Homestuck: where to begin?

In a book I haven’t read, Rob Salkowitz “explores how the humble art form of comics ended up at the center of the 21st-century media universe” by talking about the mother of all trade shows: the San Diego Comics Convention. In this book, which again I haven’t read although I have read some excerpts on Amazon, he talks about how the focus of SDCC has shifted from intellectual property delivered via printed books to intellectual property that might, once, have been printed on a page, but that is bound to be far more profitable on screens: on movie screens, of course (though as with all good things the superhero movie boom must one day come to an end) but also on television and computer screens (TV shows, games) as well as tablet screens (digital serialization). Despite all this talk of “digital,” however, webcomics only get a few pages near the end of his book! And even then they are brought up largely as an example of artists who lack business sense! (Note again that I haven’t read the book.)

Nothing else in this article will focus on business, trade shows, superheroes, or the construction of what ruthlessculture.com calls trans-media megatexts. I only felt like I had to open with something appropriately journalistic or academic to fit in with the general tone of this website. “Trans-media megatexts,” however, is a label that might apply to a work like Homestuck, as I will discuss later on. Bear with me, I am going somewhere!

Homestuck is a multimedia webcomic with a large fan following, which as of November 9th of last year was 4,107 pages and 326,796 words long. That’s half the length of Atlas Shrugged, only taking into account page titles and captions. Words that come together with the art are a whole different story, and not included in this analysis because they are too difficult count. They are largely sound effects or image macro-style commentary on the action, anyway.

What enables this preposterously high wordcount is the inclusion of long chat logs below the art in which the characters comment on the action, crack jokes, and discuss their feelings. Because duh. How else would a group of teenagers who only know each other through the internet communicate while playing a cooperative computer game which can create and destroy reality?

Before getting any further into the plot of this comic, I want to talk about what it’s actually about. Homestuck is a self-aware work which is knowingly preoccupied with low or “junk” culture and this is expressed in a variety of ways. To start with an obvious one, John, the first character we are introduced to, and arguably the “shoujo heroine” of the series, lives in a room decorated with “bad movie” posters. His greatest irrational (?) fear is that the evil Betty Crocker will do something unspeakably awful to him, but Gushers replenish his health. Meanwhile, Dave, his smart-cynical rival and best friend, the ultimate “cool kid” of many talents (although he rarely leaves his room), lives surrounded by bad videogames and junk food, which he claims to love “ironically.” He is also the author of an intentionally bad dada-ist webcomic.

