Art) is very good. I love Anne Allison’s Prohibited and Permitted Desires, which is manga focused and anthropological, but really smart.

Charles and Peter could probably give you more…Peter, have you published anything? I should read it if so….

Tom: Marc Singer’s book on Grant Morrison is good. Obviously YMMV depending on how interesting (not even necessarily “good”) you find Morrison.

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Beaty suggests that Blackbeard may have been motivated less by incompetence than by chauvinism; his definitions were designed to show that the Yellow Kid was the first comic, carefully excising European precursors so that comics could be seen as a quintessential American art form (like jazz without the African Americans, I guess.)

————————-

What a charming way to smear Blackbeard, by dragging racism into it.

————————–

Art Spiegelman, to his shame, has also dabbled in this sort of nativist nonsense.

————————–

And now fervent leftie Spiegelman gets similarly splattered. At least we can be grateful “homophobic” and “misogynyst” did not get tossed in.

Instead of being a promoter of keeping America WASP-y, “the policy of perpetuating native cultures (in opposition to acculturation),” could it not be that this formidably comics-erudite guy simply feels “The Yellow Kid” more fully qualified by his own set of criteria as the first comic, instead of earlier fare from across the ocean?

Even if Spiegelman is wrong — which I firmly believe he is — wouldn’t the explanation for his error be more likely to be “peculiar definition standards” (like R. C. Harvey’s requiring comics to feature verbiage) rather than the jingoistic, flag-waving wish to promote Amerikan culture?

Regrettably, couldn’t find any Spiegelman quotes on the subject; but this site, announcing a Spiegelman lecture on “Comix 101.1,” notes how…

—————————-

Comics as a real mass medium started to emerge in the United States in the early 20th century with the newspaper comic strip…Comics in the United States is usually traced back to the first appearance of the Yellow Kid in the New York World newspaper in 1895.

—————————-

Emphasis added; http://clarke.dickinson.edu/art-spiegelman-2/

Could it be that “The Yellow Kid” gets so much emphasis as a “first” because it truly “got the ball rolling” of comics as an art form with its fame and success, spawning imitators? While other works failed to be remotely as influential?

Cubism is universally noted to have been originated by Picasso and Braque, yet I once ran across a photo of an Aztec artwork made of clipped, colorful feathers that was cubistic as all get-out; not at all the usual Aztec “look.”

Is this to be considered THE FIRST TRUE PIECE OF CUBIST ART, or a work that came out “before its time,” failed to inspire other creators, and thus became an aesthetic irrelevance?

Must Google some more…ah! This essay from “The Evolutionary Review” mentions the usual proto-comics suspects such as the Bayeux tapestry; notes how…

——————————–

…despite eighteenth- and nineteenth-century developments like the series paintings of William Hogarth…or the captioned picture-stories of Rodolphe Toppfer, sequential picture narrative did not emerge in a way that would flourish around the world until [the] Yellow Kid images…combined drawings and words within the drawing, rather than only in captions, in a way that would soon explode into full-fledged comic strips.

———————————-

Emphasis added; from this pdf: http://www.sunypress.edu/pdf/21515778.01.01.19.pdf

The author is wrong if implying “The Yellow Kid” was so technically pioneering; I’ve seen many far earlier cartoons which featured word-balloons, definitely “words within the drawing.” Such as http://paddybrown.co.uk/?p=2082 . However, it was indeed Outcault’s that was the breakthrough work.

—————————-

Charles Hatfield says:

Oh, come on, Noah, this is so much steam-puffing hyperbole.

—————————–

What, you’re expecting nuance?

—————————–

peter sattler says:

Hmm… Charles got here before I did, and said what I was thinking, but with much more class and intelligence. Please disregard my own puffery.

——————————

Oh, but it was tasty puffery!

Charles, incidentally…the problem isn’t just that the definitions are not very convincing; the problem is that the tactical goals are not especially clever either. Promoting comics as uniquely American on the one hand; or convincing somebody that comics are art — those just don’t strike me as especially worthwhile or interesting projects.

I get that you have to start somewhere. But the fact that this is where we started just seems really disheartening and alienating to me.

I agree with Noah on this: the “recurrent characters” thing is too stupid to be true.

I think there’s a case to be made that the Bayeux Tapestry constitutes comics, but I’m curious what the counterargument is – something to do with medium? Cave paintings are a serious stretch, though.

My understanding is that the tapestry is very difficult to read as a narrative, in the first place. It’s also not reproducible, nor meant to be reproduced. And, of course, it doesn’t take part in traditions of cartooning.

