Lorenzo Mattotti and Jorge Zentner’s The Crackle of the Frost begins with a separation.

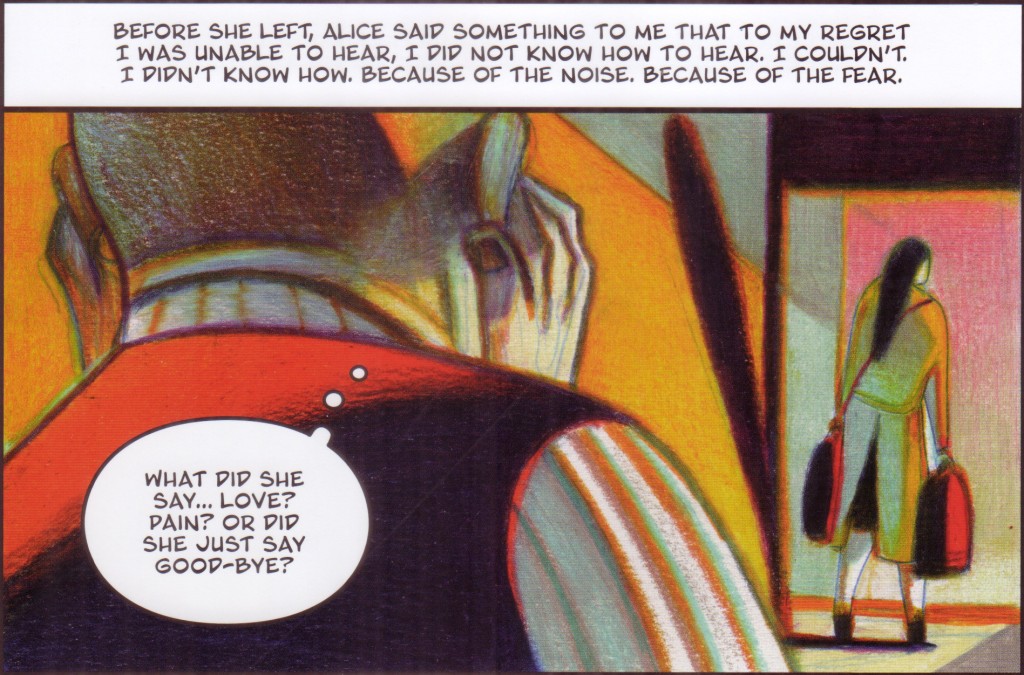

Over the course of three pages, the protagonist, Samuel Darko, recounts the circumstances under which he breaks from his partner, Alice. The disruption occurs the moment she announces that she wants to have a child with him; his seeming lack of commitment or existential terror announced by a flurry of pterosaur-like shadows and a roar in his ears. By the time he regains his senses, she has already left him. Darko receives a letter from her some time later—”mailed from a faraway country”—not quite asking for him, yet somehow enticing him in its self-possession, inspiring him to set out on a extended journey in search for her

