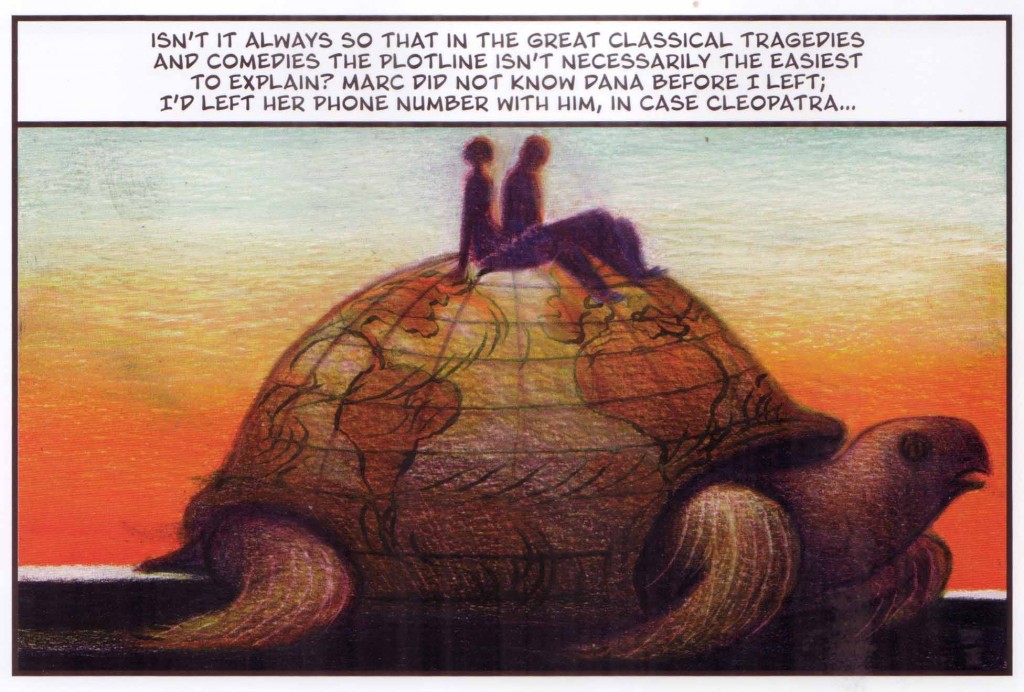

Is the question of cartooning’s status as art of interest to the world outside of cartooning? It is, enough for The New Yorker to use it as the introductory hook of a recent book review:

