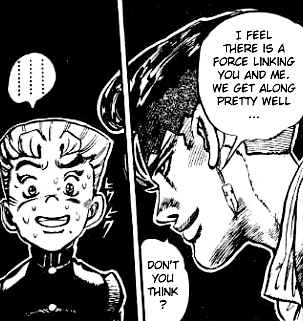

“I can’t tell if it’s a gay manga disguised as a battle manga or an adventure series disguised as a fashion magazine.” –fan reaction to Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure

Araki Hirohiko is an immortal vampire, and also the author of long-running Shounen Jump manga series Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure. According to Wikipedia, Jojo is “Shueisha’s second longest running manga series at 106 volumes and counting (only Kochira Katsushika-ku Kameari K?en-mae Hashutsujo, with over 170 volumes, has more)”. I can’t do a better job of summing up this series than Jason Thompson, one-time Jojo editor, so I suggest you go over to House of 1000 Manga to read his summary/review. The quote above pretty much nails it, though I’d also add that Jojo is a horror manga disguised as a superhero comic – or vice versa – an especially strange combination as the two genres are opposites. (Superheroes are a fantasy of absolute power while horror is a nightmare of absolute powerlessness.)

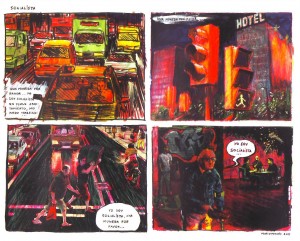

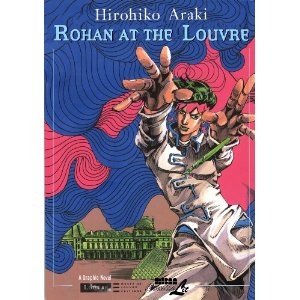

Recently, the Louvre Museum in Paris published a standalone short story set in the Jojo universe. This book is titled Rohan at the Louvre, in the manner of a museum exhibit. Plot-wise, it’s a horror short story with side-trips into other pulp and literary genres. Art-wise, it’s like 50 pages and full color!

Lots of people have written about Jojo before: it’s artsy enough, strange enough, and superhero-inspired enough to be right up HU’s alley. With the recent book out (in English!), however, now’s as good a time as any to revisit the series. In other words, even though Jason already said it all, I’m going to say it all again. I’ll be talking about Jojo proper in this entry, and the recent book, Rohan at the Louvre, in another entry tomorrow.

I.

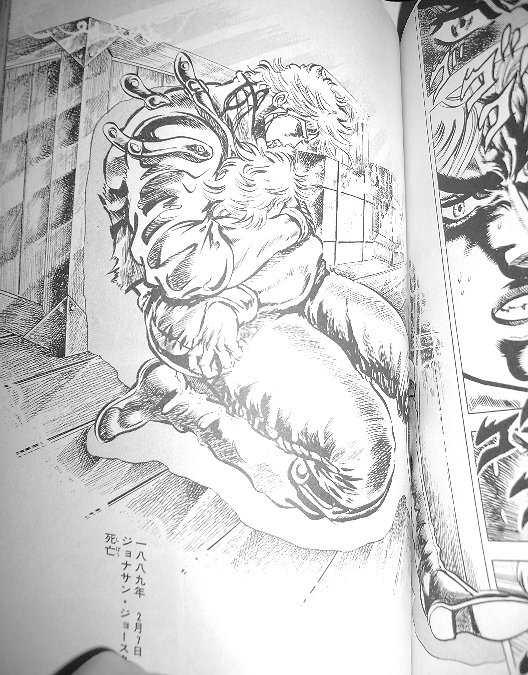

Though it’s considered a single long-running series, Jojo is divided into distinct arcs with different characters, different plots and different artistic/literary/pulp antecedents, each starring a different member of the Joestar family. The first arc is set in Victorian England and stars the heroic Jonathan Joestar, a buff young man in the vein of early 20th century U.S. pulp comics (i.e. highly muscular and highly anatomically incorrect). In an arc inspired by Victorian Gothic horror, he is locked in a private psychological battle with the evil Dio Brando, his adopted brother, taking place largely in their father’s large country mansion. However, when their father dies, the comic takes a turn toward Edwardian pulp adventure, as Dio becomes an immortal vampire, takes over a castle in Scotland, and converts a number of people (including, if I recall correctly, Jack the Ripper) into his zombie minions. Jonathan Joestar must then learn the mystical arts of Hammon, or ripple-energy, from a mysterious wandering Italian, while fighting off subvillains including an evil Fu Manchu-ish Oriental. In an iconic scene, he defeats Dio and clutches his severed head as they both sink to the bottom of the Atlantic.