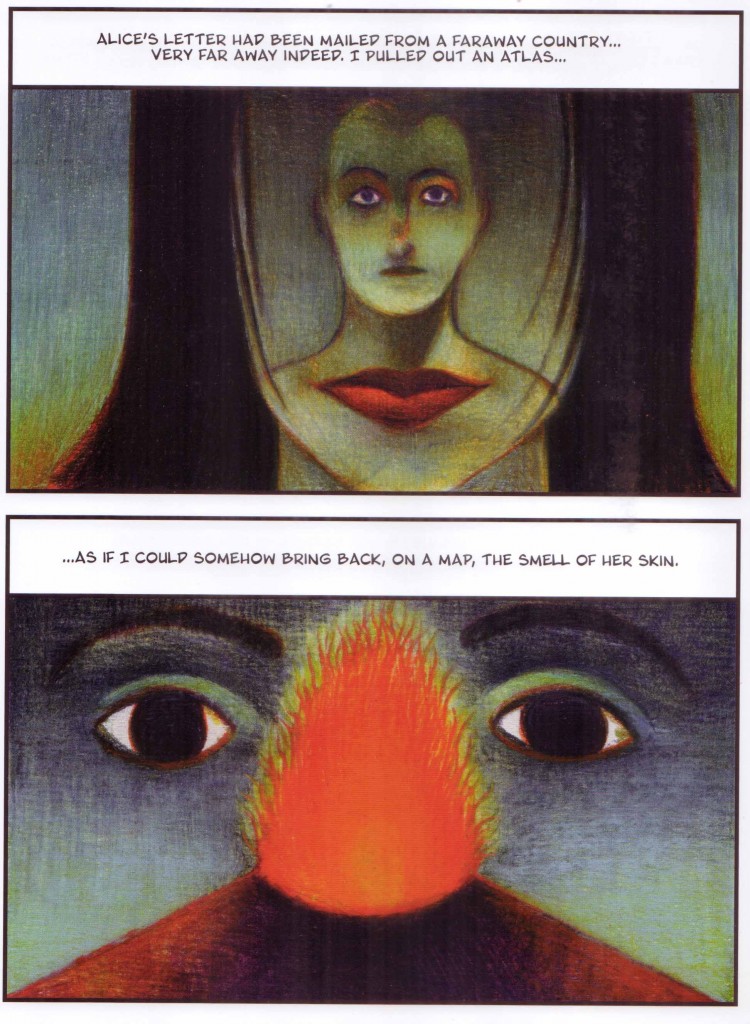

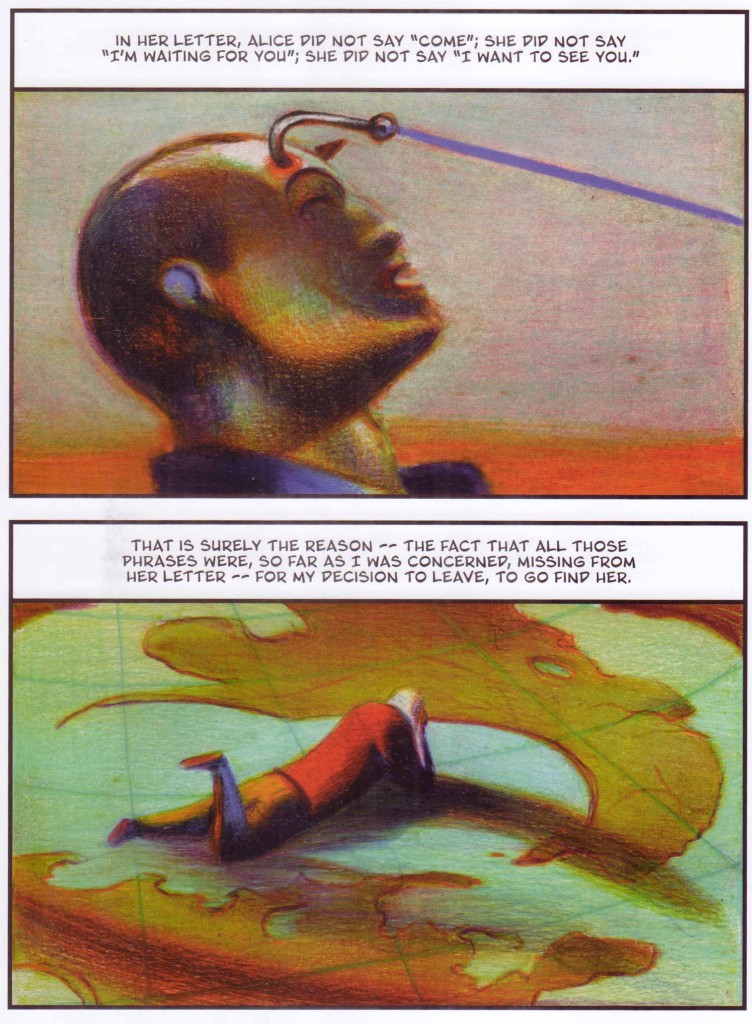

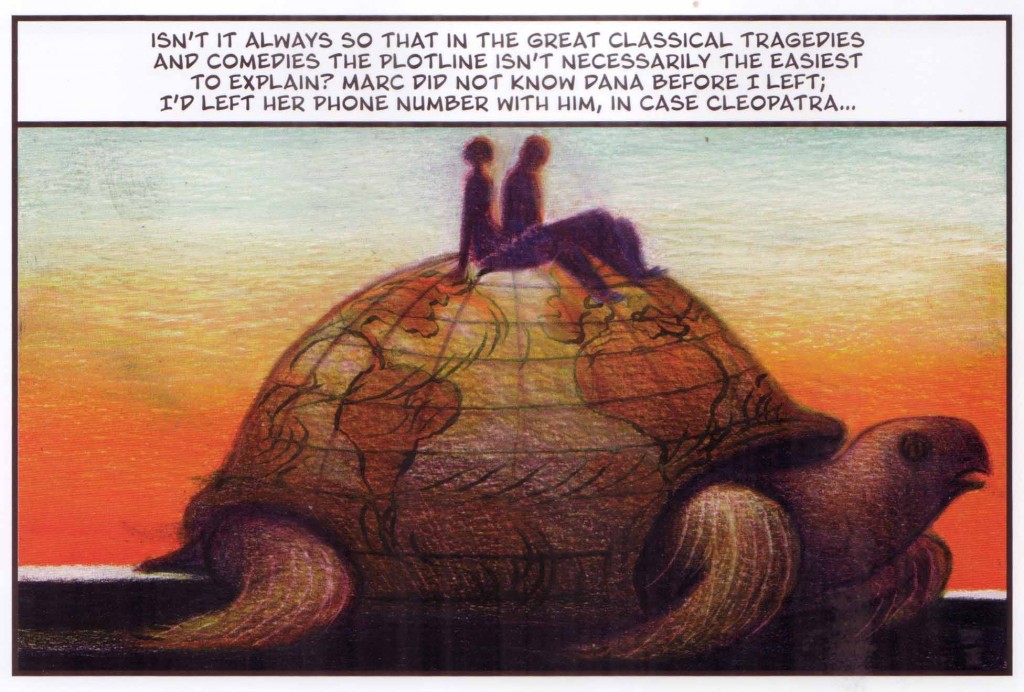

The four panel sequence which relates this decision is a strange union of image and text, not merely illustrating but mystifying the process of description.

__

__

“Alice’s letter had been mailed from a faraway country…very far away indeed. I pulled out an Atlas…”

The “atlas” described in the first panel is displaced to the second panel of the following page with its billowing continents. Instead we see Darko’s face superimposed over his former lover’s nares. The protagonist’s distance from his lover is suggested by a hook of memory, plunged deep into his olfactory bulb (“…if I could somehow bring back, on a map, the smell of her skin.”)