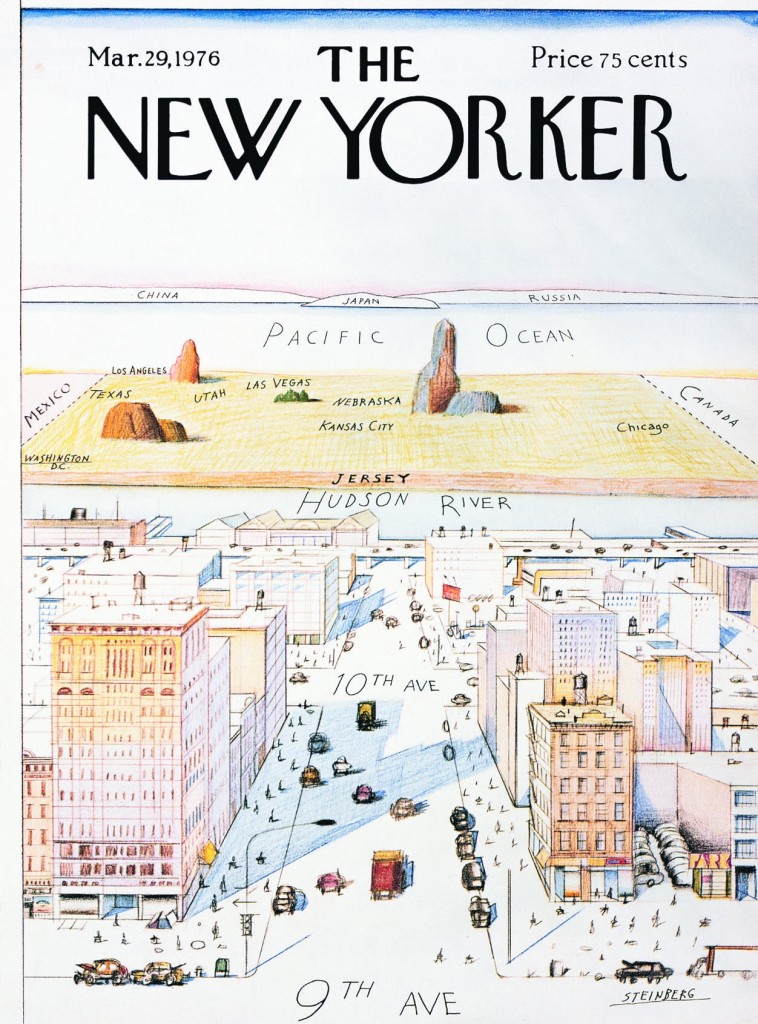

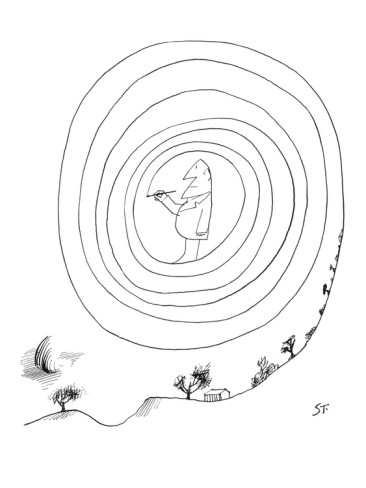

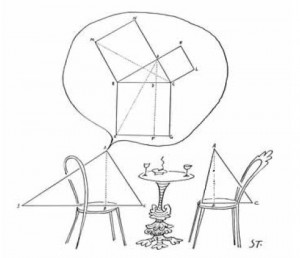

Was Saul Steinberg an artist? Deirdre Bair raises the question, which has vexed other writers, in ‘Saul Steinberg,’ (Nan A. Talese/Doubleday), a luxuriant and unsettling biography of ‘the man who did that poster’– ‘View of the World from Ninth Avenue,’ a hilariously foreshortened vista, across the Hudson River, of the United States.

Steinberg needs little introduction for many New Yorker readers, but his most famous work, and perhaps The New Yorker’s most famous cover, is mentioned for safe measure by the end of the second sentence. Peter Schjeldahl continues, “Timelessly tantalizing, “View of the World” is surely art. It is also a cartoon. Steinberg was an artist if cartooning is an art–which it is, and so he was.”

One could glibly chalk up The New Yorker as one more for the side of “cartoons as art.” More interestingly is how uneasily The New Yorker develops this proclamation, and that it made it in the first place. The statement is immediately qualified (“He was just so original and virtuosic that a different term can feel called for,”) (“Steinberg’s self-description as ‘a writer who draws,’”) and the point largely dropped in favor of a detailing of his rapscallion upbringing, scandalous relationships, depressive tendencies, and the various intellectuals he amused at dinner parties.

Schjeldahl writes

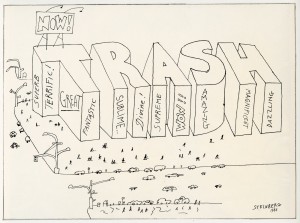

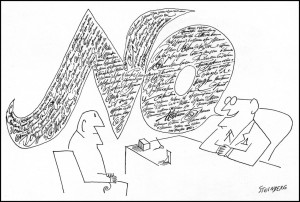

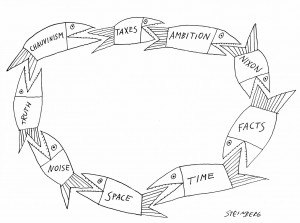

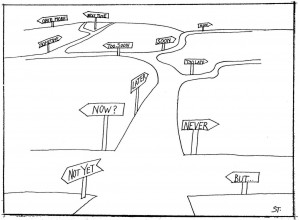

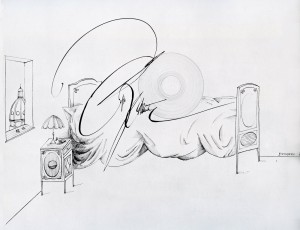

Bair makes little effort to describe Steinberg’s art. This is understandable, given the multitude and the quick-silver elusiveness of his inventions. Ideas that are impressive on paper can sound banal when paraphrased, turning back into the cliche’s that inspired him–moribund truths, often in an existentialist mode, that he would jump-start to crackling life.

