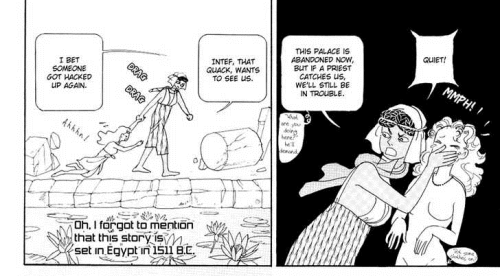

A friend tipped me off to this manga, by Year 24 artist Yamagishi Ryouko. Hatshepsut belongs to the old-school of shoujo in which, quote, “batshit crazy girls go to ridiculous lengths to FOLLOW THEIR DREAMS (or whatever).” There are two stories in the volume, neither of which is officially translated – and for good reason! The images in this post will therefore be from scanlation, courtesy of translation group Lililicious. BTW, while the manga is not pornographic, it is both erotic and taboo-breaking. You should consider yourself warned. With that out of the way, we can proceed.

First, some background I was able to glean from the internet: According to her English wikipedia page, Yamagishi Ryouko is best known for stories with supernatural and erotic elements, drawn in an Art Nouveau style, about Russian ballet or classic folklore. She’s also the author of possibly the first published yuri manga. For the purposes of this post, what really matters is that she has a number of other Egypt stories to her name. These include Sphinx (1979), Tut-ankh-amen (1994 and 1996) and Isis (1997). The author’s enduring interest in ancient Egypt perhaps explains the great attention to period detail in Hatshepsut (1995), in which the figures actually resemble Egyptian art at times:

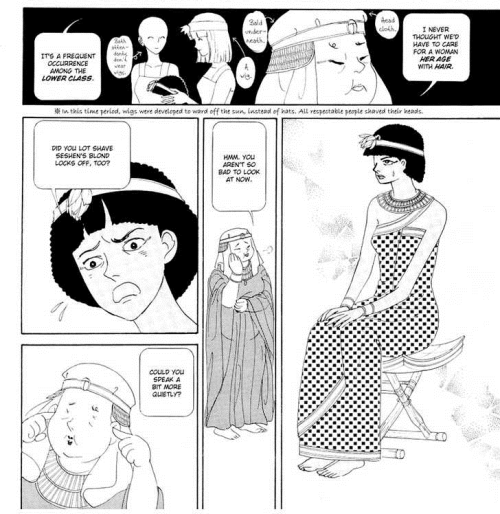

I read a movie review once that said that if the script for Gladiator had been written by a woman, there would have been more attention paid to people’s dress and hairstyle. In fact, the author makes a point in Hatshepsut of paying attention to these things. Characters change hairstyle and clothing in response to changes in station, age, and presented gender. There are other details, too. When a character is drugged, it’s with mandragora. A legitimate successor is preferred over an illegitimate one, but marrying a half-sister can strengthen your claim to the Godhood. At one point Ryouko Yamagishi even works an anthropological explanation for the Cretan Minotaur into the story – but I’ll get to that later. I want to first talk about the opening story in the volume which, in classic Year 24 tradition, is deeply inspired by another Year 24 work.