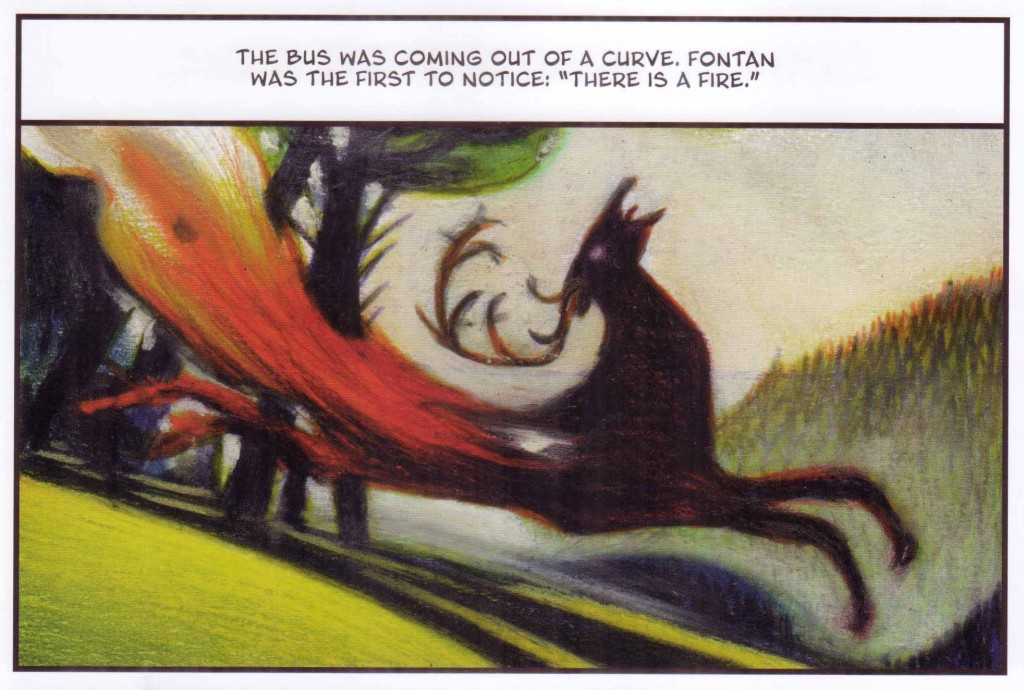

The strange flame scorching through his nostrils in the second panel creates a nebulous map of memory which recurs fitfully throughout the comic. There are the forest animals burnt to cinders on the first leg of his journey…

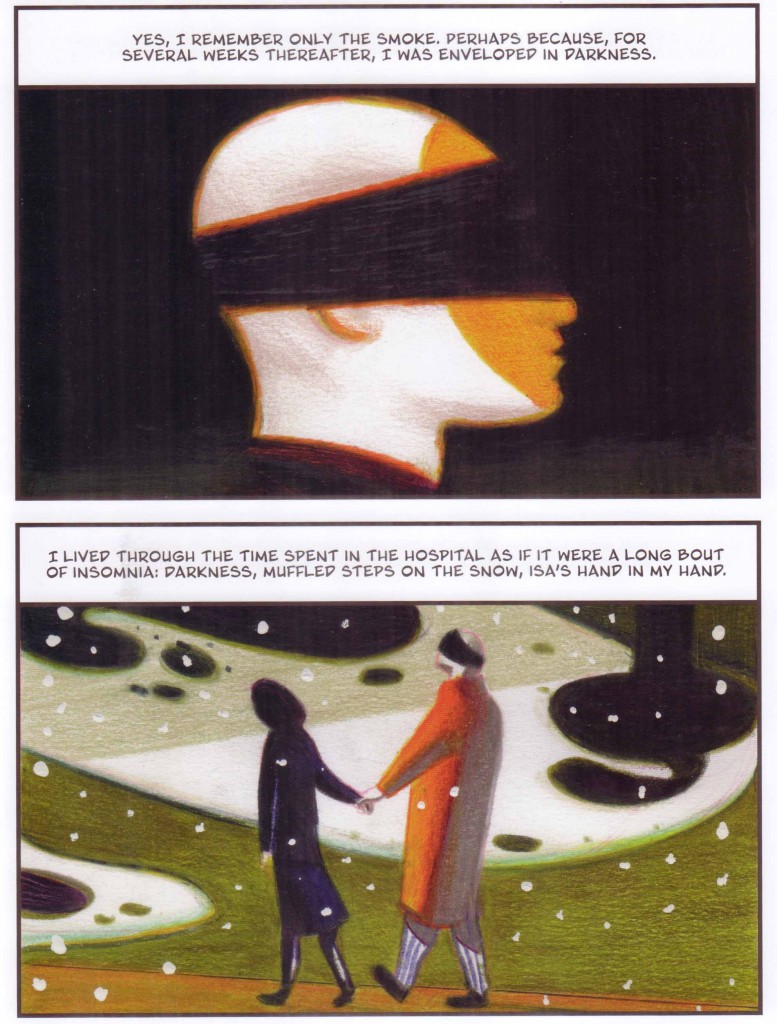

…the black smoke from which soon cast him into darkness, closing his eyes and ears, leaving him with the disembodied hand of his nurse, Isa, and “the mystery of her hand in my hand.”

