Reprinted from The Comics Journal #250 (2003)

“But have you heard anyone say, “Lord! When I was young, we didn’t have such nice games to play!” Or, “When I was little, there weren’t such wonderful story books!” No. Whatever people read or played with in their childhood not only seems in memory to have been the most beautiful and best thing possible; it often, wrongly, seems unique.”

“Children’s Literature”, Walter Benjamin

In 1956, on the imminent demise of EC Comics, Larry Stark, one of the company’s most ebullient young fans wrote a heartfelt elegy for the “best-written comic magazine line ever published” (Hoohah! #6). Amidst enthusiastic descriptions of the EC office and its working practices, Stark managed to provide a fan’s eye analysis of the comics themselves. “At their best,” he wrote, “EC was easily on par with the best pulp fiction available. And, if specific individual stories were considered, many of them were a good deal better, both in originality and concept and completion of expression….If any popular writing deserves a claim as literature, this does also. They were, at their best, mature conceptions totally explored, and with a constant attitude toward realism and honesty mixed in with the short, sharp crackle of drama.” What we can detect on cold hindsight is a young reader’s devotion, mixed with an instinctive understanding that the comics he was reading were still lodged in the ghetto of world art.

A few decades later, the EC line occupies no less than 4 spaces in The Comics Journal’s Top 100 comics of the century list, a ranking exercise which should put paid to any claims that this magazine has an elitist stance. The question for today’s readers is why a line consisting of “the best pulp fiction” and sometimes “a good deal better” is still considered among the best comics ever made.

Some of the answers to this question are quite apparent, among them a blindness and mule-headedness born of nostalgia. These are rose tinted lenses that have adhered so tightly to the eyes of most comics critics that they cannot be eradicated without immense difficulty. Suffice to say, the judgements made by critics and readers in assessing their favorite art form are firmly entrenched in their childhoods.

But first, a possible exception.

Mad #1-20

It is only in the case of Mad that EC manages to justify a degree of its reputation.

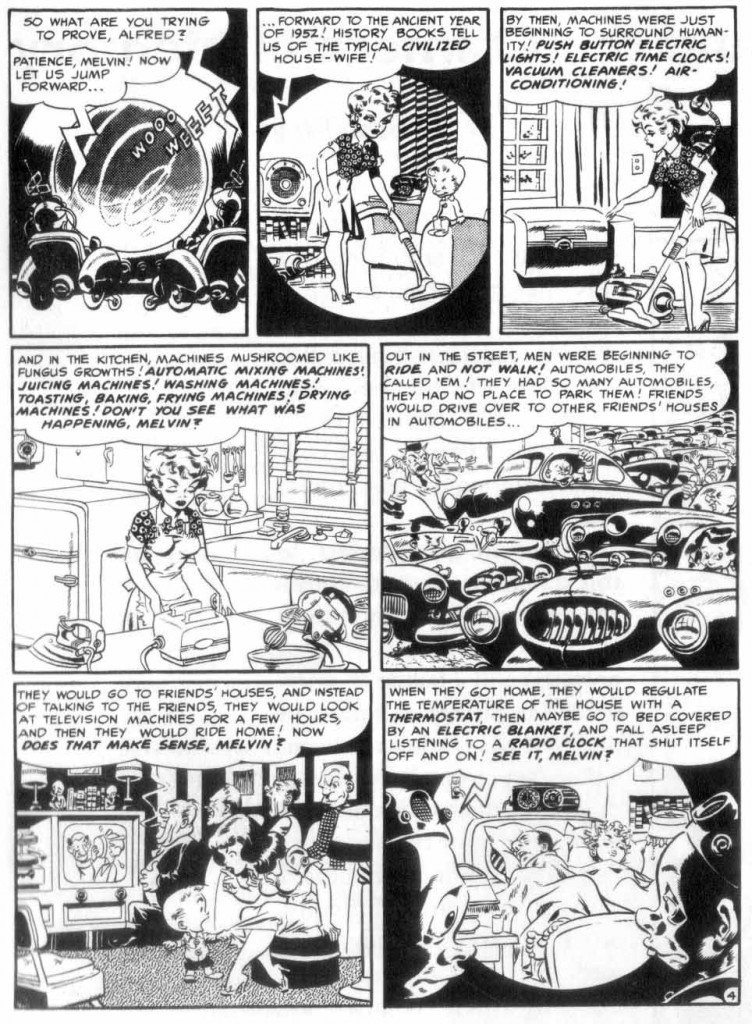

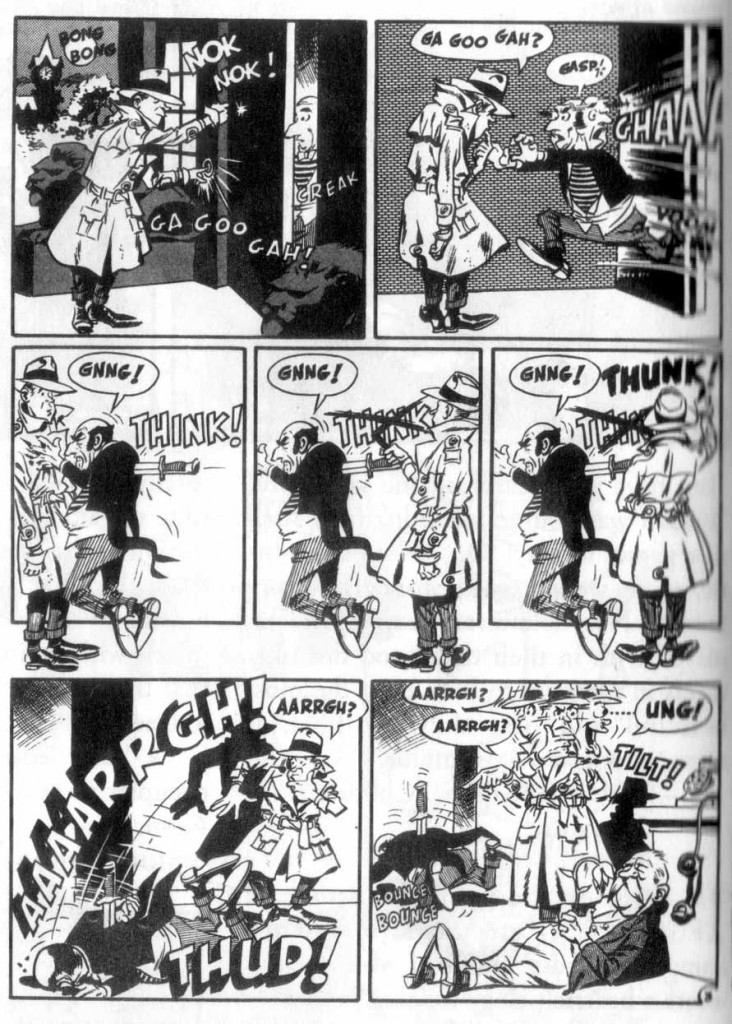

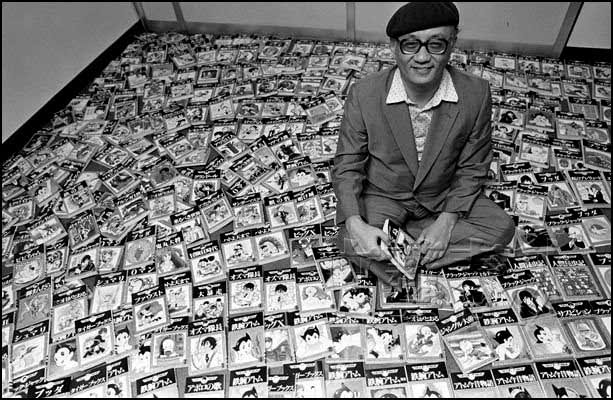

Enough has been written about the merits of these issues that I will not bother dwelling at length on them. Starting somewhat bumpily with plots which read like standard non-humorous EC texts (only with “funny” drawings) before proceeding to parodies of television shows, classic strips, and various DC and pulp heroes, these early stories were adorned with endless visual treats, immaculate artistry, a number of classic Hey Look! reprints and a set of outstanding covers and cover concepts. Kurtzman was undeniably a master of the form and the influence of Mad on American and European artists is inestimable. The strongest legacy of Mad would appear to be a certain subversivness and visual invention. In his introduction to Harvey Kurtzman’s Strange Adventures, Art Spigelman virtually admits that we wouldn’t have Raw magazine as we now know it without the influence of Kurtzman’s Mad. Writing in this magazine, R. C. Harvey insists that “almost all American satire today follows a formula that Harvey Kurtzman thought up”, a statement which I would not care to dispute.

