In a recent post on Philip Marlowe, Ta-Nehisi Coates argues that Chandler’s misogyny is (too) intimately tied to his vulnerability, or fear therof. Coates points to the way that Marlowe turns Carmen Sternwood out of his bed while sneering out lines like “It’s so hard for women—even nice women—to realize that their bodies are not irresistible.” Marlowe’s imperviousness to feminine wiles is connected both to his manliness and to his contempt for femininity.

Coates goes on to say this:

I think to understand misogyny one has to grapple with the conflict between male mythology and male biology. There is something deeply scary about the first time a young male experiences ans erection. All the excitement and hunger and throbbing that people is there. But with that comes a deep, physical longing. Whether or not that longing shall be satiated is not totally up to the male.

Erection is not a choice. It happens to men whether they like it or not. It happens to young boys in the morning whether they have dreamed about sex or not. It happens to them in the movies, in gym class, at breakfast, during sixth period Algebra. It happens in the presence of humans who they find attractive, and it happens in the presence of humans whom they claim are not attractive at all. It is provoked by memory, by perfume, by song, by laughter and by absolutely nothing at all. Erection is not merely sexual desire, but the physical manifestation of that desire.

Men hate women, therefore, because men are supposed to be in control, and their plumbing prevents that control.

I think this is perhaps a little too pat; biology-as-truth is, after all, its own mythology, and one that can (and is) also often put to misogynist ends. But putting that argument aside for the moment, I think Coates is in general correct that manliness is defined by control, and that that control is often structured in terms of control-over-biology, or the body, which is then itself always feminine, or threatening to drag one down into the feminine. Manliness is cleanliness is control is unbodiedness, so that the only real dick is the dick that is secure and private.

If Philip Marlowe read Johnny Ryan’s Prison Pit, you have to think that he would, therefore, be horrified not by its violence or its sadism, but by its messy embodiment — and, therefore, by its unmanliness.

Ryan’s work is, of course, generally thought of as a kind of reductio ad absurdum of frat boy masculinity. Prison Pit is a hyberbolic, endless series of incredibly gruesome, pointless, testosterone-fueled battles with muscles and bodily fluids spurting copiously in every direction. It is as male as male can be.

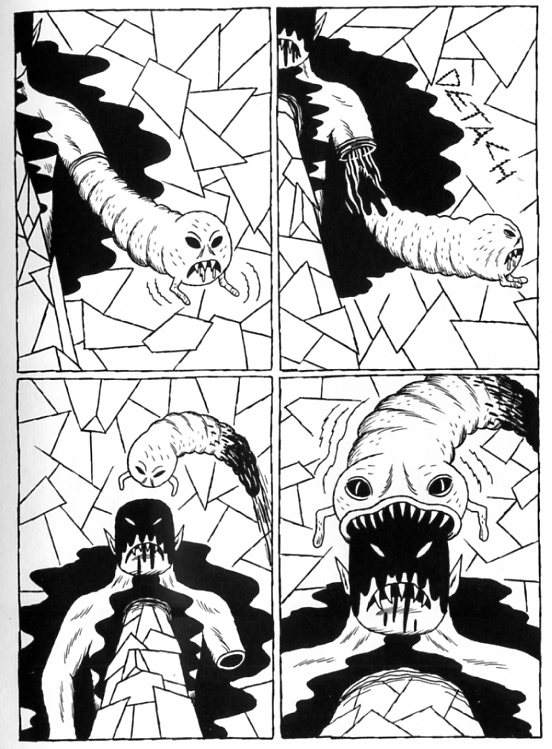

And yet…while Prison Pit is certainly built out of male genre tropes, its vision of masculinity and of masculine bodies is — well, not one that Raymond Chandler would call his own, anyway. That image above, for example, shows our protagonist as his disturbingly phallic left arm oozes up and off and devours his head. Far from being a private dick, that’s a very public and very perverse act of masturbation — and one that is hardly redolent of bodily control.

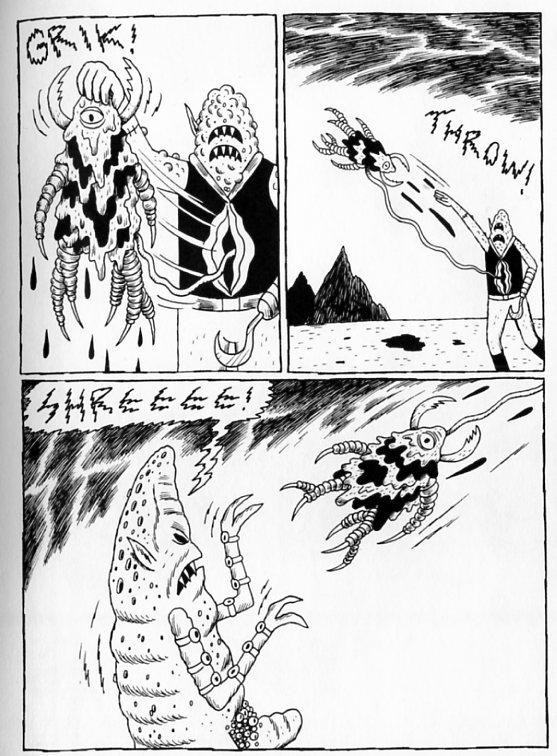

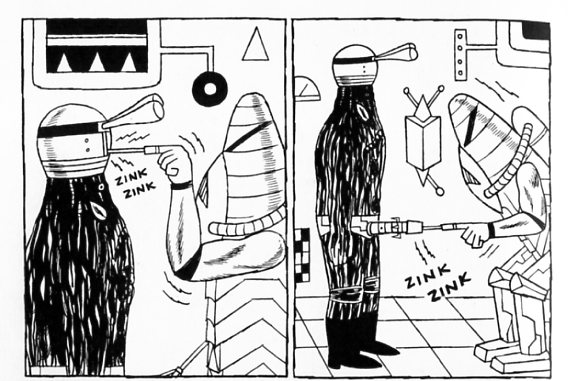

This sequence, while vivid, isn’t anomalous. Bodies in Prison Pit are always gloriously messy, both in the sense of excreting-bodily-fluids-and-coming-apart-in-hideous-ways and in the sense that they are gratuitously indeterminately gendered. Thus, the three-eyed monster named Indigestible Scrotum sports not only his(?) titular spiky scrotum, but also what appears to be a vagina dentata (or whatever you’d call that.)