Forever embracing, Jonathan Joestar and the severed head of his evil adopted brother.

II.

In the sequel arc, Johnathan Joestar’s grandson, Joeseph Joestar, a buff young man in the vein of influential Japanese battle manga Fist of the North Star (e.g. with three-dimensional shaded muscles which are relatively more anatomically correct), travels around the U.S. fighting Nazis and Aztecs, in a series inspired by Indiana Jones and the 40s pulp comics that inspired Indiana Jones. In this arc, the three ancient Aztec Gods who created the mask that turned Dio into an immortal vampire awaken from their slumber, disturbed by Nazi scientists. Joseph must use his strength, wits, and good looks to defeat them in honorable combat, along with reluctant ally/eventual best friend Caesar Zeppeli, the grandson of the wandering Italian of the previous arc. In contrast to the strong and righteous Jonathan, Joeseph Joestar is righteous and devious, delivering speeches about honor while finding a smarter way to win.

III.

Following this arc, Joeseph Joestar’s grandson, Jotaro Kujo, a half-British-American-half-Japanese high school student and buff young man in the Tom of Finland vein (i.e. muscular, smoldering, uniform-wearing, and continually provocatively posed) is forced to travel to Egypt in order to defeat a reanimated Dio Brando. This arc introduces the concept of Stands, or companion-spirits which are physical manifestations of psychic powers. Araki has said that he invented Stands in order to add visual interest to his drawings of psychic energy battles, and that they should be read as an artistic convenience or metaphor. This arc was heavily inspired by Araki’s own trip through India and the Middle East, reading at times like a battle manga, at times like a horror manga, and at times like a travelogue. In one chapter, the heroes might roundly and straightforwardly defeat a villain who has been attacking from a hidden location using a long-range power, delivering a dramatic speech about how his cowardly actions can’t be forgiven. In the next, they might fight off an entire village of zombie-fied Indian villagers without questioning the morality or logic of the horror-movie set up.

This hybrid-genre, adventure-horror, macho-slash-homoerotic-posturing arc is Jojo’s most influential, spawning a TV series and a videogame, as well as inspiring the designs of a number of fighting game characters (and the fighting game convention of travel to new location, fight, travel to another new location? Or did that come first? Whatever the order of inspiration, you can check this page for a list of Street Fighter characters based on characters in Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure). This arc is also the favorite of mangaka-collective CLAMP, who not only got their start with Clamp in Wonderland, a doujinshi (self-published comic) featuring the lovechild of Jotaro Joestar and best friend/fellow beefcake Kakyoin, but who have also been basing their stoic badass protagonists on Jotaro ever since. (One theory goes that CLAMP’s Wish is essentially Jotaro/Kakyoin fanfiction.)

IV.

In Jojo’s fourth arc, we are finally introduced to Rohan, the main character of Rohan at the Louvre. The balance between horror and adventure in Arc 3 was occasionally uncomfortable, as readers were asked to consider the unrighteousness of some transgressions by the villains while ignoring others as necessary scaffolding for the comic’s horror and gore. This is corrected in Arc 4, in which a more modestly buff Josuke Joestar, the surprise son of an aging Joseph Joestar, as well as a hot guy in the vein of 1970s Japanese working-class manga (i.e. with the same exaggerated Greaser hairstyle as Ryunosuke Umemiya of Shaman King), must investigate a series of strange happenings in his rural Japanese town. Going back to Araki’s roots as a horror artist, this arc is a mixture of horror and comedy. The lighthearted tone and small-town setting – the smaller stakes – allow Araki to draw endless pictures of exploding intestines without compromising the genre conventions of a normal Shonen Jump battle manga, which in the usual way of things would require a certain number of semi-serious speeches about hard work, friendship, loyalty, etc. Compared to the globe-trotting, super-villain-besting antics of the previous arc, this one sticks closer to home, going in for quieter, more refined psychological portraits of e.g. its illegitimate child of a single mother protagonist (and cleaner, less heavy art).

