The many faces of Psy in Gangnam Style. You can buy these as stickers. Collect them all!

First of all, here’s the video, if you haven’t seen it already. If you are sick of the song, you can also watch it without music.

Secondly, in my third-most-ever-favorited comment on metafilter, I talked about Psy’s Gangnam Style and race in America:

Gangnam Style isn’t the first viral smash Kpop song, or even the first viral smash Kpop song that sort-of sounds like LMFAO and was produced by Teddy Park of YG Entertainment (who has been working with the artists to adapt the same ultra-mega-popular song into a huge smash hit every six months like clockwork – here’s 2NE1’s I Am The Best and Big Bang’s Fantastic Baby, if you missed them the first time).

But of those three acts – each of which has already gotten a lot of U.S. attention, i.e. Pitchfork wrote about 2NE1, Will.i.am worked with them, MTV Iggy called them the best band in the world; Big Bang were crowned Best Worldwide Act at the MTV Europe VMAs and have been written up in US and European business magazines – Psy, a previous unknown (to the US), is the act the entire Western celebrity world has decided to back.

Psy and Bigbang’s G-Dragon, hanging out.

On metafilter, I speculated that while not precisely a conspiracy, the choice to throw US media and celebrity weight behind Psy and not another act was a tactical move:

Compared to those other songs, “Gangnam Style” is a lot more relatable to the average person – it’s a song about acting like you are rich, whether or not that’s really true, rather than a song about being actually rich and famous (although Psy is both of those things, in South Korea).

More than that, it’s relatable for the average American, who can comfortably put Psy in a couple pre-existing mental boxes: hilarious “not attractive” guys partying hard and getting the girl; funny Asian guys; funny viral videos built around dead-serious funny performances in public places; even subtle social commentary. Bringing Psy over here broadens people’s ideas of a viral pop song a little bit, since it’s in another language, but not too much, since, after all, Psy is singing about how he isn’t the

rich person he dreams of beingtypical celebrity guy.

Psy x Justin Bieber. They share a manager in the US, Scooter Braun.

To expand on that a bit more – and please forgive me for retreading already well-tread ground – Psy’s Gangnam Style video isn’t just funny in ways that Americans recognize, e.g. the hot tub scene borrowed from Austin Powers. It’s also implicitly critical of “all flash no substance” celebrations of celebrity vanity/megalomania.

For instance, here are videos by B.A.P., f(x), Jo Kwon, Tasty, Girls Generation and After School proclaiming their own greatness – although this last one is a Japanese single released by a South Korean group, not properly a Kpop song. It is, however, a great example of the kind of stadium-ready pop South Korea has been making since the World Cup last summer, and again this summer in celebration of the Olympics – for which Psy has, natch, written the official theme song.

Psy performing at one of his famously crazy concerts, underneath (cartoon) images of himself.

The difference between those groups and Psy isn’t precisely hubris as Gangnam Style is, after translation into English, already plenty boastful. Rather, it’s a comment on artificiality: Psy’s video is set in the real world – albeit one full of celebrity cameos and action-movie stunt acting – while other groups save money by filming in constructed worlds made up of empty mansions, empty clubs and empty rooms; or else in the “real” Kpop world of stage lights and dressing rooms. And that’s if there is any nod to reality at all. In its purest form, Kpop features locations that aren’t just abstract and prone to disorienting lighting, but subject to no other logic but the logic of capitalist consumption – a predilection that’s been noted on this blog previously.

Psy live in Australia, in a concert still that looks like an action-movie poster.

Of course, there’s a lot of self-awareness in the artificiality of these videos… in addition to being generally more economical, they sometimes also double, Lady Gaga-like, as commentary on their own artificiality (one, two, three).

Images of Psy proliferating everywhere on the latest episode of South Park.

But to return to the topic at hand: The good-looking teen and twenties celebrities who populate Kpop music videos belong in their world, being in part “constructions” themselves – that is, the groups are definitely constructed; the personas are partially constructed; and the faces and bodies are meticulously constructed through a combination of professional makeup, professionally-guided diet and exercise, and plastic surgery. Psy, although also a nominal member of this set – and actually hailing from the swank Seoul district of Gangnam, Korea’s plastic surgery capital – does not look like he belongs with them, and therefore has to fight to be recognized as belonging to a glittering world in which only handsome people exist.