The best argument is that it just isn’t usually considered comics, and hasn’t been a strong influence or touchstone for most of the things that we consider to be comics. The best counter-argument I guess is that various scholars have argued for it to be comics.

Domingos has a very useful formulation; he talks about comics restrict-field (which is things that everybody would think of as comics, basically), and comics expanded field (which includes historical and high art analogues from other traditions.) That allows you to talk about ways that things which aren’t usually thought of as comics look like, or might be like, comics in some ways without getting bogged down in status claims or endless and largely pointless formal arguments.

I can see the point of having a category for things that are related to comics but aren’t quite for one reason or another (stained glass windows, Trajan’s column, Renaissance frescos, the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward, etc).

I had no idea that “must be reproducable” was a requirement for comics. Nor was I aware of the “had to be part of an existing tradition” requirement. Those strike me as highly dubious limitations and beg the question of where they originated.

I imagine some outsider artist painting a very nice three panel strip on a wall in East London – if you can take a picture of it, does that count as reproducable?

I don’t really care about reproducibility — it’s one characteristic that’s often cited though. (Even though it has obvious problems.)

I think being part of a tradition or a community is the main thing for me — though remember that traditions and communities are fluid, so things not in the tradition that started to be considered as comics could easily become comics basically just by being recognized as such.

The main point, really, is that getting bogged down in definitions and exceptions is not an especially worthwhile critical endeavor for the most part. If you want to talk about something as a comic, go ahead. If you don’t, don’t. For critics or scholars who have something interesting to say, it just shouldn’t be that big a deal.

One of the things that Neil Cohn suggests at the beginning of Early Writing on Visual Language is that if comics is a language, then it should have some sort of community aspect to it – after all, languages spring up as a way for groups of people to communicate with each other. I have a multitude of issues with Cohn in general, but this was an interesting point.

I’m a Defense contractor and one of the things I’ve noticed after a decade of working in Federal agencies is that each organization has their own dialect (there’s really no better word for it); it’s recognizably English, but there are enough terms and phrases and concepts that it’s not entirely understandable to outsiders. These micro-dialects can spring up around teams as small as four or five people and can be inpenetrable to people who work in the next office.

I mention this because I think there are parallels to what you’re talking about regarding traditions or communities. This small group may think about comics in this way, while a different community may think about it in a completely different way – both are valid (for their purposes) and may share a large degree of overlap, but the overlaps and disconnects are usually where the interesting stuff develops.

And, as always, Eliot’s Tradition and the Individual Talent probably folds in there somewhere.

(Long-time (if intermittent) reader, first time commenter.)

Felt compelled to offer my $.02 in (mild) defense of the “recurring characters” idea. I’m actually finding it intriguing, insofar as I’m reading it as putting the emphasis on “recurring” rather than “characters.” That is, defining serialization as essential to the medium. Not just the work itself but also the circumstances of its publication, a given work existing only (or primarily) in a given moment; comics as “live” performance.

“Mainstream” artists from Kirby to recent “cliffhanger king” Brian K. Vaughn have used the issue break as a storytelling tool no less significant than the page turn or panel-to-panel transition. The Love & Rockets roundtable at this very site a while back showcased noticeable differences between readers who experienced Maggie and Hopey’s adventures in “real time” vs. those who came to them “after the fact.” Or imagine Gasoline Alley without at least the awareness that it unspooled over actual lifetimes–kind of a different animal, no?

I kind of like the idea that Great Expectations in its original serialization was, in some not-insignificant way, a different work than the complete novel in one volume–in much the same way that a recording of a concert is not the same thing as the actual concert. The fact of readers engaging with part one of a story while the artist is still in the process of completing part three is compelling to me: it creates a dynamic between reader and artist that is unreproducible–again, more like a slow-motion live performance than a finished work unveiled.

All that said: if you’re looking for a definition that encompasses everything that we call “comics” today, then obviously it falls short. But the thing it does define (i.e. comics series) is maybe worth engaging with as something at least slightly different from standalone works.

(Caveat: I’ve read neither Beaty’s book nor the Blackbeard and Inge works referenced–so I’m not sure if the above is in fact what they had in mind or my own invention. So take this less as a defense of those critics and more as a potentially interesting tangent to explore…)

I’m not sure where Noah is getting his nativist attack on Spiegelman from. Anyone who’s seen Spiegelman’s comics 101 lecture or done much reading about him knows that he posits Rudolph Topfer as the first modern comics cartoonist. Any claims about the Yellow Kid are likely related to it being the first mass-market comic.