Such influences may suggest a certain level of quality inherent in the series but cannot be the sole basis upon which the greatness of Mad is built. Objectively speaking, there is a lack of timelessness, consistency and universality in these early issues.

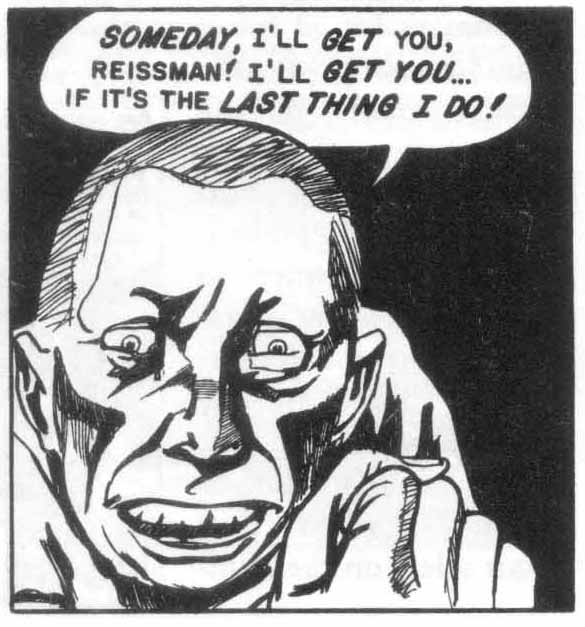

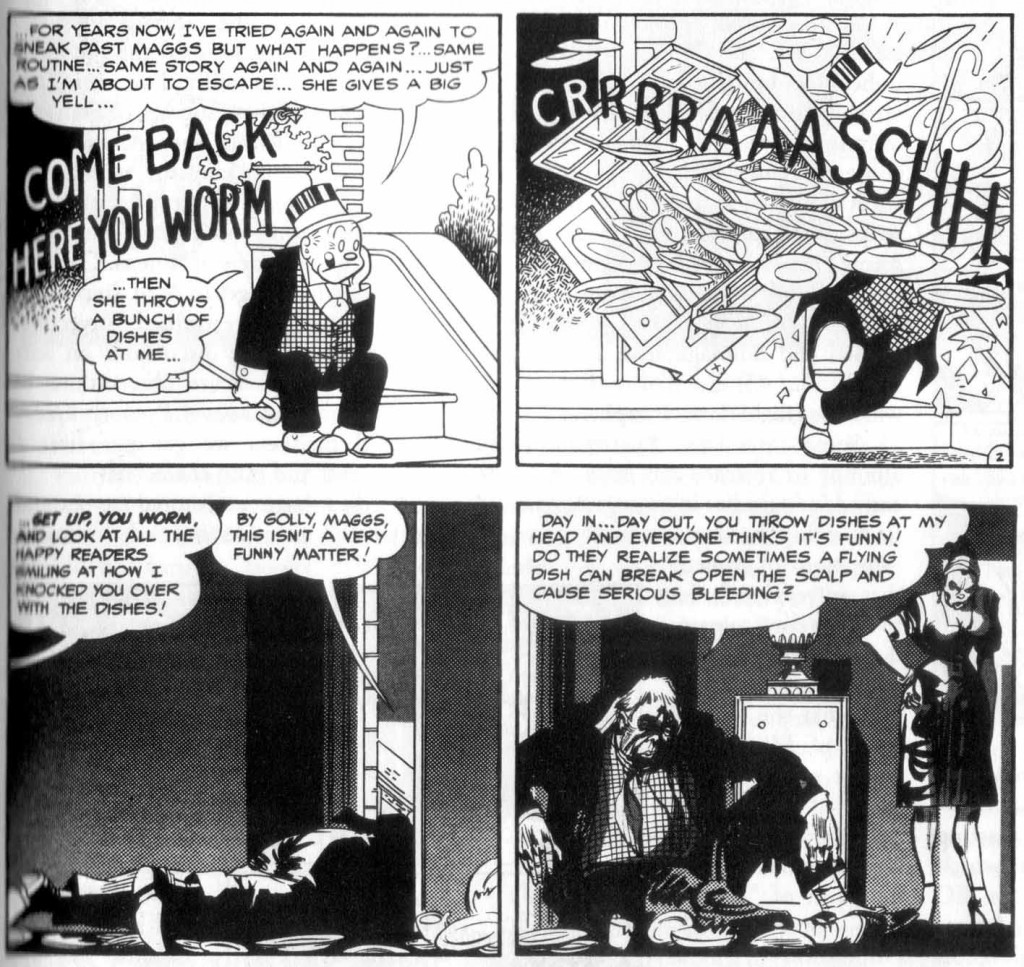

For every “Flob was a Slob”, “Superduperman”, “Little Orphan Melvin!” and “Bring Back Father!” (a Kurtzman and Krigstein masterpiece) there’s something wordy and dismal like “Black and Blue Hawks” (which is still undoubtedly loved and appreciated by some) and “Smilin’ Melvin!”.

Outside a Western context (one which is immersed in the substantial back catalogue of classic strips, pop artifacts and comics), Mad seems almost irrelevant, incomprehensible and dull. Would anyone consider “Blobs!” (Mad #1) or something as cliched and unimaginative as “Dragged Net!” (Mad #3) essential reading (because that’s what the label classic implies)?

Some years later, Kurtzman would attempt to recreate the magic of these early Mad parodies in Strange Adventures. In so doing, he demonstrated the severe limitations of comedy restricted (for the most part) to parodies of genres or existing works of art (for this is what the first twenty issues of Mad largely consist of). Nearly ten issues of Mad go by before formula gives way to innovation in the form of “Murder the Story”, “3-Dimension” and “Book/Movie” culminating in the issue 20 story, “Sound Effects”. These are stories which do not receive the acclaim or nostalgic turns of the parodies but were important in adding a certain potency and variety to the mix being accomplished pieces of proactive humor, an area which is inherently more difficult to explore.

Yet, through these early issues (and for a considerable length of time following), the writers and artists of Mad consistently failed to divorce themselves from their roots in parody and second hand satire, the unwavering elements that had endeared the series to a legion of readers. EC fans hardly ever mention these early pieces of proactive humor and I suspect that part of the reason is that children prefer the more straightforward humor of the parodies and find a certain comfort in humor directed at familiar targets such as Superman and Tarzan. The adults that have developed from these roots consistently fail to extricate themselves from this position.

As a kind of bible of pure comedy, the early Mad falls remarkably short of perfection however influential. Where is the personal slander, the rambunctious sex, the mad philandering, the sublime depravity and the political skewering we expect of the richest sources of comedy? Over two millennia ago, Aristophanes was brilliantly mocking the tragedies of Euripides (Women at the Thesmophoria) and risking prosecution with forthright attacks on the leaders of Athens. Contrast this with what we get in Mad. In place of Aristophanes’ unrestrained invective, Shakespeare’s poetic discursions on self-delusion, Wilde’s acute observations of social norms, and Monty Python’s Dada flavored madness we get parodies of superheroes and pulp characters.

Critics have attempted to extend Kurtzman’s parodies beyond witticisms concerning the immediate pop culture products they lampoon, suggesting rather a primary preoccupation with societal ills but this is plainly ludicrous when one looks closely at acknowledged “classics” like the second “Melvin of the Apes” story or “Ping Pong”. It is certainly true that Kurtzman managed to achieve many of these ends over the course of his long career but the early issues of Mad—the ones which have attracted the most reverence—represent something cropped and stilted, not so much unworthy as failing to exploit the full measure of the history of comedy.