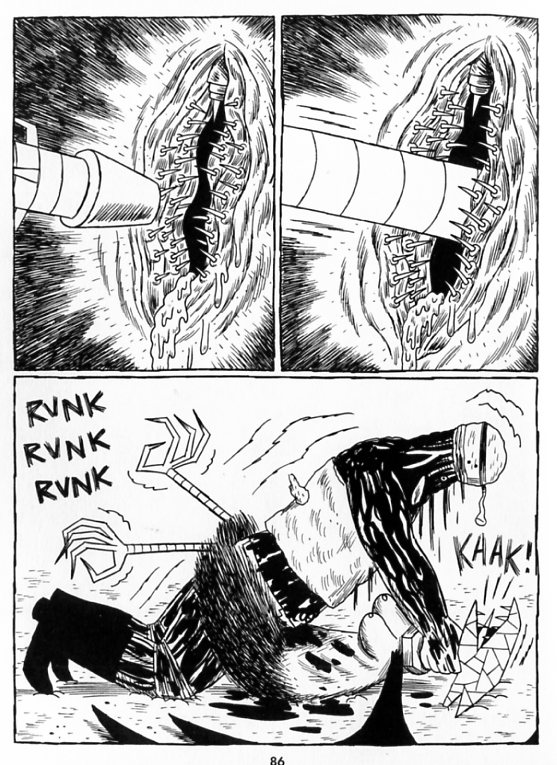

As this suggests, in Prison Pit, sexual organs are less markers of gender than potential offensive weaponry, whether you’re hurling monstrous abortions from your stomach cunt:

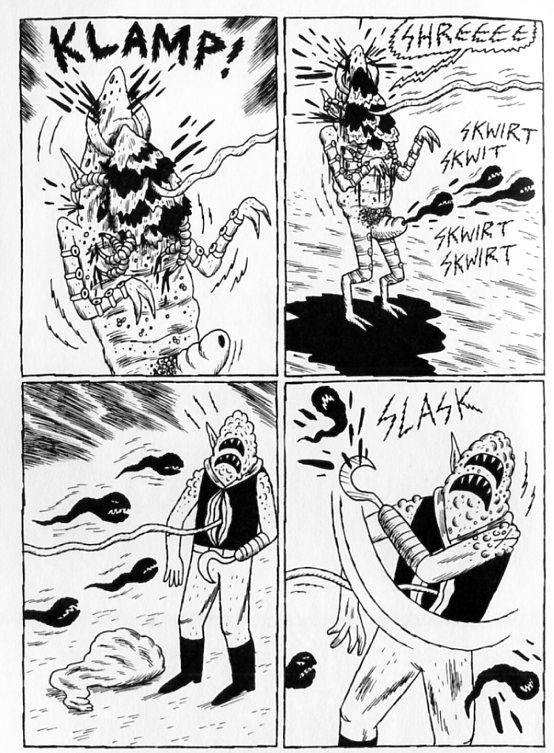

Or blasting monstrous sperm from your sperm-shooter

You could argue that turning sex to violence like this is just another manifestation of a denial of vulnerability, I guess…but, I mean, look at those images. Do those creatures look invulnerable? Or do they look like they’re insides and outsides are always already on the verge of switching places?

This is, perhaps, Marlowe’s hyperbolic anxiety come to life; sex as body-rot and degeneration; desire as a quick, brutal slide into chaos.

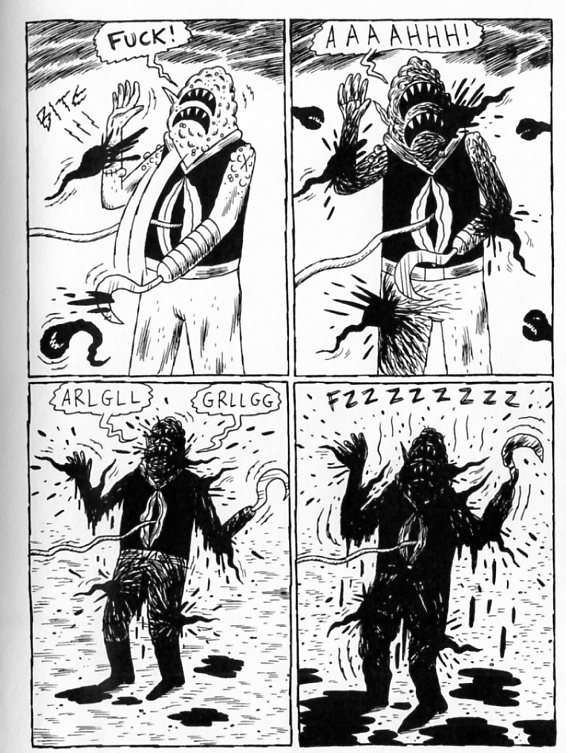

It’s telling, I think, that the one actual act of sex in the first four volumes is a multi-level rape. The protagonist has his body taken over by the slurge — that repulsive creature attached where his left arm used to be. The slurg-controlled body is then kidnapped by another (male? genderless? neuter?) antagonist, who fits him (it?) with a mind-control computer helmet and cyborg penis.

The mind-raped protagonist is then commanded to rape the Ladydactyl, a kind of monstrous feminine flying Pterodactyl.