THE ONE AND ONLY FEMALE PHARAOH IN AN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN DYNASTY

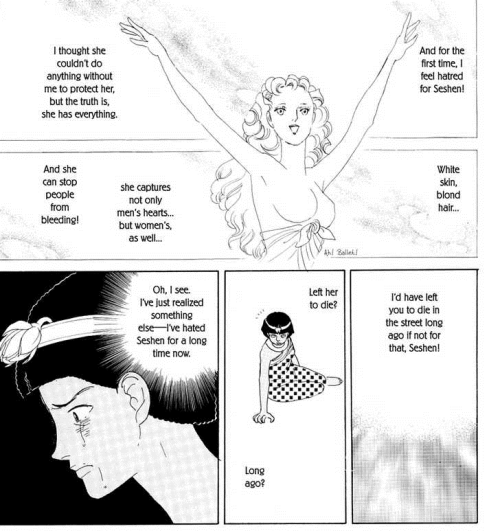

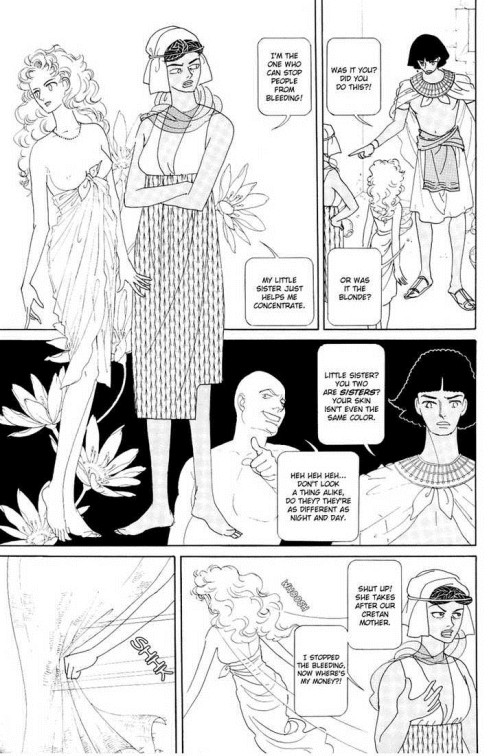

You see, there are two sisters in this story. One is beautiful, emotional, passionate, but brainless. The other is shrewd, ruthless, practical, and ordinary-looking. Of course men all prefer and are in love with the beautiful, lustful sister. Sounds familiar, right?

The sisters look so different that one wonders if they are really full biological sisters. The story says that they are: their father, now decreased, had the power to stop blood from flowing and the power to see the future. The beautiful brainless sister has inherited his blood-stopping abilities, while the more practical, uglier sister has the ability to see the future.

The split of talents reminds me of SF parable Fingers by William Sleator, in which the genius pianist Laszlo Magyar is reincarnated into two brothers: one of whom has the “hands” (a piano prodigy at age five) and the other of whom has the “brain” (composing music for his brother and teaching him musicality). Because the talent is split, each needs the other.

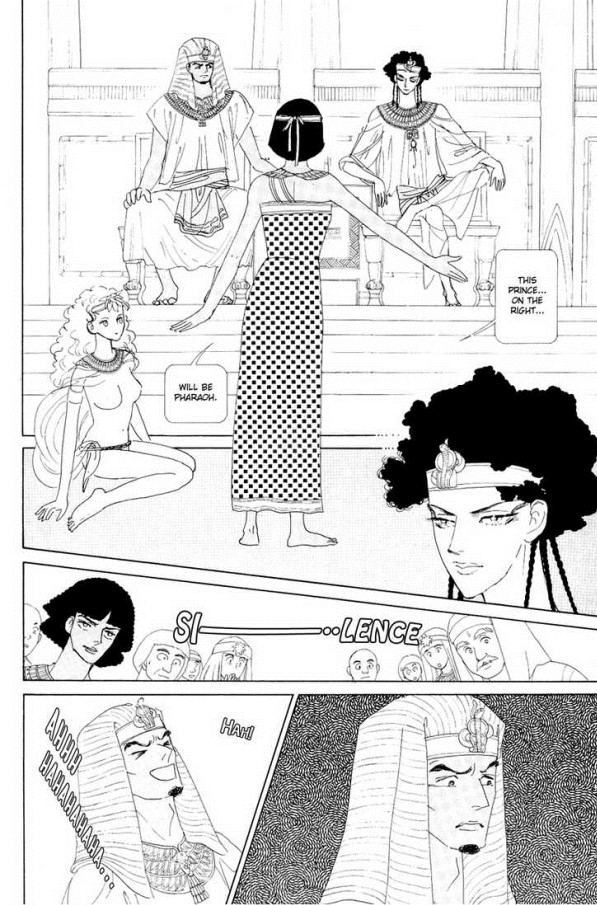

It’s the same situation in this story. The beautiful sister might be brainless, but she’s their primary asset: not only because she has the mystical ability to stop blood, but also because her ability to have strong emotional outbursts is helpful in their second career as professional mourners. The long-suffering older sister’s ability to see the future, meanwhile, is next to useless. The one time it manifests, in a premonition that Hatshepsut will be Pharaoh, no one believes her. The manga ends with a shot of the older sister dying alone and impoverished, still not believed even after the prophecy has come true.