Speaking of handsome people: Psy with Hugh Jackman

Despite what the Atlantic would have you believe, however, Psy is far from alone in his satirical take-down-from-within-the-industry. Even apart from direct critiques – of superficiality, of sexist double standards, of government censorship, of materialism and gender roles – Gangnam Style actually comes in the middle of a move toward broadening the appeal of Kpop by setting it in real places. Like This and Ice, for instance, are two of this summer’s other attempts, proceeding Psy’s, at LMFAO-style outdoor flashmob videos.

Psy leading an impromptu(?) flashmob on The View

With that said, there’s still plenty of artifice to go around. On metafilter I concluded that trying to viral-market any of the more obviously constructed groups in the US

would require a long explanation about what Kpop is and why those artists “really are” famous. This would require the U.S. public to buy into a world where the U.S. is not the center of all pop music production “that matters”. So yeah, I think there is quite a bit of commercial calculation behind the media push of [Gangnam Style]. Which doesn’t mean it’s not a great song worthy of being spread, just that there is a reason it was

thingthis song, and not some other one.

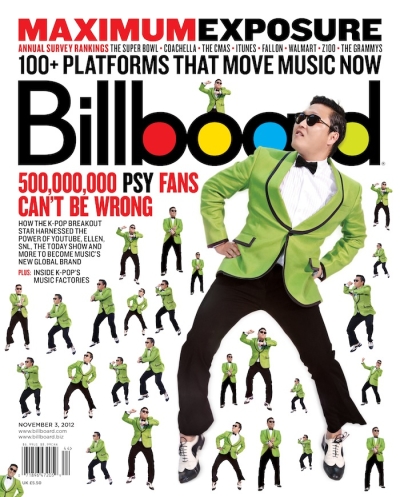

Psy presiding over many images of himself on the latest issue of Billboard

Do I still think this way about Psy’s smash hit? Yes and no. Here’s Ask a Korean, probably the first place you should go for answers to these kinds of questions, on the reasons for the song’s success overseas:

First, Korean pop music has been laying a solid groundwork for PSY to succeed. It is true that, thus far, efforts by Korea’s pop stars to break into the U.S. market resulted in a flop. Top stars like Wonder Girls, Girls’ Generation and 2NE1 never made a dent on America’s public consciousness. Nevertheless, the groundwork that these groups laid remains important. Because Korean pop music at least got on the radar screen of the insider players of American media market, PSY’s music was easily accepted by those insiders.

This is a crucial point that separates Korean pop music and pop music from other, non-Anglophonic countries. Through repeated contacts with American media, Korean pop music had a ready audience among American media insiders.

Check the original post for more, including a great graphic of a T-Pain-centric view of the universe.

Psy with ultimate Hollywood insider Steven Spielberg.

Though initially on the “why this song and not another?” train, I’ve since rethought my position. Maybe it’s true that Gangnam Style doesn’t threaten a US-centric view of the US’s place in the center of world the way that another, more nakedly imperial song would. On the other hand, this song is also popular in Istanbul!

This has been on my mind since I was Turkey recently. Istanbul, at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, has pockets of hyper-capitalism inside a generally conservative culture – kind of similar to Korea? In any case, a gazillion Turkish parodies exist for Gangnam Style, including this one with found footage of old men dancing at weddings. “Uncool” guys acting “crazy” for the benefit of young, conventionally attractive women, whom they would like to impress, is a near-universal phenomenon, it would seem.

Another artist who is popular in Istanbul, Sardor Rahimhon. Lacking Psy’s discipline, he is occasionally photographed out of uniform.

And everyone loves a silly dance craze. This is anecdote, but it’s not just that this song is playing at cafes; from our hotel room in the old city, we saw a guy doing the horse-dance down the street…

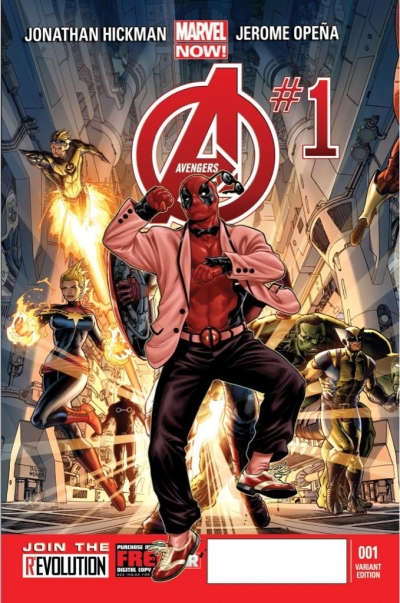

Deadpool doing the Gangnam Style horse dance on the latest issue of The Avengers.