The robot-on-atavistic-horror intercourse produces a giant sky cancer which tears the Ladydactyl apart. The protagonist finally regains his own brain, and declares, “That fucking sucked.” Which seems like a reasonable reaction. Rape here isn’t a way for man to exercise power over women. Rather for Ryan everybody, everywhere, is a sack of more or less constantly violated meat, to whom gender is epoxied (literally, in this sequence) as a means of more fully realizing the work of degradation.

In Prison Pit, Marlowe’s signal virtues of honor and continence are impossible. And, as a result, Marlowe’s signal failings — fear of bodies, fear of losing control, misogyny, homophobia — rise up and vomit bloody feces on themselves. Whether this underlines Chandler’s ethics or refutes them is perhaps an open question. But in any case, it’s enjoyable to imagine Philip Marlowe dropped into Ryan’s world, his private dick torn out by the roots to expose, quite publicly, the raw, red, gaping, and ambiguously gendered wound.

Without getting into the argument about Chandler’s “misogyny,” where all the predictable drums are beaten…

…does not a huge part of Ryan’s splendid “Prison Pit” depend on the hetero male argument that to take the “receptive,” stereotypically female part in sex is a defeat?

When people say, “_____ got screwed,” “[this group] got shafted,” or even “this argument sucks,” they don’t mean the individuals or groups mentioned were delightfully pleasure, or that the argument gave and received pleasure; it’s all seen in a negative light.

Which regrettably serves to explain a good part of why gay males are seen in such contempt; why when in prison, homosexual activity is made necessary through lack of women, it’s the rule that “he who fucks is gay, he who gets fucked is gay.”

And gives a tragic view of how women are seen by “manly men”…

Anyway, “Prison Pit” is delightfully inventive; his classically restrained compositions and panel construction serving to heighten the madness delineated within.

Surely someone, somewhere has already written of how Rob Bottin’s groundbreaking “body horror” FX in the 1982 Carpenter film of “The Thing” influenced this and many other such works since: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JjIXwkX1e48 ( …All done without computers!)

A nod to Cronenberg’s 1983 “Videodrome,” too: James Woods discovers his biomechanic “cancer gun”: http://www.cyberpunkreview.com/images/videodrome02.jpg . Rick Trembles writes/draws how… http://sequential.spiltink.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/videodrome2.gif

Oops! “…delightfully pleasured.”

Chandler’s misogyny is pretty straightforward. Coates has several relevant quotes. It’s not especially subtle.

Anyway…body horror is usually pretty complicated in its take on gender. People definitely are constantly violently penetrated in prison pit…but like I say in the review, the gender of the person penetrating and the person penetrated are often really scrambled. For instance, the thing with the stomach cunt and offensive abortion weapon, who is presumably female, is attacked by sperm death…which in the next page I didn’t show turns him into a male duplicate of his attacker. So here penetration (of some sort) masculinizes rather than feminizes.

There’s a lot of things like that, I’d argue — enough that it’s difficult to assign any particular gender or role to bodies. As I say, that doesn’t make it a feminist statement — but it is, to me at least, a welcome contrast to something like Chandler, where cleanliness and strict gender boundaries are deployed to protect masculinity from the danger of bodies and women.

I would like some quotes proving his case, but there are none. He also asserts that women were getting hit in Hitchcock’s Rear Window and To Catch a Thief (in the first part), which I’m pretty sure isn’t true at all. A major plot point in the former is about the possible murder of a man’s wife living across the court yard. Jimmy Stewart doesn’t lay a hand on Grace Kelly, and is obsessed with seeing Raymond Burr brought to justice — how is this a sign of misogyny? I haven’t watched To Catch a Thief as much, but I don’t recall Cary Grant hitting any women in it. If he had mentioned Marnie, he might have a case.

Marlowe is something else. He’s hit and beaten up as much or more than he actually hits and beats up others. I’ve always taken his bravado as an intentionally constructed mask for a certain weakness. It’s also what gets him through his adventures. To my memory, he hits women who are in the process of fucking him over somehow, by pulling a gun on him and such. Singling out his hitting some female characters while ignoring all of the other violence of his world seems a bit myopic. It’s important to consider the diegesis, not just select a component and apply real world standards to it. Do the women have agency in the violent narrative? Are they as responsible as any of the men in fostering the violence of that narrative?

Might as well condemn Ryan’s strip for its advocacy of violence, rape, murder and general misanthropy.

Coates makes a pretty tight case for the book’s misogyny, including quotes. I explain in this essay why Ryan’s take on gender and sexuality is really different. You can engage with one or the other of those, or both.

Coates talks about why Marlowe’s bravado and mask are built on and refer to the text’s strident masculinity and fear of/distaste for women.

You do realize that the book is fiction, right? The women in it are not real? So the fact that Marlowe reacts to the way the women behave — he’s not reacting to things happening in real life. The women throw themselves at him because Chandler wants the story to work that way.

It makes my head hurt that we’re arguing over whether hard boiled detective fiction has a problem with women. What qualifies as misogyny in your view, Charles? Does the writer actually have to just write a novel composed entirely of the words, “I hate women” over and over? Except you’d probably argue that that was satire.

You’re allowed to like stories that are misogynist, you know. I like Chandler okay, for that matter.

Also, the issue of agency is almost completely a red herring in this particular context. Chandler ascribes agency to women. The issue is that they’re corrupt and distasteful, not that they’re weak. It’s a misogyny built around hatred of female bodies and female agency. The fact that the Sternwood sisters control are autonomous is a big part of why the world of the novel is so corrupt. Marlowe’s nobility is his ability to shut himself off from the female entanglements which in this novel spell evil.

Feel free to prove me wrong by quoting one of the quotes Coates uses to prove his case. He asserts his position, that’s all.

It’s baffling to me that you and Coates are the ones so horribly offended by Chandler, but you’re asking me if I’m aware he writes fiction. What? I suggested you consider the overall fictional world Marlowe inhabits.