Further, one wonders if the consistent elevation and reverence of Mad asserts a more insidious influence on American funny books. Within America (and this excludes a whole slew of modern and classic foreign titles) there is an extraordinary paucity of long form works of comedy. Decades of imitation and decay have left us with a small clutch of longer works including Feiffer’s Munro and Tantrum, Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary, Hate and the debatable merits of Epicurus and Why I Hate Saturn. There is little doubt that such developments are largely a function of the nature of the American market and its economic realities—namely its dependence on short form works until a few decades ago—but one wonders if it is symptomatic of a paucity of ambition and discipline among creators of comedy.

The prevailing culture of comedy in comics has somehow managed to convince artists in the field that where humor is concerned, brevity is the only form that they need consider. They have no finer ambitions than being gag men. What was once a dictate of business and the economy has now become the creative norm. The flurry of third rate parodies which were released during the black-and-white explosion of the late 80s and early 90s were the nadir of this tradition, the product of artists who failed to see the inherent limitations of this form of expression and who refused to broaden their horizons. It was an almost inevitable end point for a form so tied to its merely acceptable roots. The classic issues of Mad were an important step in the refinement and articulation of a language. They should not be considered or treated as if they were the final flowering of a genre.

The EC Horror Comics

“Oh I think you’ll find the further back you go the better they were. But simple; they weren’t classy. They weren’t great literature, but they were good. Like horrible…Yeah, they were all right. If you start judging them as works of art, you’ll never get anywhere. Judge by the fact that they were comics books written for fourteen-year old kids, sixteen maybe – we never thought we were hitting any higher than that in the beginning – who just like a good scary story to make it rough for them to go to sleep.”

Al Feldstein, from an interview in Tales of Terror

There are certain comics and stories that form the solid bedrock upon which the reputation of the EC line has been based. One of the least creditable of these foundations has to be the comics of the three major EC horror lines.

The EC horror titles as a whole have failed to generate any intelligent discussion or analysis apart from their relationship to American pop culture, the Kefauver hearings, and Seduction of the Innocent. In short, most appreciations of the EC horror line are largely bereft of genuine aesthetic considerations often boiling down to pronouncements that they were fun, influential, irreverent, and exciting for children.

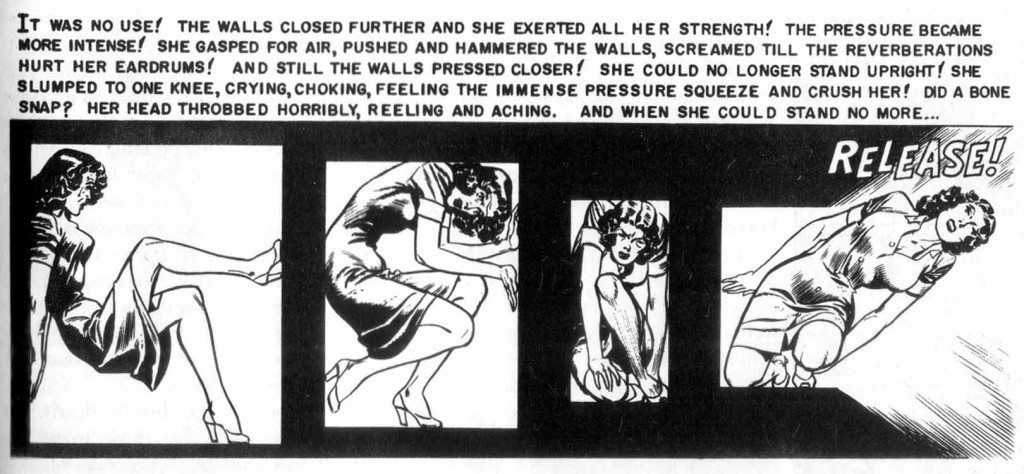

I am not suggesting that children should be deprived of profane fantasy but the finest children literature (and this is what is being claimed for EC) does not permit such concerns to overwhelm a certain truthfulness and sophistication. However much we admire the black humor of these stories, there should be more to a good children’s comic then unabashed glee at decapitated body parts roasting on a barbecue, choppers sliding into human heads, fermenting appendages, and zombies feeding on human flesh.

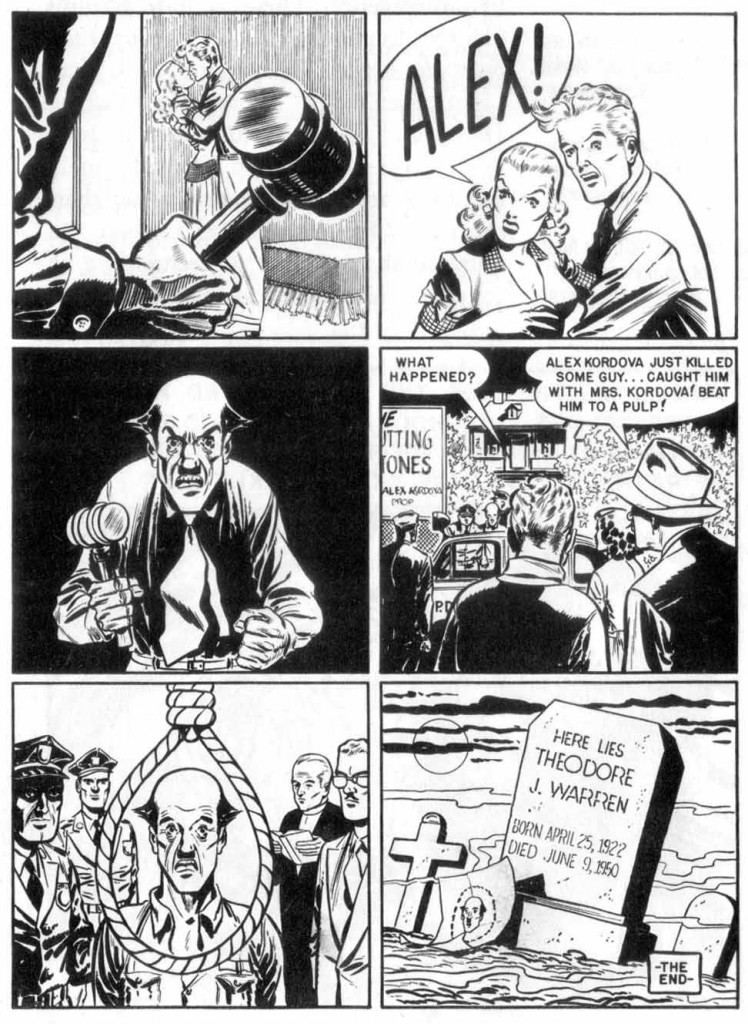

The primary emotions and personalities of the characters within the horror titles almost never (aside from the occasional doting wife who gets impregnated by her dead husband) extend beyond the limited values of hate, lust, covetousness, and fear. The recycled plot ideas provide the same sense of security children today feel when they watch episodes of Pokemon: the fetish (voodoo dolls, statues, and paintings) device; the lover’s return from the dead; the buried alive motif; the horrible unmasking shock ending—all of these and more are looked upon with affection and charity rather than with disdain and boredom. More platitudes can be found in the infamous retribution endings which the EC writers were unable to extricate themselves from even in the context of the early issues of Mad: don’t mess with witchcraft or you’ll be buried alive or catch leprosy; please don’t murder or you’ll be consumed by a zombie and do not covet thy neighbor’s spouse or you’ll be electroplated, decapitated, or buried alive. All of which, I’m sure, are fine upstanding lessons for a child but hardly the stuff of greatness.

There are examples of stories that are possessed of some narrative and sequential intelligence. These include Johnny Craig’s “Impending Doom” from Tales from the Crypt , “Whirlpool” and “Star Light, Star Bright” from The Vault of Horror and Gaines, Feldstein and Davis on “Let the Punishment Fit the Crime”. But these are the exceptions rather than the rule. One must wonder where we lie in the aesthetic understanding of comics if we must continue to admire stories because they are campy and merely well drawn. Shouldn’t such childhood experiences be confined to an aesthetic boothill alongside like-minded, nostalgia-laden refuse like The Twilight Zone and The Outer Limits? Why not rather rest our sights on stories that are well written and possessed of mature insights that are communicated with delight and horror to their young readers?