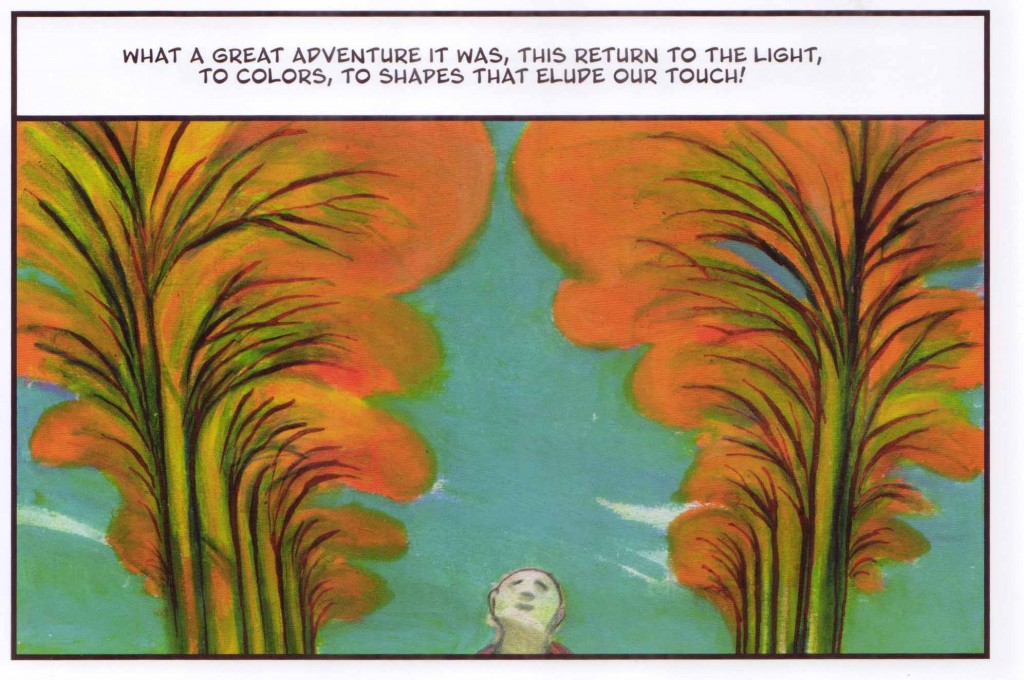

When his mask is removed and he is returned to a world filled with “shapes that elude our touch”, everything is a shade lighter, the shadows cast out by a flood of rhodopsin.

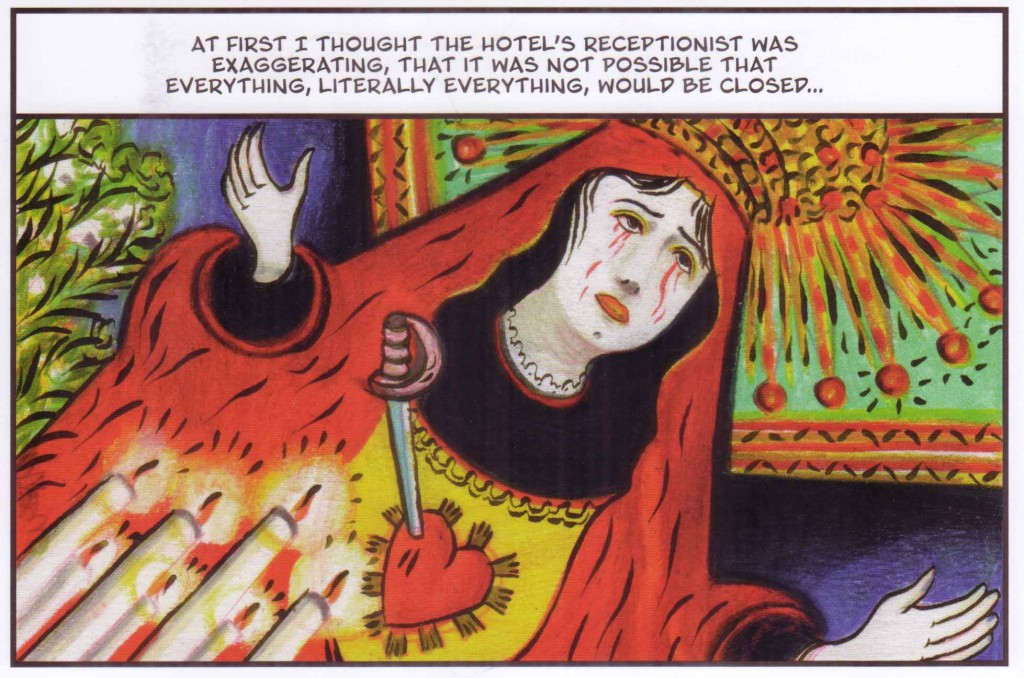

The flame of memory returns again in the form of a Virgin’s crown seen on the night of her festival…