When talents are “split” between an unworthy sibling and a golden child, it calls to mind splitting as a psychological concept. In this case, the parent sees one child as “all good” and the other as “all bad” (or alternately idealizes and devalues a single child).

Speaking of a single child, if this story hadn’t had that parallel with Hagio’s Half-Drawn – see Noah’s previous post – this probably wouldn’t have occurred to me, but: what if those sisters aren’t separate people at all?

Unlike in Hagio, there’s little evidence within the art to support this conjecture. I can only argue from within a logical framework: as a single person, the younger sister might represent the emotional, animistic, lust-driven self that exists only in the present. The older sister, meanwhile, is not only the rational self, but the self that is “cursed” to see the future, and to plan for it. No one likes her, but she’s the self that keeps their show on the road: that makes sure they are paid and that they’ll be able to eat. The beautiful sister couldn’t exist without her; in a way, the beautiful sister doesn’t make sense without her.

Or maybe not. After all, there’s a perfectly good reason within the story for them to be always together: on his death bed, their father told the older sister that she and no one else was responsible for her younger sister. In that moment, and probably before, they became an inseparable unit. The younger sister is the way she is because the older sister is there. The older sister is the way she is because the younger sister is there. For all intents and purposes, they are a single unit, even if they are really separate people.

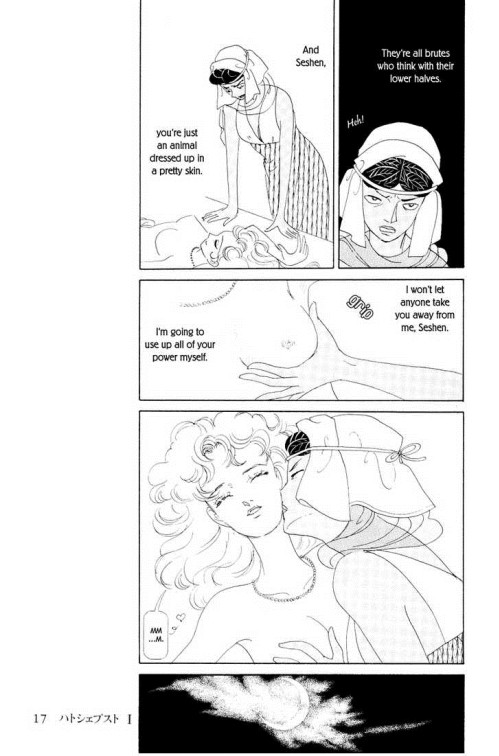

Depending on your perspective, their inseparableness makes this scene either less of an issue, or more disturbing:

If they’re the same person, does the older sister love the lustful, brainless side of herself, even though it’s a pain and a burden? If they are different people, does she love her beautiful brainless sister because she is the one in control of their joint destiny? Or perhaps in the world of Hatshepsut, beauty is a kind of power, and we should love and respect that power for its own sake? Of course, if you saw the panel at the top of the post, or have read Hagio, then you will know that the Brains does resent the Beauty, after all.

