Dystopias are always also utopias, just as hell always also implies a heaven. A blighted future is a warning, but it’s also a hope that the wrong-doers (if they do not repent) will finally, finally get theirs. Orwell’s 1984 broods luxuriously on the triumph of totalitarianism over all those who do not see as clearly as he. Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games revels in the voyeuristic exploitation bloodshed enabled by scolding us all for our voyeuristic exploitation jones. Disaster porn is — adamently, enthusiastically — porn, a sadistic/masochistic wallow in the end times. Grim visions are what we want to see; the rain of fire that scourges injustice — or, sometimes, that just scourges. Because scourging is fun.

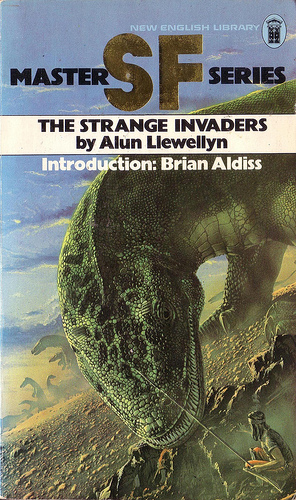

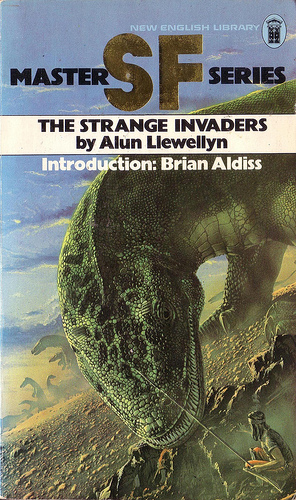

Alun Llewellyn’s 1934 sci-fi dystopia, The Strange Invaders presents a particularly complex apocalypse — and, ergo, a particularly complex set of apocalyptic desires. The story is set in a far future earth, where a combination of nuclear holocaust and oncoming ice age have knocked humanity back to the middle ages. The action is centered in a factory town of the former Soviet Union, now a holy city, inhabited by a people called the Rus. The Rus worship a Trinity — Marx, Lenin, Stalin — who they only vaguely understand. Church Fathers rule over a military class of Swords, who keep the peasants in line scraping out a subsistence existence.

This already-quite-grim-thank-you world is plunged into chaos as nomadic Tartars begin fleeing to the Rus’ holy city from the South, seeking shelter. They claim to be pursued by giant, man-eating lizards. The Church Fathers at first don’t believe it (Marx said nothing about giant man-eating lizards!) and so order the Swords and the peasants to massacre the Tartars before they eat too much of the food supply. Soon after the deed is done, though,the saurians show up and set about killing just about everyone they can get their talons on. Finally, in a War-of-the-Worldsish stroke of luck, winter comes in and for some reason the in-all-other-ways evolutionarily perfect lizards are unable to sense the temperature drop soon enough, and go dormant, allowing the few remaining humans to slaughter them. This isn’t exactly a happy ending, though; humans are now trapped between the lizards to the south and advancing glaciers to the north, and while there may be a respite for our particular band of the Rus, humanity’s long-term outlook seems awfully dicey as the book closes.

In his book Colonialism and the Emergence of Science Fiction, John Rieder reads The Strange Invaders along a number of allegorical lines. First, he notes that it maps and reverses the traditional lines of imperialism; instead of a vigorous northern European invasion of the decadent Southern periphery, Llewellyn presents a vital South launching an attack on the decadent, etiolated north.

I don’t necessarily disagree with Rieder’s take here…but I think it’s important to take into account the fact that this is not just any north we’re talking about here, but Russia in particular. Obviously, the Cold War was not underway in 1934 — but Llewellyn (according to Brian W. Aldiss’ preface) had actually visited the Soviet Union, and appears to have had a better sense of its problems than many of his contemporaries. In any case, there’s no doubt that the northern weakness here is a particularized Russian weakness. The blind obedience to authority, the inflexibility, and the cruelty of the Rus is linked specifically by Llewellyn to Communism.

It was a tale often told, a moral often preached. They had sinned; all mankind had sinned. Marx from whom the world had received the blessing of the Faith had remade the world in a plan of Five years…. The faith had been wronged and the Destruction was the vengeance enacted. Therefore must the faith be honoured strictly by those that survived, and they must to that end give obedience unquestioning, surrender thought and spirit and body to their rulers who were guardians of that faith.

Rieder of course appreciates the satirical fillip (now perhaps rendered into almost a commonplace of anti-communism) of turning the resolutely materialist Marx into a deity. But he never quite links the Russian context to the discussion of peripheries. If one does so, the novel becomes a parable not so much of reversing center and margin, but rather of wars on the margins — of Russia, perhaps, being devoured by its own atavistic, subservient Orientalist weakness.