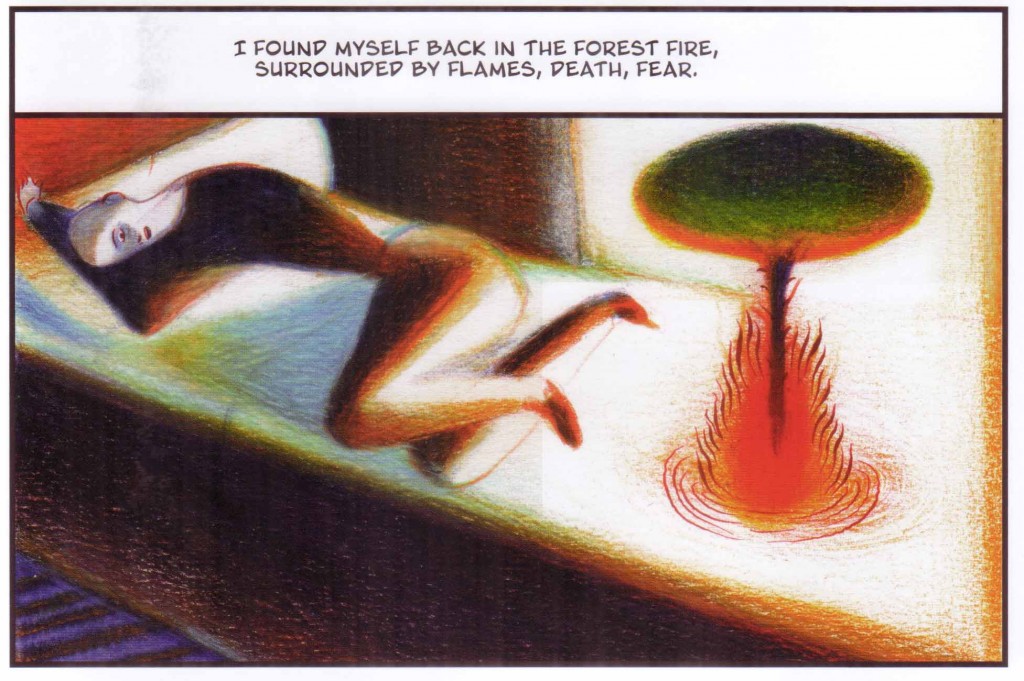

…and then in the involuntary memory of a tree encased in fire—our protagonist’s senses clarified by hunger brought on by that feast day (all the restaurants in town are closed).

The narrative reinforces this symbolism and is interlaced with fables from another time: a Chinese emperor destroying his kingdom to keep it alive in myth and within his “…memory.”

“It alone cannot be vanquished.”

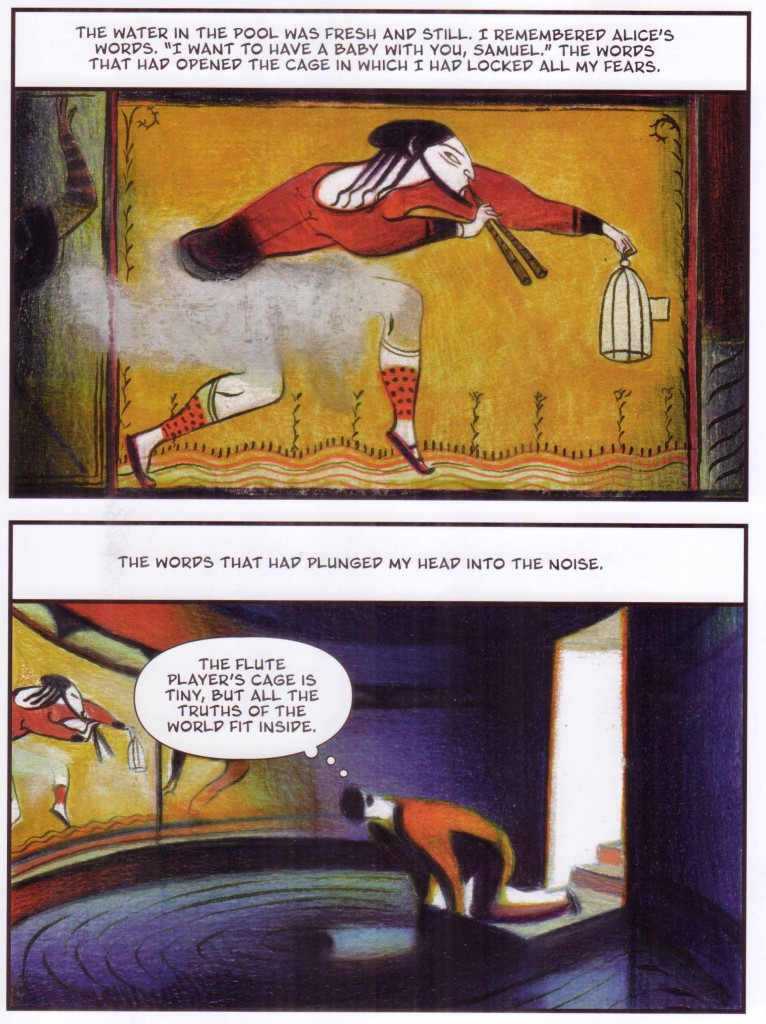

And later, the story of a flute player and his cage which contains “all the truth of the world.” The musician treads gently above the waves of a pool which will cure the protagonist’s eyes forever.

The cage he bears before him so gingerly is a recurrent motif first seen at the start of Mattotti and Zentner’s tale where Darko is told that “loneliness can be a cage within which we keep our fears locked away,” the pastel hues forming lines on his shirt like a prisoner’s dress encasing and straitening him.