In Tom Devlin’s abandoned essay concerning the legacy of EC (TCJ #238), the benefits of a more cartoony style were touted as a superior form of expression in comparison to the tendency towards realistically drawn art in the EC line. This is a false dichotomy which restricts the merits and qualities of “realism” to a handful of mediocre comics. One could cite a number of realistic (and I use this term purely in its comic book parlance) artists and series whose merits far exceed those of a whole generation of “cartoony” modern American artists: Alberto Breccia, Dave McKean on Cages, Schuiten and Peeters on the Les Cites Obscures series, Moebius’ Airtight Garage, Taniguchi on The Man Who Walks and Sakaguchi on Ikkyu.

If there are indeed any trends which EC encouraged these would be an over-reliance on illustration over the narrative powers of comics and the cultivation of a critical inability to look beyond that which is simply well executed. The EC line has fostered, encouraged and deceived a legion of artists (as well as readers and critics) who remain content with finding a safe and commercial style upon which to earn a living and who do not find any value in discovering new avenues for their craft or intellects.

Even so, the EC line is clearly not solely responsible for these prevailing trends and attitudes. They may be seen merely as the symptoms of an insidious cancer or virus; constrained irreparably by commerce and reinforcing beliefs by their firm entrenchment in the popular tradition of comics. Their continued reverence suggests how little ground we have gained in the intervening years.

EC’s Science Fiction Line

“The EC approach in all these books is to offer better stories than can be found in other comics. At EC the copy itself – both caption and dialogue – has taken the number one position. This is a switch from the old days of comics when the art was most important and the story secondary. We take our stories very seriously. They are true-to-life adult stories ending in a surprise.”

Wiliam M. Gaines, Writer’s Digest

The EC science fiction collections, (most notably Weird Science, Weird Fantasy, and Weird Science-Fantasy) present smaller pillars in the edifice that we are discussing. Not surprisingly, the arguments for the qualities of the EC Science Fiction line are largely similar to those extended for the horror comics.

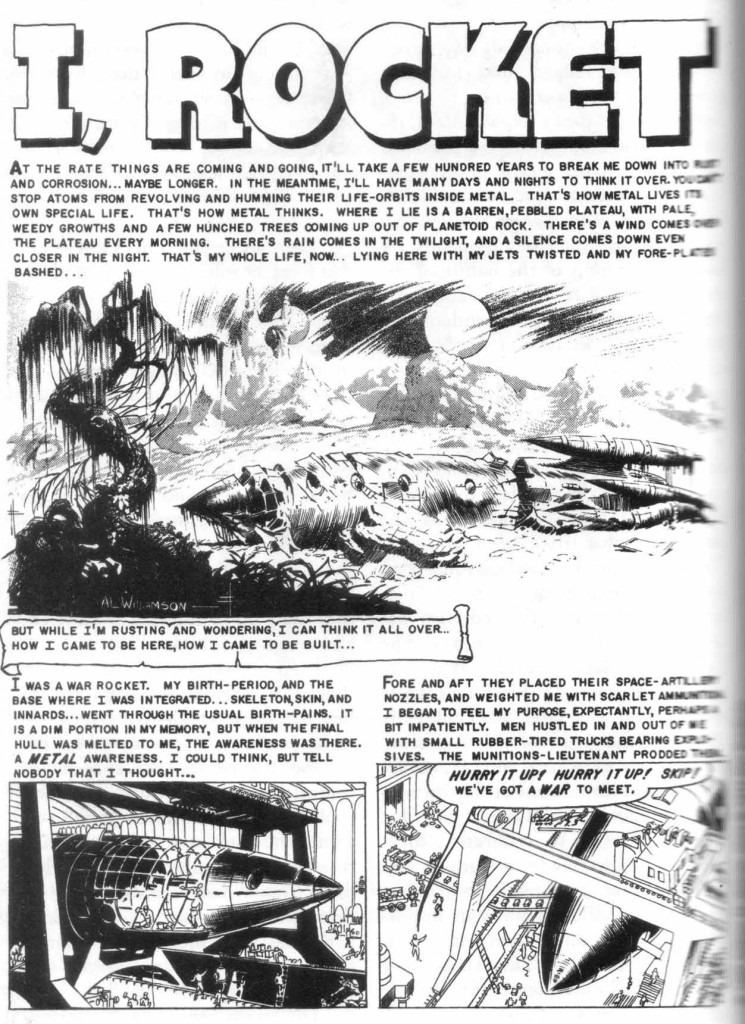

I will spare readers of this essay any detailed rants concerning the extended sermonizing of “classics” like “Judgement Day” or the regurgitated nonsense of “He Walked Among Us”. Suffice to say that the most coherent and imaginative of the EC science fiction comics were the Ray Bradbury adaptations; stories such as “I, Rocket”, “The Million Year Picnic”, “There Will Come Soft Rains” or “The Flying Machine”. Yet these retellings do not bring us fresh perspectives or revelations and exist as insignificant appendages to the original stories.

An inexcusable proportion of these adaptations amount to illustrations of text with a scattering of dialogue balloons, a manifestation of the way EC’s stable of writer’s and artist’s worked on their stories during their short deadlines. In so doing, they provide further credence to the belief that comics are indistinct from illustrated prose, a position which is no longer tenable aesthetically in the light of modern day advances in graphic storytelling.

In the 1950s, Bradbury was writing alongside the likes of Robert Heinlein, Arthur C.Clarke, Fritz Leiber, Brian Aldiss, and Alfred Bester. Later years would bring us the classic works of Philip K. Dick, Harlan Ellison, John Brunner, Ursula K. Le Guin, J. G. Ballard, Roger Zelazny, and Gene Wolfe. Beginning with their imaginations and ideas, these writers charted a path through literary science fiction into acute considerations of the artistic aspects of their chosen genre.

Science fiction in American comics, on the other hand, is dead. Quite frankly, there is little we should expect from a genre where a handful of weak fantasies created in the 1950s are still seen as the bench mark for all future works. Rather than advancing with the literary giants in the field, comics writers and artists have been crippled by the conservative and unenlightened trends so prevalent till this day in science fiction art and illustration. These are the very values which EC fans continue to cling to when they focus solely on the flamboyant artistry of Frazetta, Orlando, Williamson, and Wood to the exclusion of all else. We should be filled with pity not despair at their ignorance.

Crime and Shock SuspenStories

The one clear distinguishing mark of the SuspenStories lines were the tales of social conscience (the so-called “preachies”). Apart from these, both these series were largely indistinguishable from the EC horror and science fiction lines with their mishmash of stories of retribution, “suspense”, and “shock”. EC fan and historian, Digby Diehl, even deigns to suggest that Shock SuspenStories tended to offer up “a Whitman’s Sampler approach—often combining a crime story, a science fiction story, a horror story, and a shock story in the same issue” (Tales from the Crypt – The Official Archives). It is a comment that betrays the lack of ideological deviation in these comics compared to the other more focused New Trend comics. There is little doubt that the “preachies” lodged within the pages of the SuspenStories titles (in particular Shock SuspenStories) were daring, controversial moves at the time. Yet mere artistic courage cannot be the final arbiter in decisions concerning the absolute worth of a piece of art.

There is something dreadfully hollow beneath the noble veneer of these stories. The “preachies” were hopelessly didactic, simplistic, and inarticulate; failing at every point to delineate character or elicit sympathy for their cause. It is also notable that the same writers and artists who willingly allowed a considerably more lurid form of violence to pervade their horror and crime fantasies, patently failed to use these tools in a more truthful yet forceful manner when it came to depicting those stories grounded in “social realism”. Worse, this was “social realism” riddled with “white” lies.