I have kind of come around on Gangnam Style, then, and now think the silly – and yet instantly recognizable – dance on top of the ridiculous – and yet instantly recognizable – LMFAO-style beat is the main thing, along with the boost from American media/celebs who rightly saw the viral potential of the video and performer.

In the final analysis, then, the viral power of Gangnam Style comes from its being instantly recognized, widely liked, and easily reproduced. But where is Psy getting that cool-dorky look from anyway? Technically, from trot: Korea’s traditional pop music form which is currently experiencing something of a revival. Psy only looks trot, though: his music is pure 00s bombastic stadium rock, mixed to already sound like it is being played over loudspeakers at a large sporting event.

But what about that trot beat, eh? Another thing I will throw out for your consideration – if only because I haven’t seen it mentioned elsewhere – is Serbia’s entry in the 2010 Eurovision contest. Op, op, op! Ovo je Balkans! For more on this connection, read on…

Frank Kogan – Koganbot – has been writing about what he calls the Austral-Romanian Empire, a pop music spectrum that ranges from Tu Es Foutu and We No Speak Americano in the East (Australia/Oceania) to D-D-Down and Mr. Saxobeat in the West (Romania). To his list of Kpop singles that incorporate sounds from across the (Eastern) world music spectrum, I’d add Musiche by Crazyno (pronounced Cray-ZEE-no)… a guy dressed up like a Balkan entertainer/a trot performer/Psy…

Crazyno is from Australia! Perfect! But is he willing to wear that suit every day for the rest of his life?

The influence isn’t one-way, of course. Kazakhstan has their own Kpop-style boyband, for instance: Orda, also here. And meanwhile, a Kpop group that’s always had a strong European following is TVXQ, who right now have my current favorite take on the LMFAO Party Rock beat. Even knowing about this connection, however, it took going to Istanbul for me to notice exactly how much like typical Eastern European pop the video for Tallentalegra – by former TVXQ member Xia Junsu – is. You know the kind of thing I’m talking about, right? It’s a look that’s so well known (on women) that it was parodied by Hilary Duff in Iraq War black-comedy War, Inc.

Last celebrity cameo! Psy with Golden Girl Betty White

So there’s that. In other examples of trend-chasing, meanwhile, there’s the micro-trend of British-chart-sounding singles at YG Entertainment (Psy’s company): Dancing on My Own, I Love You, Don’t Hate Me, CraYon. For comparison/contrast, here is UK pop group Girls Aloud.

No corner of the globe is safe, however! If you want to find some Spanish guitar-y singles, you can find them as well: Wow, I Wish. Is Block B going for a similar audience, or a US audience, or in fact a worldwide audience with their Pirates of the Carribbean-sounding single Nallila Mambo (which you absolutely must watch)?

All of this is without even getting into Kpop’s first successful overseas expansion…to Japan. As my friend Sabina said, this is where the Italo producers went after Italodisco died in Europe. 4minute have multiple Japanese singles in this style. When people talk about Kpop, “Gee” and the Norwegian wave, they are generally talking a collaboration between Kpop songwriters and European dance producers. Many words have already been spilled on this particular connection, so I won’t spill any more – check Thomas Troelson’s wikipedia page for a general idea.

So it’s no surprise that Turkey is ready to embrace this pop amalgam, existing, already, at the crossroads of pop. Pop music television in Istanbul is a mishmash: they got stuff from the US and the UK, stuff from Eastern Europe, stuff from Russia, stuff from India…

Okay okay, this is the last celebrity cameo. Psy with Ban Ki Moon, current Secretary-General of the United Nations

Someone called the Kpop style the style of the mashup, but I don’t think that’s quite right. I think there are some unique things that no one else really does, or at least that are not a part of mainstream pop elsewhere. For example, I think that Kpop produced for an older domestic audience follows slightly different trends and is slightly less bombastic – or at least is bombastic in a more complex slash tortured slash melodramatic slash tragic way. But as this post is already a bit long, perhaps I’ll talk about that next time.

To bring this back to Psy, the market is nothing if not adaptable. It didn’t take underground-rapper-with-pop-ambitions E.via very long, for instance, to come out with a response song and video. She’s even using a cartoon image of herself to promote!

And speaking of cartoons, you have been wondering about that Deadpool-doing-the-horse-dance Avengers cover, right? Wonder no more: Deadpool VS Gangnam Style.