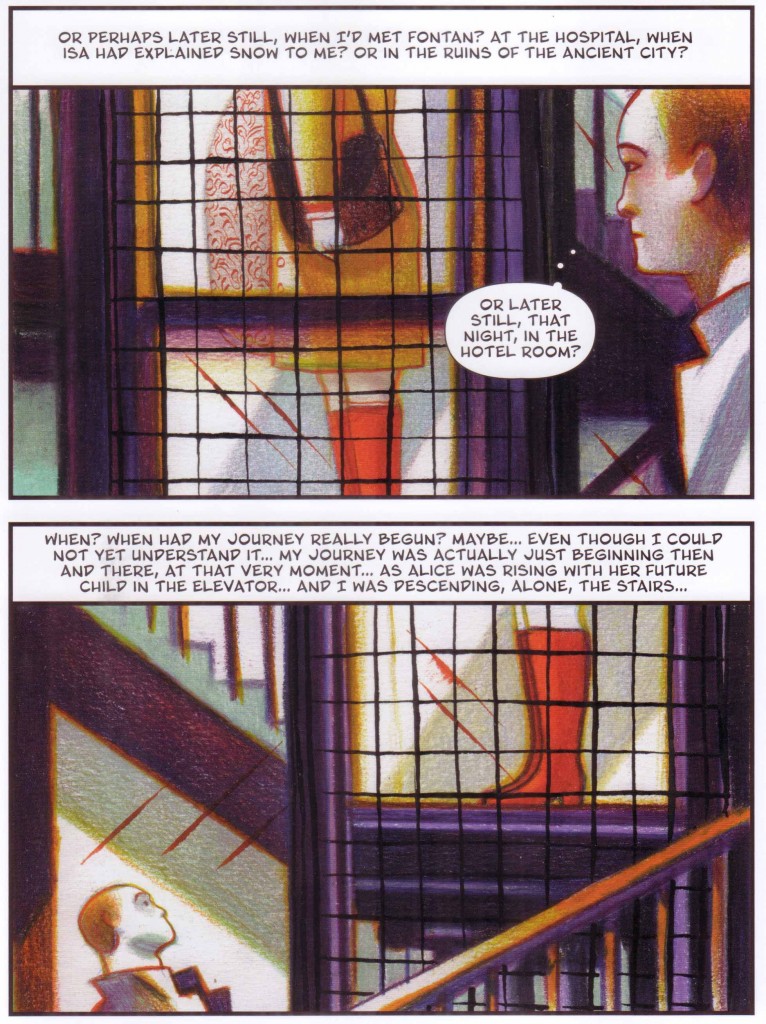

The cage is seen again in the walled city of the aforementioned Chinese emperor, and even further on, superimposing itself on Darko’s pregnant wife who is seen in profile as she ascends in a caged elevator; the protagonist silently wondering to himself just when his journey had begun, his life suffused with a multitude of starting points and hints of irretrievable knowledge.

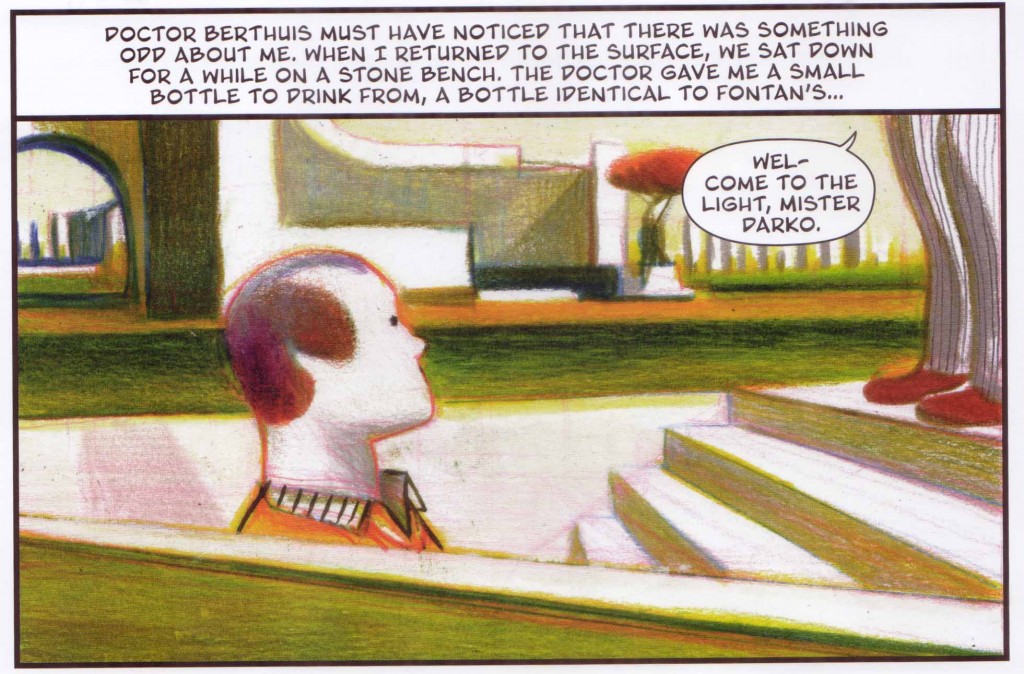

And even if the metaphorical aspects of the comic are announced a bit too brusquely about a third of the way through the book…

“Welcome, to the light, Mister Darko.”

…it can be excused as one of the few times the authors allow a pat explanation seep out.

The scene in question has echoes of Debussy’s (after Maeterlinck) Symbolist opera, Pelléas and Mélisande, in particular Act 3 Scene 2, where Golaud leads Pelléas into the depths of a castle situated in a land of perpetual night, forcing him to glance into a cavern rich with the stench of death.

This before allowing him to emerge on to the ramparts—to the bright sun where “the scent of the wet grass and the roses is drifting up. It must be about noon…”

There is a counterpart to Darko’s impaired vision in the “Blind Men’s Well” described in Act 2 Scene 1 of that opera as well—a place where the stirrings and fate of the doomed lovers are first made plain.

Pelléas: “Since the king is almost blind himself, people don’t come here any longer”

Mélisande: “How solitary it is – there’s not a sound to be heard…I’m going to lie down on the marble. I want to see the bottom of the water.”