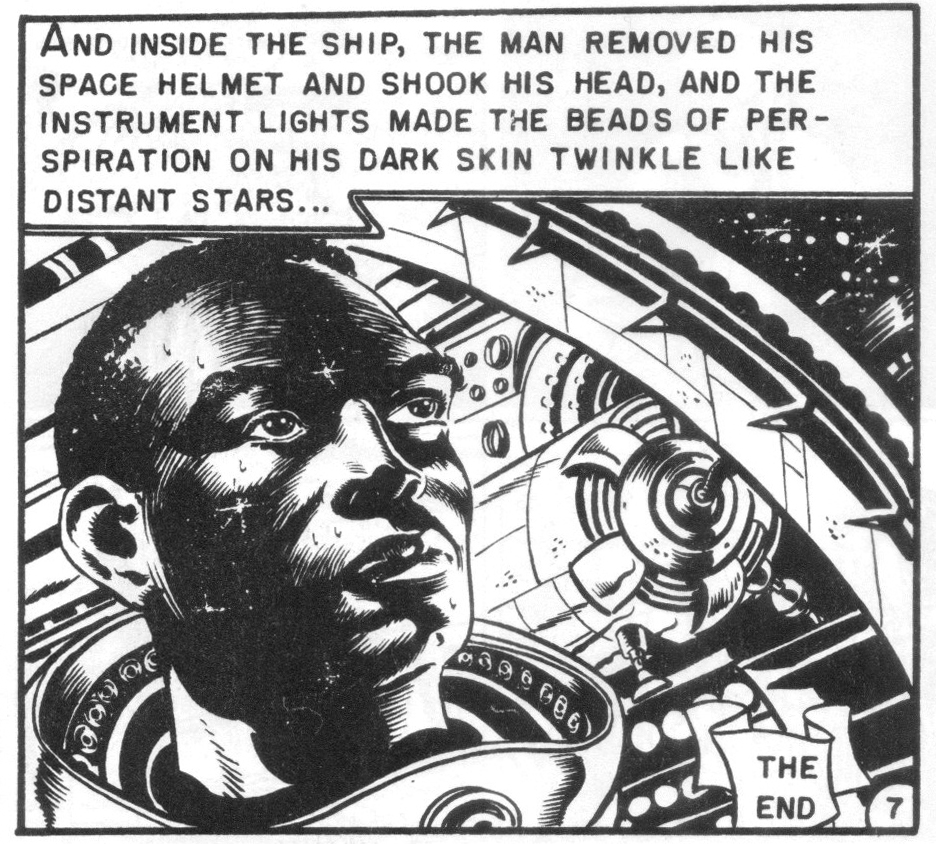

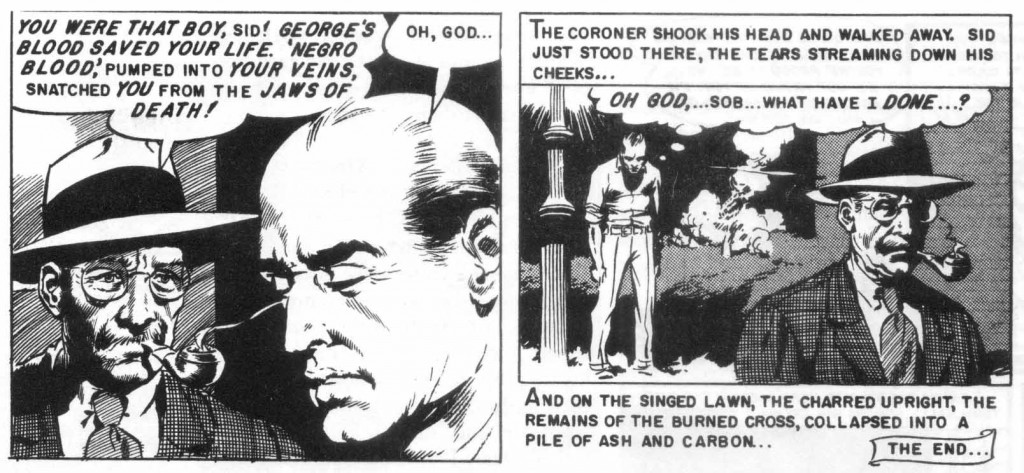

“The Guilty”, a story about injustice towards blacks in which an innocent black man is methodically murdered while in custody, rids itself of any sense of credibility with self-righteous, non-introspective editorial comment: “But for any American to have so little regard for the life and rights of any other American is a debasement of the principles of the Constitution upon which our country is founded.” The story “Blood-Brother” has a cross burning racist breaking down in tears of repentance when he discovers that he was once saved by some “negro blood” as a child—a somewhat implausible if not quite laughable sentiment in a country that was once more used to extracting every last pound of flesh from their black slaves. Pollyanna would probably approve.

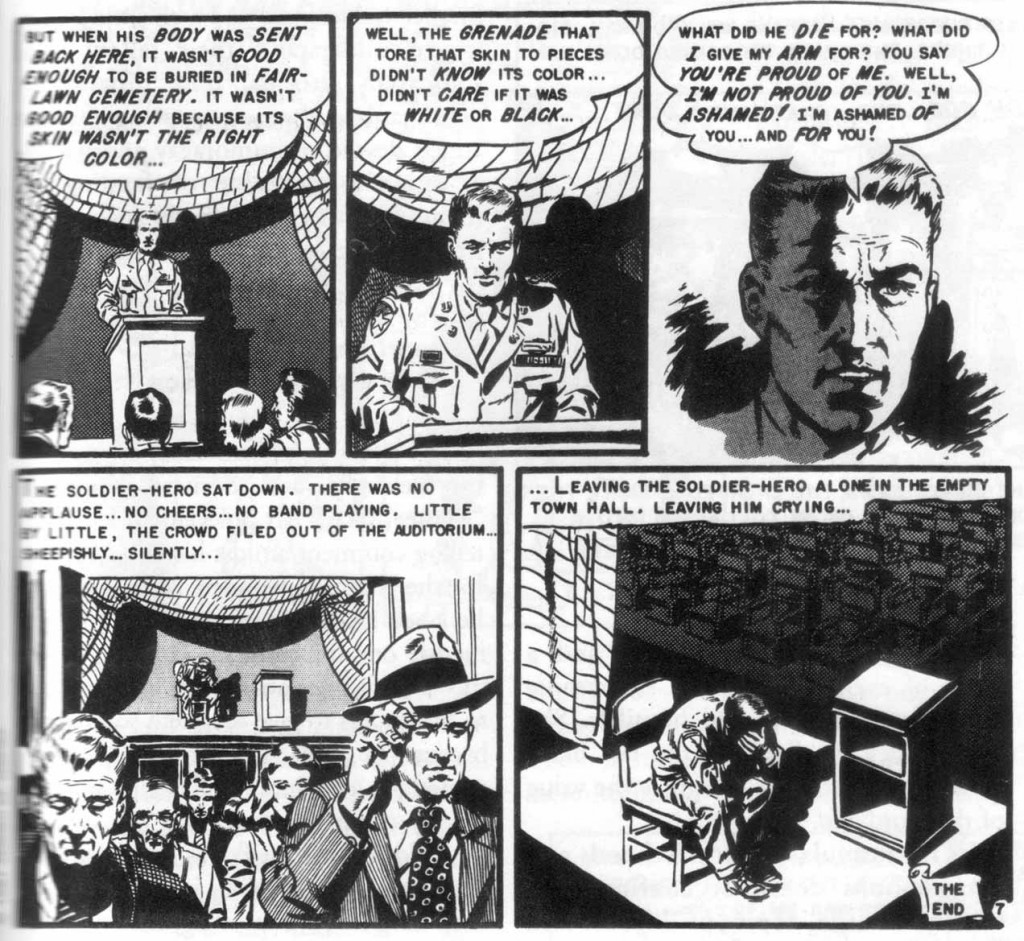

The typical EC African American is a silent, passive individual; an innocent without voice or passion in the face of society’s racism. There are very few exceptions to this. The black solider of “In Gratitude” is, admittedly, said to be brave, but is unfortunately quite dead. He is refused a burial plot on “white” land and his fellow white solider pleads on his behalf.

The authoritarian position of the black astronaut in “Judgment Day” (from Weird Fantasy #18) is little relief from this debased pattern. In the cloistered nunnery that is the EC SuspenStories line, the black man is dignified but not proactive; a sympathetic martyr not an angry, forceful activists. Yet a few years after these stories were published, Rosa Parks would step on a segregated bus triggering off the Montgomery bus riots and a series of events that would undermine and refute these lies and homilies. She was neither the first nor the last black person in America to recognize the value of the word “no.”