From this perspective, then, the saurians and the Russ are not in opposition, but are on a continuum. And in fact, there is a fair bit of textual support for the idea that the giant lizards are not the death of the Rus, but their perfection. The ideal of the Rus is unthinking obedience; direction without will. Adun, the protagonist, is caught between his human desires and his society’s demand that he become merely the tool of the Fathers — a kind of machine, like those left in the factory/church and worshiped. “The Fathers and the men they kept to uphold them were not to be questioned,” Adun thinks to himself. “Mind and body they commanded, as the Faith directed. He was nothing. He dared do nothing.” (18)

If Adun has to convince himself to become an object, the giant lizards have no such problems. As Rieder notes, the creatures “hover on the uncanny border between the organic and the mechanical.” In one of the most striking passages of the novel (which Rieder quotes), the creatures are envisioned as a depersonalized collective; a single coherent unity of force.

The plain, where it came down from the river, was alive with inter-weaving movement. They played together in the sun as though its brightness made them glad, running over and under one another, swiftly and in silence, but with an almost fierce alacrity, eager and unhesitating, unceasing. The eye was not quick enough to catch the motion of their rapid, supple bodies that seemed not to move with the effort of muscles but to quiver and leap with an alert life instinct in every part of them. They were brilliant. As he looked, Karasoin saw the play of colour that ran over those great darting bodies, a changing, flashing iridescence like a jewelled mist. Their bodies were green, enamelled in scales like studs of polished jade. But as they writhed and sprang in their playing, points of bronze and gilt winked along their flanks and their throats and bellies as they leaped showed golden and orange, splashed with scarlet. Now and then one would suddenly pause and stand as if turned to a shape of gleaming metal, and then they could see plainly its long, narrow head and slender tail and the smoothly shining body borne on crouching legs that ended in hands like a man’s with long clawed fingers; five.

This is the awesome fulfillment of Ronald Reagan’s “ant heap of totalitarianism.” Stalinism is here embodied not by the proletariat, but by those even below them, the lizards forged into a remorseless, infinitely flexible machine-state. The blind watchmaker forges the revolution, and thus Marxism for Llewellyn will literally, and beautifully, eat itself.

Again, though, just because the lizards are the ultimate totalitarians doesn’t mean that the humans are somehow battling totalitarianism. In 1984, Big Brother is schematically opposed to the human emotions of love, friendship, warmth, and sex. Llewellyn’s vision is less pat. Adun’s love, not to mention his sexual desire, does in fact inspire his resistance to the regime of the Fathers. But that resistance isn’t exactly idyllic. On the contrary, Adun’s passion for the hardly-characterized Erya is almost inseparable from his own pride and desire for power. At one point he threatens (and it is not an idle threat) to kill her if she chooses the captain of the Swords, Karasoin — a murder-lust echoed by his participation in the genocidal slaughter of the Tartars within the city walls. Eventually, Adun does win Erya…by murdering Karasoin after the Sword almost rapes her. Thus, the alternative to mechanized, unfeeling destruction is not love or peace, but rather the cthonic, feeling bloodshed of jealousy, rage, and rape-revenge.

Llewellyn is willing to suggest other possibilities. Erya, for example, has a vision of independence and freedom — though that’s eventually crushed by the ongoing crisis which requires her to get a man for protection or else. Karasoin, before he actually rapes Erya, is ashamed and decides not to attack her — just in time for Adun to hack him apart. And at the book’s end, Adun’s brother Ivan speaks haltingly of the need for men to stop killing each other…and then, of course, he dies of his wounds.

The novel’s flirtations with peace, then, are all cynically inflected; they are raised to be shot down in a frisson of pathos and irony. Both the lizards and the rape-revenge narrative, on the other hand, have a visceral, awful appeal. The beautiful, terrible new force which will inherit the earth; the beautiful, terrible old force that has held the earth: they rush upon each other, soundless or howling, and from their writhing, bloody struggle there rises genre pleasures, old and new — violence, lust, apocalypse, the cleansed earth and the pleasure of watching its filthy cleansing. The Strange Invaders is a bitter reversal of imperialism, a prayer for a more perfectly genocidal imperialism, and — to the extent that its vision is enacted on and powered by Orientalist tropes — arguably an act of imperialism itself.

The final twist of the novel is, perhaps, that, despite its prescient and honorable anti-Stalinism, its apocalyptic vision is ultimately not apocalyptic enough. The saurians, in all their awesome power, and the humans, for all their ugly narrow-mindedness, can neither compare with the power, the ugliness, or the narrow-mindedness of what can’t really compare with the atrocities Stalin was perpetrating while Llewellyn was writing his book. The gigantic force of the state, wielded by a jealous, paranoid madman, was able to generate a holocaust in the Ukraine, and throughout Russia, that makes Llewellyn’s bleak vision — shot through with beauty and with joy at the bleakness — seem positively naive. That’s not Llewellyn’s fault exactly, though. History, indifferent alike to justice and desire, will always be grimmer than dystopia.

“Passers-by no longer pay attention to the corpses of starved peasants

on a street in Kharkiv, 1933.”