This first appeared on Comixology

______________

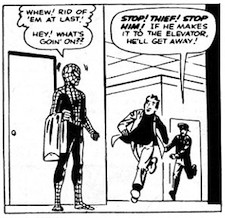

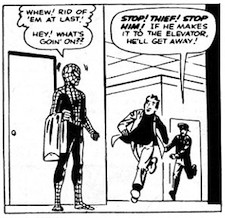

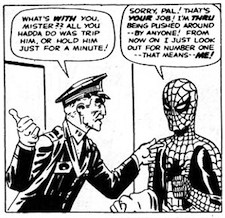

Spider-Man’s origin story, as most everybody knows, hinges on a moment of moral turpitude. In Amazing Fantasy #15 by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, nerdy, put upon Peter Parker, having been bitten by that pesky radioactive spider, gains (dum ta da!) super powers, and starts a successful career as a professional wrestler. Basking in his newfound fame and bucks, Peter (in Spidey costume) is standing in some random corridor when he sees some random schmo fleeing from a cop. Cop yells to Peter to stop schmo, but Peter refuses ; schmo gets onto high-speed elevator and escapes.

Spider-Man’s origin story, as most everybody knows, hinges on a moment of moral turpitude. In Amazing Fantasy #15 by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, nerdy, put upon Peter Parker, having been bitten by that pesky radioactive spider, gains (dum ta da!) super powers, and starts a successful career as a professional wrestler. Basking in his newfound fame and bucks, Peter (in Spidey costume) is standing in some random corridor when he sees some random schmo fleeing from a cop. Cop yells to Peter to stop schmo, but Peter refuses ; schmo gets onto high-speed elevator and escapes.

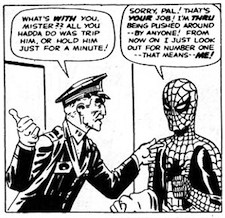

The cop chews Peter out, “All you hadda do was trip him”! Peter, though, is unrepentant: “Sorry, Pal! That’s your job! I’m through being pushed around!” Peter walks off and then on the next page his uncle is murdered! And two pages later, Peter learns that the guy who shot his uncle is the same guy he allowed to escape! Oh, the irony! Peter has learned too late that “with great power there must also come — great responsibility!”

Anyway, back to that moment of moral turpitude. What exactly is Peter’s failure here? The cop says that Peter should have tripped the guy or stopped him somehow. He even threatens to arrest Peter for failing to help. But… arrest him for what? Do citizens really have a legal obligation to throw themselves in the way of fleeing criminals? Do cops even really want citizens to throw themselves in the way of fleeing criminals?

On the contrary, if you’re a cop chasing a perp, the last thing you want is for some civilian in goofy red tights to get in the way. What if the perp has a concealed weapon (and in this case, we know that the villain did have a gun by the next page)? What if the civilian tackles the perp and then gets shot? What if the civilian tackles the perp and somebody else gets shot? At the very, very least, from a police perspective, that’s an exponential increase in paperwork.

Of course, we know that Spidey could have taken down the baddy without anyone getting killed or even hurt. We know this in part because he’s got super powers. Mostly though, we know it because — Duh! — he’s a super-hero, or even just a hero. Heroes like Spider-man or Batman or Dirty Harry leap into action and save people. That’s what they do. And if they didn’t do that, there wouldn’t be much of a story, would there?

Indeed, Spiderman’s real sin here is not against morality or society, but against the tropes that keep the genre afloat. Super-heroes have to act. They’ve got to fight crime. If they don’t, you don’ t have a narrative. Super-heroes have “great responsibility,” but it’s always the responsibility to do something. You could conceivably have an origin story in which Wombat-Man decked a baddy, the gun went off, Cousin Joe got shot, and the hero decided “With great power comes great responsibility!” And so Wombat-Man decides never to mess with crime again, and instead uses his phenomenal digging powers solely to aid with infrastructure projects! Again, you could have such an origin – but what you’d end up with would not exactly be a super-hero comic.

Indeed, Spiderman’s real sin here is not against morality or society, but against the tropes that keep the genre afloat. Super-heroes have to act. They’ve got to fight crime. If they don’t, you don’ t have a narrative. Super-heroes have “great responsibility,” but it’s always the responsibility to do something. You could conceivably have an origin story in which Wombat-Man decked a baddy, the gun went off, Cousin Joe got shot, and the hero decided “With great power comes great responsibility!” And so Wombat-Man decides never to mess with crime again, and instead uses his phenomenal digging powers solely to aid with infrastructure projects! Again, you could have such an origin – but what you’d end up with would not exactly be a super-hero comic.