You choose to read The Big Sleep as a metaphor for what happens when women have power. I see it as a story of corrupted women, and those women are a lot more interesting characters than the way women often were portrayed in popular culture. Not all women are treated the same by Marlowe in the course of his adventures, but it’s true that most people are corrupt or twisted in the books. Singling out just the women is because of your own wish to have a … what would you call it? … misogynist utopia.

The culture at the time, both men and women, largely possessed a view of women that is not my own. What we’re arguing about is whether Chandler’s work was worse than his times (not just sexist, but an actually an expression of contempt and hatred of women), or if something like the femme fatale is a step above the typical pop cultural portrayal of women. I think it is, by and large. That doesn’t mean that there are no problems with Chandler, femme fatales, or hardboiled fiction in general. I just don’t like glib dismissals of good literature from wouldbe nannies.

Evidence for your case would be to show a disproportionate amount of violence and negative depictions focused on women in his books and targeted at what Chandler sets up as their femininity. Seems to me that men fared a whole lot worse in The Big Sleep. But that’s never a sign of his hating men to you, is it?

I’m sorry, I just don’t have the heart to copy the quotes in the linked article to make a perfectly obvious point.

Where did I say I was horribly offended? Chandler’s a misogynist and kind of a shit, but that’s the case for lots of writers, including many that I like.

“I see it as a story of corrupted women, and those women are a lot more interesting characters than the way women often were portrayed in popular culture.”

I agree. Doesn’t mean it’s not misogynist. Sometimes committed misogynists create more interesting female characters because they actually care about women, whereas more casual misogynists tend just to ignore them. Chandler’s pretty thoroughly obsessed with gender and female corruption and male honor (as is a lot of noir.) For that reason, his women are vivid.

“What we’re arguing about is whether Chandler’s work was worse than his times (not just sexist, but an actually an expression of contempt and hatred of women), or if something like the femme fatale is a step above the typical pop cultural portrayal of women.”

Nope. Not arguing about that at all, because it’s a completely incoherent statement. The first part has nothing to do with the second. I don’t give a rat’s ass whether his work was better or worse than his times; I’m not giving out brownie points for trying. Whether or not the femme fatale is better or worse than its time has nothing to do with whether or not its a misogynist portrayal. The femme fatale is about fear and hatred of strong women — and often about simultaneous fascination with them. It’s misogynist, whether or not anyone else at the time happened to be more or less so. Again, you’re still allowed to like it. But racing around asserting that it isn’t something that it is because you want to save it is just nonsense. Save it from what? For whom? You really think Raymond Chandler needs you rushing to his defense to tell us all how he was a modern egalitarian? Please.

The problem isn’t that I’m dismissing it. The problem is that you seize up whenever anyone brings up the possibility of sexism to such an extent that you’re unable to read what I’ve actually written. Puritan, heal thyself.

And finally — Coates’ essay is actually about masculinity and Chandler’s discomfort with it. Misogyny for him is intimately related to his understanding of masculinity; so is his homophobia. He doesn’t hate men; he idolizes them — and the idolization often involves contempt for individual men, because that’s how masculinity works. It’s about not living up to the ideal. The attitude towards men and women and bodies and sex is all tied up together. Coates’ reading (on which I’m building) is not about women being singled out. It’s about women being intimately tied into male psychodrama, and what that means for men and women. It’s certainly not a happy place for men anymore than for women.

I mean, if everyone’s corrupt, how do you read Marlowe’s close, immediate bond with the General? How do you read his doubling with the dead man? Why is the corruption especially connected to homosexuals and pornography? In your eagerness to erase gender, you end up being really inattentive to what Chandler’s doing, and to most of the interesting tensions of the book. In the name of saving Marlowe, you render him bland. But that’s what you get when you take the baton from Bowdler, I guess.

Now I’m worried that this has gotten overly heated…. Maybe I can just say that I rather like Chandler? He’s not a favorite or anything, but I like his prose, and there’s a visceral punch that I enjoy — mostly because of precisely the way that it’s tied into his misogyny and his anxiety around gender. His take on those things is noxious…but insightful about the noxiousness, too.

I mean, I’m not trying to censor him or stop people from reading him. It would never occur to me that he needed defending from my reading (or from Coates’.) I talk about misogyny and gender in his work because that’s the bit of his work that interests me, not because I think he should be declared a non-person or anything like that.

————————-

Charles Reece says:

I would like some quotes proving his case, but there are none…

————————-

Who needs evidence?

Thanks to the attitude frequently encountered here, I now take it for granted that whenever a feminist hollers “misogyny,” or even “rape,” the charges are usually baseless. Strictly in the mind of the beholder.

————————-

In contrast to the classical pattern of making the criminal a relatively obscure, marginal figure, a least-likely person, the hard-boiled criminal usually plays a central role, sometimes the central role after the detective. Since Dashiell Hammett first created the pattern in The Maltese Falcon, one hard-boiled detective after another has found himself romantically or sexually involved with the murderess. In other hard-boiled stories, the criminal turns out to be a close friend of the detective, as in The Dain Curse, where the criminal has been in a Watson-like association with the detective throughout the story. In this respect the pattern of the hard-boiled story is almost antithetical to the classical formula. In Agatha Christie, Dorothy Sayers, and their fellow writers, sympathetically interesting or romantic characters frequently appear to be guilty in the middle of the story but are invariably shown to be innocent when the detective finally unveils the solution…

Thus the hard-boiled criminal plays a complex and ambiguous role while the classical villain remains an object of pursuit hiding behind a screen of mysterious clues until the detective finally reveals his identity. The hard-boiled villain is frequently disguised as a friend or lover, adding to the crimes an attempted betrayal of the detective’s loyalty and love; when revealed, this treachery becomes the climax of that pattern of threat and temptation noted earlier. To support this pattern of threatened betrayal, the hard-boiled criminal is often characterized as particularly vicious, perverse, or depraved, and, in a striking number of instances as a woman of unusual sexual attractiveness. Facing such a criminal, the detective’s role changes from classical ratiocination to self-protection against the various threats, temptations, and betrayals posed by the criminal….