That this is also a fitting description of Bair and Schjeldahl’s tack in describing Steinberg’s life, which would be great fodder for writers like Daniel Boorstin or Bart Beatty. In his book Comics Versus Art, which I reviewed here, Beatty describes the application of certain tropes, including social alienation, loneliness and a romanticization of ‘the white man as an object of societal scorn,’ to trigger an association of genius or artistry, and to masculinize a commercialized/feminized field of production. Fittingly,

Through it all, Steinberg complained of feeling loveless and alone, subject to bolting awake ‘at 3:30 full of terrors, regrets– the usual suffering,’ he said… he knew his behavior estranged him from others, but he seemed to accept the backdrafts of guilt and shame as normal weather in the impregnable mental zone from which his art flowed.

Steinberg likely constructed his self-portrayal as a tormented genius. This is more than a fascinating subject, especially when so many humbler cartoonists (and artists) are only reconstructed after-the-fact by their fans. Also, the disaffected timbre of Steinberg’s work complements, rather than complicates, this play-acting. Steinberg went so far as to say that he and Picasso were the two greatest artists of the twentieth century. An examination of how his performances as artist-commentator and socialite informed each other would have been illuminating, and it’s frustrating to see attention to the latter crowd out the former. Schjeldahl writes “I had to remind myself, trudging through Bair’s catalogue of Steinberg’s sorrows and follies, that the abounding joys of his art are the biography’s reason for being.”

Concluding the article, “He played a role that, by the luck that constitutes genius, both came to him naturally and satisfied the cravings of his time… Any old narcissist can be afflicted, and afflict others, with a conviction of being godlike. But sometimes its as if the gods agreed.” This is the extent to which the article problematizes Bair’s approach.

Bair and Schjeldahl’s words on his art are strictly laudatory, and pay tribute to the status difficulties that plague cartooning and infuriated the artist. “A starchy bias against commercial illustration persists in art circles even today, despite the fact that, in the hands of a Steinberg, it can command an immediacy and a pith that often elude the more prestigious mediums.” Yet Steinberg alone is construed as a unique victim of this bias, and the Goethe-variety of status-games ensue, beginning with his belonging “in the family of Stendhal and Joyce:”

Vladimir Nabokov called Steinberg his favorite artist. S. J. Perelman ‘always made Saul weak with laughter,’ [his wife Hedda Sterne] said. Saul Bellow was a drinking buddy. Roland Barthes was a critical champion, deeming Steinberg an ‘inexhaustable’ master of rhetorical tropes. At different times, Steinberg knew Alexander Calder, Willem de Kooning (who gave him the circa-1938 drawing “Self-Portrait with Imaginary Brother), Mark Rothko, and Philip Guston, and he revelled in the company of the grandly garrulous art critic Harold Rosenberg. A visit to Picasso in the South of France, in 1958, resulted in a collaborative “exquisite corpse” drawing… he was collegial with his fellow New Yorker cartoonists Peter Arno and, especially, Charles Addams… He found meaning for his life only in work, and maintaining his morale for it dictated his conduct. Sex, alcohol, and compulsive travel, whether on the Queen Mary to Europe or by car along the back roads of America, were reliable tonics.

The second to last sentence is contradicted not only by the entire review, but by the sentence that follows it. Finally, “he made millions of dollars.”

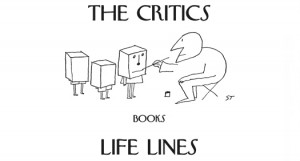

Considering that Steinberg’s cartoons are not analyzed, it would have been nice for the work itself to have been featured, even embedded in the text, as New Yorker cartoons often are. The only adorning images are a small cartoon by Steinberg, which appears above the title,

and an enormous photograph of Steinberg and his wife, Hedda Sterne, posing forcefully before an eclectically decorated fireplace.