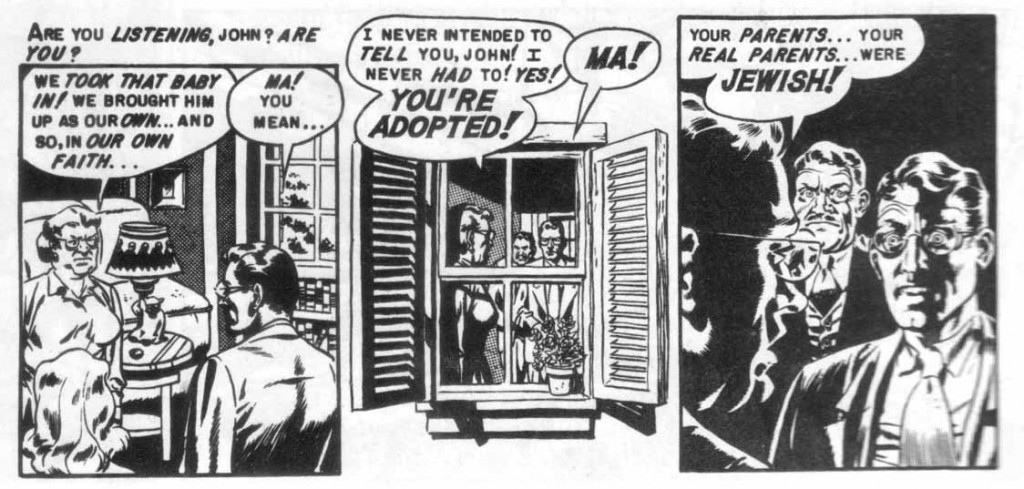

This formula of soft falsehoods and exaggeration does not confine itself merely to the topic of blacks and racism. In a public service message about drug addiction (“The Monkey”), the protagonist graduates swiftly from marijuana to barbiturates and then to the big “H” before losing control and killing his father. Devoid of any sense of irony, the story glosses over the more pressing (and common) medical and social problems associated with drug addiction, preferring to titillate its young audience with a “shock” ending. “Under Cover” and stories of that ilk are sullied by an overriding desire to simply entertain resulting in feeble if not ignorant attempts at needling lynch mobs, vigilante groups, and corrupt governmental agencies. “Hate” (a story about neighborhood anti-semitism) is a grotesque “What if you were a Jew too?” story devoid of clear ethical reasoning.

Like many modern day series, the SuspenStories comics were for and about white Americans. Stifled by a certain intellectual laziness and a chronic inability to understand their fellow non-Caucasian citizens, they unwittingly dehumanized them; presenting them as angels devoid of immorality and wretched enigmas incapable of fending for themselves. They are wholly anachronistic as far as race and societal relations are (or ever were) concerned despite their worthy motives.

Bernard Krigstein’s “Master Race”

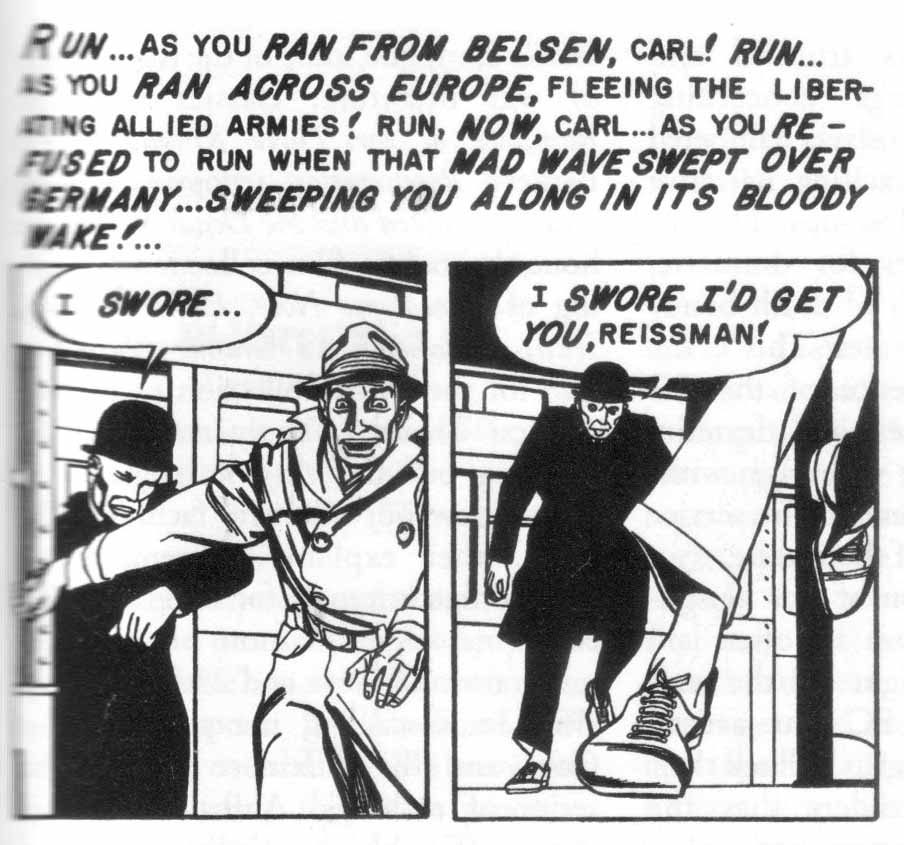

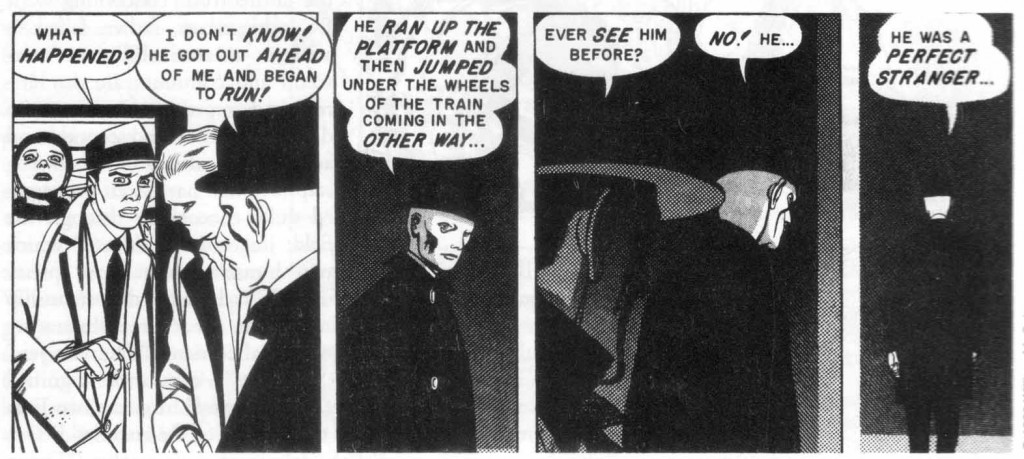

At one point in his famous essay concerning Bernard Krigstein’s “Master Race”, Art Spiegelman lets slip a telling comment amidst his effusive praise for the technical wonders of Krigstein’s story—he labels the subject matter of “Master Race”, “a thematically mature one for comics.” Thirty years on, this remark presents itself as almost a plea to his readers to give Krigstein some credit because he and Feldstein were tackling something a bit more challenging than the average children’s comic.

Feldstein himself was more realistic about his story, labeling it merely “good” with Krigstein “[improving] the art end of the story so much that I thought we were really breaking new ground.” Yet a feeble story, no matter how masterfully executed, should not be excused on the basis of mere thematic maturity, the very minimum basis of any adult work of art.

“Master Race” is, however, a children’s story. Perhaps a good (and this is certainly not indisputable) children’s story but still a children’s story. As a children’s story, it does not contain one iota of the humanity found in a thirteen year old girl’s famous diary during World War 2 enshrouded Amsterdam. It is pathetic that it should still be considered one of the finest stories ever created in comics.

One may wish to focus on the formalistic brilliance of “Master Race” to the exclusion of all other indicators of its decrepit nature, yet style and content cannot be divorced in what is clearly a narrative story. “Master Race” is not an exercise in pure experimentation like Richard Maguire’s “Here”, nor do such forays into experimentation and formalism forbid coherent, fully evolved content. Is it not possible, for example, to find substance in Godard’s Weekend or Bunel’s Discrete Charm of the Bourgeoisie?