OK, enough psychological realism. Despite all the period detail, this isn’t meant to be a realistic story. Probably the best way to see that is just to consider that the younger sister is blonde! Since there are a lot of other (presumably correct) period details in the manga, I tried to look up whether “blonde hair” really was considered attractive at the time of Hatshepsut (circa 1480BC), as is claimed within the story. This proved to be very difficult because white supremacist cranks love to talk about how the ancient Egyptians were actually blonde Europeans. I couldn’t find any real evidence. Did the author make a mistake here? Perhaps it comes from the fact that prostitutes in ancient Rome were required by law to dye their hair blonde? All I know is that T.E. Lawrence and Lawrence of Arabia have a lot to answer for. Not all princes of the desert are blonde!

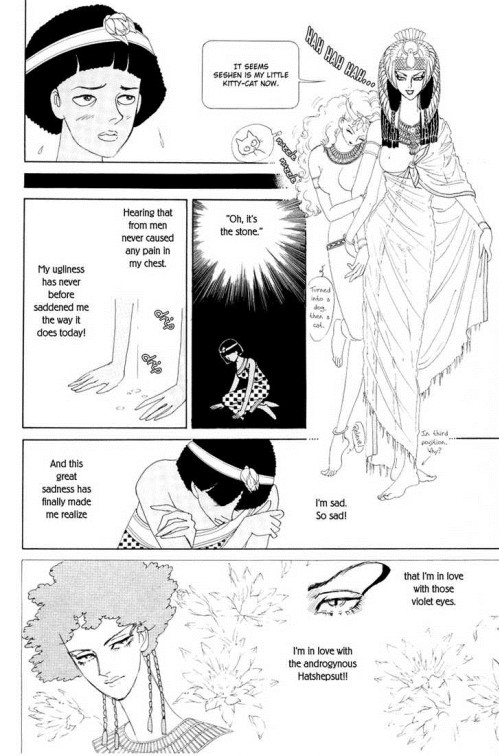

So these two sisters, representing perhaps two sides of a single personality, meet Hatshepsut, who immediately claims the younger sister as a lover. However, they later run into some bad luck and are executed. It’s a brutal and unforgiving world, and Hatshepsut, by becoming the ruler of this world despite her birth gender, is the most brutal and unforgiving of them all. S/he is also, in keeping with the theme of beauty/sexuality as power, the most alluring:

The next story attempts to answer the question of where Hatshepsut’s allure and ambition might have come from.

MINOTAUR

The Minotaur of the title is the Minotaur of ancient Crete. This story hinges around the actions of a Cretian princess staying at the Egyptian court. Incidentally, because Ryouko Yamagishi works without assistants, there’s very little screen tone or shading in Hatshepsut; backgrounds are minimal and figures are drawn in a cartoony style or in outline. The priestess is an important figure, and we can tell because her robe is filled in:

She’s also noticeably foreign compared to the other characters in the manga.

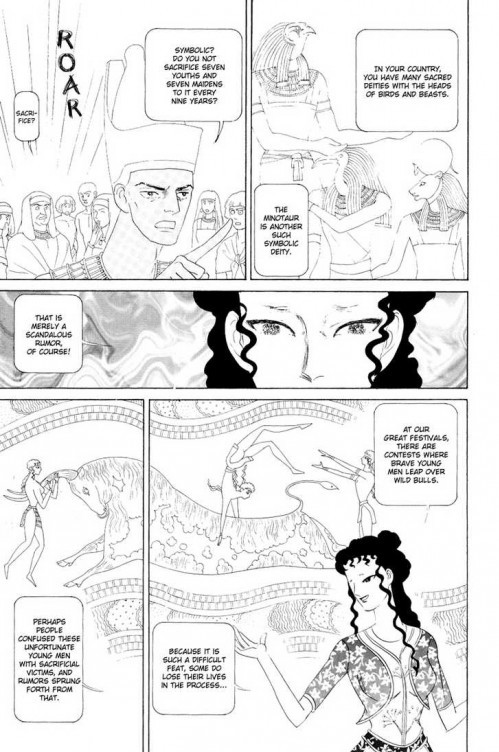

Right away, it’s clear that the priestess has some nefarious purpose in mind – that there’s something unwholesome about her. Rumors begin to circulate at the Egyptian court about children who have gone missing from other courts during her stays there. Eventually, the gossipers hit upon the idea that she has come to Egypt to kidnap children of noble birth, who will be brought back to Crete and fed to the Minotaur. The priestess explains that there is no Minotaur, that it’s all a misunderstanding:

This is what I mean about research: it’s the kind of explanation you’d find in an anthropology book.