The opera consists of dream-like scenes of almost disconnected action, the unifying thread being Debussy’s music; its fellow in the comic being Mattotti’s masterful use of color. And if the an audience wonders whether Maeterlinck’s play concerns love and death, the cycle of creation and destruction, or simply “the presentiment of disaster at the moment of happiness and calm…”

“…the characters in his work do not act; they await action, and if we are not convinced of the certainty of that action, we would be distracted by the resignation.” (Joan Pataky Kosove)

…then the comic reader is allowed to wonder about all these things as well.

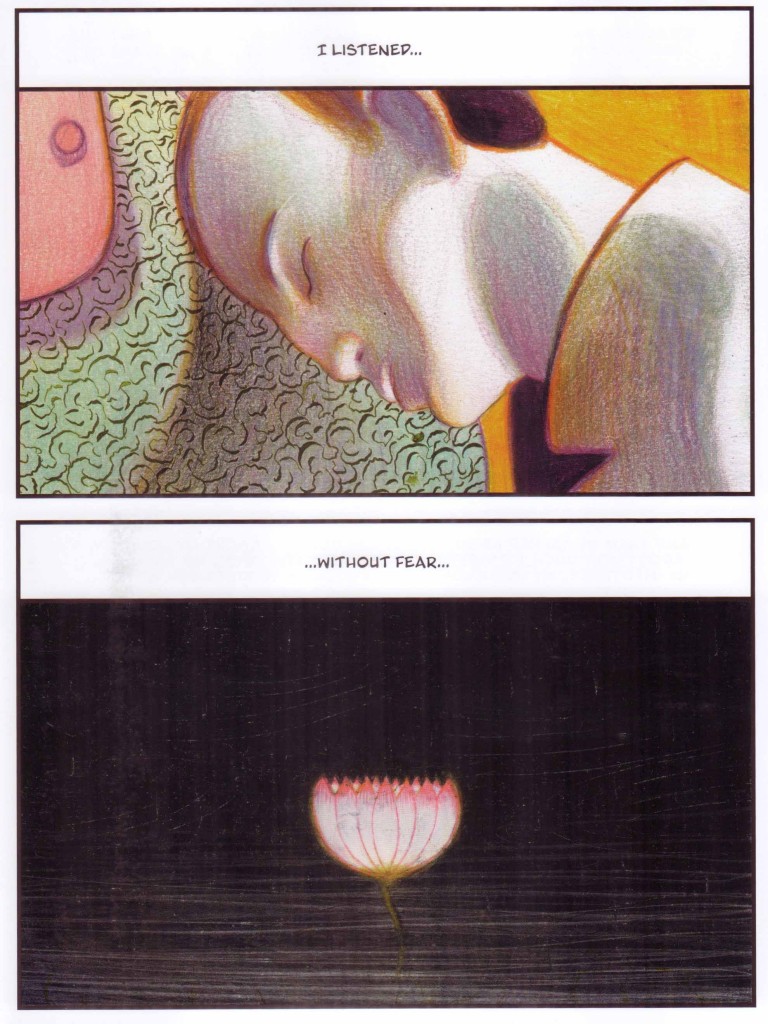

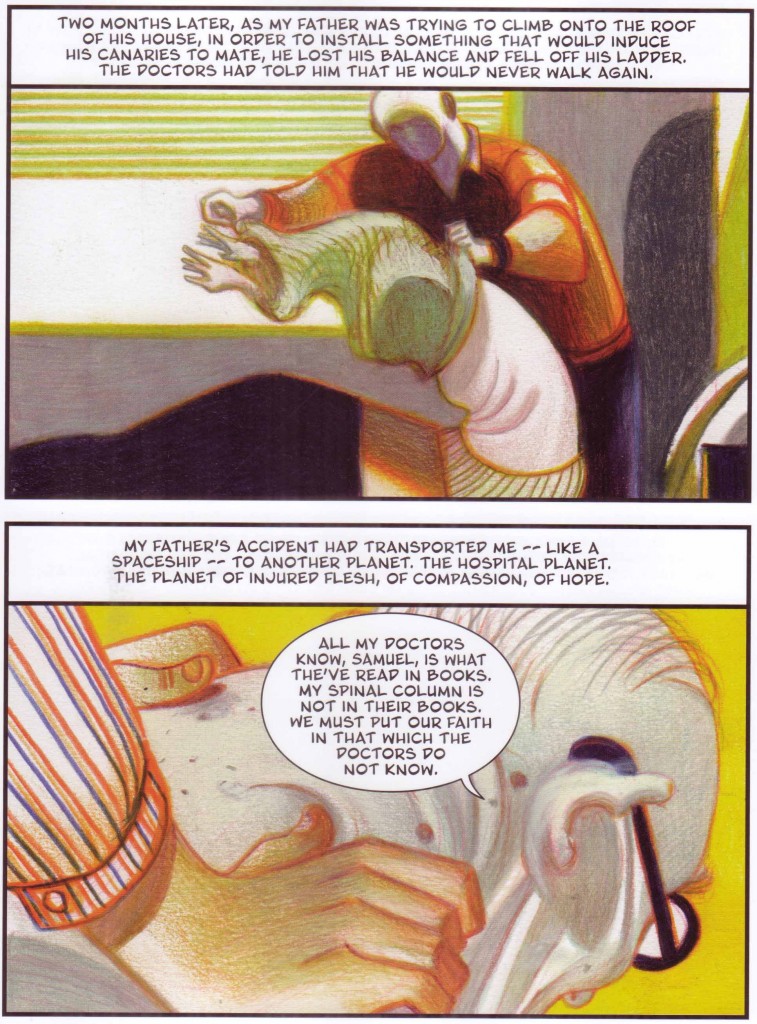

Darko’s fear is banished by an act of creation—a lotus-like flame emerging from the darkness like a Buddhistic totem symbolizing love and compassion. But his journey only ends when he meets another man—his father bent with age and sheathed in the same prisoner’s dress as his son, a reflection of himself; his memories reeled in once again by his sense of smell—of his “father’s nakedness”, his father’s “breathing”.