I agree that many of these definitions are just plain stupid and essentialist in a way that fails even the basic form of an essentialist argument. But Charles makes a valid point that comics’ status as an art that’s neither fish nor fowl gives it a slippery quality that’s frustrating for historians and others trying to pin down scholarship. “Comics: I know them when I see them”, though intuitively true, is not exactly a satisfying definition.

I’m getting it from Beaty, who quotes Spiegelman. Perhaps Spiegelman’s changed his mind?

Comics isn’t any more hybrid than ballet or opera or film. It’s low status makes it seem incongruous, not the other way round.

Yes, I think he has, but he has repeated quite often the canard that comics are a “unique American art form”.

As for The Yellow Kid being the first mass-market comic that’s also false. There were many of those, especially in Europe, before Outcault ever put pen to paper.

Bets that he changed because of Chris Ware’s interest in Toppfer?

No, I’m quite positive that Spiegelman was aware of Töpffer before Ware — he’s been talking about him for many years. I’m not quite sure how he reconciles Töpffer with the nativist idea, but I do believe he has dropped the latter a while back.

No, no; I’m sure he knew about him. The question was did he give him theoretical weight. I bet the fact that Ware’s made him a forefather means he can’t be ignored…or that there’s more benefit to recognizing him “officially” now. Topffer/Ware can be seen as making comics art at this point; there’s no need to fall back on the (different) validation of nationalism.

I think you’re projecting a bit here — Spiegelman is perfectly capable of reaching that conclusion without Ware, as I’ve understood him from interviews etc. for the past two decades. Also, I’m not sure what theoretical weight Ware has given Töpffer — he seems quite uninterested in the nativist idea and just plain likes Töpffer, far as I can tell.

I’m kind of going off of Beaty’s book here; his last chapter is on Ware, and he talks about how central a figure Ware has been in establishing comics as art. He also talks about how Ware’s work recuperating/ensconcing Toppfer has been in part about establishing/ensconcing Ware himself; creating his own genealogy, in other words (which is something lots of writers do, of course.)

Beaty suggests that Ware’s self-presentation is extremely canny — or at least, extremely effective.

I’ve got another post coming where I’ll talk about it a little more maybe….

Noah,

I’m sorry that I can’t go into more detail here (finals week in full swing), but your Spiegelman/Ware/Töpffer claims are just wrong — which means that Beaty might be wrong too.

Spiegelman was giving pride of place to Töpffer — historically, artistically, and theoretically — at least since 1988, five years before McCloud and when Ware was best known in comic book stores for “Floyd Farland: Citizen of the Future.”

Just take a look at Art’s still very strong “Commix: An Idiosyncratic Historical and Aesthetic Overview” from PRINT, which is itself (I think) a write-up of the art-museum presentations that he had been developing at the time. That essay leads with Töpffer, with his work, his definitions, and his semiotic insights about cartooning.

Ware, on the other hand, didn’t — as far as I can recall — talk in any depth about Töpffer until his 2008 review of the Kunzle collection and monograph.

There’s a lot of revisionist critical history here (including the history of “essentialist definitions”), but I’m not sure what is motivating it.

I’ll check to see what Beaty says exactly…it was me speculating about Ware’s influence though, not him.

Are you claiming that Spiegelman doesn’t refer to comics as a quintessentially American art form? Because then you’re contradicting both Matthias and Beaty….

Ah, here we go. It’s on page 28 of Beaty’s book; quoted from a NYT review of Blackbeard and Williams’ anthology Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics. Spiegelman said:

So, either he’s not considering Topffer to be comics at that point (1977 (Update edit: sorry, that should be 1979), or else he’s engaged in some sort of complex process of doublethink. Either way, I don’t know how that passage can be considered anything other than horseshit. (And that’s not even considering the claim that film is an “indigenous form”, which I think is a pretty thoroughly dicey claim as well.)

Beaty’s overall project and investments are a little unclear. His specific point here, though, is that comics definitions have often been used to try to elevate the medium by presenting it as especially American, and therefore worthy of study/interest. Or, as he puts it, “This appeal to a patriotic conception of comics history bypasses discussion about the aesthetic qualities of the form in favour of a heroic narrative of comics as the hardy underdog struggling against the tyrannical forces of legitimate art. This mimics an image of America itself as the hardscrabble black sheep spawned by its European parents.”