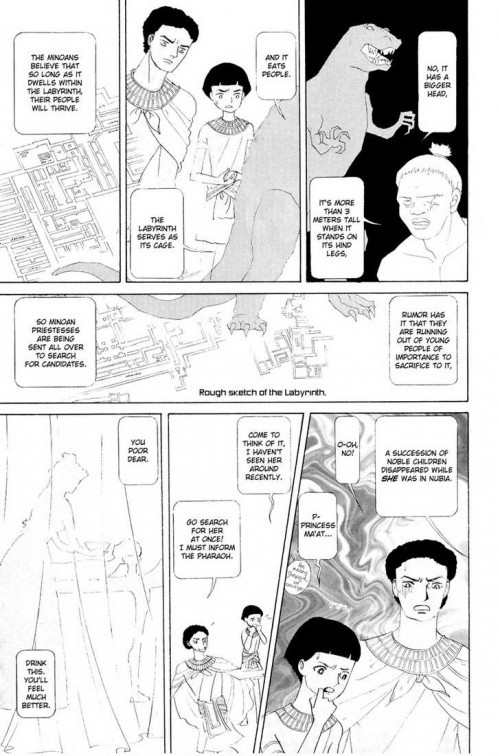

The Minotaur, as it turns out, is a red herring. I might as well get the most hilarious thing about this story out of the way early:

Yup, the Minotaur is actually Godzilla.