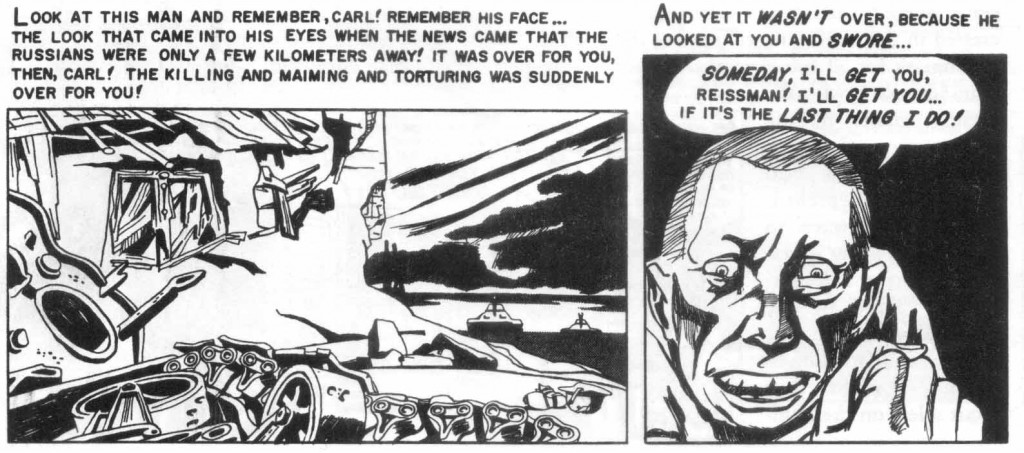

“Master Race” is revolutionary technical achievement illustrating banal sentiments. It is firmly entrenched in a certain hypersensitivity emanating from the protective glands of overbearing conservative adults and fails to extricate itself from a desperate adherence to the judicially blissful endings so typical of the EC line as a whole. In Feldstein and Krigstein’s make-believe world, revenge is consistently attainable and satisfying. “Master Race” is a deceitful fairy tale where every Jew has the chance to be an avenging Simon Wiesenthal and where Nazis don’t turn up healthy and wealthy on the political scene in Austria or as aged businessmen in France. All of which is perfectly fine for a middling children’s story but not for one of the greatest works ever created in comics.

There can be no room for excuses in judging the absolute worth of a story which is no more than 50 years old and created at a time when people were already steadily being made aware of the horrors of the holocaust. Great art doesn’t need excuses. Goya’s famous print series,The Disasters of War, is often cited in comics circles as one of the finest examples of the printmakers art (and perhaps a distant cousin of the cartoonist’s art). What we hear of less often is that Goya started his print series (amidst the chaos of the Spanish nationalist insurrection and Peninsular War) by scavenging for copperplates upon which to engrave. It was a series that was initiated from personal need and distress with little consideration for the economic realities of the time. Goya realized that he would never see the publication of his print series during his lifetime and it was only released 50 years after his death.

Truly great art is not shackled by commerce. It is born of a great artist’s insatiable need to create and to tell the truth. There is an artistic impulse behind “Master Race” but it is vastly inferior to that which we should expect of a master of the form. The constraints of entertainment and commerce have housed the work in mediocrity. No one should consider “Master Race” anything other than an above average cave painting on the path to greater things. An important first step perhaps but not one of the greatest works of comics art ever made. There is more to admire in Giotto than mere technical ability and perspective, more to Citizen Kane than a kaleidoscope of sumptuous camera angles, moody lighting, tracking shots, and deep-focus shots.

Krigstein had neither the desire nor capabilities to develop beyond “Master Race”, “The Flying Machine” or “The Catacombs”. Van Gogh stuck with his visions till the bitter end and Goya completed The Disasters of War with no sure knowledge that it would reach an audience. Krigstein, on the other hand, doesn’t appear to have kept his faith in the artistic possibilities of comics. At the very least, he did not act upon any remnants of this faith that remained following his departure from commercial comics. Nor did Krigstein show any clear genius for writing. As a consequence of this, he remained hampered by the mediocre to poor writing he was saddled with throughout his career.

The EC artists never felt themselves part of the rich tapestry of world art but merely as dedicated craftsmen. With these values in tow and without the unpredictable fortunes of genius, they failed to produce works of lasting importance to civilization. A high ideal perhaps but one which a nascent art form needs to grasp at as tightly as possible.

The EC War Stories

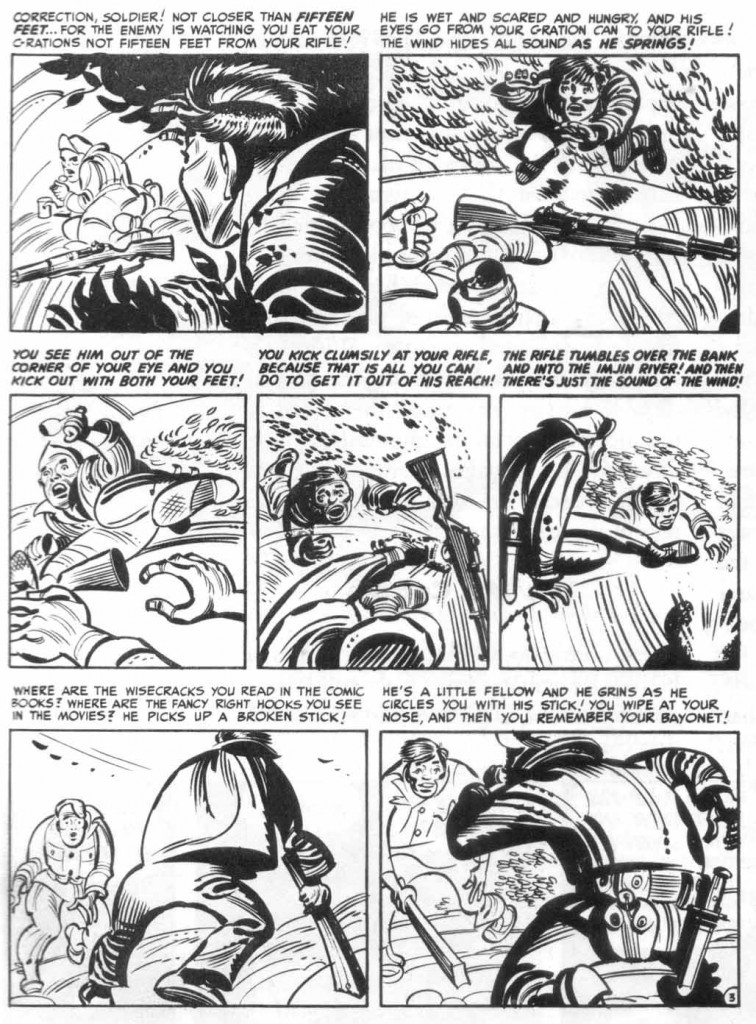

There is little doubt that the war stories of Harvey Kurtzman form a more solid foundation than the EC horror and science fiction comics.