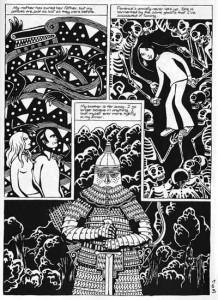

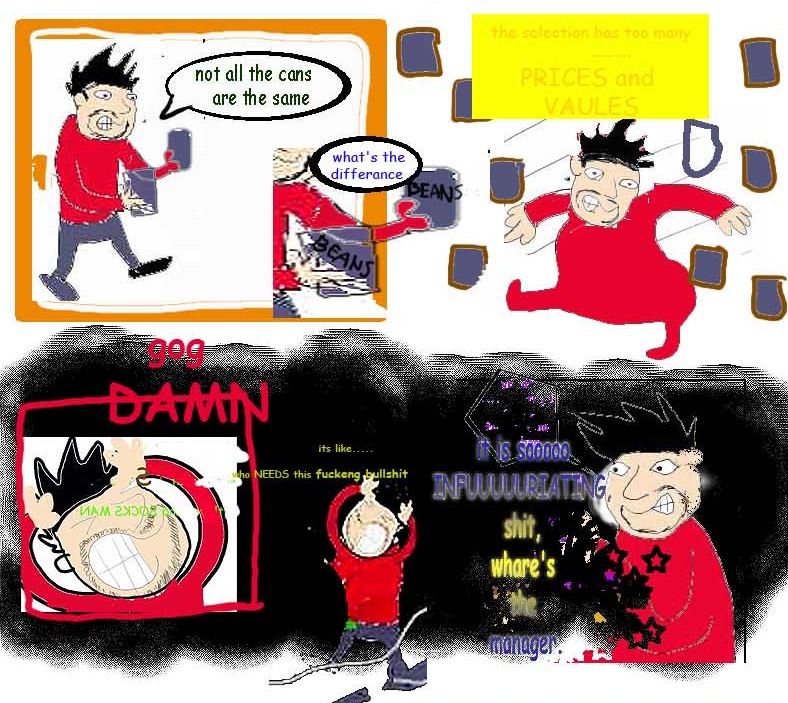

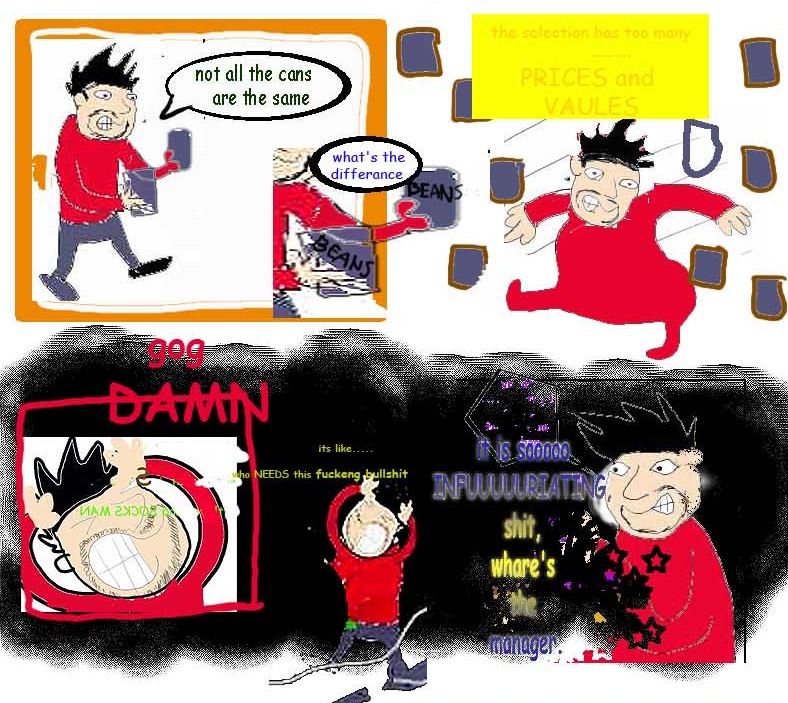

A panel from Sweet Bro and Hella Jeff,

the intentionally bad webcomic drawn “ironically” by a character in Homestuck.

The love-hate affair with low culture doesn’t end there. Whole character arcs in Homestuck are built out of bad puns, as when a character identified with the Sagittarius zodiac sign is revealed to be too strong for his own good (because he is a StrongBow – get it?). The character, “Equius,” was raised by a monster resembling a centaur who is also a butler – which is only appropriate, as his blood is literally blue.

Equius Zahaak, a character whose entire personality is built from a pun

on “blue-blooded” and the Sagittarius Zodiac sign

As frivolous and inconsequential as these jokes might have been in the hands of another author, in Homestuck they are taken, not just “seriously” as elements of the narrative which must be as carefully and exhaustively thought out as any other element of the narrative, but often to their most tragic logical endpoints. For example, the strong blue-blooded character is unable to pursue hobbies in archery or robotics as he continually breaks the equipment. More tragically, several millennia of suffering and oppression have resulted from the blood caste color system he supports.

An unrelated scene of mass death

In fact, the logic of Homestuck often dictates that frivolous things lead logically, predictably, and inevitably to tragic outcomes. For instance, when John receives a stuffed bunny from the Nicholas Cage movie Con Air for his birthday, this sets off a chain of events which causes the game he and his friends are playing to become, according to its own rules, unwinnable.

Nicholas Cage and Con Air are reoccurring jokes in Homestuck

In this way, throwaway jokes, bad movies, fast food, and other ephermalia of US and internet culture take on mythic – and often tragic – weight. It’s only appropriate, then, that the structure of the comic follows the same general shape as the Dark Carnival mythology created by horrorcore band Insane Clown Posse, becoming much darker around the 5th Arc. Like Robertson Davies, who built an entire mythology out of a kids’ snowball fight in a rural town in Canada, Andrew Hussie of Homestuck takes these elements of low culture, destined to be thrown away, and enshrines them in a traditional epic narrative.

Mass consumer culture is not the only source mined by Homestuck for hilarious or tragic potential. Internet memes – e.g. horse_ebooks, “all the things” – are also fodder for Homestuck‘s long-running epic narrative. In this way, Dave’s love/hate relationship with low culture might (if one was so inclined) be read as representative of the author’s conflicted perspective, and the work as a whole can be read as commentary on the centrality of junk to the current US cultural landscape.

Naturally, there’s another kind of “low” culture that’s central to a work as meta-referential as Homestuck: of course I’m talking about online fan culture, and specifically online fanfiction, fanart, and fanshipping culture. In the original set of characters, John and Dave hobby-program and insult each others’ tastes in music, movies, and videogames; Rose dresses in a gothic way, fights with knitting needles, and writes fanfiction about wizards. Another female character, Jade, rounds out the original set of characters and is a more-or-less wholesome person who happens to really like anthropomorphic cartoon animals (in other words, she’s a furry).