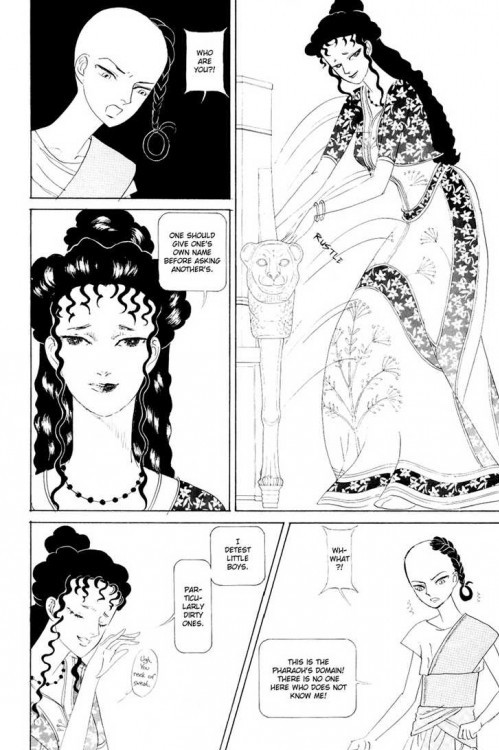

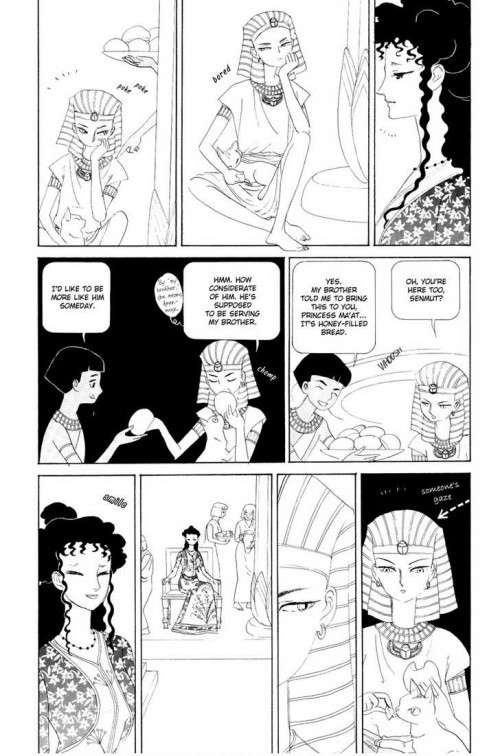

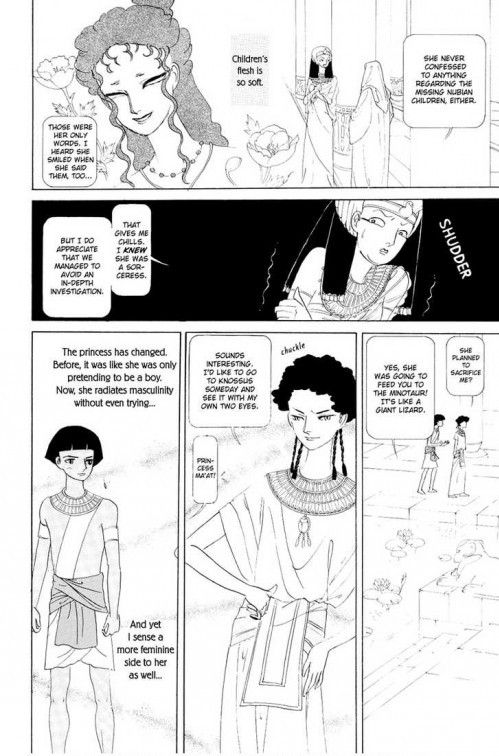

With that out of the way, we can return to trying to take this bizarre short story seriously. One of places Ryoko Yamagishi shows her strength as an artist is through the conveyance of character through clothing and body language:

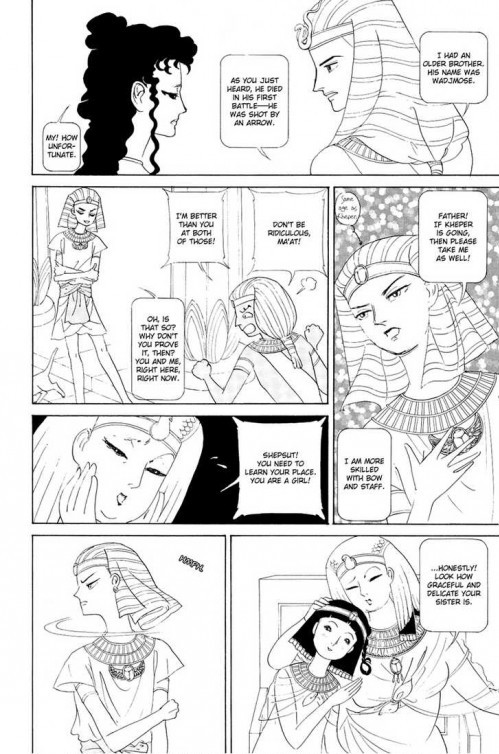

The young Hapshepsut is kitten-like. She doesn’t want to be a girl, so she dresses in a boyish style and keeps her hair cut like a boy’s. She’s successful: strangers see a little boy, not a little girl. It’s explained that the boyish Hapshepsut has been indulged in this way because her older brother, formerly the Pharaoh’s favorite, died in battle on the day she was born. However, when Hapsheptsut officially becomes a woman, the time for fond indulgence will end and she’ll be expected to act properly: to be pretty and docile like her half-sister, and to marry her half-brother, strengthening his claim to the throne. Tagging along with the men on a military drill, the young Hapshepsut thinks wistfully that if she were really a boy, her father would pay more attention to her.

The most unfair thing about all of this is that Hapshepsut is even a better boy than her half-brother is:

All of this so far has been a fairly standard critique of rigid gender roles and of limited roles for women. For a boyish child like Hatshepsut to play around with gender is not considered to be a big deal. The tomboy Hapshepsut is not yet the androgynous charismatic charmer we met in the previous story, and certainly not the ruthless power player we know from history. What happened?