I think that’s a palpable hit — and intended to be one.

The low point of this nonsense I think (thought Beaty doesn’t mention it) is when Spiegelman in Shadow of No Towers nostalgically refers to the good old days of comics and their “gleeful racism”. When you’re holding up white supremacy as an example of your artform’s folksy authenticity, it’s really time to step back and reconsider what the fuck you think you’re doing.

Peter: Bart Beaty’s book is motivating these comments. He does the historical overview of essentialist definitions of comics that motivated Noah’s post. I think that Beaty is quite accurate. I’m not sure if I follow your revisionist claim.

Argh…sorry. Thinking about Shadow of No Talent makes me cranky.

Matthias and Peter, since you both think that Spiegelman started deciding to include Topffer as a comic before Ware led the way, I’m willing to bow to the consensus. I do wonder whether he had a moment when he changed his mind? Whether he discovered Topffer? Or whether his claims for comics as an American art form are just sort of purely reflexive, and so he’s never thought about the fact that Topffer vitiates the case?

I do think you could probably make a case for superheroes as a quintessentially American genre…though probably Spiegelman isn’t all that interested in doing that, I’d guess.

As you note, that quote is from 1979 when few comics people besides Kunzle were aware of Töpffer’s comics. (Some of them were children’s classics in the Eatern Bloc countries, but clearly didn’t make it into comics academia in any major way on account of that). My totally unfounded theory is that Spiegelman probably changed his mind when he read Kunzle’s groundbreaking volume on 19th-century comics. I don’t know that he has repeated the nativist idea since, but somebody here — Peter? — may be able to set the record straight on that.

Sorry, Kunzle’s volume came out in 1990 and as Peter noted Spiegelman started talking about Töpffer in 1988 at the earliest. I got my chronology wrong here…

The idea of recurrent characters always struck me as only making sense in the “recurrent from panel to panel sense”—Showing the same figure over and over again could conceivably be helpful in separating (for instance) a bunch of paintings somebody just propped up next to each other (“juxtaposed sequential images”) and images meant to be juxtaposed and/or telling a coherent narrative.

It still probably is wrong, but it does indicate something typical of comments…the repeated drawing of the same (or nearly the same) images.

Should say “typical of comics”–

“Typical of comments” is typos.

Hi Noah at al.,

I do think it’s fair to say that, to this day, Spiegelman’s narrative about the history of comics retains a sense that American comics added a certain anti-art vitality and anarchistic spirit to the medium, at least in the world of newspaper supplements. (Seldes, Warshow, and other early comics critics had been saying the same thing for decades.)

I doubt he would any longer say, as he did in 1977, that “this art is ours” — at least in those terms. But Spiegelman did like the idea of early cartoonists reveling in their lowbrow aesthetics, even as newspaper moguls were hoping to use the supplements to disseminate color reproductions of European masters (or even just European cartooning).

But back to the 1977 quote.

First, you must remember that, back then, one of the most common just-so stories about comics was that “American comics suck; Europeans are the only ones who truly embrace the art form — living in a comics utopia where bookstores sell them and adults read them on the subway!” The SMITHSONIAN collection was the *only* work out there making a compelling visual case for the vital artistry of early American comic strips. As Ware often reminds us, American comics fans and scholars in the 1970s and 80s would pour over that book, as if it contained pages from a lost codex. It was, in a sense, all we had.

But in his work life, Spiegelman was no stranger to the European tradition. His 1988 article (based on a 1986 lecture) gives as much space to Töpffer (the “Patron Saint” of comics) as it does to McCay. It gives two sentences to Outcault.

And I just looked into Rusty Witek’s “Conversations” volume online. Spiegelman was trumpeting Töpffer in a 1980 interview (“Töpffer was responsible for American comics”), just as RAW was emerging as a home for European comic artists in the United States. And ARCADE, too, occasionally devoted pages to its Euro-ancestry, didn’t it?

So what is left to argue? I think one could claim that the Spiegelman’s story of America taking comics and remaking the form, essentially, in the country’s own image (our “bastard child of art and commerce”) is overblown or historically inaccurate. But it really says little more than that, for a span, American-style comics *became* comics, just as American movies became “the movies.” And if you believe in anti-formalist definitions, you may have to give this story some credence.

And to say that such tendencies go hand-in-hard with blinkered artistic nationalism, at least in Spiegelman’s case, simply doesn’t fit the facts.