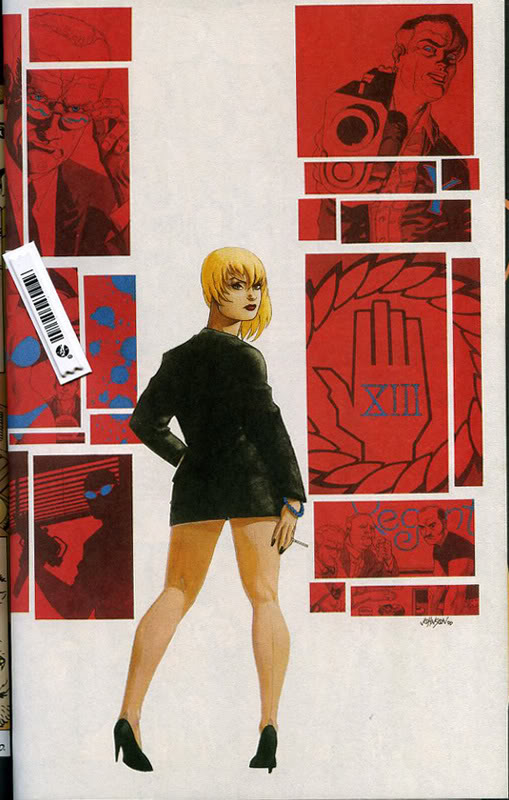

Sterne is the second in a line of four women who frame Schjeldahl’s examination of the artist. To those acquainted with the photo below, Sterne will seem familiar.

Inspiring their moniker by The Herald Tribune as ‘The Irascible Eighteen,’ this flagrantly self-promotional photo shoot collected many members of the young abstract expressionist movement in New York City, notably Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Barrett Newman. Formed in protest of a juried competition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the group was less a collective than a competitive, and the incendiary dramatics was a part of their marketing. Sterne, the only woman in the photograph, stands on a chair, presiding over the men. As an artist, Sterne never became a household name, but her presence is largely responsible for the visual interest of the photograph, and its infamy has outlived almost all of the individual’s photographed. This often-emulated photograph has haunted the New York and international art world, providing a powerful visualization of the greater myth of ‘genius society’ that accompanies most constructions of individual geniuses.

In the review, Sterne’s im-memorability is chalked up to, “her shyly independent, often changing style, and, perhaps, to the toll of the sacrificial devotion that Steinberg required of her tenure as, in her words, a ‘long-suffering, uninterruptedly betrayed wife with a few honeymoons thrown in.’” Sterne’s presences does more than link Steinberg to a hallowed fragment of New York society and art history. Sterne’s failure and merit are justified in her service to Steinberg, as Steinberg’s talent and art-world victimhood are quietly justified in his service to The New Yorker.

It’s in poor taste to focus on the glass half empty, rude to lampoon a book without reading it, and pretty obnoxious to criticize a critique. This is not a review of Bair’s book, (one is due.) Yet it is worthwhile to examine how the book is covered by The New Yorker, a publication that owes much to Steinberg. The tone of the review betrays that, in this magazine, Steinberg is already a hero. Rather than legitimately analyze his work, or penalize an account that fails to, Schjeldahl indulges in human-interest fluff and idolizing, and submits to the same biases that frustrated Steinberg during his lifetime. Steinberg obviously saw himself as exceptional, but if he really saw no true artistry in cartooning, his hunger for acceptance might have driven him out of it. Instead, he was a competitive and consistently brilliant cartoonist, with no noted artistic ambitions outside of cartooning.

Yet here, cartooning is a medium that is only transformed into art by ‘a Steinberg,’ and is deserving of the awkwardness a team captain gives his unathletic best friend when lining up for kickball. At the end of the day, a cartoonist, Steinberg ensured his immortality with his behavior as much as with his work. The New Yorker pays tribute to a generic kind of legend, which it un-conscientiously prizes above the artist who helped develop the publication. Or, it believes that it must stoop to the basest stereotypes of genius to justify reading about a cartoonist in the first place. Yet it’s puerile to believe that a proper tribute to any artist could be found in biography. A criticism of one could be expected to set things straight.