Chandler’s characterization suggests that though the hard-boiled detective’s world bears some resemblance to the bitter, godless universe of writers like Crane, Dreiser, and Hemingway, his personal qualities also bear more than a little resemblance to the chivalrous knights of Sir Walter Scott. Not above seducing, beating, and even, on occasion, shooting members of the opposite sex, he saves this treatment for those who have gone bad. Toward good girls his attitude is as chaste as a Victorian father. The very thought of anyone touching his virginal secretary Velda reduces Mike Hammer to a gibbering homicidal maniac. Such knightly attitudes determine much of the hard-boiled detective’s behavior: he is an instinctive protector of the weak, a defender of the innocent, an avenger of the wronged, the one loyal, honest, truly moral man in a corrupt and ambiguous world.

—————————–

Emphasis added; from http://faculty.washington.edu/cbehler/teaching/coursenotes/hardboiled.html

I like (sarcasm alert!) how Coates asserts how Chandler is “mysogynistic” because “Marlowe is forever slapping some woman, or seducing somebody’s wife within minutes of meeting her, or declaring his sexual invulnerability to still another woman,” and utterly leaving out the context; making it seem how the detective goes around slapping women as a general rule. In the Oscar Wilde “Women are like gongs..they should be struck regularly” formulation.

Meantime, where is the hue and cry about males — including the ‘tec — getting brutally beaten, shot, stabbed? “Oh, but that’s different…”

I recall when Helen Reddy’s “I Am Woman” came out ( http://www.lyricstime.com/helen-reddy-i-am-woman-lyrics.html ), whose

Oh, I am woman

I am invincible

I am strong

message was followed by the hit, “Ain’t No Way to Treat a Lady.”

So women are free to be assertive, even aggressive…

http://www.antiquetrader.com/wp-content/uploads/at0804-vice_squad_detective_pulp.jpg

http://robertarood.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/big-book-of-black-mask-stories.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c0/DetectiveBook_pulp_v5n10.jpg/220px-DetectiveBook_pulp_v5n10.jpg

http://www.pulpcards.com/largeimg/pc-057.jpg

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_xPm1kJU3TVc/TBkG9XdYOnI/AAAAAAAArc4/oZb5TerZUm8/s1600/Heritage+of+Hate_Jul+1949.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/_Rs53-MPsJaI/SUwD72zB4MI/AAAAAAAAKzA/YFJX-NgkpDc/s400/blackmask194009+covers3.jpg

http://www.pulpinternational.com/images/postimg/staring_down_the_barrel_06.jpg

http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-HIE15KQWOdg/UJXkFpG5RYI/AAAAAAAAD-I/BYmZ1Lpb6YQ/s1600/crack_detective_stories_194403.jpg (Um, that magazine title is unfortunate…)

http://www.pulpinternational.com/images/postimg/female_trouble_01.jpg

http://pulpcovers.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/lf_-_copy_4-scaled1000.jpg

http://pulpcovers.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/popular_library_337_-_ace_in_the_hole-scaled1000.jpg

…then if they get slapped in return, feminists screech, “misogyny!”

How about considering that a changing attitude towards women — no longer seen as helpless “frails” — was reflected in their no longer being viewed and treated with Victorian genteelness?

I think there’s some truth in that last question, Mike. Also, most of the men die in The Big Sleep, but I don’t believe any of the women do. (I’m sure the counter-interpretation would be that the men who die are enthralled or manipulated by women or femininity, thus misogyny. However, why are the most feminine, namely the women, remaining? Maybe Chandler hated metaphorical women.)

Noah, I’m not bothered, so don’t worry about me (unless you meant that you were becoming too heated, in which case, sorry, didn’t think I was going too far — which applies to this post, too). But I don’t see us getting much of anywhere. I was pleased to see you use the word ‘sexism’, even if it misrepresented our disagreement. I never denied sexism in Chandler’s stories. He’s writing about a sexist milieu, during sexist times, so there’s going to be sexism. You didn’t use that word, though, did you? You said his writing demonstrates and obvious hated of women — that’s what I was disagreeing with. That, of course, would be something other than a matter of his time, would go beyond the typical view of women, become something more significant and heinous. And, again, there are NO quotes used by Coates that demonstrate his and your thesis (misogyny, not sexism), so no wonder your heart’s not in to citing such evidence.

And what’s so incoherent about bringing up the femme fatale here? Chandler writes them; they, too, come from the same time; and, you’re equally reductive about them. Fear and hate aren’t the same thing, nor does one entail the other. Words like ‘homophobia’ really confuse people on this. I’ve hated a few people in my life without fearing them in the least (it’s really easy to separate these two emotions). Conversely, I might love snakes, but still fear them (and for good reason). Thus, there’s definitely something to an expression of fear in the femme fatale, but there’s also an extreme attraction to her. This isn’t hatred. She provided an opportunity to show women with power, agency, and sometimes the ability to play the villain. And she was very feminine. All of this within a sexist milieu. (And, I’ll add, that representing some attitude in a book isn’t the same as advocating for that attitude. I prefer a world where the authors don’t have to give us a list of what they support and don’t support about their characters’ beliefs and the worlds they inhabit.) I imagine you’d call the Thin Man misogynist, too, even though it has one of the strongest women in hardboiled fiction, just because it’s still rooted in some sexist assumptions. Sticking something like parthenogenesis-believing feminist in the middle of these stories who triumphs over Marlowe would maybe get you to stop using ‘misogynist’, but it would be such a white-washing of hardboiled fiction.