***

I’m all out of time for the moment. I’ll have to talk about what I take to be the “revisionist” history of formalist definitions later. But I would say, in brief, that such definitions were never that important as ways of defining what was “in” and “out” of the field of comics.

Even people influenced by McCloud, for example, were almost always interested in his anatomy of “transitions” or in the way he explored the effects of “space” on the experience of “time” (e.g., skinny panels, stretched panels, borderless panels). I cannot recall anyone — including McCloud — ever really caring that much about the “Family Circus” question, other than his detractors.

On the other had, even if comics criticism *did* go through a period of formalist intensity — and even if all these strict formal definitions turned out to be wrong, the whole enterprise doomed — I don’t see that such a tendency indicates anything bad about comics criticism and its history, or even about the tactical/intellectual utility of those erstwhile definitions.

Early twentieth century literary theorists (say, Russian formalists and Prague structuralists, so-called) dedicated their lives to identifying a line between “literal/referential” and “poetic/figurative” uses of language. That particular set of distinctions now seems misbegotten — or at least always open to “What about Family Circus” style objections. But I continue to find their work to be invigorating and engaging, helping me to think about how what we call “literature” works.

You may think that McCloud is not helpful. But the fault is not in his formalism per se. And, I would add, it never was.

[Ugh. Now I’m late. Please accept my pre-apologies for all the typos that certainly litter the above paragraphs.]

Beaty’s not interested in calling out formalism per se. The popular way of perceiving comics as quintessentially American is historical, not formalist, after all.

Rather, Beaty is interested in what critical preoccupation with defining comics has meant, and how it’s related to the effort to make comics art, or to see them as valuable. Basically, you could say he’s looking at the way that various critical projects line up with, or abet, or are influenced by various advocacy projects. He doesn’t exactly make the last leap to say that the impulse to advocacy has tended to make critics say really stupid things — that’s me. I still think it’s true, though.

My main complaint about McCloud’s book doesn’t have anything to do with his formalism, actually. It has to do with the fact that his cartooning in Understanding Comics is unendurably ugly, and that there’s something really troubling about having (one of) the central theoretical text in comics studies be such a hideous example of the form.

Fair enough aesthetic opinion of McCloud, but sort of secondary to the point of your post, don’t you think? After all, you didn’t call him a bad cartoonist. You called him an idiot.

Well, you can’t say everything all at once!

I think his definition is idiotic…though like I said, I sort of felt like he looked better in comparison to the other folks Beaty talks about (at least he wasn’t saying that comics had to be moral or have recurring characters.)

Berlatsky blurbs McCloud: “NO LONGER the quintessence of stupidity!” :-)

Honest, I wasn’t faulting you for not providing your complete set of opinions on McCloud or anyone else. Mine are incomplete too. I was simply saying that I had no quarrel with an aesthetic claim.

So if I’ve started focusing on the wrong things, I’ll let it go. At this point, I’m have to admit that I’m not sure whether you hate McCloud’s definition because it’s a *formalist* definition or because it’s a *bad* formalist definition.

More just because it’s a bad definition, I think. I’m not sure how you could get a good formalist definition — probably by making it more limited and being pretty insistent about those limits? I don’t know; are there any good formal definitions of comics?

—————————

Rob Clough says:

I’m not sure where Noah is getting his nativist attack on Spiegelman from. Anyone who’s seen Spiegelman’s comics 101 lecture or done much reading about him knows that he posits Rudolph Topfer as the first modern comics cartoonist. Any claims about the Yellow Kid are likely related to it being the first mass-market comic.

—————————

Thanks for that info! My Google’ing failed to turn that detail up, and my aging memory (I have that “Commix: An Idiosyncratic Historical and Aesthetic Overview” from PRINT that peter sattler mentioned stashed away in one of the bookcases) did not cough up the needed data.

—————————–

peter sattler says:

There’s a lot of revisionist critical history here (including the history of “essentialist definitions”), but I’m not sure what is motivating it.

——————————

The “usual suspects”? Inaccurate memories, axes to grind, ego, dunderheadedness, misinterpretations…

From a letter by Charles Darwin to another scientist, quoted in the foreword to “The Hedgehog, the Fox, and the Magister’s Pox” by Stephen Jay Gould:

——————————–

I see…that you fulminate against he skepticism of scientific men. You would not fulminate quite so much, if you had had my many wild-goose chases after facts stated by men not trained to scientific accuracy. I often vow to myself that I will utterly disregard every statement made by any man who has not shown the world he can observe accurately.

——————————–

Pingback: The Definition of Comic is "Superhero Film"