Jade, the anthropomorphic cartoon animals fan

The inclusion of recognizable fandom “types” within the comic goes a long way toward explaining Homestuck’s fan culture, which is going strong not just in traditional nerd spaces like 4chan, gameFAQs and reddit, but also in places were female media fans hang out out like tumblr, livejournal, and devientart (and of course on the Homestuck forums). Furthermore, fan activity is not a one-way street, as art & music created by fans, fan speculation, fandom romantic pairings, and fandom injokes have increasingly found their way back into the comic in a kind of inclusive and transformative echo chamber.

A character in Homestuck cosplaying as another character in Homestuck

Perhaps this is the logical endpoint of a form of comic production that originally took reader suggestions directly into account: in Andrew Hussie’s previous comics and in Homestuck before the readership reached several million, readers could write in “commands” in order to directly affect the action. On the surface, the comic is a parody – or homage? or example? – of an interactive text adventure game, maybe the ultimate form of improv storytelling in the computer age. I’m not too familiar with the genre conventions of interactive text adventure games (though like everyone else I started but never finished Hugo’s House of Horrors in middle school), so I’ll just link to Get Boat as an example of an awesome long-running work of interactive fiction of the type Homestuck aimed to be.

To enter the Homestuck fandom, then, is to be trapped in a hall of mirrors in which your own culture is reflected back at you in an immediate way by a prolific author (Andrew Hussie updates Homestuck at a rate of up to 20 panels a day). Maybe it’s this element of reflection that explains Homestuck‘s position at (from a specific point of view) the zeitgeist. The massive popularity of the comic contributes to the centrality of its messages in certain online spaces: as happened with the Joss Whedon series Firefly, phrases which originated with or were popularized by Homestuck have found their way into the everyday speech of fans: all the feels, because reasons, coolkid, grimdark.

On another level, it’s possible that Homestuck has had an impact on, not just fannish vocabulary, but also readers’ vocabulary for the discussion of mental illness. Particularly as the comic becomes darker, entire chatlogs focus around feelings of helplessness and depression. A popular fan-created spinoff series, Brainbent, combines a DSM-IV understanding of the characters with responses to individual readers about managing mental illness.

A campfire singalong from Brainbent, a fan-created spin off comic set in a mental institution

But let’s not overstate this too much: this is still a comic where comedy or tragedy is bound to interrupt any time the discussion gets too deep. Or as a friend of mine observed: “the part that’s filtered back out of this giant epic narrative made of pasted together lulzy memes is… more memes. XD;”

So what kind of comic is it that can hold all of these things – the low culture, the fan shout outs, the sudden tragic reversals which often follow times when everything seems to have been going just a bit too well?

At its core, Homestuck is a comic about creation and destruction. The reality-altering computer game the characters are playing revolves around building – building up another player’s physical space and building up your own stats – but with greater power comes greater ability to break stuff, and that’s without counting all the meteors and falling rocks and ticking time bombs and insane homicidal maniacs who now and again will randomly – except that nothing is random in a comic which revolves around prophecies (of doom), time travel (proving you are already doomed), alternate universes (which are doomed) – destroy all the stuff you just built with your awesome godlike powers. At which point, the cycle repeats…

Driven forward by the propulsive logic of this pacing style, and held within a strongly logical structure built out of playing cards, chess pieces, light/dark dualities, and time travel paradoxes (with callbacks often occurring to events hundreds of pages in the past: no one can be more obsessed with Homestuck than Andrew Hussie, who does this for a living) – the comic is a carnival of amazing things and small moments – to make up for its violent and depressing tendencies? In the world of Homestuck, there is always something new to see and experience. Animation, short videos, a soundtrack, and playable “levels” are incorporated directly into the narrative, giving Homestuck the feel of one of those trans-media megatexts discussed earlier.

Click through to watch an early atmospheric and non-spoilery animation from Homestuck

Questions to ask about the work include: is it ultimately an optimistic or a pessimistic narrative? Does the depressive logic of the series, in which characters are repeatedly told that the story will end badly no matter what they do, cancel out its huge create energy? On a personal level, outside the privilege of being able to participate, however indirectly, in a zeitgeist, is it worth your time to spend hundreds of hours on a comic which is (however knowingly and intelligently) obsessed with junk culture and might end horribly?

Of course this will devolve to questions of personal taste. Are you someone who spends a lot of time online? Do you like things that are well made with a strong understanding of cinematic framing and pace? Is there value in the pleasure of small moments, or truth in the back and forth of the characters as they discuss depression? Do you enjoy art which is self-referential and actively engaged with its audience? Do you trust in the author to deliver a satisfying ending? Are you a nerd on the internet?

Personally I have a strong suspicion that whatever the case, the series will end in a logical and appropriate way. This is Andrew Hussie’s fourth comic, after all. And anyway, who doesn’t love a good rollercoaster ride?

The Homestuckkers were out in force at Comic-Con, by the way.