And my defense of Chandler or Hitchcock has nothing to do with making either safe for my admiration. I love actual misogynist art, sprinkle misogyny on my cereal in the morning, so sexist art doesn’t go beyond my boundaries. The continual conflation for cheap rhetorical points gets to me, though. It’s dismissive, regardless of whether you like Chandler or any of your other misogynists of the week. If Coates or you had simply said that there’s sexism in Chandler’s novels, I would’ve replied, “duh.”

As for some of your particular plot questions, like Marlowe’s relation to the old man, I remember that feeling like possible manipulation, not a friendship. But I’d really have to read the thing again for that, since it’s been about 10 years. It should come as no surprise that identity politics isn’t what grabs me in these books.

I didn’t really intend to get into an prolonged debate on this, so I’ll let that be my last word.

The relationship with the old man is definitely not manipulation. It’s the strongest and most idealized relationship in the book. Chandler goes out of his way to emphasize the connection between Marlowe and the old man. Male-male bonds are really important in the book. I talk about that here.

I didn’t say hatred and fear and love have to go together. They often do in misogyny, though, and particularly in the femme fatale, and even more particularly in this book.

I don’t actually see misogyny in the thin man films. Those are really different than the Big Sleep, though.

I’m not using misogyny casually or dismissively. The novel is powered by disgust, and disgust and corruption are insistently associated with femininity. The most powerful image of the book is the mad Sternwood daughter, a vision of sexualized, feminized chaos from which the male soldiers recoil.

Again, the argument that men are killed and men are bad seems to really pretty much completely miss the point. Masculinity is absolutely an incredibly important issue in the novel — who is a man, who isn’t, what honorable men are like, how men keep themselves pure. You and Mike seem to have this idea that there you figure out misogyny by looking at the relative fates of the men and women in the book. But that’s silliness. The issue is that femininity is a corrupting influence — which affects men too. As Coates says, masculinity is built on a rejection of weakness which is nonetheless central to masculinity. Even the male body becomes feminized, because all bodies are feminized (so that, for example, the old man’s decadence, with all the hothouse flowers, is thematically linked to the way he’s living with his two united daughters…even old age becomes feminine.)

Misogyny is absolutely an ideology/passion which destroys men, and indeed promotes hatred of men (whether homosexuals, or the elderly, or anyone who doesn’t measure up to being a man, which is everyone.) One of the great things about Chandler’s novel is the way it demonstrates this so clearly and with such passion. It’s uncomfortable and probably evil, but the way it works through the permutations, and the vividness of its loathing for women and ultimately for itself, is fascinating and I think valuable. I like the Thin Man quite a bit, strong female character and lack of misogyny and all, but it doesn’t have anything like that insight or passion.

I think in part the issue is that you and Mike are only seeing misogyny as applying to female bodies? Misogyny is very frequently directed at female bodies…but it’s also, and very much, directed at femininity, which can be associated with female bodies, but which is also a trope which can be seen everywhere, in female bodies, male bodies, or decadence generally. The Big Sleep is actually a perfect example of how this works; the misogyny pervades the entire book, creating a world of corruption, decadence, perversion, and disorder, within which honorable men struggle for cleanness and honor and masculinity.

No personal opinions to add, but I remember Peter Straub saying he was annoyed that his friend and fellow writer Kelly Link called Chandler “misogynist”, apparently she didnt explain.

———————

Charles Reece says:

…I never denied sexism in Chandler’s stories. He’s writing about a sexist milieu, during sexist times, so there’s going to be sexism. You didn’t use that word, though, did you? You said his writing demonstrates and obvious hated of women — that’s what I was disagreeing with.

——————–

Same here! But, it would be reasonable to call it “sexism”…

The thing is, in order to maintain the proper level of frothing frenzy among True Believers, the heinousness of the Other must constantly be ramped up. It’s not enough that there’s plenty of atrocious discrimination against and abuse of women going on, that rape is epidemic in the military; when Connery’s Bond forces Pussy Galore to kiss him, that’s repeatedly called rape; Alan Moore’s work must be slammed as ragingly misogynistic; “nice guys” are all considered closet woman-haters…

——————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

The relationship with the old man is definitely not manipulation. It’s the strongest and most idealized relationship in the book. Chandler goes out of his way to emphasize the connection between Marlowe and the old man. Male-male bonds are really important in the book…

I’m not using misogyny casually or dismissively. The novel is powered by disgust, and disgust and corruption are insistently associated with femininity…

———————–

Why, that reminds of an exchange, from this thread: https://hoodedutilitarian.com/2012/09/spirou-and-fantasio-racism-for-kids/

=================

——————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

I just read this by Ralph Ellison and thought it was maybe apropos..not least because I’m pretty sure Ellison didn’t read Spirou and Fantasio either.

One of the most insidious crimes occurring in this democracy is that of designating another, politically weaker, less socially acceptable, people as the receptacle for one’s own self-disgust, for one’s own infantile rebellion, for one’s own fears of, and retreats from, reality. It is the crime of reducing the humanity of others to that of a mere convenience, a counter in a banal game which involves no apparent risk to ourselves.

——————-

Sure, but “in this democracy”? How about throughout the entire history of the human race, with women getting “the dirty end of the stick” since the Garden of Eden?

By taking an atrocious universal of human behavior and targeting “this democracy,” Ellison makes it appear there’s something uniquely awful about America (or wherever he was living; Rome, perhaps), instead of routinely awful; par for the sorry-ass course.

As to why women being victimized escaped his attention, I wonder if…ah!

In “American Racism and the Legacy of Slavery: Ralph Ellison’s Struggle to ‘Tell It Like It Is’,” we read, starting in page 11:

———————

Ellison always characterizes women in an overwhelmingly negative fashion…

Ellison goes out of his way to characterize women as sexual predators or monsters…Ellison’s misogyny is even seen in the smallest details of the text. As Ellison moves through a crowd, he “became aware of the strangely sinister, high-frequency swishing of women’s skirts.” It is striking that he characterizes anything he associates with females as menacing, even a sound. In addition to Ellison’s commitment to portraying all females in a negative light, masculinity permeates every feature of the essay…

Ellison’s portrayal of his mother continues this trend of disrespect towards women. Ellison only mentions his mother in one scene in the dream even though she raised him as a single mother. Even though his father was not there to help his mother, Ellison still credits his father for giving his mother all of her strength. Ellison does not speak to any extra personal struggles his mother had to endure while raising two young boys on her own after her husband died. Instead, he criticizes her for mishandling his father’s death.