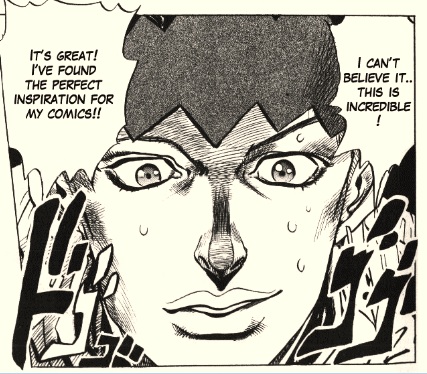

Rohan, the protagonist of Rohan at the Louvre, is introduced in this arc and immediately leaves a strong impression. You might be getting the impression that Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure is an extreme, comedic, violent, and somewhat strange comic. This is all true. Additionally, it’s a comic where many characters are very powerful and intelligent. Rohan, the author-avatar, is no exception:

Kishibe Rohan, Araki’s self-insert character who is also a mangaka for Shounen Jump

Rohan is powerful because his Stand allows him to open other people up like books, to read their thoughts and memories, and then to write instructions on their “pages” which they must follow even when these instructions defy physical laws. In other words, he can pretty much make anyone do anything. He also has the ability to alter people’s memories and to draw 20 pages in a split-second so that he’ll never miss his weekly publication deadline. Personality-wise, he’s arrogant, distanced, intense, and easily irritated – kind of a frightening person, really. It’s lucky for us that he’s not a villain.

To be clear, Rohan is not the most powerful person in this comic by a long stretch. There are people who can alter the laws of time and space in Jojo. Still, he’s pretty powerful! When he is introduced, Rohan’s powers only work on the first person to see a completed page of his manga, and then only if that person understands his art. Like all limitations, this is something he eventually forgets all about. With his trademark arrogant humility, he describes his abilities in Rohan at the Louvre as follows: “A trifling matter, of little to no consequence – indeed, I can literally read people like books”.

The next arc of Jojo is a turning point for the series, so I will discuss it even though we’ve already caught up with the backstory:

V.

Though it started out as almost a pure pulp adventure comic (albeit a very strange one), with each iteration the comic has become more prone to digressions into horror and comedy – or maybe just a bit smoother about those digressions, so that they feel more integrated into the overall tone. After all, Jojo was always pretty unserious, even when it was serious; and always pretty horrific, even when it was righteous. The characters also become slimmer: in the manga’s current run, they are toned like runway models or teen pop stars or soccer players, rather than like bodybuilders. They are also, increasingly, avant-guard and fashionable; and the major turning point for this change is Arc 5.

Arc 5 is set in Italy and is probably inspired by classical art and sculpture, as well as by European high fashion. This arc focuses on the adventures of Giorno Giovanna (GioGio), the son of Arc 3’s reanimated Dio Brando and an anonymous woman. Since the immortal vampire Dio survived his trip to the bottom of the Atlantic by attaching his severed head to the body of his adopted brother Jonathan (did I forget to mention this?), Giorno is a half-villainous and half-heroic character, a mobster whose goal is to be the ultimate Gang Star. Giorno is probably actually the “strongest” character in Jojo, with powers that eventually include rewriting the rules of physical reality.

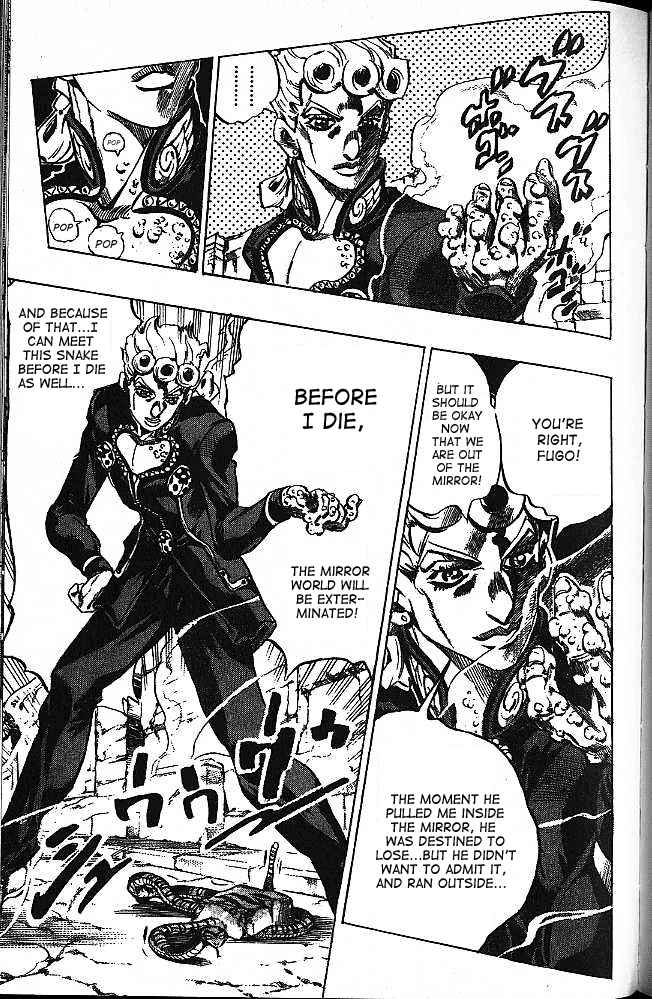

A friend of mine who visited Italy in part due to Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure swears that you can see the influence of classical renaissance art in (especially) the proportions and convoluted poses of the characters in this arc. Additionally, perspective becomes the subject of many drawings as strange mirror worlds, shapes, and cubes dominate the surreal landscape.