Yes, this is a rape. It’s even more disturbing in context: on the previous page, Hatshepsut is distraught because she – he? – has just had her first period. >_> Once you know, you can see the hints the author was dropping earlier on. But on first read-through, this is shocking.

There’s a long and venerable tradition of rape as a transformative plot device in Japanese novels and film, of course. Generally, the raped woman (I think it always is a woman) is transformed into a Bodhisattva able to accept the man who raped her, as we all meditate upon themes of universal forgiveness and cosmic love. Wings of Honneamise is a notable example, especially as it nearly universally critically praised. Please Save My Earth explores this theme at some depth.

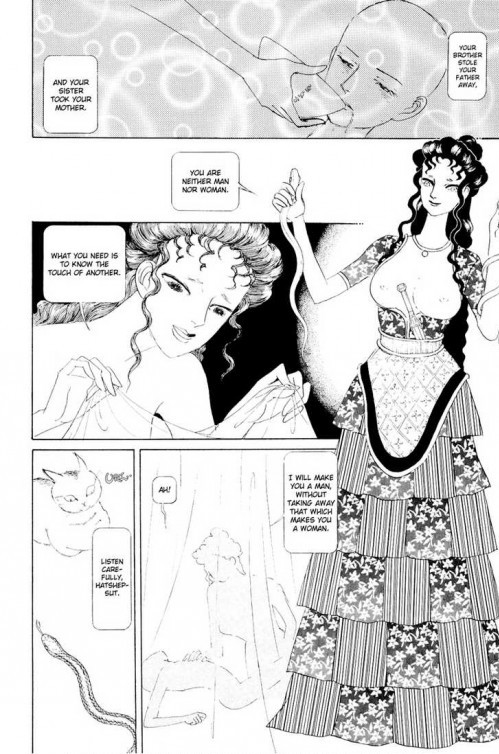

In this case, the effect is somewhat different, as the priestess claims to have – through the mechanism of rape – made Hatshepsut a man. It’s an absolutely bonkers reversal of a plot device traditionally visited on women. The scene itself combines masculine and feminine in a weird way. Hatshepsut is terrified but is forcibly brought to orgasm. She becomes “a man” on the same day that “she” became “a woman.” There’s also an element of being inducted into an arcane mystery – the cat, the snake – as well as, of course, the fact that the “ceremony” was officiated by a priestess.

The priestess is a chaotic force within the story. She drops hints that lead to the death of Hatshepsut’s older brother. On top of that, she’s creepy:

It’s through the traumatic event of the rape that Hatshepsut’s transformation into the beautiful, androgynous, powerful and ruthless Hatshepsut we saw in the first story is begun. Her forced early sexuality contributes to his later charismatic allure – the (female) soft power of sex and beauty. At the moment of climax, Hatshepsut is told that she must become Pharaoh if she wishes to escape the lot of women. This event, understandably, leaves a very strong impression. It’s the catalyst for a personal transformation, explaining the character’s later (male) open ruthlessness. Male and female, in balance, as prophesied and set into motion by the creepy foreign priestess.

In conclusion, this manga will never, ever, be published in English.

The becoming a woman to become a man meme is something else.

I always think about Anne Allison’s book with stuff like this — she argued that Japanese culture in the 80s and 90s created these intense bonds between mothers and sons focused on educational achievement — so mothers were supposed to push, pull, cajole, and force their kids (especially sons) to become successful. The mother/son bond also got eroticized (thus lots of urban legends around mother/son incest, associated with studying for exams.)

So from that perspective you can maybe see a mother figure’s eroticized aid/education being figured such that the recipient is coded male. Education mothers teach their children to be men, so an education mother initiating a girl could be seen as teaching her to be a man.

Oh, I like that!

The historical Hatshepsut is immortalized with a beard in ancient Egyptian art, apparently, so there is some basis to the genderbent portrayal of him/her/etc in this manga, unless that was just a convention when immortalizing Pharaohs.