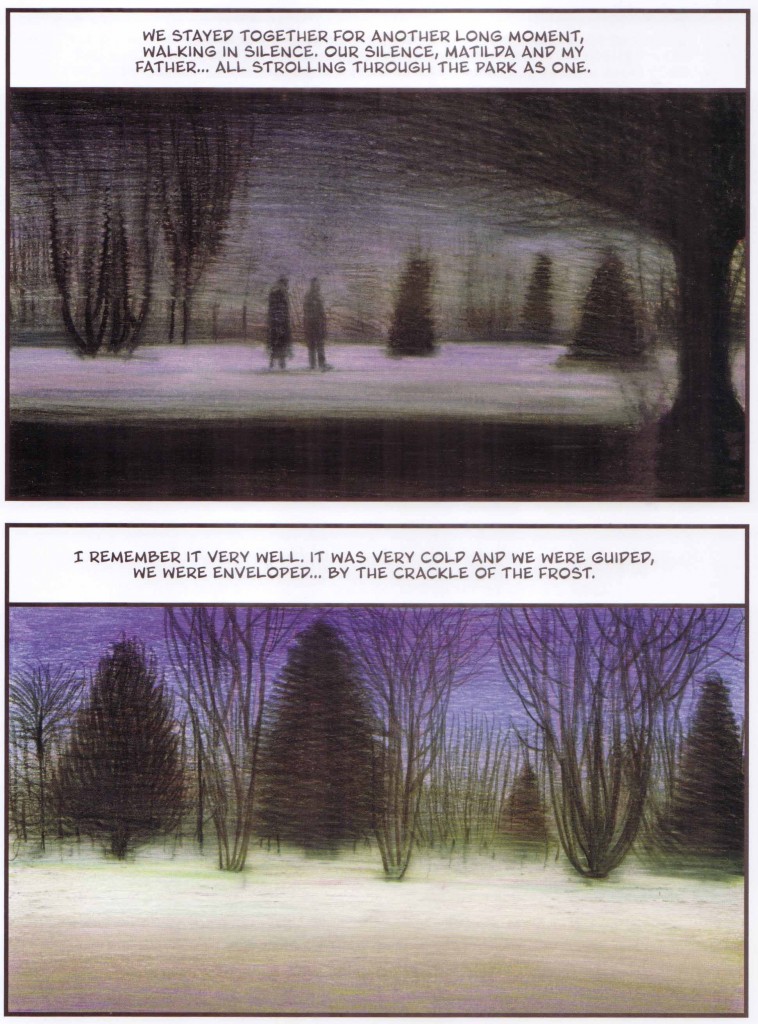

And there it ends, the questions as unanswerable as the mystery of life itself. In the hospital grounds, Darko spots a “bright light in the darkness”—another man “taking [his] worries for a walk among the trees” who can only talk about his as yet unborn daughter, Matlida; the protagonist’s father joining them in his thoughts as they push through the breaking cold in search of intangible yet nascent rest.

Further Reading

Sarah Horrocks with a more traditional review The Crackle of the Frost.

Fascinating review. I read this years ago and remember very little of it, but I do remember preferring it to most other Mattotti, which I’m not crazy about, despite his obvious mastery of a certain expressive spectrum. How does it compare for you, Suat?

Hey Matthias, been away from home with spotty Internet access.

I probably still prefer Fires and Murmur to this one though I have to say I haven’t read either of those in years. Think this one works better than Fantagraphics’ earlier offering of Stigmata though Domingo’s might disagree.

Yup, I prefer Stigmata, but I haven’t read a Mattotti (with some writer) book in ages. If I remember correctly The Crackle of the Frost interested me at the time because of Mattotti’s use of the visual figure of “speech.” I mentioned this briefly in my discussion with Matthias in Oslo.

Yeah, we discussed that a bit, and I guess I agree at least that “Crackle” has a more nuanced visual side, in terms of color, than earlier works, but I am generally more drawn to Mattotti’s black-and-white art. My favorite story of his remains “Il segreto del pensatore”, which was released in English as “Chimerae” in the Ignatz series. Obviously “Stigmata” is beautiful too, but I remember it as a really heavy read, feeling that I had to be better versed in Catholic theology to fully appreciate it. On the balance, I remember “Crackle” as the most succesful in terms of being moving and fairly straightforward without too much dull pretension à la (my recollection of) “Murmur”, “Fires”, and also “L’Homme à la fenetre” for that matter. (Perhaps it is time to reread these books, instead of writing on the basis of vague recollection though…)

Mattotti did a great Hänsel and Gretel.

I think the last sequence in Stigmata, the “religious” sequence, was tremendous. A real tour-de-force.

Oh yeah, those Hansel and Gretel illustrations are impressive — they’re huge too; they had one on display at the CBDI in Angoulême last January. To me, however, Mattotti’s almost ostentatiously elegant flowing line works a little counter to the story’s grim rusticity.