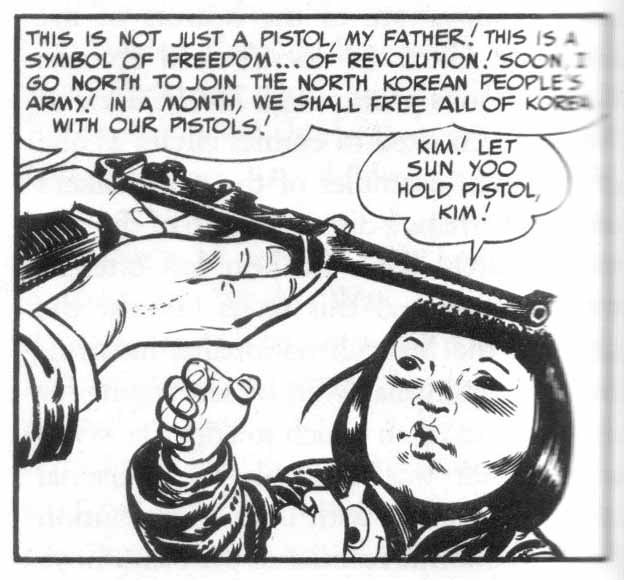

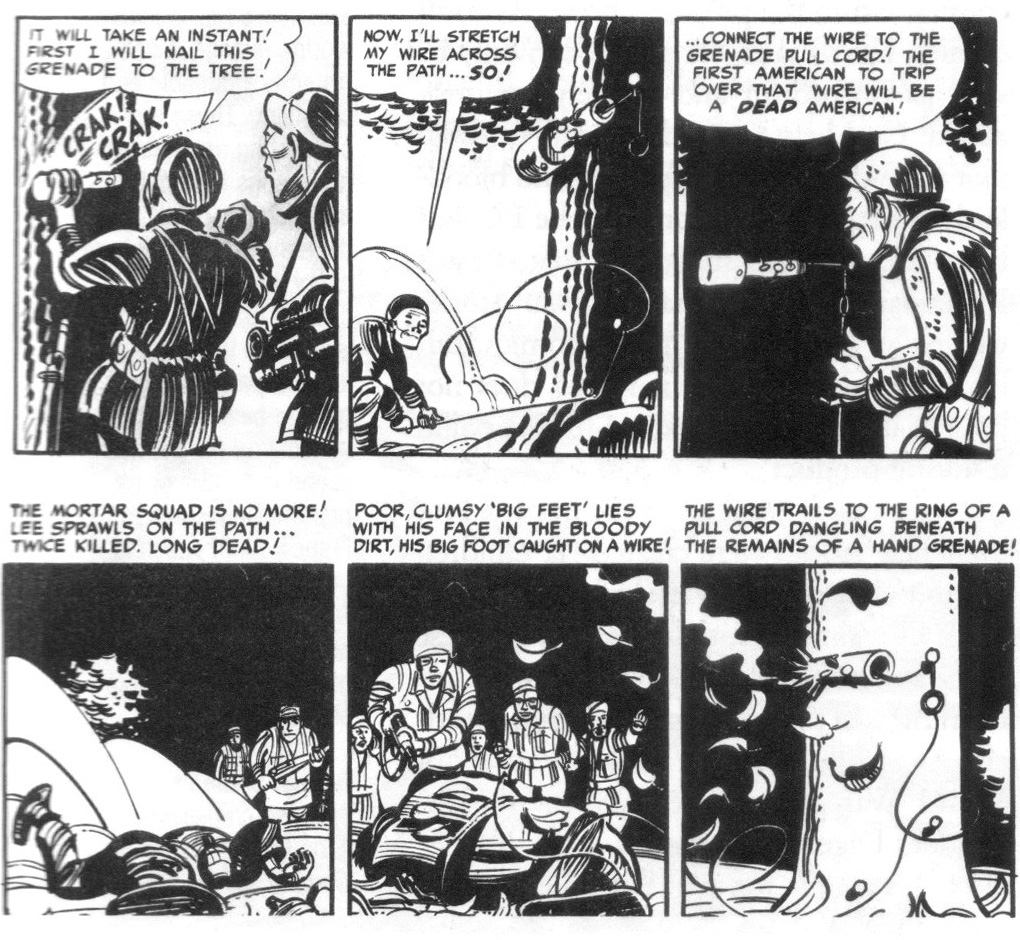

Burdensome as it may seem, I must reiterate the often neglected fact that the EC War comics must be viewed as children’s literature. I do not say this in a derogatory way but in order to set our discussion of these comics within the proper context. As adult comics, Kurtzman’s war stories can only be seen as untruthful and severely compromised; God help us if adults truly believed that war was as gentle, dignified, and bloodlessly pleasant as the stories of the EC War line. It has been suggested that it was Kurtzman’s decision that his war stories weren’t as grisly as the horror comics, but his squeamishness in this regard does not present itself as a valid excuse for the pallid resulting product.

And this is the crux of the matter: not that these stories were created for children but that they glorify by exclusion and by failing to relate life’s simple truths. In so doing, these comics commit the grievous sin of misinforming and patronizing their young readers. As a child, the first book I read about World War 2 was the 1969 edition of Reader’s Digest Illustrated History of World War 2, a simple tome of articles that chronicled with photos the horrors of Buchenwald and the horrendous deaths on Iwo Jima and Guadalcanal. I was neither frightened nor permanently scarred in the process. Children are not the fragile, ignorant creatures we think they are, nor are they incapable of understanding the mere realities of human existence.

Once we recognize this, we must begin to wonder why some of the most esteemed critics in the field so often choose to place these comics over any other series of adult war comics. Do we find Joe Sacco’s truthful and engaging writings concerning Palestine and Yugoslavia hampered by his lack of exciting narrative technique and close-ups? Do our healthy appetites for dramatic, swanky portrayals of death betray our immature desires? This is the corrupting influence of the EC War line: artfulness and dexterity in place of truth; voyeurism without horror; content in the service of style instead of the reverse.

In recognition of this ill-concealed fact, excuses are often laid out to add weight to the deft artistry of the EC war artists. Critics and apologists will tell their half-informed readers that the depictions of war were not consistently glamorous nor the deaths steadfastly patriotic in contrast to the other war comics of the time. But such comments fail to reveal the entire truth concerning what EC achieved or, rather, failed to achieve—an inability to transcend and communicate the horror and repugnance of stories drawn from first and second hand accounts, resulting in misleading staples which have been propagated quite thoroughly through the field: jingosim (see “Contact!”; which Kurtzman himself admits was “pretty dreadful stuff”); dramatic draftsmanship and intelligent structure illustrating inconsequential content (“Thunder Jet”, “F-86 Sabre Jet!”); exquisitely dignified corpses (“The Caves!” from the Iwo Jima issue); …

… the poverty of the enemies’ beliefs and the failure of their resolve (“Dying City!”);

…sanctimonious depictions of the plight of good, honest, salt of the earth Koreans (Southern presumably; in “Rubble!”); retribution for cowards (“Bouncing Bertha”), traitors (“Prisoner of War!”) and grinning, nefarious enemies (“Air Burst!; were there ever any breathing, happy North Koreans at the end of each story?).

As Walter Benjamin put it, “Children want adults to give them clear, comprehensible, but not childlike books. Least of all do they want what adults think of as childlike. Children are perfectly able to appreciate matters, even these may seem remote and indigestible, so long as they are sincere and come straight from the heart.” To a certain extent, Kurtzman managed to achieve these ends in stories such as “Big ‘If’!” and “Corpse on the Imjin” but they are the exceptions—exceptions which sadly persist in gaudily adorning themselves with too much artifice and too little truthful, engaging emotion.

Shouldn’t we entertain a degree of embarrassment for placing the EC War stories alongside some of the finest works of war literature; classics like The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, Catch-22 and The Naked and the Dead? Would we honestly trade a film collection consisting of Apocalypse Now, Paths of Glory, Ivan’s Childhood, La Grande Illusion, or Ran for the entire collection of EC war comics? There is simply no excuse for allowing our unseeing nostalgia to so overshadow our aesthetic faculties. The only other explanation remains an overindulgent respect for some acknowledged masters of the form.

I return to Goya and The Disasters of War. Fred Licht in describing the modernity of Goya and the difference between his series of etchings and Anibale Carracci’s images of public hangings and Jacques Callot’s Troubles of War, states that

“…[Goya] forces us to see with our eyes, not with his. The critic who draws attention to Goya’s ability as an artist actually does Goya a disservice. Images such as these are clear evidence that the artist intends to be exclusively preoccupied with the unbearable inhumanity of what is happening before our eyes. In the face of what happens all around us, the talent and the ingenuity of the artist seems trivial.”

And yet here we are, over a century later, still enmeshed in debates about the merits of dramatic structure and pacing in Kurtzman’s stories about war. And why are we still here? Simply because there is little more to suck from these stories than this. As factual and humanistic documents, they are empty and irrelevant; so bereft of revelatory truths for children that they have become obsolete.

One hopes that we will soon be reaching a turning point in comics; a point at which one can look back at these comics of our youth and say with honesty that they were mediocre, even as children’s comics. A point where we can truthfully say to ourselves that we’ve grown up, that we now understand and appreciate the complexities and emotional depths the best works of narrative art should communicate. We’ve been mucking about in the sandbox for long enough.

[The EC War comics are discussed in greater detail in Part 2]

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.