There also seem to have been other female Pharoahs before and after Hatshepsut, but none who were quite as successful. In any case, the insistence on the androgyny of the main character is one of the more interesting things about Hatshepsut.

There’s a lot of mapping contemporary Japanese social issues onto ancient Egypt going on in general, though, despite all the details about clothing and hairstyle… (and the scenes of the Egyptian court – full of topless acrobats and musicians etc, looks a bit like Andy Warhol’s Factory). In the manga, on the page I couldn’t put up because it’s an explicit underage sex scene, the priestess explains away all those other female rulers of previous dynasties by saying they were technically Pharaohs because that’s allowed in the rules, but really they were controlled by other people because that’s what happens to women. It’s not really clear to me that this was necessary true 2500 years ago in Egypt lol.

But if the female educator is a way to read Hapshepsut’s transformation as having happened to a boy, not a girl, that’s pretty interesting, especially in light of the trans themes in this manga.

Re: the trans issues. A friend and I discussed, when we read this manga, whether Hatshepsut was transgendered, or whether her becoming a man was instrumental (in other words, not an expression of her identity, but because of social strictures placed on women, and she could only wield the authority she desired if she adopted a male role).

This manga is also interesting to consider in light of Yamagishi’s previous manga, the famous Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi, whose protagonist, though male, often pretends to be female for his own purposes, and simultaneously expresses resentment of women. When reading this manga, I felt that in some ways Hatshepsut was an inverse of Shotoku (well, especially since they’re both quite imperious.)

Yeah, I think it’s interesting. I hope someone who knows more about this will comment. I think the manga is a bit ambiguous, especially since it’s emphasized that Hatshepsut is both male *and* female. When Hatshepsut sleeps with the priestess or with the blonde sister, she is drawn *more* feminine than she is the rest of the time – becomes a woman in bed – so to me this seems like it might be more about gender presentation than, like, body dysforia. But I don’t know.

I do think that when expectations for men and women are VERY different, that’s when individuals who otherwise might have been more on the fence are more likely to ‘pick a side’ because they maybe possess traits that don’t fit their assigned gender. And I think that’s the case in Hapshepsut – the roles seem to be very defined, at least for the royal family.

I want to read Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi now!

I suppose I just wonder whether Hatshepsut would have been inclined to take on masculine dress if she lived in a less restrictive society? But this is obviously a hypothetical question without an answer.

Yeah. In the manga, all the characters are pretty insistent that she has a “masculine” bearing and everyone, I mean everyone, assumes s/he is a man (or a boy) at first. Hapshepsut never correct them, it’s always someone else who does that. But I know that Japanese lesbian relationship often have very firm gender roles as well, which makes things more complicated.

The “s” key on my keyboard is busted >_> I’m a native English speaker, I swear…

I’m not an expert on trans issues by any stretch of the imagination…but I do know that trans identities, like gender identities generally, definitely take very different forms in different cultures. Thailand, for example, has a pretty institutionalized cross-dressing male third gender tradition.

I guess the point is, the question, “is this just instrumental or is she (or he) really identifying with the other gender” maybe isn’t the right way to phrase the question. I don’t know that those kinds of impulses can be separated out from cultural roles or cultural opportunities that easily.

Yeah, I completely agree with that. It’s actually what I was saying to Charmian, but then I decided to try to be more politically correct in my reply. Maybe to worse effect, lol.

Oh, I was going to add…I see why you’re saying it won’t ever be published, and I would agree that the chances in the current manga market seem small. It’s possible at some point though that there will be more space for projects like Matt Thorn’s series for Fantagraphics…and if that were ever to happen, who knows?

I think they’d pick a Ryouko Yamagishi work without a child rape scene, though, right? She’s done plenty of others that are more famous. Maybe Hi Izuru Tokoro no Tenshi, the one Charmian mentions (about a folklorish Japanese prince) or Shiroi Heya no Futari, “the first published Japanese yuri comic.”