In real life, of course, and as this suggests, the responsible, way to use your “great power” might conceivably in many circumstances be to sit on your ass and do nothing in particular. Certainly, if George W. Bush had done that in 2003, America and Iraq would both be a good bit better off today.

What I’m talking about here is essentially pacifism. Pacifism is about as massively discredited as a major philosophy can be. Pacifism is appeasement, or it’s treason, or, (more kindly) it’s a nice idea but not really practicable. You can’t just sit by and watch that guy escape, Spidey! Hit him! He’s got weapons of mass destruction!

I can’t say that I’m a pacifist myself, exactly. But I think that people can be way too quick to dismiss it, essentially because reality is rigged just like that Spidey origin story. For whatever reason, probably having to do with our reptile hind-brains and/or a steady consumption of revenge narratives, the negative consequences of inaction tend to seem to us infinitely more insupportable than the negative consequences of action. If we step aside and something bad happens, we say, “Oh no! I should have done more!” On the other hand, if you wade in and things get completely fucked up, you often feel like, “Well, at least I tried. And think how bad it would have been if we’d done nothing!”

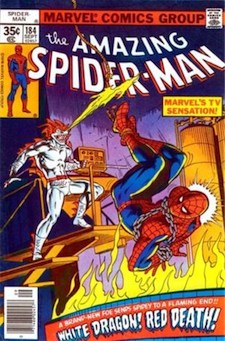

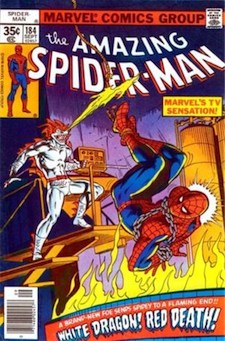

Which brings me to Amazing Spider-Man #184, published way back there in September 1978. My friendly neighborhood Internet tells me this was written by Marv Wolfman and drawn by Ross Andru. I must have read this when I was 8 or so; and I don’t think I even liked it all that much at the time. But I’ve remembered it all this time, in part because it is, rather bizarrely, one of the only super-hero comics I’ve ever seen that makes any effort to address either pacifism or the anti-pacifist assumptions at the core of super-hero comics. (The alternate-world Amish Superman in The Nail does not count. We will not speak of him again.)

Anyway, I haven’t seen ASM#184 in probably twenty years, but if memory (and a Web capsule summary) serves, the plot was a Bruce Lee rip off. Phil Chang is an awesome martial arts master, but he’s taken a vow of non-violence. Inevitably the evil Chinese gang wants him to join them. Their leader is the White Dragon, who is not only a martial artist extraordinaire, but also wears a white (natch) costume with a Chinese dragon style mask that looks staggeringly impractical, even by super-hero costume standards. Despite said mask, though, the Dragon is fully able to beat the tar out of the non-resisting Chang, and so he does – until Spidey comes to the rescue. Thank God someone is willing to fight, huh kiddies?!

That’s what you’d think the message would be anyway. In fact, though, Marv Wolfman’s script is surprisingly subtle. One exchange in particular has really stuck with me. I can’t quote exactly, alas, but to paraphrase, it went something like this:

Spidey: What in tarnation are you doing, anyway? The White Dragon is beating you to a pulp! He’s going to kill your family, you dope! Show me some of that kung-fu everyone’s been on about, won’t you? Are you a man or an amoeba? Come on, Phil! With great power comes great responsibility!

Phil: (and this I remember much better) There are failures in non-violence just as there are failures in violence.

I think that’s pretty profound. Yes, pacifism won’t necessarily solve all your problems. But then, fighting often doesn’t solve your problems either. Indeed, fighting can quite easily make things worse. You wouldn’t know that necessarily from reading super-hero comic books, of course — nor, perhaps, from public discourse in general. Which is why it might be worthwhile, sometimes, to remember that the power to right the world’s wrongs is given to neither man nor spider, and that we are all every bit as responsible for what we do as for what we don’t.

So what is pacifism? It is the uncompromising realization that we as humans are incapable of bringing about justice through violent retaliation. Hence, we relinquish all such acts to God in his sovereign and eschatological plan of judgment, justice, and mercy. Indeed, God have mercy on us.

—Mark Moore