…Male figures and male relationships dominate all aspects of the essay; female figures are criticized, and female relationships are devalued. As discussed earlier, Ellison defines the black experience by equating it to his search for manhood. In doing so, he portrays the black experience as entirely masculine and entirely omits the experience of half of the African American population.

Ironically, by marginalizing the female experience in his narrative of American race relations, Ellison accurately represents a historical truth about the magnitude of discrimination against black women. Black women even endured discrimination within the black community where they struggled for agency. Black women were routinely denied leadership roles within the black community; this even held true for political movements they contributed to like the Civil Rights Movement. The exclusion of women cannot be dismissed as a mistake or coincidence; there were competent female activists ready and willing to donate their efforts to the movement. Black female interests were routinely excluded from political discussions within the black community and the broader American polity.

Rosa Parks famously refused to give up her spot on a bus and she was subsequently claimed as a representative of the civil rights cause. However, a recently discovered essay written by Rosa Parks brings to light that Parks was actually first and foremost an anti-rape activist, not an anti-segregation activist…

———————-

http://tinyurl.com/d3bzvwp

Funny how those who find racism such an outrageous wrong — make a career of it, in fact, as Ellison did — have no trouble with keeping women “in their place,” or worse…

===================

Naturally, faced with massively blatant misogyny by an admired “moral leader” of a Group That Must Not Be Criticized — “The racism made them do it!” — we get not a single word in response.

But, it’s always open season on white hetero Christian males!

————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

Again, the argument that men are killed and men are bad seems to really pretty much completely miss the point.

————————–

Predictably that gets brushed aside as irrelevant. “Yeah, bunches of men get beat up and killed; so what? Now, if a woman gets slapped, that’s outrageous! Blatant misogyny!”

—————————

You and Mike seem to have this idea that there you figure out misogyny by looking at the relative fates of the men and women in the book. But that’s silliness.

—————————-

“V for Vendetta” and “Watchmen” have been raked over the coals as “misogynistic” by feminists (and at length here at HU), explicitly because of what happened or is thought to have happened to women in those books.

…I guess it’s not “silliness” when feminists do it?

One more time; it’s not about condemning the Big Sleep. It’s a reading of the novel which is attentive to how Chandler thinks about gender, and how he connects those thoughts to decadence and corruption.

Also…saying “it’s of the time” tells us nothing. Some people at that time were sexist. Some people were not (or were much less so.) Virginia Woolf was around before Chandler, to name just one relevant writer. I don’t need to condemn Chandler for his views (he’s dead and doesn’t care, after all) but insisting that it is out of bounds to discuss how this writer obsessed with gender relations, masculinity, and femininity thought about those issues, or that you can understand his take on those issues fully just by waving generally at a supposedly benighted past, seems willfully obtuse. The point in talking about Chandler’s sexism is not that we’re better than him. It’s that *we’re not*. The way he manipulates misogyny, and the way misogyny manipulates him, is really, really relevant to how misogyny works today. That’s part of the reason he’s still an interesting writer.

———————–

…Ms. Freeman, a novelist who has lived in Los Angeles, desperately needed to work through her Chandler obsession, especially his relationship with the mysterious Cissy. Their secluded, nomadic life held the key, she came to believe, to Chandler’s work and his most famous creation, Marlowe, “with whom he shared a very particular kind of loneliness as well as a sense of sexual anxiety and a code of honor.”

…The enigma at the center of the books is Cissy. Chandler had the letters between him and her destroyed, leaving scant evidence for a portrait of his wife, who made a point of falsifying her biographical details. In 1924 Chandler believed he was marrying a woman eight years older than himself. In fact, Cissy, a former artist’s model and exquisite beauty, was 18 years older, a difference that became evident as her health declined at a seemingly early age.

Deprived of documentation, Ms. Freeman speculates, often insightfully. Cissy, a powerful sexual presence, mesmerized Chandler. Her age only added to the attraction. Chandler lived with his mother, whom he had cared for ever since his father deserted her early in the marriage. The idea of the knight errant rescuing a damsel in distress, a constant theme in his fiction, worked on his imagination powerfully.

“It was Ray’s job to take care of a needy, vulnerable woman, and it was a job he would embrace, one that would absorb him for life,” Ms. Freeman writes.

The job took its toll. In his 40s, Chandler went on a tear, drinking heavily, indulging in mad affairs and more or less forcing his employers to fire him from his well-paid position as an accountant at an oil company. An avid reader of pulp fiction, he turned his hand to writing, and in Marlowe created “a hero who was effectively beyond the reach of women yet constantly under their spell.” In six of his seven novels, women commit murders.

Ms. Freeman likes Cissy, despite the picture she paints of a deceptive, manipulative, affected woman — she pronounced her married name CHOND-lah — who spotted Chandler’s weaknesses and pounced on them.

——————–

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/12/books/12grimes.html

For sure, Chandler’s attitudes toward women are ambivalent; but hardly the simplistic, grotesque, sweeping woman-hating “Mr. A-thinking” feminists are smearing him with.

(“The idea of the knight errant rescuing a damsel in distress, a constant theme in his fiction…”; arguably sexism, but hardly misogyny.)

A Chandler bio: http://www.detnovel.com/Chandler.html

“One more time; it’s not about condemning the Big Sleep.”