Giorno inside the mirror world

While the Stands in Arc 4 had powers which leant themselves to horror (e.g. the chef whose food was so delicious and healthful it made everyone’s intestines burst out), those in Arc 5 often have visually interesting and complex powers relating to the manipulation of space and time. This allows Araki to show off the skills he’s picked up since starting Jojo. For instance, there’s a villain whose superpower is to turn his enemies into cubes, while one of the heroes, Bruno Buccelati, has the ability to create zippers on any surface which open up portals into a subspace dimension. Araki’s interest in the manipulation of space was evident in the previous arc, as well – e.g. Rohan can open people up like books, a villain can turn people into paper – but is more fully developed and central to the action here. Somewhere along the line, Araki seems to have picked up an interest in physics and in using Stand powers to explore (and then exploit) physical laws.

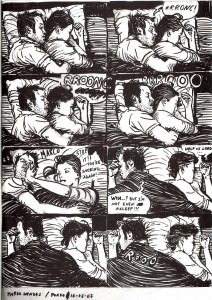

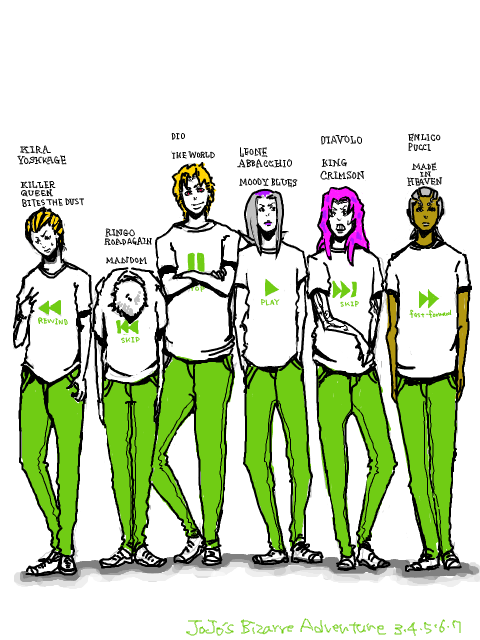

In addition to the focus on art, perspective, and the manipulation of space, Araki also plays with the manipulation of time, with several characters possessing the ability to speed up, slow down, skip ahead, skip behind, pause, or rewind time. I’m just going to leave this picture here for my fellow Jojo fans:

Now that you’ve seen it, you can’t unsee it, can you?

VI etc.

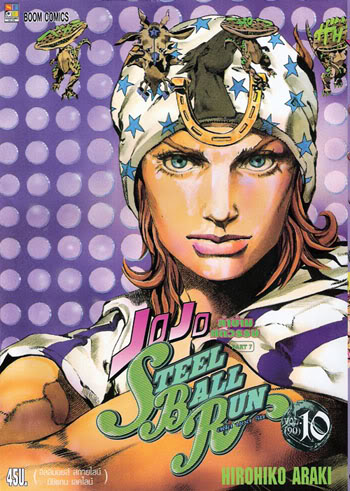

Arc 6 is set in a woman’s prison and continues Araki’s interest in melding horror, high fashion, and pulp, in addition to being possibly the result of a personal/editorial challenge to DRAW MOER WOMEN. (The protagonist, Jolyne Kujo, is Jotaro’s estranged daughter.) The arc immediately following is Steel Ball Run, a series reset in which Jonathan Joestar and Dio Brando, rather than being the children of a British Peer, are American cowboys competing in a trans-continental horse race. In a nod to the increasing psychological sophistication of Jojo, the heroic Jonathan is now a cripple, ruling out acts of physical heroism, while the villainous Dio, while still coming from a bad background, is now a complex and occasionally sympathetic character rather than one who is simply and irredeemably evil. More surprisingly, Johnny is not the arc’s main protagonist (that would be Gyro Zeppeli, a younger/hotter version of the wandering Italian from way back in the beginning). However, the characters still have great fashion sense:

Steel Ball Run’s Jonathan Joestar in his stars-and-stripes ensemble

That’s all of the (completed) arcs of Jojo so far. Tomorrow: Rohan at the Louvre!

Update: And the post on Rohan at the Louvre is up.