But you’ve pretty much said that its real, or only, value is in its immorality (it’s misogyny and homophobia and whatever other problem it supposedly exhibits). That’s appreciation as a sociological diagnosis. It is condemning the book as a book (which, I say, enjoy it however you want, but you’re being a bit disingenuous). That’s why it’s a dismissive reading. If you ever found yourself believing that the ills it demonstrates were cured, the book would be left useless.

So what…a book is only truly appreciated if you say it offers timeless insights into the human condition? Or what?

I guess I’d be more impressed with your argument if you’d managed to offer an alternate reading which was equally, or, hell, even marginally interesting. All I’ve got from you as far as I can tell is some vague assertions about corruption and violence. “People are immoral and untrustworthy.” Yeah, well, that’s really superinsightful, thanks.

I don’t think it’s a great book. But its loathing gives it vividness and power, and its insight into gender has remained relevant for decades, and is likely to remain so, since the feminist utopia is not around the corner as far as I can see. I don’t see misogyny as any less worthy a topic than some sort of generalized whining about corruption, especially since in practice the two often aren’t especially separable.

What it comes down to is an assertion on your part that if I don’t like the book the way you do, then I’m not sufficiently reverent. To which I can only reply, whatever.

It’s funny that I’m usually taken to task for using more established literature to point out flaws in comics. Here I’ve done the opposite…and the result is that no one even notices, as far as I can tell. I think Johnny Ryan’s take on gender is a really interesting way to put pressure on Marlowe’s…but the reaction is basically just, “how can you be mean to Raymond Chandler like that!” No one even wants to talk about Ryan at all. I guess that’s the way it goes….

I would have to read the book again to give an extensive interpretation. That wasn’t really my point here at all, only that I disagreed with the reductions being proffered. That’s why I said I didn’t mean to get into a big argument over it. I do plan on rereading the Marlowe books sometime in the near future (but only after I plow through a bunch of David Goodis’ stories). Anyway, everything you say here pretty much goes along with what I was calling your dismissal. You don’t really disagree with me on that, I think. Yeah, you’re not much of a fan of the book, and it you really only like it as a representative of your own ideological bêtes noires. Again, that doesn’t bother me, and it’s ok to appreciate a work for that reason. I was only disagreeing on whether the book actually exemplified one of your issues.

Ryan is lame, and I just can’t give a shit about his work. Sorry, man.

Yeah; like I said, I like Chandler’s prose, but his characters are mostly shallow and the morality is simplistic. I can’t love it.

Whereas I find Johnny’s work really inspiring and creative and weird and surprising and funny. But different strokes….

———————-

Charles Reece says:

[Noah] “One more time; it’s not about condemning the Big Sleep.”

But you’ve pretty much said that its real, or only, value is in its immorality (it’s misogyny and homophobia and whatever other problem it supposedly exhibits). That’s appreciation as a sociological diagnosis. It is condemning the book as a book (which, I say, enjoy it however you want, but you’re being a bit disingenuous). That’s why it’s a dismissive reading. If you ever found yourself believing that the ills it demonstrates were cured, the book would be left useless.

———————-

———————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

So what…a book is only truly appreciated if you say it offers timeless insights into the human condition? Or what?

———————–

(Squints at Charles’ post; rereads it again and again) Funny, I can’t see where he’s ” say[ing] it offers timeless insights into the human condition.”

Ah, the classic “accuse somebody of making some outrageous/absurd statement which they in fact did not make, then attack them for making an outrageous/absurd statement” tactic!

For that matter:

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

One more time; it’s not about condemning the Big Sleep.

————————

Ah, the classic “accuse somebody of making some outrageous/absurd statement which they in fact did not make, then attack them for making an outrageous/absurd statement” tactic!

(Yes, this is such a frequent tactic that I’ve recently made a file named “HU accuse” so I can easily find and copy-and-paste that diagnosis.)

Who here was taking issue with you for “dissing” the book? What Charles and I took issue with was Coates and you calling Chandler and his work “misogynist”; simplistically seeing the book as a woman-hater’s fever dream.

I like that “one more time” bit; making it seem like we dumbasses — who just don’t get it; who have to be clued in that “You do realize that the book is fiction, right? The women in it are not real?” — keep getting huffy about the sacred Chandler’s great literary masterpieces being attacked.

When nothing of the sort is going on; in fact, I personally don’t much care for the lunk-headed hard-boiled genre, with the tougher-than-tough hero getting hit over the head repeatedly, punching and bulling his way to a solution rather than using his brain.

I’d rather have “cozies,” please; Hercule Poirot, Jane Marple, Father Brown, that’s my pleasure…

———————–

I guess I’d be more impressed with your argument if you’d managed to offer an alternate reading which was equally, or, hell, even marginally interesting. All I’ve got from you as far as I can tell is some vague assertions about corruption and violence. “People are immoral and untrustworthy.” Yeah, well, that’s really superinsightful, thanks.

————————

I recall when your first comics critique appeared in “The Comics Journal,” and there was an immediate firestorm about how outrageously unfair and inaccurate a slam of a worthy work it was. In your defense, Kim Thompson wrote — as I recall — that he was sick and tired of balanced, fair-minded criticism; that he found an approach like yours more “interesting.”

Well, Fox News is more “interesting” than NPR; and watching it can be “really superinsightful” for studying the way the paranoid world view of right-wingers is constructed.

Personally, boring old nonideologue that I am, I like my arguments and criticism (not to mention view of the world) more “reality-based.”

When challenged to provide some actual evidence…

————————–

Charles Reece says:

Feel free to prove me wrong by quoting one of the quotes Coates uses to prove his case. He asserts his position, that’s all.

————————–

…we get:

—————————-

Noah Berlatsky says:

I’m sorry, I just don’t have the heart to copy the quotes in the linked article to make a perfectly obvious point.

—————————-

Why, G. W. Bush should’ve used this tactic! “I’m sorry, I just don’t have the heart to dig up the evidence that Saddam Hussein had Weapons of Mass Destruction to make the perfectly obvious point that he was a mortal threat to America…”